Adam Chamberlain's Blog, page 4

April 27, 2014

Frasier “Good Grief”

Title: Frasier “Good Grief”

Writers:

Director:

Network: NBC

Original Airdate: 24 September 1998

Comedy and mental health can make for strange bedfellows. There is a significant danger that, in rending humour from situations or characters featuring mental illness, the condition itself is belittled or merely ridiculed as part of the process. It could be argued that Frasier (1993-2004), the long-running and extraordinarily successful sitcom centred upon neurotic psychiatrist Dr. Frasier Crane (), risks walking this line more than most. Yet the bulk of its humour comes not from the plights of his patients but from Frasier himself and, in the example of “Good Grief”, the series’ sixth season premiere, less from Frasier’s mental struggle than it does from his hubris coupled with his inability as a mental health professional to deal with the ups and downs of his own day-to-day life.

I was at an event at Daunt Books in Marylebone a couple of months ago in which psychoanalyst turned author Stephen Grosz discussed his excellent book “The Examined Life“. In answer to an audience member’s question, he explained that one of the most simultaneously rewarding and infuriating aspects of his work is when he has been able to help resolve a difficulty in one of his patients’ lives that he has been unable to address in his own. This was so often the case for Frasier Crane and, for that matter, his neurotic brother and fellow psychiatrist, Niles (). Frasier’s likability in spite of his often snobbish and pompous nature comes from the vulnerability that this fundamental character flaw lends him, and to which we can more readily relate.

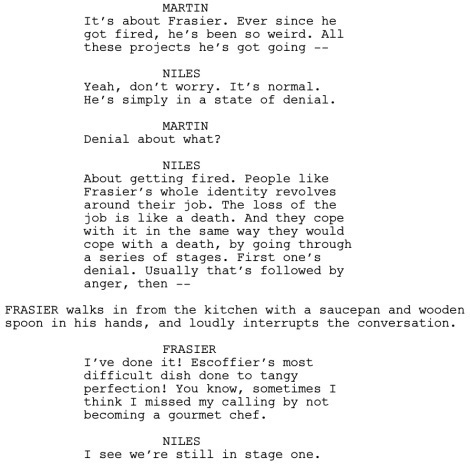

“Good Grief” rejoins Frasier and his work colleagues from talk radio station KACL in the wake of them all being fired as a result of a principled but misguided protest he had led against the station’s bosses. Frasier is auditioning for new jobs, and otherwise busying himself with all kinds of activities—such as writing an operetta—to fill his now empty days. He is in a classic state of denial, and his behaviour starts to concern his father, Martin ():

The Kübler-Ross model describes five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. The theory was first presented in 1969 by Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her book “On Death and Dying” and, whilst not universally accepted, has proven useful to therapists working with those suffering any kind of significant loss. Whilst not presented as a consistent process that those who experience grief will necessarily always undergo, the five stages are presented by Frasier in precisely this order and signalled to the viewer via the series’ trademark title card inserts—often to comedic effect in their own timing.

Frasier moves from denial into anger at a picnic he organises for his former colleagues, tipped into rage on finding that seemingly everyone save for him and his ex-producer Roz () have found employment elsewhere. He gets carried away demonstrating to a child how to strike a donkey piñata, and a pitiful scene follows in which he takes out his frustrations on it in front of the shocked and embarrassed crowd.

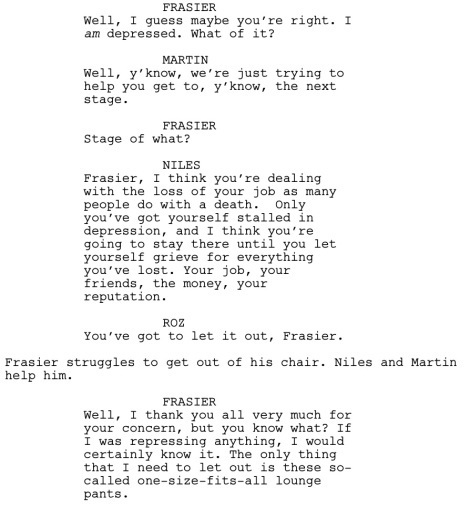

Following a party he later hosts at his apartment for his fan club—all three of them—that represents a bargaining phase, Frasier then enters a period of depression that he is unable to escape. His rut in this phase demonstrates that the experience of grief is distinct for each individual. It is also quite evident that he has put on weight from comfort-eating. Concerned, his family and friends do their best to intervene:

Supported by his family and friends—whose dialogue serves to educate the audience even as it entertains with its punchlines—Frasier sinks into a tearful period of despair before turning a corner. Some time later, he meets with Niles at their favourite local coffee shop, Café Nervosa. Here, it is clear that Frasier has reached the acceptance phase, and is getting his life back on track. What the episode effectively portrays—and without ever feeling exploitative given its choice of situation—is that certain stressful, life-changing events can unbalance anyone’s mental health temporarily as indicated by Kübler-Ross’s influential grief model. In Frasier’s case this has been the loss of his job, whilst the final scene’s punchline brings the theme full circle as it indicates it might just apply to Niles’ imminent divorce:

April 13, 2014

Doctor Who “Vincent and the Doctor”

Title: Doctor Who “Vincent and the Doctor“

Writers:

Director:

Network: BBC One

Original Airdate: 5 June 2010

Doctor Who has a unique ability to transport itself not only anywhere in space and time but also in terms of dramatic shifts in genre, style, and content. Towards the end of the first year of the Eleventh Doctor‘s () remarkable era, his encounter with celebrated but troubled painter Vincent van Gogh () remains a stand-out instalment.

Notably following an adventure in which companion Amy Pond‘s () fiancé Rory has been swallowed by a crack in the universe and therefore ceased to exist, the Doctor takes Amy to meet van Gogh after seeing a monster lurking in his painting “The Church at Auvers“. They encounter Vincent as a man vilified and outcast by his peers, befriending him as they seek out the creature, which turns out to be invisible to all but the painter’s unique visual perspective upon the world.

