Briane Pagel's Blog: Thinking The Lions, page 15

March 14, 2016

Book 17: So now I'm going to have to go read everything else David Mitchell ever wrote I guess.

I don't remember the last time I read a book as quickly as I just read Slade House. From start to finish, I read it in about 48 hours -- and the only reason I didn't finish it in 36 hours is I just ran out of time this morning with only about 5% of the book (the Kindle goes by % of book, not pages) left when I absolutely had to stop and go to work.

I don't remember the last time I read a book as quickly as I just read Slade House. From start to finish, I read it in about 48 hours -- and the only reason I didn't finish it in 36 hours is I just ran out of time this morning with only about 5% of the book (the Kindle goes by % of book, not pages) left when I absolutely had to stop and go to work.Slade House is by David Mitchell; most people might know him as the author of Cloud Atlas, which I will probably put on my list to read now, since two books I've read by him have been just brilliant. Last year I read his The Bone Clocks, and that remains one of the best books I've read in a long time: ambitious, expansive in scope, yet intimate in narrative, effortlessly combining scifi and 'literary' prose into something fantastic and heart-wrenching at the same time... The Bone Clocks should be on everyone's list.

Slade House isn't as phenomenal-seeming as The Bone Clocks but that's probably just because it doesn't try to be. That's not a knock: Slade House is superb; it just tells a smaller story. Instead of a massive epic, it focuses in on one particular detail.

Both books are set in what is essentially the same world: a world where 'atemporals' -- people who live outside of time in one way or another -- are at war with each other, in a quiet yet eternal way -- either defending regular humans or preying on them. The Bone Clocks spanned easily a half century and included something like 6 or 7 major characters and plenty of minor ones, telling the story of a particular episode of this war.

Slade House is sort of like a spin-off of that book. It tells the story of two particular atemporals -- bad guys -- who have set up an "orison" (it's a fancy word for prayer, but not used that way in the book) to help live forever. These twins have discovered that they can leave their bodies outside of time, and astrally project into other people's bodies, essentially living forever by possessing regular people; the catch is that they have to use the souls of certain kinds of people to power this effort, and at least every nine years they have to catch a new soul.

It's those repeated efforts, 9 years apart, that form the story of Slade House. The first person lured in opens the book; an autistic or at least somewhat different boy and his mother are invited to "Slade House" by what they presume to be a rich Englishwoman, in 1979. The invite's a fake, as the twins just want the boy's soul to power their orison for another 9 years. After that, each phase of the book takes place 9 years later, and each subsequent victim is in some way linked to the first character we meet.

It sounds fantasy-ish and horror-ish, but the book comes off as neither: it reads literary; all this hocus pocus and spooky stuff is presented in the mannerisms of a literary novel, and treated as matter-of-fact. Where a horror or scifi novel might be self-consciously so, David Mitchell somehow writes both in such a manner as to feel like neither.

That said, the book is extremely creepy, if not outright scary in parts. The actual scenes where the twins are themselves and are getting the souls are almost disturbing, and because each section is told in the first person from the perspective of the victim, the reader gets to suffer along with them. Each victim is lured in with an illusory scene of what they take to be "Slade House," the house where the twins lived for a while; the house itself no longer exists and everything the victim sees is in fact projected by the twins to trap them. Each scene becomes more macabre as the victim gets further in. One in particular, in which the victim thinks she's at some sort of college Halloween party, is downright frightening. I imagine it'll be a long time before I forget the image of her fleeing in her "Miss Piggy" mask, let alone what she saw that made her run. It was nightmarish, almost literally.

One thing Mitchell does really, really, well is he makes you care about his characters -- even, sometimes, the bad guys. In The Bone Clocks and in this book, some of the victims nearly made me cry; Mitchell doesn't make every victim purely sympathetic, though. One in Slade House is a jerk cop who tries to brush off having beaten up his wife before a divorce. But somehow his fate is so bad that even he generates some sympathy. In fact, Mitchell manages to craft a story in which even the soul stealing twins are not creatures of pure evil. If you can write a book in which two creepy evil twins spend a century stealing innocent souls to stay alive forever and yet at the end the reader is all well I mean but they're not all bad, THAT is good writing.

Slade House feels how I imagine Edgar Allan Poe would write a horror story if he were alive today: it has that feel, where there's plenty of actual scares but the real horror is the underlying terror of the fact that these things exist for the victims. I love horror stories, the more disturbing and scary the better. Slade House is one of the best I've ever come across.

