Brian Clegg's Blog, page 76

March 18, 2015

Where have all the comments gone?

Prompted by a query from Sabine Hossenfelder, I've just changed the comment system on my blog. When it looked like Google+ (which is Google's mostly failed attempt to take on Facebook) was going to take off, it seemed quite sensible to take Google's offer of switching the comment system over to Google+

The good news was that it meant any comments on a blog on Google+, but I hadn't realised until I just looked into it that it also meant that you could only comment if you had a Google+ account.

As a result I've switched the commenting back to Blogger's own. But the downside of this is that some existing comments will disappear. Many apologies if this happens to one of yours. I promise not to change it again!

The good news was that it meant any comments on a blog on Google+, but I hadn't realised until I just looked into it that it also meant that you could only comment if you had a Google+ account.

As a result I've switched the commenting back to Blogger's own. But the downside of this is that some existing comments will disappear. Many apologies if this happens to one of yours. I promise not to change it again!

Published on March 18, 2015 04:48

Why steal a review?

I write a lot of science book reviews, both for magazines and for www.popularscience.co.uk, and I do also put them on Goodreads and Amazon. The other day I got a couple of contacts from Goodreads users, pointing out that someone had copied one of my reviews and published it as their own on their blog. (Thanks to Russa04 and Brendan Schrodinger.)

I couldn't go the blog in question, which had been switched to private, presumably because of complaints, but my informants pointed out that it was still available using the Google cache and low and behold when I went to http://webcache.googleusercontent.com... I found the page shown here:

Which certainly does bear a striking resemblance to my own review (written 6 months earlier):

Which I guess demonstrates that the internet is a dangerous place to resort to plagiarism. But I'm still puzzled. Why bother? Simply to pack out a fairly random website that mostly has music reviews? It seems unnecessarily hard work.

Here's how to do it, Joe Goodglass. Just read a book and write about it. It's not that hard, really.

I couldn't go the blog in question, which had been switched to private, presumably because of complaints, but my informants pointed out that it was still available using the Google cache and low and behold when I went to http://webcache.googleusercontent.com... I found the page shown here:

Which certainly does bear a striking resemblance to my own review (written 6 months earlier):

Which I guess demonstrates that the internet is a dangerous place to resort to plagiarism. But I'm still puzzled. Why bother? Simply to pack out a fairly random website that mostly has music reviews? It seems unnecessarily hard work.

Here's how to do it, Joe Goodglass. Just read a book and write about it. It's not that hard, really.

Published on March 18, 2015 01:38

March 17, 2015

Does my MP think that science is vital?

The

Science is Vital

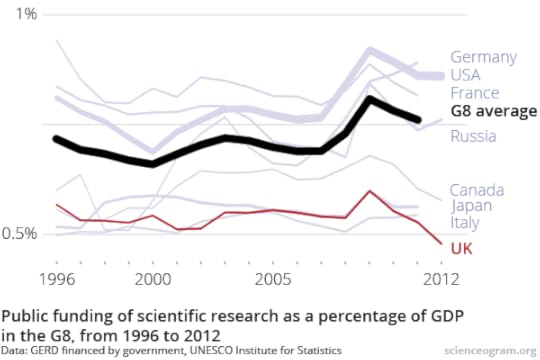

campaign is coming into full swing again, ready for the UK general election. And with good reason. Take a look at that graph.

The

Science is Vital

campaign is coming into full swing again, ready for the UK general election. And with good reason. Take a look at that graph.In the UK we spend a lower percentage of GDP on science than any other G8 country. Our spending has fallen by 15% in real terms since 2010. Germany, the USA and France are all spending around twice as high a percentage of GDP. We simply can't afford to keep ignoring our failing investment in science and it ought to be higher on the political agenda this election.

Why is this important? The reasons come in at all sorts of levels. There's a grounding of 'this is how our universe works - how can it not be important?' There's the enrichment of people's lives in knowing about it - and keeping the interest of children at school, who get turned off it and lose our country important resources.

