Tucker Lieberman's Blog

July 2, 2021

‘Now Departing From Track 1’: Introduction to ‘Ten Past Noon’

Ten Past Noon: Focus and Fate at Forty, published in 2020, is Tucker Lieberman’s hybrid nonfiction work about “war, racism, gender, time, mortality, free will, money, argument, information architecture, and why a writer might not finish a book.” Now, you can read the introduction, which explains what fuel the train runs on. I’m pleased to share the introduction online, and I hope you’ll be curious about the rest of the book, too.

June 18, 2021

‘There’s this constant rising and falling’: A conversation with Daniel Bailey

I interviewed Daniel Bailey about his new poetry book, A Better Word for the World, published by Apocalypse Party (2021).

First, listen to him read a couple poems from the book:

Daniel Bailey reads his poem: “Landscape in Urgent Care”Daniel Bailey reads his poem: “The Unplanned Upon Morning”

When did you know you had an idea for a collection, and what was it like putting it together?

This is a book that came together over a period of about seven years. The poems were written in spurts that ranged from several days to several weeks to several months. These periods of writing typically produced poems that were formally and tonally similar. The earliest, including the section starting with “Orb-Weaver,” happened in a night on which I gave myself a piece of paper laid out on the floor for each poem, and I moved from page to page, adding a line at a time. Another couple sections (first and third) were written over a longer period of time. The original intent was for these sections to be their own, shorter collection, which I was calling National Dust Day. These poems were written on copy paper with a sharpie, in all caps, and with no line breaks. The intention was to slow down my thought and compose one liners and non-sequiturs and purely be a vessel of uninhibited thought. Later, I opened a Google doc titled “waterfalls” and mostly wrote into that to complete the remainder of the book. Not long after, I realized that the result of “waterfalls” and everything else felt like it all belonged together, and it became A Better Word for the World.

I sense a range of emotions, even just moving from line to line within the same poem. When you think of this collection, is there one particular feeling that stands out for you in your memory?

I’ve always been a big fan of Poe’s concept of “unity of effect,” even though I definitely stray from the intended effect. I’ve always wanted my poems to move the reader into uncharted psychological and emotional territory through an embrace of any emotion that might imbue a line and build unique contrasts. While Poe may have been writing toward melancholy in one piece and horror in another, my aims are vaguer. It’s that trance-like feeling that I get when I really let language control me.

The section beginning “Orb-Weaver” has nine poems which are tied together by woodland scenes with a lake or a river. Water is also mentioned throughout the rest of the book. The river reminds me of the book’s cover. How did you decide to use this central image of water?

I just love water. I love drinking it. I love wading in it. I love thinking about it. I hate when people capture it in pools and torture it with chlorine. Every one of my river memories is positive. Last year, I told a friend I had finished a book of poetry. He said, “Oh yeah, what’s it like?” I said, “It’s like my poems, I guess. It’s about rivers and the water cycle and whatnot,” which is not all it is, but you read it correctly that I was thinking a lot about rivers. I just love them. They’re calming to me. I prefer a good river to the ocean. I love how water is so essential to life and that there’s this constant rising and falling. We would die without it. It’s the ultimate drama that most people aren’t really thinking about on a day-to-day basis. For a moment, I wanted to title the book The Evaporator and the cover could’ve been a picture of me mimicking Jackson Brown on the cover of The Pretender. When I approached a close friend about potential titles, they told me they’d be more inclined to read a book called A Better Word for the World over a book called The Evaporator. I like both titles, so I don’t know if that was a moment of weakness. Maybe.

Your poem “I Was a Swamp” begins: “In a previous life, I was a swamp / and now in this life driving into a large city / feelings like driving into the internet.” I read this poem as describing a double loss: the swamp was perhaps unfairly perceived as an impure, compromised body of water to begin with, and now there’s no nature left at all, just guilt and alienation. Is there any way to go back and reclaim the swamp?