Published on March 14, 2016 17:40

March 12, 2016

Mr Bunches Made Up A Whole Pretend Police Drama And Had Me Draw The Pictures...

Mr Bunches asked me if I could draw some robbers and bad guys for him...

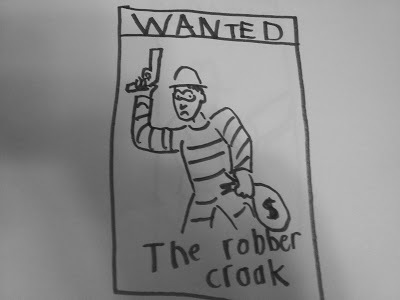

First was "The Robber Crook." As he named each one he described what they looked like and were doing, and then made the Wanted poster

Next up was

(He has a Silver Eye.)

Then

There is a bit of a story behind that one. Sweetie and I were watching Mission: Impossible one day last year, and Mr Bunches overheard a fight on the laptop. So he asked who the bad guy was and without thinking I said "John Voight."

Now, whenever he sees police sirens he asks if they are going to arrest John Void. (It wasn't until today that I realized he'd misheard me. But "John Void" is pretty cool.)

(Once The Boy was complaining about Dick Cheney and Mr Bunches decided -- quite correctly -- that Dick Cheney is a bad guy who sometimes the police are going to arrest, too. On a tour of the police station for school he asked me if the jail was where they put Dick Cheney. I said "They should."

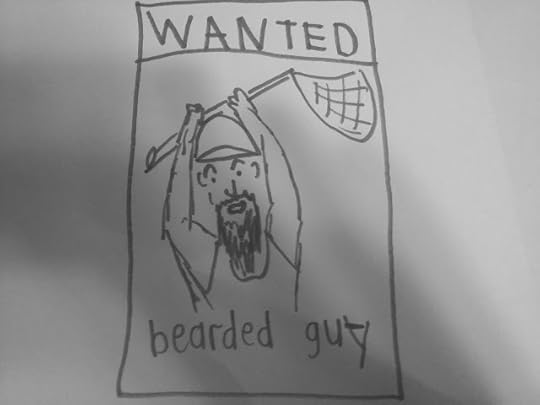

Then we had

His net is used to get the coins.

Then:

He is holding a sack of money under his right arm, in case you didn't get that.*

They are, from left to right:

Peter, Wilson, Zack, James, and Alex, who is James' son.

This is their car:

I've got to get this kid an agent.

First was "The Robber Crook." As he named each one he described what they looked like and were doing, and then made the Wanted poster

Next up was

(He has a Silver Eye.)

Then

There is a bit of a story behind that one. Sweetie and I were watching Mission: Impossible one day last year, and Mr Bunches overheard a fight on the laptop. So he asked who the bad guy was and without thinking I said "John Voight."

Now, whenever he sees police sirens he asks if they are going to arrest John Void. (It wasn't until today that I realized he'd misheard me. But "John Void" is pretty cool.)

(Once The Boy was complaining about Dick Cheney and Mr Bunches decided -- quite correctly -- that Dick Cheney is a bad guy who sometimes the police are going to arrest, too. On a tour of the police station for school he asked me if the jail was where they put Dick Cheney. I said "They should."

Then we had

His net is used to get the coins.

Then:

He is holding a sack of money under his right arm, in case you didn't get that.*

*Hey I don't see YOU drawing a sack of money and making it look all realistic.These guys are all being chased by:

They are, from left to right:

Peter, Wilson, Zack, James, and Alex, who is James' son.

This is their car:

I've got to get this kid an agent.

Published on March 12, 2016 17:07

March 11, 2016

Book 16: Out of Africa comes a story you won't forget.

I am a sucker for stories about, or set in, Africa. I don't think I've ever read a bad one -- from Into the Out Of by Alan Dean Foster to The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver to many, many more, if a story is set in Africa it's going to make my list to read.

I am a sucker for stories about, or set in, Africa. I don't think I've ever read a bad one -- from Into the Out Of by Alan Dean Foster to The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver to many, many more, if a story is set in Africa it's going to make my list to read.Bingo's Run is the latest Africa story, and it did not disappoint. I stumbled across Bingo's Run while I was browsing around for a new (audio)book after finishing The Golem and The Jinni, having never heard of the book or the author before. From the first line ("I am Bingo Mwolo. I am the greatest runner in Kibera, Nairobi, and probably the world") I was hooked.

