Gerald DiPego's Blog, page 5

January 5, 2017

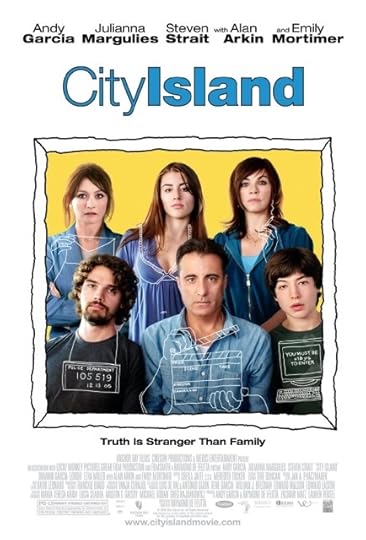

Movies We Watch Again ... and Again - City Island

Why do we watch a movie more than once? Maybe we were so stunned by the film that, by watching it again, we can study it more deeply and gain more understanding of its riches, (for me, Birdman is a recent example). Then, we might decide to see that same film yet again, because now our eyes can visit every part of the screen, pick up every background nuance, squeeze out every drop of meaning.

Other films we see may not stun us or challenge us, but seep into our emotions and go so deep that we well-up or even weep, either with sorrow, or with a deep joy, and these films we re-watch not for the studying but…. Well, it’s like visiting a dear friend for the comfort you know you will receive, and you want to feel that again.

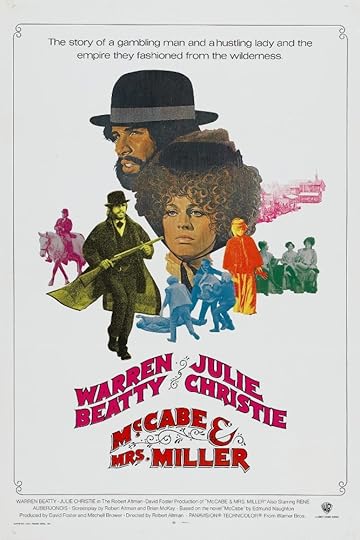

Before I begin the third movie in this series, I want to include these comments on last week’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

From John Hill: I used to say McCabe and Mrs. Miller was the High Noon of the new generation of filmmakers. Plot is basically the same, ending the same – except and especially, the anti-hero dies. And Mrs. Miller hardly wore white, like Grace Kelly did.

From J Kahn: I always loved McCabe. I’ve seen it several times myself. Wonderfully moody, inevitably tragic, unlike any other Western I know.

City Island - 2009

I’m pulled back into this film every few years because it’s damn funny, but, interestingly, it’s not a farce. A Fish Called Wanda is one of my top picks for comedy, and so is the classic Bringing Up Baby, but those present themselves as farce – broadly satirical comedy and improbable plot. City Island, however, asks us to believe that this Rizzo family exists in the City Island area of New York, so the story needs to offer us situations that feel as if they could possibly happen in the real world, AND also offer us characters that are well-drawn and deep enough so that we care about them.

The writer-director, Raymond De Felitta, is a very smart and funny man. He creates a family whose members love each other and also are often at odds. There is usually some yelling at the table. And … there are secrets. Each one: Father (Andy Garcia), Mother (Julianna Margulies), a college-age daughter, and a teenage son all have something that they don’t want the others to know. Andy Garcia, for instance, who is a blue collar prison guard, dreams of being an actor, like his hero, Brando, but he’s not comfortable sharing this dream, and so when he takes his acting class, one evening a week, he says to his family that he’s at a poker game.

The acting teacher is played by Alan Arkin, who, staying in the bounds of reality, makes this character very smart and funny, and Arkin even gets a chance to rave against ‘method acting.’ Sublime. Later watch Andy Garcia playing his blue-collar character at an audition for a film. Priceless. Even though this is a comedy, these are some of the very best roles for Garcia and Arkin and Margulies.

So now we have Andy Garcia, father, prison guard and secret acting student, come up against ANOTHER secret, and it rocks him. He has not told his wife that in his youth he sired a son. He could not tolerate the son’s mother (a psycho bitch!) so he gave her what money he had – and she took off and gave him no access to his son. Garcia, at work one day, notices a new prisoner, in his early twenties, who carries his ex-wife’s last name. The young man is big and tough and also … nice. Garcia looks up this prisoner’s background, and it IS his son.

Garcia has a building project going on at his house, which he is trying to do himself. He feels both shaken and also deeply warmed by finally seeing his other son. He tells no one, not even the young man, about his fathering of this person, but he finagles a way to bring the young prisoner home, to help him with the project.

If the acting class is considered important as a secret, this SON business is a megaton bomb. Oh the tangled web: Andy’s wife suspects that he is NOT playing poker but is having an affair. Andy’s daughter is keeping the secret that she has been kicked out of college. So in order to earn some money so she can enter another school, she is secretly working as a dancer in a strip club. I don’t need to tell you any more of the secrets, just that they abound, and that the writer/director weaves this all together so that it is both heartfelt and wildly funny.

My wife and I return to this film every few years because it is such a hearty and complete meal -- even when you know the plot and know when the laughs are coming. Maybe it’s like walking into a house that you lived in and enjoyed years ago, and you want to step inside again and find the memories and emotions waiting for you in every room. That’s one reason we watch certain movies again ... and again.

December 23, 2016

Movies We Watch Again ... and Again - "McCabe and Mrs. Miller"

Why do we watch a movie more than once? Maybe we were so stunned by the film that, by watching it again, we can study it more deeply and gain more understanding of its riches. (For me, “Birdman” is a recent example.) Then, we might decide to see that same film yet again, because now our eyes can visit every part of the screen, pick up every background nuance, squeeze out every drop of meaning…

Other films we see may not stun us or challenge us, but seep into our emotions and go so deep that we well up or even weep, either with sorrow, or with a deep joy, and these films we re-watch not for the studying but… Well, it’s like visiting a dear friend for the comfort you know you will receive, and you want to feel that again.

For my second example of a film rewatched, I give you this post by a good friend and producer, Curtis Burch.

In the summer of 1971, I saw Robert Altman’s classic western “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” the day it opened. I was 16. I didn’t get it. I couldn’t see its images clearly and couldn’t hear the dialogue.

Pauline Kael’s rave review in The New Yorker motivated me to see it a second time a week later. Maybe I’d missed something. I had. The second time was like putting on a pair of stereographic glasses; suddenly I was being transported into the past, to a town I would, on many, many multiple viewings, come to know well. The town is Presbyterian Church, named after its most prominent structure.