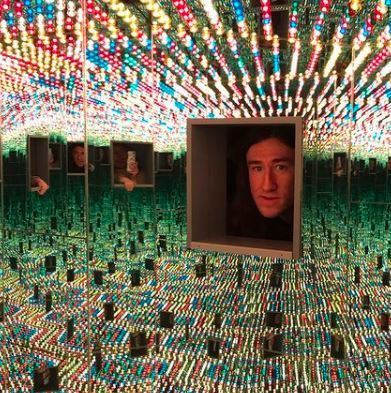

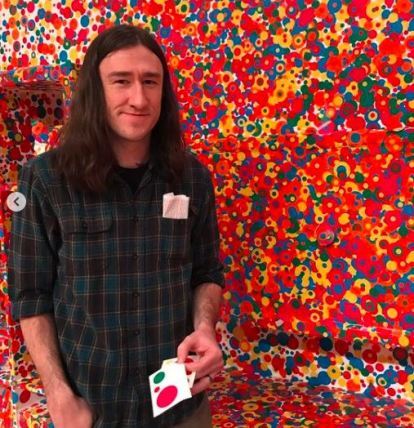

I think that loss of the swamp came from learning about all the man-made threats facing the Everglades. I liked the contrast between swamp and city and the idea of a reincarnation that can be something much broader than the movement of a soul from one biological body to another. I don’t know about reclaiming swamp. Ecologically, I think once a swamp is gone, it’s gone. There’s just the memory of it. I imagine many people would view swamps as dirty (impure) and inhospitable (to humans) environments, which is a big part of the reason I think they’re cool. I need to get to the Everglades at some point. Composition-wise, I actually started this one in the Notes app while riding in my parents’ car through the interstates of Atlanta on the way to the High Museum of Art to see Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrors.

Some poems address a “you,” as in “The Evaporator,” which imagines your own sudden death and says: “And now you sit here / with these words that do not exist / And yet all seasons simultaneously greet you”. Who is the “you”? Are you addressing yourself in a detached way, or are you speaking to someone else? Maybe the reader?

I’ve always viewed “you” as the most flexible of all the pronouns. In the context of a poem or song, it has such an inviting aura for both the reader and the poet (as well as any other “character” of the poem). My poems definitely fall in line with Keats’ concept of negative capability, and my use of “you” is a huge part of how that plays out. I don’t find myself to be a very interesting person, so the possibilities allowed by the imagination and by the plasticity of language are the biggest factors as to why I write poetry and not fiction.

Do you have a favorite poem in this collection, or one that feels like the heart of the collection?

I mentioned earlier that I had strongly considered “The Evaporator” to be a titular poem. It’s easily the poem that I have the fondest memory of in terms of composition. What I did was I folded several pieces of copy paper together and drove to a nearby park that straddles the Middle Oconee River. I slowly walked through the park, writing a line or two at a time, just whenever a new line revealed itself to me. Then I went and wrote the poem “Worry Stone,” whose first line contains the book’s actual title. I mentioned the Jackson Browne album/song earlier, but I came up with the title long before writing the poem and coming up with the silly Jackson Brown concept (glad I didn’t do that). I had recently read Kafka’s short story “In the Penal Colony,” which largely revolves around an officer of said penal colony describing, in great detail, a machine built solely to torture and kill prisoners. It’s a really gripping and horrifying story, but I loved the idea of writing a poem that rigorously described a machine, though with a less grisly purpose. I couldn’t figure out what kind of machine that would be, so I decided to write the title on the front of the makeshift copy paper book and forced myself to live up to it. What resulted was easily my favorite hour of writing that I’ve ever experienced, even though it doesn’t even attempt to describe a machine called the evaporator.

What do you want readers to bring to their experience of this collection or take away from it?

I think I can mirror a previous answer: the one where I brought up Poe’s “unity of effect.” I think the ultimate reward would be to know that the reader came out of a poem feeling something impossible to name, something new. Something that would have to have a different name for anyone that feels it. In his book Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema, Andrei Tarkovsky says, “When I speak of poetry I am not thinking of it as a genre. Poetry is an awareness of the world, a particular way of relating to reality.” I really relate to that idea. I write poems to relate to the world and discover new portals of being. I hope that my poems allow the reader to do the same.

