Adam Chamberlain's Blog, page 2

October 30, 2016

The Living and the Dead

Title: The Living and the Dead

Writers:

Directors:

Network: BBC One

Original Airdate: 28 June – 2 August 2016

For Halloween, I wanted to revisit a recent six-part series that was a major fixture of BBC One’s summer schedule: The Living and the Dead. Set just before the turn of the twentieth century in rural Somerset, it charts the return of a pioneering Victorian psychologist to his family home, one that unearths some personal ghosts—such as the death of his young son in the grounds of the house—and some seemingly real apparitions. Of particular interest to me (and, naturally, this blog) is how it conflates belief in and experiences of the paranormal with states of mind and, most notably, mental illness.

Said psychologist is Nathan Appleby (), and he is accompanied by his city-born second wife, Charlotte (). The duo do their best to adapt to the farming way of life, led according to the rhythm of the passing seasons but increasingly disrupted by the advances of the Industrial Revolution. As they do so, however, Nathan finds himself drawn into the psychological disturbances of some of the locals, before events take a decidedly sinister turn with devastating personal consequences.

In an interview with the excellent resource that is the BBC Writers Room, creator Ashley Pharoah described the series as “eerie rather than horror,” and exploring “the skull beneath the skin of English pastoral” in much the same way as Penda’s Fen (1974) and other classic folk horror fare. Pharoah describes the setting as helping to suggest the tone of the series, with events taking place at a “moment in our history when the Industrial Revolution collided with a way of life that hadn’t changed for centuries, a post-Darwin world where God was dead. If ghosts and demons were ever going to rise up surely it would have been then and there?”

The Living and the Dead expertly crafts such a tone in so many aspects of its production: in its cinematography and lighting, its soundtrack of sombre folk song arrangements by The Insects, the stand-out performances of the cast, and in the tangible shift in the seasons represented across its five-month shooting schedule.

Nathan’s area of interest is described as “aberrant behaviour” and, even as he sets out to make a new start in life, he finds much of this to explore amongst the locals whose value systems are characterised by superstition and ancient folklore. Its first episode introduces us to an adolescent girl seemingly inhabited by the spirit of an evil old man, which Nathan theorises is an expression of fear of her own sexuality. When challenged by the girl as to whether or not he believes in ghosts, Appleby replies, “I believe in an open and scientific mind. I have certainly seen people haunted, but only by an aspect of themselves—never by a ghost.”

Nathan’s area of interest is described as “aberrant behaviour” and, even as he sets out to make a new start in life, he finds much of this to explore amongst the locals whose value systems are characterised by superstition and ancient folklore. Its first episode introduces us to an adolescent girl seemingly inhabited by the spirit of an evil old man, which Nathan theorises is an expression of fear of her own sexuality. When challenged by the girl as to whether or not he believes in ghosts, Appleby replies, “I believe in an open and scientific mind. I have certainly seen people haunted, but only by an aspect of themselves—never by a ghost.”

Subsequent instalments see Nathan take on such cases as a young boy who turns out to be haunted by the spirits of long dead workhouse orphans, and a young schizophrenic man receiving inciting messages from a woman murdered as a witch. As his involvement in increasingly paranormal experiences as a consequence of his professional interests deepens into a preoccupation, Nathan finds himself haunted by visions of his dead son alongside other strange manifestations that he struggles to explain.

Nathan Appleby’s series arc is an interesting one, as his experiences combine with his personal history to challenge his worldview and his very perception of reality. As Colin Morgan explains of the perspective and state of mind of his protagonist:

“He has been educated his whole life to believe that aspects of the supernatural are aspects of the mind that present delusions, that present visions, [and] are very much explained scientifically. That a vision is not reality; it’s a a delusion of something in the mind that has happened, it’s a version of the self that is trying to deal with some problem or to try to protect the core self from something else much grander, much bigger, like a trauma or a bad experience. To start to see things that challenge that belief and the years of education that he’s had is very unsettling for him. And Nathan does begin to experience things both through the locals and himself that puts him to the test; he’s forced to really thread the line and the divide between the scientific and the supernatural. You get the impression that land holds trauma, that land holds pain, that land holds memories, and this digging up, this unearthing of the land itself gives a feeling of something else being unearthed, of being unsettled and disturbed, and I suppose that seems like it’s a catalyst for things that happen.

As the series approaches its climax, any sense of ambiguity disintegrates along with Nathan Appleby’s own sanity. In the penultimate instalment—at Halloween no less—spectres of the dead manifest, such as those of Civil War soldiers from over two centuries ago. Meanwhile, in the present day, we meet a young woman with a connection to the Victorian Appleby suffering her own mental distress in the form of postpartum psychosis. Ultimately, their mental disturbances are equated to some sort of an ability to commune across time, and the collective memories of past and present generations collide.

As the series approaches its climax, any sense of ambiguity disintegrates along with Nathan Appleby’s own sanity. In the penultimate instalment—at Halloween no less—spectres of the dead manifest, such as those of Civil War soldiers from over two centuries ago. Meanwhile, in the present day, we meet a young woman with a connection to the Victorian Appleby suffering her own mental distress in the form of postpartum psychosis. Ultimately, their mental disturbances are equated to some sort of an ability to commune across time, and the collective memories of past and present generations collide.

The allegory to explore Nathan’s trauma through grief is clear enough but, sadly, this is well-trodden territory that perpetuates myths of self-deception that mental illness conveys special powers. Suddenly, Appleby’s instincts and philosophy are no longer presented as ground-breaking or forward-thinking, but directly at odds with the reality of this world. In one sense this sensibility contributes to an ingenious and dramatically satisfying conclusion, however it sits uneasily with me in terms of the mental health-related threads left hanging or, worse still, implicitly proffered.

There had been some speculation—recently put to rest—that the BBC might commission a second series of the drama, something that would have felt to me to be superfluous and to have risked miring the series further in its generation-jumping twists without furthering its central themes. Ultimately, what might have been a series well-positioned to offer a genuinely fresh insight into our widespread belief in the supernatural ultimately revealed itself to be a different animal entirely, and for me that felt like a missed opportunity. It is, however, still very much worth a watch on its own merits as a modern piece of psychological and folk horror, and not least right now given ’tis the season for such fare.

The Living and the Dead is available for download from the BBC Store, to view online at BBC America and Amazon, and on DVD and Blu-Ray.

March 31, 2016

Hannibal “Buffet Froid”

Title: Hannibal “Buffet Froid”

Writer:

Director:

Network: NBC

Original Airdate: 30 May 2013

Late last year I savoured the final, dramatic episodes of Hannibal (2013-15), a series for which I have come to have an increasingly strong appreciation. The artistry inherent in so many aspects of its production—in writing, cinematography, direction, performance, and music—is supreme, such that I’m still baffled as to how few awards or even nominations the series garnered during its three-season run. This was a series of which it can truly be said that it pushed the boundaries of what television—and not just U.S. network television, on which it aired—could portray. Based upon characters in Thomas Harris‘s novel Red Dragon (1981) and alongside a frequently baroque predilection for violence and gore, it explored the relationship between a single criminal profiler/patient, Will Graham (), and a serial killer/psychiatrist, Hannibal Lecter (), to unparalleled extremes.

Diverting from Harris’s original novel, Hannibal positions Lecter as the appointed supervisor to Will Graham’s mental wellbeing at the instruction of Jack Crawford (), head of the (now defunct in reality) Behavioral Science Unit at the F.B.I.. Unbeknownst to either Graham or Crawford, however, the very man to whom the celebrated forensic profiler’s care has been entrusted is a shrewd, cannibalistic serial killer. Fascinated by Will’s empathic ability to visualise the crimes he investigates, Lecter seeks to turn the profiler into the very predator he seeks, thus creating a proxy for the crimes he commits in order to satisfy his cruel appetites, even as the pair form a close bond and a mutual respect for one another. It is an arc that significantly changes the set-up of the novel from which the series is derived but, in so doing, sets up a fascinating dynamic between the pair.

How, then, does such a singular creation handle its presentation of mental health? In terms of an episode that I thought would fit well with this blog—at least for its first appearance—we need to go all the way back to one of the latter instalments from the series’ first year. “Buffet Froid” marks a further escalation in the season’s ongoing focus upon this extraordinary psychological manipulation of Graham by Lecter. Will has been suffering periods of lost time, mental instability, and violent hallucinations during the course of his work, and Dr. Lecter has been seeking to convince him that he is becoming disengaged from reality.

