Brian Clegg's Blog, page 77

March 6, 2015

Teachers - go forth and demo!

When I talk to scientists who want to write a popular science book rather than a textbook, there are two connected differences I emphasize - narrative and drama. A textbook can be just a collection of facts, but that's anathema to the popular science audience. Narrative steals some of the tools of fiction, both on the small scale and in giving the book as a whole a narrative arc. And drama gives tension and excitement.

When I talk to scientists who want to write a popular science book rather than a textbook, there are two connected differences I emphasize - narrative and drama. A textbook can be just a collection of facts, but that's anathema to the popular science audience. Narrative steals some of the tools of fiction, both on the small scale and in giving the book as a whole a narrative arc. And drama gives tension and excitement.Some scientists and historians of science have always complained about the use of drama. 'It wasn't really like that,' they moan. 'It wasn't one person against the world, coming up with a great idea, it was a team effort, building incrementally on other's work.' Well, yes, to a point. But as long as you don't trample on facts, I think an element of drama is essential, and it can usually be found, even if it has to be given slightly more prominence than it really had.

When giving a talk about science, these two factors are equally important - and the opportunity for drama is so much greater, because it's not just in the information, it can be in the way the information is put across. At its most basic, it's about presentation style - not reading from notes in a monotone. But also there's the chance to the demonstrate. If you take a look at this video of my Dice World talk (don't worry, no need to watch it all!):

... the first thing I do is give away a free book. Not a conventional 'demonstration' but something active, rather than just talking. Then from 2:40 to to about 6 minutes I do a little demonstration involving flipping a coin. It doesn't contribute hugely to the information content of the talk, but from feedback, it's something the audience really appreciates. Later on, I get the audience standing up and partaking in an experiment, and when I finish with the Monty Hall problem, I don't just describe it, I run the gameshow. And it really helps.

So if you're a science teacher or technician, you've got something in your armoury that can easily add drama to lessons. Demonstrations aren't always used as much as they once were, partly because of the strictures of the curriculum and partly because of Health and Safety (my brother-in-law, a former head of chemistry did manage to get the building evacuated with one of his better demonstrations). But we forget demonstrations at our peril.

Those nice people at British Science Week have come up with a cunning plan to get more demonstrations happening. They want to make the Thursday of Science Week (19 March) 'Demo Day' when you can pledge to make a demo in return for a prize draw that includes a wifi microscope - can't be bad! And they've got some excellent video resources giving demonstration ideas (don't just show the video, that misses the point). Why not pop over to the Demo Day web page and take a look.

I'll just finish of with a video they made last year called Demo Day, The Movie:

Published on March 06, 2015 02:58

March 5, 2015

Quantum quackery

One reaction to my writing

The Quantum Age

is that the number of emails I receive based on a sort of 'quantum mysticism' has doubled. This is where the jargon of quantum theory is applied recklessly, without any of the background science, to imply that something strange and wonderful can happen... because it's 'quantum'.

One reaction to my writing

The Quantum Age

is that the number of emails I receive based on a sort of 'quantum mysticism' has doubled. This is where the jargon of quantum theory is applied recklessly, without any of the background science, to imply that something strange and wonderful can happen... because it's 'quantum'.I recently had this article on the website of the 'Committee for Skeptical Inquiry' with the same name as my current post brought to my attention. It is rather dated, as it was written 17 years ago, but much of it holds up. A lot of blame is laid at the door of Fritjof Capra's popular book, The Tao of Physics, which draws parallels with aspects of quantum theory and Eastern mysticism (though to be fair to Capra, he doesn't the extra step, made by many New Agers, of going from parallels to assumed causality).

The author of the CSI piece, Victor Stenger, is very blunt in his dismissal of anything mystical, if not mysterious, about quantum theory. He was a physics professor, but the view he gives in this article is not 100% what I'd regard as mainstream physics. He is so enthusiastic to get rid of any possible weirdness that he plays down some aspects. This comes across particularly strongly when he merges the concepts of quantum entanglement and wave function collapse. He says, for instance, that Einstein called wave function collapse 'spooky action at a distance', but that was a reference to quantum entanglement, a phenomenon that does indeed allow the kind of instant communication at a distance that Stenger is at such efforts to dismiss, although admittedly it is a not a mechanism that allows the communication of non-random information, as there is no way of controlling what is 'transmitted'.