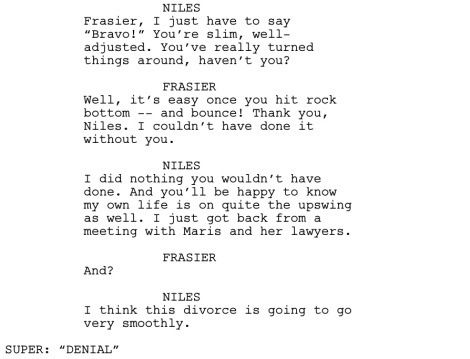

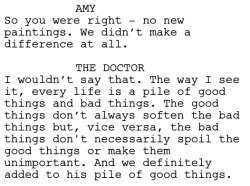

Vincent Van Gogh was undoubtedly a man misunderstood in his own time: his paintings unappreciated, and his suspected bipolar condition unrecognised. He died aged just 37 from a gunshot strongly suspected to be self-inflicted, his suicide coming at the end of a profoundly creative period during which he completed many of his best-known works. The Doctor and Amy encounter him a matter of weeks before the end of his life, and soon see him at his lowest ebb. The Doctor tries to encourage him to come to Auvers and paint the church so they can find the monster from the painting, but finds the man bed-bound and distraught. Van Gogh’s emotional response puts the Doctor uncharacteristically on the back foot and not at all in control of the situation:

The painter does join the Doctor and Amy soon afterwards, however, and if his violent shifts in mood are perhaps too frequent to represent anything but rapid cycling or a mixed state, they do offer an informative cross-section of symptoms characteristic to bipolar disorder.

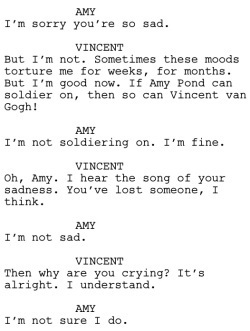

What Richard Curtis‘ script so masterfully achieves is a story rich in content but with a unified theme. Chiming with the series’ arc, Amy retains no knowledge of Rory now that he has ceased to have ever existed, with only the Doctor doing so and seeking to compensate (hence their visit to the gallery in the first instance). Yet, in conversation together on the road to Auvers, Vincent is shown to have a strong empathic sense of her inner sadness, even as it sits just beyond her own understanding:

This tender moment is also insightful in terms of human psychology. As any psychiatrist will attest, we are often unaware of the driving forces underpinning our own moods and behaviour. Rory’s apparent death and his absence from Amy’s memory is utterly supernatural and beyond her comprehension, yet it reflects an everyday truth common to us all.

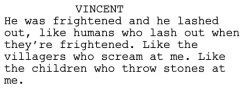

The aforementioned monster of the episode, the Krafayis, also fits perfectly with the focus upon mental health. Invisible, misunderstood and feared—like so many mental illnesses—the creature is ultimately revealed to be alone and itself afraid. Blind, it has been abandoned as weak and of no further use by others of its kind. The Doctor, Amy and Vincent discover this too late, after the creature has been mortally wounded in their final encounter with it. Again, it is Vincent’s dialogue that frames the comparison between their behaviour towards it and the villagers reaction to him:

A further area of focus in the episode is, understandably, van Gogh’s creative genius. Background information for the episode reveals that Curtis’ original concept was to suggest that certain people—including great painters—had a heightened perception and ability to see monsters, and that these monsters are more common in the world than most of us realise. Again, this can be seen as a comment upon mental illness, given that one in four of us is affected in any given year.

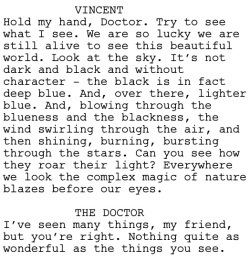

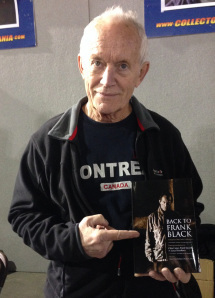

His idea does still persist in the episode, to a fashion. In a beautiful sequence Vincent, the Doctor and Amy lie on their backs and gaze up at the night sky and, as the painter describes how he perceives it, masterful effects transform the heavens into a version of “Starry Night“. Even as the scene plays out, it is easy to relate van Gogh’s elegant dialogue to some of the heightened senses associated with hypomania:

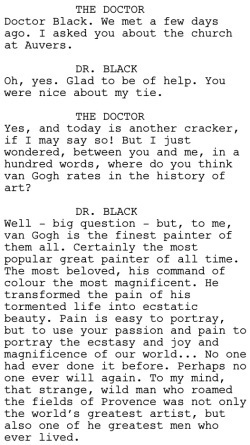

In another uplifting and emotional sequence typical of Curtis’ work, the Doctor and Amy resolve to bring Vincent van Gogh to our time and the museum exhibiting his art so that he can appreciate how beloved his body of work came to be posthumously. As the painter lurks within earshot, the Doctor finds museum expert Dr. Black () and asks him to sum up the painter’s career:

Black’s dialogue here is again beautiful, and also nuanced. All too often, though, sufferers of mental illness are shown onscreen to merely benefit from their condition: they have insight and abilities that set them apart from and above the rest of us. Whilst perhaps of comfort to fellow sufferers, it can offer an unhelpfully one-sided perspective. Not so in this instance, though, as “Vincent and the Doctor” has a sting in its tale yet.

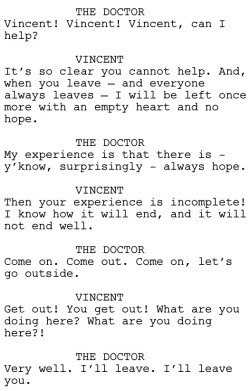

After returning a newly invigorated and inspired Vincent van Gogh to his own time and place, Amy is eager to return to the exhibition to see the new paintings that he will have produced in his longer life on a newly revised timeline. The Doctor, wisely, is less convinced, and his fears are borne out when it becomes clear that the painter still took his own life at the same time in history, his career still ending just as prematurely. Amy is forlorn, yet the Doctor seeks to offer her words of consolation:

This is confirmed when Amy finds one of his “Sunflowers” series of paintings now dedicated to her. Yet, in truth, the story ends on a remarkably downbeat note for Doctor Who. In comparison to the resolution in most episodes, here the Doctor is hardly victorious at all. He and Amy have succeeded in ensuring that van Gogh was not killed by the Krafayis, and were able to comfort the unfortunate, misunderstood creature in its death throes. The duo got to spend some time with the great painter, to inspire and be inspired by him, but otherwise the lesson is that not everything can be fixed.

Herein is a powerful and truthful message. There is no miracle cure for mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder: no drug, no therapy that can take it away permanently. For some it can be managed successfully in the short or longer term, but for others it leads to a tragic loss in quality of life, or of life altogether. The Doctor adds words of hope and encouragement, broadening the context to talk about everyone’s life having its ups and downs, albeit less dramatic or potentially harmful for most. To bring such a perspective to the fore in any drama—let alone a family show with all its trappings and high entertainment remaining intact—is a bold move, and one to be resoundingly applauded.