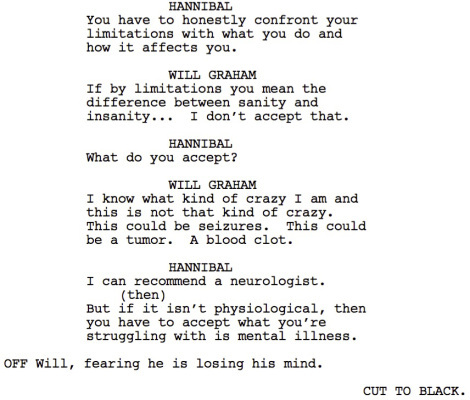

The script for the episode is published on showrunner and executive producer Bryan Fuller’s production company’s website, as are those for the entire series. It makes for a great read in and of itself, not least to unpick the often dense, detail-laden dialogue. In this scene early in the episode that employs one of the series’ trademark narrative devices, Graham and Lecter are engaged in an involved consultation at Hannibal’s practice:

Will is correct in his assertion that he is physically ill; he has encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain with a range of symptoms that include those from which he is suffering. But it suits Hannibal’s purpose to guide his ward away from such convictions, and instead to convince him he is mentally fragile in such a way as to create that very fragility.

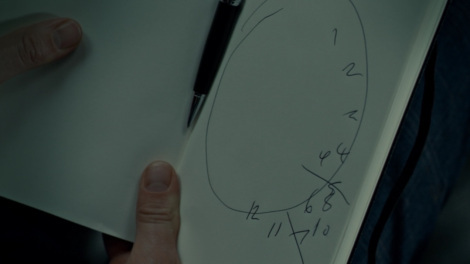

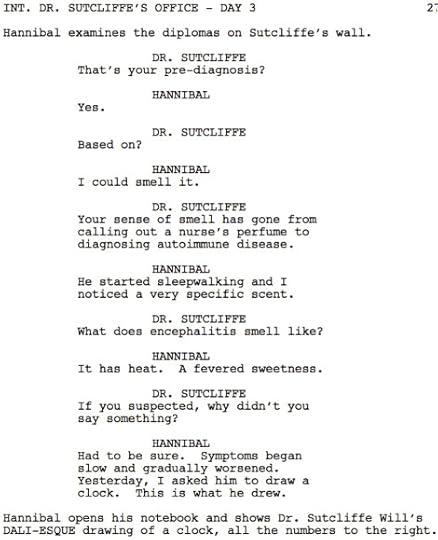

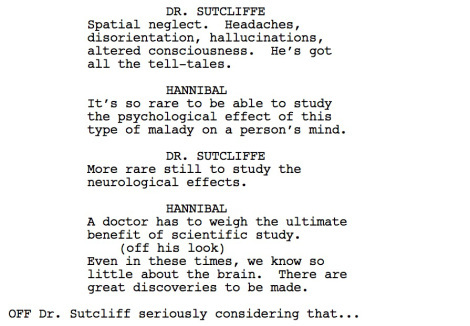

It goes without saying that Dr. Lecter’s behaviour is wholly unethical (as were murder and cannibalism, last time I checked), but he is quite successful in persuading another key medical professional to join his cause. Hannibal solicits Dr. Donald Sutcliffe () to his deception before going on to kill him by the end of the hour in order to cover his tracks. Sharing his suspected diagnosis of encephalitis, Lecter engages the neurologist’s professional curiosity:

An interesting aspect of this episode to me is how it considers the close interplay between physiological and mental symptoms and conditions. As Hannibal puts it during his discussions with Sutcliffe, “I was always drawn to how the mind works. I found it much more dynamic than how the brain works.“

Indeed, such considerations go towards potential explanations for Will Graham’s almost supernatural powers. The filmic device used by the series envisions the profiler internally turning back the clock and acting out the murders when at a crime scene, which Crawford describes to Lecter in this episode as “a mild form of echopraxia“, a condition which invokes the involuntary repetition of someone else’s actions and has been linked to to the autistic spectrum and schizophrenia. Hannibal refutes the suggestion, suggesting instead that Will “doesn’t just reflect, he absorbs” during this process as a result of having “too many neurons” in his brain.

Crawford’s echopraxia explanation certainly feels like a stretch given Graham’s recreations of murders tend to be complex and involved in nature. And this also touches upon another challenge of credibility with which Hannibal struggles: the very notion that Will Graham would be allowed to continue consulting for the F.B.I. were there even a suspicion that he was suffering from a debilitating condition, especially given his extreme behaviour by this point in the season. It is a conundrum the series explicitly acknowledges by giving Jack Crawford this very battle of conscience, but it expends believability in the process. Perhaps it seeks to suggest that Will’s condition is the unavoidable outcome from his line of work. As the profiler counters when Jack asks him if he has pushed him too far: “Do you have anybody that does this better unbroken than I do broken?“

Ultimately, Lecter’s deception continues as Will receives falsified results from an MRI scan:

As with other series I have explored in this blog to date, whilst Hannibal is undeniably detailed and considered in its presentation of mental illness, authenticity is perhaps not its prime objective. In the special features on the DVD release, Bryan Fuller lays out its central conceit as he singles out cinematographer ‘s contribution:

[He] really struck such a fantastic aesthetic for this show that is all about the contrast between lightness and dark. And if we are carrying that principle through to how Mads Mikkelsen always approached the character [of Hannibal Lecter], which is not of a cannibal psychiatrist but actually of Lucifer himself, the fallen angel who was smitten with humanity and mankind and fell for them, and is now drawn to a very pure man in Will Graham. So that mythology is always one that, ever since Mads suggested it, I can’t get it out of my head. And in my mind that is the reality of this show, which is that it is a parable of good and evil.

In pure storytelling terms, Hannibal is a fascinatingly multi-layered creation with strongly-defined themes. Even as Will Graham seeks to rebuild the story leading up to the crime scenes he explores by reliving them as a mental construct, so does Hannibal act to manipulate Will’s personal narrative. Furthermore, the case-of-the-week killer in “Buffet Froid” is a disturbed young woman with Cotard’s Syndrome, a delusional state in which the sufferer believes they are dead, and which is coupled with an inability to recognise faces (a facet of the condition that becomes crucial to the plot). With an array of mental illnesses offered in this instalment alone, the lines between objective truth and distorted perceptions—both of the self and of others—start to blur.

The complexity with which it wields its armoury, not least in its heady mix of obscure conditions, does also have a tendency to leave Hannibal feeling at times somewhat over-engineered, and notably so in this instalment.It is, however, never less than compelling. And arguably is less concerned with hyper-reality than it is in exploring its aforementioned central character dynamic. If the tension as to whether or not Will Graham truly might become the very kind of killer he seeks—with Nietzsche‘s oft-quoted maxim that “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster“—feels an unlikely in the context of a long-form series of this nature, then any prospective but as yet uninitiated viewer should consider that Hannibal sets out to play the long game in this regard as the events of all three seasons gradually unfold.

Ultimately, what Hannibal presents the viewer is an intricately-constructed narrative that requires and—through the compelling performance of its leads—demands the viewer’s full attention. It is those central performances that also ground the content with a sense of believability in spite of itself. The television landscape feels poorer for its absence, not just for its striking visuals and strong production values at every level, but also for its uncommonly detailed considerations of psychiatry and mental illness as key components in the eternal struggle between good and evil embodied in its vivid characterisations of Will Graham and Hannibal Lecter.

January 24, 2016

EastEnders “Stacey Branning—On the Edge”

Title: EastEnders

Executive Producer:

Network: BBC One

Airdate: December 2015 to January 2016 (and ongoing)

For this edition, rather than delving into a single episode of television, I wanted to take a look at an ongoing storyline in BBC One’s flagship serial drama EastEnders (1985 – ), set in the fictional Albert Square, Walford. The story in question is one that has been carefully constructed and is playing out over a number of months: that of Stacey Branning‘s () struggle with postpartum (also known as puerperal or postnatal) psychosis. For an overview of the storyline, plus interviews with the key actors and other members of the creative team, the BBC iPlayer has an exclusive documentary currently available, entitled “Stacey Branning—On the Edge“.

Postpartum psychosis is a rare but severe and disruptive psychiatric illness suffered by around one per thousand mothers shortly after giving birth, and characterised by mania, depression, confusion, and delusions. Mothers with bipolar disorder are particularly at risk, with up to one in four experiencing the condition, although it is important to note that the diagnoses are separate and that not all those that experience postpartum psychosis are bipolar. Neither is there a link to post-natal depression. In Stacey’s case, though, her struggle with bipolar is a longstanding element of her character, indeed one that earned the series Mind’s Media Award for Drama in 2009.

