Briane Pagel's Blog: Thinking The Lions, page 11

April 21, 2016

FE FI FO FUM

Published on April 21, 2016 18:56

April 19, 2016

15,842 New Words: Shtum kids. Shtum. Dad's trying to take a nap.

“Must be tough,” says Jonah, “your father being so far away.”

“Must be tough,” says Jonah, “your father being so far away.”I shrug. Mum told me to keep shtum about the divorce.

Slade House: A Novel (p. 16)

__________________________

Shtum means to be quiet or noncommunicative. It's a Yiddish word of relatively modern origin, dating back only to the 1950s. Who knew they were still inventing words in the 1950s? It seems like we'd have had all the words by then.

To have a word recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary, there have to be several uses of the word, for a reasonable amount of time (generally at least 10 years). The OED looks for word-usage that is not immediately followed by an explanation of the word; their reasoning is that a word can't be in common usage if it has to be explained constantly.

Apropos of nothing, "almost" entered the English language in 1330. Just thought you'd want to know.

Published on April 19, 2016 17:21

April 17, 2016

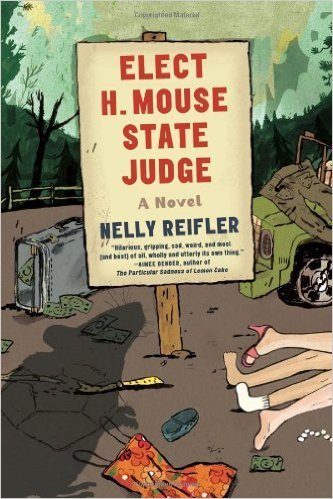

Book 29: Wherein a mouse makes me ponder the philosophy underlying my basic beliefs, as good parables do.

Elect H. Mouse State Judge is a weird book, and not just because the main character is a mouse running for judge.

Elect H. Mouse State Judge is a weird book, and not just because the main character is a mouse running for judge.The basic storyline is this: on Election Day, H. Mouse (a village councilman with some sordid events in his past) has his daughters abducted by religious fanatics. H. decides not to call the police because they would have to investigate him, to clear his name, and he doesn't want them to find out about some of the things he's done. So he hires operatives Barbie and Ken to track down his daughters, who are being held in a van by a toy called "Father Sunshine" and indoctrinated into something called "The Power" that is sort of a religious pyramid scheme.

That's all weird enough, but, as I said, the main character is a literal mouse, as are his daughters. Barbie and Ken are toys who live in their dream house with Skipper, and the rest of the 'people' are toys or small animals who nonetheless have county elections and run pornography and sex-slave shops and drive ATVs.

While I read the book (which is really short, just over 100 pages) I kept trying to figure out whether it mattered that H. Mouse was a mouse, that Barbie and Ken were actual toys instead of people named Barbie and Ken. For most of the book, I thought it didn't really matter, that it was just something thrown in to make the story weird, like how indie movies throw in some sort of magical realism or something, a way to in effect put a bird on the story

But after I finished it and thought about it for a while, I decided that making the characters be mice and lizards and toys actually worked really well on an almost subconscious level.

One of the best and most hauntingly creepy short stories I ever read was Melt With You by Emily Skaftun. You can read the whole thing here, but in summary it's a story in which everyone in the world has been reincarnated as knickknacks, garden gnomes, yard ornaments, and small toys. They have the ability to move and think but otherwise are limited to their physical forms. The story is told by a man who has become a plastic flamingo, together with his wife. They hop around on their one metal leg and try to make a new life until a group of religious fanatic garden gnomes starts a holy war.

It's a story that is terrifying on an almost primal level, mostly because of the ending, but also because of the sheer madness of the world it posits: a world in which people believe in God and do vicious things in his name, but a world which could in no possible way be one created by a God with any sort of gentleness or love in him, given how horrible that kind of ... "life"... seems to be.

If we believe in a God who is all-powerful and all-knowing, can that God be all-good, too, while evil exists? I know that's a question that's been pondered by smarter people than me. There is an argument about God's omnipotence that goes like this: If God is all-powerful, are there limits on what that power could be? For example, could an all-powerful God make a rock so heavy that God himself could not lift it? On the one hand, if he is omnipotent, then he can make such a rock -- but if he could not lift that rock, then he is not omnipotent.

I bring that up because both Melt With You and Elect H. Mouse State Judge deal with moral and religious issues in an offbeat way that allows them to discuss the message without being didactic. The message I think they are discussing is the question of whether everything happens for a reason. This is something that I believed for a long time, but have begun lately to question. In one sense, yes, everything does happen for a reason: earthquakes occur because the continental shelves are moving and create areas of friction. You end up working a certain job because of where you went to school and what you studied, which in turn is a result at least in part of where your parents decided to live and how they raised you. I often say that the only reason I live in Wisconsin is because my grandfather settled here in the 1930s, so my parents were raised here and stayed in Wisconsin which meant that I could get cheaper tuition and automatic admission to the Wisconsin bar when I graduated law school.

In that sense, my being a lawyer in Wisconsin happened for a reason, but that's not how people (including me, in the past) meant it. We meant that God had a divine plan that made it necessary for me to be a lawyer in Wisconsin for some higher purpose.

It's nice to think that. It's nice to think that people get cancer or have autism or are poor or die in a tornado at age 3 because it's all part of a greater plan. But is it true? Can it be true?

Do we want it to be true?

I mentioned in an earlier review of a book that the phrase in a song I found out I am really no one was sort of a relief for me: the idea that we are nobody and that our every action is not laden with portent can be a relief to people. Could you imagine living every moment of your life as though it was your last? Who would ever do laundry or clean the kitchen or show up to work? If we all act like we'll die tomorrow none of us would be blogging or reading blogs. Similarly, if everything you do affects the vast machinery of the universe in some important way, if choices you make this morning might mean that history turns out differently 50 years from now, the burden you would have!

