Lara Biyuts's Blog, page 3

January 5, 2015

The Last Sipper to Break the Camel’s Back

Published on January 05, 2015 03:10

December 30, 2014

on love

Yalyna’s Night Walk

“Your soul is as a moonlit landscape fair,Peopled with maskers delicate and dim,That play on lutes and dance and have an airOf being sad in their fantastic trim.”(Paul Verlaine. Clair de Lune)

“Tonight, at yours, there are the masks that you invited and the black masks that you did not invite.” (Lara Biyuts)

It was cold last night, and I felt lonely, taking the air in my home town. Now, it was time to go home. The way home took me only twenty minutes, but for some reason I decided to drop in the White Jibber Bar to have a cup of tea. Sitting at a table, immersed in thoughts of my own, I suddenly heard somebody call me. I turned round and there… dear me… a handsome man who I saw never before. Watching me the man smiled in the way that gave me the creeps. I tried to scan him, just in case, if by chance he was a kind of a magician too. Oops… I couldn’t see any bio-field. Then I showed him my nice bare teeth -- thanks heaven, my fangs were not cut in my childhood -- and I winked at him. What came next? When going home, I felt like under a spell, and I heard some footsteps behind. Every time I turned round, nobody was there. Now, at home, coming to the kitchen, I heard the transcendental call again. So pleasant. Ah, I ought to come up to his table. What a lovely adventure it could be! If it went wrong, never mind, for really, nothing to lose.

The End

Lara Biyuts © 2007 https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/505270

http://www.lulu.com/content/16081349

“Your soul is as a moonlit landscape fair,Peopled with maskers delicate and dim,That play on lutes and dance and have an airOf being sad in their fantastic trim.”(Paul Verlaine. Clair de Lune)

“Tonight, at yours, there are the masks that you invited and the black masks that you did not invite.” (Lara Biyuts)

It was cold last night, and I felt lonely, taking the air in my home town. Now, it was time to go home. The way home took me only twenty minutes, but for some reason I decided to drop in the White Jibber Bar to have a cup of tea. Sitting at a table, immersed in thoughts of my own, I suddenly heard somebody call me. I turned round and there… dear me… a handsome man who I saw never before. Watching me the man smiled in the way that gave me the creeps. I tried to scan him, just in case, if by chance he was a kind of a magician too. Oops… I couldn’t see any bio-field. Then I showed him my nice bare teeth -- thanks heaven, my fangs were not cut in my childhood -- and I winked at him. What came next? When going home, I felt like under a spell, and I heard some footsteps behind. Every time I turned round, nobody was there. Now, at home, coming to the kitchen, I heard the transcendental call again. So pleasant. Ah, I ought to come up to his table. What a lovely adventure it could be! If it went wrong, never mind, for really, nothing to lose.

The End

Lara Biyuts © 2007 https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/505270

http://www.lulu.com/content/16081349

Published on December 30, 2014 00:18

November 27, 2014

Meet the new stylish model

Susan Chettri is currently living in Nepal, doing modeling in Kathmandu. By now, he has done TV and paper ads as well as filming, for his aim Hollywood, that’s why the young model needs help in promotion.

A medical worker by trade, Susan Chettri wants to show his other talents to the world.

With love from Kathmandu, Nepal.

Published on November 27, 2014 02:17

July 4, 2014

Of Words and Water 2014

Download the new FREE eBook of short stories and poems from an international group of authors: Of Words and Water 2014https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/452447I am one of the contributors. Thank you all for your support.

Questionnaire

1. What inspired you to contribute to the anthology?

One day, on Goodreads, I saw a message by Jay Howard, Author and Editor, about the anthology. It sounded inspiring so much. 2. Rain, snow, or ice? Why?

Snow. Rainy weather never could spoil my day or prevent me from enjoying life, and I always loved our Russian snow. When I was young, I loved winter more than summertime. But today, I hate winters, because the homeless and stray animals feel so cold in our cold northern winters.

3. Can you tell us a little bit about your story?

My poem “Snowfall” is my musing about an instant of life, about the beautiful, and it’s my view of Symbolism in literature.

Published on July 04, 2014 05:45

February 6, 2014

February

5 February, marks the official first day of spring in the ancient Roman calendar – and renewal; renewal of agricultural pursuits, a purging of previous errors, omissions and mistakes, and cleaning karmic slates to start the New Year fresh. Dies natalis was also observed today on the Capitoline Hill in the Temple of Concordia.

Parentalia, the essence of expiation and rebirth, begins on the ides – Thursday, 13 February, with a Vestal officiating at the Tomb of Tarpeia, and concluding on Friday, 21 February, with Feralia—midnight rituals. Bookended between these two state-sponsored observances, Parentalia was very much a private, family affair – with the paterfamilias honoring the family Lares and household gods. Garlands of flowers, gifts of wheat, bread and wine – communal meals inviting the honored dead were held at homes, holy sites and ancestral tombs, to acknowledge the invisible but very real ancestral bonds that survive death. Lupercalia - on the 15th of February provided a break from appeasing the benevolent ancestral dead, with public fertility rituals (In case the renewed communion with the spirit world raised any unintended consequences, rubbing the body all over with puppies would calm things down).

As the end of Paternalia approached, the duties of the paterfamilias became darker, and the ceremonies increasingly focus on appeasing, placating and even exorcising the more malevolent aspects of his Manes. On the 21st, Feralia demanded dark rites placating the di inferni gods below.

Caristia or Cara Cognatio, on 22 February, allowed for cleansing rituals, and a family feast celebrating love, reconciliation and forgiveness. Friends who became alienated during the previous year would reunite and forgive offenses, real or imagined.