But also there's a combination of business and survival. It has been estimated that around 35% of GDP is based on quantum physics alone (electronics, lasers, superconductors etc.) - and there's far more when you take in all of science. And everything from medical science to environmental science is central to our survival as a race.

Yet the fact is that very few MPs understand science. The vast majority are arts graduates and make little or no effort to understand what they make spending decisions on. We even have an MP on the science and technology committee who believes we should use astrology more. Unless we make our politicians more aware of the importance of this issue, we risk all our futures. It's that important.

So Science is Vital has encouraged us to write to our local MPs to ask for their support. Mine is Justin Tomlinson. He is a Tory, which means he is not someone I'd naturally support, but he has proved an effective constituency MP in the past. True to form he emailed me back after three days with the following reply. It does seem something of a politician's reply, not saying anything about our miserable spending level, sadly.

Swindon is indeed home to a vast array of science and high technology companies, many of which I have visited during my time as your MP, to see the excellent work that they do.Not a major response at this stage, then - but we can hope that if more of us (more of you!) contact our MPs, the message will start to get across.

I know that both Greg Clark and George Freeman (the current Science and Life Sciences Ministers respectively) and their predecessors get how important science is, particularly to our town. Both Ministers have visited Swindon recently and alongside my South Swindon colleague, Robert Buckland, we have taken them to see the amazing work being done by companies and at research facilities across our town.

I will of course feed your thoughts into the policy-making process and continue to champion the excellent work being done here in Swindon.

What are you waiting for? Hop over to the Science is Vital site for the information you need to contact your MP and get emailing.

Published on March 17, 2015 02:20

March 16, 2015

Lessons from Loki on authors using social media

Authors are often told that we should engage in social media. I do, using Twitter and Facebook (as well as this blog), and it certainly does get me some exposure, but I discovered this weekend what it is to have a tweet really take off.

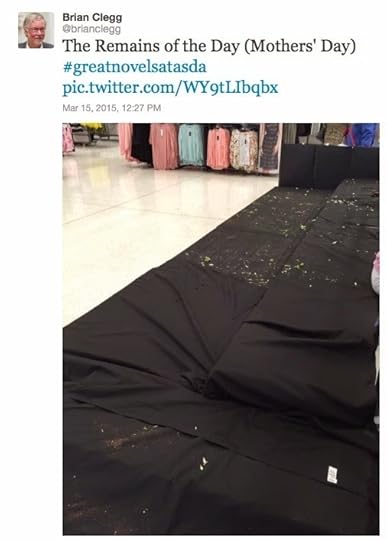

Authors are often told that we should engage in social media. I do, using Twitter and Facebook (as well as this blog), and it certainly does get me some exposure, but I discovered this weekend what it is to have a tweet really take off.The thing that got me pondering how authors should use social media is my tweet shown on the right. With around 1,200 retweets it is in a totally different league to anything I've put on social media before.

I shared the same image with the same words on my Facebook page - it has been liked 26 times and shared once.

I admit this is a very small sample to draw conclusions from, but it does suggest to me that Twitter is the more valuable mechanism for gaining a wider reach out into the world. Of course you have to be lucky with your content - most of my tweets are retweeted between zero and four times - but Facebook users seem far less likely to pass things on and spread the word.

Of course, this hasn't done a lot to get people excited about my books. But that's not really what engaging with people on social media is about. By all means throw in some of your writing-related material - around the same time I tweeted about a misunderstanding over Amazon rankings and about my 'How to write a popular science book' event at the Guardian - and there's no harm mentioning your books as long as you don't turn into one of these people who tweets about their output every few hours, yelling at people to BUY THEM. But your best bet to build up a following you can then interact with on Twitter (and always remember it is a two-way street) is by putting out fairly regular, quirky, potentially entertaining treats.

