Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 106

April 22, 2018

On snoring, 1

You lucky duckies have an opportunity to watch me blog my way through some snoring and sleep apnea literature, though it may put you to sleep. I’m starting with snoring, right here, right now. (These are just quotes and notes. Some readers may recall I used to do this all the time.)

Hoffstein, V., 2007. Review of oral appliances for treatment of sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep and Breathing, 11(1), pp.1-22.

This is a systematic review that covers oral appliance use for snoring or sleep apnea. Since many other reviews focus on the latter, I’m principally using it for the former.

“Treatment of sleep-disordered breathing (i.e. snoring, upper airway resistance syndrome, sleep apnea syndrome) can be divided into four general categories. These include: (1) lifestyle modification, i.e. weight loss, cessation of evening alcohol ingestion, sleep position training, (2) upper airway surgery, (3) oral appliances, and (4) CPAP.”

Not enough dentists are familiar with the treatment of sleep-disordered breathing with oral appliances. “Bian [7] surveyed 500 general dentists in the state of Indiana and found that 40% ‘knew little or nothing about oral appliances for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea’. Caution: This publication is 14 years old.

“George Cattlin [8] [published 1861] was probably the first person who seriously thought that the route of breathing may influence sleep quality and daytime function. He attributed good health of the native North American Indians, compared to their immigrant European counterparts, to the fact that they are taught, from the early age, to breathe through the nose rather than the mouth. He pointed out that breathing through the nose promotes more restful and better quality sleep, which translates into better daytime function and better general health.”

Snoring and sleep apnea are on the same continuum, both due to obstruction (either partial or complete, respectively) of the upper airway.

Oral appliances were invented to treat snoring. My comment: Good ones aren’t cheap (in the four figures) and insurance won’t cover them for snoring, only sleep apnea. Since they’re made to fit, you can’t resell or return one if it doesn’t work. This makes it a challenging decision to try an oral appliance to address snoring.

“In some patients with sleep apnea these alterations [made by mandibular advancement devices] may prevent the obstruction, in others—worsen the obstruction, and yet in others, particularly in those with low level obstruction, the part of the airway where the obstruction occurs may be unaffected.” Comment: I don’t approve of this particular use of the em-dash.

“We note that the findings of all such studies are remarkably consistent—CPAP results in better improvement in AHI than oral appliances. […] However, patients subjectively prefer oral appliances over CPAP.”

There are lots of kinds of oral appliances. “There is no ‘best’ appliance. The best one is that which is comfortable to the patient and achieves the desired efficacy.”

This is my favorite part (emphasis added): “However, snoring is the cardinal symptom of sleep apnea. In fact, it is frequently the only reason why these patients come to the sleep clinic in the first place. Consequently, when polysomnography does not reveal sleep apnea in these patients, the physician still has to deal with their snoring. Unfortunately, this is often ignored by physicians. The most frequent scenario is that a patient is referred to a sleep specialist because of snoring, polysomnography is carried out, no sleep apnea is found, the patient is reassured, advised to loose weight, stop smoking and drinking alcohol, embark on an exercise program, and discharged from the clinic. Sometimes this advice, dispensed in the form of preprinted sheets, is given also to non-obese nonsmokers. Clearly, the patient leaves unhappy, the referring physician is dissatisfied with the help received from the specialist and nothing was accomplished to justify the

expense incurred in the process of investigations. For apneic snorers, the problem is simpler because treatment with CPAP will abolish snoring.” Comment: Not sure we need to justify sunk costs. But it would be better to help the patient. But, as mentioned above, it’s not such a simple matter when insurance doesn’t cover oral appliances (or anything) for snoring.

“the majority of the investigations concluded that oral appliances are beneficial in reducing snoring in the majority of patients.”

“the conclusion from all of the investigations taken as a group must be that oral appliances improve daytime

function, although they are not necessarily superior or consistently preferred than other treatments such as CPAP and UPPP.”

“There is not enough evidence at the present time to draw any conclusions regarding the effect of oral appliance therapy on vascular disease.”

Oral appliance side effects: excessive salivation, mouth, and teeth discomfort. “The conclusion, based on the results of most studies, is that when oral appliances are properly constructed by the dentist with expertise in this area, they are relatively comfortable in the majority of patients.”

Between 36% and 70% of patients are not compliant with oral appliances. Reasons for discontinuation include discomfort or perception of no benefit. However, if one is using an OA to address snoring that bothers a sleep partner, but that sleep partner is no longer bothered by it (or present for it), then use might be discontinued with no problematic clinical outcomes.

“The evidence available at present indicates that oral appliances successfully ‘cure’ mild-to-moderate sleep apnea in 40–50% of patients, and significantly improve it in additional 10–20%. They reduce, but do not eliminate snoring. Side effects are common, but are relatively minor. Provided that the appliances are constructed by qualified dentists, 50–70% of patients continue to use them for several years.”

April 21, 2018

Uwe Reinhardt’s memorial service

It was today at Princeton University. I learned a lot from the speakers and the biography in the program. I thought those who couldn’t attend might like to see the latter. Among other things, it conveyed just how hard Uwe worked (and had to work) as a youngster and to obtain his education.

