Briane Pagel's Blog: Thinking The Lions, page 7

May 25, 2016

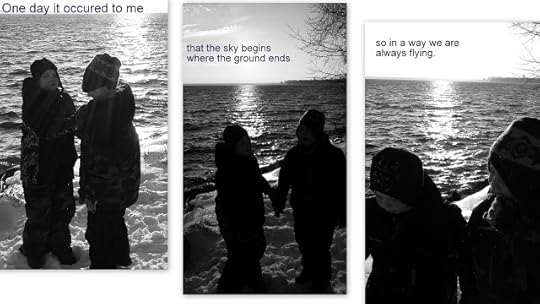

One day it occurred to me

Published on May 25, 2016 10:02

May 20, 2016

Book 37: Previously, On "Briane":

This was another of the Xanth books I actually had read in the past. This one was published in 1991. I don't have much to say about it this time; Piers Anthony is Piers Anthony. As I was finishing it up last night, Sweetie asked why I liked these books. I said they were sort of escapist reading, a bit in between the more serious stuff I read; it's easy to read books that are just fun and simply written, and some days -- especially this past week -- I'm just not up for heavier reading.

This was another of the Xanth books I actually had read in the past. This one was published in 1991. I don't have much to say about it this time; Piers Anthony is Piers Anthony. As I was finishing it up last night, Sweetie asked why I liked these books. I said they were sort of escapist reading, a bit in between the more serious stuff I read; it's easy to read books that are just fun and simply written, and some days -- especially this past week -- I'm just not up for heavier reading.One thing about this book: About the last 1/4 of it is simply a recapping of what's come before in the Xanth series. The book is essentially the history of Good Magician Humfrey, a major character in all the novels, and it tells why he disappeared several years ago. The basic plot of the book is that Humfrey is telling his life story while waiting for the demon whose magic makes Xanth exist, so that he can bargain to get his wife out of Hell; Humfrey hopes that when he gets to the present, Xanth will have to come deal with him, to avoid Humfrey simply telling his story into the future and saying he got the demon to agree. The latter part of Humfrey's life recounts everything that's happened in Xanth so far, making the final part of the book essentially a "Previously, In Xanth..." that I mostly skipped through. I suppose if you'd just picked up the series at book 14 it might be helpful, but does anyone do that? It felt like a way to pad out the book.

Anyway, I'm trying now to remember how many of these books I really did read. This one was even less familiar to me than the last couple, but I recalled having read it as I re-read it. Memory -- especially mine -- is a funny thing, although sometimes it bothers me how little I remember of some things; that, I guess, is what being 47 will do: make you worry about things that didn't used to worry you.

One of the things I like to do, though, is to think back to where I was, at a certain time, years ago. Question Quest was published in October, 1991. I probably would have bought it right away? 1991 was a long time ago, more than half my life. In October 1991, as near as I can recall, I was living at home, in between schooling for a while. I had gone to UW-Madison for a semester, done horribly, and dropped out because my parents didn't want to help pay for school if I wasn't going to study to be a doctor, and I didn't want to be a doctor. Two years later, in 1989, I re-enrolled, this time at UW-Waukesha, to study political science. On the 2nd day of the semester I got hit by a drunk driver, and missed that semester because I had to stay in bed for 2 or 3 weeks. Then, the following September I had to have surgery to fuse some vertebrae, so I wouldn't have gone back to school until winter 1990 or fall 1991; I don't remember which it was.

So I'm pretty sure that in fall 1991 I was still living at home, but it was around then that I moved out of the house and moved into an apartment in Milwaukee with two friends. But I probably would have been taking political science classes, and working at a gas station in town, as well as being a college radio DJ on Saturday mornings. 1991 is when I became a Buffalo Bills fan, and started to really like watching football.

Five years later would be October 1996; by then I had moved to Madison and enrolled in law school. This would have been the start of my second year, and would have been about the time my temporary job at the Department of Revenue ended, and I started working at the law firm where Sweetie was a legal secretary. 1996 would be when I started slacking off a bit in my exercise program. I weighed 170 pounds in 1996, and could run 6 miles in about 40 minutes, even though I was still a smoker, back then.

Five years after that in October 2001, we were living in a duplex in Middleton (just outside of Madison), with just the three older kids, no Mr Bunches or Mr F yet. I would have been at my old law firm, having started there a year before. At that time, the Department of Homeland Security was just being set up and Apple had released the iPod.

By October 2006 I'd been a nonsmoker for 2 years. The boys were a month old; I was still at my old firm. Sweetie had just gone back to work at the law firm she'd started working at after moving to Madison, and we would have been getting up at 5 a.m. every day to get everyone ready for school and daycare, then dropped the boys off at 7 to get to work by 8 so that we could leave work by 4:50 to pick up the boys by 5:30 in order to get home at 6, make dinner, do homework, and collapse into bed. After 6 months of that we decided Sweetie should quit her job and we'd make do.

We're still making do.

In October 2011, I was ending my first year as a partner at my old firm. I had an office on Capitol Square in Madison and had several lawyers working directly for me. I had the year before nearly died twice and had started to run for judge, but ended my campaign after Scott Walker got elected and being a judge became a terrible job. (Nearly all the county judges who were on the bench when he was elected have since retired.)

In October 2016 I...

to be continued.

Published on May 20, 2016 05:51

May 18, 2016

Balloon

Published on May 18, 2016 19:25

May 17, 2016

Book 36: OK this got kind of grim at the end.

I think sometimes fiction is better at explaining history than nonfiction.

I think sometimes fiction is better at explaining history than nonfiction.Nonfiction is concerned with facts. Fiction is about meaning, and impact, and making sense of things. Or, to put it another way: nonfiction is science, but fiction is myth. The stories we tell help us explain the world we know (or don't.)

The Mark And The Void is the first fiction I've read about The Great Crash, as I think of it, that began back in 2007. It's hard to write about something dramatic that you've lived through, even indirectly, as a general rule. A momentous event is simply, I think, too big to make much sense out of immediately. That's one reason there's been no decent stories that in any measure take place on or around or about 9/11. Writing decently about something, at least in fiction, requires that the person be able to put it in perspective, and it's hard to do that without something so big and new as 9/11, or The Great Crash -- especially because we are, literally, still living through them. The wars we are fighting now, as well as the privacy issues around cell phones and the indiscriminate drone killings authorized by the President, are all direct results of 9/11 and the Authorization For Use Of Military Force passed 15 years ago, a law so broad that it allowed the President to unilaterally act without Congressional approval in everything from Afghanistan to Seal Team 6's raid on bin Laden's compound to strikes against ISIS.

Similarly, The Great Crash has not ended. In 2014 the number of unemployment benefit claims roughly equaled the number filed in 2007. Our unemployment rate is 50% higher -- 6.7% in 2014 -- than it was in 2007. Only 62.5% of Americans are in the workforce; that's the lowest it's been in 35 years. Job openings are lower than they were in 2007. The 2007-2014 period of time was the worst period for job creation since the 1930s, during the Great Depression. And so on. I work in this mire: I spend great chunks of time every day helping people try to hold on to homes and stave off debt collectors, get out from under onerous student loans and away from subprime credit traps.