Of course, one success doesn't make you a Twitter star. A day later, I put out this tweet, which I thought had a certain something:

All it has achieved is 295 views and no retweets (so far).

The final irony about the tube tweet is one of the effects giving it an extra boost was having it picked up by The Metro, the free London newspaper, which featured my tweet in a little article. As a professional writer, part of me feels inclined to moan that my material is being reused free of charge and without permission - but they did give me appropriate credit, and in reality I am rather pleased.

So, simply put, my lessons from Loki are:

When you see something strange or funny, tweet about itIf someone comments on your tweet reply (or like it if that's more appropriate) - Twitter is about a conversation, not just broadcasting your words of wisdomThere's a huge amount of luck - you can't predict the timing, wording, image that will have this effectBy all means tweet about your books as well, but don't let it dominate

Published on March 16, 2015 02:26

March 13, 2015

Hit by a Newton bomb

Excuse the blur...I’m getting in a real mental twist over Isaac Newton’s birth and death dates. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Scientists, fuzzily illustrated here, they were 1642-1727, but I think that this is wrong. You can either say they were 1642-1726 or 1643-1727 but not plump for half and half.

Excuse the blur...I’m getting in a real mental twist over Isaac Newton’s birth and death dates. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Scientists, fuzzily illustrated here, they were 1642-1727, but I think that this is wrong. You can either say they were 1642-1726 or 1643-1727 but not plump for half and half.The trouble is that the change of calendar we have had since Newton's time produced two effects. One is that the date jumps forwards (10 days at his birth, 11 by his death), and the second is that the date that the year changed moves from March 25th (don’t ask) to January 1st.

In the dates that would have been used by Newton himself, he was born on Christmas Day 1642 and died on 20 March 1726. (If he had died instead on 25 March, it would have been 1727.) Alternatively, if we decide to impose our present dating system on the past, he was born on 4 January 1643 and died on 31 March 1727. This is upsetting for those who like to make the handing-on-the-baton observation that Newton was born in the same year that Galileo died.

So which dates should we use? In one case, there is no argument. When talking about the anniversary, we have to use modern dating. So if you said on Christmas day 2042 that Newton was born 400 years ago, you would be plain wrong. But for the rest it's a more difficult decision. It somehow feels right to make use of the dates of the time - but then you have a problem with using BC dates. After all, when Archimedes had his twentieth birthday in 267 BC (did ancient Greeks celebrate birthdays?), he was hardly likely to call it 267 BC or to ponder on the fact that Christ was going to be inaccurately dated as being born 267 years in the future.

The other problem with using contemporary dating is that, for instance, when Newton was alive, some of his European friends were already using the Gregorian calendar. So how do you date an event where Newton interacts with someone in France, say? It's a worry.

I suspect, then, that it's probably best to stick to new style dating. So it's 1643-1727. Okay?

Published on March 13, 2015 02:45

March 12, 2015

What is design for? The new Apple Macbook, hobs and toilet doors

Of all the companies involved in the IT and communications world, Apple arguably has the most style and elegant design. We all know that design is brilliant on a thing you just look at, but when you also have to use it, usability comes in too - and there is frequently a tension between the two.

Of all the companies involved in the IT and communications world, Apple arguably has the most style and elegant design. We all know that design is brilliant on a thing you just look at, but when you also have to use it, usability comes in too - and there is frequently a tension between the two.Many years ago, I did quite a lot of work on user interface design, and that's all about the balance, making something that looks good, but is also effortlessly usable. Generally speaking, Apple's UI designers get this, and in part maintain it by keeping more of a grip on the user interface than do rivals. However, on Apple's hardware side, the design/usability balance has sometimes strayed too far towards looks above function.

This happens all the time in everyday items. I've mentioned before the toilet doors at the British Airways Waterside HQ, which had pull handles on both sides, even though you had to push them when going in. I used to delight in watching person after person approach the door, pull it (because that's what you automatically do when you see a pull handle), fail, hesitate, then push the door. The designer let the visual elegance of symmetry overcome the practical value of a push plate.

