Lara Biyuts's Blog, page 7

October 7, 2011

story

SREDNI VASHTAR

by

SAKI

"And while they debated the matter among themselves, Conradin made himself another piece of toast."

(Saki)

Conradin was ten years old, and the doctor had pronounced his professional opinion that the boy would not live another five years. The doctor was silky and effete, and counted for little, but his opinion was endorsed by Mrs. De Ropp, who counted for nearly everything. Mrs. De Ropp was Conradin's cousin and guardian, and in his eyes she represented those three-fifths of the world that are necessary and disagreeable and real; the other two-fifths, in perpetual antagonism to the foregoing, were summed up in himself and his imagination. One of these days Conradin supposed he would succumb to the mastering pressure of wearisome necessary things---such as illnesses and coddling restrictions and drawn-out dulness. Without his imagination, which was rampant under the spur of loneliness, he would have succumbed long ago. Mrs. De Ropp would never, in her honestest moments, have confessed to herself that she disliked Conradin, though she might have been dimly aware that thwarting him "for his good" was a duty which she did not find particularly irksome. Conradin hated her with a desperate sincerity which he was perfectly able to mask. Such few pleasures as he could contrive for himself gained an added relish from the likelihood that they would be displeasing to his guardian, and from the realm of his imagination she was locked out---an unclean thing, which should find no entrance.

In the dull, cheerless garden, overlooked by so many windows that were ready to open with a message not to do this or that, or a reminder that medicines were due, he found little attraction. The few fruit-trees that it contained were set jealously apart from his plucking, as though they were rare specimens of their kind blooming in an arid waste; it would probably have been difficult to find a market-gardener who would have offered ten shillings for their entire yearly produce. In a forgotten corner, however, almost hidden behind a dismal shrubbery, was a disused tool-shed of respectable proportions, and within its walls Conradin found a haven, something that took on the varying aspects of a playroom and a cathedral. He had peopled it with a legion of familiar phantoms, evoked partly from fragments of history and partly from his own brain, but it also boasted two inmates of flesh and blood. In one corner lived a ragged-plumaged Houdan hen, on which the boy lavished an affection that had scarcely another outlet. Further back in the gloom stood a large hutch, divided into two compartments, one of which was fronted with close iron bars. This was the abode of a large polecat-ferret, which a friendly butcher-boy had once smuggled, cage and all, into its present quarters, in exchange for a long-secreted hoard of small silver. Conradin was dreadfully afraid of the lithe, sharp-fanged beast, but it was his most treasured possession. Its very presence in the tool-shed was a secret and fearful joy, to be kept scrupulously from the knowledge of the Woman, as he privately dubbed his cousin. And one day, out of Heaven knows what material, he spun the beast a wonderful name, and from that moment it grew into a god and a religion. The Woman indulged in religion once a week at a church near by, and took Conradin with her, but to him the church service was an alien rite in the House of Rimmon. Every Thursday, in the dim and musty silence of the tool-shed, he worshipped with mystic and elaborate ceremonial before the wooden hutch where dwelt Sredni Vashtar, the great ferret. Red flowers in their season and scarlet berries in the winter-time were offered at his shrine, for he was a god who laid some special stress on the fierce impatient side of things, as opposed to the Woman's religion, which, as far as Conradin could observe, went to great lengths in the contrary direction. And on great festivals powdered nutmeg was strewn in front of his hutch, an important feature of the offering being that the nutmeg had to be stolen. These festivals were of irregular occurrence, and were chiefly appointed to celebrate some passing event. On one occasion, when Mrs. De Ropp suffered from acute toothache for three days, Conradin kept up the festival during the entire three days, and almost succeeded in persuading himself that Sredni Vashtar was personally responsible for the toothache. If the malady had lasted for another day the supply of nutmeg would have given out.

The Houdan hen was never drawn into the cult of Sredni Vashtar. Conradin had long ago settled that she was an Anabaptist. He did not pretend to have the remotest knowledge as to what an Anabaptist was, but he privately hoped that it was dashing and not very respectable. Mrs. De Ropp was the ground plan on which he based and detested all respectability.

After a while Conradin's absorption in the tool-shed began to attract the notice of his guardian. "It is not good for him to be pottering down there in all weathers," she promptly decided, and at breakfast one morning she announced that the Houdan hen had been sold and taken away overnight. With her shortsighted eyes she peered at Conradin, waiting for an outbreak of rage and sorrow, which she was ready to rebuke with a flow of excellent precepts and reasoning. But Conradin said nothing: there was nothing to be said. Something perhaps in his white set face gave her a momentary qualm, for at tea that afternoon there was toast on the table, a delicacy which she usually banned on the ground that it was bad for him; also because the making of it "gave trouble," a deadly offence in the middle-class feminine eye.

"I thought you liked toast," she exclaimed, with an injured air, observing that he did not touch it.

"Sometimes," said Conradin.

In the shed that evening there was an innovation in the worship of the hutch-god. Conradin had been wont to chant his praises, tonight be asked a boon.

"Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar."

The thing was not specified. As Sredni Vashtar was a god he must be supposed to know. And choking back a sob as he looked at that other empty comer, Conradin went back to the world he so hated.

And every night, in the welcome darkness of his bedroom, and every evening in the dusk of the tool-shed, Conradin's bitter litany went up: "Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar."

Mrs. De Ropp noticed that the visits to the shed did not cease, and one day she made a further journey of inspection.

"What are you keeping in that locked hutch?" she asked.

"I believe it's guinea-pigs. I'll have them all cleared away."

Conradin shut his lips tight, but the Woman ransacked his bedroom till she found the carefully hidden key, and forthwith marched down to the shed to complete her discovery. It was a cold afternoon, and Conradin had been bidden to keep to the house. From the furthest window of the dining-room the door of the shed could just be seen beyond the corner of the shrubbery, and there Conradin stationed himself. He saw the Woman enter, and then be imagined her opening the door of the sacred hutch and peering down with her short-sighted eyes into the thick straw bed where his god lay hidden. Perhaps she would prod at the straw in her clumsy impatience. And Conradin fervently breathed his prayer for the last time. But he knew as he prayed that he did not believe. He knew that the Woman would come out presently with that pursed smile he loathed so well on her face, and that in an hour or two the gardener would carry away his wonderful god, a god no longer, but a simple brown ferret in a hutch. And he knew that the Woman would triumph always as she triumphed now, and that he would grow ever more sickly under her pestering and domineering and superior wisdom, till one day nothing would matter much more with him, and the doctor would be proved right. And in the sting and misery of his defeat, he began to chant loudly and defiantly the hymn of his threatened idol:

Sredni Vashtar went forth,

His thoughts were red thoughts and his teeth were white.

His enemies called for peace, but he brought them death.

Sredni Vashtar the Beautiful.

And then of a sudden he stopped his chanting and drew closer to the windowpane. The door of the shed still stood ajar as it had been left, and the minutes were slipping by. They were long minutes, but they slipped by nevertheless. He watched the starlings running and flying in little parties across the lawn; he counted them over and over again, with one eye always on that swinging door. A sour-faced maid came in to lay the table for tea, and still Conradin stood and waited and watched. Hope had crept by inches into his heart, and now a look of triumph began to blaze in his eyes that had only known the wistful patience of defeat. Under his breath, with a furtive exultation, he began once again the paean of victory and devastation. And presently his eyes were rewarded: out through that doorway came a long, low, yellow-and-brown beast, with eyes a-blink at the waning daylight, and dark wet stains around the fur of jaws and throat. Conradin dropped on his knees. The great polecat-ferret made its way down to a small brook at the foot of the garden, drank for a moment, then crossed a little plank bridge and was lost to sight in the bushes. Such was the passing of Sredni Vashtar.

"Tea is ready," said the sour-faced maid; "where is the mistress?"

"She went down to the shed some time ago," said Conradin. And while the maid went to summon her mistress to tea, Conradin fished a toasting-fork out of the sideboard drawer and proceeded to toast himself a piece of bread. And during the toasting of it and the buttering of it with much butter and the slow enjoyment of eating it, Conradin listened to the noises and silences which fell in quick spasms beyond the dining-room door. The loud foolish screaming of the maid, the answering chorus of wondering ejaculations from the kitchen region, the scuttering footsteps and hurried embassies for outside help, and then, after a lull, the scared sobbings and the shuffling tread of those who bore a heavy burden into the house.

"Whoever will break it to the poor child? I couldn't for the life of me!" exclaimed a shrill voice. And while they debated the matter among themselves, Conradin made himself another piece of toast.

The End

by

SAKI

"And while they debated the matter among themselves, Conradin made himself another piece of toast."

(Saki)

Conradin was ten years old, and the doctor had pronounced his professional opinion that the boy would not live another five years. The doctor was silky and effete, and counted for little, but his opinion was endorsed by Mrs. De Ropp, who counted for nearly everything. Mrs. De Ropp was Conradin's cousin and guardian, and in his eyes she represented those three-fifths of the world that are necessary and disagreeable and real; the other two-fifths, in perpetual antagonism to the foregoing, were summed up in himself and his imagination. One of these days Conradin supposed he would succumb to the mastering pressure of wearisome necessary things---such as illnesses and coddling restrictions and drawn-out dulness. Without his imagination, which was rampant under the spur of loneliness, he would have succumbed long ago. Mrs. De Ropp would never, in her honestest moments, have confessed to herself that she disliked Conradin, though she might have been dimly aware that thwarting him "for his good" was a duty which she did not find particularly irksome. Conradin hated her with a desperate sincerity which he was perfectly able to mask. Such few pleasures as he could contrive for himself gained an added relish from the likelihood that they would be displeasing to his guardian, and from the realm of his imagination she was locked out---an unclean thing, which should find no entrance.

In the dull, cheerless garden, overlooked by so many windows that were ready to open with a message not to do this or that, or a reminder that medicines were due, he found little attraction. The few fruit-trees that it contained were set jealously apart from his plucking, as though they were rare specimens of their kind blooming in an arid waste; it would probably have been difficult to find a market-gardener who would have offered ten shillings for their entire yearly produce. In a forgotten corner, however, almost hidden behind a dismal shrubbery, was a disused tool-shed of respectable proportions, and within its walls Conradin found a haven, something that took on the varying aspects of a playroom and a cathedral. He had peopled it with a legion of familiar phantoms, evoked partly from fragments of history and partly from his own brain, but it also boasted two inmates of flesh and blood. In one corner lived a ragged-plumaged Houdan hen, on which the boy lavished an affection that had scarcely another outlet. Further back in the gloom stood a large hutch, divided into two compartments, one of which was fronted with close iron bars. This was the abode of a large polecat-ferret, which a friendly butcher-boy had once smuggled, cage and all, into its present quarters, in exchange for a long-secreted hoard of small silver. Conradin was dreadfully afraid of the lithe, sharp-fanged beast, but it was his most treasured possession. Its very presence in the tool-shed was a secret and fearful joy, to be kept scrupulously from the knowledge of the Woman, as he privately dubbed his cousin. And one day, out of Heaven knows what material, he spun the beast a wonderful name, and from that moment it grew into a god and a religion. The Woman indulged in religion once a week at a church near by, and took Conradin with her, but to him the church service was an alien rite in the House of Rimmon. Every Thursday, in the dim and musty silence of the tool-shed, he worshipped with mystic and elaborate ceremonial before the wooden hutch where dwelt Sredni Vashtar, the great ferret. Red flowers in their season and scarlet berries in the winter-time were offered at his shrine, for he was a god who laid some special stress on the fierce impatient side of things, as opposed to the Woman's religion, which, as far as Conradin could observe, went to great lengths in the contrary direction. And on great festivals powdered nutmeg was strewn in front of his hutch, an important feature of the offering being that the nutmeg had to be stolen. These festivals were of irregular occurrence, and were chiefly appointed to celebrate some passing event. On one occasion, when Mrs. De Ropp suffered from acute toothache for three days, Conradin kept up the festival during the entire three days, and almost succeeded in persuading himself that Sredni Vashtar was personally responsible for the toothache. If the malady had lasted for another day the supply of nutmeg would have given out.

The Houdan hen was never drawn into the cult of Sredni Vashtar. Conradin had long ago settled that she was an Anabaptist. He did not pretend to have the remotest knowledge as to what an Anabaptist was, but he privately hoped that it was dashing and not very respectable. Mrs. De Ropp was the ground plan on which he based and detested all respectability.

After a while Conradin's absorption in the tool-shed began to attract the notice of his guardian. "It is not good for him to be pottering down there in all weathers," she promptly decided, and at breakfast one morning she announced that the Houdan hen had been sold and taken away overnight. With her shortsighted eyes she peered at Conradin, waiting for an outbreak of rage and sorrow, which she was ready to rebuke with a flow of excellent precepts and reasoning. But Conradin said nothing: there was nothing to be said. Something perhaps in his white set face gave her a momentary qualm, for at tea that afternoon there was toast on the table, a delicacy which she usually banned on the ground that it was bad for him; also because the making of it "gave trouble," a deadly offence in the middle-class feminine eye.

"I thought you liked toast," she exclaimed, with an injured air, observing that he did not touch it.

"Sometimes," said Conradin.

In the shed that evening there was an innovation in the worship of the hutch-god. Conradin had been wont to chant his praises, tonight be asked a boon.

"Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar."

The thing was not specified. As Sredni Vashtar was a god he must be supposed to know. And choking back a sob as he looked at that other empty comer, Conradin went back to the world he so hated.

And every night, in the welcome darkness of his bedroom, and every evening in the dusk of the tool-shed, Conradin's bitter litany went up: "Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar."

Mrs. De Ropp noticed that the visits to the shed did not cease, and one day she made a further journey of inspection.

"What are you keeping in that locked hutch?" she asked.

"I believe it's guinea-pigs. I'll have them all cleared away."

Conradin shut his lips tight, but the Woman ransacked his bedroom till she found the carefully hidden key, and forthwith marched down to the shed to complete her discovery. It was a cold afternoon, and Conradin had been bidden to keep to the house. From the furthest window of the dining-room the door of the shed could just be seen beyond the corner of the shrubbery, and there Conradin stationed himself. He saw the Woman enter, and then be imagined her opening the door of the sacred hutch and peering down with her short-sighted eyes into the thick straw bed where his god lay hidden. Perhaps she would prod at the straw in her clumsy impatience. And Conradin fervently breathed his prayer for the last time. But he knew as he prayed that he did not believe. He knew that the Woman would come out presently with that pursed smile he loathed so well on her face, and that in an hour or two the gardener would carry away his wonderful god, a god no longer, but a simple brown ferret in a hutch. And he knew that the Woman would triumph always as she triumphed now, and that he would grow ever more sickly under her pestering and domineering and superior wisdom, till one day nothing would matter much more with him, and the doctor would be proved right. And in the sting and misery of his defeat, he began to chant loudly and defiantly the hymn of his threatened idol:

Sredni Vashtar went forth,

His thoughts were red thoughts and his teeth were white.

His enemies called for peace, but he brought them death.

Sredni Vashtar the Beautiful.

And then of a sudden he stopped his chanting and drew closer to the windowpane. The door of the shed still stood ajar as it had been left, and the minutes were slipping by. They were long minutes, but they slipped by nevertheless. He watched the starlings running and flying in little parties across the lawn; he counted them over and over again, with one eye always on that swinging door. A sour-faced maid came in to lay the table for tea, and still Conradin stood and waited and watched. Hope had crept by inches into his heart, and now a look of triumph began to blaze in his eyes that had only known the wistful patience of defeat. Under his breath, with a furtive exultation, he began once again the paean of victory and devastation. And presently his eyes were rewarded: out through that doorway came a long, low, yellow-and-brown beast, with eyes a-blink at the waning daylight, and dark wet stains around the fur of jaws and throat. Conradin dropped on his knees. The great polecat-ferret made its way down to a small brook at the foot of the garden, drank for a moment, then crossed a little plank bridge and was lost to sight in the bushes. Such was the passing of Sredni Vashtar.

"Tea is ready," said the sour-faced maid; "where is the mistress?"

"She went down to the shed some time ago," said Conradin. And while the maid went to summon her mistress to tea, Conradin fished a toasting-fork out of the sideboard drawer and proceeded to toast himself a piece of bread. And during the toasting of it and the buttering of it with much butter and the slow enjoyment of eating it, Conradin listened to the noises and silences which fell in quick spasms beyond the dining-room door. The loud foolish screaming of the maid, the answering chorus of wondering ejaculations from the kitchen region, the scuttering footsteps and hurried embassies for outside help, and then, after a lull, the scared sobbings and the shuffling tread of those who bore a heavy burden into the house.

"Whoever will break it to the poor child? I couldn't for the life of me!" exclaimed a shrill voice. And while they debated the matter among themselves, Conradin made himself another piece of toast.

The End

Published on October 07, 2011 03:00

October 6, 2011

THE NEEDS OF THE NAVY

Introduction

"And such was his passion for Hierocles

that he kissed him in a place

which it is indecent even to mention…"

(THE LIFE OF ANTONINUS HELIOGABALUS)

"But after all we are not children,

not illiterate juvenile delinquents, not English public school boys

who after a night of homosexual romps

have to endure the paradox of reading the Ancients

in expurgated versions."

(V. Nabokov, On a Book Entitled Lolita)

This little tale was originally published in the "Juvenilia" section of Snowdrops from a Curate's Garden, Crowley's obscene miscellany, one hundred copies of which he had printed privately (most likely in Paris) in 1904, although they bear the ficticious appellation "1881 A.D., Cosmopoli."

as you know, the edition was destroyed by Britain censorship in 1926. Now you can take the opportunity to read the story.

THE NEEDS OF THE NAVY

by ALEISTER CROWLEY

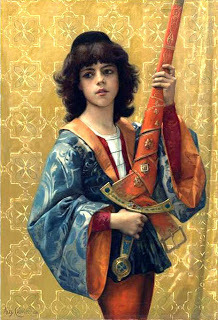

The air of the room was quite sweet and heavy with the savour of forbidden kisses; a faint moist sense of sweat steamed up in the twilight, and there was a sound of breath that did not dare to breathe, of sighs choked by fear. The midshipman's head silently turned round and his tongue pushed languidly forward to touch the lips of the lieutenant. A sound in the next room; both trembled violently, sprang from the sofa where they had been lying and hastily arranged the disorder their passion had made necessary. The middy took his lover's hand, raised it to his lips, bit it hard with sudden mad desire and whispered, in a voice shuddering with unsatiated lust "Ah God! Ah God! I love you now!" He slipped through the door and left Andrew Clayton to sweet memories and disquieting thought of the future. For Monty Le W-- had never given him his love before. Monty was a dark, languid-eyed boy with jetty hair; there was about him the indefinable air that sexual perverts recognize so quickly, a closer union than masonry can boast. In fact, he had not been on board H.M.S. Osiris a week before the Captain had promoted him to a dignity sufficiently high to excite the envy of the boys who had till then held the proud distinction of favourite catamite. A furious battle between the jealous beauties ended in their growing so excited over the spilt blood and the violent physical pain that the spectators were scandalized by the sight of an impromptu orgie as infuriate as the fight had originally been. The boys were still fast friends, but Monty was first favourite with the Captain and tyrannized over him to the previously-unheard-of extent of demanding reciprocity en affaire d'amour. The Captain on his part only asked fidelity; and indeed Monty had grown to love him so dearly that the thought of an adultery would have been insupportable. One day, however, a sudden desire came upon him towards the most popular of the lieutenants, Andrew Clayton, a man of violent passions not usually associated with fair hair and rather timid grey eyes. Andrew saw the sly looks of the midshipman and one day went into his cabin and, stepping to his side without a word, gave him a fierce kiss, while his hand sought to awake desire in an even more direct manner. But the passing fancy of the boy had gone, and he rudely repulsed the advances of his would-be lover. Andrew, with great self-command, withdrew in silence. Next day, however, they were both called before the Captain, read a long lecture on the sin of paederasty and severely reprimanded. It was evident that Captain Spelton liked his forehead very well as it was, and meant to keep a sharp look-out. Monty in his innocence was terribly indignant and naturally became quite ready to cuckold the Captain if he could. At mess that evening he managed to whisper "you shall have me if you still -" the immediate result of which was considerably embarrassing to Andrew. But all the endeavours they made to meet and steal a kiss occasionally were always frustrated as if by accident, though they now knew it must be of set purpose. Andrew suggested at last that, to allay suspicion, he should choose another middy and pretend to make violent love to him. Monty's jealousy said no, and only after a long time was he persuaded to agree. "Katie" Ambrose, the boy selected for this vicarious duty, was a dirty little fellow of the most vicious type. His favourite fancy, in public, was to lie on his back and to endeavour to catch in his mouth, and swallow, his own emissions, and he was also constantly degrading his rank by licking the genitals, or the feet, of the dirtiest sailors and stokers on the ship. He was only glad from the social status it gave him when Andrew made overtures of love. Monty would have himself preferred this choice, arguing that Andrew would have himself preferred this choice, arguing that Andrew could never be really enamoured of so vicious a boy, but what he saw three weeks after undeceived him. On this wise.

One night the Captain, being restless, suggested a tour of inspection, and the two lovers stole quietly out of their cabin. They came after a time to where Andrew and Ambrose were, and were lucky enough to catch the former in the very act of sacrificing at the most holy altar, while the boy, turned half round, was gently chewing and licking the armpit of the perspiring lieutenant. One finger of his free hand sought to penetrate the other's shrine, while the hand underneath him titillated his own genitals in unison with the motions of his lover. The act was consummated; gasping, heaving, breathless, they sink lower on the bed. Their tongues mingle lazily; the elder man withdraws slowly; a pleasant sound announces his exit. Hardly a moment and the boy gives his lover a signal. The latter turns over while Ambrose rises and sits over him while the sweet salt offering, spiced now by the god to whom it is offered, trickles daintily into the open mouth of the languorous man. Then the boy slips down into his lover's arms: they share the incense with mingled mouths until the flavour is appeased and they swallow it with the first blush of reawakening desire. "Katie" eagerly reverses his position to prepare for a new embrace; but Monty whispers to the Captain: "Darling, I can bear it no longer; come back!" They never slept at all that night; but I never heard either of them regret the fact. But Monty was terribly disgusted with Andrew, and when little Ambrose struck Monty (who had called him, with naive eloquence, "Suck-shit") the latter knocked him down and kicked him. The lieutenant, who was near, had to interfere, and the dark languorous boy was punished. This mean revenge (as he understood it) irritated Monty still more and he eventually refused to speak to Andrew at all.

It was the night of a big dinner ashore and Monty Le W-- had gone up to a little sitting-room which was next [to the] billiard-room, to wait for the Captain. Unperceived Andrew had followed him and was now lurking behind the heavy curtain that hung over the door; he listened to the boys' muttered soliloquy, disturbed only by the noisier laughter and curses of the billiard- room. Spelton was long - damned long - coming; no doubt of that. And Monty's desires were getting less controllable every minute. At last he took down his trousers and began to play with himself, hoping to ease a little his discomfort. At this moment Andrew glided forward and whispered "If you speak we are both lost. Your dress . . ." The frightened boy made a movement of agony. He was terribly angry, and yet dared not speak or make the least sound. After the other affair he knew the Captain would never believe his story. The lusty lieutenant took out a weapon fiery and enormous, and began to seek admission. The boy, with all the force of the sphincter, resisted. A sharp tap or two on the coccyx, however, reminded him that he had a bold lover, who would stick at nothing, and he gave way. The whole length of his lover's yard was engulfed in one great push, and, accustomed as he was to the Captain's penis, he could hardly repress a cry of pain. The ravisher was far longer and thicker and cared a great deal less about any pain he might inflict. And he plunged like a mad horse! At last the welcome climax, and a perfect deluge of kisses bitten hard into his olive neck. And then the luxurious confession with which this story began.

Left to himself, Clayton invented incidentally twenty-three quite new curses, called Le W-- a little bitch, kissed the mark of the little bitch's teeth on his hand, and generally conducted himself as an officer and a gentleman would do, provided he were also a devout Christian. He foresaw trouble. It came pretty quickly. Two days afterwards Clayton had to quit his lover's room in a great hurry, as heavy footsteps trod the passage. The Captain was in his dressing-gown and proved quite Arcadian beneath. He was in bed in a jiffy, and discovered heat and moisture to an extent unwarranted by the climate. "I thought you would never come, love," sighed the charming middy, with resourceful tact, "so I've been whiling away the time." "I'm here now," said his lover, and applied his lips to the dark altar of his desire. That was very moist too, and the Captain's inquisitive tongue soon penetrated its secrecies and became aware of a strong warm taste as of incense recently offered. "I envy you your amusement," he observed, with delicate irony, "you appear to have succeeded at last in following my advice to go and bugger yourself!" He said no more just then, but came round with a sharp knife two days later to both the lovers and said he thought their accomplishments, if unique, were unnatural. But the knife cut both knots at once; he told Lord Cartington at their tête-à-tête dinner the next day that there seemed to be no end to the variety of entrees which had as a basis - oysters.

"Katie" Ambrose grew in wisdom and stature and in favour with god and man.

The End

Tweet

Published on October 06, 2011 05:15

Introduction"And such was his passion for Hierocles that ...

Introduction

"And such was his passion for Hierocles

that he kissed him in a place

which it is indecent even to mention…"

(THE LIFE OF ANTONINUS HELIOGABALUS)

"But after all we are not children,

not illiterate juvenile delinquents, not English public school boys

who after a night of homosexual romps

have to endure the paradox of reading the Ancients

in expurgated versions."

(V. Nabokov, On a Book Entitled Lolita)

This little tale was originally published in the "Juvenilia" section of Snowdrops from a Curate's Garden, Crowley's obscene miscellany, one hundred copies of which he had printed privately (most likely in Paris) in 1904, although they bear the ficticious appellation "1881 A.D., Cosmopoli."

as you know, the edition was destroyed by Britain censorship in 1926. Now you can take the opportunity to read the story.

THE NEEDS OF THE NAVY

by ALEISTER CROWLEY

The air of the room was quite sweet and heavy with the savour of forbidden kisses; a faint moist sense of sweat steamed up in the twilight, and there was a sound of breath that did not dare to breathe, of sighs choked by fear. The midshipman's head silently turned round and his tongue pushed languidly forward to touch the lips of the lieutenant. A sound in the next room; both trembled violently, sprang from the sofa where they had been lying and hastily arranged the disorder their passion had made necessary. The middy took his lover's hand, raised it to his lips, bit it hard with sudden mad desire and whispered, in a voice shuddering with unsatiated lust "Ah God! Ah God! I love you now!" He slipped through the door and left Andrew Clayton to sweet memories and disquieting thought of the future. For Monty Le W-- had never given him his love before. Monty was a dark, languid-eyed boy with jetty hair; there was about him the indefinable air that sexual perverts recognize so quickly, a closer union than masonry can boast. In fact, he had not been on board H.M.S. Osiris a week before the Captain had promoted him to a dignity sufficiently high to excite the envy of the boys who had till then held the proud distinction of favourite catamite. A furious battle between the jealous beauties ended in their growing so excited over the spilt blood and the violent physical pain that the spectators were scandalized by the sight of an impromptu orgie as infuriate as the fight had originally been. The boys were still fast friends, but Monty was first favourite with the Captain and tyrannized over him to the previously-unheard-of extent of demanding reciprocity en affaire d'amour. The Captain on his part only asked fidelity; and indeed Monty had grown to love him so dearly that the thought of an adultery would have been insupportable. One day, however, a sudden desire came upon him towards the most popular of the lieutenants, Andrew Clayton, a man of violent passions not usually associated with fair hair and rather timid grey eyes. Andrew saw the sly looks of the midshipman and one day went into his cabin and, stepping to his side without a word, gave him a fierce kiss, while his hand sought to awake desire in an even more direct manner. But the passing fancy of the boy had gone, and he rudely repulsed the advances of his would-be lover. Andrew, with great self-command, withdrew in silence. Next day, however, they were both called before the Captain, read a long lecture on the sin of paederasty and severely reprimanded. It was evident that Captain Spelton liked his forehead very well as it was, and meant to keep a sharp look-out. Monty in his innocence was terribly indignant and naturally became quite ready to cuckold the Captain if he could. At mess that evening he managed to whisper "you shall have me if you still -" the immediate result of which was considerably embarrassing to Andrew. But all the endeavours they made to meet and steal a kiss occasionally were always frustrated as if by accident, though they now knew it must be of set purpose. Andrew suggested at last that, to allay suspicion, he should choose another middy and pretend to make violent love to him. Monty's jealousy said no, and only after a long time was he persuaded to agree. "Katie" Ambrose, the boy selected for this vicarious duty, was a dirty little fellow of the most vicious type. His favourite fancy, in public, was to lie on his back and to endeavour to catch in his mouth, and swallow, his own emissions, and he was also constantly degrading his rank by licking the genitals, or the feet, of the dirtiest sailors and stokers on the ship. He was only glad from the social status it gave him when Andrew made overtures of love. Monty would have himself preferred this choice, arguing that Andrew would have himself preferred this choice, arguing that Andrew could never be really enamoured of so vicious a boy, but what he saw three weeks after undeceived him. On this wise.

One night the Captain, being restless, suggested a tour of inspection, and the two lovers stole quietly out of their cabin. They came after a time to where Andrew and Ambrose were, and were lucky enough to catch the former in the very act of sacrificing at the most holy altar, while the boy, turned half round, was gently chewing and licking the armpit of the perspiring lieutenant. One finger of his free hand sought to penetrate the other's shrine, while the hand underneath him titillated his own genitals in unison with the motions of his lover. The act was consummated; gasping, heaving, breathless, they sink lower on the bed. Their tongues mingle lazily; the elder man withdraws slowly; a pleasant sound announces his exit. Hardly a moment and the boy gives his lover a signal. The latter turns over while Ambrose rises and sits over him while the sweet salt offering, spiced now by the god to whom it is offered, trickles daintily into the open mouth of the languorous man. Then the boy slips down into his lover's arms: they share the incense with mingled mouths until the flavour is appeased and they swallow it with the first blush of reawakening desire. "Katie" eagerly reverses his position to prepare for a new embrace; but Monty whispers to the Captain: "Darling, I can bear it no longer; come back!" They never slept at all that night; but I never heard either of them regret the fact. But Monty was terribly disgusted with Andrew, and when little Ambrose struck Monty (who had called him, with naive eloquence, "Suck-shit") the latter knocked him down and kicked him. The lieutenant, who was near, had to interfere, and the dark languorous boy was punished. This mean revenge (as he understood it) irritated Monty still more and he eventually refused to speak to Andrew at all.

It was the night of a big dinner ashore and Monty Le W-- had gone up to a little sitting-room which was next [to the] billiard-room, to wait for the Captain. Unperceived Andrew had followed him and was now lurking behind the heavy curtain that hung over the door; he listened to the boys' muttered soliloquy, disturbed only by the noisier laughter and curses of the billiard- room. Spelton was long - damned long - coming; no doubt of that. And Monty's desires were getting less controllable every minute. At last he took down his trousers and began to play with himself, hoping to ease a little his discomfort. At this moment Andrew glided forward and whispered "If you speak we are both lost. Your dress . . ." The frightened boy made a movement of agony. He was terribly angry, and yet dared not speak or make the least sound. After the other affair he knew the Captain would never believe his story. The lusty lieutenant took out a weapon fiery and enormous, and began to seek admission. The boy, with all the force of the sphincter, resisted. A sharp tap or two on the coccyx, however, reminded him that he had a bold lover, who would stick at nothing, and he gave way. The whole length of his lover's yard was engulfed in one great push, and, accustomed as he was to the Captain's penis, he could hardly repress a cry of pain. The ravisher was far longer and thicker and cared a great deal less about any pain he might inflict. And he plunged like a mad horse! At last the welcome climax, and a perfect deluge of kisses bitten hard into his olive neck. And then the luxurious confession with which this story began.

Left to himself, Clayton invented incidentally twenty-three quite new curses, called Le W-- a little bitch, kissed the mark of the little bitch's teeth on his hand, and generally conducted himself as an officer and a gentleman would do, provided he were also a devout Christian. He foresaw trouble. It came pretty quickly. Two days afterwards Clayton had to quit his lover's room in a great hurry, as heavy footsteps trod the passage. The Captain was in his dressing-gown and proved quite Arcadian beneath. He was in bed in a jiffy, and discovered heat and moisture to an extent unwarranted by the climate. "I thought you would never come, love," sighed the charming middy, with resourceful tact, "so I've been whiling away the time." "I'm here now," said his lover, and applied his lips to the dark altar of his desire. That was very moist too, and the Captain's inquisitive tongue soon penetrated its secrecies and became aware of a strong warm taste as of incense recently offered. "I envy you your amusement," he observed, with delicate irony, "you appear to have succeeded at last in following my advice to go and bugger yourself!" He said no more just then, but came round with a sharp knife two days later to both the lovers and said he thought their accomplishments, if unique, were unnatural. But the knife cut both knots at once; he told Lord Cartington at their tête-à-tête dinner the next day that there seemed to be no end to the variety of entrees which had as a basis - oysters.

"Katie" Ambrose grew in wisdom and stature and in favour with god and man.

The End

Published on October 06, 2011 05:15

September 7, 2011

The Autumn Gay Tints

"…Ofyouth, and home, and those sweet time,Whenlast I heard their soothing chime.Thosejoyous hours are passed away;And manya heart, that then was gay…" (from the old song)

*A Petal of the Mist*

A petal of the mist fell on mytweed,a fragrant shade of flowers of thehope.My garden used to have the flowers'scent. A kind of dope. Defoliated now. I used to pluck the flowers for thethrilling and magic fortunes-telling. Iconjured for tenderness--devoting, holdingbreath, awaiting for a miracle. In awe. Sohopelessly. Now, borders of the seasons allcrumbled and quickly disappeared in thehelix between the petal of the mist andscarp of hope.Lara Biyuts © 2008

*caught in the toils of autumn*

Hours,days, weeks rustle after;theamber blizzard rushes afterthrowingdead leaves onto my face.Caughtin the toils of autumn,Itaste the brandy wind.Thecedar scent. The lump in the throat.Ittastes like heady salt of your skin.Elixirlessagain. Why? Itsmells like myrrh of your skin. Lara Biyuts © 2007

*play with us*

The play of hues beckoning outside. Twilight is purple, nearly sanguine. Veils aren't sanguine yet bold-- the yellow tinted vogue is kitschy. Red, ochre, green and topaz. The blond autumn plays boldly with the nature. Black is added to our cachepots. Some azure to the sky. Umbra and khaki of trees and filiage like scrolls of annals. The heady smells and airy cobwebs in thesunray. Ambergris of Kenzo and cinnamonunveiling someone's sins by scenting wrists. The autumn adorns you with needles of tweed.Lara Biyuts © 2011

http://rebekaharrington.com/2011/09/04/vampire-armastus/

Published on September 07, 2011 07:53

July 25, 2011

the mysterious date

Today is a birthday of Nina Berberova (1901-1993), the Iron Lady who was an author of the book of the other Iron Lady. Happy birthday to us and everyone who was born on 26 July !

As I wrote in my old blog on the blog.co.uk, in my life, I read a lot of published diaries, memoirs and letters written by historical persons or literary characters who lived in different times, and I always looked for the date 26 July in the notes, wishing to know what happened in the lives of my favorite writers and their personages on the day. But in vain. Without going into particulars, I never found this date; all the authors, as if on purpose, avoided mentioning of 26 July, and some of them omitted the very month July. Only in one novel by one English writer 26 July was the eve of an important, crucial event in the narrator's life. But that's not enough--that's why one of the main characters of my novel, the boy of the name of Jocelyn was born on 26 July.

Happy Birthday, our dear boy! Creates not one's will but one's imagination; the world is what we've made. Say to yourself: it's easy--and you'll make worlds and move all mountains. Your organs are all right: the heartbeat counts eternal motion, the lungs imperishable, the guts turns the carnal communion into energy and rejects all chemical waste. Prostate and liver, glandules and kindles, the concentration and altars of higher spheres, are consonant. No alarming signs or pain; your arms, your ears are all right, your mouth is moistened, your nerves are endurable and sound. If working hard, you are close to overtiring yourself, your subconsciousness will check you, on the instant. Beneficently tired, in the evening, you'll fall asleep till daybreak. The sound dreamless sleep will wash away all yesterday's troubles, recovering your balance, and you'll be cheerful and joyous like everyone when he is young, awakening at dawn, in springtime, overfilled with happiness; your friends, home, things of choice around; a wave is murmuring, the mountains are shining in the skyline. All what disturbed, angered, feared, all delusions, fears, offences glide sidelong, on background, like shadows, without disturbing your internal quietness. Be proud, wise and patient; love your takes-off and falls. Love both inflows and ebbs of happiness, both humans and the life in all diversity. Open your eyes and gulp the vivifying water of the elemental life, joyous and eternal.

The summer heat will moderate very soon, maybe on this very day, and everything will be all right again.

As I wrote in my old blog on the blog.co.uk, in my life, I read a lot of published diaries, memoirs and letters written by historical persons or literary characters who lived in different times, and I always looked for the date 26 July in the notes, wishing to know what happened in the lives of my favorite writers and their personages on the day. But in vain. Without going into particulars, I never found this date; all the authors, as if on purpose, avoided mentioning of 26 July, and some of them omitted the very month July. Only in one novel by one English writer 26 July was the eve of an important, crucial event in the narrator's life. But that's not enough--that's why one of the main characters of my novel, the boy of the name of Jocelyn was born on 26 July.

Happy Birthday, our dear boy! Creates not one's will but one's imagination; the world is what we've made. Say to yourself: it's easy--and you'll make worlds and move all mountains. Your organs are all right: the heartbeat counts eternal motion, the lungs imperishable, the guts turns the carnal communion into energy and rejects all chemical waste. Prostate and liver, glandules and kindles, the concentration and altars of higher spheres, are consonant. No alarming signs or pain; your arms, your ears are all right, your mouth is moistened, your nerves are endurable and sound. If working hard, you are close to overtiring yourself, your subconsciousness will check you, on the instant. Beneficently tired, in the evening, you'll fall asleep till daybreak. The sound dreamless sleep will wash away all yesterday's troubles, recovering your balance, and you'll be cheerful and joyous like everyone when he is young, awakening at dawn, in springtime, overfilled with happiness; your friends, home, things of choice around; a wave is murmuring, the mountains are shining in the skyline. All what disturbed, angered, feared, all delusions, fears, offences glide sidelong, on background, like shadows, without disturbing your internal quietness. Be proud, wise and patient; love your takes-off and falls. Love both inflows and ebbs of happiness, both humans and the life in all diversity. Open your eyes and gulp the vivifying water of the elemental life, joyous and eternal.

The summer heat will moderate very soon, maybe on this very day, and everything will be all right again.

Published on July 25, 2011 20:24

July 12, 2011

the link

"Ashes of the destroyed ancient temples knock in my heart." (me)

http://ethnikoi.org/persecutions.html

See more illustrations for the quotation:

"Ashes Klaas knocked in his heart." (Charles-Theodore-Henri De Coster (1827-1879)

"My father's sacred ashes I collected

Into a pouch to wear it on my chest,--

So that these ashes knocking at my chest

Kept calling me to vengeance and perdition!" (Eduard Bagritsky (1895-1934), translation is not mine.)

TILL ULENSPIEGEL. A Monologue 1,

poem

by Eduard Bagritsky

[ Note: The famous French writer Romain Rolland (1866-1944) wrote in his article, dedicated to Ulenspiegel: "Ulenspiegel is a Flemish Geus (a rebel against Spain), son of Claes, a skilled artisan, a freedom fighter and protector of his people. He avenges his people by using laughter, and he avenges his people by using a battle-axe." ]

They burned my father at the stake. Insane

My mother went from torture, and at that

In tears I abandoned my dear Damme.

My father's sacred ashes I collected

Into a pouch to wear it on my chest, —

So that these ashes knocking at my chest

Kept calling me to vengeance and perdition!

I travel wide: from Damme to Ostende,

And then to Antwerp from both Liège and Brussels.

With my fat Lamme we are riding donkeys.

I'm known to all: the ever-wandering fowler,

Who caged birds is carrying to the market;

The cantinière, who hands me with a smile

A mug of golden effervescent beer,

Accompanied by hot and juicy ham.

At city fairs I perform my songs

About Flanders and good old Brabant,

And all the Flemish feel down at their hearts,

Which long had grown fat and so much used to

The dreams of fragrant soups and amber beer,

The freedom spirit and the nation's pride.

I'm Ulenspiegel. There's no single village

Where I'd have not been to, no single town

Whose squares wouldn't have heard my ringing voice.

And Claes' ashes still tap at my heart,

I follow their beat by singing calmly

My lingering songs. In them will every Fleming

Discern the languid motion of the channels,

Where there are silence, swans, and wooden barges.

With comfortable fire in the hearth

Before him crackling gaily, he remembers

The hours of contentment, peace and languor,

When feeling tired of a day of work

He sniffs the smells of beer and roasted meat

While steeping in a lazy golden slumber.

I sing, "Hey, butchers, you don't need to kill

More calves and piglets! Choose a different stock.

A different prey awaits you. Stick your knifes

Deep into different animals. Their blood

Let spill onto your racks. Go stick those monks

And hoist them upside down like slaughtered pigs

Above your meat row counters for display."

And I go on, "Hey, blacksmiths, you don't need

To shoe workhorses and to mend saucepans!

Good battle swords and pointed spearheads

Are wanted now so much more than horseshoes,

Do slowly pour the streams of molten lead

Into the throats of ruddy, lardy monks,

It will be so much more to their taste

Than Burgundy or finest Xeres wine.

Hey, shipwrights, you don't need to build more boats

For carrying beer barrels to and fro.

Take seasoned timber: planks of pine and spruce,

Use braces of cast-iron and of steel

To build the liberation man-o'war!

The Flemish women for its sails shall weave

Of finest threads the whitest, strongest cloth,

And like a bull preparing for a fight

With an enraged pack of hungry wolves,

This battleship will put out to the sea,

Its canons pointing at the riotous coast."

And Claes' ashes still tap at my heart.

And my heart is now bursting, and my song

Acquires vehemence, and I am short of breath,

A burning sore comes closer to my tongue, —

I sing no more, but, like a vulture, wail,

"Hey, Flemish soldiers, for how long have you

Your steeds forgotten, striding in their stead

The public house benches? You don't need

To use your daggers just for cracking nuts,

Or with the spurs to scratch your itching heads

And reek of booze in vilest harlots' dens!

Lo! Swords are flashing, cities are aflame

Prepare for battle! The last hour has struck.

And everyone, who to lark's trill responds

With rooster's crow, is in our battle ranks.

The Duke of Alba!

This fight

Your fatal fall does portend;

The crop is ripe, and the reaper

The sickle on his sole does whet.

The tears of orphans and widows,

Which flow from their lifeless eyes,

Are weighing like drops of lead

On cups of the judgment scales.

The sword is our only hope,

In it our spirit trusts.

The skylark begins his song,

--The rooster returns the call.

(1922)

Published on July 12, 2011 00:12

ideology? history.

"Ashes of the destroyed ancient temples knock in my heart." (me)

http://ethnikoi.org/persecutions.html

See more illustrations for the quotation:

"Ashes Klaas knocked in his heart." (Charles-Theodore-Henri De Coster (1827-1879)

"My father's sacred ashes I collected

Into a pouch to wear it on my chest,--

So that these ashes knocking at my chest

Kept calling me to vengeance and perdition!" (Eduard Bagritsky (1895-1934), translation is not mine.)

TILL ULENSPIEGEL. A Monologue 1,

poem

by Eduard Bagritsky

[ Note: The famous French writer Romain Rolland (1866-1944) wrote in his article, dedicated to Ulenspiegel: "Ulenspiegel is a Flemish Geus (a rebel against Spain), son of Claes, a skilled artisan, a freedom fighter and protector of his people. He avenges his people by using laughter, and he avenges his people by using a battle-axe." ]

They burned my father at the stake. Insane

My mother went from torture, and at that

In tears I abandoned my dear Damme.

My father's sacred ashes I collected

Into a pouch to wear it on my chest, —

So that these ashes knocking at my chest

Kept calling me to vengeance and perdition!

I travel wide: from Damme to Ostende,

And then to Antwerp from both Liège and Brussels.

With my fat Lamme we are riding donkeys.

I'm known to all: the ever-wandering fowler,

Who caged birds is carrying to the market;

The cantinière, who hands me with a smile

A mug of golden effervescent beer,

Accompanied by hot and juicy ham.

At city fairs I perform my songs

About Flanders and good old Brabant,

And all the Flemish feel down at their hearts,

Which long had grown fat and so much used to

The dreams of fragrant soups and amber beer,

The freedom spirit and the nation's pride.

I'm Ulenspiegel. There's no single village

Where I'd have not been to, no single town

Whose squares wouldn't have heard my ringing voice.

And Claes' ashes still tap at my heart,

I follow their beat by singing calmly

My lingering songs. In them will every Fleming

Discern the languid motion of the channels,

Where there are silence, swans, and wooden barges.

With comfortable fire in the hearth

Before him crackling gaily, he remembers

The hours of contentment, peace and languor,

When feeling tired of a day of work

He sniffs the smells of beer and roasted meat

While steeping in a lazy golden slumber.

I sing, "Hey, butchers, you don't need to kill

More calves and piglets! Choose a different stock.

A different prey awaits you. Stick your knifes

Deep into different animals. Their blood

Let spill onto your racks. Go stick those monks

And hoist them upside down like slaughtered pigs

Above your meat row counters for display."

And I go on, "Hey, blacksmiths, you don't need

To shoe workhorses and to mend saucepans!

Good battle swords and pointed spearheads

Are wanted now so much more than horseshoes,

Do slowly pour the streams of molten lead

Into the throats of ruddy, lardy monks,

It will be so much more to their taste

Than Burgundy or finest Xeres wine.

Hey, shipwrights, you don't need to build more boats

For carrying beer barrels to and fro.

Take seasoned timber: planks of pine and spruce,

Use braces of cast-iron and of steel

To build the liberation man-o'war!

The Flemish women for its sails shall weave

Of finest threads the whitest, strongest cloth,

And like a bull preparing for a fight

With an enraged pack of hungry wolves,

This battleship will put out to the sea,

Its canons pointing at the riotous coast."

And Claes' ashes still tap at my heart.

And my heart is now bursting, and my song

Acquires vehemence, and I am short of breath,

A burning sore comes closer to my tongue, —

I sing no more, but, like a vulture, wail,

"Hey, Flemish soldiers, for how long have you

Your steeds forgotten, striding in their stead

The public house benches? You don't need

To use your daggers just for cracking nuts,

Or with the spurs to scratch your itching heads

And reek of booze in vilest harlots' dens!

Lo! Swords are flashing, cities are aflame

Prepare for battle! The last hour has struck.

And everyone, who to lark's trill responds

With rooster's crow, is in our battle ranks.

The Duke of Alba!

This fight

Your fatal fall does portend;

The crop is ripe, and the reaper

The sickle on his sole does whet.

The tears of orphans and widows,

Which flow from their lifeless eyes,

Are weighing like drops of lead

On cups of the judgment scales.

The sword is our only hope,

In it our spirit trusts.

The skylark begins his song,

--The rooster returns the call.

(1922)

Published on July 12, 2011 00:12

July 5, 2011

summertime

The Web--Cosmos--Afterlife.

The Photo

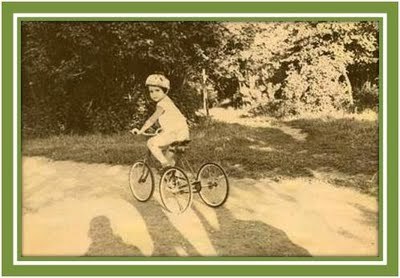

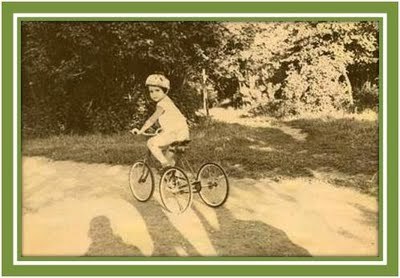

Nostalgia a killer, a tricky foe,

often using poetic license

to shape the past.

I'm trying to manage with it by myself.

But I miss you, and there's no help for it.

Do you remember…

Do you remember that sunny day,

impressed in the imperfect snapshot?

I am a child of three riding the tricycle.

You tell me to turn round, and there

your shade on the sand of the pathway,

a part of your shade,

the head and shoulders of a tall man

with the camera in hands over there

beside the shade of the whitethorn

in the nice public garden on the Left Bank.

Whitethorns, lilacs,

old lime-trees, phloxes,

gillyflowers.

What kind of bushes

at the background of the picture?

Lilacs, as far as I remember.

By the time of the snapshot,

the lilacs have stopped blooming,

and the time of lime-trees has come,

the time when my birthday approaches.

Do you remember?

And now, when I write this,

it's June-July again. The summer heat.

Pictures of the past rise before my mind.

Is there any use to talk with the dead?

Yes, there is,

if only I could believe in possibility of the talk.

The Web--Cosmos--Afterlife.

*from the Land of Cast-Iron Snowdrops with love*

The Photo

Nostalgia a killer, a tricky foe,

often using poetic license

to shape the past.

I'm trying to manage with it by myself.

But I miss you, and there's no help for it.

Do you remember…

Do you remember that sunny day,

impressed in the imperfect snapshot?

I am a child of three riding the tricycle.

You tell me to turn round, and there

your shade on the sand of the pathway,

a part of your shade,

the head and shoulders of a tall man

with the camera in hands over there

beside the shade of the whitethorn

in the nice public garden on the Left Bank.

Whitethorns, lilacs,

old lime-trees, phloxes,

gillyflowers.

What kind of bushes

at the background of the picture?

Lilacs, as far as I remember.

By the time of the snapshot,

the lilacs have stopped blooming,

and the time of lime-trees has come,

the time when my birthday approaches.

Do you remember?

And now, when I write this,

it's June-July again. The summer heat.

Pictures of the past rise before my mind.

Is there any use to talk with the dead?

Yes, there is,

if only I could believe in possibility of the talk.

The Web--Cosmos--Afterlife.

*from the Land of Cast-Iron Snowdrops with love*

Published on July 05, 2011 23:37

June 26, 2011

lesser known quotes

"…the wondrous herb of the name of Freedom grows there."

(Nikolai Przhevalsky)

Plea for help:

The snatch (above) is all I've remembered hearing the long beautiful quotation on TV in the end of one French documentary about Nikolai Przhevalsky. If anyone has a source where the full phrase could be found, please let me know.

Below, there are several excerpts from his Notes and Diaries which are web-accessible to me and which are notes of an explorer and scientist mainly, from which I simply snatched some digressions whose theme is the same as that of the firs quotation (above) that is Freedom.

Note:

The famous explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky (1839-1888), who had been a national hero by his death day, always went for his expeditions (financed by the national government) being attended by detachment of soldiers (Cossacks) and his young lover, an army-officer who was assigned as a guard commander and who was of Przhevalsky's own choice. (See: "Dream of Lhasa: The Life of Nikolay Przhevalsky (1839-88 Explorer of Central Asia)", by Donald Rayfield.)

Nan-Shan. Summer, 1879.

"…Meanwhile, the hunter gradually has ascended nearly up to the eternal snows. The glorious view of the morning sun lit mountains spreads underneath his feet. Both the yaks and naurs are forgotten for the time being. All eyes, you are engulfed with the magnificent view. Your heart is light and free, on this height, on this staircase to heaven, as you are face to face the grandiose nature, far from all the worldly vanity and filth. At least for minutes, you become a true spiritual thing, separated from the mundane petty thoughts and wishes…"

Ussuri krai. 1867-1869.

"The final act of my stay at Ussuri krai was the expedition in summer 1869, in the western and southern part of the Khanka Lake basin, in search of new roads, by water as well as by land.

For three months, I have traveled over the forests, mountains and valleys, sometimes by water, and I'll never forget the time spent among the wild virgin nature that breathed with all the charm of the springtime and summer life. It was often that a day long I had not other abode than the sky above, other furniture than the fresh verdure and flowers, not hearing other sounds than the birds' singing that enlivened the meadows, marshlands and forests."

"Those were wondrous charming days, full of freedom and pleasures! Often, so often I recall the life now, and I can say that every man, who's ever tasted the freedom of wilderness, cannot forget of it afterwards even living a most comfortable life…"

"…Walking a little more, I paused and began watching the view before my eyes, seeking to engrave it upon my memory. Impressions and images began flashing in my mind… Two years of the life of a wanderer had glided like a night dream full of wonderful visions… Khanka, farewell! Ussuri krai, farewell! Maybe I'll never see your endless forests, magnificent waters and your rich virgin nature again, but I'll always be recalling your name and the happy days of the free wandering life."

from "Mystery of Lop (Nur) Lake". 1878, March 31.

"From Kenderlyk we went to the Zaisan outpost in order to go to Petersburg from there. Camels and the expedition inventory remain keeping in Zaisan. I mean to return in the following springtime and then, with new strength and new luck, to begin the new expedition."

"I'm 39 today, and the day is celebrated by the ending of the expedition, though not so triumphant as my previous travel over Mongolia. By now, the work has done only half: Lop Lake is explored, but Tibet remains unexplored. For the fourth time I've not been able to reach it: for the first time it was when I returned from Blue River; then--from Lop Lake; for the third time--from Ghu-Chen; finally, for the fourth time, the expedition has been stopped in the beginning.

But I don't give up! Next springtime, as soon as my health is all right again, I shall set out again."

"Although the stoppage of the work is not my fault and I realize that it is the best under the current circumstances and with the state of my health, but I feel sad going back. The day long before, I was not quite myself and even weeping. Even my upcoming return to my estate doesn't gladden too much.

True, life of a traveler has many adversities, but it gives so many happy moments, unforgettable for ever.

The absolute freedom and business to your liking, that's the beauty of travels. Travelers never forget their hard work time afterwards, even when they use the best and most comfortable advantages of civilized life.

And now, farewell, my happy life, but not for long! The year will pass, the misunderstandings with China will be settled, my health will be all right again, and then I shall take my staff of wanderer again, and again I shall go to the Asian wilderness."

(translation is mine.)

The End

but

It's not over. It'll never be over... :)

(Nikolai Przhevalsky)

Plea for help:

The snatch (above) is all I've remembered hearing the long beautiful quotation on TV in the end of one French documentary about Nikolai Przhevalsky. If anyone has a source where the full phrase could be found, please let me know.

Below, there are several excerpts from his Notes and Diaries which are web-accessible to me and which are notes of an explorer and scientist mainly, from which I simply snatched some digressions whose theme is the same as that of the firs quotation (above) that is Freedom.

Note:

The famous explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky (1839-1888), who had been a national hero by his death day, always went for his expeditions (financed by the national government) being attended by detachment of soldiers (Cossacks) and his young lover, an army-officer who was assigned as a guard commander and who was of Przhevalsky's own choice. (See: "Dream of Lhasa: The Life of Nikolay Przhevalsky (1839-88 Explorer of Central Asia)", by Donald Rayfield.)

Nan-Shan. Summer, 1879.

"…Meanwhile, the hunter gradually has ascended nearly up to the eternal snows. The glorious view of the morning sun lit mountains spreads underneath his feet. Both the yaks and naurs are forgotten for the time being. All eyes, you are engulfed with the magnificent view. Your heart is light and free, on this height, on this staircase to heaven, as you are face to face the grandiose nature, far from all the worldly vanity and filth. At least for minutes, you become a true spiritual thing, separated from the mundane petty thoughts and wishes…"

Ussuri krai. 1867-1869.

"The final act of my stay at Ussuri krai was the expedition in summer 1869, in the western and southern part of the Khanka Lake basin, in search of new roads, by water as well as by land.

For three months, I have traveled over the forests, mountains and valleys, sometimes by water, and I'll never forget the time spent among the wild virgin nature that breathed with all the charm of the springtime and summer life. It was often that a day long I had not other abode than the sky above, other furniture than the fresh verdure and flowers, not hearing other sounds than the birds' singing that enlivened the meadows, marshlands and forests."

"Those were wondrous charming days, full of freedom and pleasures! Often, so often I recall the life now, and I can say that every man, who's ever tasted the freedom of wilderness, cannot forget of it afterwards even living a most comfortable life…"

"…Walking a little more, I paused and began watching the view before my eyes, seeking to engrave it upon my memory. Impressions and images began flashing in my mind… Two years of the life of a wanderer had glided like a night dream full of wonderful visions… Khanka, farewell! Ussuri krai, farewell! Maybe I'll never see your endless forests, magnificent waters and your rich virgin nature again, but I'll always be recalling your name and the happy days of the free wandering life."

from "Mystery of Lop (Nur) Lake". 1878, March 31.

"From Kenderlyk we went to the Zaisan outpost in order to go to Petersburg from there. Camels and the expedition inventory remain keeping in Zaisan. I mean to return in the following springtime and then, with new strength and new luck, to begin the new expedition."

"I'm 39 today, and the day is celebrated by the ending of the expedition, though not so triumphant as my previous travel over Mongolia. By now, the work has done only half: Lop Lake is explored, but Tibet remains unexplored. For the fourth time I've not been able to reach it: for the first time it was when I returned from Blue River; then--from Lop Lake; for the third time--from Ghu-Chen; finally, for the fourth time, the expedition has been stopped in the beginning.

But I don't give up! Next springtime, as soon as my health is all right again, I shall set out again."

"Although the stoppage of the work is not my fault and I realize that it is the best under the current circumstances and with the state of my health, but I feel sad going back. The day long before, I was not quite myself and even weeping. Even my upcoming return to my estate doesn't gladden too much.

True, life of a traveler has many adversities, but it gives so many happy moments, unforgettable for ever.

The absolute freedom and business to your liking, that's the beauty of travels. Travelers never forget their hard work time afterwards, even when they use the best and most comfortable advantages of civilized life.

And now, farewell, my happy life, but not for long! The year will pass, the misunderstandings with China will be settled, my health will be all right again, and then I shall take my staff of wanderer again, and again I shall go to the Asian wilderness."

(translation is mine.)

The End

but

It's not over. It'll never be over... :)

Published on June 26, 2011 01:34

June 19, 2011

some dark poetry

Sonnet LXXI

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell:

Nay, if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it, for I love you so,

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O! if,--I say you look upon this verse,

When I perhaps compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse;

But let your love even with my life decay;

Lest the wise world should look into your moan,

And mock you with me after I am gone.

(Shakespeare)

In An Empty House

From the walls the paper's blue is vanished,

The daguerreotypes, the ikons banished.

Only there the deepened blue appears

Where these hid it, hanging through the years.

From the heart the memory is perished,

Perished all that long ago it cherished!

Those remain, of whom death hides the face,

Leaving their yet unforgotten trace.

(Ivan Bunin, (1870–1953))

Memory

When, for the mortal one, is stilled the noisy day,

and, on the silent city's buildings,

the easy shadow of night is softly laid,

and sleep--the prize for daily grindings,

then in the silent air they painfully drag on--

my hours, sleepless ones and endless:

bites of the remorse-snake, in my heart, stronger burn

in night's unquestionable blankness.

My fancies boil. My mind, under a pine,

is overfilled with meditations;

remembrance silently, before sad eyes of mine,

unrolls its scroll in lines' successions.

And reading with despite the life, I had before,

I curse the world, and tremble, breathless,

and bitterly complain, and shed my tears sore,

but…

I don't obliterate

the awful

lines of sadness.

(A. Pushkin, (1799–1837))

"Now Dry Thy Eyes"

Now dry thy eyes, and shed no tears.

In heaven's straw-pale meadows veers

Aquarius, and earthward peers,

His emptied vessel overturning.

No storming snows, no clouds that creep

Across the sheer pure emerald steep,

Whence, thinly-drawn, a ray darts deep

As a keen lance with edges burning.

(Mikhail Kuzmin, (1872–1936))

Love's Reason Why

For beauty love me not!

Nor love for gold!

For beauty—love the Day—

For wealth—love coinage cold!

Nor love me for my youth!

For Youth—love spring!

But love—because to you

With constant love I cling.

(Konstantin Romanov (aka K.R.) (1858–1915))

Published on June 19, 2011 00:25