Who are your poetic influences?

My poetry sprang from writing songs in my bedroom as a teenager, so definitely songwriters, especially Dave Berman and Bill Callahan. Eventually, I started writing more when I went to college and couldn’t afford the privacy to write songs and not have people complain about the noise. It was in an introduction to poetry class taught by Peter Davis that I really discovered that poetry was my thing. Peter Davis is a unique poet. He showed me that a poem can do just about whatever it wants.

As far as poets, Frank O’Hara and Frank Stanford are probably the biggest: Stanford for his propulsive energy, darkness, and motion. And O’Hara for showing me that it’s ok to write in the way that one speaks. My influences are pretty eclectic, and they really can’t be limited to poetry. I’ve felt inspired by James Tate, Aase Berg, Heather Christle, Jason Bredle, Molly Brodak, Sam Pink, Blake Butler, Jennifer L. Knox. I could name so many.

I also feel very inspired by cinema, particularly the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, who I mentioned earlier, and Werner Herzog for his dedication to “ecstatic truth.”

Will you be able to do any in-person readings this year?

Yes! I won’t be doing a reading tour or anything that extravagant, though. My friend Laura Theobald (who also designed the cover to A Better Word for the World) has a poetry book called Salad Days set to release from Maudlin House in September. I read it last year when Laura and I exchanged manuscripts during the early part of the pandemic. It’s very good. We both live here in Athens, Georgia, so she asked me to read at her release party. So, I’m excited about that, especially since various life situations have prevented me from doing my own thing. And I’m not an extremely social person, so that will probably be the first “normal” thing I do since before March last year. At the moment, details aren’t set, other than that it will occur in Athens, but I look forward to it.

Check out the book: A Better Word for the World. You can find the author on Neutral Spaces and Twitter.

May 30, 2021

‘Don’t use YOU’: Writing advice from a high school paper on Shakespeare

Reviewing one of my high school papers I saved from over two decades ago, in which I discussed King Lear, I note my original paragraph:

Some people are able to maintain their goodwill to others despite personal insult and tragedy. Edgar says, ‘[I,] by the art of known and feeling sorrows, / am pregnant to good pity.” The context is not optimistic, but his philosophy is clear, and it is more promising than the idea that people are born evil and misfortunate. Edgar says that when bad things happen to you, you can make something good out of something bad or at least grow as a person.

The teacher’s feedback in red pen on that last sentence: “Don’t use you.”

The teacher was correct. “You” was a bit too informal here, especially as my paper about human nature was otherwise written in third person.

But when my inner self-critic finger-wags at me, even today, “Don’t use you,” I’d do well to remember where this teacherly advice came from. It was shorthand advice that applied to a specific paper. It may or may not apply to whatever I’m writing today.

“…when bad things happen to you, you can make something good out of something bad…”

April 4, 2021

Poems read Jan-Mar 2021

Kaveh Akbar, “What Use is Knowing Anything if No One is Around“

Anna Akhmatova, [“I have a lot of work to do today…“] (trans. Judith Hemschemeyer)

John Ashbery, “Of the Light,” [“But how does this work?“] from The New Spirit

Ruth Awad, “Inventory of Things Left Behind“

Daniel Bailey, “Drunk Sonnet 17“

Gabrielle Bates, “Ownership“

Rosa Alice Branco, “Prescriptions for the Soul” (translated by Alexis Levitin)

Lucie Brock-Broido, “Domestic Mysticism“

William Bronk, “Weathers We Live In“

Paul Celan, “From Darkness to Darkness,” in 70 Poems, tr. Michael Hamburger

Wanda Coleman, “Black-Handed Curse”, “What He Gave Me“

Robert Creeley, “The Movie Run Backward“

Mahmoud Darwish, from In the Presence of Absence

Deborah Digges, [“Many doors are set open…“] in Rough Music

Alex Dimitrov, “Weldon Kees“

Katie Ford, [“Yet I see the small lights…“]

Vievee Francis, “The Heart Will Scale the Dew”

Deborah Garrison, “On New Terms”