Stacey’s episode of postpartum psychosis seems all the more plausible given the many different strands that have conspired and converged in her life over a number of weeks and months, exemplifying the kind of storytelling opportunities that serial drama offers. Her partner is Martin Fowler (), whilst her baby, Arthur, was actually fathered by his best friend, Kush Kazemi (), who is in turn married to Stacey’s bestie, Shabnam (). Whilst their respective love lives may read as a little convoluted (did I mention this is a soap opera?), Stacey’s guilt and anxiety over her circumstances actually serve to make the spark for her postpartum psychosis yet more believable. Add to the mix a long-lost sibling who has just appeared without warning and is behaving somewhat suspiciously and secretively (having not yet revealed that he is transexual), the sudden death of Stacey’s great-uncle following a family argument in her home, and—crucially—the fact that her baby was born rather suddenly on the set of Walford Square’s Nativity play on Christmas Eve, and her mental struggles start to feel much more tangible.

That link to the Nativity story is an important one, since Stacey’s postpartum psychosis has taken the form of her believing that Arthur is the son of God, and that she must protect him from the Devil and his agents, which she starts to see everywhere. (I am very interested in the links between supposed religious experience and mental illness, but that’s a topic for another time.) She takes extreme action in her misguided attempts to protect her newborn, in turn finding herself hiding out on the roof of local pub the Queen Vic during a thunderstorm, refusing to leave her bedroom, surrounding herself with broken glass so that the Devil cannot come near the baby, and much more. All in all, this might seem an unlikely storyline for a serial drama that usually concerns itself with the grit of day-to-day existence in London’s East End.

Interesting, too, has been the uncharacteristic use of camera, sound, and special effects in the series to illustrate Stacey’s perspective in her psychosis. Thunder and lightning more befitting of a horror film were the backdrop to dramatic moments on the roof of the Queen Vic, whilst sound design and camera effects have been used sparingly to illustrate Stacey’s point of view. These stylistic flourishes are particularly striking given how unusual they are in serial drama, and how much of a departure they represent from the series’ usual look and feel, and as such they really pay off. But none of these effects should take anything away from Lacey Turner, whose performance has inhabited and defined the character of Stacey on-and-off for over a decade, including the ups and downs presented by her bipolar disorder.

, a senior researcher on the series, describes in the aforementioned online documentary how he first heard of the condition and contemplated it as a potential storyline:

In January 2015 I was talking to Professor Ian Jones, who is a Professor of Psychiatry and an affiliate to Bipolar UK. And he mentioned in our conversation, “Have you heard about postpartum psychosis?” And I said, “No—tell me more.” And the more he told me about it, the more I thought, “Wow, this could be very dramatic, but also it feels like an issue we’ve never seen before on TV.” So it’s dramatic and novel, and perhaps in need of being told.

Dominic Treadwell-Collins, formerly a story producer on the series and now its executive producer, has overseen a number of high-profile and impactful storylines in the serial drama during his tenure to date, such that EastEnders feels like it is going through one of its peak periods right now. He was, however, initially sceptical that some of the details of Stacey’s psychosis—notably its strong religious element—might be going too far:

When it was first pitched, and Alex Lamb and the story team and the writers all came to me, Alex sat with me and said, “What if Stacey thinks that Arthur is God?” And I immediately balked a little at it, because it’s really out there. But this came from real stories. Alex said that there are several cases of mothers believing that their child is God.

That, perhaps, is one of the keys to this arc’s success: an angle that is at once dramatically interesting and genuinely novel, whilst also being truthful. And the creative team were adamant that they needed to get the details right. Treadwell-Collins goes on:

As with any storyline, research is really, really important. And it was important for us to get all the research fully done, and get all the stories from real life situations in our heads and give them to the writers, so that we could use different elements of that with telling the story.

In terms of that research, the production team worked closely with the charities Bipolar UK and Mind, which has a page on its website dedicated to its collaboration over the storyline and postpartum psychosis itself. As befits the BBC’s public remit, the BBC Action Line features links to resources on a range of issues related to pregnancy, birth and children. Furthermore, there is a detailed blog post on the BBC’s EastEnders website in which representatives from Mind talk at length about their input. That article also highlights why Mind sees such collaboration to be of genuine and significant importance to the work they do:

At Mind we are quite unique, as alongside our traditional media team who help journalists and promote the work that Mind do, we also have a media advice service dedicated solely to ensuring that onscreen portrayals of people with mental health problems are accurate and sensitively done. A lot of our work involves working with serial dramas. Some people may question what value this has, but we know that serial dramas have an amazing opportunity to shape and challenge attitudes, raise awareness, and dispel myths. Watching a character on screen with a mental health problem may be the first time someone watching is exposed to mental health problems. We also know that millions will happily follow the shenanigans of the Square weekly, but would never dream of switching on a documentary.

I count myself as a follower and supporter of Mind’s work, and I heartily agree with this sentiment. Indeed, it is the very reason I was inspired to create this blog, and to consider writing something that touches upon mental illness in a way that I hope is fresh and original, and that therefore has the potential to be genuinely impactful.

As the BBC has itself reported, British soaps pride themselves on tackling difficult and taboo subjects, and EastEnders in particular often does just that. This is arguably a contributing factor to its reputation as being characterised by a somewhat dour atmosphere, for which it is often lampooned. It is therefore important to note, too, the intention to present a perspective on postpartum psychosis that, whilst truthful, is ultimately shown to be optimistic. That might seem hard to contemplate given the low points the characters at this story’s heart have endured. Most recently, Stacey has been sectioned against her will and separated from her baby, in scenes that have highlighted a lack of mother and baby facilities on psychiatric wards, and also the impact upon the father in the relationship by highlighting Martin’s own struggle on how to react and how to cope. Yet, with this still very much an ongoing storyline, Treadwell-Collins promises, “Going forward, there is joy. There has always got to be hope out there.”

Thus far, the response to Stacey’s storyline has been overwhelmingly positive, as the Mind consultants point out:

The reaction to the storyline so far on social media and within our supporter network has been overwhelmingly supportive. Many have said that they had never heard of this condition before, which is one of the reasons for doing this storyline. Some women who have also been through this experience have said that it is hard to watch but incredibly important to get out there. They have also said that watching Stacey is like watching themselves. There are some who may think that this is a ‘typical’ soap opera storyline that wouldn’t happen in real life. However the women we have worked with say that their ‘real’ stories are far darker and really not suitable for television.

Stacey Branning’s ongoing storyline in EastEnders is, then, that all-too-rare circumstance: popular and engaging television that is meticulous in its presentation of mental illness, both entertaining and genuinely informative. In this regard it is, therefore, for me right now setting a standard to which all such drama should aspire.

September 11, 2015

The Visit

Title: The Visit

Writer:

Director:

Studio: Universal

Release Date: 11 September 2015

I am, in this edition, taking another break from the established convention for the blog: to write about something brand new, on its release date no less. Once again that is a movie, and I am doing so having had the privilege of attending one of The Visit‘s many preview screenings and Q&A sessions with its writer-director, M. Night Shyamalan—this one last week in London at the lovely, characterful Picturehouse Central courtesy of Den of Geek. Given it is a brand new release I should preface this piece with a word or two of caution that, due to the nature of the topics I consider, this post contains some MAJOR SPOILERS about the content of the film. So please only read on if you have already seen the movie, or if you have no objection to learning some key points about its plot.

M. Night Shyamalan is to be commended as a film-maker who takes risks and who seeks to make original films of artistic merit. Indeed, my appreciation of his canon has only been amplified by author John Kenneth Muir‘s typically detailed and thoughtful recent series of posts exploring Shyamalan’s work. But my concern here on the blog remains as follows: are the film’s representations of mental illness appropriate and accurate, and what do they convey in the context of the film when taken as a whole?

The Visit tells the tale of two children, teenager Becca () and her younger brother Tyler (), who are sent by their single mother () to stay with her parents for a week whilst she goes on a vacation of her own with her new boyfriend. Becca and Tyler have never met their grandparents, as they have been estranged from their daughter for fifteen years following a falling-out.