I frequently point out to people that their absolute positions are absurd when taken to absolutes. When my brother said he would never go shopping at midnight on Thanksgiving I said "What if they were giving $1,000,000 to first 10 people through the door?" He said well of course he'd consider that -- so never went out the window.

Any position you take as an absolute can almost immediately be contradicted. I would never punch a baby in the face, you say. Unless doing so was the only way to save 100,000 people from immediate horrible death.

Everything happens for a reason is an absolute: it sets up the absolute meaning of every single thing we do, makes every choice meaningful, but at the same time it defeats the idea that choice is meaningful or even exists: if everything happens for a reason then you are freed from any moral responsibility for your choices. I shot those two bank security guards for a reason.

In Melt With You, many of the characters believe in God, but God has allowed them to have a startlingly freakish life -- and one that gets so much worse at the end of the story that I can't hardly think about it but also can't stop remembering it. It's easy to say everything happens for a reason but it's hard to see what the reason could be for that type of thing.

These are modern-day parables, fables, helping us understand our beliefs better by setting up something so outside the norm that we don't feel as though our beliefs are being challenged -- something that makes our minds close up -- even as the story itself does attack those fortresses of certitude we've erected.

H. Mouse is widely believed by everyone in the county to be a great moral character. He is a shoo-in for judge, almost hand-selected by the retiring state judge. They are wrong. There is a scene in the book where H. Mouse is sitting at his kitchen table, tired, and nearly drowsing. He is a day away from being sworn in and his daughters have not been found; he hasn't told the authorities about them, relying on Barbie and Ken to find them by his inauguration. He thinks to himself how sad he is with them missing, and for a moment tells himself that he would give anything to have them back safe and sound.

Then he realizes that, no he wouldn't because he opted to continue the election and not go to the police rather than have his past uncovered.

He is not a great mouse, H. Mouse. Barbie and Ken, as idealized toys that work in a morally ambiguous world -- at one point Ken suggests that if they can't find H. Mouse's daughters, they should go to the child slavers and buy him two more to fill in-- set up a contradiction in thought that helps demonstrate the moral vacuum people can exist in, convinced they are doing good even when they clearly are not.

In the end, as I've written this, I went from thinking this was a pretty good book to it being a great book. I think that by putting these horrible situations into the lives of mice and toys, Reifler has created a story that allows us to think about the meaning behind the story. If it were simply a basic story of a man whose daughters get abducted, no toys or mice or lizards, it would still be a pretty good story. But by putting it firmly into the unreal situation it is, Reifler makes the questions behind the story more real.

Reifler doesn't offer answers to the questions, either. Like Melt With You, and like many great books, the story just serves up questions. When I was in college, taking a writing course, the teacher said that one way of looking at writing is that we write the things we will never understand. I think the same can be said of reading.

Published on April 17, 2016 08:15

April 16, 2016

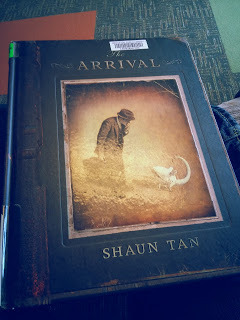

Book 28: OK so he's pretty good but can he draw a BULLET ANT? Didn't think so.

When I was 19 or so, or maybe 22, I took some art classes at the UW-Milwaukee. To get a bachelors' degree in political science, I needed a certain amount of art credits. So I took a couple of semesters of guitar, and a summer class in drawing.

When I was 19 or so, or maybe 22, I took some art classes at the UW-Milwaukee. To get a bachelors' degree in political science, I needed a certain amount of art credits. So I took a couple of semesters of guitar, and a summer class in drawing.I liked drawing almost as much as I liked guitar. But I was never very good at it. I can, if I really, really focus, make a pretty credible picture. Years ago, probably 15 or so, as a present for Sweetie I drew various scenes from New York City: the Status of Liberty, the lions outside the library, the Coca-Cola sign in Times Square, and a hot dog cart. They turned out pretty good.

But that took me weeks to do, and it was a ton of work, to come up with something that was merely okay.

Drawing is something I've never mastered, but really want to. I still work at it from time to time, and even when I'm just sitting and drawing quick pictures for Mr Bunches I try to work on having a style and making pictures my own. (we draw about 5 alphabets a week, with him writing the letter and telling me what to draw, and then he writes the word. We do animals [A is alligator, etc], foods, vegetables, and sometimes "phonics.")

One thing that holds me back is perspective. If I'm trying to draw something from an angle where you might not see part of it -- an airplane, say, where you wouldn't see the wing on one side -- I tend to draw the wing anyway, because it doesn't look right to me otherwise. So I have this plane that appears to exist in several dimensions at once, and I know I shouldn't do it, but I can't seem to help it.

One thing that holds me back is perspective. If I'm trying to draw something from an angle where you might not see part of it -- an airplane, say, where you wouldn't see the wing on one side -- I tend to draw the wing anyway, because it doesn't look right to me otherwise. So I have this plane that appears to exist in several dimensions at once, and I know I shouldn't do it, but I can't seem to help it.I was thinking about this when I sat down to read (?) the all-illustrated, wordless book The Arrival today at the library. We'd been out running errands (picking up a new light switch for the bathroom, and going to the used bookstore) and had then stopped off the local library, where they were going to do a "Crafty Kids" thing at 2:30; they do those about every other month, offering free craft projects for kids.

We got there early, and had about 45 minutes to kill, so while Mr Bunches played on the computer, Mr F and I went around looking through the books for something interesting. On the end of the "Teen Graphic Novels" shelf I saw The Arrival sitting, and I picked it up to see what it was all about.