Bingo's Run follows Bingo as he moves from being a drug runner to potentially an art dealer worth millions to almost dying: At the outset, Bingo introduces us to his life as a slum kid in Nairobi. His days begin with him and Slow George, his possibly-retarded friend, stealing some food from the market, then throwing rocks at a crazy bum at the dump before Bingo goes to his boss, Wolf, a relatively-higher-up in a drug trade. Bingo's job is to run drugs to various buyers around Kiberra and Nairobi, and he is, as he says, the best at it.

The story gets into motion when Bingo sees Wolf murder another dealer, and Bingo absconds with a briefcase holding $200,000. He ends up at an orphanage run by a crooked priest, and then, rather suddenly, adopted by a rich art dealer from the US.

To say more would spoil the rest of the story, which is full of twists and turns, double-crosses, arguments, sneaky maids, mysterious characters, corruption, and African legends. It's phenomenal. The story itself is gripping, but the atmosphere the author, James Levine, creates moves the story above 'really good' into great. Through Bingo's eyes we see the slums of Kiberra and the fancy hotels frequented by tourists, the insanity of artists in Nairobi, the grim reality of African jails and orphanages, and through Bingo's thoughts we get the confusion of a young boy trying to make sense of a world that's already chaotic and just gets more bewildering.

Bingo's own memories are parceled out through the story, along with what I took to be an African legend about the dawn of the human race, and his life is sad: he recalls spending time with his grandfather before the "gang boys" killed most of the village and forced his mom to flee -- and his memory of what then happened to his mom and how he feels about her is devastating. His friendship with Slow George is a wonder, and when the two get in an argument midway through the story I felt genuine anguish over it.

The ending to the story is, somehow, Gatsby-esque, and that's all I'll say about it: It evokes the ending of The Great Gatsby while being nothing like it at all, if that's possible.

)One thing that I find amazing is that the author was able to craft Bingo's life with what appears to be spot-on accuracy, from the language to the details of the city buses to everything, really; I'd assumed the author must be from Kenya or live there or something, but when I went to look up James Levine, I found out he's an English doctor who's now a professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic. It seems his experience with Kenya comes from working with impoverished children, and PBS says he's also a "slam poetry champion." (He also wrote a book about how bad sitting is for you, I saw, which means he would likely take a dim view of what is pretty much my only form of exercise.) Plus he invented the treadmill desk. Levine himself seems about as interesting as his books: he used to drive around Cleveland at 2 a.m. and talk to drug dealers about diabetes.)

But back to Bingo's Run. Here's how gripping the end of the story was. Every night, I take Mr F for his nightly ride to calm him down enough to go to sleep. The usual route takes 26 minutes; a slight hitch can turn it into a 32 minute ride. But after the first 32 minutes, the story was so close to the end and getting so great that I looped us around another 1 1/2 times so we could hear the end and find out what happened without waiting until tonight.

Bingo's Run is one of those rare stories that I think everyone should read, even if you wouldn't ordinarily go for this kind of book. It's full of incredible, memorable characters, and has at least five scenes that you'll never forget. I may just buy the hard copy of it to have around.

Published on March 11, 2016 19:07

March 10, 2016

Book 15: This Is A Review Of A Book In Which Stuff Happened.

I had this thought today. I thought There are two kinds of people in this world: those who finish their sentences, and

I had this thought today. I thought There are two kinds of people in this world: those who finish their sentences, andThen I decided that was too clever and I must have heard it somewhere, so I googled it, and found out that while maybe I hadn't heard of it somewhere, other people had had similar thoughts to that, so while my clever joke may or may not be my original work, it wasn't unique.

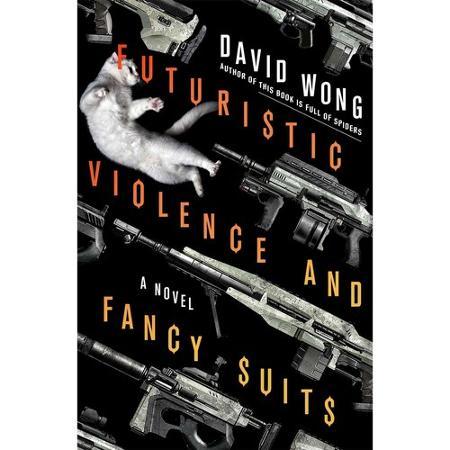

I was thinking about that just now because I just finished Futuristic Violence and Fancy Suits, a book which was also clever, but not particularly unique.