Stenger also seems to dismiss the Feynman path integral approach, commenting that quantum behaviour can be understood 'without discarding the commonsense [sic] notion of particles following definite paths in space and time.'

What we have here, I think, is almost an inverse of Capra. Just as Capra could sometimes be a bit loose with making something of parallels that didn't mean anything, Stenger is so determined to show that quantum physics really isn't strange but is 'common sense' that he overplays the idea that quantum theory is really just good old classical physics with a few bells and whistles.

However much I find the Stenger piece irritating, though, there is no doubt (as often seems to be the case with skeptics with a 'k') he is doing the wrong thing for the right reason. Because there are plenty of people trying to deceive others by claiming all sorts of quantum holistic hogwash. Just because something has a probabilistic component, and seems weird to common sense, as quantum theory certainly does, it does not follow that everything weird is valid. There is no scientific basis for using quantum theory to justify magic.

We know that there are some quantum effects in biology - and it's just possible, despite Stenger's firm denial, that quantum physics plays a role in human consciousness (though it's relatively unlikely, as quantum effects dislike warm and wet conditions). But there is no firm evidence to date for quantum physics underlying strange psychic abilities or medical magic. Unlike a skeptic with a k, I don't dismiss these possibilities out of hand - there is slight, though certainly not definitive, evidence for at least one aspect of ESP (see my Extra Sensory ). But even if such abilities were definitively proven, there is no basis as yet for saying that quantum physics has any role to play. And its relevance certainly can't be deduced from any mystical mumbo jumbo.

So, unless it's used in a scientific context*, beware 'quantum' like the plague.

* With the exception of uses where it is not intended to portray weird mysticism, such as the Bond film Quantum of Solace, or Finish Quantum dishwasher tablets, which actually work quite well.

Published on March 05, 2015 00:45

March 4, 2015

No, I don't want a super car experience, thank you

Every now and then I get a semi-spam email (i.e. something I probably accidentally signed up to receive, but never really wanted) offering me the opportunity to buy cut-price 'treats', like a super car experience. I know some people love this kind of thing, but I just don't get it.

Every now and then I get a semi-spam email (i.e. something I probably accidentally signed up to receive, but never really wanted) offering me the opportunity to buy cut-price 'treats', like a super car experience. I know some people love this kind of thing, but I just don't get it.I've got three problems with the whole 'super car experience' thing. (If your mind is heading back to the early Gerry Anderson series, illustrated here, which I loved as a boy - our Ford Anglia was excellent for playing Supercar, as the heater controls made an excellent substitute for the throttles, and it even had little wings on the tail - I am not referring to Supercar, but rather an 'experience' day where you get to drive something like a Ferrari or an Aston Martin.)

My first issue is that I wouldn't actually want one of these cars as they are incredibly impractical (anyone remember the Top Gear where they tried to get 3 out of an underground car park in Paris?), ludicrously expensive and make a silly noise. I've never understood the appeal of the sort of noise boy racers try to imitate by having a dustbin in place of an exhaust pipe on their Ford Fiesta. It sounds loud, nasty and industrial. My favourite car noise is an electric car - but that's a different story.

The second problem is that they wouldn't just give you the keys and say 'Have fun,' they would expect you to drive it around a track, with experts looking on and sniggering at your inability to 'take the correct line' or brake at the sweet spot, or G spot or whatever it is. I did once accidentally go to a track day, and quite enjoyed being driven around by an expert (scary though it was), but there was no way I was going to do it myself, in front of others.

Most importantly, though, if I did have a drive in a super car (and if I did, it would be an Aston Martin, no question), it would have to be my own. I don't understand the envy-driven gratuitous excitement of having a go at something you can't actually have. It's a phenomenon that's quite closely related to pornography, perhaps most closely in those house porn 'Escape to the Country' style house programmes where people who are selling a 3 bed semi in London look round 10 bathroom mansions in the country, which normal people could never afford, so they watch the programme to drool instead. It's one of the nastiest aspects of capitalism.