Initially, I read the blurb on the back and then put it back on the shelf, ready to move on to the next set and see if there was anything to browse through there, but I didn't, right away, and instead opened the book up to glance through the artwork.

I was really enthralled with how gorgeous the book looked. So I sat down to read it while Mr Bunches played and Mr F looked at the lizard and sat patiently waiting for this to be over (Mr F is not a fan of the library, and spends much of his time there sitting in chairs, rolling his eyes when I suggest books to read, and making me take him to the bubbler for a drink.)

I'm glad I did.

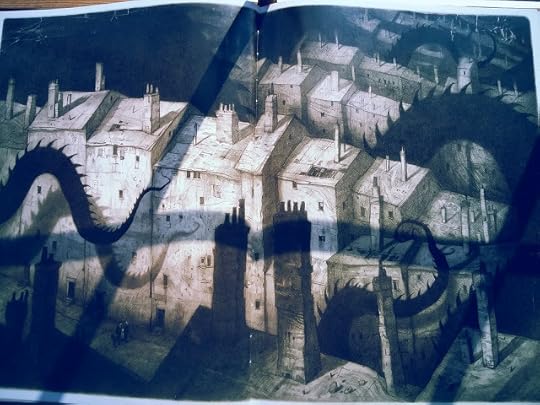

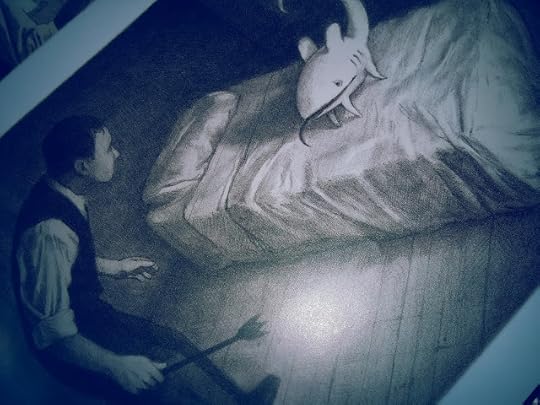

The Arrival tells the story, again, in pictures only, of a man who leaves his wife and daughter to go to a new country. The story seems to be a refugee story of sorts: as the man leaves and the wife and daughter head back home the city they are in seems overtaken with spiky tentacles looming all over it.

The book combines the sepia-toned early-immigrant feeling with a supernatural flair: buildings are fantastical or frightening, there are all sorts of strange creatures wandering around (apparently some sentient) and other, harder-to-describe stuff.

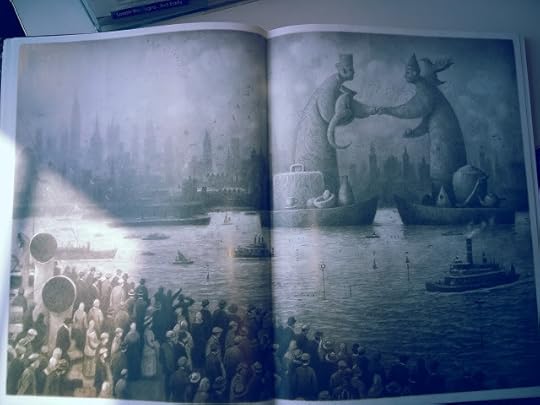

The man settles into his new life with a companion animal of sorts, and tries out a few jobs before getting set up in a factory, where he talks to a few other people about their background. (One man came from a startling country where giants turned everything angular. It has to be seen to be understood, really, but was spectacular and creepy.)

Overall, it took me about 40 minutes to read it because I ended up going through it twice: once for the story and once to go back and look at the pictures, and examine them in more detail. It's a book I might decide to buy one day, the kind of book that should exist in hard-copy format because it makes the drawing all the more amazing.

I definitely recommend it.

Published on April 16, 2016 19:27

If you had $47,500 you weren't doing very much with..

... you could build and launch your own satellite.

... you could build and launch your own satellite.For now, you can only go to low Earth orbit but someday you might be able to get your picosatellite out to the other planets.

If you want to use your satellite to look at Earth, though, you need to get a license*. If, though, you want to land your object on the moon or another planet, all you need is permission from the government of the country where you're going to launch from. The treaty which requires that you get permission also says you can't fly to the moon and claim it as your own.

*As part of that license you have to agree not to take any high-resolution images of Israel, in case you were wondering about how lobbying affects space exploration.

Published on April 16, 2016 03:09

April 15, 2016

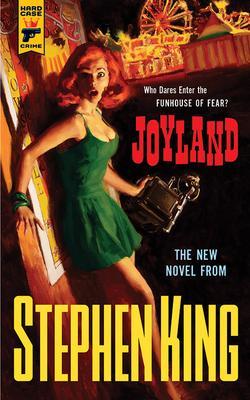

Book 27: You could almost foresee that the bulk of this would be about my feud with Stephen King

Joyland was the book that gave me a hissy fit about four years ago, when Stephen King announced that he'd written a book for Hard Case Crime, but that he would only publish it in paperback "at first," a move that generated tons of publicity and got King heralded as a guy who was saving writing for writers and reading for readers and so on blah blah blah. Even back four years ago King was saying he'd eventually make it available on e-readers after he'd soaked up enough profits from the lucrative publishers/top authors business model that still prevails today he'd given the readers an 'authentic' experience.

Joyland was the book that gave me a hissy fit about four years ago, when Stephen King announced that he'd written a book for Hard Case Crime, but that he would only publish it in paperback "at first," a move that generated tons of publicity and got King heralded as a guy who was saving writing for writers and reading for readers and so on blah blah blah. Even back four years ago King was saying he'd eventually make it available on e-readers after he'd soaked up enough profits from the lucrative publishers/top authors business model that still prevails today he'd given the readers an 'authentic' experience.King's decision to publish a book in 'hard copy' only generated a lot of praise and publicity, and also generated a backlash as people began pirating copies of it and giving him 1-star reviews on Amazon without even having read the book. Book piracy has generally been a nonissue for people -- have you even heard before today that people do it? I hadn't-- and not all authors and publishers were concerned about it. That article noted that King's Hard Case Crimes publisher shrugged off pirating, saying you have to rely on the goodwill of readers. My current all-time favorite author, Nick Harkaway, said technical solutions to stop book piracy were "silly." Harkaway thought pirating actually helped sales, which is an interesting point of view.

