Gerald DiPego's Blog, page 6

October 3, 2016

10 Movies that Made Me Me - Movies 1 and 2

These are films I saw between the ages of ten and twenty, films that, in some way, hit hard and went in deep and mattered, enhancing or awakening some strong feeling in the boy I was then and helping to shape the man I am now. They are in no particular order.

Movie 1 - TUNES OF GLORY, ’60(Deep inner conflict)

There is a power struggle in a Scottish regiment whose base is near a town. This is during peacetime, not long after WWII. No battles, except a battle of wills, between the popular, up-from-the-ranks acting colonel who leads with a swagger and is one-of-the-men, and a full colonel who comes to take over, a more upper class man, not a martinet, but much more strict.

Does this seem predictable? It’s not. First, there’s the brilliant casting. The tough and swaggering acting-colonel is played by Alec Guiness in a real change-over, even for this great chameleon actor. The new full colonel is played masterfully by John Mills: Two of Britain’s finest actors squaring off, and, even for a young man of nineteen, I was made aware of what the quality of performance was all about (as well as crisp writing and direction).

These two men came vividly alive to me as I dropped down into the center of their struggle. My allegiances to the characters shifted, my emotions were mixed and battling each other. The Guiness character had spent the war in combat in the desert, rising from a ranker. The Mills character had been captured and interred in Japanese prison camp. There are no flashbacks to this. We learn it. We glean it. And we watch the two men as they struggle, and there, in the theater, at nineteen, I’m jerked away from the usual hero-villain story, and find myself face to face with complex and confounding human drama and human truth, shocked in the third act and wrenched by the long, slow, ending scene.

I was wrung out by this film experience, and I treasured it, and I still do. I’ve watched the movie half a dozen times over the years and will see it again – a drama without a hero, a story as unpredictable as life. Directed by Ronald Neame, staring Guiness, Mills and Susannah York. Written by James Kennaway from his novel. An early lesson for me in the richness of quality drama.

Movie 2 - BLACKBOARD JUNGLE, ‘55

(Facing the fears)

The film startles immediately because of the music: “Rock Around the Clock,” arguably the birth of Rock and Roll to my generation and so powerful in its newness, and its rebellious abandon. An urban high school – the students arriving, the teachers, the new kids, the ‘good’ kids, the ‘mean’ kids and me, one of them, because at 14 I was just entering high school, and I was shy, nervous, afraid of not fitting in, afraid of the shaming of bullies, so that here, on the theater screen, I was pulled into a gripping drama that was one hell of a training film.

The film looked raw and real with the usual muscular direction from Richard Brooks, and it came at us during the wave of the JD craze. Juvenile Delinquency was made more frightening to America than the atom bomb, and out of the deluge of that genre arose classics like The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause and Blackboard Jungle, whose trailer used the phrases ‘Teenage Terror in the Schools!’ and ‘Teenage Savages!’

But the ‘bad kids’ weren’t monsters – that would have weakened its punch. And Glen Ford, the new teacher, a married war vet, wasn’t pure and untested – he was just a good man, hoping to do his best. The head bully among the students, Vic Morrow, had a relaxed danger about him, embodying the kind of pleasure-in-your-pain that was a 14 year-old’s nightmare. His stooge was played by a boy who went on to be a fine director, Paul Mazursky, and there was one, strong, independent student played by Sidney Poitier, who knew the streets but also seemed to have a brain and a heart.

I felt the tension as if I myself was walking into Glen Ford’s first class. I was studying for my future, nervous as hell, and looking for tips. I watched as one teacher, Richard Kiley, paid dearly for trying to become the students’ friend and share his record collection with his class – by the end of this scene the precious records are broken and so is Kiley. A pretty, but not overtly sexy woman teacher was also punished – just for her natural attractiveness, which got her pounced upon and terribly shaken. Other teachers were either very tough or very cynical, but Glen Ford kept trying.

I walked the halls with those kids and fell in with some of the humor and took on the pain and panic of the tougher moments, and I began to see…a shifting among the members of Ford’s class. I felt it too. He was gaining trust and respect from them and from me, and Potier was becoming an ally without losing his independence or his cool.

As the power shifts away from Vic Morrow, he strikes out with more evil and mayhem, and all this comes to a head in a scene of violence in the classroom. All the students are involved, me too, watching and not breathing – and learning.

Yes, those bullies populating my mind could be defeated – and not by some chance heroism but rather by a shift in attitude by the other students, a standing up, a standing together. I went ahead into high school with some gained confidence and a road map and the knowledge that there would be people to support me and teachers who cared, and maybe a Poitier to calm me and help me find my way.

#10 Movies that Made Me Me

These are films I saw between the ages of ten and twenty, films that, in some way, hit hard and went in deep and mattered, enhancing or awakening some strong feeling in the boy I was then and helping to shape the man I am now. They are in no particular order.