Across the course of their stay, the behaviour of Nana () and Pop Pop () becomes more and more bizarre. They lay down a strict rule that the children should not come out of their rooms after nine-thirty at night, explaining that they are old and need peace and quiet from this time. But Becca and Tyler hear strange sounds during their curfew, and, their interest piqued, sneak a look only to find Nana embarking on strange behaviour after dark: vomiting openly as she walks the hallways, clawing at walls whilst naked, and the like. Meanwhile, after becoming suspicious of Pop Pop’s secretive behaviour in the toolshed they learn of his incontinence and that he hides his diapers there before burning them.

Events take an even more sinister turn as Becca—a would-be documentary filmmaker whose camerawork makes for the audience’s point of view for much of the film—and Tyler seek to delve deeper into these strange goings-on. Nana and Pop Pop’s behaviour becomes yet more unsettling and, ultimately, monstrous as the film builds the tension towards a disturbing climax.

One of The Visit‘s earlier titles was Sundowning, and the implication during at least part of the film is that this is the root cause for Nana’s bizarre behaviour. Sundowning is a known and defined phenomenon wherein some dementia sufferers suffer increased levels of confusion and agitation after dark. Its symptoms do not, however, suggest the increasingly murderous and often calculated intent that Nana exhibits towards Becca and Tyler.

The Visit‘s big reveal (did I mentioned SPOILERS?) is that this elderly couple aren’t Becca and Tyler’s grandparents after all, but rather escaped psychiatric patients who have murdered their real Nana and Pop Pop and taken their place. Our mental illness focus thus shifts from dementia to, it is intimated, schizophrenia. And I’m afraid my heart sank at this plot development. The audience is to believe that an elderly couple suffering a condition characterised by psychosis and paranoia have concocted an elaborate scheme to play-act the role of being grandparents to these children in order to wreak a week-long campaign of terror and then, ultimately, to murder them. It is, quite frankly, ludicrous—a contrivance as out-dated as it is improbable.

Towards the end of the Q&A that followed the screening I attended, there was an uncomfortable question posed of Shyamalan from someone who had just lost a grandparent to dementia, asking whether or not he was concerned that The Visit acted to demean or demonise sufferers. The writer-director’s response was, I felt, somewhat dismissive, stating that this was not his intent and that he hoped it would not be interpreted in this way, as his intent was merely to “have a bit of fun” with the set-up. For me, though, the question was a reasonable challenge, and, if anything, the response only amplified the concern.

Is it churlish, then, to judge these aspects of The Visit on terms which it in no way seeks to represent itself? (And especially so having been invited to a free preview screening intended to prompt word-of-mouth momentum for the release?) From my perspective I’m afraid I don’t see it that way, and here is another reason why. During the Q&A after the screening I attended, Night spoke several times about the “human drama” at the heart of his approach to filmmaking. In fact, he went so far as to his state that his “secret formula” is to “make dramas and pretend they’re genre movies”.

I don’t doubt this, and, indeed, it is as true of The Visit as it is of his other films. He spoke of how the movie is very clearly to him about the need for forgiveness and letting go of anger—from the children’s mother towards her own parents having left it too late to reconcile with them, and also in her pleas to the children over their own estranged father. Night went on to tell of how that theme was inspired by circumstances in his extended family, and how this is tied to the culture of pride above all else in many Indian families.

Yet, if anything, this mix of human drama, comedy and horror that combine in The Visit to produce such a unique tone only makes his representation of the elderly couple all the more jarring and discomfiting. If this were an out-and-out horror movie with no subtext then I could perhaps shrug it off, but the fact that it seeks to be underpinned by a human element eviscerates any “fun” quotient for me, and undermines that dramatic core.

I am aware, too, that the representation of the “grandparents” can be taken to be non-literal: that the “real” Nana and Pop Pop have been wrongly demonised in their own way by their daughter until the truth about them is revealed, and that the sustained lack of contact between family members has led directly to the tragedy that befalls them. Even so, for me, the representation of either condition put before the audience—dementia or schizophrenia—is deeply problematic, and could have been handled in a more sensitive way whilst still delivering the dramatic message at its twisted heart.

There were elements of The Visit that I appreciated. Night said how he always tries to cast theatrically-trained actors as he does long takes. This was particularly important to him in the case of Dunagan and McRobbie as he was seeking “delicate actors” to ground their performances in a “value system”. Both actors therefore had an internal logic for even the more bizarre behaviours they were called upon to enact as opposed to just trying to scare the audience, which therefore translates to a much more unsettling and confounding viewing experience as a result. This interests me as it was particularly effective in that intent and speaks to the artistry of both director and actors, but I’m afraid my deep-seated reservations really tarnished the whole experience for me.

Clearly, M. Night Shyalaman never set out to make a movie that was in any way representative of either dementia or schizophrenia, and perhaps audience members less encumbered by my concerns on the topic of how mental illness is represented will enjoy the film on its own terms. Night spoke, too, about how a movie is for him like a “date with the audience” and how he needs to to meet them in the middle ground of their expectations in order to deliver a satisfying experience whilst he sneaks in his true message. Perhaps that explains some of the creative choices he made in The Visit, and perhaps it will deliver a very successful movie in many respects as a result. I only wish it could have done so whilst also serving to educate and redefine the common understanding of two such debilitating conditions, as opposed to reinforcing out-dated and self-defeating stereotypes.

August 11, 2015

The Fisher King

Title: The Fisher King

Writer:

Director:

Studio: TriStar Pictures

Release Date: 27 September 1991

It is a year ago today that we lost one of the great actors of his generation: . For this blog’s first foray into the world of cinema, I thought it would therefore be timely—and a tribute of sorts—to consider one of his stand-out roles, a portrayal that is arguably all the more resonant and affecting given his loss, as director Terry Gilliam himself commented shortly after Williams’ death. It also offers some insight into the potentially transformative nature of an actor’s performance in relation to the original screenplay, and so this post will consider that in respect to its core consideration of onscreen representations of mental health conditions.

The film opens with New York shock jock Jack Lucas ( taking aim at callers to his late-night talk radio show, only for his arrogant patter seemingly to prompt a regular and already unstable caller into a shooting spree at a restaurant. There is an interesting passing commentary on the psychology of mass shootings (a much broader topic and one for another post), whilst the rest of the film focusses upon the fallout from that event as seen from the perspectives of both Lucas and Parry (Robin Williams), a man who was widowed during the attack and whose life changed dramatically as a result.

Parry is in truth the troubled persona of Henry Sagan, an academic who, unable to cope with his loss, had initially slipped into a catatonic state in the wake of his wife’s death and now lives amongst the homeless as he struggles with mental illness. Jack Lucas’ life has also been transformed in the wake of the shooting; the narrative re-joins his life three years on to find him having fallen from grace and now a depressed alcoholic, working in a video store to make ends meet.

The Fisher King is a film that sees wildly comic moments sit alongside tragic drama, and demonstrates how—when judged carefully—they can be fitting bedfellows. That quality also reflects an apparent truism in that the lives of many deeply talented comedians and comic actors appear to have been touched by tragedy, depression, or some combination thereof. It is Williams’ own trademark manic comic talents that are initially on display, as he appears on the scene to rescue Lucas from an attack by two thugs even as the former shock-jock was set to throw himself into the Hudson to commit suicide at the end of a particularly bleak night.

That rescue is in itself surreal and hilarious, and this tone is carried forward into the following day’s events as Lucas wakes up in Parry’s dishevelled yet intricate makeshift basement home. In the scene that follows, a manic Parry talks to imaginary “Little People”, and, in a brief hint as to his underlying trauma, stops Jack from exploring a hidden shrine he keeps to his dead wife. Parry then begins to explain to Lucas that he has been chosen to aid him on his quest to find the Holy Grail, and of the Arthurian myth of the Fisher King in a version of that tale somewhat re-imagined to reflect the film’s narrative and its thematic search for healing. Parry has all but forgotten that this was a topic on which he had lectured and written a thesis in his former life; in his deluded state, this academic interest from prior to his personal tragedy has morphed into an imagined reality:

The precise nature of Parry’s mental illness in the film has been the subject of some debate, with suggestions that his psychosis—not least the transformation of the Fisher King myth into a strongly-held belief of his personal reality—suggests schizophrenia as opposed to the more appropriate condition of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). At least one perspective, however, offers evidence that suggests psychosis can indeed be a symptom of PTSD, especially when having suddenly experienced the violent death of a loved one.