So there you have it. Super car experiences are for those whose existence is unsatisfactory. Get, as they say, a life.

Published on March 04, 2015 00:32

March 3, 2015

Making experiments (some on your own brain) come to life

There has been a significant amount of noise on Twitter and elsewhere about 'The Dress', the phenomenon of a photograph of a dress which it is claimed that some people see as black and blue, and others as white and gold. My suspicion is that this is a hoax - a very nice piece of PR.

There has been a significant amount of noise on Twitter and elsewhere about 'The Dress', the phenomenon of a photograph of a dress which it is claimed that some people see as black and blue, and others as white and gold. My suspicion is that this is a hoax - a very nice piece of PR.The reason I am suspicious is that I've seen pictures on different sites where I see it as each of the colours (and the pictures are different at the RGB level)*. But if it were genuine, it would simply be demonstrating how false the image of the world we think we see through our eyes really is.

This was one of the points I wanted to demonstrate when writing The Universe Inside You . In its predecessor, Inflight Science , I included a series of science experiments that the reader could do on a plane. It was a bit harder to do something similar with TUIY, where I wanted to show things from optical illusions, with a reveal of what was happening, to demonstrations of a Crookes radiometer and the early 'artificial intelligence' program ELIZA.

In the end I put together a website to accompany the book which has the experiments on it, often as videos. When 'The Dress' came up, I immediately thought of a couple of the demonstrations on there - the experiments include both an optical and an auditory illusion. So if you want to do a little experimenting with the universe (and your brain), take a look at the Universe Inside You website.

*ADDED: HT to Stuart Cantrill for pointing out that some people see the same image differently at different times, and that two people looking at the same image at the same time can get different results - so it isn't all a hoax. But there certainly are many mocked up versions in the Twittersphere etc. which definitely are fixed.

Published on March 03, 2015 01:19

March 2, 2015

Lost and found in translation

I was reminded at the weekend of the apparent translating boo-boo that resulted in Cinderella's very impractical glass slippers. Allegedly, in the original French, she had slippers that were 'vair' - made very sensibly (if you don't belong to PETA) of fur. However, the translator was clearly having a bad day, and just as I tend to merrily type 'there' instead of 'their' when I'm tired, he or she read this as the similar sounding 'verre' - meaning glass. (Sadly, according to Snopes, this is unlikely to be true - HT to Matthew Surnameunknown for pointing this out. I still suspect there was something in it, though.)

I was reminded at the weekend of the apparent translating boo-boo that resulted in Cinderella's very impractical glass slippers. Allegedly, in the original French, she had slippers that were 'vair' - made very sensibly (if you don't belong to PETA) of fur. However, the translator was clearly having a bad day, and just as I tend to merrily type 'there' instead of 'their' when I'm tired, he or she read this as the similar sounding 'verre' - meaning glass. (Sadly, according to Snopes, this is unlikely to be true - HT to Matthew Surnameunknown for pointing this out. I still suspect there was something in it, though.)So far, so amusing. But then it made me think of my books.

My various titles have been translated into a good few languages, and for all I know they could be replete with interesting changes of meaning. Of course they were translated by good, professional translators, but even so slip-ups can occur.

As it happens I know this for certain, by taking a quick look at my biography in the German translation of 'Instant Egghead Guide to Physics', which becomes 'Physik für Eierköpfe'.

I'm not sure where they got it from, as there isn't a biography in the English version, but if you take a look at this snippet from my website, you don't need to be a German speaker to spot what's wrong in the first line of the German version:

I know that's more a transcription error than a translation problem - an error that could occur even in an English version, but at least with English texts I see the proofs and can correct them.

There are now rather a lot of translations out there, as the picture below indicates, with a good few more in production as we speak. With most, frankly, I haven't a clue, and my rusty school French and German would be little help in attempting to spot any errors even in those relatively familiar languages.