Jenny George, “Reprieve,” “Origins of Violence” in The Dream of Reason

Aracelis Girmay, [“praise the water, now“]

Louise Glück, “Landscape” “Copper Beech“

Ray Gonzalez, “Hummingbird on the Porch“

Jorie Graham, “Notes on the Reality of the Self“

Linda Gregg, “The Presence in Absence“

Rachel Eliza Griffiths, “About the Flowers”

Alen Hamza, “Where love naps, there nip I“

Jane Hirshfield, “Like Others”

Kim Hyesoon, “Heart’s Seashore,” translated by Don Mee Choi

Pamílèrín Jacob, “My Dad says to write things I want from/with God in 2021”

Denis Johnson, “Night”

Dynas Johnson, “black girl recovers water goddess for her future daughter“

Weldon Kees, “Small Prayer”

donika kelly, “Love Poem: Werewolf,” in Bestiary

Jane Kenyon, “Song“

Sarah Kirsch, “Winter music” (translated by Anne Stokes)

Katherine Larson, “Statuary“

Philip Levine, “Let Me Begin Again”

Larry Levis, “Gossip in the Village“

Paige Lewis, “The Terre Haute Planetarium Rejected My Proposal“

Sandra Lim, “Pastoral“

Ada Limón, “What I didn’t know before“

Derek Mahon, “Heraclitus on Rivers“

Gretchen Marquette, “Elsewhere“

Jane Mead, “Trans-Generational Haunting”

Valerie Mejer Caso, “Watering the Geraniums in the Window,” in the Edinburgh Notebook

WS Merwin, “The Present”

Dunya Mikhail, “The New Year“

Czesław Miłosz, “A Song on the End of the World“

John Murillo, “Variation on a Theme by Elizabeth Bishop”

Hieu Minh Nguyen, “The New Decade”

Sarah O’Brien, “Once I Dreamt of Falling & Woke Up on the Floor“

Sharon Olds, “Amaryllis Ode,” “Bestiary“

Patrick Phillips, “Living,” in Boy

Alejandra Pizarnik, “[Who does not believe…]”

Hajara Quinn, “Corsage“

Camille Rankine, “Necessity Defense of Institutional Memory”

Adrienne Rich, “Song,” [“Since we’re not young…“]

Patrick Rosal, “Ten Years After My Mom Dies I Dance“

James Schuyler, “The Snow“

Charif Shanahan, “Where If Not Here (II)“

Soren Stockman, “Skirmanté“

Mark Strand, “Fiction“

Arthur Sze, “Pitch Blue” in The Glass Constellation

James Tate, “‘The Whole World’s Sadly Talking to Itself’,” “Interruptions”

Jean Valentine, “When she told me”

G. C. Waldrep, “Mutter Museum with Owl,” in The Earliest Witnesses

Philip Whalen, [“Torn paper fake mountains“]

Charles Wright, “Still Life with Spring and Time to Burn“

Adam Zagajewski, “Transformation,” “Try to Praise the Mutilated World,” translated by Claire Cavanagh

March 24, 2021

‘How Pharaoh Tried to Steal the Exodus’

For Passover, I wrote a rhyming poem in the style of Dr. Seuss’ “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” It’s called “How Pharaoh Tried to Steal the Exodus.” The link I provided here will get you through the paywall. At the top of the article, there’s a link to a SoundCloud recording that will open in a new window and play you my 9-minute narration of the poem, in case you’d like to listen while you read with the text. Hey, if you don’t need the transcription and just want the direct link to the SoundCloud, there you go.

Enjoy the holiday! Let quarantines not take rhyming poetry, at least, away from us.

March 17, 2021

‘Trans-Galactic Bike Ride’ is a Lambda finalist!

On Monday, Lambda Literary announced the 2021 finalists! Who’s on the list? Stellar work from a lot of great authors, and I’m honored to tell you that Trans-Galactic Bike Ride: Feminist Bicycle Science Fiction Stories of Transgender and Nonbinary Adventurers made the list! (I have a short story, “Lucy Doesn’t Get Angry,” in this anthology.)

