Adam Chamberlain's Blog, page 3

November 28, 2014

The Twilight Zone “Person or Persons Unknown”

Title: The Twilight Zone “Person or Persons Unknown“

Writer:

Director:

Network: CBS

Original Airdate: 23 March 1962

Time to Change, the UK-based campaign to end mental health discrimination, this month published a report that treads very similar ground to this blog. The report, titled “Making a drama out of a crisis“, considers both positive and negative trends in representations of mental illness in drama, overall acknowledging that depictions of such characters are becoming more “authentic, sympathetic, and complex”, and that a relatively new type of narrative has come to focus upon stigma and the perils of exclusion.

It also, however, highlights a number of examples of unhelpful stereotypes being reinforced, with characters suffering from a mental illness still prone to being depicted as violent or as “tragic victims”, and “medication myths” being perpetuated that compress the time it takes for medication to have an effect, or for any effects of withdrawal to become apparent, exaggerating the notion of medication being the only viable means of treatment.

The report’s conclusions also highlight the influence of drama on people’s actions, reporting that those who know someone with a mental health problem are more likely to reach out to them after seeing such issues onscreen, and that those with a problem are more likely to seek help. Drama can and does make a very real and significant impact upon our everyday lives.

Screenwriter Peter Moffat—creator of Silk, a BBC One drama that has featured on this blog—is quoted in the report as citing the importance of truthful characters in drama, and highlights a trailblazing series that has also featured:

Drama can make a huge difference in the struggle to get people thinking about mental health properly and without prejudice. It doesn’t need to be polemical or campaigning, it only needs to be truthful. Homeland has set the standard for complex and honest writing about mental health and we all need to follow its lead. In a television era when too many documentaries are essentially freak shows written, shot and edited to ask an audience to laugh at people with mental health issues, writers of television drama have a special responsibility to work against stereotyping and to create characters who are complex and engaging. Let’s do it.”

The report is well worth a read in its entirety, whilst it also suggested to me that it was about time this blog turned the clock back further than it has done to date to consider how a celebrated, older drama would measure up today. For that reason, and given I relatively recently started watching the series in its entirety, we venture into an all-time classic and the mind-bending reality of… The Twilight Zone.

“Person or Persons Unknown” harks from the series’ third season, and is introduced by the great thusly:

The Twilight Zone is, of course, a highly influential anthology series that in many regards stands up very well today, and whose strong influence can be seen in such series as The X-Files. But, specifically, how does this instalment’s representation of mental illness fare when considered through modern eyes?

The episode focusses upon David Gurney (), a man who wakes up one morning, fully-clothed, on a bed next to his “wife” who, much to her horror, claims to have no prior knowledge as to the man in her bedroom. A similar scenario greets Gurney at his workplace, leading to his arrest. Thereafter he finds admitted to a mental hospital, where he is attended to by a Dr. Koslenko (). Koslenko engages with our increasingly excitable protagonist to try to explain that “David Gurney” does not exist:

This is about as expositional as the script gets, as befits The Twilight Zone. If we were to place a modern diagnosis upon “David Gurney”, then it would likely be dissociative fugue or dissociative amnesia. Such fugue states, during which the sufferer may assume a new identity as Gurney attempts to do here, were not unknown in the Sixties, but the shifts in diagnostic standards in the half century since “Person or Persons Unknown” was written and first aired are not to be underestimated. Yet, whilst the style of acting has certainly changed markedly over this period also, Long’s performance certainly portrays the sense of internal chaos that sufferers can endure.

It is noteworthy also that this is the third consecutive choice for this blog that features a mental hospital heavily in its plot. In “Person or Persons Unknown”, the set design and atmosphere depict a relatively welcoming, peaceful environment wherein security is so lax that all Gurney has to do in order to escape is to dive head-first through Koslenko’s office window (by all accounts something of a recurring behavioural trend in Twilight Zone)!

Key to the core tenets of The Twilight Zone, of course, is that each instalment leaves the viewer with unanswered questions and a sense of the unknown or unknowable. The series would therefore not set out to offer an explanation for conditions or circumstances such as those endured by David Gurney. Instead, it prompts the viewer to consider his or her own sense of self, even whilst it simultaneously serves to inform the viewer’s perceptions of mental health.

It is this very arena that the Time to Change report seeks to highlight, recognising and reflecting how styles and trends in storytelling continue to evolve, and how they come to inform the viewing public’s perceptions of mental health. I’m whole-heartedly with Peter Moffat on this in terms of the responsibility borne by writers, and hence the creation of this very blog. But, in 1962, Rod Serling was content to leave the viewer with a lyrical and decidedly unsettling sense of mystery, as per his closing words to the viewers at home:

October 30, 2014

Millennium “The Pest House”

Title: Millennium “The Pest House“

Writers:

Director:

Network: Fox

Original Airdate: 27 February 1998

For Halloween, and as something of a companion piece to my previous post on the Perception episode “Asylum“, I wanted to take another look at an all-time personal favourite series, Millennium. My episode of choice this time, though, is not seasonal favourite “The Curse of Frank Black“, but rather another second season instalment that again features a psychiatric hospital and its patients at the heart of the story: “The Pest House”.

Whilst not Halloween-themed, this is certainly an episode that seeks to trade on scares and, specifically, urban myths about bloody murders perpetrated by the so-called mentally-deranged. I found the original Fox trailer for the episode on my hard drive, as posted on the official site during the series’ original run. It’s impossibly grainy and low resolution—this was as good as it got in the Nineties, Millennials!—and is naturally over-dramatised in comparison with the tone of the episode itself, but it nevertheless conveys a sense of the brand of drama that the story seeks to leverage from its setting:

Penned by Season Two executive producers Glen Morgan and James Wong, “The Pest House” focusses criminal profiler Frank Black () and the increasingly sinister Millennium Group’s Peter Watts () upon the patients at the East County Forensic Psychiatric Hospital, where they come into conflict with Dr. Ellen Stoller (, perhaps better known to Ten Thirteen fans for her semi-recurring role in The X-Files as Dana Scully‘s sister, Melissa).

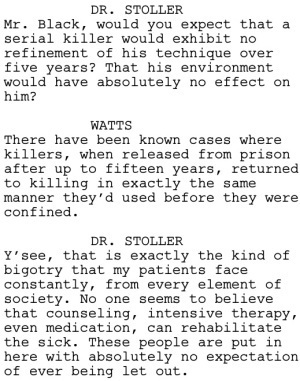

A forensic psychiatric hospital typically treats and/or seeks to rehabilitate those who have come into conflict with the law but who have been either considered unfit to stand trial or deemed not criminally responsible due to mental illness. Some such units might also house people convicted of crimes but who have been sent to such a facility for rehabilitation as opposed to prison, although it would seem, from Stoller’s early interactions with Frank and Peter, that this is not the case for East County:

The representation of the hospital is an interesting mix of apparent contradictions: on the one hand a forbidding, somewhat dilapidated building, whilst on the other staffed by a team who—on the surface at least—seek to maintain as relaxed and informal an atmosphere as is possible under the circumstances.

Black and Watts are led to the hospital in the wake of a brutal killing of a teenager who, in a scenario that makes for a thrilling teaser but hinges upon a ridiculous coincidence, is killed moments after relating a spooky story about the modus operandi of a killer housed at the hospital—colloquially termed “The Pest House” by some locals—in the exact same fashion. A sequence of murders follows, each of them apparently following the pattern of a different patient in the hospital, which leads their investigation a merry dance.

In the exchanges between Black, Watts and Dr. Stoller, the tension between those caring for the patients in such an institution versus those with a duty of care towards the wider public is drawn into focus. It is a perennial debate, and the script effectively and sensitively walks its fine line without ever coming down too firmly on one side or the other. In one such conversation, Dr. Stoller challenges Frank’s assumptions that one of her patients may have been able to replicate one of his crimes from several years previously:

The explanation for the run of apparent copycat killings is where the parallels with Perception‘s episode “Asylum” come to the fore. Whilst Purdue (), one of East County’s long-standing patients, is signalled throughout much of the episode to be the guilty party, it is in fact one of the staff, Edward (), who is responsible. His motives are hinted at in a conversation with Frank after Dr. Stoller narrowly escapes an attempt upon her life by an unknown assailant:

Again, I find it an uncomfortable resolution to such a story as this, in a desire to buck audience expectations about who the killer might be, to land upon a caregiver as the killer. Yet it is somehow the combination of Millennium‘s heightened sense of reality alongside a more restrained explanation for the killer’s motives that make its version altogether more successful than Perception‘s later plundering of a similar vein.

