Sarah Sundin's Blog, page 378

July 23, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 23, 1944

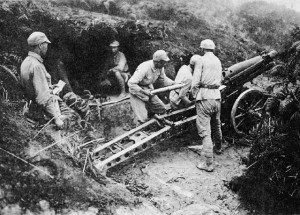

Artillerymen of Chinese 2nd Army in Sung Shan area of Burma. (US Army of Center of Military History)

70 Years Ago—July 23, 1944: In Italy, US Fifth Army takes portion of Pisa south of the Arno River. Chinese renew attack on Sung Shan, Burma in Salween region.

July 22, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 22, 1944

70 Years Ago—July 22, 1944: German SS glider troops land in the Vercors region of France and break up the Maquis uprising; over 800 French resistance members and civilians will be killed.

70 Years Ago—July 22, 1944: German SS glider troops land in the Vercors region of France and break up the Maquis uprising; over 800 French resistance members and civilians will be killed.

July 21, 2014

Port Chicago – The Mutiny Trial

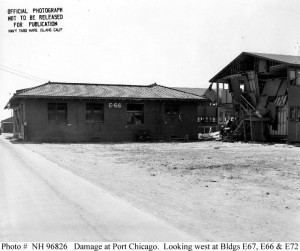

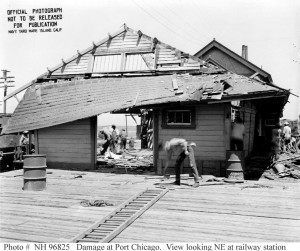

Buildings damaged by the explosion at the US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago on 17 July 1944 (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

In the worst Home Front disaster of World War II, an explosion at the Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California on July 17, 1944 killed 320 men, of whom 202 were black. The tragedy was followed by a work stoppage and a controversial mutiny trial. This sent ripples of change through the segregated armed forces.

These events are included in my third novel, Blue Skies Tomorrow. Previous blog posts discussed the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, the explosion, and the work stoppage. Today’s post covers the mutiny trial, and next week we’ll look at the aftermath.

Mutiny Trial

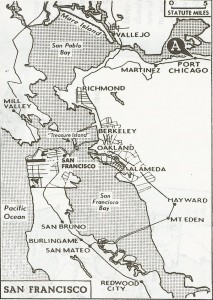

On August 9, 1944, 258 survivors of the explosion refused to load ammunition at Mare Island Naval Depot in Vallejo, California. After the threat of a charge of mutiny on August 11, fifty of these men still refused to load ammunition and were charged with mutiny.

A General Court Martial was convened by Adm. Carleton Wright, commander of the 12th Naval District, with a seven-member court led by Rear Adm. Hugo Osterhaus to act as judge and jury. The prosecution was led by Lt. Cdr. James Coakley. The defense team was led by Lt. Gerald Veltmann and consisted of five additional lawyers who each handled the cases of ten defendants.

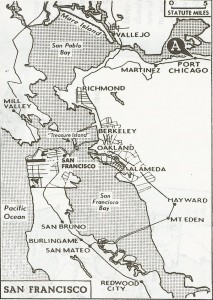

The trial was held in a Marines barracks on Yerba Buena Island (also known as Treasure Island) in San Francisco Bay.

Prosecution

ProsecutionOn September 14, 1944 the trial opened. Coakley argued that a strike was mutinous in time of war. He dismissed the defendants’ claims, stating, “What kind of discipline, what kind of morale would we have if men in the United States Navy could refuse to obey an order and then get off on the grounds of fear?”

The questioning of the defendants was loaded with racial language, and the prosecutors often disparaged the men’s honesty, especially when their spoken statements contradicted their earlier statements—although the men had complained that the transcriptions were inaccurate. One defendant had refused to load ammunition because he’d broken his wrist the day before the work stoppage and was wearing a cast. Coakley replied that “there were plenty of things a one-armed man could do on the ammunition dock.”

Defense

Veltmann quoted the official legal definition of mutiny: “a concerted effort to usurp, subvert, or override authority,” and argued that the men had never tried to seize command and therefore, were not guilty of mutiny. Since direct orders had not been given to each man, they could not be guilty of disobeying orders. The defense chronicled the discriminatory conditions at Port Chicago, the psychological effects of the explosion and cleaning up body parts, and the unchanged conditions they faced at Mare Island.

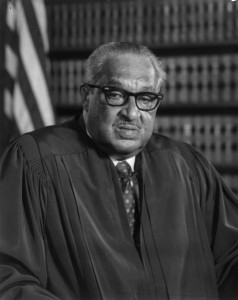

Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, 1976

Publicity

The Navy encouraged the press to cover the trial, and the NAACP sent their chief counsel, Thurgood Marshall (the future Supreme Court justice), who sat through twelve days of the trial. On October 10, Marshall held a press conference and stated that the prosecution acted in a prejudicial manner. On October 17, he issued a statement deriding the conditions in the Navy and specifically at Port Chicago. He believed the men were guilty of the lesser charge of insubordination and did not meet the legal definition of mutiny.

Verdict

On October 24, 1944, after deliberating for 80 minutes, the court convicted all 50 defendants of mutiny, including the man with the broken wrist and two others who had never loaded ammunition previously for medical reasons. All 50 men received 15-year sentences, and at the end of November they were imprisoned at Terminal Island Disciplinary Barracks in San Pedro, California.

Further Legal Action

On November 15, Admiral Wright reviewed the court’s findings and adjusted the sentences to 8-15 years. On April 3, 1945 Thurgood Marshall filed an appeals brief to the Judge Advocate General’s office in Washington DC. Concerned about hearsay evidence, the Secretary of the Navy asked the court to reconvene. They did so on June 12, 1945, but upheld the sentences. After the war was over, the sentences were reduced. In September 1945, one year was lopped off each man’s sentence, and in October the sentences were reduced to two years for all the men with good conduct and three for those with bad conduct. In January 1946, the Navy released all but three of the men—one remained for bad conduct and two in the hospital. The men stayed in the Navy and eventually received honorable discharges, but the felony convictions remained on their records.

Sources:

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny. Berkeley CA: Heyday Books, 2006.

The Articles of War. Washington DC: United States War Department, approved 8 September 1920. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/ref/AW/index.html, accessed 23 October 2011.

Department of the Navy. Articles for the Governance of the United States Navy, 1930. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1932. On Naval Historical Center website, updated 17 December 2001. http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq59-7.htm, accessed 23 October 2011.

Marshall, Thurgood. “Statement on the Trial of Negro Sailors at Yerba Buena, September 24, 1944.” On Organization of American Historians website: www.oah.org/pubs, accessed 20 November 2007.

Today in World War II History—July 21, 1944

US officers plant flag eight minutes after troops begin landing on Guam, 21 July 1944 (US National Archives)

70 Years Ago—July 21, 1944: US Army and Marines invade Japanese-held Guam with heavy opposition.

July 20, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 20, 1944

Col. Count Claus von Stauffenberg and Adm. Karl-Jesco von Puttkamer greet Hitler at Rastenburt, 15 July 1944, 5 days before assassination attempt. (German Federal Archive)

70 Years Ago—July 20, 1944: Operation Valkyrie – German officers attempt to assassinate Hitler, led by Col. Count Claus von Stauffenberg; the following coup attempt also fails. Movie premiere of Since You Went Away, starring Claudette Colbert and Joseph Cotten.

July 19, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 19, 1944

Japanese-American troops of 100th Infantry Battalion of US 442nd Regimental Combat Team resting on the side of a street in Livorno, Italy, 19 Jul 1944. (Hawaii War Records Depository)

70 Years Ago—July 19, 1944: Democratic convention opens in Chicago; President Roosevelt will be nominated for an unprecedented fourth term on July 20, Sen. Harry Truman will be nominated for vice president. US Fifth Army takes crucial port of Leghorn (Livorno), Italy with little opposition, but Germans have destroyed harbor.

July 18, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 18, 1944

Kuniaki Koiso, prime minister of Japan, 1944-45 (public domain)

70 Years Ago—July 18, 1944: Japanese Prime Minister Gen. Hideki Tojo resigns with his whole cabinet and is replaced by Gen. Kuniaki Koiso.

July 17, 2014

Port Chicago – The Work Stoppage

Damage to depot at US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago from 17 July 1944 explosion (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

In the worst Home Front disaster of World War II, an explosion at the Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California on July 17, 1944 killed 320 men, of whom 202 were black. The tragedy was followed by a work stoppage and a controversial mutiny trial. This sent ripples of change through the segregated armed forces.

These events are included in my third novel, Blue Skies Tomorrow. Previous blog posts discussed the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, and the explosion, today I’ll cover the work stoppage, and over the next couple of weeks we’ll look at the trial, and the aftermath.

Survivors

After the July 17, 1944 explosion claimed 320 lives, most of the survivors were taken to Port Shoemaker in Oakland. However, two hundred men remained to help in the grisly clean up. By the end of the month, reconstruction began, and the first berth on the new pier opened September 6, 1944. Survivors’ leaves were granted to the white, but not the black survivors.

Congress met to decide on payments to beneficiaries, usually $5000. However, when Senator John Rankin (D-Mississippi) heard most of the beneficiaries were black, he demanded lowering payments to $2000. Congress settled on the insulting amount of $3000, which applied to white beneficiaries as well.

Since the war continued and the Navy’s need for ammunitions in the Pacific had not diminished, three of the surviving work divisions (all black) from Port Chicago were sent to the main depot across the river at the Mare Island Navy Yard in Vallejo.

Work Stoppage

Work StoppageThe men remained jittery from the explosion that had killed so many of their friends. No new training was given, no new safeguards were instituted, and the men served under the same white officers from Port Chicago. Tensions rose as they realized they’d be asked to load ammunition again. They knew firsthand the hollowness of the promise that the ammunition couldn’t detonate.

On August 9, 1944, the men were marched from their barracks at Mare Island toward the dock to load ammunition again for the first time since the explosion. Suddenly, the men stopped marching. They said they were afraid to handle munitions and they’d obey any order except the order to load ammunition.

Upon further questioning from the officers, of the 328 men in the three divisions, 258 refused to work. These men were confined to a barge, since the brig wasn’t big enough. For three days, the men remained under guard on the crowded, poorly ventilated barge.

The Admiral’s Demand

On August 11, the 258 men were gathered on the baseball field. Admiral Carleton Wright, commander of the 12th Naval District, addressed the men. He informed them that refusing to work in time of war was mutinous behavior, and that mutiny carried the death penalty.

The men were asked again if they were willing to work, and 208 said they were willing, but the remaining 50 refused and were taken to the brig at Camp Shoemaker in Oakland, California. These 50 men included two who refused because they were mess cooks and had never handled munitions before—one had a nervous condition and the other was underweight. Another man refused to work due to a broken wrist in a cast.

Interrogations

All 258 of the men who initially refused to work were interrogated at Camp Shoemaker, under armed guard and without counsel. The transcripts of their testimonies were often wildly inaccurate, but they were given no choice but to sign the testimonies.

On September 2, President Roosevelt recommended that the 208 men who agreed to return to work receive light sentences. These 208 were given Summary Courts Martial and bad-conduct discharges, and were docked three months’ pay. The 50 men who refused to work were given General Courts Martial with the charge of mutiny.

Sources:

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny. Berkeley CA: Heyday Books, 2006.

War Time History of U.S. Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, California. Washington DC: US Navy Bureau of Ordnance, 5 December 1945. On Naval Historical Center website. Accessed 2 October 2011. http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq80-3d.htm

Today in World War II History—July 17, 1944

Damage at US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, CA from explosion 17 July 1944 (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

70 Years Ago—July 17, 1944: Port Chicago Explosion: freighters E.A. Bryan and Quinalt Victory explode at the US Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, CA, killing 322 (mostly black sailors) in the largest home front disaster of the war; the resulting controversy exposes discrimination in the armed forces and leads to the desegregation of the Navy. In Normandy, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is injured by a strafing RAF fighter plane.

To read more about the Port Chicago Explosion, please see my blog series:

1) Segregation in the armed forces and the situation at Port Chicago.

4) The mutiny trial (posting July 21)

5) The aftermath (posting July 28)

July 16, 2014

Today in World War II History—July 16, 1944

Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers (US Army Center of Military History)

70 Years Ago—July 16, 1944: Sixth Army Group (US Seventh Army & French First Army) formed under Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers for Operation Anvil, the invasion of Southern France (later named Operation Dragoon). Lt. Cdr. Goodwin of New Zealand escapes Japanese POW camp in Hong Kong, swims to mainland China, the only man to escape from Hong Kong.