That's one reason I avoid stories about the events of 2007 and after; I (re)live them every day. Another reason, though, is, as I said, the lack of perspective, the lack of an ability to say something meaningful about the economic collapse we are still suffering.

The Mark And The Void takes place during the Crash, and is, essentially, about it, even when it seems as if it's not. The story focuses on Claude, a French banker who works in a global bank's Dublin headquarters; the bank has survived the initial wave of the collapse because it was stodgy and stable and the CEO wouldn't allow investments into risky and unusual financial tools.

The story is this: Claude is followed for a while by a 'man in black,' who turns out to be a writer named Paul. Paul, who had a very minor book released 7 years earlier, tells Claude he wants to write a modern-day Ulysses, and use Claude as his Leopold Bloom, and asks if he can shadow Claude for a while to get the details of his life. Claude's bosses okay this, and Paul moves in to the bank. At the same time, the Bank (Bank of Torabundo, referred to as "BOT" throughout the book) has replaced its CEO with "Porter Blankly," a dashing sort of Richard-Branson-esque leader whose directives to his staff are couched in inspirational riddles and say things like "Think counterintuitive."

As it turns out, Paul is not a writer, really, and he is using Claude to get inside the bank to try to rob it; Paul doesn't know that investment banks, like BOT, don't have 'deposits,' and so there is no safe to rob. By the time Claude figures this out, he has been ensnared by Paul; Paul's attempts to convince Claude the book was real and describe some plot get Claude to start falling in love with a local waitress (Paul's twist in the book he proposes) and Claude decides he wants to help Paul write his book after all.

It's hard to boil everything that happens down to an explainable level; the book has several different plots going on and they overlap; Claude's history (raised by a blacksmith, in the 1980s, in Paris) is gone into, and subplots abound.

Then there are, too, the scenes that seem de rigeur for books like this, books like The Great Gatsby and Bonfire Of The Vanities (this book is the equal of both): bankers partying at strip clubs, bread lines, hedge fund offices opulent beyond measure, squalid apartments for middle class people. Those are the trappings of a book like this and need to be there.

What really hits home in The Mark And The Void is the way it manages to capture all the problems that led to the Crash (and continue it) without being didactic.

Take the machinations of investment banks, the twists that lead governments to support them. BOT under Porter Blankly begins buying risky venture after risky venture, leveraging itself beyond all respectability and taking on more and more bad debt, and it's finally revealed that Blankly plants to make the bank "too big to fail." The idea is that if the investments pay off, the Bank will profit insanely. But if the investments go south, the various governments will have to bail out the bank to avoid further economic troubles.

It's both absurd and genius, the kind of thing that makes you think I don't want to believe this could actually be true but... Consider: after Iowa (!) became the state that first passed laws that led to megabanks, banks grew so large and so powerful that Citicorp in 1999 simply ignored federal law in merging with Travelers Group. As soon as the crash started, the current big banks -- JPMorgan, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America -- began purchasing all the banks that had just crashed. Those banks then received $95,000,000,000 in bailout funds (with Citigroup getting another $45,000,000,000.) (Meanwhile, 70% of applicants for the government's home mortgage modification program are denied.)

The absurd genius of that move is compared to Paul's efforts: throughout the book Paul tries one get-rich-quick scheme after another, giving various excuses as to why he simply won't write a book his publisher wants him to write: everything from the novel is dead to I have nobody who believes in me and so on. So Paul tries to start websites, bilks more money from Claude and comes up with an idea to steal a painting from the home of a banker boyfriend of a well-known author. The machinations of Porter Blankly and Paul are compared to each other, and in case there's any doubt about whether they're comparable, the characters mention that doing what Porter Blankly is doing at the track is gambling; do it with billions of dollars of other people's money and it's financial maneuvering.

One of the subplots involves Howie, a coworker of Claude's. Howie makes some shrewd moves and Blankly sets him up to run a hedge fund that is based on abstract Russian mathematics; Howie explains that the fund is premised on leveraging people's losses, and says that the more the fund loses the more money his investors make. When Claude protests that that's impossible, Howie says Claude just doesn't understand how advanced maths work.

"Beyond a certain point, complexity is fraud," writer P.J. O'Rourke once said. Consider the "credit default swap," a derivative invented in 1994. The basic idea is essentially interest against a loan default: a lender can purchase a 'Credit Default Swap," and if the loan defaults, the Swap seller pays the lender the value of the loan (usually) and takes over the asset. Simple, right?

Right. Except that anyone can buy a Credit Default Swap, even someone who has no actual interest in the loan. Which is to say: anyone (who is a billionaire or multinational) can buy a financial instrument that will pay them a sum of money if a loan (which they did not make and will not receive proceeds from) defaults. This feature led to there being more Credit Default Swaps in existence than actual loans they 'protected.' This is like several people having a life insurance policy on you, including people who you do not know and who do not know you; in the event that several people held a Swap on a defaulted loan, a system was invented to determine how much to pay each person -- less than face value but more than the cost of buying the Swap, one assumes. Credit Default Swaps were not tracked or monitored or reported. They still are not. Banks could buy Swaps on their own loans (although the instruments were FAR more sophisticated -- and complicated -- than this example) which meant that the Bank made money if you paid your loan, or if you defaulted.

So a bank might make you a loan of $100,000. If you pay it back, with interest, you pay the bank, say $200,000 over time. The bank runs a risk though: if you don't pay it back, they have to foreclose or sue, and that costs money. But there's an asset behind many loans, a house, say, so the bank has less risk: it will recover some money. Under these circumstances, banks have to be careful of the risk of a loan: make a bad choice and it loses $100,000, at least until it hires a lawyer and gets title to the house and sells it (but because of the realities of real estate, the Bank is unlikely to recover even it's whole $100,000 original investment.)

With trading of mortgages, banks became less concerned if you defaulted. Banks were paid loan origination fees, then could sell the loan for face value or slightly less: if they lent you $100,000, a portion of that (say 7000) would be paid to the Bank as an origination fee, so you only get $93,000 (or the Bank only shells out $93,000.) It can then sell the loan to another bank, for $94,000 or more, and make a quick $1000 on the deal -- without worrying about risk. Now banks can make riskier loans.

Swaps make that worse, because the bank can get a swap and pay (usually 1.5% of the loan's value per year) for protection. If your bank does that, for $1500 a year it gets insurance on the face value of the loan. If you default in year three, the Bank will have given you $93,000, paid $4500 in Swap fees, for total payouts of $97,500. Most of your payments in those 3 years are interest, so the Bank's principal is probably still about $90,000. The Swap holder pays the Bank $90,000 and takes over your loan. The Swap holder's investment is $85,500 -- $90,000 to the bank, less the $4500 it received in premiums. Assuming your house is worth $93,000 (100% financing was pretty common by 2007) the Swap holder could get a return of $8000 on its investment, less attorney's fees. (Most foreclosures are uncontested and the average attorney fee for such a case, at least in Wisconsin, would be under $1500.)

And this is just the surface of the complexity that exists, because Banks could buy Swaps in all sorts of loans. Suppose you know of 5 loans that are likely to default, each with face amounts of $100,000? Pay $1500 per loan -- $7500 -- and you have an interest in $500,000 worth of debt that, depending on how many other Swap holders there are, you will get a decent share of. Almost certainly more than $7500, it seems.