Movie 1 - TUNES OF GLORY, ’60(Deep inner conflict)

There is a power struggle in a Scottish regiment whose base is near a town. This is during peacetime, not long after WWII. No battles, except a battle of wills, between the popular, up-from-the-ranks acting colonel who leads with a swagger and is one-of-the-men, and a full colonel who comes to take over, a more upper class man, not a martinet, but much more strict.

Does this seem predictable? It’s not. First, there’s the brilliant casting. The tough and swaggering acting-colonel is played by Alec Guiness in a real change-over, even for this great chameleon actor. The new full colonel is played masterfully by John Mills: Two of Britain’s finest actors squaring off, and, even for a young man of nineteen, I was made aware of what the quality of performance was all about (as well as crisp writing and direction).

These two men came vividly alive to me as I dropped down into the center of their struggle. My allegiances to the characters shifted, my emotions were mixed and battling each other. The Guiness character had spent the war in combat in the desert, rising from a ranker. The Mills character had been captured and interred in Japanese prison camp. There are no flashbacks to this. We learn it. We glean it. And we watch the two men as they struggle, and there, in the theater, at nineteen, I’m jerked away from the usual hero-villain story, and find myself face to face with complex and confounding human drama and human truth, shocked in the third act and wrenched by the long, slow, ending scene.

I was wrung out by this film experience, and I treasured it, and I still do. I’ve watched the movie half a dozen times over the years and will see it again – a drama without a hero, a story as unpredictable as life. Directed by Ronald Neame, staring Guiness, Mills and Susannah York. Written by James Kennaway from his novel. An early lesson for me in the richness of quality drama.

Movie 2 - BLACKBOARD JUNGLE, ‘55

(Facing the fears)

The film startles immediately because of the music: “Rock Around the Clock,” arguably the birth of Rock and Roll to my generation and so powerful in its newness, and its rebellious abandon. An urban high school – the students arriving, the teachers, the new kids, the ‘good’ kids, the ‘mean’ kids and me, one of them, because at 14 I was just entering high school, and I was shy, nervous, afraid of not fitting in, afraid of the shaming of bullies, so that here, on the theater screen, I was pulled into a gripping drama that was one hell of a training film.

The film looked raw and real with the usual muscular direction from Richard Brooks, and it came at us during the wave of the JD craze. Juvenile Delinquency was made more frightening to America than the atom bomb, and out of the deluge of that genre arose classics like The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause and Blackboard Jungle, whose trailer used the phrases ‘Teenage Terror in the Schools!’ and ‘Teenage Savages!’

But the ‘bad kids’ weren’t monsters – that would have weakened its punch. And Glen Ford, the new teacher, a married war vet, wasn’t pure and untested – he was just a good man, hoping to do his best. The head bully among the students, Vic Morrow, had a relaxed danger about him, embodying the kind of pleasure-in-your-pain that was a 14 year-old’s nightmare. His stooge was played by a boy who went on to be a fine director, Paul Mazursky, and there was one, strong, independent student played by Sidney Poitier, who knew the streets but also seemed to have a brain and a heart.

I felt the tension as if I myself was walking into Glen Ford’s first class. I was studying for my future, nervous as hell, and looking for tips. I watched as one teacher, Richard Kiley, paid dearly for trying to become the students’ friend and share his record collection with his class – by the end of this scene the precious records are broken and so is Kiley. A pretty, but not overtly sexy woman teacher was also punished – just for her natural attractiveness, which got her pounced upon and terribly shaken. Other teachers were either very tough or very cynical, but Glen Ford kept trying.

I walked the halls with those kids and fell in with some of the humor and took on the pain and panic of the tougher moments, and I began to see…a shifting among the members of Ford’s class. I felt it too. He was gaining trust and respect from them and from me, and Potier was becoming an ally without losing his independence or his cool.

As the power shifts away from Vic Morrow, he strikes out with more evil and mayhem, and all this comes to a head in a scene of violence in the classroom. All the students are involved, me too, watching and not breathing – and learning.

Yes, those bullies populating my mind could be defeated – and not by some chance heroism but rather by a shift in attitude by the other students, a standing up, a standing together. I went ahead into high school with some gained confidence and a road map and the knowledge that there would be people to support me and teachers who cared, and maybe a Poitier to calm me and help me find my way.

#September 8, 2016

How Embarrasing!