Parry’s grief, illness and fears are embodied by the Gilliam-esque Red Knight, an apparition the untimely appearances of which help grant the film a nightmarish quality that contrasts well with and toughens some of its more mawkish content. Screenwriter Richard LaGravenese—who was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for The Fisher King—credits Terry Gilliam for, during the development process, having him reinstate “a lot of the odd, weird stuff. [He added] an edge to it that is so important because the script to me could have been so sentimental that it makes your teeth hurt.”

What emerges is what Niles Schwartz termed “a film about trauma, but… clothed in a theatrical buoyancy, so as to obscure—and flee from—reality’s petrifying disorder” (something of a theme in Gilliam’s work). In terms of how mental illness is handled, Keith Phipps’ excellent article for The Dissolve described The Fisher King as “a movie- and metaphor-friendly depiction… that, had it veered off course, would have risked romanticising both instability and homelessness. As it’s handled, however, it works. Growing calmer and more coherent as the story progresses, Parry almost slips back into sanity near the end. But sanity also means remembering losing his wife when a gunman, inspired by something Jack told him on the air, shot up a bar three years earlier.”

In a sequence that perhaps best exemplifies the film’s contrasting yet complementary qualities, after finally managing to secure a double date with the eccentric Lydia () alongside Lucas and his on-off girlfriend Anne (), Parry breaks down in the street outside her apartment at the end of an evening that has brought him a rare moment of fleeting happiness. The Red Knight then makes a dramatic appearance, pursuing Parry through the streets of New York, whilst onlookers of course see just a raving, deeply-disturbed man fleeing from a hallucination. This sequence is transformed by the sheer gusto of Williams’ performance in its final version, although LaGravenese’s screenplay still reads reads dramatically on the page:

Gilliam has recalled directing this sequence, and tellingly grew concerned for Robin Williams during filming, because of just how invested the actor was in the moment:

This scene wasn’t a challenge to shoot as far as effects are concerned, but it was very hard from an acting point of view, because Robin was tearing his guts out emotionally. The interesting thing about Robin in all of those scenes was that he always wanted to do another take. He felt he had even more anguish and pain to spill out of the character. And I had to really stop him. I had to say, ‘Robin, you’ve reached a point here, way beyond what we expected. We’ve got what we needed. Now you’re just hurting yourself.’

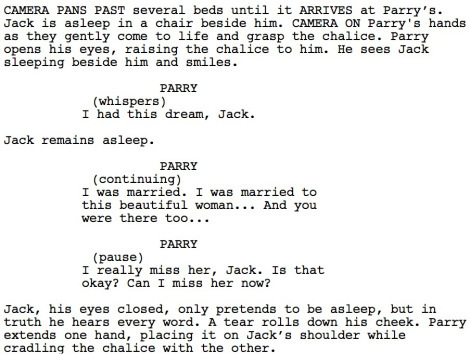

The film balances hope and hopelessness with its promise of redemption or at least acceptance of the past for both Williams’ Parry and Bridges’ Lucas, with many of its character arcs reflecting one another. In spite of himself, Jack Lucas carries out Parry’s “quest” and steals the “Grail” (actually just a trophy) from the home of an aged architect, inadvertently saving the old man from a suicide attempt in the process. In the meantime, however, after his disastrous date Parry has been set upon by the same thugs from whom he rescued Jack—the strong implication being that he sought them out in order to be put out of his misery—and is once again unconscious in hospital. Lucas delivers his prize to Parry there, who finds some sense of reconciliation when he awakes:

I often analyse the choices that I write about on this blog purely in terms of the onscreen representations of mental illness as a completed piece of work, or sometimes in reference to the original screenplay. But film-making—as with theatre or television drama—is, of course, a collaborative art. So perhaps in a sense Robin Williams’ performance in The Fisher King transcends any black-and-white considerations of the “truth” of mental illness, and offers us something yet more valuable: a soul-bearing interpretation of such material from a man who so deeply felt his own inner darkness. I appreciate that it can be dangerous to over-reach when identifying connections between actors’ personal lives offscreen and the parts they choose to play onscreen, but in this instance Keith Phipps couched it well for The Dissolve:

It’s often unwise and irrelevant to connect actors to the roles they play, and yet something about Williams’ suicide has invited it. He often played men struggling with darkness, sometimes without success, frequently men who used verbal agility and unbridled energy as weapons in the fight. Few movies put that struggle to the fore as prominently as The Fisher King.

Robin Williams’s performance in The Fisher King is often now held up in retrospectives as one of his finest. One such retrospective writes of how well-suited he and Gilliam were as collaborators, describing the director as “another funny man whose comic work dances with the horrors of the world”. I am inclined to agree with Vulture’s description of Williams’ role as Parry as “one of the most perfectly calibrated performances of his career: freewheeling in that way we know and love, but also speaking to a deep sense of loss. It’s the comic as inspired madman, as wounded warrior.” And Gilliam himself has spoken of just how committed the actor was to the role:

The last shot we had to do was Robin running at the end of this scene, in this hysterical state. You can even see the light ever so slightly beginning to come on the river in the background. But Robin was so angry because it was such a crucial moment, and he felt he’d been cheated of his ability to really give this moment his all… So, I had to go up there and tell him, ‘Robin, what we have here is very good. And if we look at the rushes and it isn’t, I promise you I will reshoot it.’ And I had to hug him basically, and hold him. I could feel these muscles that were so tense and so strong, they felt like they could easily rip my head off. But that’s what was so extraordinary about him—how he would commit everything and more to what he had to do. That’s also why I think his character in The Fisher King is in many ways the closest one to Robin, just that range—the madness, the damage, the pain, the sweetness, the outrageousness. That was the role I think that stretched him to the limits.

If you have never seen The Fisher King, or have not done so in a long time, then I urge you to do so. It is an artful, entertaining, and haunting experience shot through with the multitudinous talents of its cast and director, and with a richness to which I can’t do full justice herein. It also offers an utterly unique and valuable representation of mental illness suffered in the wake of human tragedy. And perhaps most of all, it pays testament to the comic and dramatic elements that were combined in the true genius—a word I do not use lightly—of the late, great Robin Williams.

July 29, 2015

The X-Files “Roland”

Title: The X-Files “Roland”

Writer:

Director:

Network: Fox

Original Airdate: 6 May 1994

Before I delve into any specifics, I just have to say this: I love The X-Files (1993-2002). I still remember with crystal clarity—which is saying something, as my long-term memory is terrible—the first time I watched it, sat expectantly on the floor in front of the television in my parents’ living room, and that I loved every second in spite of those heightened expectations. This was via the original UK video releases complete with their evocative cover artwork and comparatively nondescript logo, and which, sadly and inexplicably, I never kept after upgrading my collection to DVD. The series remains a strong influence upon me, and, as I mentioned in my previous post to feature The X-Files, not least so as regards one of the key reasons I started this blog. I am beyond excited at the series’ upcoming revival for a short run of episodes in 2016, and will be doing my best to keep pace with the “201 Days of The X-Files” re-watch.

It is for that reason that I now return to the series here, and offer a few thoughts on the representation of autism offered in today’s instalment in that mammoth re-watch: “Roland”, the penultimate episode of The X-Files‘ first season. It is fair to note that it is not one of the most highly-regarded outings in the series’ first year, although it is certainly buoyed by a phenomenal guest performance by as the titular, occasionally-less-than-mild-mannered janitor at a research facility.

This was noted at the time of its production, when director David Nutter sought to centre the episode upon the strength of that performance. Of Ivanek, he said, “when I knew I had him, I thought it was important to push that as much as possible, to help outweigh the frailties in the script”. He was the first actor to read for the part, and landed it immediately. He “just blew us away”, remarked series creator and executive producer in the official guide to the series. The actor himself recalls the audition, describing it as “one of the incredibly few times where I read something and thought, ‘That’s as good as I can do.'” He remains proud of the performance, adding, “It’s still on my demo reel, it’s still one of my favourite things”. Ivanek’s performance is undeniably a powerful and nuanced one, and the centrepiece of the episode.

Special Agents Fox Mulder () and Dana Scully (Gillian Anderson) meet Roland Fuller during the course of an investigation into the grisly murders of two propulsion engine scientists. As suspicions fall upon the unlikely figure of Fuller, long-hidden truths are ultimately uncovered to reveal that he is under the psychic control of the man who hired him: Dr. Arthur Grable, a scientist at the facility who died several months previously but whose consciousness survives in his cryogenically-frozen head. (Writing that sentence puts me in mind of a recent podcast interview in which he stated that every X-Files concept sounds ridiculous when spoken out loud.) In a further twist, Grable and Fuller are revealed to be identical twins who were separated in childhood, a trauma that still haunts Roland.