That's the system that we created, and is it any wonder nobody cared anymore if loans failed? Banks made more money if they did.

Against a backdrop like that, is stealing a priceless painting any less ethical, or ridiculous, as a method of earning money? Banks were too big to fail; homeowners were too small to succeed.

Like The Bonfire Of The Vanities, and like The Great Gatsby, The Mark And The Void perfectly captures the essence of an era, with an attention to detail and accuracy that is startling, but with a flair for the human, and the interesting, that makes the book less about what a hedge fund is than what kind of world did we create, and how will we live in it? The scene of Gatsby floating in his pool, after night after night of staring at the green light is no less tragic than the picture of Sherman McCoy standing in a holding cell in a damp suit with styrofoam peanuts stuck to his legs, and those two scenes are no more or less remarkable than the episode where Paul's son Remington finds an ant at a park and asks if he can keep him as a pet -- only to later have the ant escape, requiring the family to tear apart an apartment that is already falling to pieces and is half-finished.

For all that, it's a remarkably buoyant book, funny and fast-paced and somehow almost lighthearted. It's a story within a story within a tragedy, as if two wrongs do make a right and enough tragedy somehow becomes comedy again. Comedy is simply tragedy plus time, it's said. The Crash isn't over yet, but it seems somehow not to have stuck. The people of the Depression, of World War II, of Vietnam, were forever changed by their eras. My grandmother saved paper bags until she was 90. My grandfather had PTSD and used to wake up screaming about the "Japs coming up the beach."

Somewhere along the way, tragedy stopped mattering. By the 1980s, scandals and wars and crashes seemed to not matter anymore. There have been numerous financial bailouts, cuts in spending, recessions, bubbles, wars, and terrorism over the last 30 years. We are not numbed to them; they have simply stopped existing in the same world as we do. The world has grown so complex that even when we know where the trouble started, we never trace it back or address it. We simply shrug and make a sad joke about it and then let a new startup company move into the old space while trying to decide if we should vote to the millionaire or the billionaire to speak for the people.

Comedy is tragedy plus time? I think not. Comedy is any effort to understand humanity, because if we laugh hard enough we don't have to notice that nothing is funny.

It's a good book. You should read it.

Published on May 17, 2016 19:57

May 16, 2016

Here is another part of the problem with treating special-needs kids like circus attractions and safety hazards.

Following the incident on Saturday, there was another one on Sunday.

Following the incident on Saturday, there was another one on Sunday.I'm not going to discuss the Sunday one yet because I am waiting to receive some information.

Instead, I'm going to discuss the effects of what happened on Saturday, and on Sunday.

Yesterday, after the ending of the second incident, I had to run to the grocery store to pick up some milk and bananas for the week. I took Mr F and Mr Bunches with me, as we usually do.

When we go to the grocery store, Mr F likes to ride in the cart, if he can. At one store, they have big carts with seats for kids. At this store, they don't. But they have big carts, and Mr F can fit into them comfortably.

There is no sign or other rule that I'm aware of that says a kid can't sit in the space of the cart where the food usually goes.

Mr F gets a ride. I, frankly, get a slightly easier time at the grocery store because, as I said, I have to hold Mr F's hand almost constantly. Getting 3 gallons of milk plus bananas is tough to do one-handed, and steering a cart of any size is also tough to do.

So when we got there, I put Mr F in the cart, and we went into the store in the produce section. Mr Bunches wanted to buy a lemon (I don't know why, either) so we went over to the part of the produce department where there were lemons.

As we were going there, a store employee was mopping nearby. He glanced over at us, then took a longer look.

That's not unusual; we get sort of inured to people looking at us, because generally I am accompanied by Mr Bunches, who is usually talking (he was, in this case, talking about lemons) and Mr F, who taps his forks and makes his sounds and, of course, is a 9-year-old in a shopping cart. We get a lot of looks.

I'm fine with that.

Or I thought I was.

As soon as the kid looked a second time, I felt defensive. I thought the kid was going to tell us we had to take him out, or maybe that we had to leave. Or in some way get the manager or someone talking to us. I thought there was going to be a third scene in less than 24 hours, over something that we do all the time.

Mind you, nobody seems to think Mr F in the cart is a problem. Many of the employees at the grocery store we usually go to -- Woodman's, a fine store that deserves kudos-- know Sweetie and the boys on site. Whenever Mr F is there he rides in the cart, either in a seat or in the body of the cart. I had Mr F in a cart at Sears when I talked to the manager there one day. This day, later in the dairy section, a man waiting for us to get out of his way so he could get some milk said "I'd just like to be there when you run him over the scanner," and smiled as he nodded towards Mr F.

I have had no reason in my entire life with the boys -- nearly 10 years now-- to worry about Mr F being in the cart.

But I had no reason ever to worry that Mr F carried some forks or butter knives with him. Until Saturday and again yesterday.

So the end result of this, no matter what comes of the Sunday incident (which I'll provide more details on eventually) is that for at least a while, everywhere I or Sweetie go with the boys, we will have to wonder if the surreptitious glances or outright stares are more than curiosity or rudeness. We will have to worry that they will result in a scene of one kind or another.

I spent time this morning looking for new swimming pools we could take the boys to. They will not like the change, if we decide to change. But I will not willingly subject them to businesses that treat them like freaks.

Plenty of businesses are great. The Supercuts near us is so good with the boys that Mr F, who used to cry and howl through a haircut, now sits quietly in a chair by himself and lets them cut his hair. He whimpers a little but that's all. The grocery stores, libraries, toy stores, Panera, plenty of places are very nice to the boys and even pay special attention to them, which is nice.

These businesses made it their mission to single the boys out because they have special needs.

I won't forget it.

I can't forget it.

Published on May 16, 2016 07:42

May 14, 2016

He's not a 'safety hazard,' he's MY SON.

Mostly people are okay with the boys, and especially Mr F, who can present challenges to those who want to be okay with him. He's tough, at times: he can be loud, and he can be hard to control, and he can be mercurial (sometimes we say he's every emotion because he will laugh like crazy and then suddenly start bawling his eyes out.) But mostly people are okay with him.

Mostly people are okay with the boys, and especially Mr F, who can present challenges to those who want to be okay with him. He's tough, at times: he can be loud, and he can be hard to control, and he can be mercurial (sometimes we say he's every emotion because he will laugh like crazy and then suddenly start bawling his eyes out.) But mostly people are okay with him.That makes it so much harder when discrimination and ignorance show up and pick on him.

We took Mr F and Mr Bunches to "Dolphin Pool" today. This is one of Mr F's favorite things: it's an indoor zero-depth wading pool that he loves to go to. He sits in the hot tub, then he wades around. He will float, and roll on his back, and lately he has been going to the slide and walking up 2 or 3 steps before chickening out and going back down. I know he's going to make it up that slide one of these days.

"Dolphin Pool" is at a place called "Prairie Athletic Club." It's a health club on the other side of town that we get to go to because it's joined with the one we belong to in our neighborhood. We have been taking the boys to Dolphin Pool (so named because there is a statue of a dolphin on the edge of the pool) for 8 years now -- since they could first walk. We have been members of the club for eighteen years. Because I can't work out without dying, almost literally, the only reason the boys and I are still members is to use their pools, because swimming is Mr F's and Mr Bunches' favorite thing in the world to do.