King's decision to forego e-book publishing for a while caused what can only be described as the least discriminating readers ever to download copies of a 2006 book also called Joyland, resulting in a windfall for the woman who wrote that other book. Stephen King even mentioned her on Twitter, and she started a blog about how she was spending her Stephen King money. (My book Eclipse came out about the same time as Stephanie Meyers' Eclipse and I got nothing. Pleh.)

Back in 2012 when I ranted about King's decision to only publish in paperback at first, I decided that it was far less about King's desire to let people have the 'authentic' experience of reading a pulpy crime novel the way he felt they should be read, and more about keeping big publishing and big authors together generating big sales for only a relatively few writers. I noted that the medium isn't the message, and that a book should stand on its own as a story regardless of the format it's read in.

But with Joyland, the medium was almost the only message. Not only did many of the stories about the book initially focus on the manner of its publishing, rather than its story or the Hard Case Crime series, but eventually Hard Case published even more 'collectible' editions: it was published in paperback for a year, then a series of limited-edition hardcovers, about 2,250 in all.

This is what I said in 2012, verbatim, about why King was publishing Joyland as a paperback:

What's really going on is some combination of contrived scarcity, added value, and a fight against Amazon and other indie booksellers like Smashwords.

Contrived scarcity is what Disney and the makers of Westvleteren 12 beer do (although the latter, being monks, deny that's what they're doing.) Disney won't let you buy The Lion King whenever you want; you have to wait until it comes out of the vault. The monks who make "the best beer in the world" carefully limit access to it, although when push comes to shove both open up their doors -- the monks started shipping their beer because they needed money to fix their abbey, which is understandable and they're still doing God's work but they're doing it for a profit.

Making your book available only through a small publisher and only in paperbacks guarantees scarcity, which can drive up demand. (Westlveteren sells for over $500 a case on eBay). It guarantees people pre-ordering the book and lines when King goes to the bookstores for signing -- and it guarantees stories about the book for months in advance, free publicity being the best kind, especially if it's authentic free publicity (which is why I'm not naming the book.)

I had no idea, then, that a year later Hard Case would deliberately play into the contrived scarcity of the book. This, of course, is probably why Hard Case got King to write a book for them in the first place; I'd have never read a Hard Case book if not for it being written by King, but now I'll go read a couple of their other ones, so the marketing worked.

I'm not against marketing. I'm the guy who suggested putting commercials and ads in books. I'm against marketing presented as authenticity. It's that kind of fake authenticity that makes every city in America have a cobblestoned minimall somewhere downtown, that makes people still buy vinyl records. The limited-edition copies of Joyland in hardcover are going for up to $250 online. If King's actual desire was to make people feel what it was like for him as a kid reading a pulpy paperback in his bed at night, why issue a $250 limited edition hardcover?

Stephen King's reputation as a writer has somehow managed to survive despite his many flaws. It was a sprawling wreck of a novel with a gross, out-of-place child orgy that gave away any suspense by its unnecessary and overly-complicated switching back and forth of timelines, burying an otherwise decent horror premise under a mess of literary tricks. His writing tends to be repetitious at times and he's often in need of a good editor. He writes, often, like a twelve-year-old; one of his books features a monster the characters call a shit weasel, and the monster is more unnecessarily gross than that name implies. He's written something like a kajillion novels, but they're an uneven bunch; for every The Stand or The Long Walk there's an Insomnia or Salem's Lot. And for a fun drinking game, try taking a sip every time King mentions a character wearing a 'chambray' shirt. I would like to send him an American Apparel catalog just so he'll have a guy wear something else.

But Stephen King has somehow risen above being Stephen King. His name is synonymous with horror writing in America, and he has also somehow become the de facto writer laureate of our country, despite his many poor writing tendencies. When King says something is good, people assume it is good. When he says it is bad, people assume it is bad. His reputation and influence seem to bear no actual relationship to his overall level of talent which I would say is on the higher side of average -- he's a B writer with the occasional stretch to A-level. He's like the baseball player that goes on a hot streak every so often but still has a .250 average.

In that sense, King is the perfect messenger for publishing's overall clamor that the medium is what is important: Stephen King the writer has become "Stephen King, Inc." the marketing force, and his decision to write a hard-case crime story made headlines before anyone even knew whether it would be any good. Most of the talk about Joyland has never been about Joyland as a story; it has been about Joyland as a product delivered by Stephen King, Inc., and just as Coke and Pepsi and Lucasfilm retain their credibility despite numerous fails, so does King.

Publishing exists, these days, to keep publishing in business. That is not really surprising: all businesses exist to keep themselves in business. What is amusing, if not amazing, is that publishing is attempting to keep itself alive by forcing people to consume its products only in one certain way. Think of another business that has insisted on that. When American carmakers kept insisting on big gas-guzzlers, they were undercut by auto companies that gave people sporty economy cars. Now they make electric vehicles and are pioneering self-driving cars. McDonalds has introduced salads. TV networks license shows to Hulu and the Beatles let Apple put their songs on iTunes.

Eventually, every business must accede to the desires of its public. The music industry continues to fight to keep people from listening to music the way they want to, and is losing money. Publishing keeps pushing Stephen King, Inc. (And "JK Rowling Conglomerated" and "John Grisham LLC") because these are reliable sellers that require little to no effort to market. Remember, not only did Stephen King's Joyland make a huge splash before it was written but people were so eager to buy a King novel that they didn't even bother to make sure they were buying the right Joyland.