March 16, 2014

Silk Series 3 Episode 1

Title: Silk Series 3 Episode 1

Writers:

Director:

Network: BBC One

Original Airdate: 24 February 2014

Silk (2011-14) is a primetime drama for BBC One set in the world of a London legal chambers whose barristers compete professionally with one another in order to gain the rank of Queen’s Counsel (QC), termed “taking silk”. Writer Peter Moffat drew upon his own considerable experience from working at the Bar in creating the series, and this lends the drama an authenticity and gravitas that underpins its tales of moral dilemmas, courtroom politics, and the complex personal lives of its ensemble of barristers and clerks, as well as those of the clients they represent.

This series opener focusses upon Martha Costello QC (), and quickly establishes her distrust in and contempt for the police as she fails to win an appeal for a client she believes to have been framed by the investigating officers. This proves informative when she soon afterwards finds herself defending her Head of Chambers’ son, David Cowdrey (), after he is arrested during a kettling incident at a demonstration and charged with killing a police officer in a violent outburst.

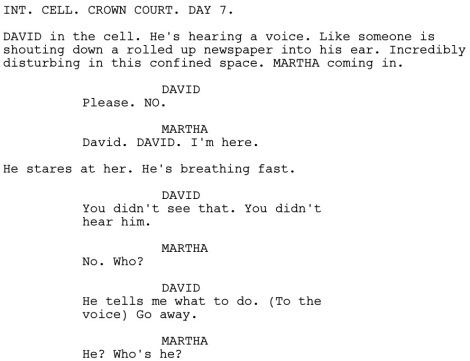

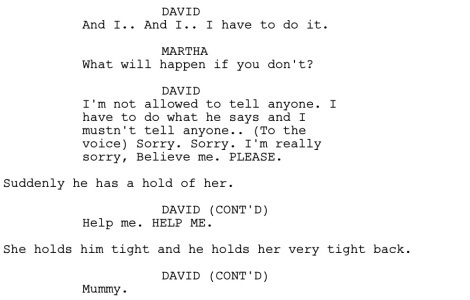

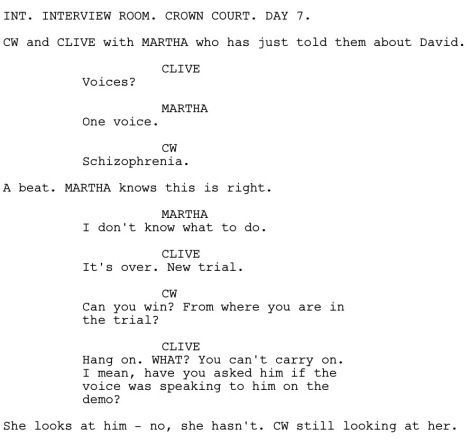

Tensions between the legal team and the police run high under the circumstances, and are further compounded by David’s behaviour, as he finds it seemingly impossible to open up to Martha and intimates that someone is threatening him in his cell. At first his reactions are perceived as those of a frightened young man being held in custody for the first time in his life but then, in a private conversation during the trial in which Martha tries once again to get him to open up to her, she comes to realise that he is suffering from schizophrenia:

Schizophrenia, a psychotic disorder that leaves sufferers unable to distinguish between real thoughts and sensory information as opposed to their own imaginings, is arguably one of the most misunderstood and oft-misrepresented mental disorders of them all. Hearing voices, as David is revealed to do, is not uncommon, and is well-represented here as a deeply unsettling experience for the sufferer in a scenario that is also seminal to the unfolding drama.

Schizophrenics are also often represented as violent, whilst in reality they—and those with mental health problems in general—are significantly more likely to be the victims of crime than its perpetrators. It is unfortunate, then, that the main storyline of this episode centres upon David’s killing of a police officer. It is revealed that he acted under duress and extreme anxiety, having been targeted by the police after he took photos of an undercover officer in the crowd, but his reaction is undeniably one of extreme violence. It is unhelpful to see primetime drama act to reinforce such a corrosive stereotype.

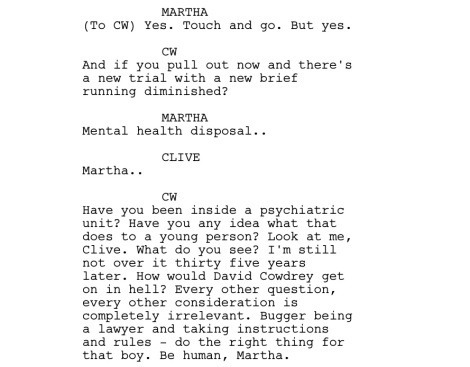

Perhaps of more interest is what happens next. Martha consults with two colleagues, Clive Reader QC () and Caroline “CW” Warwick QC (). It is clear from their discussion that if Martha reveals David’s schizophrenia to the court then the case will be dismissed and a retrial would take place, the result of which would almost certainly involve David being taken into psychiatric care. The barbed and straight-talking CW steps in to suggest to Martha that she should avoid this at all costs, revealing for the first time her own damning experience on a psychiatric ward as a teenager, from which she has never fully recovered:

Martha follows CW’s advice and goes on to win the case for David having been able to prove that the police have tampered with evidence and documentation in order to seek a certain conviction. In this somewhat uneven instalment of an often excellent series, the representation of schizophrenia is a confused one—at times sensitive, but also misrepresentative in terms of David’s deadly outburst. It delivers a damning if sensitive indictment, too, of institutions designed to help sufferers through their psychotic episodes, even though CW has gone on to have a very successful and high-functioning career. And yet it also ends on a hopeful note, as the career-driven Head of Chambers, Alan Cowdrey (), ultimately elects to sacrifice his distinguished career in order to be there for his son. They face an uncertain future as a family, but they at least do so informed by the nature of the difficulties they must overcome.

This episode is available to viewers in the UK through the BBC iPlayer until 30 March, and the script is available to download from the excellent resource that is the BBC Writers’ Room.

Silk Series 3, Episode 1

Title: Silk Series 3, Episode 1

Writers:

Director:

Network: BBC One

Original Airdate: 24 February 2014

Silk is a primetime drama for BBC One set in the world of a London legal chambers whose barristers compete professionally with one another in order to gain the rank of Queen’s Counsel (QC), termed “taking silk”. Writer Peter Moffat drew upon his own considerable experience from working at the Bar in creating the series, and this lends the drama an authenticity and gravitas that underpins its tales of moral dilemmas, courtroom politics, and the complex personal lives of its ensemble of barristers and clerks, as well as those of the clients they represent.