Mr F stands out at the pool. He has to wear a wetsuit, because a few years back he would get bothered by how his swimming trunks felt, and take them off. So we bought a wetsuit for him to wear, because we can't have him taking off his trunks but we want him to swim. Do you know how much wetsuits cost? About $90. He's on his second one, because he's growing. We pay about $25 a month for the pool access, and have to buy a wetsuit. But swimming is important to Mr F. It calms him down and helps him relax, and he gets to be free.

Mr F is almost never free. Everywhere he goes, he's belted in (we have a special safety harness for use on the bus and in our car), or has his hand held. Nearly always. The only times Mr F gets to be free is when we're at a playground or a nature trail far away from roads or water. Then he can walk without someone holding him and not be buckled in on a 5-point harness like he's Evel Knievel, just for a trip to the library. This is because Mr F has little to no impulse control. He will dart away from you at a moment's notice. He also has absolutely no sense of safety. He either does not know, or does not care, for example, that cars will kill him. So if there's any chance he will get into danger, or trouble, he's under what I call "hand arrest."

Swimming, he is free. We don't hold him. He gets to swim and duck under and jump and splash and roll around, and if you could see him! He gets this faraway look in his eyes and a smile on his face and he laughs. It's making me smile as I write this.

This all means, though, that Mr F sticks out like a sore thumb in a pool. He's the only kid with a wetsuit, the only one jumping and laughing and rolling around. Even for kids in a pool, Mr F is a sight, the way he plays.

And he's the only one carrying 'tappers.'

I've mentioned 'tappers' before, I think. Mr F is always carrying something with him to tap. It used to be spatulas (we still have a drawerful of them). Then it was plastic coat hangers. For a while it was wooden spoons (we still haven't found the ones we used to have). Right now, it is forks, but a very special set of forks.

Mr F picks out his forks the way a surgeon might pick out his scalpel. If they get mixed up or (God forbid!) he loses one, the selection process for a new fork is a strenuous one. He will take 2 or 3 forks and hold them up, tap them experimentally on his chin or his hand, and then shift them in position, move them a bit, try a different combination, and so on. This takes about 15 or 20 minutes, at least, so we are very careful to keep his latest combination separate from the other forks, to spare him the trouble of having to do it again. (You can see how troubled he is when he can't make a combination that works for him. He gets sad and upset, hitting his head and crying. Since we don't know what a 'good' combination is, all we can do is suggest other forks or try to keep him from cracking his head on the floor.)

Mr F's absolute most favorite forks are these cheap plastic silvery ones from the Dollar Store. He loves these so much that the other day, when we wanted to get a surprise for each of the boys, we got Mr Bunches an "Imaginext Batmobile," ($24.99) and Mr F two sets of silver picnic forks. ($2). Mr F liked his present more.

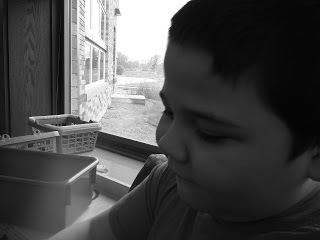

He holds these forks like this:

Always. That is always how he holds his forks. Then, once he has them set, he taps them lightly on his chin, or on his hand. Over and over and over.

I have a theory about why this is. With autism, everything is a theory. Nobody knows anything, really, about autism. Half the time we don't know anything about people like us: people who are able to communicate in abstract ways and explain concepts that are barely conceivable. We are so smart and yet we can't explain ourselves. Mr F is harder, since he can't tell us anything about what he's thinking.

My theory is this: Mr F needs the tappers to help him focus. Some people need something extra to help them focus in. I like to have background noise when I'm working: television works best, so many times when I'm writing a brief or working on research I will have Archer or something on in the background. I'm not listening to it, not really: it's white noise that helps me focus on what I'm doing, paradoxically. Without it the silence seems to crowd in on me, and I can hear my own pulse, it seems like, and I become aware of how my elbow itches and that my head hurts a little and my knee is bent too far... and I can't work. With some background noise, I'm fine.

Mr F is the opposite. Some scientists have theorized that one reason autistic people like the same routines and eat the same foods all the time is to cut down on the stimuli they experience; people think now that autistic people cannot sort out and ignore sensations, that every sound, texture, scent, sight, and taste are noticed and cataloged and experienced, every time.

Mr F is the opposite. Some scientists have theorized that one reason autistic people like the same routines and eat the same foods all the time is to cut down on the stimuli they experience; people think now that autistic people cannot sort out and ignore sensations, that every sound, texture, scent, sight, and taste are noticed and cataloged and experienced, every time.If you are reading this while sitting at your table drinking a cup of coffee, say, you are experiencing lots of sensations that your mind just categorizes away: sunlight over here, the chair creaking, the way the table feels under your skin, the mug's warmth: you don't notice those until they are really new. But autistic people, they think, notice everything all the time, and because of that they try to cut down on all the static. Mr F and Mr Bunches eat a narrow range of foods, because they can't stand all the newness of different flavors. Mr Bunches, for example, can tell the difference between "Crunch Berries" and the generic version of Crunch Berries. He can tell the difference between Crunch Berries that come in the box with Cap'n Crunch, and the Crunch Berries that come in the box of "Oops All Berries."

These are differences the boys cannot ignore. You or I probably wouldn't notice that slight difference, but they do, and they notice it every time. So they reduce the changes in their life to a minimum. They like routine, they like processed foods that taste the same every time, they will happily watch the same movie fifteen times in a row because that's the point it's the same movie.

Mr Bunches, like me, can exist in a world where a lot is going on: music, movies, games, people talking, and through it all he and I can focus on what we're doing. Mr F can't, though. He needs to cut down on the stimulation. He will bury his head in a blanket or under a cushion. He went through a phase where pictures on the wall bothered him -- so we have almost no pictures on the wall-- because there were so many different ones. He doesn't like to change blankets. He only wears a few kinds of clothes.

Even then, it's hard for him. That's why, we think, he sometimes loses it and starts crying and screaming. When he gets that bad, we cut down the interference even more: I take him for a ride in my car, which is a two-seater and small and he can feel the vibrations. He sits in his blanket and taps his forks and we listen to audiobooks and we drive the same route, almost every time, to help him calm down.

The forks, then, help him focus. That's my theory, anyway: by tapping them on his hand, or his chin, it helps him ignore all the stuff going on around him by focusing on this one little thing, these forks tapping against his chin. It's like biting on the heel of your thumb to help take your mind off the pain of your stubbed toe: if you give your mind something to focus on, it can help ignore things that are harder to take.

So you can imagine that he needs these forks at the pool. At the pool, there's the water and the noise and the kids running around and splashing and balls flying past his head and the hot tub starting up and people bringing pizzas to their tables and towels and a whole lot, and you can watch Mr F sometimes retreat from that by going over to the hot tub and wedging himself into a corner and closing his eyes, tapping his forks against his chin quietly.