I’m walking down a street in Dekalb, Illinois, a college boy, nineteen or twenty, coming toward me is a girl, only a slight acquaintance, maybe we have a class together, but it’s someone I’m interested in, attracted to, and look at her, she sees me and smiles, a big one. She even waves, and the smile and the wave shine a warm light. Surprised and joyous, I smile and wave, too, but as we come closer, I see that her eyes are aimed just over my shoulder, at a boy behind me. I drop my waving hand quickly and my heart drops with it, all the way to the sidewalk, as I’m blushing hotly and walking on, feeling so…

The dictionary defines embarrassment with another word: ‘abashed,' which “presupposes some initial self-confidence that receives a sudden check, producing shyness, shame or a feeling of inferiority.” Or all three packed into one second that lingers as a crisp snapshot in my memory even at age 75.

That mistaken-identity moment is a common one, isn’t it? You know the feeling.

Here I’m about twelve at a restaurant with my mother, father and brother. The waiter is recommending the special to my dad. This is only a notch above a diner. We couldn’t afford fancy and mostly ate at home. My father is nodding at the waiter and now speaking, reaching for jolly phrase, but Dad is an Italian immigrant, and his English is pretty good but not perfect. What he wants to say is “Okay, you twisted my arm.” What he says is: “Okay, you pulled my leg.” I blush and look at the tablecloth, sinking, shrinking. Another snapshot for the embarrassment album.

I believe these feelings come in their sharpest form between the ages of ten and twenty-five or so. As we age, thankfully, the blade doesn’t sink so deep. Now, when I think of the restaurant, I smile, feeling only love and warmth for my Dad, but my twelve-year-old self, in the snapshot, is abashed.

These were the years when trying on a pair of pants in a store as my mother waited outside of the cubicle, I’d be tugging at that curtain to make sure no one could see. What if someone came in?! And when in the bathroom at home (why was there no lock on that door?) if I heard someone touch the door handle, I’d shout “Somebody’s in here!” Somebody? We were a small family so I’m sure they knew who it was, but that’s what I said. And I bet you can imagine, on my first date, a high-school freshman dance, how I suffered terribly through the pain of having my father drive the car! Pick up the girl at her home! Take us to the dance! ‘Cause we were only fifteen.

Ooh, this one still chills me. My kind older brother, Paul, popular with the girls at twenty, not nearly as shy as I was (at sixteen) tells me that the girl he is dating has a sister my age, so why don’t I come with him to the girl’s home and the four of us will listen to records and dance. This is a first and a surprising blessing, so I force myself through my fears and say yes.

This memory is not a snapshot, but a video. We’re at the home of the girls. The younger sister is very pretty and not at all shy. We’re slow dancing, and I’m desperately trying for some cool and tearing through my brain like a thief, looking for witty things to say. I think I’m doing all right, but as we dance, I glance into a mirror and see that the girl I’m dancing with is giving a look to her older sister and rolling her eyes and shaking her head. No one knows I see this. Devastation.

I had failed myself and failed my brother. I don’t run this old video very often.

Here’s a lighter one. I’m the assistant janitor at an apartment building, a summer job during college. I’m outside, walking around the building, and I step on a grate – and the grate gives way, and I fall into the hole, suddenly standing in there up to my armpits! So embarrassing – except – there’s no one around. No one is on the lawn or on the street. Nobody sees me! Embarrassment disappears, and I stand in my hole and laugh.

Occasionally, I still feel some twinges of embarrassment, but they’re paper cuts compared to the arrows that struck my chest in those earlier years. Aging is freeing. I embrace it.

September 7, 2016

BookMarketingBuzzBlog Interview Text & Link

Here's the text of a brief Q&A about Write! Find the Truth in Your Fiction posted to BookMarketingBuzzBlog on June 7:

WRITE! Find the Truth in Your Fiction

1. What inspired you to write your book? One of my sons suggested it, and I looked back on all my years of professional creative writing and began to feel that I should communicate what I know, and that my method of emotion realism might help a lot of fiction writers.

2. What is it about? It’s about the art of storytelling, about capturing a reader or a film audience and taking them on a journey of our imagination, an emotional and satisfying journey that FEELS true and offers both entertainment and enrichment.

3. What do you hope will be the everlasting thoughts for readers who finish your book? I hope they’ll be thinking: I feel now that I know how to write a story (screenplay, novel, stage play) that contains that precious human truth which keeps readers caring and believing right up to the end.

4. What advice do you have for writers? Write your very best work, and get it out into the world any way you can, and while you’re waiting for the world to respond - start your next one. Persistence and belief in yourself are mandatory.

5. Where do you think the book publishing industry is heading? Like film-making, book publishing is coming closer and closer to the hands of the artist. The old school publishers and the film studios have distribution, but the artists have the Internet. Let’s see what happens.

6. What challenges did you have in writing your book? It’s not easy to step back and study and articulate your way of working - which has become instinctive after 45 years. I had to take my writing method apart and study the pieces.

7. If people can only buy one book this month, why should it be yours? Because everyone knows someone who wants to be a writer or IS a writer and needs guidance, and this book is personal, conversational, a how-to that I wish I could have read when I was beginning.

