Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 6

October 7, 2024

Using evidence to justify policy and budget decisions

In 2019, the Foundations for Evidence-based Policymaking Act of 2018 (Evidence Act) was signed into law with bipartisan support. The goal of the law is to encourage cabinet-level federal agencies to use evidence to guide, strengthen, and justify their policy- and budget-making decisions. The Department of Veterans Affairs and its administrations, including the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), are required to comply.

The Evidence Act requires certain formal deliverables be submitted to the Office of Management and Budget on routine cadences. However, beyond the law’s formal requirements, VHA developed the strength of evidence checklist to strengthen the legislative and budget proposal processes. The goal is to ensure that VHA offices are using evidence to justify any changes they’re proposing to current law and/or budget lines. VHA considers this the Evidence Act “in action.”

The Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC) spearheaded the checklist’s development and wrote a short policy brief about it. In the policy brief, PEPReC discusses the domains of evidence included in the checklist, how VHA uses it in the legislative and budget proposal process, and the routine improvements made in its early years.

Read the policy brief here.

PEPReC, within the Veterans Health Administration and funded in large part by the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, is a team of health economists, health services and public health researchers, statistical programmers, and policy analysts who engage policymakers to improve Veterans’ lives through evidence-driven innovations using advanced quantitative methods.

The post Using evidence to justify policy and budget decisions first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 24, 2024

Supplement Madness: Magnesium Edition

Only with considerable effort could I find/figure out all that follows. It’s not that hard, but there seems to be a gap in the (easily accessible) internet. This may help fill it.

As a gentle sleep aid, suppose your doctor recommends you take 200 milligrams of magnesium glycinate. Or, suppose you read a recommendation of just that in a newsletter from a well-known neuroscientist. Following this advice is not as simple as you might think.

First, let’s get straight that, putting aside how it is phrased, this is a perfectly reasonable recommendation. Recommended daily allowances of magnesium for anyone other than young kids is in the hundreds of mg; it is quite common that people do not reach these levels through diet; and servings of foods can include many dozens to about 100mg of magnesium. Daily magnesium supplementation up to a 350mg is considered safe for adults, perhaps higher in consultation with a health care provider.

OK, so what are the problems? In short, there two significant communication issues.

The first is that when someone makes such a recommendation (and the internet is full of them), they almost certainly do not mean what it sounds like they mean. When someone says to take “200mg of magnesium glycinate” they really mean “take 200mg of magnesium in the form of magnesium glycinate.” Or, to be even more precise, they mean “take 200mg of elemental magnesium, delivered as a constituent of the compound magnesium glycinate.”

How do I know they mean this? First, there’s what I wrote three paragraphs above. Recommended daily allowances of magnesium are in the hundreds of mg of magnesium not magnesium glycinate (or some other compound of magnesium). As I will explain below, the difference is large. Only by ignorance or sloppiness can one confuse one with the other.

Second, there are many studies that are clear on this point. They examine magnesium for sleep and discuss doses in the hundreds of mg of elemental magnesium, some taken as magnesium glycinate, others as some other magnesium compound (e.g., magnesium citrate, magnesium oxide).

This is an important distinction. Each magnesium glycinate molecule contains one magnesium atom and two glycine molecules (this is why it is also called magnesium biglycinate, the “bi” meaning two). So, the mass of a number of magnesium atoms is less than the same number of magnesium glycinate molecules, by about a factor of 7. Thus, if you follow the advice “take 200mg of magnesium glycinate” literally (meaning you buy and consume as directed a supplement that offers 200mg of the magnesium glycinate compound per serving), you will be taking less than 30mg of elemental magnesium (200/7 is not quite 30). Based on what I’ve already conveyed above, that’s not enough to do anything. You’re way under-dosing.

(If anything about the preceding paragraph is confusing, think of it this way: imagine a special cherry that has as its pit elemental magnesium. Suppose the pit has a mass of 1 (units irrelevant). The pit is surrounded by cherry fruit composed of biglycinate with a mass of 6. The total mass of a cherry, with pit, is 7. Suppose your doctor said you should eat a mass of 210 of these magnesium-pitted cherries (and to eat the pits too, not spit them out), but she really meant that you should eat 210 magnesium pits. If you follow her instructions, you’d eat 30 cherries (210/7 = 30). In doing so, you’d only get 30 mass units of magnesium (30 pits), a far cry from 210!)