I can see why the publishers wouldn't want to lose that. But at this point, it's almost completely not about the stories. I'm a King fan, mostly, and I can name maybe 10 of his books, on a good day. He's published sixty-two books. I doubt most people have read them all; I bet many people have read only 1 or 2, but even those people who don't read King know about him and could probably name 1 or 2 of his books. Stephen King is famous, at this point, for being Stephen King, and the flap over how Joyland was published, and the decision to focus on the manner of its publication, as well as to market the book almost exclusively based on the manner of publication, demonstrates that for many people, and many writers, and many publishers, writing is less than ever about the story.

Which in this case is kind of sad, because in the end, Joyland was actually a pretty good book. It benefitted from having a leaner, streamlined feel. It didn't end up being all bloated with nonsense the way so much of King's stuff is, and should be placed near the top of his books, for the story, rather than for being available in a $250 limited edition.

Published on April 15, 2016 17:36

April 13, 2016

Book 26: Also American readers can't handle the word a**hole but are okay with "kneebiter."

Year Zero is everything Futuristic Violence and Armada tried to be; those books failed at it, while Year Zero (mostly) succeeds.

Year Zero is everything Futuristic Violence and Armada tried to be; those books failed at it, while Year Zero (mostly) succeeds.Writing humor is hard, and writing scifi humor is harder still, because the moment you put a joke into your scifi book it's going to be compared to Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker books; Year Zero was billed as being similar to, or in the vein of, the Hitchhiker books, and it is, in a sense -- because they are both scifi books with a humorous tone and wacky hijinks. Beyond that, the books aren't really similar; Adams' humor exists on a level higher than any other book I can think of, with the multiple layers of jokes and asides and weird one-offs. There's nothing even half as clever as 'the most grautuitous use of the word Belgium' (which, as an aside, only exists as a phrase in the book for us because Americans are too prudish to let Adams use the word f**k .) But not every book has to be the greatest thing ever in the world to be enjoyable.

Year One is sort of oddly enjoyable; it sounds too specific and on-the-nose to be entertaining: the story revolves around aliens getting exposed to human music (specifically the Welcome Back, Kotter theme song) and being overwhelmed by how great our music is. So overwhelmed that they download, for 40 years, trillions upon trillions of copies spreading around the universe, only to realize one day that because of copyright laws the Earth is now owed something like 300 zillion times the entire wealth of the universe. That sets off a plot that honestly makes very little sense, alternating between proceeding along wholly-expected lines and veering into areas that seem to have no connection to what happened before. The hero is Nick Carter, who shares the name of a Backstreet Boy and the head of his law firm, which case of doubly-mistaken identity causes some aliens to select him as their lawyer to try to negotiate a license for the music, and to do so because a guild of entertainers succeeds in destroying the Earth 'accidentally' to avoid paying up.

Paying too much attention, or maybe too little attention, causes the plot to never quite add up; for example, there's a part at the end where one of the bad guys is insisting on getting the Guild's money back, and unless I'd missed it (I listened on audio) the Guild had never paid money in the story, so that didn't make sense, but it's the kind of story that doesn't really need to make sense. The details of why the aliens love our music so much and how that shapes them, combined with weird technologies and a sort of haphazard stop-and-go to the plot make the book more fun than I would've expected, and there are parts that are flat-out funny or amazing (the scene where Nick fights a group of photophobes in the dark ends in a way that is hilariously off-putting.)

The book occasionally gets a bit too specific about copyright laws; it's almost like it was written in part to be a primer on copyrights, like an infomercial for law clerks or something, but those parts are few and far between. That type of thing is to be expected, I guess: Rob Reid, the author, is a venture capitalist who got his start by founding Listen.com, which then turned into Rhapsody, the first online music streaming site. He founded that back in 2001, which is practically ancient history in Internet years. Shortly before he wrote this book, he gave a TED talk about how much of a sham "Copyright Math" is and argued that fighting music piracy could best be done not by draconian laws but by making it easier and cheaper to get music legally.

(Copyright laws, which I only know a little bit about, are a debatable bit of public legislation. Every country signatory to a treaty from the 19th century is required to protect copyrights for the life of the author plus at least 50 years. In 1998, the US extended this for most works to 75 years after the author's death. This was done, they said, to match European laws and to 'stimulate creativity,' the thinking being that nobody would bother to create something if they couldn't protect it for their entire life plus another lifetime after that. I think that's open to question. My own position is that copyright should be minimal -- maybe 5 or 10 years-- and that after that, anyone could use something created by someone else but they would have to share profits, providing 75% of the profits to the original creator during the creator's lifetime. That way, anyone could now (for example) use Luke Skywalker in their own books, movies, etc., but 75% of all the money earned would go to... Disney, I guess. So the incentive would be to create your own things, or to create some spinoff that's so wildly popular that you don't mind giving up 75% of the dough. Imagine, though: my system would mean Harry Potter would be fair game for everyone, which sounds weird to people, probably, but remember that 'Fifty Shades Of Gray' first began as a Twilight-fanfic, with the characters renamed. Everyone knows that's how it came to be, but because she changed a few details of the characters, Fifty Shades was allowed to exist.)

To be honest, I only listened to Year Zero because it was available and the books I really wanted weren't, but it hooked me pretty fast and I enjoyed it. I'd give it a solid three out of five; don't go out of your way to read it but if you like Hitchhiker or other sort of silly scifi you'll probably enjoy this.

Published on April 13, 2016 19:45

April 10, 2016

Book 25: So really I'm just sort of rambling here but go easy on me I've had about 3 hours sleep in the last 17 days.

