Gerald DiPego's Blog, page 7

January 27, 2016

The Wild

Faces lit by flames then disappearing into the night, appearing again in a great whoosh of air and fire – worried faces or full of wonder, disappearing again as I’m hurried into place. “Lie down, quickly!”

In the flashes of firelight I see a large basket tipped on its side, and this is where the people lay, two to a compartment. “Hurry, we have to leave now!” I slide into the basket, lie on my back, but my wife is shaking her head, frightened. “I can’t do it!” “You can,” says our guide, pushing her forward. She looks at me, and I’m smiling within the fiery chaos as if to say ‘what the hell are we doing?! And she smiles, too, and slides in beside me as flames reach out and silk billows and air gushes and the silk stretches and moves along the ground, dragging the basket, dragging all of us by heavy ropes as we grip the edge of the basket, and it is dragged and dragged and then begins to lift.

We feel ourselves leave the ground, but are we lying or standing now? We each rise to full height, eight passengers and a pilot, as the balloon lifts above us just as dawn bleeds into the sky. The pilot is laughing. “We got off just in time! The wind is perfect!”

When we look over the rim of the basket, we see we are gliding fifty feet above the earth. Whenever a rush of heated air is released, we hear the great whoosh, but mostly it is quiet, the earth, the sky, the dawn, and each of us passengers, stilled by the sight and the feeling that we’re in a flying dream, or we’re birds, or this is some magic.

We speed toward a hilltop and miss the grasses there by only ten feet. The dawn light is spreading, and as we top the hill we all gasp as we see them, thousands of them.

We are flying above the great migration of animals across the planes of East Africa, just fifty feet above the tens of thousands of moving or grazing wildebeests and zebras, mingled with herds of elephants, with giraffes, and every kind of sleek, darting antelope.

We take some photos, but it’s futile. We want to simply breathe it in, all of it, all of the wild life moving beneath us as we move above it. We notice that our shadow, when it glides over a group of elephants, frightens them and makes them run. The wildebeests and antelope and zebra scatter when the pilot pulls the lever and the animals hear the heated air rushing into the balloon.

It’s amazing what we can see, the thousands and the individual, the old and the young, some lumbering water buffalo now, and even the sparse, scattered trees -- to see a tree from above it, to glide over it’s top branches and see, at the very top, a nest, and in that nest, an egg, to see the multitudes and the single bits of life.

We’re above the surging thousands as they cross streams, sometimes forming long lines at the shallows, and there are predators far off, watching for the strays, the sick, old, or very young.

We pass above a kill. A lion has downed a wildebeest and is feeding on the carcass. As we approach, the lion looks up. It looks right at us. There is nothing in this great passage above the migration that will linger in my mind like the look on the face of that lion. She cares nothing for our shadow or bursts of air. She dares us. Her look, her eyes, dare us to come to her, to try to take her kill from her -– and the stare seems to range beyond this kill and this feeding. She, the lion, dares us, we humans, in our great, birdlike ship, to land, to confront her where she lives, where she hunts. There is a deep challenge in her look. I am the lion she says to me with her eyes, come and show me who you are. She is proud. Her stare is fierce. She is ready.

We sail over her, and she watches us go. We take more pictures of the endless migration. We settle in a field where they wait for us with sandwiches and a bottle of champagne for a toast.

We speak excitedly and smiles stretch our faces and we shake hands or embrace and pose together for photos, but deep inside I am saving and protecting this memory, the lion, the lion’s eyes. I saw the wild there.

January 20, 2016

Drummer in the Band

I think being a drummer is like being a redhead. You just are. At sixteen I’m the snare drummer in the Round Lake High School band, the only snare drummer. It’s a small school.

I’m head of the percussion section in the Round Lake High School concert band, pep band and marching band, and in the marching band I’m trusted to create my own street beats, those drumming solos between songs when the band is parading.

There was one long march where the crowd was in clusters along the rural highway, and I was instructed to begin a street beat whenever I saw a crowd – and that would be a signal for the band to begin our next marching tune. On this never-ending parade we past farmland, pastures, some of the band members huffing under the burden of bass drum or a Sousaphone.