Another great example I've mentioned before is the hob - the bit of the cooker with rings that you put pans on. Most of these have four rings, arranged in a rectangular shape. But because it looks better, designers almost always put the controls for these rings in a straight line. So there is no way of telling which control is for which ring without looking at the labels. If they just put the controls in the same shape as the rings it would be immediately apparent without any labelling.

So we come to Apple's new Macbook, coming out next month. It looks gorgeous. Super slim with stunning graphics. It may well be one of my favourite laptops ever. And the designers have really thought about how nasty the side of a typical laptop looks with all those different shaped ports and have come up with a cunning design of a single type of port, USB-C (see pic above) that can act as power in, USB, display adaptor, HDMI - whatever you need. Because the laptop is so slim you could only get one of these per side, but because they're so flexible, you'd be happy with the limit of just having two of them. But it only has one.

Just think about that. A single port for everything. Design bliss possibly (though for symmetry, there really ought to be one each side). But practical? Hardly. Okay, battery life is good, but who would willingly do a whole day's presentation from a laptop that can't be connected to the mains, because the only socket is being used to connect it to the projector? As it happens, Apple has that one covered. You have always had to have a special adaptor to connect a Mac's proprietary video port to the VGA or HDMI used by video projectors. So the new adaptor not only has a video out socket, but also a connector for the mains unit (and a USB socket). That's okay, although arguably this should come with the laptop, rather than being a £65 extra.

However, that's not the only problem. Far more people use USB sockets at the same time as the power than use projectors. They might need to swap information on and off a memory stick. They might be synchronising or charging a phone or iPod. They might want to pop on a USB mouse. Well, tough. If you want to do this, you will have to disconnect your mains supply, unless you spend £65 on one of those adaptors. If your laptop is low on charge - doubly tough. You will just have to wait to get those extremely urgent documents off that secure memory stick, because you will run out of battery if you disconnect the mains.

This can't be good. Just putting one socket either side - or providing a USB/mains adaptor with the laptop - would have made all the difference. But design has triumphed. In fact it has even robbed us of one of Apple's unique features. Anyone who has sat in a living room with four people all using laptops on mains cables will know the hazard they form. You either trip over a cable, or send a laptop flying off the sofa to crash to the floor as your foot gets wrapped in the wire. So for many years, Apple has a used a lovely 'MagSafe' connector that doesn't plug in, but is attached magnetically. Get your foot caught in this cable and it detaches safely. But the new USB-C connector isn't magnetic. Lose-lose it seems.

When I get my hands on one of these it may still be one of my favourite laptops ever, and in the end I suspect I will overlook this flaw. But that doesn't stop it being a sad example of design over usability.

Published on March 12, 2015 02:09

March 11, 2015

The wonderful world of Ladybird art, science and technology

If you are of a certain age in the UK, you will have read Ladybird books as a child. The brand, owned now by Penguin/Random House, has been resurgent for some time, and there are plenty of the small format, large print books available.

If you are of a certain age in the UK, you will have read Ladybird books as a child. The brand, owned now by Penguin/Random House, has been resurgent for some time, and there are plenty of the small format, large print books available.I was inspired to write this post by the science and technology bit I'll come onto in a moment, but I must start with the art part, which combines the best subversive pastiche I've ever seen with some real David and Goliath action.

A couple of years ago, artist Miriam Elia produced a spoof Ladybird book called We Go to the Gallery. It has exactly the same format as a Ladybird reading scheme book, and used images from original book(s), but here the format is used to provide a wonderful and subversive take on modern art. Here's an example of the text for the page that has the same image as the cover of the book:

There is nothing in the room.

Peter is confused.

Jane is confused.

Mummy is happy.

'There is nothing in the room because God is dead,' says Mummy.

'Oh dear,' says Peter.