OK, so we’re clear that everyone on the internet, in doctor’s offices, and everywhere else should stop saying “take 200mg of magnesium glycinate” and start saying “take 200mg of magnesium in the form of magnesium glycinate” (or something even clearer than that). Good.

Here’s communication issue number two: The supplement market is not adequately regulated. This allows manufacturers to put all kinds of confusing stuff on their labels. This includes:

Not clearly indicating the mg of elemental magnesium, only writing the mg of the compound of which it is a constituent. So, even if you know you want 200mg of elemental magnesium, you’ve got to do some math to figure out how much of this some supplements deliver.Or, providing the mg of elemental magnesium but mislabeling it as that of the compound.Mixing compounds of magnesium — for example, some kind of blend of magnesium glycinate and magnesium oxide — and only providing the mg of this mix. That makes it even harder to figure out how much elemental magnesium is in it (perhaps impossible, because they usually don’t state the ratio of the mix).Sneaky “serving size” bullshit. When the front label says “500mg magnesium glycinate” in big print and “per serving” in small print and the back label says “4 capsules per serving,” that’s some sneaky bullshit. In addition to increasing the risk of taking the wrong dose, it’s another way it makes it very hard to shop, not just on price but also with an eye toward simplifying your pill burden. Nobody wants to take 4 capsules when they could take 2, say (all else equal).There are undoubtedly other tricks and sources of confusion, but these are the ones I easily noticed. The best labels indicate the mg of elemental magnesium and the mg of the full compound of which it is a constituent, per serving. The very best labels consider one capsule a serving.

If all labels were written according to these two “Frakt best practices” magnesium shopping would be far less burdensome. And if all advice-givers were clear about what amount of elemental vs compound-bound magnesium they are talking about, that would reduce confusion.

The post Supplement Madness: Magnesium Edition first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 23, 2024

Supply of Post-discharge Care: A Key to Reducing Hospital Readmissions

Background

The days and weeks after being in the hospital are a vulnerable period, sometimes followed by readmission. High hospital readmission rates in an area can be influenced by factors like socioeconomic status or lack of community support systems. Health system-related failures can also contribute to patient readmission. For instance, gaps in post-discharge care, poor home or nursing home care management, or receiving care at low-quality hospitals can all lead to higher 30-day readmission rates. Ongoing research highlights the importance of addressing social and health system disparities to lower readmission rates.

New research

Evaluators at the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC) and other partner institutions added to this body of literature in a recent paper by investigating the relationship between the local supply of post-discharge care options and hospital readmission rates for patients with acute myocardial infarction (i.e., heart attack), heart failure, or pneumonia.

Study Methods and Limitations

The authors consolidated data (2013-2019) from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the American Hospital Association, the Census Bureau, and the Health Resources and Services Administration. Once condensed, the sample was generally reflective of American hospitals, with over 50,500 hospital-condition-years from over 3,000 unique hospitals included.

Controlling for hospital characteristics, patient demographics, and clinical factors, the authors used multivariable regression models to isolate the impact of local post-discharge care supply on hospital readmission rates. The authors conducted analyses with all three health conditions pooled together as well as with each condition individually.

There were some limitations to the study. For instance, the authors relied on secondary data and could not identify specific reasons why certain post-discharge care options generate more readmissions. Additionally, the data did not differentiate which readmissions were potentially preventable through improved quality of care.

Findings

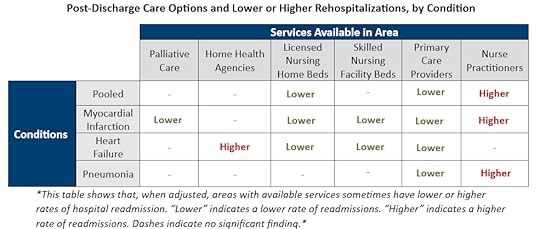

From 2013 to 2019, the population-level availability of post-discharge care options varied greatly by county. When controlling for differences in hospital characteristics, patient demographics, and clinical factors, hospitals in areas with more primary care doctors and nursing home beds had lower readmission rates. Hospitals in areas with greater availability of palliative care and skilled nursing facility beds also had reduced readmissions, though only for individual conditions and not when the three conditions were pooled.