David Wong is the author of one of my favorite books of all time, John Dies At The End, and its sequel This Book Is Full Of Spiders: Seriously, Dude, Don't Touch It. Those two books both explore the adventures of two guys in a town where strange, world-threatening things happen, and only they can see it. They're inventive, weird, funny, memorable, great books.

Futuristic Violence is not. It's not even really close to how good Wong's first two books are. His first two books were 4 or 5-star books, really really good. Futuristic Violence is I'd say about 2, maybe 3, stars: solid effort, not a terrible book, but not particularly memorable.

I think the biggest flaw here is that the story seems so typical. I don't know, really, why I say that, except that as I read this book I kept thinking I'd read the same story, or watched the same movie, or seen the same thing, a thousand times before.

The basic plot is this: Zoey, a trailer-trash girl, gets set upon by a strange, psycho killer with mechanical jaws. She is mysteriously rescued -- or not! -- by some guys who intervene, and within a day or so she's off to "Tabula Rasa," a city where billionaires live essentially without law. She finds her dad was a billionaire himself, and that he is also dead. She hated her dad, who she'd only met twice in her life, but is [SPOILER ALERT] left his entire estate. The only problem is, there is a crazy thug named "Molech" who wants her dead, for reasons that ultimately are sort of ill-explained. Zoey eventually decides to work with her dad's inner circle, a gang of toughs called "The Suits" to fight Molech.

It all felt very cookie-cutterish and, for the first part of the book, somewhat annoying. Zoey is not a particularly likeable character. Wong has her spend about the first 1/3 whining, complaining, and generally saying she can't believe it and must be dreaming -- that latter one being a pet peeve of mine. Maybe I'm different than other people, but if I woke up tomorrow and learned that some relative of mine had left me billions of dollars, not for one second would I think I must be dreaming. As I've said before, I don't know anyone who has ever thought anything happening to them, good or bad, was happening in a dream. People don't work that way, and authors should knock it off. Just have people accept that life is real, okay? It doesn't add to the drama or fun or excitement of a book to have a character repeatedly say I must be dreaming.

Zoey's characterization isn't the only more-or-less-stock character. "The Suits" include an actual Asian woman who wears tight sexy clothes and is a computer genius, a large flamboyant black guy who is all muscle but also all heart, a Texan type who basically is described as a real-life Yosemite Sam, and "Will," who wears suits everywhere he goes, is always drinking scotch, and is the type of guy who is always three steps ahead of everyone else. Again, this all feels incredibly recycled.

The same goes for the villains, the side characters, all the rest of it: it feels like it's been done a million times before. Everything happens about as it's supposed to, with few surprises along the way. (One surprise was that Wong didn't fall into the usual trope of introducing a seemingly random character only to have that person save the day: at one point, Zoey is rescued, sort of, by a construction crew, and the episode felt so purposefully set up that I assumed at the end the construction crew would somehow save her or help her out. They never showed up again. Even with that Wong couldn't avoid temptation at every turn: a pair of white tigers mentioned frequently throughout the book show up at the very end at exactly where they're supposed to.)

Even though it's been done before, the book is written and paced to keep it moving. A generic action book with well-written action sequences and good pacing isn't the worst thing in the world. But it was a letdown after the comic excellence of Wong's first two books. Those books felt far more creative, fresh, and unique than this one.

I really wanted to like this book. I've been trying, in this review, to come up with some reason to recommend it or rate it higher than I should. I think, though, that's just residual good feeling from Wong's earlier work. I don't feel ripped off or like I wasted my time reading this one, but it's not like I'll recommend it to anyone, either.

In the end, it seems like the purposely generic title is, in fact, fitting: this is a book that you can in fact judge by its cover.

Published on March 10, 2016 19:51

"The secret of freedom lies in educating people, whereas the secret of tyranny is in keeping them ignorant."