The book is absolutely brilliant and was immediately popular. Orders started to flood in and a first run was printed, but then Penguin muscled in with demands that the print run be pulped because of breach of copyright of the images Elia had used. The legal battle has rumbled on for some time, with Penguin consistently unable to produce any evidence that they had copyright in the images. Since changes to the law making spoofs and satires less open to legal change, and a change in Elia's design to make it a Dungbeetle Book instead, a new version is sale (you can only buy the books directly from Elia's website - well worth a look.

The science and technology side was brought to my attention by the excellent actor

We can laugh at the way that their book on 'The Rocket' portrayed the future of space travel, or the ungainly 'mini computer control unit' in 'The Computer'. But what's really sad is that they show examples where children are investigating what's in a battery by pulling it to pieces, or starting a fire (to cook sausages) with a magnifying glass and the BBC writer comments that this would never be allowed today because of health and safety.

I think it's fair to say that most of the scientists I know of my kind of age did plenty of hairy experiments in their youth (in my case, mostly in chemistry, and often featuring bangs) and I genuinely believe that we ought to recognize the need for a little more risk taking in the development of our scientists of the future. I took batteries apart too - quite possibly inspired by a Ladybird book. And I'm glad I did.

To finish off, here's a little Channel 4 News video from March 2014 with more on the spoof Ladybird art book.

Published on March 11, 2015 01:58

March 10, 2015

A rank error

There's are two distinct shifts of focus when you become an author. First it's all about getting the book (or proposal if it's non-fiction) in a perfect state to send off to agents/publishers. Then it's all about getting someone to publish it. And once it's out there, it's about whether or not, and how much, it sells.

Now, you will get a few authors who genuinely say 'I don't care about sales. It's all about the art/achievement/fulfilling a lifelong goal.' But for most of us sales matter - and the more, the merrier. It can come as quite a surprise to a new author that sales are really quite opaque. Mostly publishers will only update you on sales in their twice-a-year (or even annual) royalty statement. Which is sent out typically four months after the end of the previous sales period. That's a long time to wait to find out how your baby is doing.

Clearly the publishers have access to much better information, but rarely do they give access to authors. The only exception I know of is Penguin Random House, which has an 'author portal' website which gives figures for both 'shipped' and 'sold' on a weekly basis, up to last week. (The difference between the two figures is a scary one, bearing in mind the book trade has the archaic system that stores take their books on a sale or return basis.) If other publishers have similar systems for their authors, please let me know.

Otherwise authors really only have one place to turn. Amazon. The behemoth of books has a magic number on the page of every book that has sold at least one copy called its 'bestsellers rank'. In one sense this is quite simple. A big number (potentially in the millions) means it's not selling much at all. Numbers get smaller when more are selling. So, for instance, if I nip to the page of a book I liked very much when I reviewed it, Lee Smolin's Time Reborn , which has been around since 2013, I see this:

The book's 'Bestsellers Rank' (previously called sales rank) is perfectly respectable 16,092. (You will also note that it is number 48 in Astronomy, which is odd (if typical) as it's not an astronomy book, but that's more use for boasting than monitoring sales.) And what an author can do is keep an eye on that bestsellers rank and see how it goes up and down to get a feel for sales. There's even an impressive free (if slightly fiddly) website called NovelRank, that monitors the number for you.

So, I suspect a number of authors felt the bottom had dropped out of their world when a Huff Post blog post announced that 'Your Amazon ranking has nothing to do with sales.' This post by Brooke Warner claimed that 'all your ranking means is that people are looking at your page.' This would be very depressing if true. But is it true? Warner gives no source for her assertion, although in answers to comments she refers to 'my Amazon source', so presumably has a contact who works there - but that doesn't mean she is right.