Ebooks and print books are available internationally from Microcosm. In the US only, you can order print copies from Bookshop. If you’re not ready to place an order, just mark it as “Want to Read” on Goodreads so that you will find it again someday when you circle back around the galaxy. But please consider how cool it will be to be holding copies of all five finalists in the Transgender Fiction category when one of them is announced as the winner on June 1!

2021 Lambda Literary Award finalists – Transgender Fiction

Finna , Nino Cipri, Tordotcom Publishing The Seep , Chana Porter, Soho Press The Subtweet , Vivek Shraya, ECW Press The Thirty Names of Night , Zeyn Joukhadar, Atria BooksTrans-Galactic Bike Ride: Feminist Bicycle Science Fiction Stories of Transgender and Nonbinary Adventurers, Lydia Rogue, Microcosm Publishing

Trans-Galactic Bike Ride

Trans-Galactic Bike Ride

March 14, 2021

‘The Elephant’: A poem about authenticity

Today I learned about Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s poem “The Elephant,” translated from the Portuguese by Richard Zenith in the collection Multitudinous Heart. The translation of this poem is also available online.

“I make an elephant,” the poet says, repurposing “some wood / from old furniture” and stuffing it “with cotton, / silk floss, softness.” Glue, too, will have to do. But what to do about the ivory, “that pure white matter / I can’t imitate”? What to do about the eyes, “the most / fluid and permanent / part of the elephant”?

It’s not so much an external object. The elephant is “my dearest disguise,” the poet says. He is constructing himself.

It is a poem that might appeal especially to anyone who has tried to sculpt or reconstruct their own body, and perhaps it also may, more abstractly, address the sculpting or reconstructing of nonphysical aspects of a life.

It’s about the risk that we do it badly. We don’t meet our own standards, or the world is not ready to receive us and believe in us. The elephant enters “a jaded / world that doesn’t believe / anymore in animals / and doubts all things,” and “no one will look / at him, not even to laugh / at his tail.” It’s also about monstrosity: how an attempt to imitate an awesome, beautiful being may result in a half-invisible, ugly accident that inevitably must be disassembled by its creator as a failed experiment. Or: This is, at least, part of the process that others pick up on when they perceive us as monsters.

February 6, 2021

What’s a ‘commonplace book’?

“For nearly four decades, I’ve kept what’s known as a commonplace book,” Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times in November 2020. “It’s where I write down favorite sentences from novels, stories, poems and songs, from plays and movies, from overheard conversations. Lines that made me sit up in my seat; lines that jolted me awake. About once a year, I’ll say something I think is worthy of inclusion. I mostly end up deleting those entries.”

I have always done this, too, since I was 18. In my first year of college, in 1998, I started my own website as a hobby, and I began filling it with my own mini-essays (“blogs” were not quite invented yet) and interesting passages that I found in library books and typed up. As my list of quotations grew, I grouped them by theme; and as the lists continued to grow, the themes multiplied and became more specific.

“Do you keep a notebook?” Prof. Lance Morrow asked my essay-writing class in my journalism program in 2004. He explained to the class that he meant writing down personal musings and interesting passages written by others that might fuel our own future essays. I answered that I did; I had multiple “notebooks,” organized by theme. (The class seemed to think this was a little over the top.) Also, my “notebooks” have always been digital, so that the information is readily searchable by keyword and copy/pasteable in case it needs to be reorganized or, at long last, incorporated into an essay of my own. (I do sometimes use paper and pen to transcribe information, but ultimately I type it up because that’s how it will be more usable.)