For the longest time I returned to the movie over and over because I loved its mood and atmosphere made rich by D.P. Vilmos Zsgimond, production designer Leon Ericksen and songwriter Leonard Cohen. It wasn’t until later that I realized how drawn I was to the character of John McCabe (the great Warren Beatty doing his best work, though he’s always disowned the movie). McCabe is a unique figure in westerns. He’s handsome, charismatic and ambitious. He comes into town and rebuilds it to his own vision making a real success of himself as a saloon and brothel owner. But he’s not very smart and he loses his locus of power by falling in love with his newly acquired partner, the far more astute Mrs. Miller.

After a certain midpoint in the story, everything McCabe does is to try to win over the unreachable affections of the beautiful madam (the most luminous Julie Christie). The movie follows the sad, tragic decline of a decent man with poor instincts.

People have written about the movie as a metaphor for the flaws in American capitalism and it entirely works that way if you want it to. But mostly it’s just a beautiful heart-breaker. Everyone in the huge ensemble is great: Keith Carradine, Rene Auberjonois, Shelley Duvall, Bert Remsen, many, many others, including the entire crew who are building the town in the background, in costume, as the movie progresses. It was shot on a small plot of land against a hill in Vancouver, British Columbia. I visited the spot once, now fully developed with modern homes. But standing there, I could still pick up the spirit of the movie.

I continue to see it once every year or two. I went to a screening of it in Beverly Hills this past March at which Kathryn Altman, the widow, spoke eloquently about the experience of making the movie. Sadly, she died a few days later. I just recently bought the new 4K Criterion restoration on Blu-ray. I’ll never stop going to Presbyterian Church. For some reason that I still don’t entirely get, I’m irrevocably drawn to the sad descent of John McCabe.

December 10, 2016

Movies We Watch Again ... and Again

Why do we watch a movie more than once? Maybe we were so stunned by the film that, by watching it again, we can study it more deeply and gain more understanding of its riches, (for me, “Birdman” is a recent example). Then, we might decide to see that same film yet again, because now our eyes can visit every part of the screen, pick up every background nuance, squeeze out every drop of meaning...

Other films we see may not stun us or challenge us, but seep into our emotions and go so deep that we well-up or even weep, either with sorrow, or with a deep joy, and these films we re-watch not for the studying but… Well, it’s like visiting a dear friend for the comfort you know you will receive, and you want to feel that again.

There is nostalgia here, and you come back to the movie to feel again what you felt the very first time – that first watching that moved you so. You want that feeling to cover you again like an old soft quilt. (Some people watch “It’s a Wonderful Life” every Christmas!)

For my first example of a stunning film I keep rewatching, I’ve picked “Point Blank,” 1967directed by John Boorman and staring Lee Marvin.

I just put it on a half hour ago because, knowing I was writing about it, I wanted to check the sequence of the opening with what I remembered. I meant to see the first five minutes and sat there for half an hour because this film still fascinates me. I have seen it at least five times over the years.

The plot is very simple: Lee Marvin and his best friend commit a crime. They’re take is $93,000. The best friend AND Marvin’s wife betray him. His best friend shoots him, leaves him for dead, and his friend and his wife escape with the money.

We’ve seen this ‘revenge’ story more than a thousand times. But not one directed by John Boorman. I think this a masterwork, both in the direction and the performance by Lee Marvin.

From the very beginning, Boorman plays with time, intercutting past moments with the current story – but no, it’s never confusing. Never. The flashbacks are short, often without dialogue, and they grow in meaning every time they come. Imagine this: a very early scene in a long hallway, almost a tunnel. It might be the arrival hall of an airport, and Lee Marvin is walking down the hall, coming at us as the camera pulls back. All we hear are his steady footsteps, loud in this hallway and beating like a clock.

He looks good, wears a nice suit, and does not portray a man who is angry and vengeful. No, he looks purposeful, but with no particular emotion. We don’t know how he survived the betrayal and the two shots that took him down. All we know is that he is back and time has gone by and he has been given the address where his friend and his wife are living.

While he is walking down this hallway and we are listening to the metronome of his hard shoes on the hard floor, the film cuts to scenes of his wife in her home, rising, dressing, putting on make-up. But all these cuts are played with Marvin’s loud steps continuing. A great choice because as we watch her moving through what she thinks is a normal morning, we also hear this ‘clock’ ticking away. Even when we cut to her in a beauty salon getting a treatment, it is only his steps we hear.

We watch her coming home to her apartment, and when she closes the door behind her, it is suddenly kicked in by Marvin, who has a gun and who never stops moving, gathering her up with one arm, then dropping her on the floor outside of the bedroom, and, still moving, kicking in the bedroom door and advancing on the bed, looking fierce now, firing his gun into that bed – all six shots. Then, and only then, he realizes that there is no one in the bed. He looks surprised, confused a moment. As if, in his mind, he has lived this moment so many times…it takes him a few seconds to change realities.

It’s as if he IS a man in a tunnel, a tunnel in his mind. His wife, now a drugged and depressed woman, tells him that his best friend doesn’t live with her anymore. Marvin, still holding his gun, sits on the couch and so does she. He doesn’t look at her, deep in his mind, in his thoughts, in his tunnel. She says that she can’t sleep, that she’s been dreaming of him. He still doesn’t look at her. She watches him and says, “How good it must feel, being dead. Is it?”

This is said to him again in the film by another character, and, of course, we wonder. Is this man some kind of ghost? It isn’t that he doesn’t function normally. He can smile and con his way past people – in order to go further down his tunnel, toward his betraying friend, and toward the next man and the next, in order to get the money he feels he is owed – that $93,000, as if he’s missing a piece of himself, something that was taken out of him when he was betrayed and shot. It’s not about money at all, not about what he can buy. Maybe that missing piece of him is his past, his heart.

I present my personal awards for the directing, editing and best actor for this film. And I feel…… Oh, excuse me.

I’m sorry. I have to go now. I want to watch it again.