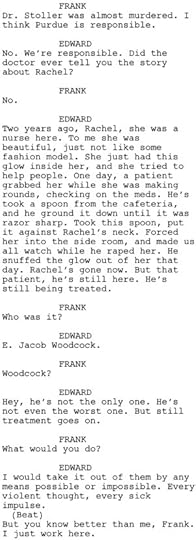

At the episode’s climax, Edward makes a more direct attempt on Dr. Stoller’s life at the hospital only for Purdue to intervene. Purdue brutally kills Edward before he can inflict any more harm, implying that the nurse has somehow taken his and others’ dreams out of their heads, leeching them of their darkest imaginings and inclinations in the process. Whilst other instalments of Millennium have memorably shown visions of demons when killers are advancing upon their prey, in this instance it is the very patients he has emulated that appear to Stoller as Edward advances towards her:

As one thread in my essay—”Evil Has Many Faces”—for the book Back to Frank Black, I wrote about the model of evil as a contagion, and its ability to take hold of any one of us as a result. Evil is, of course, a nebulous concept that defies any absolute definition, but perhaps something similar can be said of mental illness under certain circumstances. Edward was clearly affected by what he saw Rachel, his former colleague, endure. It is strongly implied that her mental health suffered in the wake of her attack, and perhaps the same can be said for Edward himself.

Millennium is, of course, often speculative in terms of how far it will push such concepts, but perhaps there is a metaphor here for the mental damage inflicted upon the victims of violent crimes and those whose spirit may be broken due to events or pressures in their own lives, including their highly-stressful attempts to care for others. It is a bleak message, but it may just hint at an emotional truth.

If you’re staying in this Halloween, you could do much worse that revisit “The Pest House” and consider its themes for yourself. But whatever you do, and as that Fox trailer warns, “Close your windows, lock your doors, and be very afraid of the dark”.

October 10, 2014

Perception “Asylum”

Title: Perception “Asylum“

Writers:

Director:

Network: TNT

Original Airdate: 9 July 2012

Today is World Mental Health Day. Since 1992, this day has been utilised by the World Federation for Mental Health to promote awareness, education and advocacy for mental health conditions and issues. This year’s theme is “Living with Schizophrenia“. Schizophrenia is a condition that affects an estimated 26 million people worldwide, but which is often sorely misunderstood and misrepresented. In addition to the WFMH’s report, the Rethink Mental Illness’s +20 campaign seeks to highlight how people with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses have a life expectancy of twenty years below that of average populations, and mainly so due to preventable physical illnesses unrelated to their diagnosis. The New Statesman this week published an affecting article on the same topic.

For my part, I thought it would be timely to revisit another series here on the blog for a second time, and one of which I was quite critical first time around: Perception. Second season instalment “Asylum” felt like a good candidate given that it features schizophrenia even more centrally than usual, and also as it gives some insight into how psychiatric hospitals are represented onscreen. And because—Perception being as it is—it features a guest turn from as the imagined presence of Sigmund Freud.

“Asylum” centres around the hook that Dr. Daniel Pierce () fakes symptoms of his schizophrenia in order to gain access to a psychiatric hospital. A stabbing has taken place there and patient Erica Beecher (), a young woman with obsessive-compulsive disorder, stands accused of homicide. Her lawyer, Dr. Reuben Bauer (), petitions Pierce for his help:

It’s clear from the set-up that Erica is innocent, so at least the cliche of the mentally ill as inherently violent is avoided. Setting aside how readily Pierce ensures he is picked up by the police and conveniently dropped off at the right hospital, I found the notion that anyone could fake their way into such a institution highly unlikely. Until, that is, I realised from an exchange in the episode that this has actually happened.

In 1973, psychologist David Rosenhan published a paper called “On being sane in insane places“. The paper is based upon a study now simply known as the Rosenhan Experiment, in which a number of “pseudopatients” successfully gained access to psychiatric hospitals by faking hallucinations, were promptly given diagnoses, and then subsequently refused permission to leave when they came clean about their intentions. In his conclusions, Rosenhan questioned the accuracy of psychiatric diagnoses, and also highlighted the dangers of dehumanisation and labelling in such institutions. Loosely, this is a theme upon which “Asylum” also touches.

Then there is the appearance of Dr. Sigmund Freud. Seventy-five years on from his death and in spite of much of his work now being challenged, it is clear that many of Freud’s ideas and much of his terminology have entered our lexicon—even though some of those ideas have arguably been lost in translation along the way.

Freud first appears to Pierce during a group therapy session, and pops up again throughout the episode as his imagined consultant, as befits one of the somewhat convenient elements of the Perception formula in terms of its representation of schizophrenia. It lends the script a few of its lighter moments—if obviously so—such as when the psychoanalyst offers Daniel Pierce some uninvited observations of his painting during an art therapy session:

Also up for consideration is “Asylum”‘s representation of the psychiatric hospital itself. At the outset, Pierce points us to the fact that this is a hospital with a poor reputation. Nevertheless, it feels somehow muted and sanitised, with patients mostly behaving either humorously or disturbed purely on cue as the script requires it. And then there is the episode’s big reveal—that a rumoured killer in the basement is very real, and that he is one of the staff.

This seems to be turning into a whole new cliche of the genre. Eager to avoid the error of painting sufferers of mental illness as violent criminals, any such audience expectations are undercut and the default is instead to have one of the caregivers be the big bad. I wouldn’t mind so much if this wasn’t becoming so commonplace. The clues are there from early on, but it still sits uneasily with me to paint health professionals in this light. The implication is that, given a position of power over someone so vulnerable, that power will be abused. There may be a grain of truth to this, but it doesn’t help when the reveal is a psychiatric nurse wielding a drill and yelling maniacal threats to lobotomise our hero. There’s no nuance here.

There are, however, some nice touches leading up to and during the instalment’s climax. It is through trusting the half-remembrances of a fellow schizophrenic in the hospital that Daniel is led to the killer. When subsequently kept prisoner in the basement, he realises—with a little gentle prodding from Dr. Freud—that he has been given LSD, and that what he sees as fire-breathing has in fact been brought about by synesthesia confusing and mixing his senses, thus leading him to identify the killer from his choice of chewing gum! And as for our letter opener-swallowing suspect, she is offered hope in the treatment of her OCD through the radical, non-invasive Gamma Knife surgical procedure. This stands in stark—and perhaps deliberate—contrast to the crude lobotomising methodology of the killer-of-the-week.

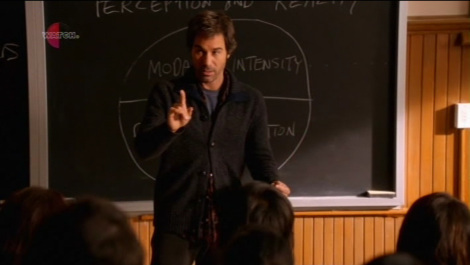

For all its flaws, then, Perception certainly laces episodes such as “Asylum” with fascinating psychological details, many of them authentic and educational. Another element that the series utilises particularly well is the monologue. Episodes are often bookended with these as Dr. Pierce addresses his students in the classroom on the topic-of-the-week. For some, these scenes may come across as stylistically heavy-handed, but for me—and I speak as someone who used to very much enjoy such voiceovers that were used to great effect in The X-Files (1993-2001) and Millennium (1996-99)—they work well as a framing mechanism. Perhaps the best way to sign off this post, then, is with Pierce’s closing thoughts to his students on dealing with mental illness, which posit a cautiously optimistic future for sufferers:

October 5, 2014

Homeland “The Vest”

Title: Homeland “The Vest”

Writers:

Director:

Network: Showtime (USA)

Original Airdate: 11 December 2011

Homeland (2011- ) returns to Showtime for its fourth season premiere tonight, and to UK screens via Channel 4 one week later. I thought it would therefore be timely to shine the spotlight once again on the series’ bipolar protagonist Carrie Mathison (). When I considered the series’ pilot episode for this blog I hinted that I would, at a later date, write about some of the third season’s developments that came in for criticism due to their representation of Carrie’s illness, but for now I would like to focus upon one of the series’ high watermarks: the penultimate instalment of Season One, “The Vest”.