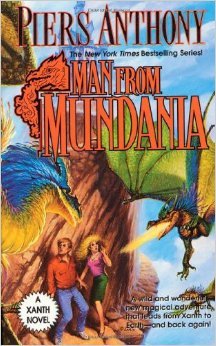

This was another Xanth book that it turns out I actually read long ago, although less of this one stuck in my mind, so I must not have read it very much. When I was a kid, I used to re-read books all the time. My old library card number at the Hartland Public Library was "4002," and in those days books were checked out with a card that they stamped with your library card number. In some books, there would be a string of 4002 4002 4002 on line after line, books that I loved so much I wanted to read them forever.

This was another Xanth book that it turns out I actually read long ago, although less of this one stuck in my mind, so I must not have read it very much. When I was a kid, I used to re-read books all the time. My old library card number at the Hartland Public Library was "4002," and in those days books were checked out with a card that they stamped with your library card number. In some books, there would be a string of 4002 4002 4002 on line after line, books that I loved so much I wanted to read them forever.I must have, I figure, owned Man From Mundania at one point, because I didn't check the Xanth books out of libraries (or at least I don't recall doing that) and because by the time this one came out I'd have been living in Milwaukee and going to college and I don't recall ever checking a book out of the Milwaukee library or the college library. So I guess I owned this book and must have lost it or given it away or sold it back when I sold boxes and boxes of books, five or ten years ago or something like that. I must have read it when I was getting to the stage of my life where I didn't have time to read and re-read books, where my reading time got limited by classes and work and parenting and being so tired sometimes at night that I can barely focus on anything, let alone on reading.

That's one reason I like these Xanth books, as well as some of the other lighter stuff I'm reading; especially the past week, I often am so exhausted by 8 or 9 that I'm literally bleary-eyed, and reading heavier, harder-to-understand stuff is almost beyond me. Between work and the boys and my asthma, sometimes it's all I can do to make it to 9 just holding my head up. It's easier to read stuff that I can just sort of float along on.

Anyway, the thing I really want to talk about with this book is the idea of a character refusing to believe what happens to them, and thinking it's a dream/trick/hallucination etc. In Man From Mundania, the storyline from Heaven Cent continues, with Princess Ivy using the "Heaven Cent" to try to find the Good Magician; the Cent sends her to Mundania, where she meets Grey Murphy, who likes her and decides to help her try to get back to Xanth even though he thinks she's delusional.

Grey doesn't believe in magic, or Xanth, which is understandable in that they don't exist in his world; he just goes along with Ivy because he likes her and thinks she's pretty. But they make their way back into Xanth, and Grey even then refuses to believe in magic or Xanth. He goes into a giant gourd, finds himself in a new place with a castle and plants that move and even a giant river of blood coming from a chained giant, and a magically appearing statue that is the Night Stallion who runs the world of dreams, and through it all Grey keeps thinking it's special effects or he's imagining it; it's not until about 1/3 of the way through the book, after Grey has met a centaur and goblins and a giant dragon and exploding pies that he starts to actually believe magic is real.

It helps with Grey's disbelief that his own magic is the ability to cancel or nullify other magic, but even then the disbelief began to bother me when it stubbornly stuck around; it went beyond what seemed credible for a character and began to feel like a plot device that had been stretched too thin.

The point of Grey's disbelief, in the story, is that it makes Ivy realize he really does like her, because he doesn't think she's a princess or magical, so Ivy knows Grey doesn't want her just for those things; but that could've been accomplished without making Grey seem quite so stubborn/dumb.

Like the "people forget technology and textbooks are a thing" of post-apocalyptic stories, the "I don't believe this because it's not possible" thing also strikes me as overused and kind of silly. I don't know that I've ever in my life been exposed to something so far outside of my experience or understanding of how things work that I wouldn't believe it; I can't think of anything like that offhand. So I don't know for sure how I'd react if something supernatural or unimaginable happened to me.

Although I have some clues, and those clues are that I'd probably accept it pretty quickly. Remember that time I thought we maybe had a poltergeist in our house because the door was flapping slightly back and forth with nobody in the room? I didn't, when I thought briefly that there was something weird happening, think oh I must be imagining this or that's not possible. I thought oh man this is cool that door is moving for no reason whatsoever.

So I feel like maybe I'd be pretty quick to just say yep this is happening and magic it up, but then I think about Bible stories, where God would appear to Moses as a burning bush or angels talked to shepherds, and I wonder what would happen if that kind of thing actually happened: not some low-level thing like a door moving for no reason, but a big honest-to-God happening.

I'm not so sure I'd believe that, or even talk about it. I think my first thought really would be that I was going insane. I remember reading A Beautiful Mind and learning that John Nash thought at times that he was a toe on God's foot; he really honestly believed that, among his other delusions. Back when my mom was first becoming a nurse she told us about a psychology class she had to take, in which one of the people was a case study. The guy thought that two pigeons that sat outside his window frequently were talking about him; also, he believed that one of the pigeons was Napoleon. Travis Walton still swears he was really abducted.

So if I really began to think something supernatural was happening to me, I suppose I wouldn't say anything at all to anyone, at least until it got scary -- like people who say God told them to kill someone or something -- or until I thought I had proof. But what would proof be if you're really crazy? Or hypnotized? (Note: I don't believe in hypnotism. We had one come to our school once and I am pretty sure that nobody who claimed to be hypnotized really was under some sort of hypnotic suggestion.) The guy who thought the pigeons were talking about him was convinced he had proof: he could see the pigeons talking about him.

I think the main thing to me would be someone else would have to see it independently before I would bring it up around them. Like if I thought a UFO came down in my yard, I doubt I'd say anything until someone else said they saw it, before I ever mentioned it. If someone else said hey did you see that table just lift up and tip over, I'd probably believe it really happened.