On the other end, hospitals in areas with more available home health agency services saw higher readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Similarly, when conditions are pooled or when analyzing only heart failure or pneumonia, areas with more nurse practitioners are found to have increased readmissions. The authors pointed out that home health agencies experience frequent staffing changes, and areas with higher levels of nurse staffing tend to have greater patient acuity, which may explain these findings.

The figure below represents the findings visually.

Conclusion

After reviewing their findings, the authors argued that improving continuity of care for patients post-discharge would improve patient outcomes. They also proposed that the federal system designed to fine hospitals for high readmissions rates should consider these local health system characteristics to more accurately assign penalties.

Returning to the hospital after recently being discharged isn’t an experience most people want. It’s costly and inefficient. This study speaks to the importance of the availability of post-discharge care services to prevent that experience, offering policymakers a better way forward.

The post Supply of Post-discharge Care: A Key to Reducing Hospital Readmissions first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 10, 2024

Why Do Americans Pay SO Much More for Prescription Drugs?

A fairly large percentage of Americans don’t take important medications as prescribed due to issues of high cost and/or low supply. How did we get here, and what can we do about it? Thanks in part to support from the National Institute for Healthcare Management, that’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

The post Why Do Americans Pay SO Much More for Prescription Drugs? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 9, 2024

Service Dogs vs. Emotional Support Dogs for Veterans With PTSD

Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnoses have increased dramatically for Veterans in the United States. In fact, nearly 400,000 received a diagnosis between 2002–2015.

PTSD is associated with comorbid mental health conditions, decreased functioning and quality of life, unemployment, greater health care costs, and difficulty reintegrating into civilian society. And although antidepressant therapies and trauma-focused psychotherapies may improve PTSD symptoms for some, relief can be elusive for others.

Because PTSD can be a chronic and debilitating condition, combining new treatments with existing treatments may be a valuable strategy. One promising new approach is utilizing service and/or emotional support dogs.

Multiple studies have shown that dogs have beneficial effects on one’s mental health, quality of life, and well-being, especially trained service dogs who can improve PTSD symptoms and social functioning in Veterans. While service dogs are able to perform various tasks specific to assisting a Veteran with PTSD, the sole function of an emotional support dog is to provide comfort (a distinction that disqualifies them from accessing public buildings under the Americans with Disabilities Act).

Studies have yet to assess the therapeutic and economic benefits of service dogs versus emotional support dogs for veterans with PTSD.

New Evidence:

In January 2023, evaluators from the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC) published a novel paper titled “Therapeutic and Economic Benefits of Service Dogs Versus Emotional Support Dogs for Veterans With PTSD” in Psychiatric Services, a journal of the American Psychiatric Association. Authors studied whether providing a service dog versus an emotional support dog to Veterans diagnosed with PTSD improved overall functioning and quality of life over time. Additionally, they assessed PTSD symptoms, suicidal behavior and ideation, depression, sleep quality, anger, and economic outcomes

Methods:

Authors conducted a randomized clinical trial recruiting 181 Veterans diagnosed with PTSD from three Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. The Veterans randomly received either a trained service dog or emotional support dog and were followed for 18 months.

Throughout the study, participants were assessed, either by phone or in person, for several therapeutic outcome measures, including health-related quality of life. They received questionnaires at screening, baseline, before pairing, and at a variety of points post-pairing.

Authors used a linear mixed repeated-measures model to determine changes over time between the service dog and emotional support dog groups. They also used panel models to examine whether treatment assignment was associated with VA health care utilization and costs, with analyses controlled for follow-up time. Work productivity and sensitivity analyses were also conducted.