In 2020, I counted the number of themed files. There are two hundred. They include:

abortion, abstractions, activism, affluenza, altruism, animals, anxiety, art, attention and busyness, beliefs, bias and control, body, brain, caring, Cartesianism, celibacy, certainty, chance, charm, cheating, climate change, cloning, coaching, commercialism, compassion, conformity, creativity, death penalty, decision-making (and gut instinct), dialogue, dirt, disaster insurance, disgust, domination of nature, emotions, enlightenment, environment, epiphany, eternal now, ethics (business), evolution, faith-based charities, false memory and confession, food (and hunger), forgiveness, free speech, free will, friendship, gender, giving, God (and: anthropomorphism, atheism, biblical authority, faith, feminist theology, “on your side,” and “knows secrets”), grief, hair, handicapping agreements for games, healing, history, honor, human rights, humanism, humility, humor, immortality, integrity, Internet history, interpellation, Israel, Jewish, journalism, knowledge (and not knowing, deliberate ignorance, and ridiculous beliefs), language, liberty and security, literacy and numeracy, logic, love, lying (and rationalization), marijuana, marriage, math, memory (and the permanence of Internet publication), mind, money, monsters, mortality, myth (and political myths), names, natural disasters, “nature or nurture,” networks, nostalgia, oaths, organ transplant, Orwell, Panopticon, paradox, patriotism, peace, philosophy, pleasure, poaching, political polarization, politics (and unwritten norms), prayer, prisoners, procreation and parenting, prohibition of alcohol, race, regret, relationships, relativism (this one, dear reader, may be the longest, at 70,000 words), religion and science, religious experience, risk, ritual, saying no, self, self-sacrifice, sexuality, shame, skill, sleep, software design and testing, soldiers, solitude, success, suicide, technology, Thanatos, theodicy, time, tolerance, tree, trust, twee, utilitarianism, vegan, virtue signaling, weapon metaphors, werewolves, writing

Plus, of course, the indispensable catch-alls: “nice turns of phrase” and “miscellaneous.”

If I’m writing an essay and I suddenly remember a phrase I was once struck by, I can search any of these files (or my entire computer) by keyword. Then I can cite it in what I’m currently writing.

I recently told someone that I organize my digital files like this, and she asked if it was difficult to come up with these themes and stick to the organizational system. No, I answered. The themes were born from need, and they developed organically, as when one begins with a messy room and begins labeling the shelves as a response to appropriately accommodate all the material that already exists. Also, I stick to it only insofar as it works. I put the material on the “most correct” shelf because where else would I put it? So I use my files appropriately, and thus they work for me.

If I started with a blank slate, now, at age 40, my labels for these files would be completely different. They are what they are because they spun off of a system I kicked off, semi-consciously, when I was 18 and just starting to make a big proto-literary mess.

I suppose I could restructure everything, but there seems to be no urgent need to do so. And this would be a huge project; how would I begin to approach the 70,000-word file labeled “relativism,” a book-length document comprised entirely of other people’s statements on this subject?

The benefit of keeping the “old ways” is that they are embedded deeply in my brain. When I’m reading and a quote strikes me, I don’t have to ask myself, “Which of 200 themes is this best categorized under?” I already know “what I want the quote for”; my “themes” are just my shorthand keywords for something I already implicitly recognize and understand. It is a private, decades-long conversation I have with myself.

I didn’t know this was called a “commonplace book” until I saw Dwight Garner’s essay in 2020. It feels like a commonplace activity within my own life because I’ve always done it. I don’t know if others consider it a normal thing to do. I have never had any other word for it. Sometimes I write “QUOTES” at the top of a piece of paper so that I know the material has to be typed up. Apart from that, it has been a nameless activity for me.

January 27, 2021

Poems read Oct-Dec 2020

Poems that stumbled across my path online. You might like them, too.

Lisa Ampleman, “Gilding the Lily”

Molly Brodak, “Ok“

William Bronk, “Deus Vobiscum”, “Questions for Eros,” “The Remains of a Farm”

Jericho Brown, “Another Elegy,” in The New Testament

Lauren Clark, “Illinois in Spring”

Lucille Clifton, “birth-day”

Cid Corman, “The Unforgivable”

Gregory Corso, “Hello”

Ansel Elkins, “Autobiography of Eve“

Rhina P. Espaillat, “November”

Jack Gilbert, “Exceeding the Spirit”

Aracelis Girmay, “[strange earth, strange]”

Peter Gizzi, “The Present is Constant Elegy“

Louise Glück, “The Pond,” in The House On Marshland

Linda Gregg, “God’s Places”

Paul Guest, “Post Factual Love Poem”