April 6, 2016

Sometimes They Let You Drive the Locomotive

I’ve been writing books and movies professionally since 1972, and most people don’t think about the research side of this work, but digging into the world of each script or novel can take a writer anywhere, everywhere, and I appreciate each journey I’ve made toward the authenticity, the human truth of what I’m writing.

Sometimes this exploration is exciting, eye-opening, heart rending, joyous, meaningful – and each piece of work I’ve done has benefitted from my seeing and touching the world of my story.

During the seventies and eighties, I was writing those network movies-of-the-week that are all gone from TV now, but I was lucky to be there when the business was so hungry for so much writing. Sometimes I wrote up to three of them a year, and each one led me somewhere, searching out some world for my study.

My journalism training and newspaper work helped me in this scouting for the reality of each world, and each journey broadened my life.

‘Runaway’ was a script about a train losing its brakes as it roared down the mountains, and I knew I’d have to write some key scenes that took place in the locomotive with its two-man crew, so the network called ahead and set up my visit to an LA train yard. The engineers were very cooperative. People generally enjoyed talking about what they do and showing me how it all worked. Before I left, the man in charge asked, “Wanna drive her?” Well, hell, yeah, and I did – just a couple of hundred feet, but it gave me a thrill along with a hands-on feeling.

Later I eagerly accepted an assignment to adapt a book called “I Heard the Owl Call My Name,” an award-winning Canadian novel about the native tribes living on the islands north of Vancouver and an Anglican Minister assigned to their church and school.

I was flown by seaplane to visit these tribal villages, sharing the sky with eagles, my first sight of them and only 30 feet from my window in the plane.

I so appreciated meeting the villagers, hearing the stories, the complaints and the joys and the day to day lives – and just taking in the rhythms of their speech, the way they moved. Being there and looking into their eyes added so much more value than simply reading the book.

Sometimes the journeys led me into the darkness and pain of a particular world, such as my 24 hour stint with a Santa Monica Fire crew, at the station and out on calls. I enjoyed the camaraderie of the station house admired their soldierly professionalism at work.

One call took us to the apartment of a woman having a heart attack. She was about 50, and once the paramedics went to work, she was soon talking them, to all the team, even to me, her wide eyes moving among us as she asked, “I’m going to be okay, now, right? I’ll be okay. I’ll be all right. Won’t I?” The medics spoke to her as they prepared her for the ambulance, telling her she would be tested at the hospital, and they would know just what to do for her. “But I’m going to be all right. Right? I know I’ll be okay.”

The last I saw of her was looking through the door of an emergency room as doctors, nurses, workers swarmed around her and someone closed the door. I followed the paramedics through their paperwork and asked them questions I needed to ask. As we were leaving the hospital we enquired about the woman and found out "She didn’t make it.”

I still see her wide eyes, full of that question, that final question.

I was hired to write a script about the juvenile prison system, a ‘School for Girls’ in New Mexico, and I was handed several newspaper and magazine articles to study. I was told we were going to shoot in an actual school, and I asked if I could go there now, before I started writing, and interview the staff and some of the girls.

I had heard, of course, how prison or reform school life can turn someone toward the dark side, create a hardened criminal out of, for instance, a girl who several times had run away from an abusive home. In many cases (back in the 70s) the abuse was denied by the parents and they willingly turned over their daughter to the system by making her a ward of the court.

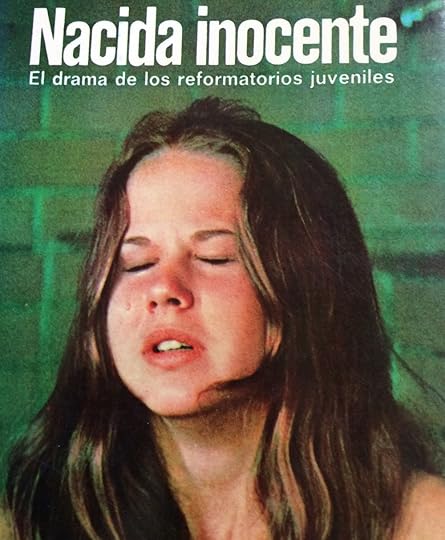

This is the story I wrote, called “Born Innocent,” starring Linda Blair, soon after her work in “The Exorcist.” From the staff and the inmates I learned about the girls who find themselves in the system and are initiated, sometimes brutally, by the worst of the inmates and made to live in fear, made to turn against their own personhood by cutting themselves, by a habit of pulling out their hair, and how they toughen and become rebellious and even dangerous.

Because I had been allowed to penetrate the veil of how these schools were thought to be and had seen and heard how they were, the film turned out truthful and gritty. Too gritty for some sponsors and some states where they refused to air it. The script was novelized and the novels were pirated in Mexico in a whole series of books called “Nacida Inocente.”