This series opener focusses upon Martha Costello QC (), and quickly establishes her distrust in and contempt for the police as she fails to win an appeal for a client she believes to have been framed by the investigating officers. This proves informative when she soon afterwards finds herself defending her Head of Chambers’ son, David Cowdrey (), after he is arrested during a kettling incident at a demonstration and charged with killing a police officer in a violent outburst.

Tensions between the legal team and the police run high under the circumstances, and are further compounded by David’s behaviour, as he finds it seemingly impossible to open up to Martha and intimates that someone is threatening him in his cell. At first his reactions are perceived as those of a frightened young man being held in custody for the first time in his life but then, in a private conversation during the trial in which Martha tries once again to get him to open up to her, she comes to realise that he is suffering from schizophrenia:

Schizophrenia, a psychotic disorder that leaves sufferers unable to distinguish between real thoughts and sensory information as opposed to their own imaginings, is arguably one of the most misunderstood and oft-misrepresented mental disorders of them all. Hearing voices, as David is revealed to do, is not uncommon, and is well-represented here as a deeply unsettling experience for the sufferer in a scenario that is also seminal to the unfolding drama.

Schizophrenics are also often represented as violent, whilst in reality they—and those with mental health problems in general—are significantly more likely to be the victims of crime than its perpetrators. It is unfortunate, then, that the main storyline of this episode centres upon David’s killing of a police officer. It is revealed that he acted under duress and extreme anxiety, having been targeted by the police after he took photos of an undercover officer in the crowd, but his reaction is undeniably one of extreme violence. It is unhelpful to see primetime drama act to reinforce such a corrosive stereotype.

Perhaps of more interest is what happens next. Martha consults with two colleagues, Clive Reader QC () and Caroline “CW” Warwick QC (). It is clear from their discussion that if Martha reveals David’s schizophrenia to the court then the case will be dismissed and a retrial would take place, the result of which would almost certainly involve David being taken into psychiatric care. The barbed and straight-talking CW steps in to suggest to Martha that she should avoid this at all costs, revealing for the first time her own damning experience on a psychiatric ward as a teenager, from which she has never fully recovered:

Martha follows CW’s advice and goes on to win the case for David having been able to prove that the police have tampered with evidence and documentation in order to seek a certain conviction. In this somewhat uneven instalment of an often excellent series, the representation of schizophrenia is a confused one—at times sensitive, but also misrepresentative in terms of David’s deadly outburst. It delivers a damning if sensitive indictment, too, of institutions designed to help sufferers through their psychotic episodes, even though CW has gone on to have a very successful and high-functioning career. And yet it also ends on a hopeful note, as the career-driven Head of Chambers, Alan Cowdrey (), ultimately elects to sacrifice his distinguished career in order to be there for his son. They face an uncertain future as a family, but they at least do so informed by the nature of the difficulties they must overcome.

This episode is available to viewers in the UK through the BBC iPlayer until 30 March, and the script is available to download from the excellent resource that is the BBC Writers’ Room.

March 2, 2014

Northern Exposure “Three Doctors”

Title: Northern Exposure “Three Doctors“

Writers:

Director:

Network: CBS

Original Airdate: 20 September 1993

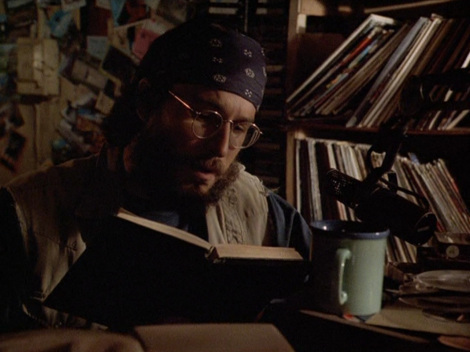

Northern Exposure (1990-95) is an utterly unique creation. Set in the fictional town of Cicely, Alaska, it charts the interactions between Joel Fleischman (), a New York doctor repaying the state’s sponsorship of his education by serving out an assignment as the town doctor, and its quirky array of inhabitants. Its storytelling is quite gentle for the mostpart, unfolding poetic, whimsical and highly-literate stories on a weekly basis across six seasons of exquisite television. John Cody, a San Franciscan professor, once wrote that its episodes “consistently exhilarate us, the viewers, by honouring our capacity to delight in, to relish the play of intelligence and psychological nuances. Each drama serves a wonderful ten-course gourmet banquet for our starved imaginations: magic, myth, ritual philosophy, religious wisdom, folklore, fantasy, and living sparks from the moral dialectics of diverse characters”.

Many of these qualities are evident in the series’ fifth season opener, “Three Doctors”. In something of a trademark structure, three separate story strands reveal a unifying theme. Joel comes down with a case of “glacier dropsy” (a.k.a. “tundra fever” or “Yukon ague”), a virus that he has never heard of, and the very existence of which he refuses to acknowledge until such acceptance informs a turning point in his recovery. Movie-obsessed Native American Ed Chigliak () experiences bouts of “sleepflying”, waking up in trees or on the roof of the town bar, The Brick, with no knowledge as to how he came to be there, and ultimately learns that this is as he is being called to become a shaman. And co-owner of The Brick, Shelly Tambo () learns that her involuntary and constant voicing of everything she says in song relates to her innermost feelings about her pregnancy.

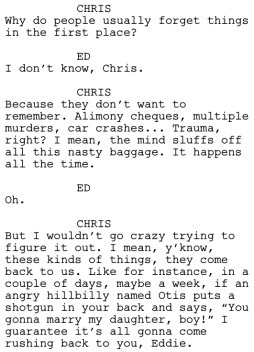

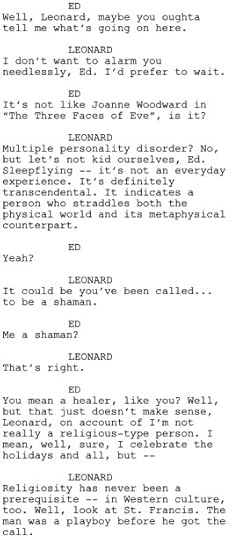

What unites each character is their dissociation from the reality of their circumstances. In an early scene, Ed visits Chris Stevens, resident disc jockey and philosopher, to seek his advice as to why he cannot remember his sleepflying episodes. After ruling out drink or a hit to the head, Stevens suggests that such apparent forgetfulness is not such an unusual mental state:

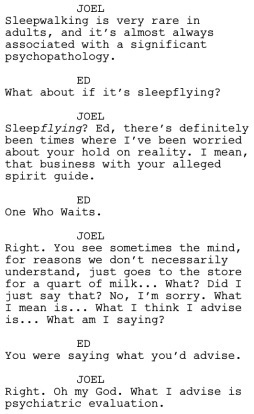

Cicelians habitually normalise behaviour that some might consider more obtuse, and this attitude represents one of the series strengths: its openness and its spirit of universal acceptance. Cicely feels like such a welcoming place to visit, and this is key to the series’ attraction. Moreover, it is an important and worthy mindset to champion. Dr. Fleischman’s attitudes are often shown to contrast with those of the townsfolk—although he slowly comes to embrace Alaskan life as the series develops—and, when Ed visits his surgery for a consultation before Joel becomes bedridden, he offers something approaching a more conventional medical opinion, even as he struggles to resist his own progressive delirium:

Sleepwalking has a number of potential causes, ranging from a physical illness through anxiety, trauma, to mood disorders such as bipolar, or some form of psychosis. In terms of available treatments, various talking therapies have been developed, and medication is recommended as a short-term and last-resort option only. So Dr. Fleischman’s advice is sound. He would, however, be less than enthused with the form that evaluation takes.

The wonderfully-portrayed character of Leonard Quinhagak () is a local shaman that is set to become something of a mentor to Ed. In order to explore the underlying reason for his sleepflying, he leads him out into the breathtaking Alaskan wilderness to perform a somewhat unusual diagnosis that involves burying Ed’s fist in the ground overnight, to see what manifests. Ed is understandably eager to learn more:

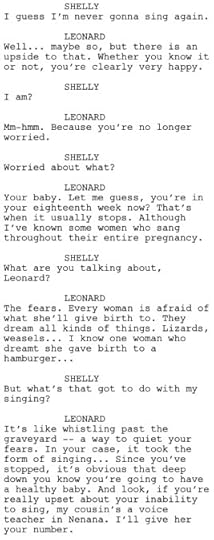

Leonard displays a refreshing and pragmatic mix of Native American traditions and more modern Western culture, and it is this spirit of cross-discipline inclusivity that the script invites. Ed makes a clumsy but notable attempt at explaining to Shelly why her uncontrollable singing has stopped as suddenly as it began, drawing upon his encyclopaedic knowledge of cinema by offering a comparison with the excellent Awakenings (1990). The Academy award-nominated film, based upon Oliver Sacks‘ memoir, tells of how fictional neurologist Malcolm Sayer () manages to temporarily bring some patients—including one Leonard Lowe ()—out of a catatonic state through innovative drug therapy, before their recovery suffers a heartbreaking setback. It proves not to be such a comforting comparison, but Leonard’s own brand of therapy subsequently provides Shelly with the closure that she needs, and that allows her to embrace the forthcoming birth of her first child with a fresh optimism:

It would be inaccurate to suggest that “Three Doctors” in any way offers a realistic portrayal of a dissociative disorder, although Ed does suffer from a form of amnesia, and Joel experiences a distorted view of his surroundings in his fevered state, including a vision of a medical colleague appearing in his home and having an imaginary conversation with him when he is merely on the other end of a phone line.

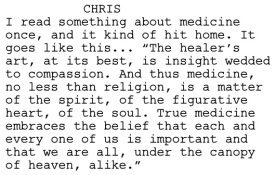

In keeping with the tone and style of Northern Exposure, though, this is not its intent. Rather, through its mix of gentle drama and quirky comedy, it makes us consider the emotional truths that belie the improbable situations of its characters. What “Three Doctors” so successfully promotes is an accurate portrayal of mental health difficulties as commonplace and with the potential to affect anyone, plus an individualistic approach in the treatment of such conditions. Such an attitude is summed up beautifully in a passage Chris Stevens reads over the airwaves towards the episode’s denouement:

February 23, 2014

Homeland “Pilot”

Title: Homeland “Pilot”

Writers:

Director:

Network: Showtime (USA)

Original Airdate: 2 October 2011

The hugely popular and critically acclaimed psychological thriller Homeland prominently features mental health issues from the very outset at the core of each of its two lead characters. Brilliant CIA analyst Carrie Mathison () struggles to hide her bipolar diagnosis from her employers, whilst returning and conflicted war hero Nicholas Brody () is suffering the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following his eight year imprisonment in Iraq.

We first meet Carrie on the streets of Baghdad, putting herself in severe danger as she bribes her way into an Iraqi prison so as to learn vital intelligence from an informant who is about to be executed. Such risk-taking is soon evident to be quite the norm for Carrie, as she seeks to confirm her suspicions about Brody’s loyalties in the wake of the intelligence she receives. Even as he returns home to a hero’s welcome, she enlists fellow operative Virgil () to illegally bug Brody’s home, and later pursues an aggressive line of questioning during his initial debrief.

Whilst such scenes highlight the difficulties that being bipolar can represent in the workplace, perhaps one of the challenges to the believability of Homeland‘s premise is the fact that Carrie Mathison has been able to gain and retain such a demanding position in the CIA at all. Following feedback from a focus group to an early version of the episode, the scene in which Carrie questions Brody was re-shot so that her mania was not so evident, and a subsequent meltdown that she suffered immediately afterwards was edited out completely (although the footage survives as a single deleted scene on the DVD release). The concern was that, in order to retain her credibility at work, her most vulnerable moments should only be witnessed in her private realm. This topic is also addressed head-on by a conversation between her Division Chief Saul Berenson () and Director David Estes () in which they discuss Carrie in the wake of Brody’s debrief:

As well as highlighting the tensions Carrie’s behaviour causes with her employers due to her unpredictable behaviour (not to mention her habitual lateness), this scene is punctuated with the implication that she once had a sexual indiscretion with the now Director of the CIA. Another key moment towards the end of the episode sees Carrie make a pass at Saul in a misguided attempt to smooth things over after he finds out about her illegal surveillance on Brody and threatens her with disciplinary action; the scene establishes Saul as a man of integrity as he immediately and vehemently rebuffs her approach.

Both an increased sex drive and risk-taking are behaviours associated with the manic episodes of bipolar disorder, although their prominence in this episode probably owes more to how they serve the plot and to deliver heightened drama than it does to offering a fully-rounded portrayal of Carrie’s illness. Looking back, the writers question their own creative decisions with this scene given how the relationship between Carrie and Saul evolves, although perhaps moments such as this contribute to the true (and non-sexual) intimacy that the pair develop.

Immediately after this confrontation Carrie suffers something of a meltdown, drawing upon elements of the scene originally written and filmed to follow Brody’s debriefing. Agitated, she lies down and listens to some chaotic jazz (carefully chosen by the writers to contrast with the smoother tastes of Saul) before determining to go out with the express intention of meeting someone for sex. In a scene set in her closet—tellingly so, as Claire Danes points out in the DVD commentary, given Carrie’s secretiveness about her condition at this point in the series—she rapidly goes through a number of choices of outfit. Again, the soundtrack—trumpeter Tomasz Stanko‘s “Terminal 7“—perfectly fits the scene’s frenetic mood. Reflecting a scene towards the start of the episode, wherein she returns home from a night out just long enough to have a “whore’s bath” and change clothes before heading straight to work, she dons an engagement ring as a cover in order to deter men seeking anything other than a casual encounter.

Another telling strand to Homeland‘s “Pilot” is the way in which Carrie self-medicates. She hides clozapine capsules in an aspirin bottle in her bathroom, with their “off-label” use in the treatment of bipolar disorder offering a further hint that the drug has not been formally prescribed to her by a medical professional. Virgil’s brother and co-conspirator finds the drug whilst seeking out something for a headache at Carrie’s house, which leads to another seminal scene in which Virgil confronts Carrie even as they are engaged in further unofficial surveillance of Brody from the back of his van:

Danes’ performance in this scene is electric, and her aggressive response is also typical of a manic episode. She feels guilt over her situation, too, later referencing that she has played her “only true friend” for a fool.

If Brody’s own conflicted nature takes a back seat in this episode, then nevertheless we witness some of the difficulties that his PTSD will inflict upon him as he is reunited with his family and subsequently tries to return to at least the appearance of a normal life. A particularly harrowing scene sees him have an aggressive sexual reunion with his shocked wife; the unease with which Carrie looks on as she continues her invasive surveillance acts to reinforce the discomfort of the audience experiencing this most private and unsettling of moments. Perhaps the need to play the dual realities of Brody’s character in order to sustain the season’s central mystery as to his true allegiance takes precedence overall in the drama, but nevertheless such unflinching moments are powerful and unusual portrayals of a debilitating condition.

Homeland has earned many accolades for both its stars and its writing, and not insignificant amongst these is the 2012 Mind Media Award for Drama, recognising those who have “abandoned stereotypes in favour of accurate portrayals of mental health”. Nevertheless, the series has gone on to attract subsequent criticism, too, for some of its later representations of Carrie’s bipolar disorder, and for at times implying a straightforward and direct link between the analyst’s supreme talents and her manic highs. These are topics to which this blog intends to return, in the context of some of Homeland‘s later instalments.

The mental health issues suffered by both Carrie and Brody are complex and multi-faceted, such that a single hour of drama also tasked with setting up the season’s complex plot and ambiguous loyalties could never hope to represent them fully. In the context of Homeland‘s accomplished and fully-formed “Pilot”, though, it is clear that nuanced writing and superb performances combine to bring these subjects to greater prominence and encourage their widespread discussion, and that in itself is no bad thing.

November 28, 2013

Copies of “Back to Frank Black” Signed by Lance Henriksen Now Available

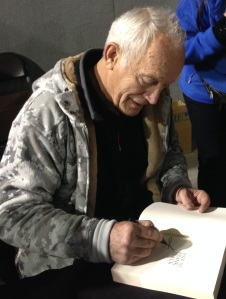

This year, we have had the great privilege of attending no fewer than three events in the UK alongside to help promote Back to Frank Black. From Glasgow to Cardiff to Milton Keynes, at each of the Showmasters-organised conventions we had copies of the volume on sale, and Lance signed and personalised each and every one on request.

For anyone who came to one of these events or, for that matter, who has ever met Lance Henriksen in a similar context, it will come as no surprise to hear just how generous he is with his time. Always attentive in his interactions with fans despite consistent crowds and often lengthy queues, he also makes for a charismatic presence on-stage when giving frequent talks and answering audience questions. He talks openly and enthusiastically about his approach to his craft as an actor—of how he “absorbs” scripts and their themes through multiple readings rather than merely learning lines by rote, for example—and is quick with a self-effacing, humorous aside.

He is often asked what his favourite role is from his lengthy list of credits, and always responds that it is the last project on which he has worked. There were hints, too, of quite how enthused he is over a yet-to-be-announced major movie he filmed earlier this year, and that is set for release in 2014. Questions are invariably posed, too, about Henriksen’s celebrated starring role in Millennium. He speaks about the role of Frank Black with passion every time, and takes every opportunity to give a shout-out for both the book and the Back to Frank Black campaign itself.

He is often asked what his favourite role is from his lengthy list of credits, and always responds that it is the last project on which he has worked. There were hints, too, of quite how enthused he is over a yet-to-be-announced major movie he filmed earlier this year, and that is set for release in 2014. Questions are invariably posed, too, about Henriksen’s celebrated starring role in Millennium. He speaks about the role of Frank Black with passion every time, and takes every opportunity to give a shout-out for both the book and the Back to Frank Black campaign itself.

In the wake of our promotional push regarding these appearances, we have received a number of queries about whether we would make available for sale any copies of the volume signed by Lance Henriksen. We are therefore very pleased to confirm that we now have available a very limited number of autographed copies. The first batch of hardcovers and softcovers are listed at Amazon.co.uk and will be shipped anywhere in the world from the UK, with all proceeds to be donated to Henriksen’s nominated charitable organisation, Children of the Night.

Our sincere thanks to Lance Henriksen for his continued support throughout 2013, and especially for taking the time to sign these exclusive copies of Back to Frank Black.

June 30, 2013

Editors Join “Back to Frank Black” Google+ Hangout

Yesterday, Back to Frank Black editors and Fourth Horseman Press publishers Adam Chamberlain and Brian A. Dixon joined the Back to Frank Black team of Troy Foreman and James McLean for their inaugural Google+ Hangout. The conversation was skilfully hosted and directed by the wonderful author and critic John Kenneth Muir, and you can now relive the entire hour-plus event on YouTube via the video embedded below.

The discussion covered the conception and writing of the book plus some reflections upon its content, as well as shared thoughts on Millennium itself. Muir asked the panel to reflect upon reasons for the series’ enduring appeal, and to imagine ways in which it might return—even the prospect of a reboot! We would like to extend enormous thanks to John for taking the time to moderate the discussion and for such thoughtful questions, and to James and Troy, too, for inviting us to take part. It was a lot of fun, and it is now our pleasure to be able to share the discussion with you right here.

April 7, 2013

Apocalypse: Now… or Never?

On Good Friday, I joined a fervent crowd at London’s Natural History Museum for an After Hours discussion entitled “Apocalypse Now… or Never?” The event tied in with their current exhibition “Extinction: Not the End of the World?” and explored scenarios and themes associated with doomsday from a scientific, literary, and sociological perspective.