November 29, 2016

Movies That Made Us Us - Continued

Some of you responded to this ‘formative movies’ subject with your own titles, everything from Gidget to The Manchurian Candidate, and many more, and I thank you. Three of my fellow screenwriters sent their own essays, and so here I share their thoughts and memories with you. Last week was the first. In this column are the second and third. I have taken liberties and condensed their writings a bit, but you’ll get the picture. (pun)

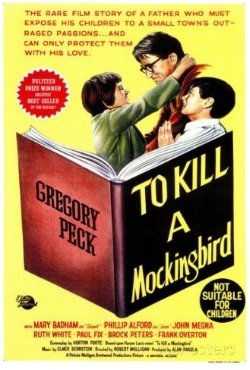

Charlie Peters: To Kill a Mockingbird 1962

The movie that affected me most was To Kill a Mockingbird. I was ten years old and the year before I saw it for the first time I’d watched my own father die. Naturally, a bit lost and dark (Saturnine, one of my teachers in England called me) Atticus Finch became for me, as he did for many other kids, a father figure. He also had my father’s mid-west tone: handsome, cool, reserved and in charge as most men of that time were.

When I was 30, the director of the film, Robert Mulligan, was directing a not very successful comedy of mine with Sally Field and James Caan called Kiss Me Goodbye. But I got a chance to talk to Mulligan about directing Mockingbird. The script by Horton Foote is, in my opinion, the best screenplay ever written. There is not a single unnecessary word or scene.

Atticus Finch is still a hero of mine. No movie moved me like Mockingbird. There are four scenes that I cry over when I simply remember them. The shooting of the rabid dog and the pride of Atticus’s son. And when in the balcony of the courtroom the black minister says, “Stand up, children, your father is passing.” And even the breakfast scene when Scout mocks her poor little neighbor for smothering his pancakes in syrup, and Atticus chides her for that. It’s a moment that many children have: Scout knows it’s an important moment and that someday she will understand why it moved her. But not then. As I got older I remembered many things my elders said to me because I somehow knew I should remember them. I didn’t know what they meant when I was a boy, but I did when I was older.

John Hill: Red River 1948

The most formative movie in my life was probably Red River (next was Shane). At age 10 or 12 I only knew that these were "cool movies" that somehow meant something to me. Now at my advanced stage of life, I understand the psychological underpinnings of why these movies were metaphors that spoke to me at a deeper level.

In Red River, I saw a totally take-charge, in control figure in John Wayne’s character, (mirroring my macho military father in real life – he quit college to go to England and fly Spitfires in the Battle of Britain.) Wayne’s foster son, Matt, is played by Montgomery Clift, and he’s the one I related to as a boy and teen.

They start an unheard of, first time ever, cattle drive from Texas to Kansas through all the Indians, rustlers, weather, etc. Under the stress and desperation of the drive, the John Wayne character starts being way too obnoxious and wrong – and the son stands up to him! Clift takes over, leaving the vengeful John Wayne behind him who is vowing death and revenge, soon, and we believe him. So the son figure (me in my imagination) takes the cattle successfully to Abilene. The son is a hero, but they all know that John Wayne is coming after them to kill Clift.

Near the end Wayne comes on shooting, but the son won’t draw on him, so an epic public fist-fight ensues! Once the son hits him back, that’s when Walter Brennan, as lifetime friend of the Wayne character, knows that “everything will be all right.” The fight is broken up by the Joann Dru character, shooting near them, and screaming “Stop it! Stop it! Anyone with half a brain knows you both love each other!”

The two men look sheepish, and then Wayne says, “Matt, I think you better marry that girl.” And, in a friendly way, Clift says back “When are you going to stop telling people what to do?” John Wayne’s answer is to draw a new cattle brand there in the dust, his own Red River D, but now adding Matt’s initial, saying “You earned it.”

Meaning, I was wrong and you, son, were right, and now you’re a man.

The movie spoke to me deeply for this reason (movies are often our fantasies made real). How I stood up to my father and what happened is the stuff for too many drinks some night, not here, but I know that is what so warmed me to Red River.

November 16, 2016

Movies That Made Us Us

Some of you responded to this ‘formative movies’ subject with your own titles, everything from Gidget to The Manchurian Candidate, and many more, and I thank you. Three of my fellow screenwriters sent their own essays, and so here I share their thoughts and memories with you. This is the first, and the others will follow over the next two weeks. I have taken liberties and condensed their writings a bit, but you’ll get the picture. (pun)

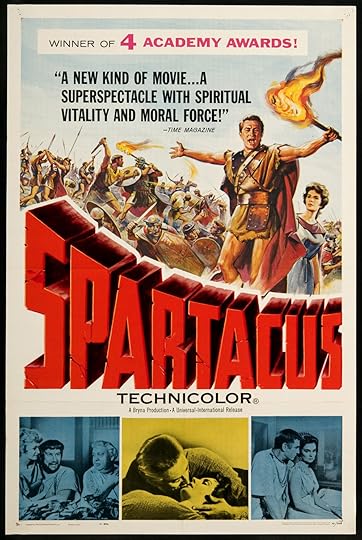

J. Kahn: SPARTACUS 1960

First, I was 12 when I saw Spartacus for the first time, starting high school, intensely interested in girls but too shy to act, not very good at sports, feeling like a weakling. Second, the country itself was going through an equally drastic identity crisis with the growing Civil Rights movement. And finally, I was the only Jew in a high school of 2000 gentiles.

SPARTACUS concerns a slave rebellion against the Roman Empire, led by Spartacus, a gladiator. The slave army marches toward the sea in order to sail to a land where they can be free, fighting and winning battles against Roman battalions along the way to the coast.

Like teenagers everywhere, I felt enslaved, more so for being Jewish, and feeling like I had to hide or risk humiliation or violence. So, in my heart, I was Spartacus.

There was this electric, sensual, but ultimately tender scene in which Spartacus is offered a slave woman to have sex with as a prize for having won a gladiatorial bout – an unimaginable temptation to my hormonally exploding self – and he declines because he respects her humanity, because of his recognition that if it was wrong for him to be a slave, it was wrong for her, too. And for me too! Me too!

The ships taking the escaped slave army away from the Roman Empire betray Spartacus and leave his army stranded. The rebel slaves turn to face the giant Roman army that means to crush them. The odds are impossible. The slaves are doomed. But they decide to fight anyway. Many are killed but many hundreds are captured.

Then the Big Cheese of the Roman army trots his horse over to the defeated remnants of the slave army, and he makes them an offer. He knows Spartacus is still alive among them, and has become a cult figure, and this general doesn’t want his mystery to haunt the Empire, or inspire future rebellions. So he says if Spartacus identifies himself, he’ll be killed, but all the rebel slaves will be spared and allowed to go back to their masters unharmed. If they don’t turn over their leader, all of them will be crucified.