Findings:

The authors found that both groups appeared to benefit from having a service or emotional support dog, but there were no significant differences in improved functioning or quality of life between the two. Service dogs did not appear to be superior to emotional support dogs in terms of costs, health care utilization, employment, or productivity outcomes. Though, those in the service dog group had a greater reduction in PTSD symptoms, better anti-depressant adherence, and tended to have a reduction in suicidal behavior and ideation compared with those paired with an emotional support dog.

Conclusion:

This study had several limitations. For example, participants were unable to be blind to dog type and there was no control group (i.e., Veterans with no dog) included because that would have created ethical and analytical challenges. The study results may not be generalizable to other populations (e.g., non-Veterans) either.

This study suggests that pairing Veterans with PTSD with service or emotional support dogs can complement existing evidence-based treatments, increase levels of treatment engagement, and reduce PTSD symptoms. Future work should examine the mechanisms by which a service or emotional support dog has an impact on patient functioning, such as by directly reducing PTSD symptoms or by improving treatment engagement or adherence.

PEPReC, within the Veterans Health Administration and funded in large part by the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), is a team of health economists, health services and public health researchers, statistical programmers, and policy analysts who engage policymakers to improve Veterans’ lives through evidence-driven innovations using advanced quantitative methods.

The post Service Dogs vs. Emotional Support Dogs for Veterans With PTSD first appeared on The Incidental Economist.August 28, 2024

How Do Companies Decide Which Drugs to Develop?

Between government funding and pharmaceutical industry spending, billions of dollars are spent annually to bring just a handful of drugs to market. That means some strategic investing is likely going on behind the scenes, and we were curious about the factors driving some of that strategy.

Thanks in part to support from the National Institute for Healthcare Management, that’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

The post How Do Companies Decide Which Drugs to Develop? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.August 19, 2024

How Sleep Deprivation Could Help Heal Depression

Getting enough, good quality sleep every night is important. Yet, hundreds of Americans struggle to get ample rest regularly, despite all efforts. We know sleep deprivation is generally bad for our health, yet research shows it can be harnessed to help heal depression.

About one in three adults report not getting enough sleep, and an estimated 50 to 70 million face chronic sleep disorders. This can lead to sleep deprivation, from either not enough sleep or poor-quality sleep.

The amount of sleep we need changes with age, and we know the consequences of not getting enough. Reaching any point of sleep deprivation can impact daily life, leading to mood changes, difficulty concentrating, and memory issues. Severe and chronic cases can harm connectivity and blood flow in the brain, and result in conditions like heart disease, high blood pressure, and stroke.

The use of sleep aides is at an all-time high, often involving experimenting with different methods to finally get some rest. For those already experiencing sleep deprivation, a recent study found that taking a creatine supplement can improve cognitive performance and energy levels as a way to mitigate the effects of prolonged sleeplessness. This can be useful for those who can’t avoid irregular sleep, such as night shift workers.

Despite the battle for quality sleep and reprieve, some people with depression can actually benefit from sleep deprivation.

Sleep Deprived on Purpose

Wake therapy intentionally uses sleep deprivation to temporarily treat depression. This is because, for some, being in a sleepless state for a prolonged period can boost mood, increase mental and physical stamina, and enhance creativity. What distinguishes wake therapy from other treatments for depression is that it works fast; antidepressants, for example, can take weeks to kick-in.

Triple chronotherapy is one type of wake therapy that uses a combination of one total night of sleep deprivation (33-36 hours), followed by three nights of sleep phase advance (sleep between 6pm and 1am on day one, 8pm and 3am on day two, and 10pm and 5am on day three), accompanied by 30-minute sessions of bright light therapy each morning. This therapy is often given in conjunction with other treatments, like medicine.

It’s been found effective in preventing some from relapsing into depression and shows promise in treating acutely suicidal patients. Despite these findings though, research is still limited and the effects remain short-term.

Manipulating sleep for treatment is tricky since sleep patterns differ for everyone. Our circadian rhythms, or internal clocks, are not consistent and can vary based on genetics, age, sex, exposure to light, and time zone. Because of these complications and other risks, any form of wake therapy should be done under the supervision of a clinician.