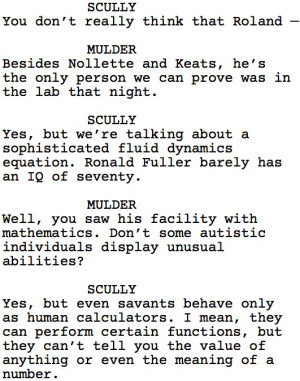

I often find myself railing against the mental-illness-as-superpower trope that seems so prominent in dramas in general. There is an element of that here as Roland is suspected of being the one to have continued Grable’s theoretical work after his death, but in fact an early exchange sees Scully dampen Mulder’s enthusiasm and to dispel such notions in her trademark withering style:

A sensitivity to Roland’s condition is apparent in his compassionate treatment at the hands of his carer, Scully and, in particular, Mulder. This was quite deliberate in terms of the demands of the story, with Nutter commenting:

A sensitivity to Roland’s condition is apparent in his compassionate treatment at the hands of his carer, Scully and, in particular, Mulder. This was quite deliberate in terms of the demands of the story, with Nutter commenting:

We had to create the villain in Roland’s head, so I think the more the audience could relate to Roland and feel and care for him, then it would make the villain that much worse and that much more diabolical.”

In spite of its context to frame the narrative, it is a welcome approach, and it is also complemented by ‘s musical motif for the character, which he described as a “simple, very child-like, slightly forlorn, sad piece”.

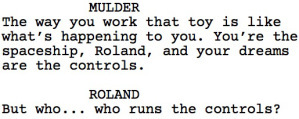

Contrast that sensitivity, however, with the scenes in which Roland carries out the murders he is compelled to undertake, and which make for very uncomfortable viewing. It is always troubling to see those suffering from a mental illness being portrayed as violent, and I balk at these particularly violent deaths that Roland inflicts during the course of the episode, even—or perhaps because—they are revealed to be beyond his control. Ultimately, Roland is presented as a victim himself, a puppet to the powerful whims of his twin’s pervasive consciousness. It is a perspective that Mulder demonstrates via a remote-controlled spaceship during a touching scene in which he seeks to reassure Roland that the violent impulses and premonitions he is experiencing do not make him a bad person:

Yet is it possible here to read the implications from this exchange as being more sinister still? Whilst the implausible explanation for Roland’s behaviour is that he is being psychically controlled by the cryogenically-preserved head of his twin brother, I can’t help but be struck by the allusion that the violent outbursts of this mentally ill man are simply outwith his control. That may be an overstatement and an entirely unintended representation on the part of Ruppenthal’s script. Perhaps the reveal of the X-File at the root of his behaviour is actually meant to subvert such an interpretation. Nonetheless, I find it unsettling.

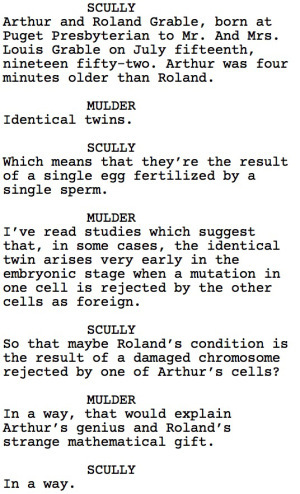

Perhaps the most interesting element of the story is in how it touches upon the genetics of autism. In an exchange between the two agents towards the end of the episode, Mulder suggests that the very existence of the twins may owe to a mutation in their early development in the womb. It is a complex and little-understood topic, but an interesting one to reference under the circumstances, and demonstrates an attempt by Ruppenthal to be authentic in approaching the subject:

There is a certain purity (no pun intended) and even a simplicity to many of the early episodes of The X-Files that I really like. That’s not to draw any unfavourable comparison between the tone or content of earlier versus later episodes; it’s just that, in a sense, the approach feels fresh and unencumbered here, in spite of my reservations. However far the concept at the heart of this instalment pushes the series’ definition of “extreme possibilities” within its purview, something of that purity helps “Roland”. Above all, though, I have to return to the guest performance at its heart, perhaps best summed up by Darren Mooney in his recent review:

Ivanek’s performance feels earnest and sincere. It’s never forced or overplayed, never showy. It has a powerful integrity that lends Roland a dignity that is often lacking in the portrayal of those dealing with these sorts of problems on network television.”

As I noted before in regards to The X-Files, anomalistic psychology can posit mental health and the paranormal as not unnatural bedfellows, when handled respectfully. Ultimately, “Roland” speaks to the potential power of an actor’s performance to help navigate that line with due care, even when the source material itself threatens to veer off course.

May 4, 2015

Banana Episode 6

Title: Banana Episode 6

Writer:

Director:

Network: E4

Original Airdate: 26 February 2015

My favourite piece of television this year to date has been, without a doubt, ‘ Channel 4 series Cucumber: a frank, bold series about modern gay life featuring an ensemble of sharply-drawn, vibrant characters. Its companion anthology series, Banana, which expands the stories of Cucumber‘s peripheral characters in self-contained half-hour instalments, aired on affiliated channel E4 directly after each episode of its parent show.

The series’ sixth instalment follows Amy (played by the episode’s writer, Charlie Covell) who, in early sequences, is established as having a very anxious disposition. Before leaving her perfectly-ordered flat for work, Amy checks and double checks that electrical switches and gas outlets are all turned off. She leaves, gets a few hundred yards up the street… then panics that she’s left the toaster switched on, imagines the entire building burning to the ground, and therefore has to run back to make the same checks all over again.

Once on the bus, she can’t help but insist a fellow commuter ties his shoelaces there and then as she imagines him otherwise tripping into the road after he disembarks. And she only allows herself to accept an offer of a date she receives via a phone app if a woman sat opposite her on the bus looks up before they reach the next stop. Significantly, Amy then spends that time silently willing the woman to look up so that she can do just that. Here is a character whose anxiety leaves her so fearful that she feels unable to exert any personal agency over her day-to-day life.

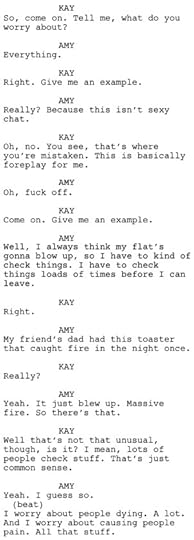

The woman in question looks up in the nick of time, though, and so Amy accepts said date, and subsequently meets Kay (). After a series of false starts thanks to Amy’s social awkwardness and her confession to being “quite weird”, a supportive Kay coaxes Amy to open up about herself over a drink in this gently humorous exchange:

In a behind-the-scenes interview about her involvement in Banana, Covell talks about the nature of the series as well as its potential for a broad appeal:

One thing that Russell and (co-executive producer) were saying when we were talking about stories was that Banana in particular is about (what) they called the ‘hard stare’. So really looking at how people behave and relationships, and the truth in those. So showing ugly and difficult parts of people, and how they interact. All of the stories are set in the LGBT community, but that’s kind of incidental. They’re about people and relationships, and things people have difficulty with: falling in love, or going on a date, or dealing with a horrendous thing happening to you. These aren’t exclusive because they’re all human stories; they’re not exclusive to one group.”

What Covell says here about Banana featuring being human stories that are not exclusive to any one group is equally true of its approach to mental health. Amy’s behaviour might perhaps display signs of what is termed Generalised Anxiety Disorder, but at no stage during the episode is Amy tagged as suffering a mental health condition (to the extent that I feel bad for categorising this entry as I have, and which I do mostly for ease of reference and navigation).

Moreover, the way in which Amy’s behaviour is presented, and the inner voice that Covell portrays so effectively through both her script and performance, jointly serve to humanise and normalise both Amy and her state of mind. The characterisation of Amy achieves the dual success of being at once both very specific and utterly universal. I can personally relate very directly to some of her behavioural quirks. And we live in an anxious age. The Anxiety and Depression Association of America, for example, suggests that anxiety affects up to one fifth of the US population.

Amy’s story comes to its climax as she walks Kay home at the end of their night out—to ensure she arrives safely rather than to be forward—and then agonises over whether or not to kiss her goodnight, willing a light to come on in a building opposite as a “sign” to her that she should do so. Ultimately, Kay seizes the initiative and—in a magical moment—lights start to come on in all the buildings up and down the street. Amy’s willingness to discuss her eccentricities so openly combined with Kay’s open-mindedness have sparked a connection between two people who were strangers just hours earlier. That makes the moment that they finally kiss a triumphant one, and I defy anyone watching not to be left with a warm glow and a sense of life’s possibilities as the credits roll.