Spartacus rises and starts to identify himself – I think he even says, I’m Sp…. But the slave rebel beside him stands up and says “I am Spartacus! This makes me weepy even just to write this sentence now. I mean it. Soon dozens of slave warriors, and then hundreds, men and women, captured from every country, are all standing up shouting, “I am Spartacus!”

And there’s this incredible sad, proud close-up of Kirk Douglas as he registers that all these people he’s tried to carry to freedom, like Moses, are now sacrificing themselves to crucifixion in order to save him, and to say they are all one, they’re equally the body and soul of this rebellion, what happens to one, happens to all. Their shouts, and their faces – that’s the Moment.

This resonated with me on so many levels… Spartacus said I wasn’t alone, and because of that I could be brave in making the right moral decisions. He said lots of us are slaves, but if we hang together, we can overcome slavery and history, even if the Roman army crucifies us. I think this was critical to my becoming, to my joining the Civil Rights movement, and the anti-war movement, and commitments to fighting various social injustices over the course of my life.

November 2, 2016

10 Movies That Made Me Me - Movies 9 and 10

These are films I saw between the ages of ten and twenty, films that, in some way, hit hard and went in deep and mattered, enhancing or awakening some strong feeling in the boy I was then and helping to shape the man I am now. They are in no particular order.

Movie 9 - STAGECOACH, '39(a hero)

I watched this film again and again on early TV until I knew every scene and almost every word, and even carried the musical theme in my mind (and still do). It had everything: thrills, the mystical Apache Indians, interesting characters who were very well played, romance, and a hero.

The film follows an ancient path of storytelling: a mix of distinctive characters on a dangerous journey, each of them revealed in depth by the turns of the tale. In this case they are traveling on a stagecoach through Apache country in the 1880s.

One of the passengers is a man who has escaped custody in order to hunt down the dangerous Plummer boys who murdered his brother, and this young man’s name is Ringo, and he is played by another young man, John Wayne.

I had never seen Wayne’s earlier work in B westerns. This was my introduction, and I unabashedly admit that when Wayne played his first scene, when he stands in the desert and fires his rifle to halt the stagecoach, and then twirls that Winchester, he became my hero – no, not the actor (although I was very drawn to Wayne’s early work and saw nearly all his films.) It was the character, Ringo, who rose up out of the film and captured me.

I wanted to BE Ringo. I wanted to move as he moved, in a deliberate way that also contained a kind of grace, to be what he was, a good man, a bit toughened by life, but with a sense of humor and a surprising tenderness.

He was the only passenger on the coach who treated the prostitute among them as a worthy woman, worthy of kindness and respect. It touched her to be treated that way, and it touched me, and even at eleven or twelve, I hoped that I could grow to be a man who could surprise a woman with kindness, tenderness. I could BE a Ringo. I just needed to grow and find more confidence, and then I could navigate the world as Ringo did, taking his time, never nervous or awkward and always ready for a laugh or a fight -- but only a worthy fight, a good against evil fight.

The Apaches attack the coach, and seeing the fluidity of Ringo in action riveted me, and I wondered and hoped that maybe I could learn that, that knowing efficiency of motion, that courage under pressure. I could learn to do that, if I kept Ringo as my model and carried him with me through the labyrinth of SCHOOL.

I could walk down the crowded, booming hallways more slowly, more contained. My shyness would lessen, and, when it came to bullies, I could be ready, not tight and worried, but steady and calm and ready for anything.

The stagecoach is rescued and the passengers arrive in town, and as night settles, Ringo has to face his toughest challenge, those mean-hearted, murdering Plummer boys.

Ringo was not fearless. I could see that he knew he might die, but he was steady, and he was teaching me. Jerry – be steady and face trouble, whatever it is. Yes, even that impossibly tall ladder in my father’s grocery store, changing the sale signs by reaching nearly to the high ceiling to pull them down and then raise the new ones, my knees shaking, stomach tight, signaling DANGER, DANGER! So, next time I would try to be Ringo on that ladder, slow and deliberate, maybe scared, but steady.

There were three Plummer boys (impossible odds!) walking straight for Ringo on that dark street. When would they shoot? When would they shoot?!

The fight began, and after his first shot, Ringo throws himself down on the ground to make less of a target and keeps cocking and firing his rifle because he KNOWS what to do and does it in that deliberate and fluid motion. He KNOWS, like someday I would know and not hesitate or flinch or wonder, but KNOW.

He triumphs and thinks now he has to go back into custody, but the sheriff surprises him, says he’s free, lets him have a buckboard and his new girl-who-loves-him, and they go off to the ‘little ranch’ he told her about, and I thought, maybe someday I’ll have a little ranch and a loving girl and I’ll make that happen partly because of a touchstone I’ve have carried around called Ringo.

Movie 10 - ON THE WATERFRONT, '54(a new hero)

This memory is more clear and accessible than any other time, from ages 10 to 20, when a movie ended and I rose from my seat and shuffled to the aisle and made my way out of the theater, and I saw hundreds of movies then, but this moment will be with me forever. I was thirteen or fourteen (our little theater in Round Lake, Illinois did not get first run features.) and that boy who was me, the boy who stood up to leave that theater, was not the same boy who had come in and taken his seat.

During the showing, I was shaken by powerful forces, and one was the performance by Brando. This was new. Somehow he had carved his character, Terry Malloy, out of his own flesh. It was beyond the acting I was used to. It was so much more real, even, somehow, dangerously real, an electric shock of authenticity on the screen.

Another powerful force was the filmmaking itself, the reality of those grey, urban locations, the streets and alleys I had known in my early years in Chicago. This film felt more true to life than any film I had seen, as if it wasn’t appearing on the theater’s screen at all. Instead, the screen was a large window into an actual place where these people were playing out their lives. It was expertly cast-in-depth and expertly directed by Elia Kazan, and the music, by Leonard Bernstein, never seemed to play over the film, but to come from within it. I can still hear that mournful trumpet.

And the story penetrated because of this reality. I was totally engulfed and swept along by the writing of Bud Schulberg, which disappeared as writing and came out as stark realism, as I saw through that great window into the drama and danger in the lives of these people.

Here was a new and different hero for me. Terry Malloy, a man of my time, of the here and now, and I was caught up in the anguish he feels for having been part of the murder of a neighborhood man he knew (he thought that the gangsters who controlled the docks were only going to rough him up – instead they throw the man off a roof, and Malloy is stunned, his loyalties torn already in this early scene of the film.) He works on the docks and does what the gangsters tell him to do, and in this neighborhood of the waterfront, you don’t rat, you don’t go to the cops.