Mr F has used forks as tappers almost exclusively for about 3 years now. He has brought them everywhere with him, including to Dolphin Pool, including last week when we went.

So I didn't think anything of it today when we went in and Mr Bunches went to the deep lap pool to jump in while Sweetie watched him, and I went over to the shallow pool to keep an eye on Mr F. I do this by hovering about 10-20' away from him: close enough that I can intervene if something happens, far enough that he doesn't feel crowded. If I get closer than 5-10', he keeps edging away from me because he doesn't like people too near him.

The pool wasn't especially crowded today. There were about 10 people in it, maybe? Or less. A few little kids, most of them over in the bigger, big-kids, pool; and some parents sitting around the edges looking at their phones.

Mr F had been swimming for about 20 minutes or so, and I was hanging out in the hot tub, when I saw a lifeguard come over by Mr F. Mr F was at that point standing at the bottom of the stairs to the slide, looking up them like he wanted really this time to go down the slide, and the lifeguard tapped him on the shoulder. I started over there, and Mr F walked a few steps from the lifeguard without looking at him. I wondered if the guard thought he was blocking the stairs or something. As I got there, the guard tapped Mr F on the shoulder again, and when Mr F walked away again, the guard looked across the room, rolled his eyes, and shrugged at someone, like what's up with this?

It SHOULD HAVE been obvious to anyone that whatever was up with Mr F, he wasn't a regular kid. Regular kids don't wear wetsuits to wading pools and carry forks around. Regular kids don't walk around making a bunch of nonsense noises.

Anyway, I was at the lifeguard and I said "Did you need something? I'm his dad."

The lifeguard said: "He's carrying forks and he shouldn't. It's a safety hazard."

I said, patiently: "He's autistic. He carries those forks because they help him focus. He doesn't hurt anyone."

The kid said "He shouldn't have them."

There were only a few kids in the pool. I said "Would it be okay if he kept them and I sat closer to him so nobody has to worry?"

The kid shrugged and walked away. I moved closer to Mr F and hung by him as he swam around, oblivious to what had just happened.

About 10 minutes later, I noticed a group of 3, maybe 4, people over on the other side of the pool. They were all wearing lifeguard clothes or club uniforms. One was the lifeguard I'd talked to. One was one of the women from the front desk. They were talking and looking over at me and Mr F, and pointing at him. Pointing at him repeatedly. And it was clear they were pointing at him because he and I were the only people in the direction they were pointing. They left about the time I thought they saw me looking at them. I can't be sure they left because of that, but they did.

I wasn't happy about this, but Mr F still had no idea what was going on, and we'd only been there about 30 minutes. I like to let him swim for an hour or so.

By this time, the pool was really pretty empty. There were two girls, about 5 or 6, sitting on the hot tub stairs. (I WILL NOTE that sitting on the hot tub stairs, and being under 12 and unsupervised in the hot tub, is in fact IN VIOLATION OF A RULE POSTED RIGHT THERE, but it did not appear these two girls had drawn the attention of the crowd of whispery pointers.) There were a few other kids over near the basketball hoops on the other side of the pool. Mr F was alone in the wading area of the pool.

I sat by him for a bit longer, and then he wanted to go in the hot tub. After making our way PAST THE GIRLS, ON THE STAIRS, we sat in the tub, Mr F in the middle section, me on the right.

After a few minutes, I noticed a guy walking by us, and looking at the hot tub. I noticed him because he'd walked past a few minutes before and had looked at us. Now he was doing it again. After about 2 or 3 more passes, he came and crouched by me in the hot tub. By then I was angry, because I didn't know who he was but I thought the crowd of club employees pointing at Mr F had drawn attention to him, and I didn't want some rando walking by eyeballing my son.

"Is that your son?" Rando said.

"Yes," I answered.

He was clothed. I was in a hot tub, in bathing trunks. He was crouching just over my shoulder, behind and to the right, and above me.

"I understand he's autistic, but he shouldn't have those forks," Rando said. He must have seen something bewildered in my face because he added "I'm Andy, one of the owners of the club."

So I said to this clothed man who loomed above me "He is autistic. He uses them to help him ignore all the stuff going on. He doesn't do anything with them. He just taps them."

"Does he have something else he could use here?" Rando Andy said.

"No," I said, trying to convey that we hadn't anticipated having to have multiple sets of tappers because he'd been bringing them here for about 3 years nearly every week without incident.

I also want to point out that this club is pretty fancy. In addition to 3 indoor pools it has a restaurant, and many people will bring their kids there around dinner and order pizza, which is brought into the pool by restaurant staff to eat poolside.

They bring it with forks and knives. Kids use those forks and knives.

Anyway, Rando Andy said "Would you mind taking them away from him? It's a safety hazard."

So many things ran through my mind but where I settled was: I am in a bathing suit. He is the owner of the club. I do not want to get us kicked out and have the boys not be able to swim anymore. The owner of the club is looming over me as I sit in a pool of water and asking me would I mind doing what he's telling me to do."

So I said to Mr F: Let me have your tappers, buddy. He started crying and tried to take them from me, but I gently held his hand and took them. He got upset and punched himself in the forehead. Rando Andy stood up. Thanks he said and walked away. I sat there, angry and wanting to get up and leave, but Mr F was still in the hot tub. He was upset, and looked sad, and tried to get his forks from me, and began trying to bite his wetsuit collar.

A few minutes later, as it turned out, Sweetie and Mr Bunches came over. Mr Bunches was tired and wanted to go and could we leave early? I said yes, and then on the way out told Sweetie what had happened. She was going to go storming off and yell at him right then. I told her to wait until we got there.

So we changed, and I gave Mr F the forks back, and we went out to the lobby where Sweetie demanded to see the manager, Rando Andy. He came out, and tried to get us to go into an office. I said quietly Right here is fine.

Then Sweetie lit into him. Without raising her voice but pitching it in that tone that tells you she would like to gut you like a fish, Sweetie denounced the manager for letting some parent goad him into making us take away Mr F's tappers. When Rando Andy said nobody complained Sweetie said that was a bunch of crap and someone must have because we'd been coming here for years and he'd been bringing his forks all that time and nobody had said anything. Rando Andy then pointed at me and said I asked him if he'd get the forks and he didn't seem to mind.

I said I was sitting in a hot tub with my son being told to by the owner of the club. I didn't want to make a scene.

Sweetie then denounced the ignorance and discrimination that would allow a little boy to be approached twice by a lifeguard who appeared completely uncognizant of the fact that this little boy in a wetsuit making strange noises was a special-needs kid, let alone have that little boy pointed at by a group of staffers -- Rando Andy tried to protest and say that didn't happen and I said it did, I was there -- and said that if their workers didn't know how to deal with special needs' kids they should get training. She pointed out that we'd been members for 18 years and had never caused a problem and said that she expected her sons not to be discriminated against when we came here in the future.

She started to leave. I told Rando Andy that if he wanted me or someone to come teach his staff about autism I'd be happy to do so. We have several people who have ... he started and I said then I expect in the future my sons won't be singled out like this, and we left.

So now, one of Mr F's favorite things in the world, Dolphin Pool, has been tainted. He will never know it, I hope. We're never sure how much he realizes about what's going on around him, so maybe he was completely unaware of all this today and just thinks I was being unfair when I took his tappers for a few minutes.

But we know it. We know that every time we walk in that door to take our boys swimming, it is likely to be a battleground -- or at least it will feel that way to us. We will be constantly nervous that Mr F or Mr Bunches will do or say something to attract attention from some other parent or staffer with no tolerance or understanding, and that the boys will again be the center of unwanted and unwarranted attention, that we will again have to make a scene to defend their right to exist on terms they can handle.

I'm not demanding special treatment. Mr F isn't carrying around weapons. He carries those forks everywhere. He is sleeping not five feet from me as I type this and the forks are in his hand. He takes them to the library, to the pool, in the car, sits with them as he watches television, everywhere. He has taken them to the pool at this club, and at the other health club. He has taken them to the Madison Community Pool. Not once has anyone said anything. He has never approached another little kid, never hurt anyone, never even dropped them in the way of anyone. If he does drop or set them down, Sweetie or I immediately pick them up. Not because it's a hazard -- it's a FORK -- but because if he loses one he has to go through a whole psychological ordeal to get a new set.

We have a little boy who wants to carry around a couple of forks with him. This little boy cannot talk. He had brain surgery when he fell of a counter and still has a scar from that, and because of that he cannot go on bounce castles, trampolines, or many other things little kids love. He cannot eat most foods. Because he is so worried about things he likes to feel enclosed and so even though he has a very nice bed with an extra-soft mattress on it and Spongebob Blankets, he sleeps in a closet I've removed the door from because he wants walls on three sides of him. He has to be watched when he goes to the bathroom and can't have the door closed because of that head injury. He is strapped into his bus seat with a safety harness, and held by the hand 99% of his life.

He wants to carry a couple of forks with him, and swim. This makes him deliriously, insanely happy, one of the few things that does in a world where most of the things traumatize or confuse him.

He will still get to do those things, and if he is lucky he will never know that each time we walk through those doors, Sweetie and I will have to again bristle for a fight, be ready to defend him, be ready to shield him from ignorant looks and overbearing Randos who want to throw their weight around on behalf of some spoiled-brat soccer mom worried that the weird kid will do something to her own perfect kids.

Mr F has never hurt anyone in his life, and never would.

But lots of people try to hurt him.

Published on May 14, 2016 19:28

May 13, 2016

I had this moment...

Published on May 13, 2016 07:58

May 12, 2016

Book 35: Secrets and lies.

The Rook is everything that Futuristic Violence & Fancy Suits and Midnight Riot wished they could be: a fun, intricate book full of great fight scenes, interesting mixes of science and fantasy and literary book, interesting characters, and an all-around great reading experience. It was so good, in fact, that when my time for borrowing the audiobook was up with 1/3 of the book left to go I couldn't wait to finish it and so I went and checked the hardcover out of the library.

The Rook is everything that Futuristic Violence & Fancy Suits and Midnight Riot wished they could be: a fun, intricate book full of great fight scenes, interesting mixes of science and fantasy and literary book, interesting characters, and an all-around great reading experience. It was so good, in fact, that when my time for borrowing the audiobook was up with 1/3 of the book left to go I couldn't wait to finish it and so I went and checked the hardcover out of the library.The Rook stars Myfanwy (the W is silent) Thomas, or someone not completely unlike her, as a member of the Checquy, a British superpower/supernatural secret service. It opens with Myfanwy opening her eyes to find herself standing in the rain, dead people wearing latex gloves all around her, and no idea how she got there or who she is. In her pocket is a letter. Dear you, it begins, and starts to fill in the gaps of what happened. The Myfanwy who starts out the book is not the Myfanwy that wrote the letters to the person who would take over her body after something terrible happened to the former-Myfanwy, and the new one has to not only adapt to not knowing who or where she is, but also the fact that a bunch of superpowered people are trying to kill her, and also that she is, in fact, about 3 rungs from the top of a group that helps protect Britain from supernatural threat.

It is an excellent book, reminiscent of Kraken by China Mieville or, possibly The Magicians crossed with X-Men. It pulls the reader along through the story, and never gets dull or dry; it's not that every scene is action packed, but that Myfanwy is such a great character, and the supporting cast around her (vampires, funguses, a group of Belgian medieval scientists called the "Grafters" who once tried to invade Britain using giant horse-spiders, a man (?) named Gestalt who is one brain that inhabits four separate bodies, each of which can think and act independently of the others, and so on) is phenomenal. There is just the right amount of humor, such as when tests have to be run on all the members of the Checquy to ensure they haven't become a Grafter pawn, and Myfanwy finds that she has to be licked -- by three of the best lickers the Checquy has produced, but there's lots of action and some intrigue as Myfanwy begins to unravel the plot around her.

Saying more would spoil the story, but I will say that the villains in the book are some of the most amazing (and intricately, phenomenally gross, at times, but in a fun way) that I've ever seen in a book, and by the end I was hoping there was a sequel to it. (There is, and I've put it on my TBR list.)

One thing the book got me thinking beyond how great is this story? (Seriously great) is this: Why would superheroes, vampires, magic, ultrascience, etc., have to be hidden? LOTS of stories have this conceit. In Kraken very few people know about such mysticisms as the fact that the ocean lives in a house in England and teleportation is real. In Harry Potter and The Magicians the general population has to be kept unaware of the existence of magic. In this book, the Checquy and its US counterpart (called the Croatoan in an allusion that goes unexplained in the book but if you get the reference it's pretty neat)(although as it turns out that mystery probably wasn't all that mysterious) have to remain secret, and that's never really explained.

I think in part each set of storytellers must have their own reason for keeping the superpowered worlds a secret from others. In Narnia books the secrecy and limited access served as a surrogate for Heaven (or Christianity) as well as a way of demonstrating that childhood is more magical than adulthood, for example. J.K. Rowlings' explanation for why magic was kept a secret from Muggles was this:

‘But what does a Ministry of Magic do?’

‘Well, their main job is to keep it from the Muggles that there’s still witches an’ wizards up an’ down the country.’

‘Why?’

‘Why? Blimey, Harry, everyone’d be wantin’ magic solutions to their problems. Nah, we’re best left alone.’

That doesn't really ring true, though. We have "magic" of a kind today: cell phones, MRIs, microsurgery, vaccines, spy satellites: they all work on principles that most people don't understand and which we couldn't recreate, or at least not easily. That doesn't keep people from wanting cures for everything and easier everything -- but saying we can't tell people about this revolutionary new heart surgery because then they'll be wantin' revolutionary solutions to their problems doesn't make much sense.

In The Rook the magic/superpowered aspects -- the world is sort of a mystical superpowered place -- is kept from most of the regular folk. Some of the powers are weird or gross, such as the man who can make acid fumes come from his skin; others are more acceptable (an American operative can cover herself with flexible metal). So that doesn't explain why all such things have to be kept a secret; it's not just that some things are gross or weird.