All in all, I salute this episode’s ability to present mental health as a normal aspect of our lives that can and should be discussed openly and without judgment. Its efficiency in presenting characters with whom the audience quickly relate, and for whom they will therefore root not in spite of their “quirks” but because of them, is something of a masterclass and characteristic of Cucumber and Banana. Both series are still available to watch in their entirety courtesy of Channel 4’s website as well as via their All 4 catch-up service, plus are available to buy on DVD. And both get my highest recommendation.

February 28, 2015

Star Trek: The Next Generation “Frame of Mind”

Title: Star Trek: The Next Generation “Frame of Mind”

Writer:

Director:

Network: first-run syndication

Original Airdate: 3 May 1993

This month marks the first anniversary for this blog. Across that year of occasional posts on the topic of representations of mental health on the small screen, I have learned much about the subject matter. As a result, I have given a lot of consideration to how I might approach it myself, as was my original intent. And to mark the milestone, I thought it apt to explore the episode that suggested the blog’s title, a stand-out instalment from Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s sixth season.

The episode’s genesis is noteworthy in itself. Working within the time constraints of a network television production schedule, the writers’ room were struggling for story ideas when Brannon Braga posed the simple question, “What if Riker wakes up in an insane asylum?” Three days later, the team had a workable story that was approved to enter production. Braga also cited an interest in surreal imagery, and had the following to say about the episode and his influences:

It was fun for me to do. One of my favourite films is ‘s Repulsion, and I think the influence will show through. I’ve always wanted to write something about someone doubting their sense of reality, and I think it works.

“Frame of Mind” opens with Commander Will Riker () speaking with an unseen figure, seeking to explain that he is of sound mind, that he is ready to leave the confines of his stark surroundings, and then becoming increasingly agitated as he rails against his harsh treatment in a mental health facility wherein he believes he does not belong. As the frame widens, this other figure is revealed to be Data () as it becomes clear that the duo are engaged in rehearsals for a play, presided over by Dr. Beverly Crusher ().

This sense of the audience’s immersion in the layers of Riker’s perception of reality is therefore established within the teaser sequence, and indeed is perpetuated throughout. This perspective shifts between one reality aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise and another as a patient in a mental health hospital on the planet Tilonus IV, which itself comes to parallel scenes in the titular play he has been rehearsing back on the ship. These shifts become ever more abrupt and disturbing as Riker’s hold on reality appears to crumble. A glance at the episode’s preview trailer serves to illustrate the paranoid tone that pervades as a result.

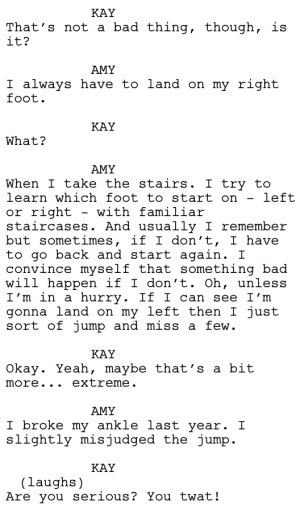

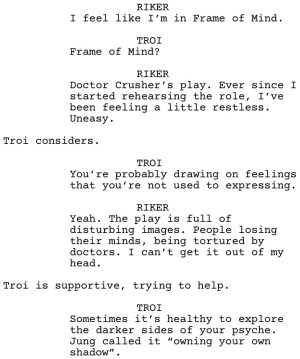

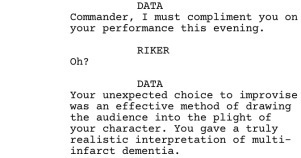

In scenes aboard the Enterprise, Riker seeks the counsel of Deanna Troi (), to whom he confesses his concerns:

Troi is here referring to the shadow aspect of the personality, comprising instinctive and irrational aspects of the self, and suggests that Riker is unsettled by revealing such darker parts of his psyche through his stage role. This opens up some potentially fascinating avenues for Riker’s character development that are ultimately never really explored save during one of the episode’s most effective scenes in which he is subjected to reflection therapy, during which holographic images of Troi, Worf () and Captain Jean-Luc Picard () appear as visual representations of different aspects of that psyche. All we ultimately get from such scenes, however, is a very clear but generic sense that the Enterprise’s second-in-command does not like to be held in circumstances that are outside of his control.

Another throwaway and somewhat comical reference comes from Data reacting to Riker’s unpredictable behaviour during a performance of the titular play:

It is noteworthy that “Frame of Mind” is this blog’s first foray into futuristic science fiction, and therefore its first insight into writers’ vision for the future of mental health, its perception in society, and the potential for its treatment. Perhaps predictably and a little disappointingly, however, this vision very much informed by a contemporary perspective.

The world of Star Trek often made a point of illustrating just how far medical science has advanced in the intervening centuries, with many debilitating illnesses in the twentieth century being readily treated by the twenty-third as depicted in the original Star Trek. The same cannot be said for mental health conditions, though, as represented by the all-too-recognisable scenes within the mental hospital to which Riker is consigned, for example, or in scenes from the play Frame of Mind. Whilst much of the episode’s perspective will be seen to have originated within Riker’s own mind, I am making the assumption here that his visions mirror the world that he inhabits, and therefore are representative of the same.

Again, though, it seems as though this was a deliberate choice on the part of the writer, perhaps necessarily so in order to make Riker’s predicament all the more relatable to the audience. Braga illustrates this in his comments on the choices he made over some of the vernacular used in the script, such as the word “crazy”:

People use this word. it’s a good word, and I decided to use it. When you get too “politically correct’ it shows, and what’s “PC” today won’t be five years from now. Star Trek is a show that transcends time, and we try not to date it.

Ultimately, Riker is revealed to have been captured during his undercover away mission to the planet, and to have been subjected to an invasive procedure designed to extract key strategic information directly from his brain. Most of what is presented in the episode is therefore entirely internal to Riker:

It’s true that both the neurosomatic technique employed by his interrogators in Tilonus IV and Dr. Crusher’s ability to restore Riker’s memory are both signs of advances in neurosurgery—albeit rooted within a contemporary context—but this still feels like an area in which the story lacks a certain vision. Alternatively, perhaps it is deliberately suggestive of a bleak future for the treatment of mental health. Perhaps the episode’s stance posits that more effective treatment for mental health issues will still remain beyond the reaches of medical science in the twenty-fourth century. More likely, though, it represents little thought having been afforded to the potential for this element of the story.

Nonetheless, “Frame of Mind” represents a strong Riker-centric episode and a striking instalment even in the context of what was a a truly remarkable run of high-quality episodes across multiple seasons for Star Trek: The Next Generation. What it may lack in its consideration of the future for mental health treatment it makes up for in the complexity of its set-up and narrative, and in the power of its central performance by Frakes who, in the special features on the Alternate Realities boxset, cites “Frame of Mind” as his favourite Riker episode of the entire series. In accordance with his character’s predicament, it is a story that lingers long in the memory.

January 31, 2015

Monk “Mr. Monk and the Candidate”

Title: Monk “Mr. Monk and the Candidate”

Writer:

Director:

Network: USA Network

Original Airdate: 12 July 2002

To date on the blog I have—quite deliberately—focussed upon series that have resonated with me in some way: in terms of tone, character, content, or some combination thereof. As I approach a second year contemplating this subject of onscreen representations of mental health, I figured it wouldn’t do any harm to broaden my horizons.

And so, for this edition, I consider a series for which I have never had much appreciation. The show itself will be quite indifferent to my opinion, as Monk (2002-09) enjoyed eight popular seasons and earned itself considerable critical acclaim in the process. I won’t be the first person, however, to find fault with the show in terms of its lack of authenticity. (Read no further than a Psychology Today article on a later instalment bluntly headlined, “Why Monk Stunk”.)

Adrian Monk (, who won three Emmys, a Golden Globe, and two Screen Actors Guild award for his performances in the role) is a former San Franciscan detective who lost his badge following a nervous breakdown in the wake of his wife’s death in a car bombing. As a result of the breakdown, the audience is asked to believe that he suffers from no fewer than 312 discrete phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as part of the deep-seated anxiety he now endures.