In this article from The New Yorker about tax breaks for billionaires who donate to public projects, David Rubenstein, who is worth an estimated $2,600,000,000 (and who wrote his initials on the top of the Washington Monument after he bought half of it) says:

In this article from The New Yorker about tax breaks for billionaires who donate to public projects, David Rubenstein, who is worth an estimated $2,600,000,000 (and who wrote his initials on the top of the Washington Monument after he bought half of it) says:“The government doesn’t have the resources it used to have. We have gigantic budget deficits and large debt. And I think private citizens now need to pitch in.”

He was talking about how he regularly donates money to things that would be public projects otherwise, like the aforementioned Monument restoration after a rare earthquake in D.C.

Tax-cutting really took off in the 1980s, but the idea of tax cuts as economic stimulus goes back further: President Ford "reluctantly" signed the then-largest tax cut bill in 1975 to bolster the economy. As of 1960, the top marginal tax rate was 90%. By 1980, that rate was 70%, having fallen 20% in 20 years. In the next 8 years, under Reagan, the top marginal rate fell from 70% to 28%.

Which means that in 28 years -- 16 of which were under Republican presidents -- the top marginal tax rate fell by sixty-two percent.

Business Insider noted that there is no correlation between high tax rates and a sluggish economy; rather, there is a correlation between low tax rates and boom-or-bust economies. Since Reagan was elected, the government has spent

$2,091,000,000,000

...that's TWO TRILLION dollars...

bailing out private companies which failed when the economy went bust.

Meanwhile, there was no -- NO-- significant increase in spending relative to the amount of tax revenues received. Government spending, as a percentage of GDP, has remained relatively consistent at 18-21% since 1970. Nor has the tax-cutting produced greater revenues for the government (through more workers earning more money and hence paying more, albeit lower-rate, taxes.) That same chart shows that government receipts as a percentage of GDP have stayed the same over that time.

In other words, cutting taxes does not stimulate the economy in a healthy way. Cutting taxes does not help increase tax growth via the "rising tide" effect. Government spending has not skyrocketed over the past few decades.

Why doesn't the government have more money to take care of monuments and help feed poor people?

Because since 1960, the rich have been convincing the government to reduce their taxes -- and then to use what little money is left to bail out their businesses. At the expense of the middle-class, and the poor (two groups that are rapidly becoming the same group.)

Don't idolize billionaires. Idolize Robespierre.

Published on March 10, 2016 05:22

March 7, 2016

March 6, 2016

Book 14: What It Is Like To Be Human, Seen From The Eyes Of Those Who Don't Want To Be.

Whatever I expected from The Golem and The Jinni, I didn't get it. This was a book that kept surprising me in so many small ways. It was one of those rare, truly different feeling books that I like so much. I've only just finished it, three minutes ago, as my nightly ride with Mr F got done and we came up to sit in his room until he falls asleep, but I feel like I have to talk about it.

Whatever I expected from The Golem and The Jinni, I didn't get it. This was a book that kept surprising me in so many small ways. It was one of those rare, truly different feeling books that I like so much. I've only just finished it, three minutes ago, as my nightly ride with Mr F got done and we came up to sit in his room until he falls asleep, but I feel like I have to talk about it.It's hard to know where to start, so I'll just give a plot synopsis: A golem-- a clay being in Jewish kabbalah tradition, made to serve humans -- is created by an old, shady man, at the request of a rich furniture maker who is going to America. The book takes place at the turn of the century -- last century -- and the rich man wants the golem for a wife. Shortly after he brings her to life, he dies, and the golem ends up walking to New York along the bottom of the East River; there, bewildered (she's only been alive a few days) she's found by a rabbi who takes her in, knowing what she is.

Meanwhile, a tinsmith in Little Syria in New York works on a copper flask and sets free a jinni. The djinn in this book are sort of fire spirits, with great power, roaming the deserts. They're not Robin Williams' friendly sort of djinn. This jinni is trapped in human form by an iron bracelet around his wrist.

From there, the book quietly meanders along as the golem and the jinni learn about their new lives and begin to explore New York, eventually bumping into each other and striking up a friendship. Neither of them needs to sleep, so the golem has been spending her nights sewing clothes and looking out her window, while the jinni has been walking around New York getting to know the city and becoming something of a well-known man.

The first half of the book is deliberately paced: not slow, but methodical, as each sets into his or her own life, and as other characters are introduced and fleshed out; it's not until past halfway that the events that help set the plot in motion all come together. The golem has taken a job in a bakery, and her friend Anna has accidentally gotten pregnant. Anna's boyfriend is no great prize, and there is a confrontation that drastically shifts the direction of everyone's lives, in part because the golem's creator, Yehudah Schaalman, has come to New York seeking the answer to eternal life -- and his magic points him in the direction of the jinni.