While no one can say definitively what goes on in Amazon's no doubt byzantine algorithm (or 'logarithm' as Ms Warner engagingly called it until she was corrected) there is strong evidence that it is primarily sales based. First, Amazon actually says it is. They say here, referring to the sub-categories, but then bringing in the main rank: 'As with the main Amazon Best Sellers list, these category rankings are based on Amazon.com sales and are updated hourly.' That's a pretty straight answer. And NovelRank's creator, Mario Lurig, who told me that Warner was 'wrong. Flat out.' has a useful page pulling apart various myths about the ranking - his conclusions may be based on small samples sometimes, but everything he says bears out the experience of regular sales watchers.

It's quite interesting to read the comments of Warner's post, as she becomes increasingly defensive, falling back on the statement that what she really meant was that the rank shows how well a book is selling 'in relation' to other titles. (And says she'll get Huff Post to correct her main text, which may have happened by the time you read this.) However, sadly, this just shows once more Warner's limited grasp of anything vaguely mathematical. Of course a ranking is relative to other titles - that's why it's a ranking, rather than an absolute sales figure. But it still should go up when you make sales, and then decay until your next sale.

The only proviso to this, which Lurig makes clear on his site, is that if you are lucky enough to get a ranking in 3 figures or lower, it won't go up for each sale, because at that kind of level, books are selling fast enough to have more than one per hour, and selling 20 in that hour, say, won't be much different in rank change from selling 21.

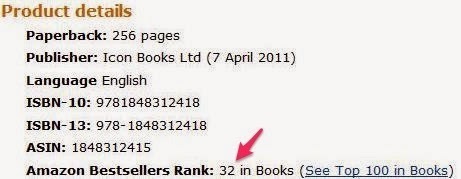

So, conclusion? Amazon Bestsellers rank is still the best guide authors have to sales, and when it goes up, you can be pretty sure you have made a sale. Here's my best ranking outside of Kindle (where there are fewer titles) to date. We can always hope for smaller...

Now, you will get a few authors who genuinely say 'I don't care about sales. It's all about the art/achievement/fulfilling a lifelong goal.' But for most of us sales matter - and the more, the merrier. It can come as quite a surprise to a new author that sales are really quite opaque. Mostly publishers will only update you on sales in their twice-a-year (or even annual) royalty statement. Which is sent out typically four months after the end of the previous sales period. That's a long time to wait to find out how your baby is doing.

Clearly the publishers have access to much better information, but rarely do they give access to authors. The only exception I know of is Penguin Random House, which has an 'author portal' website which gives figures for both 'shipped' and 'sold' on a weekly basis, up to last week. (The difference between the two figures is a scary one, bearing in mind the book trade has the archaic system that stores take their books on a sale or return basis.) If other publishers have similar systems for their authors, please let me know.

Otherwise authors really only have one place to turn. Amazon. The behemoth of books has a magic number on the page of every book that has sold at least one copy called its 'bestsellers rank'. In one sense this is quite simple. A big number (potentially in the millions) means it's not selling much at all. Numbers get smaller when more are selling. So, for instance, if I nip to the page of a book I liked very much when I reviewed it, Lee Smolin's Time Reborn , which has been around since 2013, I see this:

The book's 'Bestsellers Rank' (previously called sales rank) is perfectly respectable 16,092. (You will also note that it is number 48 in Astronomy, which is odd (if typical) as it's not an astronomy book, but that's more use for boasting than monitoring sales.) And what an author can do is keep an eye on that bestsellers rank and see how it goes up and down to get a feel for sales. There's even an impressive free (if slightly fiddly) website called NovelRank, that monitors the number for you.

So, I suspect a number of authors felt the bottom had dropped out of their world when a Huff Post blog post announced that 'Your Amazon ranking has nothing to do with sales.' This post by Brooke Warner claimed that 'all your ranking means is that people are looking at your page.' This would be very depressing if true. But is it true? Warner gives no source for her assertion, although in answers to comments she refers to 'my Amazon source', so presumably has a contact who works there - but that doesn't mean she is right.