So what is the moral of all this? There may be errors, but there's not a lot I can do about them (unless an eagle-eyed reader sends me an email). That being the case, it's best not to say anything. After all, it is best not to be rude to a translator. They have an important job to do - and I don't want the literary equivalent of an insulted waiter spitting in a customer's soup.

Published on March 02, 2015 00:41

February 27, 2015

Is being an author the most desirable job in Britain?

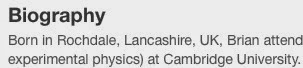

An article in the Independent newspaper was boldly headlined with the news that 'the three most desirable jobs in Britain are author, librarian and academic.' The article begins 'Forget dreams of a glittering career in Premier League football...' Now as an author myself, I feel really thrilled that I've got the country's dream job. But as an author who likes to look at the numbers behind the headlines, I'm a little doubtful about the validity of this story.

An article in the Independent newspaper was boldly headlined with the news that 'the three most desirable jobs in Britain are author, librarian and academic.' The article begins 'Forget dreams of a glittering career in Premier League football...' Now as an author myself, I feel really thrilled that I've got the country's dream job. But as an author who likes to look at the numbers behind the headlines, I'm a little doubtful about the validity of this story. The article was based on a YouGov survey of an impressively large 14,294 British adults, and the chart to the left was the combined outcome.

The article was based on a YouGov survey of an impressively large 14,294 British adults, and the chart to the left was the combined outcome.Well, author is certainly up top. But when you look through that list, there are (at least) two strange additions, which I was very surprised about. No footballers and no pop stars. Isn't that strange?

So it's important to know exactly what YouGov asked - and being a responsible polling organization they give us all the information we need here.

There are a number of fiddly pollster manipulations in the numbers. The sample is weighted, most notably giving less weight to under-forties, though it's not a particularly heavy change. And rather than show people all the options, the were only shown a random sample of 8 jobs, so each particular job was only offered to between 3,643 and 3,797 people - still quite chunky samples.

But there were two particularly interesting points. The data confirm that they neither footballer nor pop star were offered - and as far as I can see, one thing YouGov don't say is how they chose the list. (I have asked YouGov to explain their selection criteria, but they are yet to reply.)

And here's the other thing. The respondents weren't asked 'what would you most like to do?' They were asked 'Generally speaking, please say whether you would or would not like to do each of the following for a living,' for each of the eight options.

So what the survey actually says is this:

We asked people, of the jobs offered (which don't include some of the most common aspirations particularly of young people) which would you like to do and which would you not like to do. 'Author' is the job that the most people said they would like to do.'Note that this doesn't mean that anyone most wanted to be an author from the selections offered. It could have been everyone's fifth choice, say. Just that more people included it in their 'would like to do' list than any other item from the list.

I don't want to knock the poll too vigorously - but there's quite a leap from what it actually measured to how the results have been portrayed in the media.

Published on February 27, 2015 03:12

February 26, 2015

Structural alterations

The British physicist/astronomer, Arthur Eddington was a great science populariser who came up with a lovely comment when writing about quantum mechanics in the late 1920s.

The British physicist/astronomer, Arthur Eddington was a great science populariser who came up with a lovely comment when writing about quantum mechanics in the late 1920s.He wrote that rather than cover the theory as it stood, he really ought to 'nail up over the door of the new quantum theory a notice "Structural alterations in progress - No admittance except on business". And particularly to warn the doorkeeper to keep out prying philosophers.'

I don't think I've seen such a brilliant summary of the way quantum physics went through a transformation from its early implementation, and brought what many physicists would continue to consider far too much agonising over interpretation and philosophy into the field. I think it's fair to say that the notice has come down, but whether those philosophers should have been allowed in is a different matter.

Published on February 26, 2015 00:44

February 24, 2015

Apparently authors can't advertise on Facebook

Like many authors I have a toe in social media - not just this blog (and the associated Google+), but Twitter and Facebook (and LinkedIn) too. I do have some useful social interaction on Facebook, but my Facebook page is dedicated to business - in my case, letting people know about science, writing and my books.