So Malloy caries this anguish through the film, as he begins to fall in love (with the dead man’s sister!) as he opens his eyes to the thugs to whom he has given his allegiance (his own brother is in with the criminals) and I am sitting there feeling not only for him but with him, and that is the final power of this movie. I lived inside of it, inside of Malloy, a tortured man with a troubled past, and a new awakening inside of him that is moving him toward a terrible and dangerous choice.

Doing good, in so many movies I saw at that time, came down to the hero defeating the villain, often in a gun fight or fist fight. This film is much more complex. Doing something good, in this story, could get Terry Malloy killed, and everything about his upbringing pushes him toward staying quiet, going along, keeping your head down. This conflict makes him tear open his own life, his past in order to make this critical decision, staying safe or going after the evil on those docks, not with a gun or a fight, but flinging the truth at it.

This was a new hero for me. In the movie “Stagecoach” I had linked myself with the Ringo character, and, as the movie ended, I wanted to BE him. In “On The Waterfront,” as the movie ended, I sat there a while, feeling the great weight of this drama, and when I stood and slowly made my way out of the theater, I didn’t want to be Terry Malloy. I wanted to be a better man.

Even at fourteen, I wanted my life to have purpose. Even if it was a struggle, like Malloy’s struggle, I wanted to give something. I wanted to do the right thing.

October 23, 2016

10 Movies That Made Me Me - Movies 7 and 8

These are films I saw between the ages of ten and twenty, films that, in some way, hit hard and went in deep and mattered, enhancing or awakening some strong feeling in the boy I was then and helping to shape the man I am now. They are in no particular order.

Movie 7 - THE FOUR FEATHERS, '39(redemption)

This Brit film played again and again on early TV, as if it was made for the boy that I was in the 1940s (born in 41) and early 50s. My favorite book then was “Kipling’s Stories for Boys,” and I read and reread his tales of India and the clashes there between the colonizing Brits and native peoples who rejected British Rule. I loved the illustrations, uniforms, scenes of conflict and sense of history, and I collected toy soldiers to match that period and carried out great battles on the floor, whispering the shots, outcries and bugle calls.

This is a film of epic size, directed by Alexander Korda, with battle scenes that thrilled me again and again, but it was the story and the journey of the main character that made this movie so meaningful.

Boys playing war do begin to think – what if that was me? What would I do? Would I be heroic? Would I be terrified? I received a good lesson from this film and its lead character, Harry Faversham. His father is a respected general, and he sits at a formal table as a teen and listens to retired officers talking about their battle experiences. He is shy and reticent, and his father is a stern bully, and Harry knows very early that he will be sucked into a military life. How he will perform and how will he be judged by his father and his ancestors, whose portraits line the wall of his father’s great house.

That’s the intro – now we see Harry as a young officer in a peacetime regiment in England, gathering his young officer friends at a party at his father’s home to celebrate Harry’s engagement to his love. During this party, telegrams are delivered. War has broken out in the Sudan, and his regiment is being called up to join the war against the Mahdi’s tribesmen. Only Harry receives the telegrams – for himself and his three fellow officers, and, in a moment alone, a moment of fear, he tosses the telegrams into a fireplace. He has planned to leave the army, and this ‘delay’ that he is causing will give him time to become a civilian and marry his girl and never face battle.

Well, he is seen ‘burning something’ that night, and when questions are raised, he admits what he has done. Before going off to war, his three officer friends each present him with a white feather of cowardice. He is hit very hard by this, but then shattered when his fiancé breaks the engagement and gives him a white feather of her own.

So, as a boy watching this film, I had now lived through Harry’s conflict and cowardice, and I was shattered, too. I watched him as a broken young man who is tempted by suicide. I stared fear and shame in the face.

But Harry rouses himself and makes a very bold plan. He travels to the Sudan as a civilian and there he learns how to disguise himself as a cast-off Sudanese, darkening his skin, wearing ragged clothes and becoming what appears to be a brain-addled mute, who can travel without much notice all the way to the battlefront. His plan is to watch over his officer friends and find a way somehow to help each of them in the conflict, to protect them, to win back their respect and cause them to take back their feathers of cowardice.

So, as a boy, I have now been plunged into a heavy situation of fear and shame that rattles me, and, in the rest of the film, I take this journey with Harry, which has become my journey, toward redemption. Harry’s bravery is not the trumpeting kind. He suffers, stays hidden, follows, waits for his chances, risks his life and comes very close to sacrificing his own. So when redemption is reached, both Harry and I have changed, deepened, aged, and I’ve lived through the shame that most boys fear, and then seen that one can come back from this, can survive and redeem oneself – an important journey for me in this old film that I watched six or seven times at least – for its thrills and its lessons.

Let’s jump forward to the 1970s in LA where I’ve begun a career as a screenwriter for television films. A producer, Norman Rosemont, is making quality films from classic stories, which open as features in the U.K and play on American TV (such as “The Count of Monte Cristo”). My agent calls and says that Rosemont is offering me the writing job for his next film, and he asks me, “Have you ever heard of a book called ‘The Four Feathers?’

So, yes, it actually happened, and I wrote my version of this classic story that I had carried deep inside myself all those years. What a business. What a life. Beau Bridges and Jane Seymore starred, and the well-made film was directed by Donald Sharp. By now there were at least four remakes of this story. I began my own particular opening scene with Harry, as a young boy, playing on the floor of the mansion with his lead soldiers – blending Harry and Jerry forever.

Movie 8 - THE TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE, ’48(brotherhood)

This is also a film I saw on early television, and watched more than once, not only because of the excitement and adventure, but because the characters reached inside of me, living there as real people, and I watched them stumble along, facing strong odds, trying to make decisions that would get them what they wanted -- the treasure that was inside that mountain, but at what cost?

Humphrey Bogart and Tim Holt play busted men in Tampico, Mexico in the 30’s – rigging oil camps when they can get the work and cheated out of their money and fighting the crooked boss to get it back – and then wondering what’s next, what job? What chance? And where’s the hope?

In a rat-trap flop house they meet a very lively and talkative old knock-around played by Walter Huston (academy award for this). He’s been around, been wealthy and busted more than once, and he’s both funny and philosophical. He talks about gold – not just as money, but as a kind of fever, says he’s chased it around the world and, old as he is, he’d go again if he had the money for the equipment.