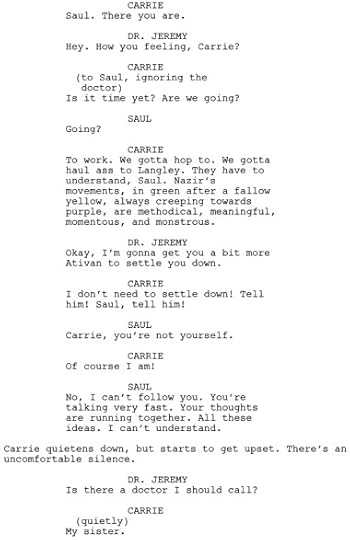

The episode follows in the wake of an operation that Carrie had been coordinating, but which went awry when a briefcase bomb was detonated in a public square. Carrie is in hospital having suffered a concussion, and in the throes of a full-blown manic episode. It is there that her Division Chief, Saul Berenson (), finds her desperate to return to work. Confused and shocked at her (ahem) frame of mind, Saul convinces her doctor—in spite of his initial protestations—that Carrie would allow him to be present whilst he consults with her:

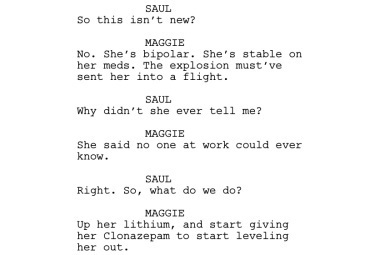

Back at Carrie’s place, her sister Maggie () arrives, and Saul finally learns the truth about Carrie’s condition—a truth she has, to this point, successfully hidden from the CIA for her entire career:

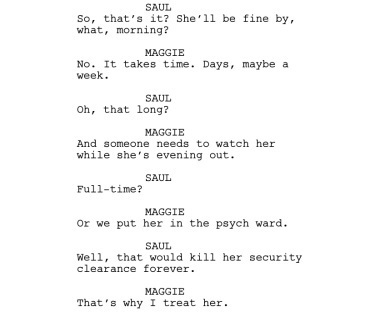

Carrie reluctantly takes the medication that her sister prescribes, but still continues to trawl through the case notes she has brought home, feverishly highlighting passages with different coloured markers. Saul is out of his depth, and impatient to have Carrie back to “normal” given that a terrorist attack related to her operation is expected imminently:

The interaction between Carrie and her sister is strained at best, and this is not helped when Carrie jumps out of her car and runs across a street—nearly getting run over in the process—in order to inspect an area of fenced-off, fallow ground. The moment somewhat obliquely provides Carrie with a breakthrough about the information she has been analysing on terrorist Abu Nazir’s activity, demonstrating that she is still high-functioning throughout her ongoing manic episode. Maggie, however, insists she takes a sedative given her dangerous behaviour.

Whilst Carrie is resting overnight, Saul pieces together her evidence on her living room wall, realising that it is a chart of Nazir’s timeline, colour-coded to describe changes in his behaviour and seeking to infer from these his state of mind. When she comes downstairs the following morning, Carrie is overwhelmed to find that Saul now finally understands her train of thought. As Danes describes this scene, “Saul is able to organise that brilliant chaos, and that wall I think represents their friendship and their camaraderie and their incredible efficiency and brilliance in working together professionally”.

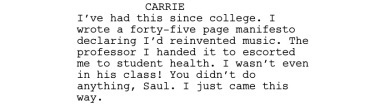

Carrie also takes a moment to reassure her mentor that he is not to blame for her condition, having overheard him discussing how she was “damaged” after an operation that went awry in Iraq, and for which he takes responsibility. It’s a moment that effectively shows Carrie’s perspective upon her illness as inherent as opposed to triggered by any particularly stressful event in her chosen profession:

Throughout “The Vest”, the audience is treated to an untimely but understandable manic episode that feels utterly authentic. What interests me in particular regarding Carrie Mathison, though, is how the character came to be defined the way she is at all, and how the creative teams behind Homeland collaborated in this regard. The documentary included on the Season One box set, “Under Surveillance“, offers a number of insights and demonstrates how Carrie’s condition was incorporated into the the themes at the heart of the series.

Series creators and executive producers Howard Gordon and Alex Gansa developed the concept from Israeli writer ‘s series Hatufim (renamed Prisoners of War for international audiences). Carrie Mathison’s character had no equivalent in Hatufim, and moreover her illness was only added at a relatively late stage in the character’s development, once the series was destined for Showtime, who asked for her to be made “more of a cable character”, i.e. more complex, more flawed. Gansa further reveals, “Carrie was a direct response to Jack Bauer. In the mindset of, ‘We don’t want to do 24 again. How do we not do 24 but make it about the intelligence community anyway?'”

“We wanted to create a hero who on one hand was doing many of the same things that Jack was doing, but couldn’t be more different,” Gordon explains further. “Someone who, rather than being institutionally acknowledged as this great hero, was someone who had been marginalised. And we were looking for ways to dimensionalise Carrie and maybe explain some of Carrie’s obsessive behaviour, some of Carrie’s out-of-the-box thinking.” Gansa concludes, “Ultimately we settled on the bipolar illness because it turned her into somebody that had a pathology that was unreliable, and that was very interesting to us as storytellers. ” Clearly Carrie’s condition adds to what Gansa describes as the “grey, ambiguous space” that Homeland inhabits.

Much of the palpable success of Carrie Mathison can be ascribed to Claire Danes’ Emmy and Golden Globe-winning performance—the former specifically awarded for her powerhouse performance in “The Vest”. Alex Gansa reveals, “Howard and I had Claire in mind from the get-go. Literally, the minute we talked about this person being a woman, and we knew roughly what age.” He goes on to reveal how that choice of age was selected to offer hope that Carrie could still manage her bipolar. “We wanted her in her early thirties because we wanted her to be at a place in her life where she was an experienced enough intelligence officer, but also young enough so that there was a possibility that she could defeat her disease and really integrate into life in a full way.” (The choice of word “defeat” is unfortunate and perhaps speaks to an underestimation of the condition, which in reality can at best only ever be managed.)

Howard Gordon describes Homeland as a “writer staff-driven show”, and Meredith Stiehm was the member of the writers’ room who was most drawn towards Carrie Mathison as a character, and who champions her. In terms of what she sought to represent through the character, Stiehm offers a more realistic yet still optimistic perspective:

“I wanted to show that you can have illnesses—physical or mental—and cope with them, and you can function with this pretty extreme disorder… Carrie is somebody who is excellent at her job, and she loves her job, and she has this illness. And she has to keep it a secret, which leads to poor treatment of the illness, and poor maintenance… [But] there’s sort of an order that she perceives that nobody else does, so what we might experience as scattered and crazy, she is seeing as lucid.”

As a cliffhanger leading into a season finale, “The Vest” ends in suitably dramatic style. Carrie makes the mistake of calling Brody () to invite him over even as—unbeknownst to her—he is preparing the very attack she is trying to stop, using the titular vest. Brody tips off CIA Deputy Director David Estes (), who arrives unannounced at Carrie’s home to call her to account. He immediately moves to have the evidence that Carrie has illegally brought home removed, ignoring her extreme protestations, and sets the wheels in motion to have her fired.

Director Clark Johnson had Claire Danes improvise the episode’s final moments, which rawly portray both her condition and her fury at being removed from service just as she has made a pivotal breakthrough. Danes viewed YouTube videos that people had posted whilst in manic states to help her with such aspects of her role, often watching them between takes. The actress says of the final scene, “It was supposed to end where I say to Estes, ‘I’m about to solve this fucking thing,’ and it was supposed to fade to black. And Clark said, ‘I’m just gonna let you go. You just go.’ I said, ‘What do you mean, I just go?’ He said, ‘Y’know, we’ll see what happens.’ I said, ‘Stop this. Enough already. Stop pushing me.’ But he said, ‘I know you’re full of resentment right now, but you’re in the right place for this.’ It was thrilling, it was exciting, but it was a lot. They didn’t let me drive myself home that night.”

Going into the season finale, there is a stark sense of realism to the way in which Carrie Mathison loses everything as a result of her behaviour. This feels authentic for a person in her position, struggling to manage her bipolar disorder whilst holding down such a stressful job. What Homeland was to find most difficult was where to take the character next. It is here that it was to falter, seeking to rebuild her status within the CIA in order for the series’ format to be preserved. That, however, remains a topic for future posts. And as to where Season Four will take her next—both physically and emotionally—we’re about to find out.

September 1, 2014

The X-Files “Elegy”

Title: The X-Files “Elegy“

Writers:

Director:

Network: Fox

Original Airdate: 4 May 1997

It was inevitable that this blog would, sooner or later, embrace The X-Files (1993-2002). It is amongst my strongest creative influences, the project that led to me setting up this blog certainly owes a lot to ‘s seminal series, and the links between mental health issues and experiences of and attitudes towards supposed paranormal phenomena have their own emerging field: anomalistic psychology.