In some cases, keeping the secrets seems to be almost a commentary on society's divisions. In The Magicians one interpretation of magic is that it, like so many other resources, exists only (or mostly) for the 1%; people who go to Brakebills attend a school that's pretty much like an Ivy League college, and most seem to come from rich backgrounds. When they wash out of school they're placed in finance-companies, and magicians have fabulous wealth. The magicians even gain access to other worlds, entirely, something regular people and hedge-witches can only dream of. (In Narnia, too, it was generally upper-class people who could get to Narnia where, like The Magicians, they were kings and queens.) It's not hard to read keeping-magic-secret as a way to further separate the common folk from the elite.

That explanation doesn't hold in The Rook, though. It may be that it was just an idea to make it more exciting in the book, the idea that all this had to be kept secret, except that such a theory doesn't fit into the book at all: there are protesters outside the Rookery where Myfanwy works, but they're the usual wing-nuts who protect government agencies hiding supernatural things and nobody pays attention to them; other times (such as when a flesh-cube takes over a police station) the Checquy has very little trouble keeping people from knowing what's going on, despite the fact that this takes place in a world where, we're told, there are surveillance cameras all over and people have cellphones. So if you're going to make your superheroes secret to amp up the story, why not have the secrecy matter?

I considered whether it was just that everyone thinks, if I had power like that I'd have to keep it secret, but in a world where lots of people have powers, why would it be a secret? In our world, athletes don't work underground, the supersmart and superrich are not walking around incognito, and powerful politicians have Twitter accounts and Youtube channels: everything that serves as a proxy for superpower in our world is broadcast around the clock.

In the larger scheme, why would a government keep these things a secret, and how could they? One argument against any large conspiracy existing -- JFK's assassination, Pearl Harbor/9/11 being an inside job, the moon landing being fake-- is that it's almost impossible to keep any large scale operation a secret. If only a few people knew, then you'd have a better chance hiding the truth, but it still takes people wanting to be fooled. Bernie Madoff ran a fraud for decades because only a few people knew about it, and nobody wanted to question the good fortune.

Another thing is why would the government want to keep something a secret. I understand that if Bush let 9/11 happen so he'd have a justification to start a war in Iraq and do some regime change, the government wouldn't want to get that out. One could also assume that with the fact that there is very little difference between Democrats and Republicans in all the ways that count -- not talking social issues here -- the Democrats wouldn't rat Bush out because they too profit from a continuous state of war lasting 15 years now. (And counting!)

But Watergate, Iran/Contra, Monica Lewinsky, the Bay of Pigs, the Teapot Dome Scandal... controversies big and small get exposed even when everyone in power might benefit from not exposing them. It seems unlikely that vast conspiracies could exist and never be exposed.

If a government knew about superpowered individuals, and wanted to keep them a secret, could they? In The Rook people are born every day with new powers, and parents know about these (in some cases the kids are frightening.) Yet it appears that somehow nobody with any credibility ever talks about these people and the weird things going on. That seems like it couldn't happen, except think about all the secrets that lots of people know about yet they never become public. Hillary's private email server, for example. How long did it take before that became common knowledge?

In 1962, a double (or maybe triple?) agent almost got the US and Great Britain to launch nuclear strikes. Most people didn't hear about it for 20 years, until the story was declassified in 1992. In the 1960s the US Joint Chiefs of Staff prepared "Operation Northwoods," a plan to do fake terrorist attacks on our own citizens in order to give the US an excuse to go to war. The report was declassified nearly 40 years later. In 1968 President Nixon had his advisors tell South Vietnam to withdraw from peace talks, so that the war would continue and Nixon could be re-elected. The report was declassified in 2008.

The thing about those is: not only did very few people know about them for decades, but even after they were declassified they seemed to not make any news. I'm not sure how a plan to kill our own people to start a war wasn't a big deal, but that's the first I've ever heard of it.

The purloined letter was allowed to sit out in the open, with everyone ignoring it.

The Democratic debates this year were (allegedly) planned to reduce viewership so that Hillary wouldn't have to worry about Bernie or That Other Guy getting more name recognition.

For years both Bush and Obama routinely denied NSA electronic surveillance of US citizens' phone calls. A secret Foreign Intelligence court was created in 1978, and nowadays is called a "secret Supreme Court." This Court ("FISA") issued an order (in secret) in 2013 requiring Verizon to provide daily reports of call detail records to the NSA. These included domestic US citizen calls to other US citizens. (I used Verizon in 2013, and used the cell phone to make calls to clients that were confidential and protected by the attorney-client privilege.) The order was only made public when Edward Snowden leaked it. (The Court in its history has only denied 12 requests for warrants, in 38 years.) When this court criticized John Ashcroft for lying to it, and began requiring modification of requests to be ... more legal... the Bush administration simply ignored the Court and did its own surveillance, prompting one of the Secret Judges to resign. Judges on that court are appointed by the US Supreme Court Chief Justice, with no oversight or ability to object or interview them.

I don't think there are people with superpowers, or magic out there. If, though, there were, I have no doubt that not only would the government be able to keep them hidden from us, but also that when the news leaked out most people wouldn't pay any attention.

Published on May 12, 2016 18:54

Quotent Quotables: You know, I don't remember the story very well but I'm pretty sure the squid had a crush on Queequeg.

"I am serious, what does love have to do with anything we do all day long?"

"I am serious, what does love have to do with anything we do all day long?""Well, that's what he'd better work out," Ish says, "If he wants anyone to read his book."

"There are plenty of good stories without love."

"Like what?"

I think for a moment. "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea."

-- The Mark And The Void, Paul Murray.

Published on May 12, 2016 05:08

May 8, 2016

Book 34: "There is a rank due to the United States among nations which will be withheld, if not absolutely lost, by the reputation of weakness. If we desire to avoid insult, we must be able to repel it; if we desire to secure peace, one of the most powerfu

Great war stories give a person the feeling for what war must be like, a hard thing to do if the person being told the story has never even been in anything remotely resembling war. Movies can teach war through the visceral impact of film: the first 20 minutes of Saving Private Ryan, or the torture scene in Three Kings, or the city streets of Black Hawk Down.

Great war stories give a person the feeling for what war must be like, a hard thing to do if the person being told the story has never even been in anything remotely resembling war. Movies can teach war through the visceral impact of film: the first 20 minutes of Saving Private Ryan, or the torture scene in Three Kings, or the city streets of Black Hawk Down.Books have a harder time with this: as good as our imaginations are, they have difficulty synthesizing something that not only have they never experienced, but which is so far beyond the realm of our experience that it is, really, unimaginable. The best war books do not try to make a war in your mind, but instead pick out some feature of war and communicate that. Typically, what the best of these books show is how absurdly futile it is not just to fight a war, but to try to understand it. In Catch-22, this lesson is driven home by Yossarian's careful patching of the wrong wound on Snowden, and then being able to think of nothing more than there, there to say to the boy. In Slaughterhouse-5, the entire story shows the futility of trying to change anything: when Billy Pilgrim comes unstuck in time, he reveals that his entire string of experiences is not 'cause-and-effect' but simply random chance. His life didn't happen in any particular order because order doesn't matter.

Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk is a great war book. It is all the greater for not actually ever having any war in it, really.

Billy Lynn is part of "Bravo Squad," and the first thing to know about "Bravo Squad" is it doesn't exist. "Bravo Squad" isn't a military unit; it's real designation is more technical, but "Bravo Squad" is what the public calls the Bravo unit whose firefight in the Iraq war was caught by Fox news cameras; the resultant airing of that tape makes Billy and the rest of the Bravos instant heroes, and they're flown home for a two-week victory tour to shore up support for the war. (The book is set in 2007, a year that already feels like history.)