While no one can say definitively what goes on in Amazon's no doubt byzantine algorithm (or 'logarithm' as Ms Warner engagingly called it until she was corrected) there is strong evidence that it is primarily sales based. First, Amazon actually says it is. They say here, referring to the sub-categories, but then bringing in the main rank: 'As with the main Amazon Best Sellers list, these category rankings are based on Amazon.com sales and are updated hourly.' That's a pretty straight answer. And NovelRank's creator, Mario Lurig, who told me that Warner was 'wrong. Flat out.' has a useful page pulling apart various myths about the ranking - his conclusions may be based on small samples sometimes, but everything he says bears out the experience of regular sales watchers.

It's quite interesting to read the comments of Warner's post, as she becomes increasingly defensive, falling back on the statement that what she really meant was that the rank shows how well a book is selling 'in relation' to other titles. (And says she'll get Huff Post to correct her main text, which may have happened by the time you read this.) However, sadly, this just shows once more Warner's limited grasp of anything vaguely mathematical. Of course a ranking is relative to other titles - that's why it's a ranking, rather than an absolute sales figure. But it still should go up when you make sales, and then decay until your next sale.

The only proviso to this, which Lurig makes clear on his site, is that if you are lucky enough to get a ranking in 3 figures or lower, it won't go up for each sale, because at that kind of level, books are selling fast enough to have more than one per hour, and selling 20 in that hour, say, won't be much different in rank change from selling 21.

So, conclusion? Amazon Bestsellers rank is still the best guide authors have to sales, and when it goes up, you can be pretty sure you have made a sale. Here's my best ranking outside of Kindle (where there are fewer titles) to date. We can always hope for smaller...

Published on March 10, 2015 02:09

March 9, 2015

Scientist, heal thyself

An interesting blog post was brought to my attention in something written by Sabine Hossenfelder, a physics professor who has a real passion for the better communication of science.

An interesting blog post was brought to my attention in something written by Sabine Hossenfelder, a physics professor who has a real passion for the better communication of science. She picked out a passage in the blog, commenting 'spot on':

Sciencey headlines are pre-packaged cultural tokens that can be shared and reshared without any investment in analysis or critical thought — as if they were sports scores or fashion photos or poetry quotes — to reinforce one’s aesthetic self-identification as a “science lover.” One’s actual interest doesn’t have to extend beyond the headline itself.I must admit, I find that paragraph hard to understand, and while it may sound correct in isolation (if it means what I think it means), it doesn't work in the context of the rest of the text. The central thesis of the post is that scientists aren't making the outrageous claims. It's partly the fault of science journalists ('overblown science headlines are still a major aspect of the problem') and partly the fault of the ignorant unwashed general public ('many of your friends and relatives — and most likely, even you — are now implicated in this onslaught of misinformation').

However, in my experience, these contortions of the true picture of science largely originate with scientists and with university press offices - not the science journalism community or the public at large. I'm not saying science journalism isn't rife with misinformation that has come from the journalist (often not a science journalist but a health or lifestyle correspondent or similar) - but I'd suggest the biggest sources are back at the universities.

Let me give you two examples.

If I am writing about, say, the big bang, I always make sure I include the proviso that what I am covering is the current best-accepted theory given the data we have right now, but that the picture may change in the future. I have lost count of the number of scientists who write something like 'the universe began around 13.7 billion years ago...' and go onto describe the hot big bang with inflation model as if it were absolute fact.

And then there's the matter of light sabers. (I know it should be 'light sabres', but that's the way they spell it.) Here are some newspaper headlines from 2013: 'Star Wars lightsabers finally invented,' 'Scientists Finally Invent Real, Working Lightsabers,' and 'MIT, Harvard scientists accidentally create real-life lightsaber' were among the dramatic headlines. (I love that use of 'Finally' as if it is about time that those lazy scientists managed to get around to something so trivial.) Silly journalists. Now all the common unwashed people will think that light sabers really exist.