Bogart and Holt think hard about this – and then pool their money with what the old man has left, and by god, they do it. Huston knows just what to buy, and they outfit themselves with burros, tools, food and all they need to create a prospecting camp.

They go into the wild Sierra Madre – the tougher to get to the better, says Huston – where no one else has been.

As their journey begins, a theme is introduced by composer, Max Steiner. It’s a ‘going-along’ melody, a ‘song’ of this little group, played lightly as a ditty, as they wind upward into the Mother Mountain.

When the old man sees the first signs of gold in the rocks and dirt he laughs like crazy and even dances a jig – and then they get to the labor of tearing that precious metal out of the mountain.

They work hard, finding a cave to make into a small mine, shoring it up and going at the veins of gold in the rocks with picks. They’re already doing well, gathering the raw gold like sand, weighing it each night, already thousands of dollars ahead, and here comes the moment, the moment in this film that went so deep and stayed with me all these years.

Holt is carrying a load out of the mine and Bogart is still in there slamming away at the walls – and that’s when the cave-in comes. The beams that shore up the dig crack. Bogart cries out. Holt turns and sees a billowing of dust pour out of the cave as it’s mouth is covered by rocks and broken beams. He hurries to the entrance and stares in through the rubble. He can’t even see where Bogart is lying hurt – or dead. He stares in shock, and then…the look deepens into something else as a thought overtakes him. It’s a deep and weighty look, a wondering look, and you know, you KNOW what he’s thinking – if only two of them are left, each gets a larger share of the gold.

He starts to move away from the cave in – and then stops – and struggles – and then, with great determination, moves toward that rubble and starts to move it away with all his strength, digging with his bare hands toward his friend. At this moment that musical theme comes back, but it’s played strongly and building, that song of the three of them and the ragged brotherhood they have formed. It’s a moment that has never left me and never will. Without a word it celebrated the triumph of brotherhood over greed, and it builds to a kind of symphony as Holt pulls the unconscious Bogart out of the collapsed mine.

As a boy this scene filled me with great emotion, even tears, and as an old man, the tears come even more freely.

Greed and gold-fever haunt this film, and I won’t go into how the story goes so you can see it as new if you’ve never seen it, and, if that’s the case, I envy you and the first-time emotional twists and punches that await you as each man is brought to the edge of darkness. The way the characters meet this challenge has so much to say about that scale that has gold dust on one side and love on the other.

Wonderful direction by John Huston, and if you call me, I’ll sing you that theme.

October 17, 2016

10 Movies That Made Me Me - Movies 5 and 6

These are films I saw between the ages of ten and twenty, films that, in some way, hit hard and went in deep and mattered, enhancing or awakening some strong feeling in the boy I was then and helping to shape the man I am now. They are in no particular order.

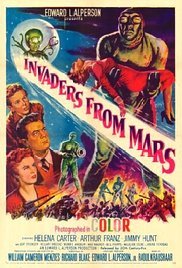

Movie 5 - INVADERS FROM MARS, '53(what if?!)

I was 12 when I saw this one, and it drove like an arrow into the most vulnerable part of myself. It was years before the wound healed and the reoccurring nightmares left for good.

Aliens were landing on the earth. You didn’t see them. They made holes in the earth, in the sand. They were hidden, but they could come out – and they didn’t kill humans and eat them, far worse. They ‘took them over’. They would plant a tiny bar of metal into the back of a person’s head, and from then on that man or woman was changed, never smiled, was never animated and had, in his or her eyes, a malignant look.

All of this hit me hard and went so deep because the film focuses on the child character, on the boy of the family, on me! This boy and I seemed to meld together as we watched the story and listened to the very creepy music and held our breath as, one-by-one, several people in this small town ‘changed’.

The boy tries to understand what’s going on. His parents are helping him, becoming caught up in the fear, until a moment comes when the frightened boy approaches his dad – and sees that the man is cold now, not the same at all. Oh my god – his father. They got his father. It was the strongest movie shock I had ever felt up to that time. The boy’s world is shaken, falling. He tries to tell his mother, and it’s this moment that is branded on my brain, when he walks into a room and his mom turns to see him, and there it is: the cold, malignant stare of his own mother.

I don’t remember one more minute of this film. I think it had a happy ending and the boy gets his loving parents back by the finish. But that came too late for me. I had already imagined seeing, in my mother’s face, a malignant stranger – and this was the reoccurring nightmare that showed up a dozen times during my boyhood. And I had a loving mother, a funny mother, and maybe that’s why the fear went so deep. What if SHE changed? What if that look came into HER eyes, the woman I depended on for care and affection and safety and love and…. What if she looked at me as if I was a hateful stranger? This particular what-if knocks the struts out from under a child’s world and goes right to the eternal core of his or her fear.

Okay, it’s a movie. It scared the hell out of me and gave me nightmares, but it didn’t scar me or crack me. I survived as most of us survive the fears that tumble along with the joys of childhood. But, wow, what an impression! I don’t believe this would have happened if I had read a novel of the exact same story. Only a film can carry this kind of punch because film is the closest medium to the human dream state. Films and dreams are like twins. They behave the same way, not anchored to any page or stage, with their juxtaposed scenes and their dialogue and the way they cut, sometimes jaggedly, from setting to setting anywhere on the earth or off the earth. I believe that it’s this closeness to human dreaming that gives film its power.

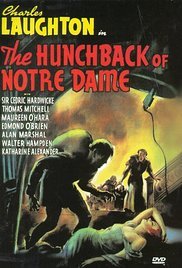

Movie 6 - THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME, ’39

(transformation)

I was about 10 when this classic was re-released in the early fifties, and in those days my friends and I didn’t pay much attention to movie starting times. We just went, whenever we could, to our one theater, a Quonset hut just outside our rural town in Illinois. If we walked in in the middle of a film, so? We watched the rest of it, then waited, caught the newsreel, the cartoon, coming attractions and then watched the repeated film until somebody said: ‘this is where we came in,’ and we left.

So I walked into this dark theater, into a raucous roar of wild shouts and laughter on the soundtrack, seeing only the screen, and this screen was full of the face of Quasimodo, the hunchback, a close-up as he’s led through the streets of Paris and crowned King of Fools. Charles Laughton played the hunchback, or rather became the hunchback, his face and body deformed, his expressions terrible, his voice inhuman, even his laughter frightening, grotesque. He was hideous, and I was stopped dead in the aisle, holding my popcorn, a frozen boy. I wanted to run back to the lobby and out of the theater, but I was with my older brother, Paul, and his friends, and I couldn’t bolt. “C’mon!” came Paul’s whispered shout as he stood at a row of empty seats, motioning to me.