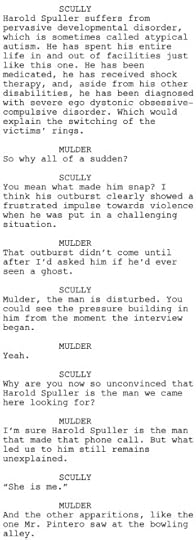

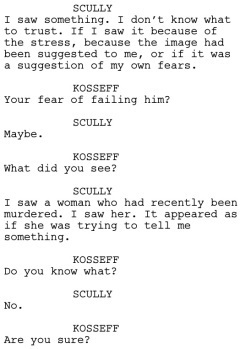

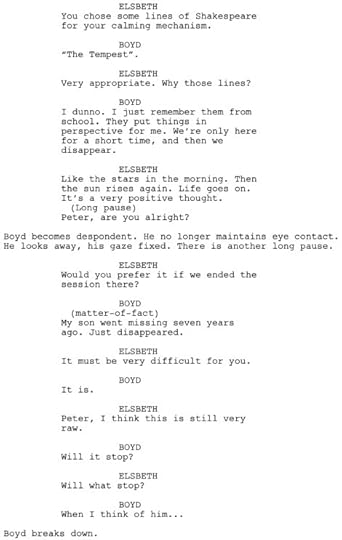

“Elegy” takes places towards the end of The X-Files‘ fourth season, a year rich in the series’ mythology that finds Special Agent Dana Scully (Gillian Anderson) battling cancer as a likely consequence of procedures inflicted upon her during her earlier abduction. Whilst her own state of mind features significantly during the episode, the investigation-of-the-week centres around Harold Spuller (), a sufferer of a form of pervasive development disorder, a complex diagnosis that sits on the autism spectrum.

Special Agents Fox Mulder () and Dana Scully are called in to investigate a series of murders, given that the owner of a bowling alley where Spuller works had a ghostly vision of the latest victim inside the pinsetter machinery at the time of her death across the street. The words “She is me” are revealed by means of forensics to have been invisibly inscribed into the waxy coating on the bowling alley lane flooring.

A 911 phone call was also received shortly before the killing, which is traced to a psychiatric facility where Spuller resides. When Scully spots something of significance in a crime scene photograph—the victim’s wedding ring switched from one hand to the other—she posits a theoretical diagnosis of ego dystonia when Mulder seeks her insight into the potential psychology behind such behaviour.

Scully accurately explains that this is a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder wherein a person has “persistent and inescapable impulses to change things, to organize, to reorganize” even whilst being aware that such behaviour is unreasonable, before going on to clarify that the condition is “not ordinarily something that escalates to a murderous impulse.” It’s an odd moment in that, whilst it preserves the dynamic between the duo—Scully offering a tenuous science-based explanation before Mulder starts exploring his own out-there theories, of apparitions as death omens in this instance—it stands out as somewhat anomalous that Mulder, the skilled profiler and gifted psychology graduate, should seek Scully’s advice on this aspect of the investigation. As such it does neither character justice, and offers a leap of logic in spite of Scully’s caveat.

The pair are permitted to talk to Spuller at the facility, and he becomes extremely agitated during their questioning. Whilst this hardens Scully’s position as regards his potential guilt, Mulder is—to his credit if, naturally, for unconventional reasons—altogether less certain:

Mental health and the paranormal can be a quite natural fit, as is inferred by the field of anomalistic psychology, but they can also make for uncomfortable bedfellows. On the one hand, there is the tendency to ascribe some “magical” ability to mental health sufferers, whilst on the other there is the potential to write off claims of paranormal experiences in a derisory fashion, as the preserve of the insane. It’s a fine line to walk, and “Elegy” isn’t always successful in navigating it.

Spuller makes for a partly sympathetic character, through his sensitive, empathic nature, but also when we see the heavy-handed treatment he receives at the hands of the local police that are quick to assume his guilt. We see, too, how Spuller obsesses over how he replaces bowling shoes in their racks after use, and, later, visit a secret room at the rear of the bowling alley where he posts up score sheets that he has memorised in their entirety, reciting them whenever a player’s name is mentioned. Yet it is also inferred that he has a somewhat creepy obsession with some of the girls that visited the alley, secretly keeping photos of them in his room. Whilst such revelations lend a sense of mystery in preserving suspicion upon him, they conform to the stereotype of the mentally ill as either imbued with special abilities or creepy and untrustworthy. Or, as here, both.

It is worth noting that Shiban’s screenplay was in part inspired by One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), a film most cited by those asked to cite a depiction of the mentally ill acting strangely or violently, although here Spuller is later revealed to be innocent and, ultimately, victimised. And the episode has also suffered some strong criticism for its representation of mental illness.

None of this is to criticise Porter’s portrayal of Spuller, who superbly represents some of the outward aspects of pervasive developmental disorder in his social awkwardness and body movements. Invited to audition for the role by former college friend and series producer , companion chronicle of the series “I Want to Believe: The Official Guide to The X-Files” (Andy Meisler, 1998) tells of just how he came to inhabit the role:

Many of the gestures and tics Porter used in the episode were products of his research, in several mental hospitals and adult group homes, for [an original play he had appeared in previously called] “Asylum”. In fact, he says, a certain flapping-hand movement became so vital to his portrayal of Harold that he kept doing it even when looping some dialogue in the recording studio after filming had wrapped.

It is noteworthy, too, that today Spuller’s “atypical autism” diagnosis would most likely be termed pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), following the reclassification of disorders on the autism spectrum in the latest edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders”. The complexity and changing nature of these definitions speak to the uncomfortable reality of how little we truly understand such conditions.

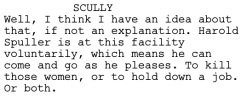

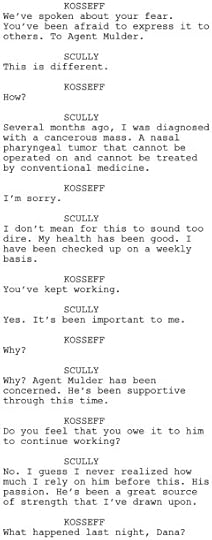

On a more positive note, the mythology and character-led subplot of the episode offers its most affecting scenes. After Scully witnesses her own ghostly apparition of an impending victim and the words “She is me” appear to her from nowhere on a restroom mirror in blood, she visits her counsellor, Agent Karen Kosseff () to discuss her state of mind. Anderson’s Emmy Award-winning performance sells her predicament utterly throughout both this episode and the entire season, including in this scene:

Sadly, the weakest element of “Elegy” is its clumsy denouement. From nowhere, it is revealed that the killer is in fact Nurse Innes (), a mental health professional in a position of care over Spuller, who verbally and physically abuses her patient, and is in the habit of denying him his medication and consuming it herself. This is utterly bizarre, not least in its suggestion that the potential side effects of the drugs clonazepam and clozapine might act to induce a campaign of serial murders, thus forming part of her motive in the killings alongside her own severe emotional pain. Furthermore, the character of Innes has done little throughout the episode to this point save stand awkwardly in the background during Spuller’s initial questioning by Mulder and Scully.

It is true that the potential side effects of clonazepam can, in rare cases, be to induce aggressive behaviour or even a shift in personality, and so perhaps a case could be argued that Shiban’s script is seeking to make some comment on the dangers inherent to such powerful medication. Given how briefly the topic is covered, though, this rushed conclusion to the investigation does neither the mental health care profession nor pharmacology any favours, even within a fictional context that seeks to explore the realms of extreme possibility.

The more successful emotional through-line of the episode is summed up in a final exchange between Mulder and Scully, in which Mulder delves deeper into this theory over death omens that unwittingly disturbs Scully yet further:

Mulder’s willingness to pose such a seemingly unlikely explanation of course speaks to his own complex psychological history, scarred by the as yet unexplained abduction of his sister when he was a child. It would seem that he is right, however, as Spuller dies soon afterwards from respiratory failure, and a tearful Scully has a final vision of him when she sits alone and forlorn at the wheel of her car in the episode’s final moments. Her continuing mental battles over her life-threatening illness bring the instalment to a shattering conclusion.