We marched in silence along an empty highway. A herd of cows saw us…and came down to the fence. I started my street beat. The kids laughed. The conductor, Mr. Genualdi, gave me his wry smile, and the band played – we played The Stars and Stripes Forever to the cows, and their mild eyes followed us for a long, long while.

As a concert band we won awards, traveling to exotic cities to compete: Peoria, Rockford, Waukegan. We were good because of our conductor, who was a teacher every kid prays for, a bright, enthusiastic, compassionate man who demands your best, and so you find your best, you create it for yourself and for him, for Mr. Genualdi.

We travel to a town where the bands will compete. We reach the hotel. I share a room with a trumpet player a tuba player and the other boy in the percussion section, who plays the big bass drum. More band members begin collecting in our room, even some girls, even a boy who has somehow bought beer. Just three bottles for all of us, but we feel wild. I engineer the room, giving orders. Stand the tuba in the corner, slide the drums under the beds, put the trumpet case in the closet – give us room. The place fills up. We sit on the beds and talk with the girls. You, see, it’s 1957. So we sit on the beds and talk with the girls. Later there’s some kind of water fight. There’s more beer. A card game. Nobody sleeps. In the morning we put on our uniforms and board the bus.

We try not to sleep on the bus. We have to be sharp. We’re first on the program out of the ten competing bands, performing as soon as we arrive at the hosting school. The bus ride will last only another ten minutes. We have to have our edge, for our band, our school, our town, and for him – Mr. Genualdi in his all white uniform, sitting up front behind the bus driver.

It’s at that moment that I realize that the drums are still under the beds back in the hotel. The realization cores me like an apple. I’m hollow inside, and I’m sweating now, soaking my shirt, and yet I’m chilled. Maybe I have an instant fever. I hope I’m going to die. I keep trying to hold off the fact of the left-behind drums. It’s as if it’s a too-bright light, and I can’t look at it. Maybe if I close my eyes; maybe if I don’t think about it, or maybe if I think so hard that its not there, I can erase it.

I close my eyes, but when I open them I see the bright light. It’s the white uniform of Mr. Genualdi, who is sitting in the front of the bus, and there is nothing else to do, but to stand up and walk down the aisle and tell him.

I stand up. I begin to walk. I steady myself. The aisle seems so long. I want it to be long. I want the walk to take forever, so I never have to tell him. He sees me now, coming forward. He smiles. I try to swallow. I can’t. I have to speak. His smile is gone because he sees my expression. “I’m really sorry,” I tell him. And then I form the sentence that is like a club. He’s a mentor, he’s an inspiration, he’s a great guy, and I’m about to club him. I say the sentence. “I left the drums at the hotel.”

His eyes widen. He pales. I say again, “I’m really sorry.” Anger and disappointment crash on his face, and then he turns away. He looks out the window. He looks at his watch. His sigh is a sword entering my chest. I wish I could cut out my heart and hand it to him. When he looks at me again, he has his control. He says, “We’ll borrow some drums from a band that’s not playing till later.” And then he sighs again and shakes his head at me, but this time the small, wry, tolerant smile comes with it.

This boy standing in the aisle beside him is a good boy. This boy tries very hard. Mr. Genualdi likes this boy, and he sees this boy’s pain, and so he gives this boy absolution like a priest. Instead of the sign of the cross, it’s that wry half smile and a tolerant shake of the head. I feel relief; I feel even love; and I feel older. And we reach the school, and we play, and we win a first place for Mr. G.

January 13, 2016

Two Movie Monsters

Two Movie Monsters

(my most frightening moments in film)

“Creature From the Black Lagoon” – No

“The Wolfman” – Nope

Face-hugging Aliens from “Aliens” – scary, but…no

Dracula – Nahh

“Cujo” – Oh come on

No, the two movie monsters who scared the hell out of me, got inside me, invaded my dreams and twisted them into nightmares, gave me the tingling neck when alone in a dark place, may seem, to you, odd or even mundane, but they had power over me from ages five through twenty.

The reason they hammered me like no other monsters is a kind of mathematical equation: good acting, good direction and production + my own personal vulnerabilities = true gut-level horror.

It’s a good list of directors, by the way: David Lean, and Alfred Hitchkock. Are you starting to guess? You’re thinking, was there ever a monster in a David Lean movie?! For me there was, and she was first created by Charles Dickens and then by David Lean and then by actress Martita Hunt.

She was Miss Haversham in “Great Expectations.” Remember her? In her youth she was left standing alone at the altar, and the despair and the shock of this made her insane. When we meet her in the 1949 David Lean production she is an old woman in a decaying wedding dress. The long dinner table is still set for the wedding, but the rats have eaten the cake. She thinks the groom is still coming.

Why did she frighten me so deeply? I was eight years old in 1949. We lived in an apartment in a tough neighborhood in Chicago, and my mother, to give herself a break and to trade life for fantasy, walked my brother and I to the local movie house twice a week, every time the pictures changed, no matter what was playing. So, at only eight, the idea and the sight of a crazy old woman took my breath and made me a statue in my seat.

My brother was 12, and I didn’t think he even noticed, but the idea of a WOMAN monster, a CRAZY WOMAN, terrified me in a special way. My mother was loving and playful, and we brothers depended on her for everything because my father was usually working and we were already afraid of him, anyway. Not that he was a bad man, but there was a force in his eyes, his Italian temper, and he didn’t know how to play. It would be another decade or more before I was certain that he loved us, and it helped to see him weep at sentimental television commercials as he matured.

Was I so afraid of Miss Haversham because she showed me that a WOMAN can be crazy, and did that meant it could happen to my mother? What a spooky thought for an eight year old. I’m not sure what I thought, but that experience left me with a serious fear of crazy women on the screen, and I wasn’t the only one. Years later I told my brother and he nodded, saying “Oh, yeah. Miss Haversham. She really got me.” So it marked him, too.

Cut to 1960, and I’m a freshman in college, home for a weekend, taking my girlfriend, Joann, to a movie that was making its way around the country, causing a ripple that was felt even in little Round Lake, Illinois. We were eager to see it and chuckling over the very dramatic ad campaign. Something like: “No one will be admitted to the theater after the start of this film. Nurses will be present at many showings in case patrons faint.” The film was called “Psycho,” starring Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins.

Now we’re about 20 minutes into the movie and Janet Leigh is getting undressed. Anthony Perkins, the motel clerk, is watching her through a hole he’s made in the wall.

As Janet prepares for a shower, we hear a far away argument between the peeper, played very well by Perkins, and a woman we take to be his mother, but we don’t see her. Anthony is trying to calm the old woman who is shouting and seems dangerous.

Janet enters the shower. It’s 1960 remember, no nudity yet, only suggested, the entire sequence staged and shot to perfection by Alfred Hitchcock.

As she showers, the film suddenly explodes into a frenzy of violence so shocking it may never be equaled. It seems the old woman has rushed into the bathroom, swept the shower curtain aside and is stabbing Janet Leigh! This can’t be! Janet is the star of this film! Adding to the shock is the shrieking music, driving the scene as the knife strikes again and again and the blood begins to stream.

What we have here is my worst movie fear, the crazy old woman, like Miss Haversham, but now she has a knife! She stabs directly into my fear spot, killing the star of the movie only 20 minutes into the film!!

This old woman, to the same shrieking music, also stabs to death a detective who is mounting the stairs in her house, and by the end of this film, I am terrorized and wrecked. It’s as if I have been personally attacked. Such is the power of what (at it’s bottom) is a mere B-movie ‘slasher’, but due to genius film-making is an unforgettable shocker and a Jerry DiPego anathema.

I didn’t show Joann my fear, not wanting to seem weak. I drove her to her house and kissed her well as she kissed me, and I went to my home where my mother was absent – in the hospital for tests. I walked quietly past my parents’ bedroom where my father slept alone and turned to the staircase to my upstairs bedroom. I stopped. I could not climb those stairs – having just watched my most terrifying monster stab a detective on a similar stairway.

I was nineteen. I was so afraid. I could NOT climb those stairs. There was a monster waiting for me. I knew it wasn’t real. I was afraid of the crushing fear itself.

I walked softly into my parents’ bedroom, stared at my sleeping father, and I forced myself to speak, whispering, “Dad?” and said it once again, and he woke.

“It’s Jer,” I said. “I’m…not feeling so good. Can I sleep with you?”

He nodded, turned on his side. I took off my shoes and jeans and got into the bed beside him, nineteen, afraid, ashamed.

It was at least a year before I could take a shower without my chest tightening with ambient, illogical fear of a monster who never existed.

I’m no longer afraid of monsters, but I have never watched “Psycho” again – and I won’t. Ever.

January 6, 2016

Something About a Desert

There’s something about a desert. I mean a big desert, a get-lost-and-they-find-your-bones desert. It’s not quite emptiness because they’re not quite empty. I once drove all the way across Death Valley and saw one creature. A rabbit. It was dead.

I know that deserts are ‘alive’ because when I was a kid I saw the Disney documentary, “The Living Desert.” I remember a snake shaking its tail like a swift marimba, its song of poison and death, and I recall a tarantula fighting a huge wasp. I think it was a wasp.

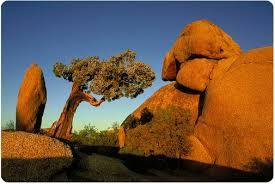

Yeah, okay, snakes, bugs, and what else? Succulents, right? And stubborn little arthritic trees, brittle weeds, armadillos – which are like small armored vehicles, which also speaks to me of danger and, again, death.

But as I aged through my sixties I began to lose all my fears, as if I dropped them along the way, as if my pocket had a hole in it and shyness fell out and was gone and self-consciousness, too, and what was left of timidity and modesty and even larger fears, public speaking, acting, and I even dropped a legitimate phobia. I can climb a tall ladder now and even let go and raise my arms above my head and unscrew the ceiling fixture in a room with high ceilings and hum a song while I’m doing it; goodbye, acrophobia.

So, feeling fearless, I decided a few years ago to make friends with the desert. I like to take a solo trip now and then, a private getaway, and this time I headed into the Mojave. It’s easy to find. Start in Southern California and drive east until the cities run out, and then the towns dwindle, and the space between everything increases, and the small inhabited places you continue to drive through are not so much towns, but desert outposts, scattered along the rim of the Great Mohave Desert.

You can’t live in these outposts without the desert getting at you. You see it all day, hear it at night, taste it’s grit, squint at its withering shine. People either don’t stay long in these outposts or they stay forever, and they make a life among the few shops and the tattoo parlors and cafés and bars. There are always bars, where people go to drink and think about…the desert.

Okay, it’s beautiful, with its spare palette, but always changing light, as the sun does its tricks near the horizon when it isn’t sledge-hammering down from above.

I chose Joshua Tree as my personal piece of the desert where I would shake hands with it and get to know it, and feel, finally, a relaxed comfort in the distinctive landscape created by Dali, maybe, and seen nowhere else in the world.

I checked in at the ranger station, then drove along one of the paved roads toward a hiking site, but was stopped along the way by the red-rock outcroppings, not jagged rocks, but big isolated piles of boulders as if ruins of some unknown kingdom. They called to me, these rounded rock piles. I wanted to walk the half mile or so (distance is hard to measure by eye in the Mohave) to one splendid castle of heaped, monolithic boulders and move among them, stand upon them and look about like a pirate on a ship, gazing at this vast sandy sea.

I knew I could keep my red Prius in sight from my destination in the rocks, and I took a camera and a sun hat and a full bottle of water. I’m no fool.

I enjoyed exploring the rocks and using their height to see my surroundings, and I saw other piles of the red monoliths, as if this area of the desert had once been a city, or a place of a hundred temples. One pile looked easily climbable up to a high perch, where I’m sure I could see the earth curving.

I walked to these boulders, settling the schematics in my head: Prius is there – first rock pile is there – second rockpile now takes me to exactly this angle from the road.

I must have spent a happy hour climbing and resting and shooting photos and drinking water, and when I was done, I climbed to a nearby shelf of rock and set my gaze toward exactly where my red car would be parked, but it wasn’t there.

This was a strange, disorienting feeling, because I had been so sure. It was one of those moments when your brain rejects the intel from your eyes. Can’t be. Is. I climbed higher and looked and…and then turned all about. Even behind my sunglasses my eyes were narrowed down because of the overpowering light.

I looked at each rock pile, trying to pick out that first one which would orient me. I wasn’t sure. I tried to crawl into my memory and FEEL the way I had come, but I still was not anywhere near certainty.

So, what could I do? No I didn’t have a cell phone, and the Mohave is short on WI FI. I had to pick the most likely direction and what? Walk, walk and keep walking until I struck the road, and what if I didn’t come upon the road after two, after three miles? The sun was still hammering, and I realized I was actually scared now, scared of the desert. I felt it had tricked me. And I wasn’t ashamed to be scared. It was logical to be afraid, but even inside the fear I still felt somewhat confident that I could choose the direction and find that road, and then find my car – or flag down a car, or…..

I started walking, aware of the irony, even smiling wryly at myself and shaking my head. He got you – this devil, this Spririt of the Desert. He tricked you, Jer. Part of this attitude was bravado I guess. I just kept walking.

It’s not easy to count miles when you walk. How many feet to a mile? And I have about a three-foot stride, so…. I just kept walking. I saw no road. I heard no cars. I just kept…..

I had a third of a bottle of water left and was tired and sore from all the climbing. It must have been about three in the afternoon. Should I stop a while in the shade of some rock or scrawny tree? Could I walk all the way back to where I started and choose another direction?

Hey, I thought. This is real. This is how a desert kills people, people who don’t really understand its power, people who screw up. I was angling toward the sun, and when I corrected and kept walking, I saw the shine of something. It could be pavement, very far away. It could be the road.

I had more energy now, but didn’t want to tire myself. As I walked, my eyes tore at that infrequent shine ahead of me, scratching for details, for certainty. After navigating a slight rise in the land and staring downward, I stopped, stopped breathing, too. There was a road.

I arrived at the road, sat on the side of the road, touched the beautiful road and smiled and waited. A car full of family stopped as I waved them down. I could see they were suspicious, some of them actually scared of me. I asked for the entrance they had used. They told me. It was only about three miles ahead. Did you pass a red car pulled off the road? They had not. So I knew my direction. It was the same direction that this family was taking, and I supposed I could have squeezed in among the children in back, but I saw their nervousness and just thanked them. They droved off, and I began, for certain this time, walking toward my car.

The red Prius was another two and a half miles down the road. I wanted to hug it. I sat inside a while, looking over the landscape, thinking again, so that’s how a desert kills you.

I imagined the Desert Spirit as a man. He wore a slight smile, just curving up slightly on one side, stared at me. Then the son of a bitch winked.

December 30, 2015

Lake Town Christmas

Part Two

(The arrival on Christmas Eve of my mother’s family, visiting from Chicago at our home in rural Round Lake, Ill, 1950s: my favorite uncles, Motts and Tony, Cousin Jim and his new wife, Carolyn, my mother’s jolly sister, Inez — these characters described in last week’s post of Part One).

They moved into our home wailing and shouting and sometimes breaking into song – the tune of Auld Lange Syne with the words “We’re here because we’re here because we’re here because we’re here,” and I can hear them still, and hear my family calling out our own greetings, and broken bits of sentences were surfacing and disappearing as if in a swift river as they came deeper into the living room clutching bags clumsy with ribboned presents, but the presents were irrelevant to me even then, because the gift was themselves and the night to come.

The food, too, was unimportant. Tomorrow would be the meal around the table. This was bread and olives and prosciutto and salami and Parmesan, and drinks were made and a gallon bottle of red wine opened and the sofa and chairs filled so that my brother and I roamed or sat on the floor, and the stories rolled out and the jokes began and the teasing and the chaotic harmony of laughter, my brother smiling but cool and quiet at first and then, and I see this so clearly, buckling as if from a blow to the stomach, bending with silent laughter, his eyes squeezed closed, and my father smiling and chuckling as if he was watching a comedy on television and my mother giggling, giggling like a girl, and then making us laugh in turn by speaking in different voices and smoking her cigarette in strange, stagey ways, and I know now that a portion of my great joy in these Christmas Eves came as I saw my own family captured and changed, our silences abandoned, our seriousness deserted.