Terminalia, on Sunday, 23 February allows the city to enter the new year purified, and concentrate on the affairs of the living.

24 Feb Regifugium (the Flight of the King) – commemorated the end of monarchy and birth of the Republic (a final cleansing ceremony – of sorts).

Source:

https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/antonine_imperium/info

Source: this writer and Revue Blanche

Parentalia, the essence of expiation and rebirth, begins on the ides – Thursday, 13 February, with a Vestal officiating at the Tomb of Tarpeia, and concluding on Friday, 21 February, with Feralia—midnight rituals. Bookended between these two state-sponsored observances, Parentalia was very much a private, family affair – with the paterfamilias honoring the family Lares and household gods. Garlands of flowers, gifts of wheat, bread and wine – communal meals inviting the honored dead were held at homes, holy sites and ancestral tombs, to acknowledge the invisible but very real ancestral bonds that survive death. Lupercalia - on the 15th of February provided a break from appeasing the benevolent ancestral dead, with public fertility rituals (In case the renewed communion with the spirit world raised any unintended consequences, rubbing the body all over with puppies would calm things down).

As the end of Paternalia approached, the duties of the paterfamilias became darker, and the ceremonies increasingly focus on appeasing, placating and even exorcising the more malevolent aspects of his Manes. On the 21st, Feralia demanded dark rites placating the di inferni gods below.

Caristia or Cara Cognatio, on 22 February, allowed for cleansing rituals, and a family feast celebrating love, reconciliation and forgiveness. Friends who became alienated during the previous year would reunite and forgive offenses, real or imagined.

Terminalia, on Sunday, 23 February allows the city to enter the new year purified, and concentrate on the affairs of the living.

24 Feb Regifugium (the Flight of the King) – commemorated the end of monarchy and birth of the Republic (a final cleansing ceremony – of sorts).

Source:

https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/antonine_imperium/info

Source: this writer and Revue Blanche

Published on February 06, 2014 00:07

January 27, 2014

logos

Published on January 27, 2014 01:18

December 8, 2013

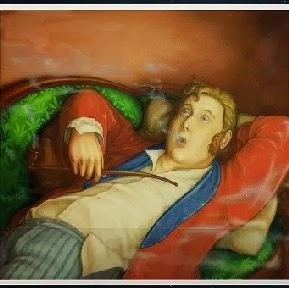

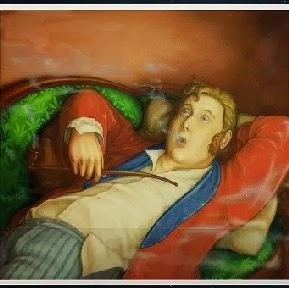

android obesity

Introduction

“Of Human Bondage”. This essay is an excerpt in my historical “Through the Baltic Looking-Glass”, Part 6. Reading it, please, keep in mind that the notes are written in 1912 (that is,101 years before the historical was designed by the author and cyber-mentioned in 2011). Place: the Russian Empire. Narrator: an observant glob-trotter and autocar-hater of the name of Oscar Maria Graf. The main personage of my latest historical, he is a second-self of my novel’s main personage (whose writings is the historical), and not mine. (A novel inside another).

Of Human Bondage

Among human vices, there is the only that suggests much good about its bearer, in case if the human is not too ugly, not looking like an oaf. I’m talking of sloth, and the remembrance of my prodigious elder contemporary Oscar Wilde made me launch into this digression on Sloth, one of the deadly sins. Laziness. Idleness. “Idleness is the root of all evil.” I believe not. Scarcely offsprings like Thievery and Cruelty could come from this particular root. To steal, in the literary sense of the word, in other words, to get into somebody else’s apartments through small casements or chimney, to jump from a crowded horse-drawn tram on the move with somebody else’s purse in hand and to spend hours walking up and down the back staircases in search of a proper doorway, Man should have an exceptional capacity for work. A mere cruelty demands much effort. An intention to do a nasty trick to anybody demands special knowledge, long walk for elaborating a plan of the nasty trick, innumerable phone calls, typewriting denunciations, and visits, after all, in the fifth and sixth floors of buildings with no lift. A salesman of match factory is equal to the task rather than lazybones.

I love the kind of sloth, which is low-key like our fine ear for music and eternal as birthmark, and Man even takes pride in it at heart. Blossoming in Oblomovist’s infancy, the Sloth is flowering for the rest of his life. Lazybones, idlers and other sluggards, I’ll call them “Oblomovists” in this digression, the renowned proponent or archetype of Oblomovism. A “lazy, apathetic person.” Apropos, as my reader knows, Oblomov was good-looking and of noble birth, that’s why my remark about a look of an oaf.

It’s interesting to watch Oblomovosts. When Oblomovist subsides in a chair, in public, his eyes and every fold of his coat tells about a mental monologue like this: “Why do you badger me, all of you? Do I disturb anyone? Leave me alone, please…” He dreams about especially big flypaper, at his room door, for strangers as well as his friends.

Oblomovists are exceptionally constant in affairs of the heart. A love affair is a labour, one of hardest, sometimes, and however fast the scud of centuries, however strong time subjugates all to the capitalist system, nobody ever hit upon an idea of a fair division of labour in this ticklish sphere, inventing a conveyer, at least, like those at a small cannery. One cuts a sardine’s head, another throws it to oil, the thirds prepares a tin, and so on, till the label is attached and the tinned sardines are ready for usage. At a love’s labour, one has to do everything by himself. If there was a “division of labour” in it, the last in the process, the one who attached a label, could be a man who elopes with somebody else’s bride three months after the wedding. Oblomovist falls in love only three times in his lifetime, that’s why he’s called a one-woman man. For the first time, aged 12, he falls in love out of lack of experience; for the second time, aged 18, he falls in love out of solidarity with his palls in love. If he ever falls in love again, he does it at 30 to 40, and it’s his third and final time, which destines him to a lamentable end: he brings a young entity into his home, with him peering into the future in state of a special meek fear and quiet passivity usual for some heroines of Greek tragedies and heroes of Shakespeare at the moments of their temporary weakness or hesitation. Too sublime to be described. And then, the Oblomovist falls in love never again. His first romantic experience introduces him to the tormenting sense of the unshared love with the loud glee and intense curiosity from everybody: friends, relatives, strangers and eyewitnesses. His the second time, he enjoys the shared love with all its tormenting appendages: leaving home, the duty to wait at the box office, outpourings to his beloved one’s relatives, and defence of her virtues before his own relatives. All this is for better to obese men, who feel determined to lose some weight by means of sudden shocks and long-distance races. For the Oblomovist, all this is but a burden. In the course of his third and final love affair, it’s clear to him that Love looks much like those registration forms, in which Man must put his name, surname, and a few formalities more – address, or something. With knowledge like this, Oblomovist cannot become disloyal. In his view, adultery is a ghastly bill, which must be paid with his own blood and flesh:

(1) the first acquaintance – two encounters at their friends’ (the horse-drawn tram, the seventh floor, the four-hour talk), the box, and care of it;

(2) developing the acquaintance -- his invention of a special meetings for his wife, a place for rendezvous;

(3) terms of intimacy – supper at restaurant and taking home (the overdone hazel-grouses, tainted caviar, his return home at 4 a.m., and the long taking off his boots at the door);

(4) tender passion – his search for cheap brooches and hurried stopping rumors, scenes at home, his wife’s strange and alarming look and behavior;

(5) coolness before parting -- the encounter with his old friend Stolz and his week-long thinking over Stolz’ tone when both of them were at his beloved woman’s drawing-room;

(6) “let’s forget each other!” -- his prompt and cheerful doing his wife’s small commissions (cleaning gloves, browsing lampshades, search for an inexpensive dressmaker) for the sake of quietude at home.

Present this bill (above) to Oblomovist at the moments, when he is about to know a good-looking woman better, and he repels it with a plaintive cry of a tormented soul and puts the image of the good-looking woman out of his head for ever. In case if he doesn’t repel the bill, then he is not Oblomovist but a tailor’s apprentice with curved legs and everlasting care about new commissions beyond his strength.

The most of Oblomovists are wise men, because they have plenty of time for thinking over anything occurs him.

A man of expansive nature usually thinks over his action a long while after he did it. “You know,” the man says, “I shouldn’t call Dermott swine… Especially, in public, and to his face. It appears, he never wrote that letter…” or he simply runs about the room, grabbing every thing on his way, and eventually finding a harbour for his hands – his own head – he begins pulling at it, and crying out: “What an idiot I am!.. I’m stupid… stupid!.. The embezzlement! Why did I do it?!.. Grabbed the money, lost it, lied that I spent the day at work, and as a result, spent the night at the porter’s…”

Oblomovist, on the contrary, ponders all, even what he is not about to do. Being too late to a theater show, when lying on his divan, he imagines how many small misfortunes he could get from his four-hour observance of somebody else’s pretence, pretentiousness, stupidity and vanity, and he rises from the divan with relish, which is much more intensive than that in case of his return home after the theatre show. As a result: the reasonable economizing and the chance to go to bed earlier tonight.

Every Oblomovist is prepared for all vagaries of life, because at leisure he has thought over everything – an unexpected and enormous legacy, hard to be calculated even by the best accountants of St Petersburg, and a sluggard rapidly turning into a French aviator, and an unexpected collapse of a building with the ground would swallowing it up – everything, right up to a need to grow big blue wings for flying from one housetop to another.

Every Oblomovist is always an excellent reader. Every author’s dream reader. Taking a book in hands, he elicits all what the author and publisher wanted to give for one ruble and a half, unlike the other readers. Take as an example an active, hard-working man, who uses fifteen kopeks at most of a three-ruble book. Learning of the main character’s name and the fortune of the main character’s father, and learning from the last page of a place of the main character’s last rest place, the active reader lightheartedly goes out for personal reasons. Why do men like that read fiction? Books for them should be written by beat policemen and not by men of letters: certificate of birth fist, then certificates of graduation from school, compulsory vaccinations and previous convictions, and finally, the properly signed death certificate. Oblomovist reads every book with great relish. He realises that after he reads it through, he has to start another work. As the very thought of a new work is hateful as such, he rereads the book till he feels certain that the author keeps from him nothing of the underlying theme and no one word.

However, there are hours, even days, when Oblomovists get active and mobile. Auto-mobile. It’s the time when he goes to rent an apartment, for really, our accommodation along with every component is a vital base for our Sloth.

An active, hard-working man is quick looking for an accommodation and he doesn’t waste time taking it. “What, my divan cannot be placed here? And I’ll place it in the next room. A draught here, you say? When? Always?.. Well, that’s odd!.. However, I’m always busy. I simply have no time to watch draughts… The window is too small, you say? And I’ll place it in… I cannot?.. Never mind. Who could I bid a bargain here?”

Oblomovist is observant and thrifty: “If I want to open the window, I’ll have to stand up, go round the table and remove the armchair… You seem to offer me a penal servitude with the two-year contract and not an apartment. 50 rubles for six rooms with firewood? Happiness is not in firewood. Where will I place my divan? Here?! Do you believe one of my hands is two-meter long?.. To stand up every time I need a cigarette and to go to the table?.. God forbid! Sorry to disturb you.” However, if he rents an apartment, he insists on his arrival before his furniture is brought there. He sits down on a windowsill and patiently waits till the apartment is furnished and completely prepared for living.

Oblomovists are gentle. A human’s heart can be hardened and soul embittered by meetings, talks, intrigues, mingling in society. While contemplating life in the silence of his study, Oblomovist is protected from all the factors of emotional and moral bitterness.

Oblomovist readily listens to outpourings from an enamoured person, because the person is in need of verbal response alone, and Oblomovist may not rise from his chair to give it, with other cases known when a man, merely hurting his leg against a cab, insists on his listener’s kneeling and careful examination of a big blear blot of a bruise over his bared, pale and hairy leg – fancy that!

Oblomovist loves talking of flowers, springtime and beauty of sunrises, because nobody ever had thought of arguing on the indisputable subjects and he may not stand up to take an encyclopedia in hands and dig for several articles in the heavy volume, humiliating both himself and the encyclopaedia, which as though was made to maintain somebody’s ignorance and shallowness. Generally speaking, one should not ever start arguing. Especially, about some important and burning issues that demand meditations. If your companion is a learned and respected man, you should not think that he could get resolved on changing his all views after your fifth sentence. If your companion is a youngster, who argues solely in virtue of his pubertal age, it’s ridiculous to pretend a house of reformation and improve young minds. Oblomovists never start arguing.

I like their look and manner, and I’m often nice to them -- not those who have big flabby paunches and eyes closed with fat, and who can get exited only at table when anticipating the third remove – no, others, those, who even work, from time to time, or always bear burden of career and vanity, and who always have the same dream shining between their eyelids and vibrating in their hearts: “Ah! If only I could leave all! To drive everybody away, to take a seat and to have a rest for two or three years… in order to do nothing socially useful or of public utility!..” When I see men with the unrealizable dream in eyes, I feel sad. Maybe, because I myself would like to live, doing nothing socially useful from a utilitarian point of view. Why? Because I am one of them, most likely.

(the end of the excerpt)

Lara Biyuts ©

“Of Human Bondage”. This essay is an excerpt in my historical “Through the Baltic Looking-Glass”, Part 6. Reading it, please, keep in mind that the notes are written in 1912 (that is,101 years before the historical was designed by the author and cyber-mentioned in 2011). Place: the Russian Empire. Narrator: an observant glob-trotter and autocar-hater of the name of Oscar Maria Graf. The main personage of my latest historical, he is a second-self of my novel’s main personage (whose writings is the historical), and not mine. (A novel inside another).

Of Human Bondage

Among human vices, there is the only that suggests much good about its bearer, in case if the human is not too ugly, not looking like an oaf. I’m talking of sloth, and the remembrance of my prodigious elder contemporary Oscar Wilde made me launch into this digression on Sloth, one of the deadly sins. Laziness. Idleness. “Idleness is the root of all evil.” I believe not. Scarcely offsprings like Thievery and Cruelty could come from this particular root. To steal, in the literary sense of the word, in other words, to get into somebody else’s apartments through small casements or chimney, to jump from a crowded horse-drawn tram on the move with somebody else’s purse in hand and to spend hours walking up and down the back staircases in search of a proper doorway, Man should have an exceptional capacity for work. A mere cruelty demands much effort. An intention to do a nasty trick to anybody demands special knowledge, long walk for elaborating a plan of the nasty trick, innumerable phone calls, typewriting denunciations, and visits, after all, in the fifth and sixth floors of buildings with no lift. A salesman of match factory is equal to the task rather than lazybones.

I love the kind of sloth, which is low-key like our fine ear for music and eternal as birthmark, and Man even takes pride in it at heart. Blossoming in Oblomovist’s infancy, the Sloth is flowering for the rest of his life. Lazybones, idlers and other sluggards, I’ll call them “Oblomovists” in this digression, the renowned proponent or archetype of Oblomovism. A “lazy, apathetic person.” Apropos, as my reader knows, Oblomov was good-looking and of noble birth, that’s why my remark about a look of an oaf.

It’s interesting to watch Oblomovosts. When Oblomovist subsides in a chair, in public, his eyes and every fold of his coat tells about a mental monologue like this: “Why do you badger me, all of you? Do I disturb anyone? Leave me alone, please…” He dreams about especially big flypaper, at his room door, for strangers as well as his friends.

Oblomovists are exceptionally constant in affairs of the heart. A love affair is a labour, one of hardest, sometimes, and however fast the scud of centuries, however strong time subjugates all to the capitalist system, nobody ever hit upon an idea of a fair division of labour in this ticklish sphere, inventing a conveyer, at least, like those at a small cannery. One cuts a sardine’s head, another throws it to oil, the thirds prepares a tin, and so on, till the label is attached and the tinned sardines are ready for usage. At a love’s labour, one has to do everything by himself. If there was a “division of labour” in it, the last in the process, the one who attached a label, could be a man who elopes with somebody else’s bride three months after the wedding. Oblomovist falls in love only three times in his lifetime, that’s why he’s called a one-woman man. For the first time, aged 12, he falls in love out of lack of experience; for the second time, aged 18, he falls in love out of solidarity with his palls in love. If he ever falls in love again, he does it at 30 to 40, and it’s his third and final time, which destines him to a lamentable end: he brings a young entity into his home, with him peering into the future in state of a special meek fear and quiet passivity usual for some heroines of Greek tragedies and heroes of Shakespeare at the moments of their temporary weakness or hesitation. Too sublime to be described. And then, the Oblomovist falls in love never again. His first romantic experience introduces him to the tormenting sense of the unshared love with the loud glee and intense curiosity from everybody: friends, relatives, strangers and eyewitnesses. His the second time, he enjoys the shared love with all its tormenting appendages: leaving home, the duty to wait at the box office, outpourings to his beloved one’s relatives, and defence of her virtues before his own relatives. All this is for better to obese men, who feel determined to lose some weight by means of sudden shocks and long-distance races. For the Oblomovist, all this is but a burden. In the course of his third and final love affair, it’s clear to him that Love looks much like those registration forms, in which Man must put his name, surname, and a few formalities more – address, or something. With knowledge like this, Oblomovist cannot become disloyal. In his view, adultery is a ghastly bill, which must be paid with his own blood and flesh:

(1) the first acquaintance – two encounters at their friends’ (the horse-drawn tram, the seventh floor, the four-hour talk), the box, and care of it;

(2) developing the acquaintance -- his invention of a special meetings for his wife, a place for rendezvous;

(3) terms of intimacy – supper at restaurant and taking home (the overdone hazel-grouses, tainted caviar, his return home at 4 a.m., and the long taking off his boots at the door);

(4) tender passion – his search for cheap brooches and hurried stopping rumors, scenes at home, his wife’s strange and alarming look and behavior;

(5) coolness before parting -- the encounter with his old friend Stolz and his week-long thinking over Stolz’ tone when both of them were at his beloved woman’s drawing-room;

(6) “let’s forget each other!” -- his prompt and cheerful doing his wife’s small commissions (cleaning gloves, browsing lampshades, search for an inexpensive dressmaker) for the sake of quietude at home.

Present this bill (above) to Oblomovist at the moments, when he is about to know a good-looking woman better, and he repels it with a plaintive cry of a tormented soul and puts the image of the good-looking woman out of his head for ever. In case if he doesn’t repel the bill, then he is not Oblomovist but a tailor’s apprentice with curved legs and everlasting care about new commissions beyond his strength.

The most of Oblomovists are wise men, because they have plenty of time for thinking over anything occurs him.

A man of expansive nature usually thinks over his action a long while after he did it. “You know,” the man says, “I shouldn’t call Dermott swine… Especially, in public, and to his face. It appears, he never wrote that letter…” or he simply runs about the room, grabbing every thing on his way, and eventually finding a harbour for his hands – his own head – he begins pulling at it, and crying out: “What an idiot I am!.. I’m stupid… stupid!.. The embezzlement! Why did I do it?!.. Grabbed the money, lost it, lied that I spent the day at work, and as a result, spent the night at the porter’s…”

Oblomovist, on the contrary, ponders all, even what he is not about to do. Being too late to a theater show, when lying on his divan, he imagines how many small misfortunes he could get from his four-hour observance of somebody else’s pretence, pretentiousness, stupidity and vanity, and he rises from the divan with relish, which is much more intensive than that in case of his return home after the theatre show. As a result: the reasonable economizing and the chance to go to bed earlier tonight.

Every Oblomovist is prepared for all vagaries of life, because at leisure he has thought over everything – an unexpected and enormous legacy, hard to be calculated even by the best accountants of St Petersburg, and a sluggard rapidly turning into a French aviator, and an unexpected collapse of a building with the ground would swallowing it up – everything, right up to a need to grow big blue wings for flying from one housetop to another.

Every Oblomovist is always an excellent reader. Every author’s dream reader. Taking a book in hands, he elicits all what the author and publisher wanted to give for one ruble and a half, unlike the other readers. Take as an example an active, hard-working man, who uses fifteen kopeks at most of a three-ruble book. Learning of the main character’s name and the fortune of the main character’s father, and learning from the last page of a place of the main character’s last rest place, the active reader lightheartedly goes out for personal reasons. Why do men like that read fiction? Books for them should be written by beat policemen and not by men of letters: certificate of birth fist, then certificates of graduation from school, compulsory vaccinations and previous convictions, and finally, the properly signed death certificate. Oblomovist reads every book with great relish. He realises that after he reads it through, he has to start another work. As the very thought of a new work is hateful as such, he rereads the book till he feels certain that the author keeps from him nothing of the underlying theme and no one word.

However, there are hours, even days, when Oblomovists get active and mobile. Auto-mobile. It’s the time when he goes to rent an apartment, for really, our accommodation along with every component is a vital base for our Sloth.

An active, hard-working man is quick looking for an accommodation and he doesn’t waste time taking it. “What, my divan cannot be placed here? And I’ll place it in the next room. A draught here, you say? When? Always?.. Well, that’s odd!.. However, I’m always busy. I simply have no time to watch draughts… The window is too small, you say? And I’ll place it in… I cannot?.. Never mind. Who could I bid a bargain here?”

Oblomovist is observant and thrifty: “If I want to open the window, I’ll have to stand up, go round the table and remove the armchair… You seem to offer me a penal servitude with the two-year contract and not an apartment. 50 rubles for six rooms with firewood? Happiness is not in firewood. Where will I place my divan? Here?! Do you believe one of my hands is two-meter long?.. To stand up every time I need a cigarette and to go to the table?.. God forbid! Sorry to disturb you.” However, if he rents an apartment, he insists on his arrival before his furniture is brought there. He sits down on a windowsill and patiently waits till the apartment is furnished and completely prepared for living.

Oblomovists are gentle. A human’s heart can be hardened and soul embittered by meetings, talks, intrigues, mingling in society. While contemplating life in the silence of his study, Oblomovist is protected from all the factors of emotional and moral bitterness.

Oblomovist readily listens to outpourings from an enamoured person, because the person is in need of verbal response alone, and Oblomovist may not rise from his chair to give it, with other cases known when a man, merely hurting his leg against a cab, insists on his listener’s kneeling and careful examination of a big blear blot of a bruise over his bared, pale and hairy leg – fancy that!

Oblomovist loves talking of flowers, springtime and beauty of sunrises, because nobody ever had thought of arguing on the indisputable subjects and he may not stand up to take an encyclopedia in hands and dig for several articles in the heavy volume, humiliating both himself and the encyclopaedia, which as though was made to maintain somebody’s ignorance and shallowness. Generally speaking, one should not ever start arguing. Especially, about some important and burning issues that demand meditations. If your companion is a learned and respected man, you should not think that he could get resolved on changing his all views after your fifth sentence. If your companion is a youngster, who argues solely in virtue of his pubertal age, it’s ridiculous to pretend a house of reformation and improve young minds. Oblomovists never start arguing.

I like their look and manner, and I’m often nice to them -- not those who have big flabby paunches and eyes closed with fat, and who can get exited only at table when anticipating the third remove – no, others, those, who even work, from time to time, or always bear burden of career and vanity, and who always have the same dream shining between their eyelids and vibrating in their hearts: “Ah! If only I could leave all! To drive everybody away, to take a seat and to have a rest for two or three years… in order to do nothing socially useful or of public utility!..” When I see men with the unrealizable dream in eyes, I feel sad. Maybe, because I myself would like to live, doing nothing socially useful from a utilitarian point of view. Why? Because I am one of them, most likely.

(the end of the excerpt)

Lara Biyuts ©

Published on December 08, 2013 06:39

August 27, 2013

diapason

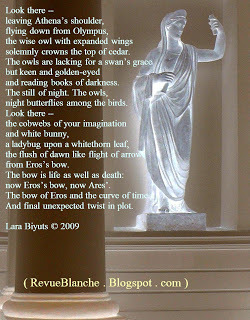

Kythera

Born twice, first among the waves, then in the clouds; here not to work, not to toil in the hot sun, no, to be caught the toils of pleasures, at most. The family-tree is obscure, no metrics, only metricians. “Daughter of regiment”, the plebes would say, and esoterics would say, “Strange conjuncture of planets”. My name is a gift from Ephes. Apuleius would stung me by his “Golden Ass”, me, equal to Isis and Ishtar. Blood of Uranus rages in my veins; Kronos gave up when trying to reach me. Acknowledged as daughter by Zeus, who used to be Lord to humans, charites and nymphs--I’m among them, so young and taciturn. What’s in words to a tender passion? Young Paris surrenders, Helene surrenders. The sun-kissed isles are burning. Pathos is oozing, Lesbos has gone mad, Pasiphae and Mira are captured, and I am myself a mother of Eros the infant, with matrimonial fidelity dubious and at stake. Rejected again, for the fifth time, impassionate, ghastly, Poseidon is beating against the rocks and drowning the ships. Anchis, Ares, Adonis, Hephaestus, at cetera. The arrows of Eros have reached many hearts. To Gods, I was always temptation. To mortals, I brought ambrosia, nectar. To those who turned a deaf ear to tread of mine, to those who rejected my gifts--my punishment, oblivion. Young Hippolytus was wrong... Where I am, today? What’s in words to the oblivion? What about my dreams and desires? Maybe, I walk over some wilted meadows of seashore, maybe, along the water edge, listening to the waves, attracted by me and bringing Hellas to my feet. Lara Biyuts © 2013

Next time, I’ll try to verse about the god Eros :)

P. S.

I used Grammarly to grammar check this post, because... time spent proofreading could be time spent writing!

Lara Biyuts

Published on August 27, 2013 02:05

July 16, 2013

twice told tale

The Balloon Ascension

It began quite unexpectedly. Time: the 1900s. Place: St Petersburg, the Russian Empire. One day, at a soiree, Grigori Rasputin mingled in society. Surrounded by ladies of society, he confusedly wheezed and poked at a slice of pineapple with his big dirty finer. “Something magic is in you,” one of the ladies nodded at him gently, “Irresistible appeal. You are a mystic.” Believing that the lady’s meaning was his former business, horsestealing,in Tobolsk of the time, when nobody was about to remember his patronymic name, Rasputin began shuffling out, “Bosh! It’s all fibs. Mikhail stole, and I didn’t. Our village constable tells untruth.” “No, no! Don’t argue, Grigori Yefimovich!” all the ladies began vividly protesting, “You are a sphinx. An enigmatic sphinx.” “Maybe, I am, gals,” Rasputin agreed, ready for paltering, “but if you talk about Ivan’s gelding, then you are wrong to think that. True, someone stole, but someone didn’t. Actually, that’s a thing of the past. Nothing worth remembering.” “Gelding. It sounds beautiful,” one of the ladies whispered to her friend, “Something dimly attractive. If my newborn is boy, I shall name him Gelding. Gelding Pavlovich.” Next, at the soiree, Rasputin was called “versatile,” “huge,” “unearthly,” “empyrean.” More and more anxious, he glanced at the doorway, from time to time, thinking to himself, “All the women are bigwigs. Their husbands may be police officers. Now, they worry me with their words, and soon, they can get to the truth. If they call their husbands, then give up, you phony old bogus man Grigori…” Aloud, he said, “So... Imust be off.”“No, no! We won’t let you go!” the ladies got agitated, “Not at any price!”“This is it!” Rasputin got frightened, “I’m caught like a sparrow!” he thought, “I must do a trick to be taken away and get out of here… To get out of here, at all costs...” He reached for a big crystal vase and pulled at the edge of the tablecloth, but a prompt valet replaced the vase on another table. “At all costs, but not the vase,” Rasputin thought, “For a huge vase like this, I’ll be beaten. And then go, Grigori, live with no ribs.” But the Siberian’s quick wits suggested him a brilliant way out. Pausing at the doorway, he beckoned the hostess of the Salon to approach and then he said to her, “Get ready, old woman. We are going to the bathhouse.” With that, the splendid Ascension of Grigori Rasputin began. It seemed to him that a moment more and he would hear shouts of the indignant guests addressing to him, his cheek got reddened beforehand with a blow, and he thrilled with anticipation of the moment when he could find a point of rest again among the cold cobblestones of the street pavement, and free again, he could dash to his humble abode... But something unexpected ensued. “To the bathhouse?” the hostess said, “Just a moment, Grigori Yefimovich...” When the hostess and he left, going to the entry, he could hear the envious whispers from the hall, “…lucky… lucky… she’s so lucky…” When they got into her carriage, her old valet turned to her to ask, “So, Madame, I was told to say it to Count?” “Yes,” she said, “Say exactly, to the bathhouse. To get purified of sins. Tell my husband he has nothing to worry about. I’ll get purified and then return home.”3 months passed from the day of the soiree. Ladies of society proved to be wallowed in sin to such an extent that the purification of their sins never stopped even on Twelve Great Feasts. Families and generations came to get the purification. Old grannies led their young granddaughters. Rasputin’s fame rose. “A lady is here,” his cook would announce, “May she come in?” “What does she want?” Rasputin looked displeased. “She says she has free time from five to seven today, so, she says, she’s in a hurry, for her motorcar’s waiting outside.” “What does she look like?” “She’s old, fat and her complexion is muddy and spotty.” “Drive her away. Tell her she’s sinless. Tell her she should sin, first, and only then come to me.” Then his clients began making appointments with him. But no, it never helped to please him. Rasputin wanted exceptional clients, and one day, he severely talked to one Baroness, who received his purification, “Look, Polly, I want to get to the highest spheres. Take me where there are the highest.” As Rasputin threatened to go on strike, he was taken there and got what he asked.First seeing a civil general, he got timid. “Are you a police officer, by any chance?” he asked, showing his diplomacy.“Higher,” the General barked out.“Well… well…” Rasputin moved aside, but he paused. Those, who had known the way to humans’ trust, could not leave the way, and Rasputin resorted to the help of the manner which had made his career success. He beckoned the General to approach and then he said, “Let’s go to the bathhouse!”The General was not about to go, but this proposal was so unexpected for society that Rasputin got widely reputed as an exceptionally eccentric person. In 2 days of stay in the highest spheres, Rasputin was in need of two rubles to buy fresh foot wrap rags. He tried to ask the door-keeper of the house where he lived, but he was refused, because the door-keeper alleged the high cost of living, regardless of the requester’s splendid career.Refused, the requester said, “You’ll be choked with your two rubles, soon.” Rasputin simply voiced his sudden wish. “Well that’s odd!” the door-keeper said, “Did a voice say to you that I can be choked with anything?” “A voice?” Rasputin said, and then he grabbed the door-keeper’s hand, “You saved me, my dove, saved!..” In 3 minutes, Rasputin was standing before eyes of a curvaceous and laced in lady, peering at her face and dully dictating his will, “I heard a Voice, Natasha… It said: go to her and tell her to give you three rubles.” “A Voice?” the lady humbly looked up at him. “A Voice.” “Three rubles? You are not mistaken? Maybe, more, Grigori Yefimovich?” The lady was highly surprised by the moderateness of the Inner Voice.“You are right,” Rasputin lowered his voice to prophetic, “It was two voices. One said: ask three rubles, and another said: ask seven and a half.” Beginning from the day, the mystique Voice had possessed Rasputin completely, and it worried him a daylong. “Anything wrong with you, Grigori Yefimovich?” “Quite so, brother. The Voice. I’ve heard it but just. It said that the fist comer should buy me two bottles of cognac, and a pair of new boots should be sent to my address.”“May I send all this to your address in Gorochovaia Street?”“You may send all this to anywhere, brother. Donation is donation wherever it’s sent.”The weird Voice proved to be mighty, able to shuffle funds among various accounts, and it was quick to improve Rasputin’s well-being. Every night it demanded from Rasputin’s friends something new for Grigori Yefimovich, various things, from a new accordion to 30 000 rubles in gold on his bank account. It’s the opening chapter of Rasputin’s career. The ending has been lavishly described. My essay is but Introduction.

The End

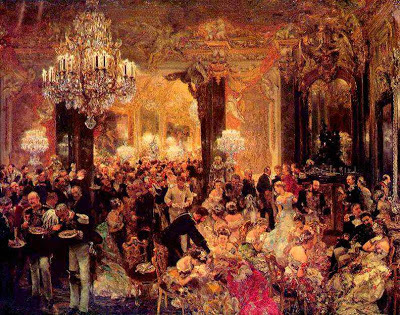

P. S.However I hate Russia, ignorance I hate much more, and if someone betrays ignorance about some facts, I’ll never say it’s all right. But the essay (above) is only a fiction, a fantasy on the theme. Artist: Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel (1815-1905). Thank you for viewing.

L. B.

Published on July 16, 2013 08:52

May 29, 2013

Mikhail Lermontov

dedicated to the only poem:

Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841). Cradle Song Of The Cossack Mother

Slumber sweet, my fairest baby,

Slumber calmly, sleep—

Peaceful moonbeams light thy chamber,

In thy cradle creep;

I will tell to thee a story,

Pure as dewdrop glow,

Close those two beloved eyelids—

Lullaby, By-low!

List! The Terek o’er its pebbles

Blusters through the vale,

On its shores the evil Chechen

Whets his murdrous blade;

Yet thy father grey in battle—

Guards thee, child of woe,

Safely rest thee in thy cradle,

Lullaby, By-low!

Grievous times will sure befall thee,

Danger, slaughterous fire—

Thou shalt on a charger gallop,

Curbing at desire;

And a saddle girth all silken

Sadly I will sew,

Slumber now my wide-eyed darling,

Lullaby, By-low!

When I see thee, my own Being,

As a Cossack true,

Must I only convoy give thee—

“Mother dear, adieu!”

Nightly in the empty chamber

Blinding tears will flow,

Sleep my angel, sweetest dear one,

Lullaby, By-low!

Thy return I’ll wait lamenting

As the days go by,

Ardent for thee praying,—fearing

In the cards to spy.

I shall fancy thou wilt suffer,

As a stranger grow—

Sleep while yet thou nought regrettest,

Lullaby, By-low!

I will send a holy image

’Gainst the foe with thee,

To it kneeling, dearest Being,

Pray with piety!

Think of me in bloody battle,

Dearest child of woe,

Slumber soft within thy cradle,

Lullaby, By-low!

(the translation is not mine, merely edited according to the original. Thanks for reading)

Михаил Лермонтов КАЗАЧЬЯ КОЛЫБЕЛЬНАЯ ПЕСНЯ

Спи, младенец мой прекрасный,

Баюшки-баю.

Тихо смотрит месяц ясный

В колыбель твою.

Стану сказывать я сказки,

Песенку спою;

Ты ж дремли, закрывши глазки,

Баюшки-баю.

По камням струится Терек,

Плещет мутный вал;

Злой чечен ползет на берег,

Точит свой кинжал;

Но отец твой старый воин,

Закален в бою:

Спи, малютка, будь спокоен,

Баюшки-баю.

Сам узнаешь, будет время,

Бранное житье;

Смело вденешь ногу в стремя

И возьмешь ружье.

Я седельце боевое

Шелком разошью...

Спи, дитя мое родное,

Баюшки-баю.

Богатырь ты будешь с виду

И казак душой.

Провожать тебя я выйду -

Ты махнешь рукой...

Сколько горьких слез украдкой

Я в ту ночь пролью!..

Спи, мой ангел, тихо, сладко,

Баюшки-баю.

Стану я тоской томиться,

Безутешно ждать;

Стану целый день молиться,

По ночам гадать;

Стану думать, что скучаешь

Ты в чужом краю...

Спи ж, пока забот не знаешь,

Баюшки-баю.

Дам тебе я на дорогу

Образок святой:

Ты его, моляся богу,

Ставь перед собой;

Да, готовясь в бой опасный,

Помни мать свою...

Спи, младенец мой прекрасный,

Баюшки-баю.

Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841). Cradle Song Of The Cossack Mother

Slumber sweet, my fairest baby,

Slumber calmly, sleep—

Peaceful moonbeams light thy chamber,

In thy cradle creep;

I will tell to thee a story,

Pure as dewdrop glow,

Close those two beloved eyelids—

Lullaby, By-low!

List! The Terek o’er its pebbles

Blusters through the vale,

On its shores the evil Chechen

Whets his murdrous blade;

Yet thy father grey in battle—

Guards thee, child of woe,

Safely rest thee in thy cradle,

Lullaby, By-low!

Grievous times will sure befall thee,

Danger, slaughterous fire—

Thou shalt on a charger gallop,

Curbing at desire;

And a saddle girth all silken

Sadly I will sew,

Slumber now my wide-eyed darling,

Lullaby, By-low!

When I see thee, my own Being,

As a Cossack true,

Must I only convoy give thee—

“Mother dear, adieu!”

Nightly in the empty chamber

Blinding tears will flow,

Sleep my angel, sweetest dear one,

Lullaby, By-low!

Thy return I’ll wait lamenting

As the days go by,

Ardent for thee praying,—fearing

In the cards to spy.

I shall fancy thou wilt suffer,

As a stranger grow—

Sleep while yet thou nought regrettest,

Lullaby, By-low!

I will send a holy image

’Gainst the foe with thee,

To it kneeling, dearest Being,

Pray with piety!

Think of me in bloody battle,

Dearest child of woe,

Slumber soft within thy cradle,

Lullaby, By-low!

(the translation is not mine, merely edited according to the original. Thanks for reading)

Михаил Лермонтов КАЗАЧЬЯ КОЛЫБЕЛЬНАЯ ПЕСНЯ

Спи, младенец мой прекрасный,

Баюшки-баю.

Тихо смотрит месяц ясный

В колыбель твою.

Стану сказывать я сказки,

Песенку спою;

Ты ж дремли, закрывши глазки,

Баюшки-баю.

По камням струится Терек,

Плещет мутный вал;

Злой чечен ползет на берег,

Точит свой кинжал;

Но отец твой старый воин,

Закален в бою:

Спи, малютка, будь спокоен,

Баюшки-баю.

Сам узнаешь, будет время,

Бранное житье;

Смело вденешь ногу в стремя

И возьмешь ружье.

Я седельце боевое

Шелком разошью...

Спи, дитя мое родное,

Баюшки-баю.

Богатырь ты будешь с виду

И казак душой.

Провожать тебя я выйду -

Ты махнешь рукой...

Сколько горьких слез украдкой

Я в ту ночь пролью!..

Спи, мой ангел, тихо, сладко,

Баюшки-баю.

Стану я тоской томиться,

Безутешно ждать;

Стану целый день молиться,

По ночам гадать;

Стану думать, что скучаешь

Ты в чужом краю...

Спи ж, пока забот не знаешь,

Баюшки-баю.

Дам тебе я на дорогу

Образок святой:

Ты его, моляся богу,

Ставь перед собой;

Да, готовясь в бой опасный,

Помни мать свою...

Спи, младенец мой прекрасный,

Баюшки-баю.

Published on May 29, 2013 08:08