“Elegy” is at times very clumsy in its handling of mental illness and its periphery, and yet the gloss of so many aspects of its production—foremost the performances of its leads—goes some way towards rescuing the episode from its failings. The phenomenon that was The X-Files touched upon anomalistic psychology repeatedly throughout its remarkable run, and that alone means this blog will return to its rich canon in the very near future.

August 18, 2014

Waking the Dead “Anger Management”

Title: Waking the Dead “Anger Management”

Writers:

Director:

Network: BBC

Original Airdate: 1 & 2 August 2004

Waking the Dead (2001 – 11) was a BBC One police procedural drama series featuring the harrowing work of a CID Cold Case unit. Significantly, whilst focussing for the most part upon the story-of-the-week, its core cast was sharply characterised, and none moreso than its leader, Detective Superintendent Peter Boyd (). In the hands of such an accomplished actor as Eve, Boyd became a unique creation, not always likeable but undeniably authentic. As , a director of some of Waking the Dead‘s later episodes, once remarked, “Boyd is a role he created”.

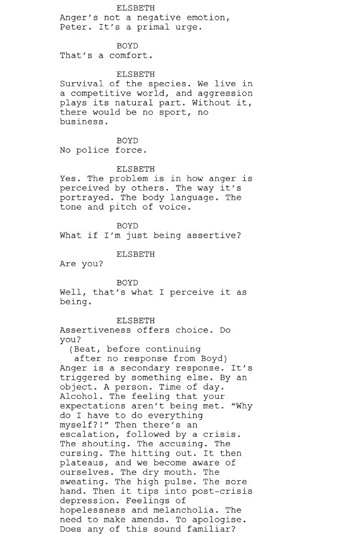

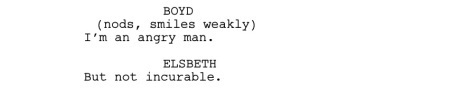

Arguably, it is through Eve’s work in defining the character of DSI Boyd that the story “Anger Management” (presented over two hour-long instalments as per the series’ regular format) comes to delve into his inner life. Given Boyd’s volatile mood—as frequently endured by his long-suffering team and suspects alike—his visits to a therapist that intersperse the evolving narrative of the investigation feel not just a natural evolution of the character but perhaps even overdue by this midpoint of the series’ fourth year.

Anger and our need to keep it under control, is a theme underscoring the episode: in terms of the motive for one or more of the crimes under the microscope, in terms of the personal struggles of some of the key characters on both sides of the investigation, and in terms of the dynamics that, unchecked, it can create.

An apparent suicide in a halfway house takes a more sinister turn when the gun used is linked to two unsolved murders from prior decades and, on further investigation, a number of contract killings. One of the suspects, Sam Jacobs (), has recently left prison after serving a sentence for grievous bodily harm against a neighbour, committed in a pique of jealous rage after the man sexually assaulted his wife. Another, Don Keech (), battles to retain self-control in moments of high stress.

Whilst Boyd’s investigative team and the audience have become used to the Superintendent’s fits of temper, they and we alike are unsettled by quite how good-humoured he is in his first appearances in the story. The reasons for this soon become clear, though, as an odd visual motif of sweeping clouds is used to transition into a number of scenes that offer insight into his therapy sessions to explore his anger issues more deeply.

Therapy—be this counselling or true psychotherapy—is the most common type of talking treatment recommended for those with anger issues severe enough to warrant intervention. Boyd’s sessions seem to take the form of counselling given their focus on the here and now, although they ultimately veer into territory potentially more appropriate to a psychotherapeutic approach.

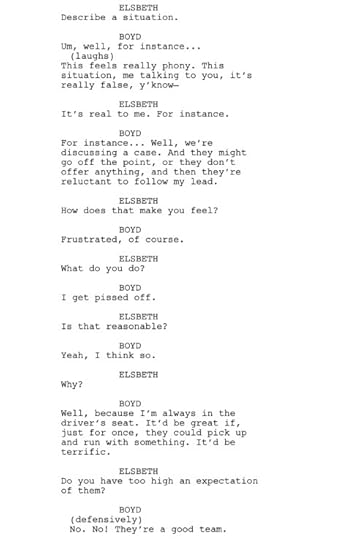

The representation of these sessions takes care to show the passage of time, with different segments clearly taking place in different sessions over an extended period (similar to the timeline of the investigation itself), as indicated by changes in the time of day, or in Boyd and his counsellor Elsbeth Varley’s (Kerry Fox) outfits. Early sessions find Boyd somewhat cynical and combative to the process itself, quite in keeping with his character and not untypical of the slow building of trust and rapport between patient and therapist. Thereafter, however, the conversations become more constructive, and in one exchange Elsbeth provides Boyd (and the audience) with a good introduction to both the nature and role of anger, in terms that are all too familiar to the detective:

Boyd uses what he has learned to get the better of Keech during the suspect’s cross-examination, exploiting the man’s own anger management techniques to draw information from him. As the investigation evolves further, though, the DSI’s mask slips. The gun central to the investigation is stolen from a safe in the team’s base of operations, and Boyd turns his wrath on the security detail for allowing such a crucial security breach to occur. Subsequently, his forensic scientist Dr. Frankie Wharton () receives similar treatment when it becomes she has been less than forthcoming over the circumstances of the theft to preserve her pride. And the toxic and contagious nature of the dynamic Boyd has fostered in his team becomes apparent when his stressed-out Detective Inspector, Spencer “Spence” Jordan (), adopts similar raging behaviour in order to get results.

Boyd uses what he has learned to get the better of Keech during the suspect’s cross-examination, exploiting the man’s own anger management techniques to draw information from him. As the investigation evolves further, though, the DSI’s mask slips. The gun central to the investigation is stolen from a safe in the team’s base of operations, and Boyd turns his wrath on the security detail for allowing such a crucial security breach to occur. Subsequently, his forensic scientist Dr. Frankie Wharton () receives similar treatment when it becomes she has been less than forthcoming over the circumstances of the theft to preserve her pride. And the toxic and contagious nature of the dynamic Boyd has fostered in his team becomes apparent when his stressed-out Detective Inspector, Spencer “Spence” Jordan (), adopts similar raging behaviour in order to get results.

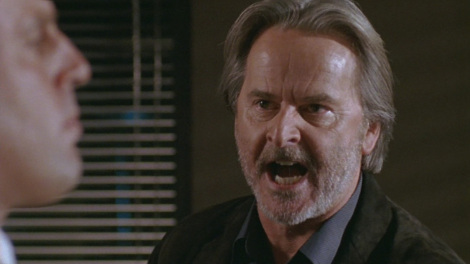

There are moments of black humour too, though, such as when Boyd retreats to his office and starts reciting lines from “The Tempest” to himself as a calming mechanism only to be interrupted by the comparatively soft figure of his confidant and psychological profiler Dr. Grace Foley (). Even as she seeks to check how he is in the wake of one angry outburst, he repels her concern by citing his counsellor’s terminology: “Not now, Grace. I’m having a post-crisis depression.”

Waking the Dead very much capitalises upon the audience’s familiarity with the dynamic between Boyd and the rest of his team. Their scenes together are played very naturalistically, which is testament to the fine ensemble performance of all the series’ leads. So, when Elsbeth challenges Boyd to give an example of a work situation that makes him angry we could probably give her a long list, even whilst Boyd is initially reticent to share one of his own in a scene that is intercut with fractious moments of the investigative team trying—and singularly failing—to collaborate as a unit:

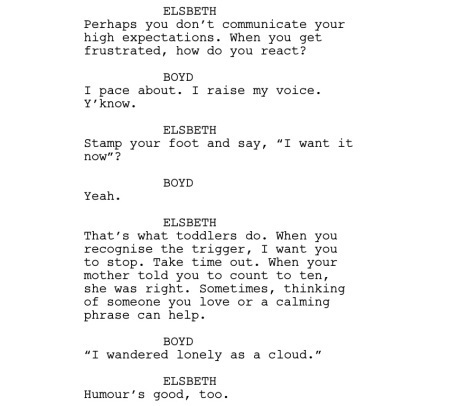

There is an authenticity, too, in how Boyd only arrives at his personal truth after any number of sessions with his therapist. The dialogue, its delivery, and the direction in this scene—one punctuated by lengthy silences—are all superlative as he is prompted into his revelation through consideration of the nature of the very calming mechanism he has selected. Boyd’s choice of text is more telling than perhaps even he first recognised:

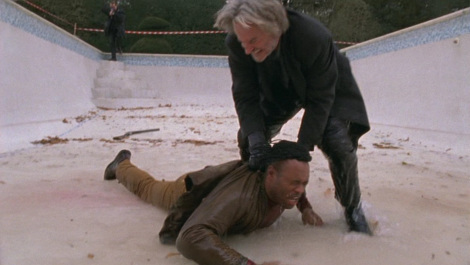

The scenes between Boyd and Elsbeth all take place in the story’s first instalment, whilst the second sees the investigation reach its climax and therefore is much more procedural in nature. The themes established through his therapy sessions continue to play out, though, and indeed Boyd still gets to vent his “righteous” anger at appropriate moments whilst, crucially, keeping his cool at others. When he finally comes face-to-face with the killer, Boyd takes a punch to the face that leaves him stunned for a good few minutes, but is ultimately able to manipulate the situation to get the better of his opponent, now himself wounded and trapped in a disused swimming pool. Having disarmed the man, though, Boyd’s emotions get the better of him and he half-drowns his cornered quarry before armed backup arrives and brings the situation under control.