I looked away from the monster and found my seat and then was pulled back into the horror, because I couldn’t keep my eyes away from this marvel of ugliness. It was too real. HE was too real. And we DID think of The Hunchback of ND as a monster within a list of ‘monster’ stories: Wolfman, Dracula, Frankenstein, etc. So, yes, I was expecting a monster film, but nothing so human or so tangible, so overpowering as this. Monster movies were dark and mysterious, with only peeks at the fierce creature now and then – but this daytime carnival on the streets of Paris was dumped right into my lap.

I didn’t know the story. I had never even read the Classic Comics version of it, let alone the wonderful novel by Victor Hugo (one of the few classics I’ve read three times over the years and will likely read again)

It had what seemed to be the trappings of a monster story – the ‘beast’s’ keeper, an archbishop, the beautiful gypsy girl who dances in the street for coins, and who is there to be threatened by the monster, right? And then rescued from him by the hero at the end, right? But wait. That wasn’t the story at all.

I saw that the monster was deaf. That he was simple. That he was shy – and then I saw him on trial and then the victim of a public whipping, and left tied to the pillory, bloody and thirsty, and I felt sorry. I felt sorry for the monster. Esmeralda, the lovely dancer, conquers her fear of him and gives him some water. It’s a great moment.

Later in the story, when Esmeralda herself is falsely accused of a crime, it is SHE who is taken to the pillory – to the gallows! She is about to be killed – but there IS a hero in this story, and the hero is Quasimodo! He pushes aside the guards, gathers up the girl and escapes with her into the Sanctuary of the Cathedral where he lives, he being the bell ringer. This monster is a hero! What a transformation. But then this change goes beyond his heroism, and we see his tenderness with the girl, and we watch him shyly show her his world of the bell tower, and show her his friends, the great bells, whom he has named and who have made him deaf with their powerful tolling.

He defends her against a mob that surrounds the church. He’s ready to give his life for her, and, of course, he falls forever and completely in love with the beautiful Esmeralda, and this is where he disappears forever as monster. At this point in the film, Quasimodo has earned my love and my great pity, here at the end when the woman must leave him. I had never felt such heartbreak from any book or film as I watched his great final sigh, and felt his loss and felt, also, a bit older, even wiser as the credits played. We were both transformed.

A fine, epic production, yet only 117 minutes long (that kind of powerful mega-movie would be closer to 3 hours if made today – that conciseness a lost art?) Directed by William Dieterle, staring Laughton, Maureen O’Hara, Edmund O’Brian and Thomas Mitchell. I love it.

October 10, 2016

10 Movies That Made Me Me - Movies 3 and 4

These are films I saw between the ages of ten and twenty, films that, in some way, hit hard and went in deep and mattered, enhancing or awakening some strong feeling in the boy I was then and helping to shape the man I am now. They are in no particular order.

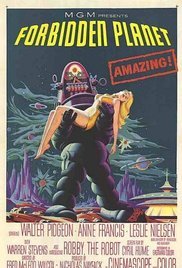

Movie 3 - FORBIDDEN PLANET, ’56(Sexuality)

I was fifteen and unworldly, shy and private, laughing at the ‘dirty jokes’ told by my friends, but awed by sex itself as a mysterious, growing power in my mind and my body. If kissing is considered first base, I had made it there only a couple of times and no further. I read paperback adventure books and was thrilled by each torn bodice or revealed thigh. I dreamed of rescuing half-clad women and becoming their gentle hero, and on the movie screen I watched these scenes like a hungry boy at a bakery window.

“Forbidden Planet” offered my 15 year old self weird music, a future universe of space travel, an intricate plot, some scenes of action, but all of this faded away even as I was leaving the theater, because there was only one offering that really mattered to me and that was the lovely Anne Francis wearing a series of very short dresses – mid thigh -- in the fifties!

She played a girl of 19, an earthling, an innocent, stranded on a planet with her scientist father for many years – and now a crew of military spacemen from earth have come to ‘take them home.’ All she had to do, for me, was stand there. She was her own light. I was the moth. Often, when she moved, I kept track of the hem of her short dress, kept track of those bare legs, and I was more than smitten. I was aroused.

Then there comes a moment where she faints or is hurt, and the astronaut hero, Leslie Nielsen, has to pick her up and carry her – and he does this by placing one arm along her back and placing the other arm beneath her thighs, and he lifts her and walks with her, and I’m thinking, my god, he’s actually touching those thighs, actually holding…. But wait. Wait a minute. This scene that I remember as being so striking, so unbelievably sexy – isn’t even in the movie! No. It’s not there. I just rewatched the film last night, and I did this because of all these ten movies in this series, Forbidden Planet was the one I remembered the least – as far as plot and dialogue and storytelling, and I thought I’d school myself in the details and then…see that mighty scene again, the one that supercharged my teenage libido, but it’s not there!

I must have received a suggestion of this ‘carrying-of-my-dream-woman from the film’s poster, which shows Anne Francis being carried this way by the robot in the film (‘Robby’), but that scene, also, does NOT APPEAR IN THE FILM. So that means I created it in my mind. I imagined that scene. I imagined me, and not Leslie Nielsen, performing that scene. I imagined the feel of lifting her, being her rescuer, and…feeling the touch of those bare legs – and because all those feelings felt so strong and true, I have spent years replaying it in my mind, believing it was there, in the film.

I was shocked last night by this realization and also smiling and shaking my head and thinking about that thunderstruck 15 year old me, and realizing how very powerful and evocative film can be – in our minds, in our dreams.

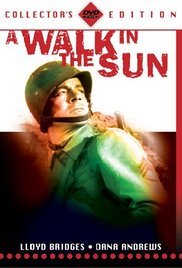

Movie 4 - A WALK IN THE SUN, '45

(The Human Truth)

Like many of the films in this series, I saw this movie not in the theaters but on early television in the late forties and the fifties. The stations had little programming at first and so played the classic and not so classic films over and over, and I was kidnapped by this particular World War Two film, and am still vulnerable to its spell.

It has a few hokey elements (it starts with a song) but it came out after the war and was not pushed toward jingoism but allowed to be faithful to it’s source, the short novel by Harry Brown Jr. – who was a combat veteran and who wrote the screenplay and, for me, offered up the human truth inside the ‘adventure’ and the ‘glory’ that made up most of the war stories I had seen on film – and I was a great fan of war stories, which led to a deep interest in military history that continues even now.