Sleep deprivation as a tool for healing isn’t new. Native American communities have long practiced using different forms of deprivation, including lack of sleep, food, or comfort, to access altered states of consciousness. There seems to be something about entering a delirious state of mind that can change the way we process information, and sleep deprivation can be one way to get there. It’s believed that while being in this hypnotic-like state, under the guidance of an elder or shaman, healing of a “lost soul” – otherwise believed to be depression – is possible.

So, does this mean that some of us should purposefully become sleep deprived? Definitely not, as evidence points to the importance of sleep for health and well-being, in general. As for sleep deprivation (wake therapy) to address depression, it is wise to work closely with an experienced practitioner. At the very least, while more research is needed to understand how sleep deprivation can both be avoided and used to address specific conditions, it has shown promise across different communities.

The post How Sleep Deprivation Could Help Heal Depression first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Recent Research: Integrated Health Record Viewers and Duplicate Imaging

In a time when health care providers and patients have hundreds of diagnostic tools at their disposal, containing costs and preventing unnecessary or duplicate testing is crucial.

The United States’ health care spending has grown recently to nearly $5 trillion a year, and some of this spending is due to unnecessary testing.

Unnecessary testing isn’t always the result of an overzealous provider or a worried patient though. It can also occur because of fragmentation and miscommunication between providers and health care systems. Without an ability to connect, fragmentation can increase the risk of adverse health outcomes.

The most common way to connect disparate providers and health systems is through health information exchanges, also known as electronic medical record interfaces. These platforms enable providers to communicate and see prior testing, imaging, and other medical encounters. But, in practice, does provider access to these interfaces actually reduce duplicate testing for Veterans?

Recent Study

Evaluators at the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center set out to answer that question in a study published in JMIR Medical Informatics. The authors sought to estimate the impact of provider usage of the Joint Longitudinal Viewer (JLV) on the ordering of duplicate imaging across the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Department of Defense (DoD).

The JLV is a joint electronic health system utilized by both VA and DoD and allows providers across both enterprises read-only access to their patients’ health records from the other enterprise. For this study, authors examined data from fiscal year 2018 and conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis.

Authors looked at 892 unique medical encounters involving recently separated Veterans with at least one primary care visit at VA within 90 days of an imaging study at DoD. There were a number of exclusionary criteria, such as Veterans who had a primary care visit as part of a compensation and benefits screening or those diagnosed with cancer which may require frequent testing to monitor their illness.

To estimate the relationship between use of the JLV during the primary care visit and duplicate imaging, authors used a logistic regression model. The model controlled for potential confounders, including Veteran age and sex and provider imaging rate in the past six months. To test the results of the model for robustness, evaluators used 2-stage ordinary least squares models and other specifications.

Findings and Limitations

Overall, authors found that JLV use by VA providers increased since fiscal year 2015 when the system was first introduced. Monthly queries in JLV grew to over 1.4 million by 2018.

During this year of peak JLV use, for providers in the study cohort, use of the system was associated with a significant reduction in the likelihood of ordering duplicate imaging. VA providers who did not use the JLV ordered duplicate imaging 11.2% of the time, compared to 6.1% of the time for JLV users.

Additionally, evaluators found differences in duplicate image ordering between providers with historical JLV use and those without. VA primary care providers with a history of using the JLV at least once in the six months before the study period were five percentage points less likely than their counterparts to order duplicate imaging.

However, the authors also acknowledged some study limitations.

First, they only examined primary care visits within 90 days of imaging, so it’s possible that duplicate imaging still occurred, either outside this window or in non-primary care settings.

Secondly, authors noted that they could not delineate between necessary or unnecessary duplicate testing due to data source limitations. Put simply, some seemingly duplicative imaging may have in fact been necessary for monitoring disease. Though authors tried to mitigate this by excluding Veterans with cancer, other conditions may also necessitate frequent testing.

Lastly, authors noted that the results lost robustness with adjustments to the definition of a provider with historical JLV use. According to authors, this suggested “heterogeneity of JLV benefits by frequency of use.”

Takeaway

Study findings suggest that using the JLV and similar longitudinal health information exchanges may reduce duplicate imaging and, therefore, patient burden and unnecessary spending. More research is necessary to understand how electronic medical record features could impact other testing and care in the future.