Anger has its time and place, the story tells us. Yet it can also be poisonous and counter-productive, and we must recognise and address it when it becomes a serious problem. Boyd’s own anger stems from a heartbreaking trauma that defines both his character’s motivation and behaviour. This episode makes explicit the link between his demons—little referenced in the series at this point—and their outward manifestation. Detective Superintendent Peter Boyd is a character we root for, in spite of—and perhaps even because of—his flaws as a human being.

If I had a criticism it is that the series too quickly sets aside the personal epiphany that Boyd has in “Anger Management”, eschewing any long-term character development and instead maintaining the established dynamic of the team. By the next episode, he is back to his brooding and often seething self, and any sense of continuity is lost. Then again, he has more trauma in store in future episodes—the death in service of members of his team, and, ultimately, a tragic conclusion to the story of his missing son in Series Seven (a tale for another day)—and perhaps a character shift wouldn’t ring true either, a pat resolution to a deep-seated trauma. Ultimately, Waking the Dead stands the test of time as an often exceptional creative collaboration that bears all the hallmarks of authentic and engaging drama.

Waking the Dead Series Four is available on DVD in both Region 1 and Region 2 formats.

July 27, 2014

Whitechapel Series 2 Part 2

Title: Whitechapel Series 2 Part 2

Writers:

Director:

Network: ITV

Original Airdate: 11 October 2010

Whitechapel (2009-13) is a series that chimes with some of my key interests, comprising as it does a speculative crime drama with a flawed lead character who struggles with a mental health condition. Sadly, it was cancelled last year after a fourth series that heightened its supernatural element via a run of stories peppered with horrific visions and unsettling implications that its characters and their East London location were embroiled in a longstanding battle between good and evil. As such, it is yet another series to portray shades of Millennium (1996-99).

Back in its second series, the show followed its first year’s impactful tale of a modern day Jack the Ripper with a storyline featuring a slew of murderous crimes that appeared to indicate that the Kray twins were posthumously terrorising London’s streets. Rooted a little less in the fantastical, the series instead immersed itself in the very real dangers of the gangland underworld.

Aside from its hook in featuring updated versions and reflections of such infamous criminals, Whitechapel‘s choice of protagonist is interesting and unexpected. Detective Inspector Joseph Chandler () is an unlikely choice to lead his district: a fastidious, privileged and well-connected character quite at odds with the working-class detectives under his command, and notable his Detective Sergeant, Ray Miles (). Much of the black humour that threads its way through the series comes from their relationship as it slowly evolves from contempt towards one of mutual respect, and Penry-Jones and Davis are superbly cast and as excellent as always in its portrayal. Early in this second part of a three-part story, as it becomes evident that direct descendants of the original Krays are responsible for a spree of horrific murders, they have a brief exchange that both references how this case has gotten under the skin of the hardened detective sergeant and also typifies the banter that the two characters enjoy with one another:

The fact that this development in the case leads to the involvement of the Organised Crime Division—a real institution—allows for a neat pun of acronyms that makes its way onscreen, given that DI Chandler also suffers with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

OCD is a condition to which many people feel they can relate, given how common minor obsessions and compulsions can be in our daily routines. But for sufferers of OCD these obsessions are so strong, and the accompanying compulsions intricate and repetitive to such a degree that they severely disrupt the sufferer’s day-to-day life. Obsessive thought processes lead to anxiety, which in turn leads to compulsive behaviours that offer some temporary relief from those anxieties. But then the thoughts and anxiety return, and so the cycle continues.

DI Chandler clearly maintains an extremely stressful job, and therefore is not an acute OCD sufferer. The audience is, however, privy on a number of occasions to his obsession over personal cleanliness, and he is often to be seen rubbing his temples in an attempt to calm his anxiety. In this episode, he is also extremely defensive when DS Miles comes into his office to find him separating his drawing pins by colour and counting them obsessively:

This dialogue is authentic in as much as Chandler frames his behaviour as being “a bit OCD”, in the way that many people do about their own minor behavioural compulsions. But is this helpful? In one sense, OCD is a condition that people can often recognise hints of in themselves—even if only privately so—and perhaps that helps to normalise the condition. Indeed, a diagnosis will usually be subcategorised as anything from mild through moderate to severe. Yet, on the other hand, perhaps that very normalisation also serves to understate how crippling it can be at the far end of the scale, and glosses over the serious nature of some of its potential causes: abuse, trauma, depression or some other biological factor. Nevertheless, I don’t balk at people describing themselves as “a bit OCD”—as I am sure I have done myself on occasion—as much as I would at someone claiming to be “a bit bipolar”, for example. That’s in a whole other league.

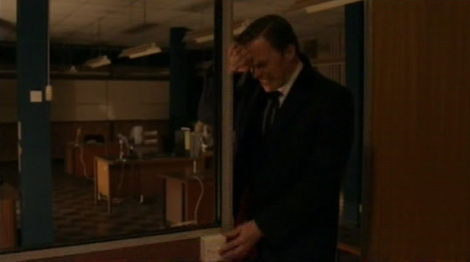

DI Chandler’s OCD is, however, more than just a character quirk. There is a suggestion that it informs his eye for detail in the course of his job, but this is never overplayed and the condition is never put forward as granting him a special ability. (If a comparison to Monk (2002-09) suggests itself at this juncture, then this is something I will explore on this blog at a future date.) And significantly, towards the episode’s climax, it plays a crucial—and potentially catastrophic—role in a sequence where the Detective Inspector has set up a meeting with one of the Kray twins at an East End pub. His anxiety levels extremely high given the violent threats these all-new Kray twins have already made towards him, and trying desperately to leave his office, he pauses to switch the lights on and off several times. He then takes a few steps away from his office before being compelled to return, and repeating the process. Furious at himself for being locked into this compulsive cycle, he finally summons the mental strength to smash the light fixture so he can go on his way.

It is an arresting moment that serves to heighten the dramatic tension yet further, and seems apt in terms of the level of stress that DI Chandler is under at the time. The scene’s resolution doesn’t quite ring true, but nevertheless it is a memorable example of a mental health condition being conveyed dramatically with losing sight of a measure of authenticity.

Given its strengths, it pains me a little to have to write about Whitechapel in the past tense, and I can’t help but feel that the television landscape is a little poorer for its cancellation. If given at times to fanciful and illogical leaps in plot, it was an always bold series on the brink of revealing its master plan, and also offered a painfully honest representation of a condition that is often misunderstood and underestimated. For those in the UK, do yourselves a favour and check it out on DVD or via re-runs on ITV Encore, or alternatively watch it on Amazon Prime in either the UK or the US.

June 26, 2014

Nashville “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad”

Title: Nashville “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad“

Writers:

Director:

Network: ABC

Original Airdate: 30 April 2014

I often describe Nashville (2012- ) as a guilty pleasure. Created by , it tells the stories of a handful of singers, songwriters and musicians in “Music City”, from seasoned professionals at the height of their powers to up-and-coming artists trying to break into the scene. In the great country tradition, their personal lives are car crashes (a metaphor rent none-too-subtly literal in the show’s first season finale, “I’ll Never Get Out of this World Alive“). Yet in a series often given to fast-moving, improbable and exaggerated plot developments, what emerges from “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad”—a recent episode set in the lead-up to the Season Two finale—is a surprisingly sensitive and nuanced depiction of a very public mental breakdown and the beginnings of a recovery.