The book takes place on the day before Thanksgiving, when Billy is given 24 hours to spend with his family, and on Thanksgiving, when the Bravos are the guests of the (in this case fictional) owner of the Dallas Cowboys, set to appear at halftime with Destiny's Child, and we see all this through Billy's eyes as we get his thoughts on the subject -- not that his thoughts are very deep. Billy's barely out of high school and joined the Army to avoid jail after he was arrested for destroying his sister's ex-boyfriend's car, and despite from time-to-time more grown-up people leaning on him, Billy really is a kid and really is innocent: he's gone to war a virgin and had his first sexual experience on this tour.

There's very little plot to the book. What stories there are unfold slowly before exploding at the end: Albert, a producer traveling with the men, is trying to arrange a movie deal for them, having promised each Bravo $100,000 for the rights to their story. Billy's sister Katherine wants him to quit the Army and be helped by a group of lawyers who are fighting the war by trying to help men go AWOL.

The bigger story is Billy searching for meaning. Billy hooks on to anyone and everyone who seems able to provide him some deeper understanding of the world. He idolized "Shroom," a now-dead Bravo soldier whose stoner philosophizing got Billy hooked on Hunter S. Thompson books and thoughts of reincarnation. He throughout the book gets text messages from a TV preacher who he met at one stop and spoke to afterwards looking for guidance. He hangs on every word of his Sergeant, David Dime. But even his search for meaning is confused: he manages to get a chance to make out with a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader when, after some flirting, she tells him she is a Christian. She asks him if he is, too, and to keep the conversation going, Billy says he's searching -- a word he uses because he's heard it from other Christians growing up in Texas, not because he believes he really is.

Hidden from the loving American public is the fact that the Bravos are only home for two weeks, and that at 10 p.m. on Thanksgiving they will report back to post, and 36 hours later will be back in Iraq. So these soldiers wander around Texas Stadium, alternating between getting in fights with roadies, having brunch with millionaires, and standing at attention on a stage while Beyonce sings "Soldier" in front of a parade of cadets spinning rifles with fixed bayonets into the air and catching them. The negotiations over the movie swirl around them (at one point Billy learns that Hillary Swank is interested and wants to play him) and they sneak drinks of Jack-and-Coke or head out back to get high with a busboy from the buffet.

Back home, Billy's sister Katherine needs two more plastic surgeries to repair her face: she was nearly killed in a car accident and had hundreds of stitches in her face, causing her rich boyfriend to dump her (and leading to Billy's BMW-bashing.) Billy's mom is planning to take out a loan to pay Katherine's medical bills and those of Billy's dad, a right-wing radio host who had a stroke and is now wheelchair bound, mute (although it's not clear if he can talk but chooses not to). It's clear that Billy's dad hates Billy, for whatever reason, but the rest love him, while remaining true to their lower-middle-class roots: Billy gets a call from his family just after halftime, and what they want to know most of all is whether he met Beyonce.

The real point of the story is that none of this really matters. It's halftime for Billy, too: he and his friends are parading around in between the battles, having fun before going back to Viper FOB (Forward Operations Base) and a war that they don't really care about, but there's nothing better going on in their lives, either. Billy meets rich people and, trying to glean something from this experience, asks questions about how the Cowboys' owner got his money, how he bought the team -- only to goggle at the explanation. The world the rich move in isn't just economically out of the stratosphere for Billy; it's mentally and physically that way, as well: he spends the first quarter in the luxury box of the owner, looking down on the stadium before being kicked out for some dignitary or other. It'll get too crowded with the guy's security detail, the team owner says, and one Bravo says well we could protect him you know, and everyone laughs before packing the Bravos off to their seats near the sideline, in the sleet.

Everywhere Billy goes seems surreal, even though it's all depicted in the most basic terms. Shown into the locker room to get some pre-game autographs, Billy fields questions from the wide receivers about what it's like to kill a man, and the players later ask if they could come on tour with Billy for a week or two and shoot some Iraqis. When Billy says they'd have to join up and why don't they do that, the players laugh: We've got jobs, they say. We can't break our contracts. They go through the equipment room, with staggering numbers of shoes (3,000 pairs of sneakers a year, the trainer says the team goes through.) They get to do photo-ops with the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders (but when one Bravo asks whether they will meet Destiny's Child, they're told they're not a big enough deal to meet Beyonce.)

One of the most absurd, ridiculous, perfect moments comes near the end, when the Hollywood studios have gotten cold feet about the movie. (Ron Howard's company wants it, but demands it be set in World War II). Albert talks the Cowboys' owner into financing it, but the owner wants to drop the Bravos' advance to $5500 each, and then give them a share of the profits. Sgt. Dime gets angry and says no deal, and they're about to make a counteroffer when they're called back into the room, and Norm (the owner) says there's someone on the phone for Dime. It turns out Norm's connections have gotten him through to a General and Norm is going to have the General order Dime's men to make the deal. Dime gets on the phone, and Billy sees and hears Dime nodding, saying Yes sir and No sir and I didn't know that sir, before hanging up the phone, handing it back to Norm, and saying Come on Billy let's go. They leave, and when Billy asks whether the General ordered them to take the deal, Dime says no.

Turns out the General's a Pittsburgh Steelers fan and hates the Cowboys.

That moment sums up just how ridiculous war is: matters of life and death, rich and poor, winners and losers, get decided based on where someone lives and which team that man roots for. There's no grand scheme, no rhyme or reason to it, no purpose. Everything is the way it is because that's the way it is, and trying to change it is almost, if not completely, impossible. That's the lesson Billy learns on his long halftime walk before he reports back to the base and another 11 months of war.

But all is not lost. Billy is, after all, a war hero. So after meeting the President, being on TV, being told that an Academy Award winning actress wants to play him in a movie, and being featured on the TV in a close-up at halftime, Billy's greatest victory of the day ends up being when he finally gets some Advil for his headache.

Every gun that is made,

every warship launched,

every rocket fired signifies,

in the final sense,

a theft from those who hunger and are not fed,

those who are cold and are not clothed.

This world in arms is not spending money alone.

It is spending the sweat of its laborers,

the genius of its scientists,

the hopes of its children.

The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this:

a modern brick school in more than 30 cities.

It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population.

It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals.

It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement.

We pay for a single fighter with a half-million bushels of wheat.

We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people. . . .

This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense.

Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.

-- Dwight Eisenhower.

Published on May 08, 2016 19:15

Thinking The Lions

Do you think people invented "Almond Joy" and then thought "we could subtract the almonds and make it a completely different thing?" or did they come up with "Mounds" first and then someone had a brot

Do you think people invented "Almond Joy" and then thought "we could subtract the almonds and make it a completely different thing?" or did they come up with "Mounds" first and then someone had a brother-in-law in the almond business? And anyway did you ever notice that the almond creates a little mound and that "Mounds" are flat?

I'm probably overthinking this. ...more

I'm probably overthinking this. ...more

- Briane Pagel's profile

- 14 followers