The post Recent Research: Integrated Health Record Viewers and Duplicate Imaging first appeared on The Incidental Economist.August 18, 2024

Why Do Prescription Drugs Cost SO Much?

In 2020 the expected global expenditure on prescription drugs was somewhere around 1.3 TRILLION dollars, with around $350 BILLION of that spending being done in the United States. The US seems to have a particular issue in this area, with citizens paying much more than their counterparts in similar countries. But why do prescription drugs cost so much? And why do some cost so much more than others?

Special thanks to the NIHCM for supporting this special series on the costs of prescription drugs.

The post Why Do Prescription Drugs Cost SO Much? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.August 14, 2024

The United States’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network: An Overview

While about one third of Americans know someone who has had an organ transplant, the system that organizes the donation and transplantation process remains a mystery to most.

Organ transplantation is a measure of incredible scientific achievement. It began in earnest in the 1950s, with Dr. Joseph Murray performing the world’s first human kidney transplant in Boston. (He later went on to win the Nobel Prize for his work.) The world’s first kidney-pancreas, liver, and heart transplants followed in the late 1960s, along with breakthroughs in immunosuppression in the 1970s, necessary for successful transplantation.

Governing laws

As science advanced, more patients became eligible for transplants, and more donors became available to provide them. But the system matching one to the other was piecemeal.

For decades, a small and scattered group of local transplant hospitals managed organ procurement and transplantation themselves. A national, connected network didn’t exist.

That all changed in 1984 with the passage of the National Organ Transplant Act. The landmark law created today’s Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (the network), a national matching system that fixed a fragmented, inefficient operation.

With the creation of the network, geographically diverse hospitals could communicate with others in the network, making transplantation quicker and more efficient. It also allowed for cross-country transplantation instead of limiting a donated organ to its immediate locale.

Notably, the law also stipulated that only one private organization would be contracted to run the entire network. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) won that federal contract in 1986 and has run the network ever since.

While delegating network operations to one organization seemed efficient at first, UNOS has garnered some valid criticism during its 40-year reign, including complaints about its antiquated technology and operational failures resulting in discarded organs.

A new law passed in 2023 addressed this by breaking up UNOS’ monopoly over the network and allowing the federal government to contract with multiple organizations at once to run it. These contract changes are still in the works.

Registry

The network uses a national registry to match deceased and living donors to recipients. This registry contains important details about both parties, including blood type, body size, and demographics.

When an organ becomes available, algorithms use all of those details to generate a list of eligible recipients, ranked by a composite score. Importantly, recipients aren’t simply ranked based on when they got on the waiting list. Instead, the registry is a “dynamic, ever-changing pool of information.” The organ is then offered to the top eligible recipient on the list and, if declined by the patient’s surgical team, is offered to the next person. (An organ may be declined due to a size mismatch or the recipient being temporarily unsuitable for transplant, among other reasons.)

Procurement and Transplantation

While UNOS oversees the entire national transplantation network, much of the work is coordinated by local organ procurement organizations.

Once a local organ procurement organization learns that an organ is available in its catchment area, it coordinates procurement from the donor and arranges transportation via ambulance, private courier service, or even commercial flight.

While most organs are delivered successfully, some organs are delayed in transit, lose viability, and have to be thrown away. Some just get lost, too.

Once received by the recipient’s surgical team, they work against the clock to transplant the organ. Through special preservation methods, organs can survive outside of the body for varying amounts of time. For example, kidneys can last up to 48 hours, while hearts and lungs can only survive four to six hours.

After surgery, the recipient maintains a lifelong regimen of immunosuppressant drugs and other treatments to prevent their body from rejecting the new organ. The network tracks outcome measures for successful transplantation, including recipient mortality and the transplant organ’s survival and functionality.

Organ donation has seen truly amazing innovation in the last 75 years. The United States’ network alone has saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Even though it is undergoing an operational makeover to improve efficiency and transparency, the network has proven its value and made good on Congress’ 1984 promise to streamline organ donation.

The post The United States’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network: An Overview first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers