android obesity

Introduction

“Of Human Bondage”. This essay is an excerpt in my historical “Through the Baltic Looking-Glass”, Part 6. Reading it, please, keep in mind that the notes are written in 1912 (that is,101 years before the historical was designed by the author and cyber-mentioned in 2011). Place: the Russian Empire. Narrator: an observant glob-trotter and autocar-hater of the name of Oscar Maria Graf. The main personage of my latest historical, he is a second-self of my novel’s main personage (whose writings is the historical), and not mine. (A novel inside another).

Of Human Bondage

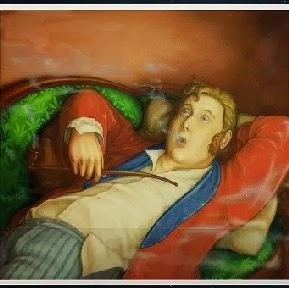

Among human vices, there is the only that suggests much good about its bearer, in case if the human is not too ugly, not looking like an oaf. I’m talking of sloth, and the remembrance of my prodigious elder contemporary Oscar Wilde made me launch into this digression on Sloth, one of the deadly sins. Laziness. Idleness. “Idleness is the root of all evil.” I believe not. Scarcely offsprings like Thievery and Cruelty could come from this particular root. To steal, in the literary sense of the word, in other words, to get into somebody else’s apartments through small casements or chimney, to jump from a crowded horse-drawn tram on the move with somebody else’s purse in hand and to spend hours walking up and down the back staircases in search of a proper doorway, Man should have an exceptional capacity for work. A mere cruelty demands much effort. An intention to do a nasty trick to anybody demands special knowledge, long walk for elaborating a plan of the nasty trick, innumerable phone calls, typewriting denunciations, and visits, after all, in the fifth and sixth floors of buildings with no lift. A salesman of match factory is equal to the task rather than lazybones.

I love the kind of sloth, which is low-key like our fine ear for music and eternal as birthmark, and Man even takes pride in it at heart. Blossoming in Oblomovist’s infancy, the Sloth is flowering for the rest of his life. Lazybones, idlers and other sluggards, I’ll call them “Oblomovists” in this digression, the renowned proponent or archetype of Oblomovism. A “lazy, apathetic person.” Apropos, as my reader knows, Oblomov was good-looking and of noble birth, that’s why my remark about a look of an oaf.

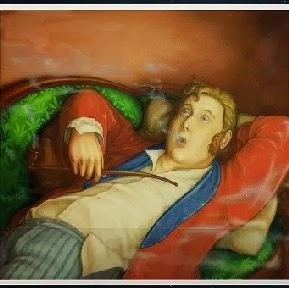

It’s interesting to watch Oblomovosts. When Oblomovist subsides in a chair, in public, his eyes and every fold of his coat tells about a mental monologue like this: “Why do you badger me, all of you? Do I disturb anyone? Leave me alone, please…” He dreams about especially big flypaper, at his room door, for strangers as well as his friends.

Oblomovists are exceptionally constant in affairs of the heart. A love affair is a labour, one of hardest, sometimes, and however fast the scud of centuries, however strong time subjugates all to the capitalist system, nobody ever hit upon an idea of a fair division of labour in this ticklish sphere, inventing a conveyer, at least, like those at a small cannery. One cuts a sardine’s head, another throws it to oil, the thirds prepares a tin, and so on, till the label is attached and the tinned sardines are ready for usage. At a love’s labour, one has to do everything by himself. If there was a “division of labour” in it, the last in the process, the one who attached a label, could be a man who elopes with somebody else’s bride three months after the wedding. Oblomovist falls in love only three times in his lifetime, that’s why he’s called a one-woman man. For the first time, aged 12, he falls in love out of lack of experience; for the second time, aged 18, he falls in love out of solidarity with his palls in love. If he ever falls in love again, he does it at 30 to 40, and it’s his third and final time, which destines him to a lamentable end: he brings a young entity into his home, with him peering into the future in state of a special meek fear and quiet passivity usual for some heroines of Greek tragedies and heroes of Shakespeare at the moments of their temporary weakness or hesitation. Too sublime to be described. And then, the Oblomovist falls in love never again. His first romantic experience introduces him to the tormenting sense of the unshared love with the loud glee and intense curiosity from everybody: friends, relatives, strangers and eyewitnesses. His the second time, he enjoys the shared love with all its tormenting appendages: leaving home, the duty to wait at the box office, outpourings to his beloved one’s relatives, and defence of her virtues before his own relatives. All this is for better to obese men, who feel determined to lose some weight by means of sudden shocks and long-distance races. For the Oblomovist, all this is but a burden. In the course of his third and final love affair, it’s clear to him that Love looks much like those registration forms, in which Man must put his name, surname, and a few formalities more – address, or something. With knowledge like this, Oblomovist cannot become disloyal. In his view, adultery is a ghastly bill, which must be paid with his own blood and flesh:

(1) the first acquaintance – two encounters at their friends’ (the horse-drawn tram, the seventh floor, the four-hour talk), the box, and care of it;

(2) developing the acquaintance -- his invention of a special meetings for his wife, a place for rendezvous;

(3) terms of intimacy – supper at restaurant and taking home (the overdone hazel-grouses, tainted caviar, his return home at 4 a.m., and the long taking off his boots at the door);

(4) tender passion – his search for cheap brooches and hurried stopping rumors, scenes at home, his wife’s strange and alarming look and behavior;

(5) coolness before parting -- the encounter with his old friend Stolz and his week-long thinking over Stolz’ tone when both of them were at his beloved woman’s drawing-room;

(6) “let’s forget each other!” -- his prompt and cheerful doing his wife’s small commissions (cleaning gloves, browsing lampshades, search for an inexpensive dressmaker) for the sake of quietude at home.

Present this bill (above) to Oblomovist at the moments, when he is about to know a good-looking woman better, and he repels it with a plaintive cry of a tormented soul and puts the image of the good-looking woman out of his head for ever. In case if he doesn’t repel the bill, then he is not Oblomovist but a tailor’s apprentice with curved legs and everlasting care about new commissions beyond his strength.

The most of Oblomovists are wise men, because they have plenty of time for thinking over anything occurs him.

A man of expansive nature usually thinks over his action a long while after he did it. “You know,” the man says, “I shouldn’t call Dermott swine… Especially, in public, and to his face. It appears, he never wrote that letter…” or he simply runs about the room, grabbing every thing on his way, and eventually finding a harbour for his hands – his own head – he begins pulling at it, and crying out: “What an idiot I am!.. I’m stupid… stupid!.. The embezzlement! Why did I do it?!.. Grabbed the money, lost it, lied that I spent the day at work, and as a result, spent the night at the porter’s…”

Oblomovist, on the contrary, ponders all, even what he is not about to do. Being too late to a theater show, when lying on his divan, he imagines how many small misfortunes he could get from his four-hour observance of somebody else’s pretence, pretentiousness, stupidity and vanity, and he rises from the divan with relish, which is much more intensive than that in case of his return home after the theatre show. As a result: the reasonable economizing and the chance to go to bed earlier tonight.

Every Oblomovist is prepared for all vagaries of life, because at leisure he has thought over everything – an unexpected and enormous legacy, hard to be calculated even by the best accountants of St Petersburg, and a sluggard rapidly turning into a French aviator, and an unexpected collapse of a building with the ground would swallowing it up – everything, right up to a need to grow big blue wings for flying from one housetop to another.

Every Oblomovist is always an excellent reader. Every author’s dream reader. Taking a book in hands, he elicits all what the author and publisher wanted to give for one ruble and a half, unlike the other readers. Take as an example an active, hard-working man, who uses fifteen kopeks at most of a three-ruble book. Learning of the main character’s name and the fortune of the main character’s father, and learning from the last page of a place of the main character’s last rest place, the active reader lightheartedly goes out for personal reasons. Why do men like that read fiction? Books for them should be written by beat policemen and not by men of letters: certificate of birth fist, then certificates of graduation from school, compulsory vaccinations and previous convictions, and finally, the properly signed death certificate. Oblomovist reads every book with great relish. He realises that after he reads it through, he has to start another work. As the very thought of a new work is hateful as such, he rereads the book till he feels certain that the author keeps from him nothing of the underlying theme and no one word.

However, there are hours, even days, when Oblomovists get active and mobile. Auto-mobile. It’s the time when he goes to rent an apartment, for really, our accommodation along with every component is a vital base for our Sloth.

An active, hard-working man is quick looking for an accommodation and he doesn’t waste time taking it. “What, my divan cannot be placed here? And I’ll place it in the next room. A draught here, you say? When? Always?.. Well, that’s odd!.. However, I’m always busy. I simply have no time to watch draughts… The window is too small, you say? And I’ll place it in… I cannot?.. Never mind. Who could I bid a bargain here?”

Oblomovist is observant and thrifty: “If I want to open the window, I’ll have to stand up, go round the table and remove the armchair… You seem to offer me a penal servitude with the two-year contract and not an apartment. 50 rubles for six rooms with firewood? Happiness is not in firewood. Where will I place my divan? Here?! Do you believe one of my hands is two-meter long?.. To stand up every time I need a cigarette and to go to the table?.. God forbid! Sorry to disturb you.” However, if he rents an apartment, he insists on his arrival before his furniture is brought there. He sits down on a windowsill and patiently waits till the apartment is furnished and completely prepared for living.

Oblomovists are gentle. A human’s heart can be hardened and soul embittered by meetings, talks, intrigues, mingling in society. While contemplating life in the silence of his study, Oblomovist is protected from all the factors of emotional and moral bitterness.

Oblomovist readily listens to outpourings from an enamoured person, because the person is in need of verbal response alone, and Oblomovist may not rise from his chair to give it, with other cases known when a man, merely hurting his leg against a cab, insists on his listener’s kneeling and careful examination of a big blear blot of a bruise over his bared, pale and hairy leg – fancy that!

Oblomovist loves talking of flowers, springtime and beauty of sunrises, because nobody ever had thought of arguing on the indisputable subjects and he may not stand up to take an encyclopedia in hands and dig for several articles in the heavy volume, humiliating both himself and the encyclopaedia, which as though was made to maintain somebody’s ignorance and shallowness. Generally speaking, one should not ever start arguing. Especially, about some important and burning issues that demand meditations. If your companion is a learned and respected man, you should not think that he could get resolved on changing his all views after your fifth sentence. If your companion is a youngster, who argues solely in virtue of his pubertal age, it’s ridiculous to pretend a house of reformation and improve young minds. Oblomovists never start arguing.

I like their look and manner, and I’m often nice to them -- not those who have big flabby paunches and eyes closed with fat, and who can get exited only at table when anticipating the third remove – no, others, those, who even work, from time to time, or always bear burden of career and vanity, and who always have the same dream shining between their eyelids and vibrating in their hearts: “Ah! If only I could leave all! To drive everybody away, to take a seat and to have a rest for two or three years… in order to do nothing socially useful or of public utility!..” When I see men with the unrealizable dream in eyes, I feel sad. Maybe, because I myself would like to live, doing nothing socially useful from a utilitarian point of view. Why? Because I am one of them, most likely.

(the end of the excerpt)

Lara Biyuts ©

“Of Human Bondage”. This essay is an excerpt in my historical “Through the Baltic Looking-Glass”, Part 6. Reading it, please, keep in mind that the notes are written in 1912 (that is,101 years before the historical was designed by the author and cyber-mentioned in 2011). Place: the Russian Empire. Narrator: an observant glob-trotter and autocar-hater of the name of Oscar Maria Graf. The main personage of my latest historical, he is a second-self of my novel’s main personage (whose writings is the historical), and not mine. (A novel inside another).

Of Human Bondage

Among human vices, there is the only that suggests much good about its bearer, in case if the human is not too ugly, not looking like an oaf. I’m talking of sloth, and the remembrance of my prodigious elder contemporary Oscar Wilde made me launch into this digression on Sloth, one of the deadly sins. Laziness. Idleness. “Idleness is the root of all evil.” I believe not. Scarcely offsprings like Thievery and Cruelty could come from this particular root. To steal, in the literary sense of the word, in other words, to get into somebody else’s apartments through small casements or chimney, to jump from a crowded horse-drawn tram on the move with somebody else’s purse in hand and to spend hours walking up and down the back staircases in search of a proper doorway, Man should have an exceptional capacity for work. A mere cruelty demands much effort. An intention to do a nasty trick to anybody demands special knowledge, long walk for elaborating a plan of the nasty trick, innumerable phone calls, typewriting denunciations, and visits, after all, in the fifth and sixth floors of buildings with no lift. A salesman of match factory is equal to the task rather than lazybones.

I love the kind of sloth, which is low-key like our fine ear for music and eternal as birthmark, and Man even takes pride in it at heart. Blossoming in Oblomovist’s infancy, the Sloth is flowering for the rest of his life. Lazybones, idlers and other sluggards, I’ll call them “Oblomovists” in this digression, the renowned proponent or archetype of Oblomovism. A “lazy, apathetic person.” Apropos, as my reader knows, Oblomov was good-looking and of noble birth, that’s why my remark about a look of an oaf.

It’s interesting to watch Oblomovosts. When Oblomovist subsides in a chair, in public, his eyes and every fold of his coat tells about a mental monologue like this: “Why do you badger me, all of you? Do I disturb anyone? Leave me alone, please…” He dreams about especially big flypaper, at his room door, for strangers as well as his friends.

Oblomovists are exceptionally constant in affairs of the heart. A love affair is a labour, one of hardest, sometimes, and however fast the scud of centuries, however strong time subjugates all to the capitalist system, nobody ever hit upon an idea of a fair division of labour in this ticklish sphere, inventing a conveyer, at least, like those at a small cannery. One cuts a sardine’s head, another throws it to oil, the thirds prepares a tin, and so on, till the label is attached and the tinned sardines are ready for usage. At a love’s labour, one has to do everything by himself. If there was a “division of labour” in it, the last in the process, the one who attached a label, could be a man who elopes with somebody else’s bride three months after the wedding. Oblomovist falls in love only three times in his lifetime, that’s why he’s called a one-woman man. For the first time, aged 12, he falls in love out of lack of experience; for the second time, aged 18, he falls in love out of solidarity with his palls in love. If he ever falls in love again, he does it at 30 to 40, and it’s his third and final time, which destines him to a lamentable end: he brings a young entity into his home, with him peering into the future in state of a special meek fear and quiet passivity usual for some heroines of Greek tragedies and heroes of Shakespeare at the moments of their temporary weakness or hesitation. Too sublime to be described. And then, the Oblomovist falls in love never again. His first romantic experience introduces him to the tormenting sense of the unshared love with the loud glee and intense curiosity from everybody: friends, relatives, strangers and eyewitnesses. His the second time, he enjoys the shared love with all its tormenting appendages: leaving home, the duty to wait at the box office, outpourings to his beloved one’s relatives, and defence of her virtues before his own relatives. All this is for better to obese men, who feel determined to lose some weight by means of sudden shocks and long-distance races. For the Oblomovist, all this is but a burden. In the course of his third and final love affair, it’s clear to him that Love looks much like those registration forms, in which Man must put his name, surname, and a few formalities more – address, or something. With knowledge like this, Oblomovist cannot become disloyal. In his view, adultery is a ghastly bill, which must be paid with his own blood and flesh:

(1) the first acquaintance – two encounters at their friends’ (the horse-drawn tram, the seventh floor, the four-hour talk), the box, and care of it;

(2) developing the acquaintance -- his invention of a special meetings for his wife, a place for rendezvous;

(3) terms of intimacy – supper at restaurant and taking home (the overdone hazel-grouses, tainted caviar, his return home at 4 a.m., and the long taking off his boots at the door);

(4) tender passion – his search for cheap brooches and hurried stopping rumors, scenes at home, his wife’s strange and alarming look and behavior;

(5) coolness before parting -- the encounter with his old friend Stolz and his week-long thinking over Stolz’ tone when both of them were at his beloved woman’s drawing-room;

(6) “let’s forget each other!” -- his prompt and cheerful doing his wife’s small commissions (cleaning gloves, browsing lampshades, search for an inexpensive dressmaker) for the sake of quietude at home.

Present this bill (above) to Oblomovist at the moments, when he is about to know a good-looking woman better, and he repels it with a plaintive cry of a tormented soul and puts the image of the good-looking woman out of his head for ever. In case if he doesn’t repel the bill, then he is not Oblomovist but a tailor’s apprentice with curved legs and everlasting care about new commissions beyond his strength.

The most of Oblomovists are wise men, because they have plenty of time for thinking over anything occurs him.

A man of expansive nature usually thinks over his action a long while after he did it. “You know,” the man says, “I shouldn’t call Dermott swine… Especially, in public, and to his face. It appears, he never wrote that letter…” or he simply runs about the room, grabbing every thing on his way, and eventually finding a harbour for his hands – his own head – he begins pulling at it, and crying out: “What an idiot I am!.. I’m stupid… stupid!.. The embezzlement! Why did I do it?!.. Grabbed the money, lost it, lied that I spent the day at work, and as a result, spent the night at the porter’s…”

Oblomovist, on the contrary, ponders all, even what he is not about to do. Being too late to a theater show, when lying on his divan, he imagines how many small misfortunes he could get from his four-hour observance of somebody else’s pretence, pretentiousness, stupidity and vanity, and he rises from the divan with relish, which is much more intensive than that in case of his return home after the theatre show. As a result: the reasonable economizing and the chance to go to bed earlier tonight.

Every Oblomovist is prepared for all vagaries of life, because at leisure he has thought over everything – an unexpected and enormous legacy, hard to be calculated even by the best accountants of St Petersburg, and a sluggard rapidly turning into a French aviator, and an unexpected collapse of a building with the ground would swallowing it up – everything, right up to a need to grow big blue wings for flying from one housetop to another.

Every Oblomovist is always an excellent reader. Every author’s dream reader. Taking a book in hands, he elicits all what the author and publisher wanted to give for one ruble and a half, unlike the other readers. Take as an example an active, hard-working man, who uses fifteen kopeks at most of a three-ruble book. Learning of the main character’s name and the fortune of the main character’s father, and learning from the last page of a place of the main character’s last rest place, the active reader lightheartedly goes out for personal reasons. Why do men like that read fiction? Books for them should be written by beat policemen and not by men of letters: certificate of birth fist, then certificates of graduation from school, compulsory vaccinations and previous convictions, and finally, the properly signed death certificate. Oblomovist reads every book with great relish. He realises that after he reads it through, he has to start another work. As the very thought of a new work is hateful as such, he rereads the book till he feels certain that the author keeps from him nothing of the underlying theme and no one word.

However, there are hours, even days, when Oblomovists get active and mobile. Auto-mobile. It’s the time when he goes to rent an apartment, for really, our accommodation along with every component is a vital base for our Sloth.

An active, hard-working man is quick looking for an accommodation and he doesn’t waste time taking it. “What, my divan cannot be placed here? And I’ll place it in the next room. A draught here, you say? When? Always?.. Well, that’s odd!.. However, I’m always busy. I simply have no time to watch draughts… The window is too small, you say? And I’ll place it in… I cannot?.. Never mind. Who could I bid a bargain here?”

Oblomovist is observant and thrifty: “If I want to open the window, I’ll have to stand up, go round the table and remove the armchair… You seem to offer me a penal servitude with the two-year contract and not an apartment. 50 rubles for six rooms with firewood? Happiness is not in firewood. Where will I place my divan? Here?! Do you believe one of my hands is two-meter long?.. To stand up every time I need a cigarette and to go to the table?.. God forbid! Sorry to disturb you.” However, if he rents an apartment, he insists on his arrival before his furniture is brought there. He sits down on a windowsill and patiently waits till the apartment is furnished and completely prepared for living.

Oblomovists are gentle. A human’s heart can be hardened and soul embittered by meetings, talks, intrigues, mingling in society. While contemplating life in the silence of his study, Oblomovist is protected from all the factors of emotional and moral bitterness.

Oblomovist readily listens to outpourings from an enamoured person, because the person is in need of verbal response alone, and Oblomovist may not rise from his chair to give it, with other cases known when a man, merely hurting his leg against a cab, insists on his listener’s kneeling and careful examination of a big blear blot of a bruise over his bared, pale and hairy leg – fancy that!

Oblomovist loves talking of flowers, springtime and beauty of sunrises, because nobody ever had thought of arguing on the indisputable subjects and he may not stand up to take an encyclopedia in hands and dig for several articles in the heavy volume, humiliating both himself and the encyclopaedia, which as though was made to maintain somebody’s ignorance and shallowness. Generally speaking, one should not ever start arguing. Especially, about some important and burning issues that demand meditations. If your companion is a learned and respected man, you should not think that he could get resolved on changing his all views after your fifth sentence. If your companion is a youngster, who argues solely in virtue of his pubertal age, it’s ridiculous to pretend a house of reformation and improve young minds. Oblomovists never start arguing.

I like their look and manner, and I’m often nice to them -- not those who have big flabby paunches and eyes closed with fat, and who can get exited only at table when anticipating the third remove – no, others, those, who even work, from time to time, or always bear burden of career and vanity, and who always have the same dream shining between their eyelids and vibrating in their hearts: “Ah! If only I could leave all! To drive everybody away, to take a seat and to have a rest for two or three years… in order to do nothing socially useful or of public utility!..” When I see men with the unrealizable dream in eyes, I feel sad. Maybe, because I myself would like to live, doing nothing socially useful from a utilitarian point of view. Why? Because I am one of them, most likely.

(the end of the excerpt)

Lara Biyuts ©

Published on December 08, 2013 06:39

No comments have been added yet.