Linda Blair, Joanna Miles and Allyn Ann Mcleary delivered deep and fine performances, and the script was nominated for a WGA award – because I had been let ‘inside’ to do my research.

Film research has taken me to London, Kenya, Canada, and Washington D.C. ... but, more importantly, into the human truth of the people who live the lives we write about, and I’m better and wiser for it, and also convinced that there is a global brotherhood and sisterhood, and that the more we recognize this the closer we are to a much better world.

March 23, 2016

Abundance

This is the most rambunctious, the most lush spring season I’ve ever seen in this rural California valley where I live. My wife and I walked just two miles down our sparsely used country road, and the sights, combined with the quietude, caused us to react as if a dear friend had spread out their treasures for us to see: appreciative amazement.

In many places along the sides of the road the grasses and weeds, a healthy, vibrant green, were knee deep and untouched by anyone’s step. Swaths of wild mustard covered parts of the meadowland, and an entire volunteer army of poppies was encamped among the hills.

Horses moved slowly across their bare-ground enclaves toward their fences to see us pass, and my wife tore some handfuls of the rich grass and fed them snacks. Red-crested wood-peckers signaled from the telephone poles, and a red-tail hawk called out from the sky. A simple pleasure that left us filled as if from a feast.

Returning to my work does not mean writing, which I love as much as I love these walks and long to get back to, but it’s the challenges of self-publishing an eBook that face me now, a jungle of internet technology with my mind a dull machete, but I’m almost there. My book on creative writing, called “WRITE!” will be available soon, and I’ll let the world (as much of it as I can reach) know the date and time and procedures to acquire one.

Meanwhile, I still enjoy sharing my work with you, so I robbed the poetry drawer today and pulled out two of my ‘traveling poems’ in case you might enjoy. Be well… Jerry

I-40 Cuts

I-40 cuts across bare

bony eastern Arizona

like a scar, structures

appearing without

context in the fields or

scattered and separate

in the wind-scraped towns,

and one, in faded metal,

has stood too long, a giant

word painted along its

rusted roof where

it used to shout at

the blind, humming cars

and trucks: “GARAGE,”

but sun, rain, ice and the

iron indifference of the

passing millions have

reduced the word to only

“RAGE”

The Highway

I’m taking California’s 101 south to L.A.

and the ocean’s on my left, no, on my right

and I’m doing 74 past the site of Port Hueneme

so I touch my neck feeling for the chain

pull out a navy I.D. tag, World War II

and shake it so it jingles. Maybe somebody

sees me from the other lane, wondering why

that old man is jingling his necklace that way,

so I explain and say my dad was a sailor in ‘44

stationed at Hueneme and after that had a long

life and a grocery store, and when he died there

wasn’t much. I chose the I.D. tag and my brother

picked the watch, so when I pass this place

I picture dad in the photo in his sailor clothes

white hat, happy and bewildered face, 35

years old and his youngest son only 3, so I didn’t

know him yet, and he didn’t know me, but maybe

I was on his mind, and now he’s on mine when I

pass here and see the sign, so I jingle the tag to say

hello to the sailor he used to be and hope the sound

somehow connects him to me, because there wasn’t

Nearly enough connecting, though he lived to be 82,

and maybe there never is is what I’d say to you or

whoever saw me in the blue Prius on 101, a man of

74 waving a chain because he’s still somebody’s son.

February 24, 2016

Foreign Films Save the World!

What?! Save the world? Well, yeah. Hang on. Let me make my case. I grew up in rural Illinois in the fifties, loved reading and loved movies, and never saw a foreign film until I went to college.

I was curious, but I figured they’d be strange, esoteric. I didn’t think I could relate to the culture and wouldn’t fully understand. I didn’t know if reading subtitles would spoil the movie experience I loved so much, and I figured, like most Americans, that Hollywood was where the real professionals, the experts, the major filmmakers were, and other countries were trying to emulate us, playing catch up. What an idiot – but I think most Americans thought that then, and some still do.

It was my junior year, and I was sharing a basement and a hot plate with four other guys. It’s what I could afford. Wasn’t awful, didn’t complain, but it was so good to get out on my own at night.

I was working on the school paper and saw the story about foreign films to be shown, starting that week, every Friday night at some campus theater. All right. I’m in.

So the first film I saw was an Ingmar Bergman work, “Sawdust and Tinsel.” And it WAS strange and esoteric, and frigging hypnotizing, too. Just four or five subtitles into it, and the reading was no problem. The film was set in a circus. There was a bear. There was a ringmaster who looked like the bear. No, I didn’t get all the ideas Ingmar wanted me to, but I was pulled into his tale and holding it to my heart from the beginning: love and rage and shame and heartbreak, and in this film everybody’s heart broke, mine, too! And the bear died. Whoa. I came out of that theater as if from some shattering event – not a film, a flesh and blood event.

All right, so the Swedes knew what they were doing, from story to actor to director to cinematographer.... The film owed nothing to Hollywood and was a better, deeper drama than all but a few American films I had seen. Well, maybe that was just the genius of Bergman. Nope.

I saw fine Spanish films and Dutch and the great Italian gift of “La Strada” which broke my heart all over again. Oh? You say you have a taste for Japanese. “Woman in the Dunes” will knock you on your ass. I was emotionally punched and reeling from these films every Friday, and the final knockout came from Kurosawa and his “The Seven Samurai.”

I had seen “The Magnificent Seven,” and really enjoyed it except for a few weak spots: Buchholz and Vaughn. I loved the story, characters – and that score! I had known, when I saw it, that it was based on a Japanese film and remembered thinking that the foreign version would be more stilted and no fun. Jeez. Kurosawa’s movie was better and deeper in every respect, so much more human, the characters more real, the action more stunning, everything working together to raise the experience from entertainment to classic masterpiece, without losing anything, neither the humor nor the fierce battles for survival.

So I was converted. I gained great respect for the films from other countries, from their classics and from their new films of the sixties, where England was on the rise, and the French and Italian and Russian and Asian cinemas were all delivering as much or more than our own films – which were now competing in the breaking of molds and the exploring of new territory.

But here is what else I learned. Here is the deeper part of this message, and it’s simple. I learned that we’re all the same, all over the world. I was watching films not about the American condition or the German condition or the Chinese condition, but about the human condition. I was learning that the wish for love, peace, a job and a safe place for one’s family is common to every country. I was learning that this comical tragedy called modern life was playing out in everybody’s love stories and dramas and crime stories and action films and comedies, and it was, in essence, the same story everywhere.

The translated books and subtitled films from other countries could teach everybody who reads and sees them that there truly is one humanity, and that there are no evil countries or pure countries. If I had had any prejudiced thoughts of race or ethnicity when I stepped into those Friday night foreign films, I would have left those thoughts right there, among the spilled popcorn and candy.

I once heard a distressing statistic, years ago, that only 9% of the American movie audience ever watches foreign films.

That’s what has to change. The more people of every country who watch the films of every other country, the more this feeling grows, that they are us and we are them. And, yeah, that could save the world.

So, how do we get more Americans to watch foreign films? I was hoping you could tell me, and tell your friends, and tell everybody. We need some new ideas for spreading this blessing around, like, for instance, instead of making an American version of every hit foreign film, just release the damn foreign film – with a campaign. People went to see “The Artist,” and even read the subtitles. People who have heard how really good a new foreign film is might just step over the rope this time and take a look.

Here’s hoping.

End

(This post will remain in this position for 3 weeks instead of one, while I give my time to the launching of my Ebook, “WRITE!” – a personal, conversational how-to on creative writing. All my posts are available on this site. Thank you. Jerry)

February 17, 2016

I never want to be that scared again.

Decades ago. My first time in London, on vacation with my then wife, Pauline, and our two young sons: Justin, 8, Zachary, 4. Our last day before flying back to L.A. Pauline is in the hotel, packing, and I have the boys in London’s old (1538) and immense (350 acres) Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens.

I’m snapping photos of the ducks on the Serpentine, breathing in the history and talking to the boys, probably about Kipling, and surely about Dickens because not long ago in L.A. we had seen the musical play “Oliver!” The boys loved it.

We reach the Elfin Oak, a large hallowed-out trunk imbedded with small statues of animals, elves and fairies. Nearby is a children’s playground. Zack wants to stay at the tree. Justin chooses the playground. There is an entrance nearby. “When you come out, we’ll be right near this tree,” I tell him. He nods and runs off.

Zack and I talk about the tree, probably making up stories about the statues while Justin plays on the slide and other playground equipment.

Maybe 45 minutes later I feel a small thought squirming to the surface. Hasn’t Justin been gone a long time? I watch what I can see of the playground, and I can no longer pick him out.

“Zack, I have to walk to the left and to the right to see all the playground. I’ll keep you in sight, Okay?”

Zack nods, but I see he’s a little worried.

I hurry to search each side of the large playground, glancing often at Zack’s small form by the tree, giving him a smile so he doesn’t catch the urgency that is growing inside of me. I study every boy, every glimpse of thick brown hair. Justin is not in the playground. He’s not there.

When I come back to the tree, I’m sending my eyes everywhere, trying to push the fear down, back into the hole it came out of. He has to be nearby. I will see him in this next second, in this one, in….

“Where is he,” Zack asks with tears beginning to seep into his voice. The sound of my little boy and his frightened face cuts me inside.

“He has to be right around here,” I say, and we both look. I hate to leave the tree, our only home ground, but Justin is not in sight, and I have to widen the search.

Zack and I move to higher ground. I send my eyes thrusting into every boy’s face, every mop of hair. The fear is filling my chest like an expanding balloon. He’s gone. No. No! I’ll see him. I’ll see him now. Now.

I have to cover more ground. I bring Zack to where two wide walking lanes intersect and ask him to please stand there. “Please, Zack. I’ll keep looking back at you but I have to run around, all around. You’ll see me and I’ll see you. Here, I’ll leave my camera here, so I can run better.” I hang the camera on my little boy and it reaches down to his knees. He stands there, upset, but holding it together. I begin to run.

Now, as I run, I begin to shout Justin’s name as loud as I can, and each shout makes the fear grow and the fact more real. “Justin!” I can’t see him. I can’t find him. I keep running and glancing at Zack and running on. People are staring at me, concerned. I keep shouting, tearing my voice. I don’t see him anywhere. How far could he have gone? Gone. He’s gone.

When I come back to the intersection of lanes, my little soldier is sniffing at tears. He tells me that a big dog came up to him and scared him, but he stood there.

He stood there.

I pick him up and hold him. I can barely talk because the fear is now like a second body inside me, and it’s so heavy and so dark. I look around one more time, but I have to face it. I cannot find my son. We’re in a large park in a foreign city, and I cannot find my son.

I hold Zack and walk to the nearest street that borders the park. I see a red phone booth and hurry there, and we enter.

I put Zack down and somehow, with the English coins and the unfamiliar phone system, I’m able to call the police. I tell my story quickly. They will send an officer.

Then I make the call you never want to make, the call that seems impossible, the worst call I have ever made. I call the hotel. I am switched to our room, and Pauline answers. There is a space of a second or so before I can speak when I realize how what I say will shake her to her soul, the pain and terror and wild impossibility of it.

I tell her that our son is missing, and she takes it in. I know it cores her, but she takes it in, asks questions, wants to come to the park. I ask her to stay in the room, by the phone, in case he’s found by somebody, in case he remembers the name of the hotel. Please. Please.

Zack and I wait for the officer, and he comes in a few minutes, driving a small size police car. He’s a tall man in shirt-sleeves and the Bobby helmet. He’s relaxed as he gets out of the car. He’s smiling a bit. He’s older than I am – and he’s certain.

“We’ll find the little one,” he says, and I feed on his smile, on his voice, on his certainty. I stuff it all into me.

The car is made small so it can drive on the walking lanes of the giant park. He drives slowly, Zack and I staring everywhere, everywhere, for minutes, for more minutes. More.

I see, ahead of us, far ahead, a woman walking our way, a child is holding her hand. It’s him. It’s him. It’s my Justin. It’s him.

An ecstasy of gratefulness replaces the fear. Zack and I hurry to meet him.

He ran out of the playground and didn’t see us, he says, so he started to search. He is sniffling a little, but is fine. My son. Fine. Here. In my arms. I’m a statue, holding him, eyes closed now, holding him and holding Zack.

Later, in the hotel, his mother asks him what he was going to do.

“I didn’t remember the hotel,” he says, and I knew you were leaving in the morning, so…”

“You actually thought we’d go home without you,” Pauline says, laughing, eyes still full.

Justin shrugs and takes some things out of his pocket that he found in the park when he was alone, a sharp stone, a coin…? “I thought I’d just be…”

“Be what?”

“Like a London street boy. Like in ‘Oliver’

February 10, 2016

Witnessing

In 2014 I went on a trip called “Witness and Remembrance” with the Road Scholar organization, studying the Holocaust in Berlin and in Auschwitz, the camp/museum. I write here only of the touring of Berlin, and some of the surprises I found there.

These are called ‘The Stumbling Stones.” They are small brass plaques found here and there in the neighborhoods of Berlin. They are only about three inches square, so in order to reach what is written on them, one has to bend very low – or kneel down.

One of them reads: “Here lived Jacob Bergoffen.” He was a Jew, and this was his home. It tells us that he was born in 1892, deported to Auschwitz and murdered there on the 31st of August, 1942. Next to his Plaque is one for Felli Berghoffen, her dates, her deportation and murder in Auschwitz. Here was a couple who lived in a house on a street at this site and mingled with non-Jewish neighbors, perhaps worked with them. They were Germans of Jewish Faith, and the assimilation story of the Jews into German life, up to 1933, was a success story. There was always a vein of anti-semitism, but not until the Nazi regime came to power and began its ‘Race War’ did that vein begin to bleed.

When Jews were deported to the camps, non-Jews moved in and took over their homes, and often all their property was sold at auction, the money going to the State, the Nazi Regime. All traces of the Berghoffans and so many others were wiped out as if they had never existed. Not anymore. Now there are the Stumbling Stones, about 5,000 so far just in Berlin.

Jews and non-Jews did the research on the murdered and raised neighborhood initiatives to mark the spot where they had lived. Jews and non-Jews keep the plaques clean, shine them. In order to shine a Stumbling Stone, one has to bend very low – or, as I said, kneel down. In this way the Berghoffens are remembered, honored and not erased.

This is typical of the movements toward understanding, full disclosure, and the honoring of all the victims of those twelve years, 1933-1945, when Germany was driven by racial hatred and true “Race War" as the Nazi’s called it. In 1939, before the war began, in a speech by Hitler, he promised “the historic annihilation of race enemies.” Annihilation. What a word.

Now memorials exist throughout Berlin, for the murdered Jews, the Gypsies, the homosexuals, the very elderly, the sick and the mentally ill and the deformed – all murdered by the Nazis. In breeding the myth of a strong “Aryan Race” the Nazis believed these elements were poisonous.

Now people come to these memorials from everywhere in the world, and some leaves stones and flowers – just to mark that someone stopped here, some one took note, someone cared.

Even the train tracks are now marked, where the journey from Berlin to the camps began, as a reminder. Every train that left the city carrying people to the camps is remembered here, when it left, how many Jews were carried, and where the train was bound, and here, too, people come to leave tokens as a remembrance, an honoring, a witnessing that those murdered millions were not erased, not forgotten and will never be forgotten.

February 3, 2016

Latin Jazz?

“What do you think of Latin Jazz?”

I throw him that question as a rope because he’s off balance and about to fall into his delusion, telling me again how he was driven down a dark road and someone in the back seat put the barrel of a gun against his head. “I swear I heard that hammer cocked.” He has said this three times, and I ask him again, "Who would do that to you?” “Greyhound Bus drivers,” he tells me.

This was one day after his ex-wife had called from Illinois, saying he had borrowed money from one of his ‘bar friends’ and was on his way to California to see me. I’m his friend since the fourth grade, through high school and college and first marriages. He had decided to visit me instead of our usual two letters and one call a year, and he had been ejected from a Greyhound Bus in one of the tossed off towns at the southeastern end of the L.A. sprawl.

“The driver said I was drunk and was disturbing the passengers,” he told me when he called, “but the driver lied.” He had to put the phone down and ask for the name of the town and the motel. I called the motel office for directions. In an hour I was knocking at his door, and he was opening it and stepping back. He’s my age and we have the same name. Jerry. We were sixty-two then, but he looked seventy that day. More. He was smoking and shaking. He told me his Greyhound story. I took him out for something to eat.

Jerry was a bassist in jazz groups that played in clubs around Chicago, played for weddings and parties. He was also a bartender and a skilled repairer of reed instruments, and he was a loyal lover of alcohol, like his mother, who had died of it, and his sister, who had also died of it, and his father, who had almost died, but sobered and survived.

After eating, Jerry is calmer, and we go back to his motel room so he can pack his things and come home with me to Santa Monica. He’ll stay with me for a few days, dry out, make a plan. I’ll buy him a plane ticket, give him some cash and wish him luck. Why not? For years he was the only one who knew me, all of me, from fourth grade through one year of college, through all those years of shyness that made us nearly mute, when we were observing the world like scouts, studying and reporting back to each other what we had seen and heard and felt, and wondering if we could ever understand that world and belong to it.

In the motel room he admits that some of his Greyhound story is blurring in his memory, and I suggest that he might have had a panic attack. He says maybe, but I see that he’s holding on to that ride through the night and the cocking of the gun and is about to tell it all over again, so I say, picking up on a conversation we had in the restaurant, “What do you think of Latin jazz,” and I don’t do this just to deflect him. I’m offering him a place to stand and a venue for expressing what he knows, what he owns.

He goes through a moment of cigarette management, lighting it and inhaling and fingering it out of his mouth and blowing the smoke as he squints, and this gives him back some of his style and his cool, and he shakes his head and says, “I don’t like it. Too much percussion.” And for a minute, he’s another Jerry, more solid and well.

He went back to Chicago and didn’t follow his plan. He never wrote or called me. He gave me no phone number where he could be reached. He was my old friend, and I helped him, but how much? I was afraid. I admit that. I was afraid of the drink. I was afraid of the con. Later, I heard from his ex-wife that he had lost his instrument repair job, and he had lost his apartment, too. She thought he might be living in his car, and then there was nothing more.

He could still be out there, though, somewhere, surviving. I think of him that way. I picture him somehow reading this. Jer, are you reading this? Are you out there? If you are, listen to me, and please tell me something, will you? Tell me this. What do you think of Dave Brubeck as compared to Oscar Peterson?