Scarlett O’Connor () is a gifted poet and musician, the niece of country royalty in Deacon Claybourne (), a troubled soul who also has a complex history with her mentor, Rayna James (). Rayna is the well-established “Queen of Country” and has recently set up her own label, Highway 65, as a way both of retaining control over her own career and nurturing new artists. Signing Scarlett as her first artist, she has used her considerable influence to secure her protege a huge opportunity with the supporting slot on her most recent signing, country crossover star Juliette Barnes‘ () latest tour.

Yet for Scarlett, things are moving too fast. She never craved the limelight, but has gone along with decisions that have thrust her firmly into its glow. During recording sessions for her debut album, she has developed a reliance upon “uppers” as a consequence of a casual suggestion from her hot-shot producer. She is a delicate soul under intense pressure. Tellingly, a trigger point arrives in the form of an unexpected visit from her controlling and overbearing mother, Beverly O’Connor (). One night on the tour, finding it all too much and, having pleaded unsuccessfully with Juliette for a night off, Scarlett downs a couple of large whiskies before taking to the stage, where she very quickly has a very public breakdown.

Nashville is, to a large extent, pure soap melodrama. But there is also an extra dimension at play, and I would venture that this emanates in large part from the series’ unique and celebrated soundtrack. Curated by respected producer T Bone Burnett and singer/songwriter Buddy Miller, it has highlighted the very best—and, often, the most overlooked or underrated—talent from the Nashville and Americana music scenes, showcasing thoughtful songs to a primetime audience. These songs are carefully selected to fit both storyline and theme and, as such, provide insight by becoming a character’s inner monologue or narrating a potted back story. Accordingly, Scarlett’s complex if not downright poisonous relationship with her mother was established in the previous episode, “Crazy“, when she acerbically dedicated a rehearsal performance of her composition “Black Roses” (actually written specifically for the series by songwriter Lucy Schwartz) to Beverly. Her mother could only stand by and listen, embarrassed and insensed.

On stage, Scarlett suffers a psychotic episode. Her visions blurs, then she begins railing against an invisible enemy—clearly her bullying mother—before crawling under a stage piano and clinging onto it for dear life. She is unceremoniously escorted from the stage, sedated by a personal physician, then whisked via Juliette’s private jet to a top-notch hospital. When she wakes, she is horrified to find herself secured to the bed, and her mother in attendance. She freaks out, escapes (somehow) her bonds, and flees the hospital. Her mother gives chase, yelling after her in her own, counter-productively neurotic way, but it is Rayna’s contrasting, calming influence that is able to reason with Scarlett:

The causes of psychosis are varied. In Scarlett’s case, there are a number of factors seemingly at play. Anxiety is certainly one, both in terms of her unhappiness at the direction her career is taking, and due to the sudden appearance of her mother. Trauma or abuse at her mother’s hands is heavily implied to be another, as is a hereditary component. To the writers’ credit, Beverly is illustrative of most of the characters in Nashville in that she is neither all good nor all bad. She has clearly suffered at the hands of her own abusive father, and is careful to advise Scarlett’s doctor that both her and her grandmother have suffered psychotic episodes. Her constant arguments with her brother Deacon, who is also an alcoholic and cautions Scarlett over a genetic proneness to addiction, also go some way to hinting at the difficult upbringing they both endured. There are potentially both biological and social factors that can lead to cycles of such mental illness being perpetuated through the generations, and it is pleasing to see that toxic but not uncommon mix acknowledged here.

Scarlett heeds Rayna’s request and reluctantly returns to the hospital to continue her treatment. Here, a number of friends and family rally one-by-one at Scarlett’s bedside, including her estranged best friend, Zoey Dalton (). It is with Zoey that Scarlett feels able to discuss the uncomfortable truth that her memory of the incident onstage differs significantly from the truth. Initially describing it as a mere “hiccup”, she is forced to acknowledge the true extent of the episode when she catches up with footage that appears online:

This scene highlights a disturbing aspect of psychosis and other mental illnesses, that of not being able to trust your own thoughts or memories. What the episode skips over is the follow-up treatment or diagnosis that Scarlett receives; psychosis itself is not a diagnosis, but rather a symptom of some other underlying problem. It remains to be seen whether or not the series will revisit this topic as part of Scarlett’s ongoing arc, but here the details are lost to Nashville‘s relentless pace of storytelling.

What is handled sensitively, however, is the impact upon her career. For anyone suffering a permanent mental illness, the long-term impact upon their working life can be severe. Scarlett benefits where many do not, from having access to the very best health services and also an understanding boss. Rayna ignores the cynical voices that tell her that this kind of “tabloid tragedy” is what makes a country song, and that she should seek to capitalise upon it. It is something the gutter press would do well to learn, as would the readers who lap up every celebrity’s fall from grace when their vulnerabilities are made public. Instead, once Scarlett is well enough to have another conversation Rayna, herself a mother and very much a maternal figure in the show, puts her artist foremost above her own interests or those of her ailing record label:

It is a tender scene, and the heart of the episode as Scarlett finally starts to assert what will make her well. She follows this up by confronting her mother, who is desperate for her to remain in hospital and undergo further treatment, and telling her that the very best thing she can do for her daughter right now is to go back home and give her some space. It is odd, in the context of both the episode and the ongoing series, that Scarlett is suddenly able to find her inner strength and to acknowledge the string of bad decisions she has made and that have gotten her to this crucial crossroads in her life. Her dialogue also acknowledges that extended treatment served her mother’s wellbeing, such that the show takes care not to advocate refusal of treatment. What it does do effectively, however, is to highlight that each individual has different needs, and that these needs should be understood and respected.

It is worth noting that all of Nashville‘s episode names are borrowed from song titles; “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad” is the title track of Tammy Wynette‘s first album. Whilst Scarlett appears not to have suffered a powerful addiction, Wynette had a long-term problem with painkillers, and was treated at the Betty Ford Center at around the same time she joined the cast of soap opera Capitol (1982-87), in which she played a hair stylist turned singer. Art imitates life imitates art.

Compared to a series such as Perception, in which Dr. Pierce’s mental health is often little more than a plot device, in Nashville the personal and inner lives of the characters are key to the heart of the drama and, naturally, the music. The sense of authenticity and gravitas that flows from this focus are to Nashville‘s credit. Over this instalment’s final scene, Rayna James performs the song “Wrong for the Right Reasons” (by Chris DeStefano, Rosi Golan, and Natalie Hemby), which neatly frames Scarlet’s arc and the wider themes of the episode. Some good can arise from times of crisis, it teaches us, if we let ourselves take the right lessons from our more painful experiences.

In the words of Henry Giles, “Music is the medicine of an afflicted mind”. Given both its superlative soundtrack and episodes such as this one, maybe I should stop referring to Nashville as a guilty pleasure after all.

“Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad” is currently available to watch online via ABC in the USA and 4od in the UK.

June 1, 2014

Perception “Pilot”

Title: Perception “Pilot“

Writers:

Director:

Network: TNT

Original Airdate: 9 July 2012

On the basis of its first instalment, Perception (2012 – ) fits with a trend of television series to primarily portray mental illness as the key to some rare investigative talent. Whilst it is encouraging to see a schizophrenic portrayed as the protagonist as opposed to some crazed killer, the tone set by this show’s pilot episode is broad, and it misinforms the viewer at almost every turn.

Perception focuses upon Dr. Daniel Pierce (), a college professor in neuroscience and occasional consultant to the FBI at the request of former student now Agent Kate Moretti (). Pierce also suffers from schizophrenia, and is shown to suffer from hallucinations and paranoid delusions. In the context of campus life, though, and with the support of university dean Paul Haley () and teaching assistant Max Lewicki (), his behaviours see him accepted as little more than an eccentric academic.

In the first of the rather on-the-nose presentations to his classes that book-end the episode and make up part of the formula, Dr. Pierce outlines one of the core challenges to his character presented by his illness—namely to recognise what is real, and what is not:

Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder on which views and understanding have shifted over time, both informing and informed by debate and research. Key to its symptoms, though, lies an inability for the individual to discern their own intense thoughts and perceptions from objective reality. It can be characterised by anxiety and suspicion, as well as disorganised thinking that leads to confusing or nonsensical speech and hence difficulties in holding a conversation.

The hallucinations experienced by Pierce are, by contrast, for the most part both coherent and convenient. His professional insights into human behaviour are often enhanced, during the course of an investigation, by hallucinations of characters that offer him advice and lead to breakthroughs in his reasoning. Far from disorganising his thought processes, these intrusive imaginings are shown time and again to represent subconscious leaps that advance the investigations in which he is involved. Essentially, they form a handy plot device. For schizophrenics, however, the voices they hear are far more likely to be critical and unfriendly, generating stress and confusion.