I love the simplicity of the story, one day in the life of one platoon, as they approach their landing on a beach in Italy, as they dig in during the dawn hours, as they begin their mission. They need to capture a German-held farmhouse that oversees an important bridge, but this is more than the engrossing story of that mission and its violence and its cost. The real strength here is the very human observation, the inner story of these men and boys as they move (and sometimes fight) their way toward their objective. The film’s power is in the individualizing of the soldiers, listening in on their conversations, hearing their fears and their humor, their bitterness and friendship – so different from the many films of the time that glorified the conflict and demonized the enemy.

The audience gets to know these soldiers as people as they rise or break under pressure, as they joke and curse and are wounded and lose friends and keep moving on, talking over the bits and pieces of each of their lives.

A soldier is slightly wounded and is okay to be left alone, since the American forces are moving up from the beach and will be along soon to help him to an aid station. A younger soldier asks the wounded man if he will take a letter the youth has written home and will post it. The wounded soldier says yes. The platoon moves on. Later as they take-five along the road and sit or lie down, one worldly soldier teases the youth, saying that wounded man is probably reading his letter right now. “He wouldn’t do that,” says the youth. “Sure he would, and then he’ll probably use the letter on his wound, stuff it into the bullet hole.” “He can’t do that!” Says the youth. “You can’t use paper for a wound!” “Hell, why not,” asks the other soldier, and the youth says, “Cause it crinkles!”

The platoon is staffed with a long list of good actors who create these very human individuals and take you inside of them: Dana Andrews, Lloyd Bridges, Richard Conte, John Ireland… I’ve gone along on their mission a dozen times and will go again – and I’ll read through Harry Brown’s book again, too. Somewhere inside, I’m always that boy who was me, marching along with these soldiers and witnessing their human truth as they move on toward their hellish hour at that farm house. (Directed by Lewis Milestone.)

October 3, 2016

10 Movies That Made Me Me - Movies 1 and 2

These are films I saw between the ages of ten and twenty, films that, in some way, hit hard and went in deep and mattered, enhancing or awakening some strong feeling in the boy I was then and helping to shape the man I am now. They are in no particular order.

Movie 1 - TUNES OF GLORY, ’60(Deep inner conflict)

There is a power struggle in a Scottish regiment whose base is near a town. This is during peacetime, not long after WWII. No battles, except a battle of wills, between the popular, up-from-the-ranks acting colonel who leads with a swagger and is one-of-the-men, and a full colonel who comes to take over, a more upper class man, not a martinet, but much more strict.

Does this seem predictable? It’s not. First, there’s the brilliant casting. The tough and swaggering acting-colonel is played by Alec Guiness in a real change-over, even for this great chameleon actor. The new full colonel is played masterfully by John Mills: Two of Britain’s finest actors squaring off, and, even for a young man of nineteen, I was made aware of what the quality of performance was all about (as well as crisp writing and direction).

These two men came vividly alive to me as I dropped down into the center of their struggle. My allegiances to the characters shifted, my emotions were mixed and battling each other. The Guiness character had spent the war in combat in the desert, rising from a ranker. The Mills character had been captured and interred in Japanese prison camp. There are no flashbacks to this. We learn it. We glean it. And we watch the two men as they struggle, and there, in the theater, at nineteen, I’m jerked away from the usual hero-villain story, and find myself face to face with complex and confounding human drama and human truth, shocked in the third act and wrenched by the long, slow, ending scene.

I was wrung out by this film experience, and I treasured it, and I still do. I’ve watched the movie half a dozen times over the years and will see it again – a drama without a hero, a story as unpredictable as life. Directed by Ronald Neame, staring Guiness, Mills and Susannah York. Written by James Kennaway from his novel. An early lesson for me in the richness of quality drama.

Movie 2 - BLACKBOARD JUNGLE, ‘55

(Facing the fears)

The film startles immediately because of the music: “Rock Around the Clock,” arguably the birth of Rock and Roll to my generation and so powerful in its newness, and its rebellious abandon. An urban high school – the students arriving, the teachers, the new kids, the ‘good’ kids, the ‘mean’ kids and me, one of them, because at 14 I was just entering high school, and I was shy, nervous, afraid of not fitting in, afraid of the shaming of bullies, so that here, on the theater screen, I was pulled into a gripping drama that was one hell of a training film.

The film looked raw and real with the usual muscular direction from Richard Brooks, and it came at us during the wave of the JD craze. Juvenile Delinquency was made more frightening to America than the atom bomb, and out of the deluge of that genre arose classics like The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause and Blackboard Jungle, whose trailer used the phrases ‘Teenage Terror in the Schools!’ and ‘Teenage Savages!’

But the ‘bad kids’ weren’t monsters – that would have weakened its punch. And Glen Ford, the new teacher, a married war vet, wasn’t pure and untested – he was just a good man, hoping to do his best. The head bully among the students, Vic Morrow, had a relaxed danger about him, embodying the kind of pleasure-in-your-pain that was a 14 year-old’s nightmare. His stooge was played by a boy who went on to be a fine director, Paul Mazursky, and there was one, strong, independent student played by Sidney Poitier, who knew the streets but also seemed to have a brain and a heart.

I felt the tension as if I myself was walking into Glen Ford’s first class. I was studying for my future, nervous as hell, and looking for tips. I watched as one teacher, Richard Kiley, paid dearly for trying to become the students’ friend and share his record collection with his class – by the end of this scene the precious records are broken and so is Kiley. A pretty, but not overtly sexy woman teacher was also punished – just for her natural attractiveness, which got her pounced upon and terribly shaken. Other teachers were either very tough or very cynical, but Glen Ford kept trying.

I walked the halls with those kids and fell in with some of the humor and took on the pain and panic of the tougher moments, and I began to see…a shifting among the members of Ford’s class. I felt it too. He was gaining trust and respect from them and from me, and Potier was becoming an ally without losing his independence or his cool.

As the power shifts away from Vic Morrow, he strikes out with more evil and mayhem, and all this comes to a head in a scene of violence in the classroom. All the students are involved, me too, watching and not breathing – and learning.

Yes, those bullies populating my mind could be defeated – and not by some chance heroism but rather by a shift in attitude by the other students, a standing up, a standing together. I went ahead into high school with some gained confidence and a road map and the knowledge that there would be people to support me and teachers who cared, and maybe a Poitier to calm me and help me find my way.

#