Is this what had happened in the lab? Nope. By using a Bose-Einstein condensate, the scientists had been able to create what they called 'light molecules' - pairs of photons that were temporarily linked together. Interesting, and possibly useful in photonics, but not a light saber by any stretch of the imagination. So how did those wacky science journalists come up with the imaginary light saber image? Did they just make it up? No. One of the scientists involved, Professor Mikhail Lukin of Harvard said: “It’s not an inapt analogy to compare this to light sabers.”

Perhaps, then, the answer is that scientists who like the media spotlight should think twice before coming out with such a remark. And then not do it. But to blame this kind of thing on science journalism (why should the journalist know more than the professor?) or the unwashed public (why shouldn't they find a headline like that worth repeating?) is simply wrong.

Published on March 09, 2015 02:01

March 6, 2015

Happy Birthday, Phil!

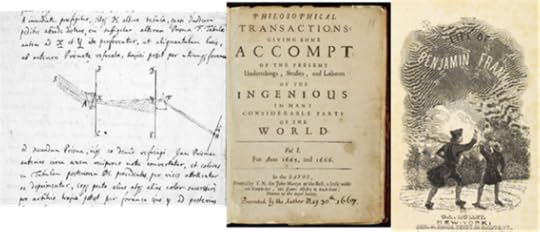

Yes, it's birthday time today for old Phil Trans, or more properly Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, the world's oldest continuously published scientific journal which is 350 years old today.

Back on 6 March 1665 (centre image), the first copies of this remarkable document appeared in London. Since then it has carried a whole range of mid boggling papers, including everything from Newton's breakthrough paper on light and colour in 1672 (left image), Benjamin Franklin's account of flying a kite in a storm (not performed personally it now seems) in 1752, Eddington's (rather dodgy) 'proof' of the general theory of relativity from eclipse observations in 1919, published in 1920, through to the present day.

What sadly it no longer includes are the more wacky topics that turned up in the past, from an account of a 'very odd monstrous calf' (by Robert Boyle in the first volume) and 'of a way of killing ratle-snakes (sic)' to an analysis of the young Mozart that somehow managed to deduce he really was a musical genius.

Those nice people at the Royal Society are celebrating by making all RS journals content free to access to the end of March (though to be fair, they ought to always be free to access). There are also special commemorative issues, films and more - take a look at the 'Publishing 350' site.

You can read more about the history of Philosophical Transactions, and download a 26 page ebook on it here.

If you want to read the very first issue, you can also do this, as all the historical editions of Transactions up to 1943 are available freely online here. Scroll down to the bottom to find volume 1.

Altogether now: Happy Birthday to you, Happy Birthday to you! Happy Birthday, dear Phil, Happy Birthday to you!

Back on 6 March 1665 (centre image), the first copies of this remarkable document appeared in London. Since then it has carried a whole range of mid boggling papers, including everything from Newton's breakthrough paper on light and colour in 1672 (left image), Benjamin Franklin's account of flying a kite in a storm (not performed personally it now seems) in 1752, Eddington's (rather dodgy) 'proof' of the general theory of relativity from eclipse observations in 1919, published in 1920, through to the present day.

What sadly it no longer includes are the more wacky topics that turned up in the past, from an account of a 'very odd monstrous calf' (by Robert Boyle in the first volume) and 'of a way of killing ratle-snakes (sic)' to an analysis of the young Mozart that somehow managed to deduce he really was a musical genius.

Those nice people at the Royal Society are celebrating by making all RS journals content free to access to the end of March (though to be fair, they ought to always be free to access). There are also special commemorative issues, films and more - take a look at the 'Publishing 350' site.

You can read more about the history of Philosophical Transactions, and download a 26 page ebook on it here.

If you want to read the very first issue, you can also do this, as all the historical editions of Transactions up to 1943 are available freely online here. Scroll down to the bottom to find volume 1.

Altogether now: Happy Birthday to you, Happy Birthday to you! Happy Birthday, dear Phil, Happy Birthday to you!

Published on March 06, 2015 08:04