Sarah Sundin's Blog, page 379

July 15, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 15, 1944

70 Years Ago—July 15, 1944: Finnish forces stop the Soviet advance in the Karelian Isthmus. US Navy PB4Y Liberators bomb Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima, and Haha Jima.

70 Years Ago—July 15, 1944: Finnish forces stop the Soviet advance in the Karelian Isthmus. US Navy PB4Y Liberators bomb Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima, and Haha Jima.

July 14, 2014

Port Chicago – The Explosion

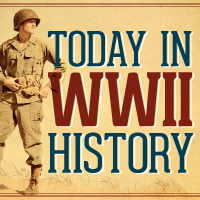

Damage at US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago from 17 July 1944 explosion. (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

In the worst Home Front disaster of World War II, an explosion at the Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California on July 17, 1944 killed 320 men, of whom 202 were black. The tragedy was followed by a work stoppage and a controversial mutiny trial. This sent ripples of change through the segregated armed forces.

I included these events in my third novel, Blue Skies Tomorrow. Last week I discussed the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, today I’ll cover the explosion, and over the next few weeks we’ll look at the work stoppage, trial, and aftermath.

One Summer Night

The evening of Monday July 17 was cool, clear, and moonless. Down by Suisun Bay, where the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers merge, floodlights illuminated the docks at the U.S. Naval Magazine at Port Chicago, California.

The U.S. Navy in the Pacific depended on the ammunition loaded at Port Chicago, so men worked around the clock. For the night shift, two divisions of about one hundred black men each were hard at work loading two cargo ships from sixteen boxcars on the rails leading to the dock. Nine white officers and twenty-nine armed white Marine guards were also present, along with the crews of both ships and a Coast Guard fire barge moored nearby.

The SS E.A. Bryan, a Liberty ship, had already been loaded with 4600 tons of cargo by 10 pm, including fuzed (live) 650-lb incendiary bombs, depth bombs, 1000-lb bombs, 40-mm shells, and frag. cluster bombs. The SS Quinault Victory (also spelled Quinalt), a brand-new Victory ship, had docked at 6 pm to be loaded for her maiden voyage starting at midnight. About 429 tons of explosives were on the docks or in the boxcars at 10 pm.

Damage on docks at US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago from 17 July 1944 explosion (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

The Explosion

At 10:18 pm, two massive explosions occurred, seven seconds apart, equivalent to five kilotons of TNT, about the same magnitude as the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The first explosion appears to have happened on the dock area, and the second explosion was most likely the E.A. Bryan exploding as a whole.

A flash of bright orange, a sound like giant doors slamming, and a column of fire, smoke, and debris rose to over 12,000 feet. Exploding shells within the column of smoke produced effects like fireworks. An Army Air Force plane at 9000 feet reported seeing debris above its altitude.

The Damage

On the ships and docks, all 320 men present were killed instantly, 202 of whom were black. (News sources at the time reported the figure of 322 deaths; therefore, I used that figure in Blue Skies Tomorrow.) The E.A. Bryan completely disintegrated, and the Quinault Victory spun 180 degrees and snapped in two. The dock, locomotive, and boxcars disappeared.

Out on the river, two nearby boats were swamped by a thirty-foot wave, killing one, and the nearby Roe Island Lighthouse was seriously damaged.

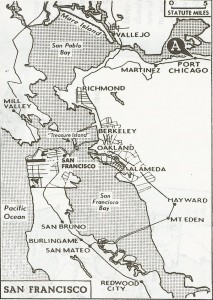

On the base, every single building was damaged. The explosion knocked men off their feet and out of windows over a mile and a half away. In the town of Port Chicago, almost every home was damaged, but no one was killed. The explosion was felt within a 40-mile radius, as far away as San Francisco. Windows were blown out and plaster shaken down in Pittsburg, Antioch, Martinez, Benicia, and Vallejo.

About 390 people were injured, military and civilians. The most common injuries resulted from flying glass, including many who were blinded. The first explosion brought people to the windows to investigate, then the second explosion shattered the windows.

Some of those close to the explosion thought the Japanese were bombing. Those further away judged the rumbling and shaking as an earthquake.

Damage to rail cars at US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago from 17 July 1944 explosion (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

Rescue Efforts

On the base, the uninjured quickly and calmly rallied for search and rescue and first aid. Local military bases and civilian fire departments sprang to action. The first ambulances arrived within thirty minutes and transported the wounded to local hospitals. Local Red Cross, USO, and Salvation Army groups provided aid on the base and in the local communities.

Cause of the Explosion

Since every eyewitness to the explosion was killed, the exact cause of the explosion will never be determined. Poor training and leadership emphasized speed over safety, and several of the booms had been reported to have faulty parts. Since fuzed incendiary bombs were being loaded, rough handling or an accident could easily have led to a dockside explosion, which then spread to the heavily loaded E.A. Bryan.