One glance at the Fourth Horseman Press back catalogue should suffice to explain my interest in the subject matter: Revelation magazine concerns itself exclusively with apocalyptic art and literature, The Final Curtain examines human relationships tested by end-of-the-world scenarios across a pair of single act dramas, and Back to Frank Black explores Chris Carter’s Millennium, a series that delved into the cultural and social fears of a looming apocalyptic threat with an unparalleled depth of vision. Even Columbia & Britannia has its genre links—what, after all, is alternate history if not the tearing down of one reality to replace it with a brave new parallel world?

The speakers for this event were uniformly excellent: astrobiologist Dr. Lewis Dartnell, social psychologist Dr. Robbie Sutton, and Leila Abu el Hawa, founder and organiser of the Post-Apocalyptic Book Club. (Leila has shared a version of her introduction from the event at their website, including a photo in which you can just about glimpse me on the opposite edge of the frame to dictionary-devouring author Will Self!)

The literary references were naturally an area of particular interest, with the sheer breadth of the genre—extending into dystopian fiction—described, and familiar names such as Cormac McCarthy, John Wyndham, and Richard Matheson all quite rightly earning repeat mentions. The modern literary origins of apocalyptic fiction were traced to the nineteenth century via Mary Shelley’s The Last Man and the lesser-known Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville’s Le Dernier Homme that preceded it.

The “last man” as an anti-hero of sorts, the themes of such stories, and our identification as individuals with such characterisations of survival against the odds were all touched upon. So, too, was a recommendation for a book that was new to me: Night Work by Austrian-born author Thomas Glavinic. In addition to the likes of genre favourites The Road, I Am Legend, The Day of the Triffids and On the Beach, I was also pleased to hear a recommendation for John Christopher’s The Death of Grass, a copy of which nestles towards the top of my own mountainous to-read pile.

The erudite Dr. Dartnell is also planning his own book release: Aftermath, a survivor’s guide to living in a post-apocalyptic world. His answers to questions fielded by the audience were often as humorous as they were informative. Asked to define the threshold an apocalyptic event he quoted a colleague who would “not get out of bed for anything less than a one per cent mortality rate”, whilst also noting that—as such complex biological entities—humans are far more prone to changes in our environment than are extremophiles and bacteria, organisms the like of which might even be able to survive the harsh environment of space. He also speculated how the role of chance would likely influence society to be rebuilt differently in the wake of an apocalyptic event that fell short of wiping out human civilisation. He berated the dinosaurs’ “rubbish space program” as a factor in their extinction—albeit thankfully clearing the way for the rise of the mammalian lineage—whilst acknowledging that “even ten Bruce Willis-es” would prove ineffective against the threat of a comet impact with the Earth.

Asked to name the most likely cause of our collective demise, though, Dr. Dartnell hinted towards the ever-increasing perils of over-population as being the perfect breeding ground for a global pandemic. Cautioning that the Black Death was the closest humankind has yet come to a total collapse of civilisation, he noted that people were formerly more connected with the land than we typically are today, and that hence everyday survival skills—such as how to grow and cultivate crops—are now in short supply. Unless an apocalyptic event came with enough warning for them to prepare and to recruit resources, the survival of the rich and powerful would therefore not necessarily be favoured. A fundamental shift in the social order would result, with skills as the new currency. Those with social support and psychological would be the ultimate survivors.

The looming antibiotic apocalypse was also referenced during this part of the discussion, and there was mention, too, of the very real prospect of technology developing beyond our control, as evidenced by the fact that no one person has the complete knowledge required to build an iPhone, whilst even computers designed the chip in the iPhone 5. Not, he hastily added, that we need fear “The Rise of the iPhones” just yet.

Of most interest of all to me were the insights offered by Dr. Sutton of the University of Kent, which focussed upon the psychology underlying our preoccupation with the apocalypse, our potential reactions to such doomsday scenarios, and the strength of the human spirit to rebuild society in their wake. He postulated that the apocalypse offers the promise of a simpler way of life, and of recreating society in a more idealised form free of the mistakes many perceive we have wrought collectively upon our world.

He explained how belief in either a religious or secular apocalypse speaks to an inherent sense of fairness to our existence, or immanent justice reasoning, in which the cosmos intervenes to reset the balance. Thus, some come to incorrectly ascribe the fall of the Roman Empire to a perception of its sexual immorality, whilst the debate on climate change becomes allied to discourse on how we ravage the Earth’s natural resources. Our ambivalence for a cleansing sees destructive impulses enshrined in an apocalyptic ideal. I was put in mind of a view to which I subscribe: that our fascination with the apocalypse speaks to an existential need to add or describe shape and meaning to our own mortality.

Dr. Sutton pointed to the riots in England during the summer of 2011 and the ongoing global recession as examples where studies have demonstrated that individuals’ reactions to extreme scenarios are more likely to be selfish than altruistic. We are prone to becoming less communal, more hedonistic, and suffering from a loss of meaning and a threat to our ambitions, even as chaos and anarchism are granted meaning in the pursuance of a better, fairer society. This is arguably evidenced by the existence of at least two million “preppers” in the United States alone, bolstering themselves for self-defence in remote locations in case the social contract snaps. A more positive response to an apocalyptic scenario would be forthcoming only by uniting us in a common purpose to resist an alternative meaning, as evidenced by the Allied response to the Nazi threat in World War Two.

Conspiracy theories were also given a mention, and parallels drawn between the belief systems inherent to both them and to apocalyptic prophecy. Both are often delusional and incoherent in nature, whilst studies in this area have proven that subscribers to conspiracy theories are more prone than others to hold two contradictory beliefs simultaneously. Dr. Sutton also expressed an interest in what happens when doomsday predictions fail—as explored in the latest and landmark issue of Fortean Times, no less—and is working on a book that explores such topics. I will most definitely be seeking out a copy when it is published.

Dr. Sutton was firm in his belief that the most likely cause of the apocalypse is, simply, “us” given that we keep producing new mechanisms for the infliction of mass death. Setting aside talk of man-made pathogens and the increasing importance of biosecurity, he was also asked if the very preoccupation of popular culture with apocalyptic scenarios could in any way be self-fulfilling. He appeared to reject such a notion, pointing to the fact that the power of the concept is more fundamental even than its realisation in Biblical prophecy. He also recommended the work of author Richard Landes, former director of the Center for Millennial Studies, whose work explores “normal time” and “apocalyptic time”: the linear progress of society until a period of threat or crisis, followed by a denouement. (For Millennium fans reading this, Landes has written at length about the concepts behind the “Owls” and “Roosters”, terms that he coined.)