Alen Hamza, “Someday I Will Learn”

Joy Harjo, “She Had Some Horses”

Zbigniew Herbert, “Prayer”

Amorak Huey, “Lifespan of a Deer”

Laura Jensen, “Memory,” “Here in the Night”

Jean Joubert, “Brilliant Sky” (tr. Denise Levertov)

Dilawar Karadaghi, “[I’m not here]”

Joanna Klink, “On Mercy”

Ada Limón, “Instructions on Not Giving Up”

Moira Linehan, “My Great Blue”

Timothy Liu, “Survivors”

Audre Lorde, “Speechless“

Sophia de Mello Breyner, “[You will never again feel]”

W. S. Merwin, “The Morning”, “How It Happens”

Malena Mörling, “Ashes“

Sharon Olds, “I Cannot Say I Did Not”

Mary Oliver, “Fall Song,” in American Primitive

Charles Olson, “[I measure my song]”

George Oppen, “Psalm”, “World, World–“

Katherine Osborne, “[My son died.]”

Linda Pastan, “In This Season of Waiting,” “Go Gentle”

Rowan Ricardo Phillips, “Grief and the Imaginary Grave”

Rainer Maria Rilke, “[Only in our doing can we grasp you]” in The Book Of Hours

Theodore Roethke, “Memory”

Charif Shanahan, “Ligament“

Natalie Shapero, “Not Horses,” in Hard Child

Izumi Shikibu, “[You ask my thoughts]” tr. Hirshfield & Aratani

Charles Simic, “Poem” [Every morning I forget how it is]

Maggie Smith, “Rain, New Year’s Eve”

Tracy K. Smith, “An Old Story”

Molly Spencer, “Most Accidents Occur At Home”

Matt Stefon, “A bent rainbow”

Timmy Straw, “Willamette”

Anna Swir, “Her Death is In Me” (tr. Milosz and Leonard Nathan)

Fiona Sze-Lorrain, “[Nothing in my song]”

Shuntaro Tanikawa, “Twenty Billion Light Years of Loneliness” trans. Wright

Chase Twichell, “Fox Bones”

Jean Valentine, “The One You Wanted to Be Is The One You Are”

diane wakoski, “the moon has a complicated geography”

Katharine Whitcomb, “Through the Window,” in The Daughter’s Almanac

Wendy Xu, “[Most things lose]”

January 25, 2021

On sun, shadow, and hidden images (three quotes)

Digital art by Tucker Lieberman.

Digital art by Tucker Lieberman.“In Pharaonic Egypt at the time of Akhnaton, in a now-extinct monotheistic religion that worshiped the Sun, light was thought to be the gaze of God. Back then, vision was imagined as a kind of emanation that proceeded from the eye. Sight was something like radar. It reached out and touched the object being seen. The Sun—without which little more than the stars are visible—was stroking, illuminating, and warming the valley of the Nile. Given the physics of the time, and a generation that worshiped the Sun, it made some sense to describe light as the gaze of God.”

—Carl Sagan. Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium. Ballantine, 1998. p. 31.

“Here is a graphic demonstration of what Jung usefully called the work of the archetypal shadow: we cannot encounter directly what we have repressed, what we cannot face, because it is by definition unconscious; and so we encounter it indirectly, as if it were outside us, cast like a shadow out of the unconscious on to the world.”

—Patrick Harpur. The Philosopher’s Secret Fire: A History of the Imagination (2002). Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003. p. 54.

“It could be that I had the kind of childhood full of absences, and yours happened to be the only one that hurt so good. It could be simply that suicide does tricky things to people. It is a bizarre kind of loss, full of answers and empty of ways to access them, much like the series of Magic Eye posters taped to the walls of our junior high school. Despite extended periods of squinting and eye-crossing, I repeatedly failed to detect the hidden images, available only to those with the ability to skew their vision. I grew to detest those posters with their cloaked dinosaurs and sailboats, constant reminders of the limits of my perception.”

—Candace Jane Opper. Certain and Impossible Events. Tucson, Arizona: Kore Press, 2021. p. 13.