Although to be fair, then I might not automatically think ghost notwithstanding my previous instantaneous thought that we had a poltergeist. If I were sitting around and a table suddenly flipped over on its own, and other people saw it, I suppose I'd reach for more natural explanations, first: maybe there'd been a tremor? Or it was a trick rigged by someone? Or ... swamp gas?

The thing is, something that makes us unwilling to mention it to other people because it's so weird isn't going to have a rational explanation. When I see lights in the sky, I don't flip out because they're doing what lights in the sky are supposed to be doing: traveling steadily in one direction, or just being stars. But something like this:

doesn't have a rational explanation, and it would be about 1 minute into it that I'd be thinking okay I'm crazy and two minutes into it when someone else experienced it where I'd stop saying it was swamp gas.

I guess where I end up is that it's simply not that believable for characters to spend inordinate amounts of time saying I must be dreaming or That can't be real or whatever. I think Close Encounters of the Third Kind actually did a great job of showing how I imagine I, and most real people, would react: when Richard Dreyfus first sees aliens, he doesn't spend the next 14 years saying I must have been dreaming or it was all some sort of trick. When something's real it's harder to shake off, and reality can be shown by physical effects: a table flipping over or a sunburn on half your face or, in Man From Mundania's case, by magic actually working. So when characters continue to insist that it's all a fake or imaginary long after being shown that magic/spaceships/God actually exists, it starts to ring false. The more I read this year, the more I'm noticing all these little author gimmicks and tropes that really serve more to detract from the book than to enhance it. I think, like civilization-has-fallen-apart, the I-can't-believe-it trope really speaks to a dearth of imagination, which is a weird thing to say about a guy as prolific as Piers Anthony; like will-they-or-won't-they on romantic sitcoms, it's a false setup that gets played on too long because the writer can't drum up dramatic tension any other way. I suppose eventually I'll stumble across a book in which a character wakes up in a post-apocalyptic world where they live like medieval times, and he finds someone he's totally attracted to but also somewhat bugged by, and he just won't believe it and will have to repeatedly be convinced it's all for real. That book will sell ten trillion copies because apparently that's what people want in a story.

PS I had to stop watching that Close Encounters clip because that scene really freaks me out.

Published on April 10, 2016 19:14

April 9, 2016

Book 24: Yes, George, because of society.

Can we just talk about civilization for a minute? I'm not sure why everyone seems to think our civilization is so fragile that we're one bad week from savagery.

Can we just talk about civilization for a minute? I'm not sure why everyone seems to think our civilization is so fragile that we're one bad week from savagery. I've read a lot of post-apocalyptic books, some of them good, some bad, some mediocre like Station Eleven, and the common thread in many of them seems to be a serious doubt that humanity is worth a plugged nickel when it comes to rebuilding our society.

In about 90% of post-apocalyptic books, I'd say, humanity is reduced to scavengers, killers, weirdos, mutants, and generally inept people roaming strip malls and using cars as horse wagons and the like. And only in about 1% of those is there a good reason for the complete lack of civilization.

In The Passage and Lucifer's Hammer and Alas, Babylon and A Canticle for Leibowitz (to name a few) the reason society can't rebuild is because most of it has been physically destroyed by a comet or nuclear war or vampires -- but in those books there are enclaves of humans who did not forget that 2000 years of history has already existed, and so civilization as we know it is being rebuilt pretty rapidly.

Then there are the 90%, like Station Eleven, in which humanity is, well, silly. In Station Eleven, right at the outset, most of the world's population dies in a terrible flu epidemic; the collapse happens in about two or three weeks, leaving only a tiny fraction of people surviving. That's a setup kind of like The Stand, among others. Station Eleven starts in modern times, more or less today, and then everyone dies, and then the next chapter we've jumped 20 years ahead to see what the world is like then. It turns out it's annoying.

The people 20 years in the future live not in houses, teepees, log cabins, or caves, but in commercial buildings. Why? Who knows. It's never explained or discussed. People just live in airports or Hardees' or gas stations or whatever, completely ignoring the houses which are both existing and completely empty and not falling apart in most cases (because we're told that.)

The people 20 years in the future, post-flupocalypse, also use horses (but not very many), only they use the horses to pull around cars and vans that they've hollowed out of most of their equipment, for no apparent reason other than, I guess, once you've lived in a society where you knew a minivan existed you're completely incapable of making a covered wagon or other item that's easier to haul?

The people 20 years in the future use bows and arrows, and a few firearms, and their medicine is of the 'soak a needle in moonshine' variety, because medical textbooks seemingly also got the flu? Who knows. Granted, it'd be tough to do an MRI in a post-apocalyptic world but people would still know how to keep an environment clean and would have access to hospitals, with their large amounts of perfectly good scalpels and sutures and whatever else they have. But instead, EMTs live in abandoned hotels and sew bullets into people's wounds because it's too dangerous to try to dig it out.

*sigh*. And I haven't even gotten to the "Traveling Symphony," yet. The "Traveling Symphony" is sort of the focal point of the future in Station Eleven, a group of people who travel the same circuit around the Great Lakes, stopping in the towns along the way to perform musical numbers and Shakespeare plays. Most of the characters in the future are members of the Traveling Symphony, the existence of which is explained by borrowing a Star Trek quote "because survival is insufficient." At least I assume it's a Star Trek quote; I didn't bother looking it up.

The effect of all of this, the effect of Station Eleven as a whole, is, frankly, tedious. There were a lot of times I thought about just stopping the book entirely. It wasn't that bad, though, and I sort of wanted to see how the various storylines come together, which meant plodding through chapter after chapter of flashbacks, seemingly random events, and portentous moments that never got tied back together. The whole thing feels like its been done ad infinitum ad nauseum before, and that's probably because it has, and far better.