Fair enough, and Facebook positively encourages this, providing opportunities to advertise both your page and specific posts to interested parties. I've never bothered with this - I do a bit of Google advertising in the vain hope that it will push up visibility in the search listings, but Facebook advertising seems like money down the drain. However, the other day I had a post I thought would be benefit from a wider audience so I thought I'd invest the price of a cup of coffee in a couple of days promotion.

Off it duly went to the Facebook censors... only to be rejected fairly smartly because it 'breached guidelines'. Apparently, the image in my 'advert' had too great a percentage with words in it. Now, bear in mind I hadn't designed an ad - all I did was to try to promote a post that pointed to my blogs, and Facebook had automatically picked up the image from the header of the blog. So the 'advert' looked like this:

Now, bear in mind I didn't choose what that image was - Facebook did. And when you think about it, any advertising showing a book's blog header, or a book's cover is liable to have a lot of writing on it. That's what books do.

Get your act together, Facebook! (If you want to see the post about chocolate it was referring to, you can see it here.)

Fair enough, and Facebook positively encourages this, providing opportunities to advertise both your page and specific posts to interested parties. I've never bothered with this - I do a bit of Google advertising in the vain hope that it will push up visibility in the search listings, but Facebook advertising seems like money down the drain. However, the other day I had a post I thought would be benefit from a wider audience so I thought I'd invest the price of a cup of coffee in a couple of days promotion.

Off it duly went to the Facebook censors... only to be rejected fairly smartly because it 'breached guidelines'. Apparently, the image in my 'advert' had too great a percentage with words in it. Now, bear in mind I hadn't designed an ad - all I did was to try to promote a post that pointed to my blogs, and Facebook had automatically picked up the image from the header of the blog. So the 'advert' looked like this:

Now, bear in mind I didn't choose what that image was - Facebook did. And when you think about it, any advertising showing a book's blog header, or a book's cover is liable to have a lot of writing on it. That's what books do.

Get your act together, Facebook! (If you want to see the post about chocolate it was referring to, you can see it here.)

Published on February 24, 2015 01:05

February 21, 2015

You say embargo, I say lumbago

One of the fun things (well, it's sometimes fun) about my job is that I get sent interesting books to review, which I sometimes do for magazines and newspapers, but most of my reviews either appear here on my blog (if it's not a science book) or on my www.popularscience.co.uk website.

When a book arrives from a publisher, it is accompanied by an information sheet/ press release. The bright-eyed and bushy tailed view of these is that they provide useful information for the editor or review writer. (The cynical view is that they provide nice words about the book that some lazy hacks will just reproduce, in classic press release journalism. But I'm not cynical.)

I must confess, I rarely give these more than a quick glance before reading the book. Yes, I do read every book I review, almost always cover to cover, with the exception of books where I decide that my review would be so nasty that I really shouldn't do it - and usually the publisher agrees this is a good move. I don't want the publicists' words to influence my thinking about books - I want to come to it with the same information that a casual purchaser would have.

There are really only two significant things I check - the email address of the publicist, almost inevitably down the bottom, so I can let them know the review has gone live, and the publication date, because I don't want to review a book months before publication, and sometimes I get sent them ridiculously early. (When a book is very early, it is usually a bound proof, rather than a real book, which I don't like. The only possible excuse for this is if the publisher wants me to write a nice couple of lines to go on the back of the book, otherwise they are the devil's spawn.)

When I do glance at the publication date, just occasionally I will see something like this:

From a real book information sheet

From a real book information sheet

(Publisher's name hidden to conceal the guilty)The book comes out on 5 March... but I'm not allowed to write about it until the 2 March. This is an example of the dreaded press embargo. Sometimes these have an obvious point. When, for instance, the shortlist for a book prize is going out to the press, you don't want it published before the date the list is announced. But it's a bit more complicated when it comes to book reviews - and it's not clear what's the best approach.

The idea of an embargo is that readers get all the publicity at about the time the book launches, so it's fresh in people's minds, and I can see that's a good thing. But on the other hand, perhaps it's good to build up the awareness a bit earlier? Perhaps this date doesn't fit well with my publishing schedule?