The book is fantastically well-done; the magic is interwoven with the typical immigrant's-story details so skillfully that it feels real; it's not hard to picture a New York where a jinni and a golem could wander Central Park at night. From the tiny details about the two major characters (the jinni in his spare time sculpts tiny silver figurines based on animals from the desert, and cannot ever get an ibis he is working on to seem right, while the golem finds herself growing cold and stiff when winter comes) to the fleshing out of the secondary characters -- Mahmoud Saleh, a doctor stricken by possession from a minor jinn causing him to see everything as decayed and rotting, forcing him out of his profession into a life roaming the streets selling ice cream for pennies is one of the greatest side characters I've come across in a long time-- the book just breathes life.

What's interesting about the book, too, is that even though each of its main characters has been put into human form, they don't really want a human life. The jinni is always searching for a way to free himself from the iron cuff, to get back to his true form and return to the desert; he chafes at the need to hide his identity and slowly, if only partially accidentally, begins to tell more and more people, each one having a particular justification. This, of course, causes trouble with the man sheltering him, Boutros Arbeely, the tinsmith, who doesn't want the world to find out about the jinni, for fear of what they would do to him.

The golem, meanwhile, can read people's thoughts, and sits night after night in her lonely room, listening to the desires of people around her and staring out the window; she is so afraid of making any sort of mistake that might let people realize it is her that she rarely enters life at all -- and when she does, there is usually some terrible result. These are never her fault, but she blames herself anyway.

It's kind of a fascinating way to look at life, examining it through the eyes of two beings who reject it, each for different reasons. Before he was bound by a wizard a thousand years ago, we learn, the jinni was fascinated with humans, following a caravan through the desert and spending time trying to learn more about them. Now, thrust into the middle of a city full of them, he is constantly angry and trying to escape, not liking the limitations placed on him. The golem, though, is all too aware of what she might do to cause trouble; her first day in New York, she sensed a young boy was hungry and took a knish from the hand of a man nearby and gave it to him, nearly causing her to get arrested (or worse) until the rabbi stepped in. She has been repeatedly warned that she might accidentally destroy herself or those she loves, so she rejects humanity in order to save them (and herself) from her own actions, or mistakes.

There are so many dimensions to the book, it's hard to sum them all up. It's the kind of book that feels like a masterpiece, each little piece falling into place and making for a beautiful story. The finale is both surprising and masterful, with the end result being a long and detailed story about a quirky friendship in which each friend helps the other to accept, at least a little bit, some of the excitement in a life that is neither a prison nor and adventure.

Published on March 06, 2016 18:29

One of the things that makes civilization possible is that we all agree, as human beings with a certain level of respect for the dignity of the self and others, that we will generally ignore the slight differences, foibles, and mannerisms that make each of

On the phone with the doctor's office:

Me: Hello I would like to bring my son in to have his cough looked at.

Nurse: Have his cough LOOKED at?

Published on March 06, 2016 06:59

One of the things that makes civilization possible is that we all agree, as human beings with a certain level of respect for the dignity of the self and others, that we will generally ignore the slight differences, foibles, and mannerisms that make each of

On the phone with the doctor's office:

Me: Hello I would like to bring my son in to have his cough looked at.

Nurse: Have his cough LOOKED at?

Published on March 06, 2016 06:59

One of the things that makes civilization possible is that we all agree, as human beings with a certain level of respect for the dignity of the self and others, that we will generally ignore the slight differences, foibles, and mannerisms that make each of

On the phone with the doctor's office:

Me: Hello I would like to bring my son in to have his cough looked at.

Nurse: Have his cough LOOKED at?

Published on March 06, 2016 06:59

Thinking The Lions

Do you think people invented "Almond Joy" and then thought "we could subtract the almonds and make it a completely different thing?" or did they come up with "Mounds" first and then someone had a brot

Do you think people invented "Almond Joy" and then thought "we could subtract the almonds and make it a completely different thing?" or did they come up with "Mounds" first and then someone had a brother-in-law in the almond business? And anyway did you ever notice that the almond creates a little mound and that "Mounds" are flat?

I'm probably overthinking this. ...more

I'm probably overthinking this. ...more

- Briane Pagel's profile

- 14 followers