Once the visitors came in the door, I dropped all anticipation and expectation, and there was never a plan for what we would do. It was a kind of improvised theater where any topic could catch us up and fill the room with extemporized humor on its theme. “How’s college,” Motts might ask Paul, and Paul would say, “Fine,” and Motts would look at Tony, and they would begin: “Any knowledge at that college? What have they taught you so far? Tell us something you know. Did they teach you yet about the Sanafran? No? They didn’t teach him about the Sanafran. Oh, my God. If you don’t know about the Sanafran, how’re you ever gonna learn about the Spinowizz? I don’t think I like that college. Does it have a fight song? Let’s hear it.”

And Paul would try to sing it, his stomach hurting from the suppressed laughter until his eyes watered, and soon we were all singing it, and I can hear it now. I can. I can pick out each voice, the memory making me smile at this moment, and I’m feeling tears in my throat as if this one moment in this one chosen night has been distilled into a small amount of precious liquid, and I close my eyes and listen, because now Jim, the crooner, is singing us a song from the nightclubs, and when he finishes, he’ll sing another and then begin to do impressions of the singers of the time and then sing in comic voices and made-up languages and Motts and Tony will join him while my smile shines on them like a flood light

I never knew what would happen next, and never cared, never thought ahead and never imagined that I would remember so vividly those nights and treasure those nights, and that they would sustain me through yet unimagined tragedies and lift me whenever I studied my life for meaning or sense or tried to total the pleasure against the pain.

I felt no hurry in the center of that joy. I knew there would be time, as the night ran on, for quieter moments with each of the visitors, and I knew they would listen and even care what I said, and I watched them slowly sink from the shouted hilarity into a softer mood, Motts and Inez feeling the alcohol and mourning, with my mother, the loss of a brother. There was always a somber nod toward the ghost of Frank, but then the old stories would rise and all would rise again toward the laughter, and even my father would grow small, slow eyes from the drinking, a face of his I rarely saw. He was a solid man with little to say, and he had no play to give his children, no look that lingered and examined and searched for my dreams, nothing at all that could compete with these visitors except his solidness and his steady work and the security he gave us and taught us. I knew he sometimes loaned money to my mother’s family, and I had a sense, even then, that I was somehow safer with him, in spite of his temper, but how I fed upon the play that was sometimes in my mother and that always rushed through the door with these visitors who connected with a child and reached inside of a child and somehow preserved the children within themselves.

As the level of the wine sank in the big bottle, the conversations separated and softened, and I had my time to step away with Carolyn and speak of what we’d been reading, and she would ask me if I was writing and ask to see it, and really want to see it, and I would share it with her and with no one else, not because my family would have been harsh but only because they didn’t care to go where I went with Carolyn, to the place of stories, to the mind-created worlds that presented me with wonder like a talisman to keep and to wear, and I’ve always worn it and wear it still, and in time the drinking and the clock would press our visitors down into the beds and the foldout couches, and I never remember feeling sad but only filled as those nights ended, but, of course, they haven’t ended because I can live them again and am living them again as I make these pages, and they can never be erased, even by what came after, by the changes and the losses that came swiftly at the end of those years, by Tony’s death from cancer, and by Motts finding a wife who gave him a loving steadiness and a sweet daughter and moving with them to Texas, and by Jim and Carolyn divorcing, my Carolyn moving back to Louisiana, and Jim marrying again and having a family and becoming a machinist who would not give up his dream of singing so that he sang into the noise of the machines to keep his voice strong, and, slowly, time and death took them all away from me, even Paul, all except one.

In college I wrote to Carolyn, and we connected again and I saw her when I hitchhiked to New Orleans one Easter break, and it was a deeper pleasure than I ever imagined, seeing her again, her smile entering me and finding the place I had kept for her there since I was twelve and she came for the Christmases. We wrote steadily after that and even sent tapes of our thoughts, and she married and raised two children and so did I, but all the while there was Carolyn and me and the books and the films and the wonder we shared, a relationship that lasted more than fifty years until she died only months ago, and a love that will last until I die, and when I die, there will still be one last survivor of those Christmas eves, and that will be the boy, that eager boy who waited at the window and waited to hear the train, and that train will keep wailing and keep bringing him his visitors and his dream and the pure heart of joy again and again forever.