It was the particular case illustrated above that gave me a bit of a pain in the backside - I wrote the review on Saturday intending to go live with it this weekend... and now I've got to sit on it for a couple of weeks. (The review. Not my backside. Well, not the whole two weeks.)

So... I can see why they do it. It sort of makes sense to get a flurry of activity and awareness around the time the book goes on sale (though if that's really what's wanted, why not embargo it until publication date?). But I honestly don't know if it works in a marketing sense. I'd be interested to hear if anyone has done research on this. And when most books are listed on Amazon months for pre-order months before they are available, I do wonder if the embargo is a concept from a different era.

When a book arrives from a publisher, it is accompanied by an information sheet/ press release. The bright-eyed and bushy tailed view of these is that they provide useful information for the editor or review writer. (The cynical view is that they provide nice words about the book that some lazy hacks will just reproduce, in classic press release journalism. But I'm not cynical.)

I must confess, I rarely give these more than a quick glance before reading the book. Yes, I do read every book I review, almost always cover to cover, with the exception of books where I decide that my review would be so nasty that I really shouldn't do it - and usually the publisher agrees this is a good move. I don't want the publicists' words to influence my thinking about books - I want to come to it with the same information that a casual purchaser would have.

There are really only two significant things I check - the email address of the publicist, almost inevitably down the bottom, so I can let them know the review has gone live, and the publication date, because I don't want to review a book months before publication, and sometimes I get sent them ridiculously early. (When a book is very early, it is usually a bound proof, rather than a real book, which I don't like. The only possible excuse for this is if the publisher wants me to write a nice couple of lines to go on the back of the book, otherwise they are the devil's spawn.)

When I do glance at the publication date, just occasionally I will see something like this:

From a real book information sheet

From a real book information sheet(Publisher's name hidden to conceal the guilty)The book comes out on 5 March... but I'm not allowed to write about it until the 2 March. This is an example of the dreaded press embargo. Sometimes these have an obvious point. When, for instance, the shortlist for a book prize is going out to the press, you don't want it published before the date the list is announced. But it's a bit more complicated when it comes to book reviews - and it's not clear what's the best approach.

The idea of an embargo is that readers get all the publicity at about the time the book launches, so it's fresh in people's minds, and I can see that's a good thing. But on the other hand, perhaps it's good to build up the awareness a bit earlier? Perhaps this date doesn't fit well with my publishing schedule?

It was the particular case illustrated above that gave me a bit of a pain in the backside - I wrote the review on Saturday intending to go live with it this weekend... and now I've got to sit on it for a couple of weeks. (The review. Not my backside. Well, not the whole two weeks.)

So... I can see why they do it. It sort of makes sense to get a flurry of activity and awareness around the time the book goes on sale (though if that's really what's wanted, why not embargo it until publication date?). But I honestly don't know if it works in a marketing sense. I'd be interested to hear if anyone has done research on this. And when most books are listed on Amazon months for pre-order months before they are available, I do wonder if the embargo is a concept from a different era.

Published on February 21, 2015 03:11

February 20, 2015

Two weird quantum concepts

Quantum physics is famous for its strangeness. As the great Richard Feynman once said about the part of quantum theory that deals with the interactions of light and matter particles, quantum electrodynamics:

Dirac's 'sea' emerges from his equation which describes the behaviour of the electron as a quantum particle that is subject to relativistic effects. The English physicist Paul Dirac discovered that his equation, which fits experimental observation beautifully, could not hold without one really weird implication. We are used to electrons occupying different quantised energy levels. This is bread and butter quantum theory. But all those levels are positive. Dirac's equation required there also to be a matching set of negative energy levels.

Dirac's 'sea' emerges from his equation which describes the behaviour of the electron as a quantum particle that is subject to relativistic effects. The English physicist Paul Dirac discovered that his equation, which fits experimental observation beautifully, could not hold without one really weird implication. We are used to electrons occupying different quantised energy levels. This is bread and butter quantum theory. But all those levels are positive. Dirac's equation required there also to be a matching set of negative energy levels.