The series follows Monk returning in an unofficial consulting role to his former homicide unit, somewhat inexplicably given that his former superior, Captain Leland Stottlemeyer () continues to refuse to formally reinstate Monk. This is a quite understandable reaction yet the audience is asked to believe that, due to the extent of Monk’s investigative talents, Stottlemeyer permits him to assist in the capacity of a consultant, overlooking his significant behavioural problems.

Monk falls into one of the classic traps of how mental health conditions are represented as character traits. The implication is that Monk’s brilliance as an investigator is linked to a fastidiousness that is a facet of his OCD: mental illness as superpower. As his often acerbic and incompassionate nurse Sharona Fleming ()—who, rather improbably, gets to accompany him to crime scenes—puts it at one moment during this instalment:

It is accurate to represent phobias as types of anxiety disorder, and also to indicate them as having been caused by trauma, as in Monk’s case, but such phobias tend to be quite specific and related to said trauma. Similarly, OCD can be experienced as a result of a traumatic experience, and therapy such as that which Monk undergoes during this instalment and throughout the series can and does form part of a range of treatment options, but its severity is often trivialised through a focus upon certain types of repetitive behaviours and neatness—in reality just a small subset of the condition’s symptoms.

For me, on the basis of its pilot at least, the series feels like a missed opportunity to explore the deep tragedy and profound grief at the heart of Adrian Monk. The best moments are those of stillness such as when Monk visits his wife’s grave or revisits the parking garage where she died, in which Shalhoub is allowed to eschew farce (his “quirky” graveside serenading by clarinet aside) and contemplate his grief and the limitations placed upon his life by his condition.

Furthermore, in “Mr. Monk and the Candidate” alone, so much of the humour feels inappropriate and in poor taste. Monk’s fear of heights, germs, and—bizarrely—milk are all ridiculed in one way or another, and Sharona often comes across as a particularly unsympathetic character as the medical professional who delivers many of the punchlines:

As it stands, with inconsistent representations of the condition and most scenarios played simply for laughs, I simply cannot accept Monk’s central premise. Imbuing your hero with over three hundred phobias smacks of the show’s format—set up to be a long-running network television series—dictating character, to then be defined at will according to the story-of-the-week.

Clearly, however, this was by design. As series co-creator once commented in terms of the degree to which Monk’s condition was core to the series, “It’s integral. The idea was that a brilliant detective has severe OCD and phobias. That was the pitch. Despite himself, he is able to solve a case every week.” Indeed, during its run, Monk was promoted with the unflattering tagline, “the defective detective”. Similarly so in terms of the choice of tone for the series, which is in effect a modern cozy. For me, however, mental health and comedy make for strange bedfellows when most of your humour is wrought from the suffering a character endures from their condition, or from the ridicule and discrimination they suffer from others as a consequence.

So, if Monk’s creators, producers and writers never set out to present their protagonist as an accurately representative sufferer of a severe anxiety disorder in a serious drama, is it fair to criticise them for the same? Does it matter? Well, I would argue that, at this juncture at least, it absolutely does.

I am put in mind of an interview with Russell T. Davies in the current issue of Attitude magazine, in which he discussed how LGBT characters are cast and written today. (For the record, I feel compelled to be crystal clear that I am not for one moment seeking to draw comparisons between mental health and sexuality, merely drawing some parallels in terms of issues with how these are represented onscreen.) Referring to the casting for his current E4 series, Banana—a companion series to the equally superlative Cucumber on Channel 4—he talks about the obligation he felt to represent the transsexual community, and to do so in as authentic a way as possible:

It was a bit of a change for us to cast a trans actor—it’s debatable: did we have to? I think ten years ago you might not have had to. In ten years time we might not have to. Right now, with the temperature of things as they are—the flavour of things as they are—we had to.

Similarly, I would argue that at this point in time—and, indeed, ten years ago when Monk was at the height of its popularity—the degree and extent of understanding of the reality of OCD and, indeed, many other mental health conditions is still so low that writers have a particular responsibility to be authentic in their portrayals. If, at some point in the future, we reach a stage when mental illness is better understood and widely treated with compassion and empathy, then perhaps we can afford to be more relaxed in terms of how it is used in popular storytelling.

Monk is definitely not to my taste, although I may yet delve into its significant back catalogue again at some point. I should acknowledge in the interests of balance, though, that for all my concerns over its blithe inaccuracies and the myths it perpetuates, some may find comfort and inspiration in the series.

Shalhoub and Hoberman once teamed up with the Anxiety and Depression Association of America to launch an OCD awareness campaign, featuring in public service announcements such as this one. Whilst falling into the common trap of over-identifying with the disorder, Shalhoub said, “What I do with Monk is… uncork the bottle and let everything flow. For a lot of people, there is a fear and embarrassment. But people who suffer with the disorder don’t have to be outcasts. They can be and are contributing members of society.” As the L.A. Times concluded in a 2008 article, “If a guy like Monk can make it through the day, and capture the bad guy to boot, just think what any of us might do.”

December 21, 2014

Northern Exposure “Una Volta in L’Inverno”

Title: Northern Exposure “Una Volta in L’Inverno“

Writer:

Director:

Network: CBS

Original Airdate: 7 March 1994

The winter solstice conjurs memories of one series above all others for me, and hence this seasonal revisit to the unique world of Northern Exposure. There are celebrated episodes that focus either upon the solstice itself (Season Four’s “Northern Lights“) or Christmas (Season Three’s “Seoul Mates“) and which number amongst my personal favourites, but it is “Una Volta in L’Inverno” that suggests itself most strongly for this blog, for reasons that the inimitable Cicely disc jockey Chris Stevens () explains right after the opening credits:

Set against this midwinter backdrop amidst the remoteness of Alaska, the episode features three tales that could all be characterised as A-stories on fairly equal footing, the series having blossomed into a truly ensemble-led show by this, its fifth season. The thread that concerns us centres around hardened trapper Walt Kupfer (), a recurring character by this stage in the series, and his struggles with Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD).

SAD is a very real condition affecting people who live in parts of the world with varying levels of daylight and contrasts in climate, comprising a form of depression indicated (usually, but not exclusively) by reduced exposure to sunlight during the winter. I should note that the causes of SAD are not, however, well understood or clearly established. Nevertheless, whilst we may like to think of ourselves as immune to such effects from our environment they are many and manifest, and can be quite profound.

The choice of Walt as the focal point for this struggle is interesting in and of itself. Here is an older character supposedly used to the long, dark Alaskan winters, resistant to accepting that he is suffering from SAD at all, and having normalised his coping behaviours in previous years. Whilst early scenes see other characters wearing light visors to help combat the lack of natural daylight, Walt is less than impressed as town doctor Joel Fleischman () fits him with his own during a consultation:

Bright light therapy is in fact one of the accepted treatment options for SAD, although some such options come with warnings of an increased risk of skin cancer. (A classic instalment, the aforementioned “Northern Lights”, sees local bar The Brick serve up chocolate with everything on the menu as an alternative way of elevating its customers’ moods.) What Jeff Melvoin—a seasoned writer on the series who contributed some of its very best episodes, and also served as a producer for much of its run—achieves so effectively early in the script is to normalise the condition of SAD, setting Walt apart as a laggard in terms of adopting any means of managing the condition.

Joel’s careful prescription turns out, however, to complicate Walt’s predicament. He takes to the visor a little too well, and over-indulges in its usage. He ignores Marilyn Whirlwind‘s () warnings when he returns to the surgery to seek a replacement bulb, and goes on to cause an accident whilst driving with the visor on. Buoyed by his increased level of mental agility (he even manages to confounds the erudite Chris in a conversation in The Brick, and quotes Shakespeare without a moment’s pause) and renewed physical vigour, he uses the visor virtually non-stop.

Eventually, increasingly concerned by Walt’s dangerous behaviour, and with Joel out of circulation having been stranded in a snowstorm out at Cicely’s airport in one of the episode’s other A-stories, Chris and Holling Vincoeur () have to countenance nothing short of a full intervention:

The script can’t resist adding a touch of Northern Exposure‘s trademark, off-the-wall humour to this exchange, yet there is an element of authenticity to Chris’ story. His comparison between Walt’s behaviour and hypomania is not totally without foundation, given the links between such mania and bipolar disorder, and given that a “seasonal pattern” is sometimes given as a specifier to a diagnosis of bipolar. And this extends, too, to seemingly throwaway details, as Romilar has a proven track record as being prone to abuse as a recreational drug.