Mostly, Station Eleven is just boring. When it flits away from boring for a moment it becomes, as I said, annoying, and not just in the stuff I set out above. It's also annoying because the story feels almost random, as though it was meant to be the beginning of a far longer story; there's a plot that involves someone named "The Prophet" who turns out to be a character that barely had any importance prior to that, and by about the time "The Prophet" becomes a major character in this book, he's killed off almost immediately. Characters come and go, disappearing without further mention after they've been introduced, or showing up in such a way as to make a reader think he missed an earlier chapter when this character must have been introduced. Whole storylines are followed for no apparent reason, and because there are just so many characters, it's impossible to ever really connect to any of them, so when one dies (as many of them do) it's just sort of oh well I guess that person's dead too.

The author couldn't even be bothered to name many of the characters: the Symphony members are frequently referred to by their instruments, as in "The Clarinet." Annoyingly, not only does the author refer to them this way but their friends in the Symphony do, too -- only not everyone gets talked to that way. So there's "Kirsten" and "August" and "The Conductor" and "6th Guitar."

*sigh*.

After killing off most of civilization and jumping us forward, the book then (again, annoyingly) goes back to the more-distant past, following along with an actor, Arthur, for I'd say about 2/3 of the book, total: We get Arthur's childhood, his developing career, his whole first marriage, and most of his last year, smattered throughout the book, interspersed with more glimpses of the future, but now in the first few days after the epidemic, then 15 years in, then 3 years in, and so on.

There are enough common threads running through the story to make it seem like the author had something in mind here: Arthur's died on stage in front of a young girl in the play; that girl grows up to travel with the Traveling Symphony, performing Shakespeare, and carrying comic books that Arthur gave her before he died. The comics were drawn by Arthur's first wife, who plays a major role in the book for no apparent reason other than I guess to have drawn the comic. The comics also end up in the hands of Arthur's only son, who grows up to be the profit and who almost shoots Kirsten before he's shot in a deus ex machina moment that involves 0% emotional payoff. Arthur's old friend Clark is in the airport where Arthur's son briefly lived after the collapse, and he winds up showing Kirsten that some cities have developed electricity again. Meanwhile, the paramedic who tried to save Arthur has... gone to Virginia, where he has a kid.

The book just feels so scattershot and haphazard; it feels more like an outline for a TV series than an actual coherent story, and maybe that's what it was intended to be, but it's really not worth reading, at all.

Which brings me back to civilization, which is what I spent most of my time thinking about instead of bothering to pay all that much attention to the book. Specifically, why is it that people seem to think that anything other than global annihilation would leave us permanently in the stone age? If 99% of the world's population died this instant, that would still leave a phenomenal number of people, and lots and lots of resources. I've been wondering how quickly society might rebuild, and what level we'd rebuild to, quickly enough. I figure that if 99% of the world's population disappeared, there'd be some anarchy for a while, but there'd be enough people who know things like how oil wells work and how to run a refinery and such that the biggest bar to rebuilding society would simply be a lack of people to do it. I mean, if 1% of the people in the world were left but they were scattered all over the globe, it'd be hard to have enough people to get a fully-functioning city back up and running for a while, because cities take a lot of people to run them.

But I figure that at worst we'd spend most of our time at a level of technology roughly equivalent to the period of time from about 1880-1910 -- people could figure out how to make steam engines, and dig coal, and even get electricity going again. All that stuff was done by people who didn't have automation, computers, and the like. Heck, the transcontinental railroad was built with men digging through mountains with picks.

I get it, that having society collapse and then be only marginally inefficient isn't as dramatic as having everyone go all Mad Max, but if you want to tell a Mad Max story, give a reason for that to happen. I mean, even in The Passage [SPOILER ALERT] the army had generators up and running and a semblance of civilization going in the years after vampires killed pretty much everybody in North America in like three days.

Don't just say oh well society collapsed so people forget that steam engines exist. I won't believe that 20 years after a global epidemic there wouldn't be people who'd think hey man all I have to do is go to one of those old libraries and get a book about how Edison did things and we'd be back to about 1910 right there. Like any story things should have a reason for being that way, even if the story is totally fiction. "Suspension of disbelief" will let me imagine the flu killed everyone and a prophet can rise based on comic books -- but not that people would entirely forget how every single thing ever worked.

(Also, is shampoo good for 20 years? Because they find shampoo in one house and use it 20 years after the collapse, which means (a) shampoo has a long shelf-life and (b) people forgot how to make soap, which is something humanity has known how to do since 2800 BC.)

What really drove home just how dumb Station Eleven is was the comic book that gave this book its name. Station Eleven is a comic imagined by Miranda, whose death in the book is also completely devoid of emotion even though Miranda is about the only character who is more than a simple caricature of someone, and in Station Eleven (the comic) Earth has been taken over by aliens, and Station Eleven, a moonlike space station, has escaped with a small number of humans, to drift through space forever. The station is like a small planet but because it was damaged in the escape, the planet is mostly water and islands, and it's always twilight. Half the people on Station Eleven hide in bunkers "undersea" while the others live on the surface, and they're at war because the undersea folk want to go home to negotiate with the aliens while the surface dwellers want to stay here.

I'd have loved to have read Station Eleven, the comic. Station Eleven the novel was mostly just a waste of time.

Published on April 09, 2016 14:30

April 8, 2016

I had this moment...

Published on April 08, 2016 19:07

Thinking The Lions

Do you think people invented "Almond Joy" and then thought "we could subtract the almonds and make it a completely different thing?" or did they come up with "Mounds" first and then someone had a brot

Do you think people invented "Almond Joy" and then thought "we could subtract the almonds and make it a completely different thing?" or did they come up with "Mounds" first and then someone had a brother-in-law in the almond business? And anyway did you ever notice that the almond creates a little mound and that "Mounds" are flat?

I'm probably overthinking this. ...more

I'm probably overthinking this. ...more

- Briane Pagel's profile

- 14 followers