This caused confusion, doubt and in some cases rage. Such levels had never been observed. And if they were there, you would expect electrons to plunge down into them, emitting radiation as they went. Nothing would be stable. As a mind-boggling patch, Dirac suggested that while these levels existed, they were already full of electrons. So every electron we observe would be supported by an infinite tower of electrons, all combining to fill space with his 'Dirac sea'.

As you might expect, a good number of physicists were not impressed by this concept. But Dirac stuck with it and examined the implications. Sometimes you would expect that an electron in the sea would absorb energy and jump to a higher, positive level - leaving behind a hole in the negative energy sea. Dirac reasoned that such an absence of a negatively charged, negative energy electron would be the same as the presence of a positively charged, positive energy anti-electron. If his sea existed, there should be some anti-electrons out there, which would be able to combine with a conventional electron - as the electron filled the hole - giving off a zap of energy as photons.

It took quite a while, but in the early cloud chambers that were used to study cosmic rays it was discovered that a particle sometimes formed that seemed identical to an electron, except for having a positive charge - the positron, or anti-electron.

Weird though it was, Dirac's concept was able to predict a detectable outcome and moved forward our understanding of physics. As it happens, with time it proved possible to formulate quantum field theory in such a way that the positron was a true particle and the need for the sea was removed, although it remains as an alternative way of thinking about electrons that has proved useful in solid state electronics.

The 'many worlds' hypothesis originated in the late 1950s from the American physicist Hugh Everett. Its aim is to avoid the difficulty we have of the difference between the probabilistic quantum world and the 'real' things we see around us, which seem not to have the same flighty behaviour. Everett didn't like the then dominant 'Copenhagen interpretation' (variants of which are still relatively common) which said that a quantum particle would cease behaving in a weird quantum fashion and 'collapse' to having a particular value when it was 'observed'. This concept gave a lot of physicists problems, especially when it was assumed that this 'observation' had to be by a conscious being, rather than simply an interaction with other particles.

The 'many worlds' hypothesis originated in the late 1950s from the American physicist Hugh Everett. Its aim is to avoid the difficulty we have of the difference between the probabilistic quantum world and the 'real' things we see around us, which seem not to have the same flighty behaviour. Everett didn't like the then dominant 'Copenhagen interpretation' (variants of which are still relatively common) which said that a quantum particle would cease behaving in a weird quantum fashion and 'collapse' to having a particular value when it was 'observed'. This concept gave a lot of physicists problems, especially when it was assumed that this 'observation' had to be by a conscious being, rather than simply an interaction with other particles.

Like the Dirac sea, 'many worlds' patches up a problem with a drastic-sounding solution. In 'many worlds', the system being observed and the observer are considered as a whole. After an event that the Copenhagen interpretation would regard as a collapse, 'many worlds' effectively has a universe that combines both possible states, each with its own version of the observer. So, in effect, the process means that the universe doubles in complexity each time such a quantum event occurs, becoming a massively complex tree of possibilities.

Some physicists like the lack of a need for anything like the odd 'collapse' and the distinction between small scale and large - others find the whole thing baroque in its complexity. What would help is if 'many worlds' could come up with its equivalent of antimatter - a prediction of something that emerges from it but not from other interpretations that can be measured and detected. As yet this is to happen. Whether or not you accept 'many worlds', it is certainly a remarkable example of the kind of thinking needed to get your head around quantum physics.

I’m going to describe to you how Nature is – and if you don’t like it, that’s going to get in the way of your understanding it… The theory of quantum electrodynamics describes Nature as absurd from the point of view of common sense. And it agrees fully with experiment. So I hope you can accept Nature as she is – absurd.It's interesting to compare two of the strangest concepts to be associated with quantum physics - Dirac's negative energy sea and the 'many worlds' interpretation. Each strains our acceptance, but both have had their ardent supporters.