Sources:

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny. Berkeley CA: Heyday Books, 2006.

Port Chicago Naval Magazine Explosion on 17 July 1944: Court of Inquiry: Finding of Facts, Opinion and Recommendations. Washington DC: Department of the Navy, 30 October 1944. On Naval Historical Center website. Accessed 9 October 2011. http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq80-4a.htm

Antioch Ledger, various articles, July 1944. Accessed on microfiche, Antioch Public Library, Antioch CA.

Today in World War II History—July 14, 1944

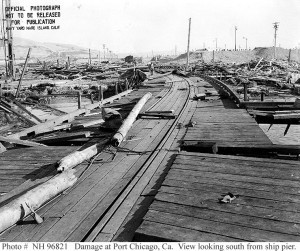

B-17 of US 94th Bomb Group drops supplies to French Resistance in Vercors region, 14 July 1944. (USAAF photo)

70 Years Ago—July 14, 1944: On Bastille Day, US Eighth Air Force B-17s make supply drop to resistance forces in southern France. Glenn Miller’s first performance at English airfield: at Thurleigh for 306th Bomb Group in a hangar with 3500 in attendance. In California, Shasta Dam opens.

July 13, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 13, 1944

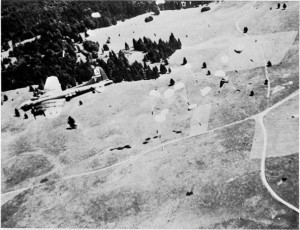

Native litter bearers evacuate an American casualty across the Driniumor River in New Guinea, 1944. (US Center of Military History)

70 Years Ago—July 13, 1944: Mayo clinic announces that cigarettes may harm wounded men due to vasoconstriction. On New Guinea near Aitape, US pushes to Driniumor River, dividing Japanese 18th Army.

July 12, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 12, 1944

Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. in Normandy, July 1944 (US National Archives)

70 Years Ago—July 12, 1944: Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr., son of the former president, dies of a heart attack in Normandy. Nazis close Theresienstadt concentration camp after murdering last 4000 Jews.

July 11, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 11, 1944

Captured German Fourth Army being paraded through Moscow, 17 July 1944 (Russian Archives)

70 Years Ago—July 11, 1944: Soviets capture entire German Fourth Army in Minsk area; 37,000 POWs.

July 10, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 10, 1944

Raoul Wallenberg, June 1944 (public domain)

70 Years Ago—July 10, 1944: US Fifth Fleet under Admiral Nimitz begins carrier strikes against Tokyo. Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg reports to Swedish embassy in Budapest, Hungary as a secretary; he will issue protective passports and save the lives of thousands of Jews.

July 9, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 9, 1944

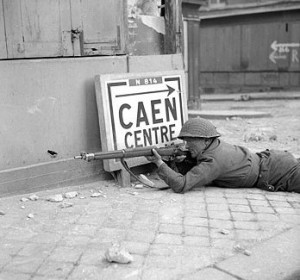

British soldier in Caen, France, 9 July 1944 (Imperial War Museum)

70 Years Ago—July 9, 1944: US secures Saipan in Marianas. British Second Army takes crucial city of Caen in Normandy. In Hungary, Miklós Horthy temporarily stops deportation of Jews.

July 8, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 8, 1944

Barrage balloons over Buckingham Palace in London during WWII (RAF photo)

70 Years Ago—July 8, 1944: In Normandy, British & Canadians launch assault on Caen and enter city. British launch 1750 barrage balloons south of London to combat German V-1 buzz bombs. US Army commands all PXs, theaters, and transportation open to all races.

July 7, 2014

The Port Chicago Disaster – Introduction

Damage to building A-14 at the US Naval Magazine , Port Chicago, 17 July 1944 (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

In the worst Home Front disaster of World War II, an explosion at the Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California on July 17, 1944 killed 320 men, of whom 202 were black. The tragedy was followed by a work stoppage and a controversial mutiny trial. This sent ripples of change through the segregated armed forces.

Despite its significance, few people have heard about Port Chicago. I included these events in my third novel, Blue Skies Tomorrow, and over the next few weeks, I’ll discuss the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, the explosion, work stoppage, trial, and aftermath.

Segregation of the US Armed Forces in World War II

All branches of the U.S. armed forces were segregated during World War II. Jim Crow rules were followed, supposedly so as not to offend the sensibilities of white Southerners. Blacks served in separa te units and used separate barracks, mess halls, recreational facilities, and transportation.

te units and used separate barracks, mess halls, recreational facilities, and transportation.

In 1940, the Army had few commissioned black officers, and the Navy had none. Due to paternalistic attitudes at the time, blacks usually served under white officers, often from the South. The rationale was that Southerners had a “special understanding” of how to work with blacks.

In the Army, the bulk of black men served in Quartermasters or Engineers, and rarely in combat units. In 1940, all the blacks in the Navy served in the Steward’s Branch (mess).

These conditions were difficult to bear, especially for men from northern or western states, who had never lived under Jim Crow laws.

Slow Gains During the War

Slow Gains During the WarAfter the United States instituted the peacetime draft on September 16, 1940, leaders from the NAACP and other black organizations met with President Roosevelt on September 27 to air their grievances about segregation. Roosevelt responded on October 9 by allowing blacks to become commissioned officers—over black units only—but he retained segregation. He followed this action by promoting Benjamin O. Davis Sr. to brigadier general, the Army’s first black general. (Davis’s son, Benjamin O. Davis Jr. would later lead the Tuskegee Airmen).

One of the nation’s first war heroes was a black man. On the morning of December 7, 1941, Mess Attendant Second Class Doris “Dorie” Miller (pictured in the poster) was collecting laundry on board the USS West Virginia in Pearl Harbor. The Japanese attacked. The alarm for general quarters sounded, and Miller reported to his battle station, an antiaircraft battery amidships. It had already been destroyed. A heavyweight boxer, Miller carried wounded sailors to safety, aided the mortally wounded captain, and manned a .50 caliber machine gun—a weapon he’d never been trained to use—and was credited with downing a Japanese fighter plane. For his bravery, he received the Navy Cross on May 27, 1942. Sadly, he perished when the USS Liscome Bay was sunk by a Japanese submarine on November 24, 1943.

On February 7, 1942, the Pittsburgh Courier, the nation’s foremost black newspaper, announced the “Double V Campaign” to fight for victory and freedom at home as well as abroad.

As of June 1, 1942, blacks were allowed to enlist in the Navy for general service, not just the mess. However, they were restricted to work in Construction Battalions (the Seabees), in ammunition loading, and to stateside duties. On July 12, 1943, the Navy allowed blacks to be rated and promoted on the same basis as whites, but not until March 17, 1944 did the first twelve black officers enter service in the Navy.

These minor gains did little to appease. In the summer of 1943, race riots sprang up around the nation—from Los Angeles to Harlem, from Detroit to Mobile.

Naval Magazine, Port Chicago

Naval Magazine, Port ChicagoThe Naval Ammunitions Depot at Mare Island, Vallejo, California provided a large quantity of supplies for the Pacific Fleet. A subcommand of Mare Island was established at nearby Port Chicago on January 28, 1942. Construction soon began, and the first ship moored at Port Chicago on December 8, 1942.

Port Chicago lies by the deep water of Suisun Bay, where the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers merge before entering San Francisco Bay. The area was sparsely populated at the time, and the little town of Port Chicago (population 1000), was served by two transcontinental railroads, the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe.

A single wooden pier allowed for one cargo ship to be loaded at a time. This was widened to twenty feet as of May 10, 1944, which allowed two ships to be loaded simultaneously.

Conditions at Port Chicago

At Port Chicago, eight divisions of 100-125 men worked around the clock. All the men working as stevedores (ammunition loading) were black, as were the petty officers. All commissioned officers and Marine guards were white.

The enlisted men arrived straight from the basic training centers, without any specific training in handling munitions. In addition, none of the officers had munitions handling experience either. Only two lectures on safety were given before the explosion.

To increase speed of loading, the officers instituted competitions between divisions, offering free movies to the winning group. There were also reports of betting among the officers. These conditions did not foster safety.

Morale was low at Port Chicago. The discrimination and segregation in the Navy, coupled with the lack of promotions or the chance to earn specialized ratings led to an apathetic attitude for many of the men. In addition, they earned lower pay than civilian stevedores. Not until June 1944 did the men have recreational facilities on the base, and no military transport was provided to Oakland or San Francisco for the men’s leaves.

Not all the men complained. Some were grateful for the opportunity to prove their worth through service. And one common complaint only proved the men’s patriotism—they wanted the right to go to combat and fight for their country.

Sources:

MacGregor, Morris J. Jr. Integration of the Armed Forces 1940-1965. Washington DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1985. On U.S. Army Center of Military History website. Accessed 2 October 2011. http://www.history.army.mil/books/integration/IAF-FM.htm

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny. Berkeley CA: Heyday Books, 2006.

War Time History of U.S. Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, California. Washington DC: US Navy Bureau of Ordnance, 5 December 1945. On Naval Historical Center website. Accessed 2 October 2011. http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq80-3d.htm