Another area in which Perception falters is in how it falls back on generating comedy from Pierce’s condition. When he bluntly calls an attractive student out for coming on to him then later has Lewicki check that the same student isn’t a figment of his imagination when she is stood practically half-naked in his office, any sense of drama quickly veers towards farce. And when he seeks to alleviate a moment of anxiety caused by the chaos of a police station house by jumping on a chair, donning headphones and conducting the orchestra to which is listening, Moretti is given one of several quippy asides that brand the professor she supposedly deeply admires as “eccentric” or “crazy”. Such dialogue does her character no service, and undermines any serious consideration of Pierce’s condition.

Whist its core portrayal of the condition is fundamentally flawed, it is fair to note that Perception does have some merits. McCormack’s portrayal of Dr. Daniel Pierce is one of the most sympathetic aspects of the episode, and goes some way to elevating the content. Whilst the script calls upon the character to be more charismatic and brilliant than everyone else around him, McCormack makes the most of his more vulnerable moments. A recurring hallucinatory figure is Natalie Vincent (), with whom Pierce has conversations that reflect an internal dialogue, such as during this episode following the incident of the student making a pass at him:

Elsewhere in the episode, some of Pierce’s attitudes ring true, such as in his mistrust of pharmaceutical companies—which, as with my previous post, are here represented as insidious, greedy and corrupt—and in his comments about how those suffering mental illness are more likely to find themselves on the wrong side of the law, and to be treated harshly by its institutions.

Both because and in spite of its serious flaws in both concept and delivery, one thing that Perception has done successfully is to promote much discussion on schizophrenia and how it is represented onscreen. Individuals with personal experience of the condition have compared fiction to reality and criticised the episode’s failure to explore the pitfalls of being an unmedicated schizophrenic. Major media outlets have highlighted its reliance upon gimmickery or used the series as a springboard to address the wider question as to why primetime television has failed to understand the condition.

Dr. Pierce’s closing speech to his class offers further food for thought. In challenging what it is to be “normal”, it blurs the lines between mental wellness and mental illness in a way that encourages consideration of the individual:

For all the faults inherent to its setup, it is perhaps unfair to judge Perception too severely on the sole basis of its first instalment given the potential for character development offered by an ongoing series, and this blog may well return to the series for precisely that reason. It is also fair to say that the series’ representation of schizophrenia is light years ahead of the myth of “split personality” arguably perpetuated by such celebrated films as Psycho (1960), The Shining (1980) and Fight Club (1999).

If future instalments of Perception—which, at the time of writing, is about to launch its third season—can forsake a reliance upon formula, cliche and misplaced humour, and instead champion nuance and authenticity, then perhaps the series may yet add something positive to the perceptions of this illness held by its millions of regular viewers.

May 5, 2014

Millennium “Walkabout”

Title: Millennium “Walkabout“

Writers:

Director:

Network: Fox

Original Airdate: 28 March 1997

Millennium (1996-99) was a shoe-in to feature in this blog, given my enduring love and admiration for the series, its consummate and considered artistry, and its dense, psychological subject matter. It tells the story of Frank Black (), a legendary forensic profiler gifted with the ability to see into the minds of killers, and via whose singular perspective each episode explores the various manifestations and nature of evil in the modern world. I recently co-edited a book, “Back to Frank Black” (2012), featuring detailed analysis of the series’ themes alongside versions of interviews originally conducted by the titular campaign to see this unique criminal profiler return to our screens.

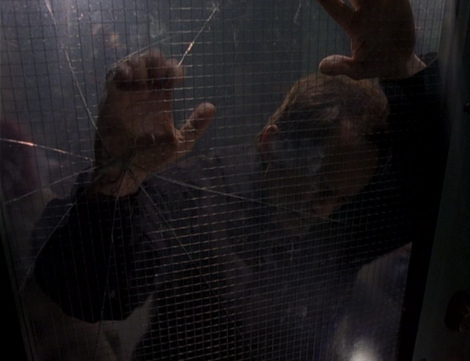

In the course of putting the book together, I revisited many, many episodes from all three seasons, yet one I hadn’t re-watched until now forms the subject of this entry: “Walkabout”. It is, in many ways, one of the most unsettling instalments of all in Millennium‘s first season, and this is in large part due to the circumstances in which we first meet Frank Black during a jarring teaser sequence. Locked in a room full of people in severe states of agitation, arousal or anxiety, he violently and repeatedly pummels the door’s reinforced glass pane in a vain attempt to escape. This is Frank Black as the audience has never seen him before at this point in the series: enraged and out-of-control. Rather than entering the scene of an horrific crime as a restrained consulting investigator, the hero’s out-of-character behaviour and subsequent disappearance represents the episode’s initial mystery.

Fellow consultant and Millennium Group member Peter Watts () shows up at Frank’s house to seek assistance from his wife Catherine (). Frank turns up soon after, battered and unconscious, in the town where he had been on assignment, with no memory of what happened to him. Piecing together the events that led up to his disappearance, Frank is subsequently able to track down a discredited doctor that he had visited, and who monitors experimental and clinical trials of as yet unapproved prescription drugs. Frank subsequently learns that he was present during such a drug trial, but that another substance was unwittingly taken by the participants through a water dispenser—one that led to the frenzied behaviours seen in the teaser sequence. Sandy Geiger (), a forensic lab technician, explains what that substance was:

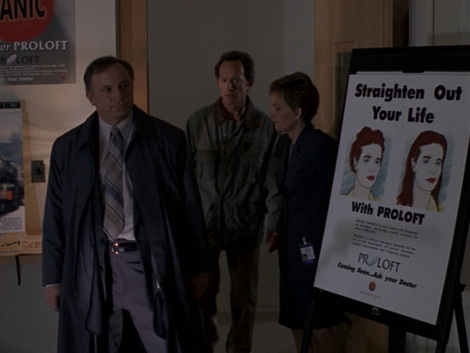

Proloft, the fictional drug that features in “Walkabout”, is actually named for two very common prescription drugs, Prozac and Zoloft, that are used to treat a number of conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders. Between them, recent figures indicate that they have accounted for over sixty million prescriptions per year in the US alone. Whilst undoubtedly helpful to some patients, concerns have often been raised regarding the overprescription of anti-depressants, resulting in side effects being suffered unnecessarily by those experiencing milder symptoms that might have better suited other forms of treatment. Meanwhile, of course, pharmaceutical companies report huge profits.

Society’s blindness to such overprescription is the central conceit of the episode’s antagonist, Hans Ingram (), who works for the pharmaceutical company that markets Proloft. Disillusioned with his work, his scheme is to highlight these dangers by giving people a drug that has the opposite effect. Having initially contaminated the water that Frank Black drank at the family clinic, Ingram’s final dramatic statement is to have free samples of the drug handed out an an office location. Mass panic ensues, all of which Ingram observes via cameras from the building’s security room. It is here that Frank Black confronts Ingram, who explains his spurious motive:

With Ingram taken into custody, one central mystery still remains. Why was Frank Black at the clinic in the first place, and why had he met with the discredited doctor?

Frank’s “gift” is first introduced as being both a gift and a curse; it enables him to see into the minds of killers, but it also poses a risk to his own sanity. Prior to the start of the series, he has retired from the F.B.I. having suffered a breakdown. In “Sacrament“, a preceding episode, Frank’s daughter Jordan () first shows signs that she may have a similar facility to that of her father in the wake of her aunt’s abduction. It transpires that, fearful for what her future may hold in store, Frank had explored the nature of the trials to seek a potential cure for his “gift”.

Whilst the exact nature of Frank’s facility remains somewhat nebulous throughout Millennium, it is here for the first time represented as something akin to an illness, and potentially a genetic condition at that. The allusions to mental illness are clearly drawn and, in the context of the episode’s plot and the audience’s knowledge of Frank’s chequered past, it makes for a powerful comparison. The episode ends with Frank and Catherine—always devoted parents—discussing the implications for their daughter:

Millennium would sometimes be criticised during its first season for being nothing more than a “serial-killer-of-the-week” procedural series. It is, however, nothing of the sort, and much more besides. It is a mature and dense series, employing Frank Black’s singular perspective upon the crimes he encounters as a prism through which to view the modern world. It explores evil in many guises, and in “Walkabout” it suggests that, in allowing ourselves and others merely to be drugged into acquiescence, we do a great disservice to society. It is a powerful message dramatically delivered, and one that still rings true to this day.