Dirac's 'sea' emerges from his equation which describes the behaviour of the electron as a quantum particle that is subject to relativistic effects. The English physicist Paul Dirac discovered that his equation, which fits experimental observation beautifully, could not hold without one really weird implication. We are used to electrons occupying different quantised energy levels. This is bread and butter quantum theory. But all those levels are positive. Dirac's equation required there also to be a matching set of negative energy levels.

Dirac's 'sea' emerges from his equation which describes the behaviour of the electron as a quantum particle that is subject to relativistic effects. The English physicist Paul Dirac discovered that his equation, which fits experimental observation beautifully, could not hold without one really weird implication. We are used to electrons occupying different quantised energy levels. This is bread and butter quantum theory. But all those levels are positive. Dirac's equation required there also to be a matching set of negative energy levels.This caused confusion, doubt and in some cases rage. Such levels had never been observed. And if they were there, you would expect electrons to plunge down into them, emitting radiation as they went. Nothing would be stable. As a mind-boggling patch, Dirac suggested that while these levels existed, they were already full of electrons. So every electron we observe would be supported by an infinite tower of electrons, all combining to fill space with his 'Dirac sea'.

As you might expect, a good number of physicists were not impressed by this concept. But Dirac stuck with it and examined the implications. Sometimes you would expect that an electron in the sea would absorb energy and jump to a higher, positive level - leaving behind a hole in the negative energy sea. Dirac reasoned that such an absence of a negatively charged, negative energy electron would be the same as the presence of a positively charged, positive energy anti-electron. If his sea existed, there should be some anti-electrons out there, which would be able to combine with a conventional electron - as the electron filled the hole - giving off a zap of energy as photons.

It took quite a while, but in the early cloud chambers that were used to study cosmic rays it was discovered that a particle sometimes formed that seemed identical to an electron, except for having a positive charge - the positron, or anti-electron.

Weird though it was, Dirac's concept was able to predict a detectable outcome and moved forward our understanding of physics. As it happens, with time it proved possible to formulate quantum field theory in such a way that the positron was a true particle and the need for the sea was removed, although it remains as an alternative way of thinking about electrons that has proved useful in solid state electronics.

The 'many worlds' hypothesis originated in the late 1950s from the American physicist Hugh Everett. Its aim is to avoid the difficulty we have of the difference between the probabilistic quantum world and the 'real' things we see around us, which seem not to have the same flighty behaviour. Everett didn't like the then dominant 'Copenhagen interpretation' (variants of which are still relatively common) which said that a quantum particle would cease behaving in a weird quantum fashion and 'collapse' to having a particular value when it was 'observed'. This concept gave a lot of physicists problems, especially when it was assumed that this 'observation' had to be by a conscious being, rather than simply an interaction with other particles.

The 'many worlds' hypothesis originated in the late 1950s from the American physicist Hugh Everett. Its aim is to avoid the difficulty we have of the difference between the probabilistic quantum world and the 'real' things we see around us, which seem not to have the same flighty behaviour. Everett didn't like the then dominant 'Copenhagen interpretation' (variants of which are still relatively common) which said that a quantum particle would cease behaving in a weird quantum fashion and 'collapse' to having a particular value when it was 'observed'. This concept gave a lot of physicists problems, especially when it was assumed that this 'observation' had to be by a conscious being, rather than simply an interaction with other particles.Like the Dirac sea, 'many worlds' patches up a problem with a drastic-sounding solution. In 'many worlds', the system being observed and the observer are considered as a whole. After an event that the Copenhagen interpretation would regard as a collapse, 'many worlds' effectively has a universe that combines both possible states, each with its own version of the observer. So, in effect, the process means that the universe doubles in complexity each time such a quantum event occurs, becoming a massively complex tree of possibilities.

Some physicists like the lack of a need for anything like the odd 'collapse' and the distinction between small scale and large - others find the whole thing baroque in its complexity. What would help is if 'many worlds' could come up with its equivalent of antimatter - a prediction of something that emerges from it but not from other interpretations that can be measured and detected. As yet this is to happen. Whether or not you accept 'many worlds', it is certainly a remarkable example of the kind of thinking needed to get your head around quantum physics.

Published on February 20, 2015 03:54