In sum total, this event was a fascinating discussion on actual and imagined threats to human civilisation, their cultural expression, and the psychological basis for our fascination therewith. It proffered evidence that an interest in the apocalyptic is fundamental to the human condition, and that such preoccupations have and continue to inspire us to plough deep and varied creative furrows. I was duly inspired by a wonderful couple of hours spent surrounded by the atmospheric architecture of the Natural History Museum, a building that itself resonates with the rich, fascinating multitude of life that has inhabited our planet throughout its history.

For our part, Revelation is set to make its long overdue return this year as it looks to close out its fourth and final volume. You can rest assured that evenings such as this inspire us to make those final issues cram-packed with the very best in apocalyptic art and literature that we can find.

–Adam Chamberlain

(Featured image “Apocalypse” by Josée Holland Eclipse)

November 22, 2012

Notes from Authors on “Back to Frank Black”

One of the great joys of publishing any book, after months if not years of travail, is to reveal it to its audience. In the case of Back to Frank Black—and indeed a number of Fourth Horseman Press projects—that joy is multiplied as we finally get to share the finished product with our many collaborators, authors who have worked tirelessly on a part of the whole without hitherto having been able to view the bigger picture.

In the weeks since the book’s release, some of our contributing authors have been sharing their initial thoughts on the collection, both via their own blogs and in private correspondence with us. Amongst them is award-winning critic John Kenneth Muir, who sums up Back to Frank Black as “an impressively written, edited, and presented book, featuring terrific insights about Millennium from many of those talents who made the series such a special endeavor,” adding that it “includes well-written, provocative and intriguing essays about the series and its implications.” These include no fewer than three contributions of his own, considering the themes of each season of Millennium in turn.

Paul Clark writes about the inspiration behind his own contribution, which explores how actor Lance Henriksen embodied the role of Frank Black. “The story of a life is a thin narrative, composed of events and experiences,” he explains. “However, the fable of a life is a thick narrative, filled with the deeper meaning and interior myth of who a person really is. As I read [Lance Henriksen’s autobiography] Not Bad for a Human, I began to see how the story of Lance Henriksen helped him to create the fable of Frank Black.” He also shares his own views on Back to Frank Black: “I feel the book is an amazing achievement,” adding that it is “an important addition to our knowledge of Millennium in particular, and to our appreciation of popular culture in general.”

Perhaps our favourite feedback to date is summed up in one of the comments shared by Joe Maddrey on his blog: “This book achieves such a high standard of quality that I almost can’t believe it exists.” He goes on to write extensively about the volume’s contents, so please do check out his blog entry in full. He sums up the series that inspired the collection by proclaiming, “Millennium is something profoundly unique. No doubt that’s why, thirteen years after Fox cancelled the series, it still has a strong enough following to produce a 500-page book of essays and interviews that would meet the most rigorous academic standards. I’m astounded that a fan-led campaign has not only been able to produce such a thoroughly literate work, but that it was also able to secure the involvement of nearly every major cast and crew member associated with the series—including showrunners Glen Morgan and James Wong, who didn’t even participate in the official DVD release of the series! This series, from the very beginning, asked some of the biggest, most important questions in life. Millennium is dense, meaningful literature in a visual medium.” In terms of this response to the book he concludes, “As a reader, it makes me feel like a more active part of a very meaningful world, a world that still lives on in the imaginations of viewers across the globe.”

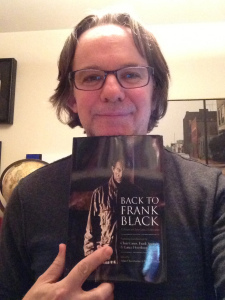

It is not only our co-authors who have been sharing their initial responses to the volume, of course, but also the creative minds behind Millennium, those who forged the character of Frank Black, his experiences, and the world he inhabited from their own blank page. Chris Carter enthusiastically received his copy at the Austin Film Festival, and Frank Spotnitz commented in a recent interview with the Back to Frank Black campaign, “It’s a beautiful book. This is what you hope for. You hope that when you do something, especially in television—which is so often disposable—that it is something that people still think about. Obviously it resonated for you guys to put all this thought and care into this book, and I think that’s the biggest compliment that we could be paid.” He also took the time to send in a photo of himself with his copy. Many of the cast and crew interviewed have offered their own kind and very complimentary and enthusiastic feedback. Leading the way amongst these is Lance Henriksen, who has been voraciously reading the collection in full and enthusing about the “promise” for Frank Black’s potential return that resonates throughout.

It is not only our co-authors who have been sharing their initial responses to the volume, of course, but also the creative minds behind Millennium, those who forged the character of Frank Black, his experiences, and the world he inhabited from their own blank page. Chris Carter enthusiastically received his copy at the Austin Film Festival, and Frank Spotnitz commented in a recent interview with the Back to Frank Black campaign, “It’s a beautiful book. This is what you hope for. You hope that when you do something, especially in television—which is so often disposable—that it is something that people still think about. Obviously it resonated for you guys to put all this thought and care into this book, and I think that’s the biggest compliment that we could be paid.” He also took the time to send in a photo of himself with his copy. Many of the cast and crew interviewed have offered their own kind and very complimentary and enthusiastic feedback. Leading the way amongst these is Lance Henriksen, who has been voraciously reading the collection in full and enthusing about the “promise” for Frank Black’s potential return that resonates throughout.

We now have a number of copies of Back to Frank Black out for review, and at some point will collect together some of this feedback here on the blog. If you have yet to be persuaded to pick up a copy of your own, we hope that these reviews—such as the one already published by Starburst magazine—might just convince you to do so. In the meantime, one way everyone who has bought a copy to date can help our cause is to leave a review at either Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk (or both)—where you can also now preview the book’s contents via Amazon’s Search Inside function. Reviews are especially important at Amazon for encouraging potential buyers not already familiar with the title or with the campaign—just the very kind of people to whom we hope this book can extend its reach regarding the campaign to return Frank Black to our screens.

Copies of Back to Frank Black are also now with a number of executives at Fox, fulfilling another part of the book’s mandate in the “manifesto”—as Lance Henriksen himself puts it—that shines out from its every page. You can expect a new drive in the Back to Frank Black campaign’s requests for you to write letters to Fox in the very near future, too, building upon the book’s momentum yet further. We will continue to share updates on the volume’s progress here, too, but for now a huge thank you to everyone who has already picked up a copy to date, and we hope you enjoy the contents.