In the postwar years, the Reinhardt family (Uwe’s mother, grandmother, and his four siblings) lived in a rural toolshed without electricity or water and often went hungry. Heavy physical work started at a young age out of necessity, and economic deprivation instilled discipline and work ethic; laughter, singing, and his mother reading to the children by candlelight were constants of family life. Uwe always said he had the best and happiest childhood in the world. […]

After three years of working two jobs (the second job parking cars at night), Uwe had saved enough money to go to the “cheapest” university in Canada — the University of Saskatchewan — graduating as the winner of the Governor’s Gold Medal (valedictorian).

The rest is in pictures, below. Click to enlarge.

Provent tips

I imagine there may be people searching for the answers to questions about Provent sleep apnea therapy that I had a few days ago. I couldn’t find the answers on the internet, so having figured them out for myself, perhaps I can save others some time and aggravation.

Q: I can’t breathe with these things. I wake up feeling like I’m suffocating. Aren’t there lower resistance versions?

A: Apart from the few nights of training patches included in the start-up kit, not that I’ve found. But, you can turn the standard resistance Provent patches into lower resistance ones by peeling a small section of each patch off your nose. I’ve done this for several nights in a row now, sleeping well. I suppose one could consider widening the hole in the valve (maybe with a drill bit?) but I haven’t bothered. An advantage to my approach is that I find that there are portions of then night during which I can tolerate higher resistance. During those, I press more of the patch on. Other portions, I peel more away, but in all cases leaving enough on to feel some resistance.

Q: These are expensive. Any way to reduce the cost?

A: Yep. You can use each pair of Provent patches for more than one night. I’ve easily gotten two nights out of a pair, by peeling them off carefully in the morning and returning them to the backing paper. I would bet there will be occasions when I could even get three nights. I suppose if one could find the right liquid adhesive (safe for skin), one could reuse a pair for many nights.

Q: Why doesn’t anyone discuss these issues on the internet?

A: I can only guess. Though many may try Provent, I suspect very few people actually get through more than a few nights before giving up. Of those that do, some are fine with it as is. Some of those struggling aren’t the type to hit the web with questions/answers. It ends up a niche product, and the sleep apnea forums are overwhelmed with CPAP Q&A. It’s too bad, because Provent can be very useful, yet challenging. Hopefully this post is of some help to others.

April 20, 2018

Just how many billions of dollars are at stake in the litigation over cost-sharing payments?

Earlier this week, the Court of Federal Claims certified a class action brought by insurers to recover the cost-sharing payments that President Trump unceremoniously terminated. At first blush, the court’s opinion looks unremarkable. Because insurers share a common legal claim—you promised to pay me, and you broke that promise—it makes sense to certify a single class instead of dealing with a bunch of duplicative lawsuits.

But the rationale the court employed to reach that result is potentially explosive. Should it stand up on appeal, it suggests that the federal government will be liable for tens of billions of dollars in damages, with the precise amount growing every day. It’s worth explaining why.

* * *

If insurers win these lawsuits—and they should—how much money will they get? Can they recover all of the cost-sharing payments that the ACA promises to them? Or have insurers mitigated their losses by hiking the premiums for their silver plans and shifting unsubsidized enrollees to gold or bronze plans—a practice known as “silver loading”?

Back in December, I explained the role that mitigation would play in the cost-sharing litigation:

[Mitigation is] a principle that might be familiar to you if you’ve ever thought about breaking a lease on an apartment. Although your landlord can sue you for any rent owed for the months remaining on the lease, he also has a duty to find a new tenant. If he does, you only have to compensate your landlord for the time that the apartment was empty. The landlord has mitigated his losses.

The same principle should kick in here. Silver loading has allowed insurers to sidestep most of the harm associated with the loss of the cost-sharing subsidies. Insurers haven’t hemorrhaged customers; instead, they’ve adapted. Indeed, some insurers are better off now than they were before: as premium subsidies increase, they’ll get more customers signing up for their gold and bronze plans.

I also explained, however, that it was the government’s responsibility to prove that insurers had in fact mitigated their damages, and that “the factual inquiries will be demanding. … It’s hard to know what the world would have looked like if the cost-sharing payments had been made, so it’s hard to know whether any given insurer is better off or worse off now that they’ve been terminated.”

In fighting over class certification, the government latched onto this point—the complexity of the factual inquiry over damages—to argue that class certification was inappropriate. Each individual insurer’s damages will be different, the government argued, so it’d be madness to try to resolve their claims in a single suit.

The judge didn’t buy it:

[The government] does not identify any statutory provision permitting [it] to use premium tax credit payments to offset its cost-sharing reduction payment obligations (even if insurers intentionally increased premiums to obtain larger premium tax credit payments to make up for lost cost-sharing reduction payments). In the absence of such an offset, the calculation of each potential class member’s unpaid cost-sharing reduction payments appears to be a rather straightforward process based on data provided to the government by the insurers—the identity of each qualified health plan in which individuals eligible for cost-sharing reductions are enrolled, and the amount of each individual’s cost-sharing reduction. Such a calculation lacks the complexity that would overwhelm the issues common to the proposed class.

In other words, mitigation is irrelevant to the ultimate damages calculation. Insurers are instead entitled to every dollar that they’re owed under the ACA’s statutory formula.

* * *

The court’s refusal to consider mitigation will make no difference for the $2 billion or so that’s due to insurers for the cost-sharing payments they lost in 2017. But it could matter enormously for the many billions in cost-sharing payments that insurers are entitled to in 2018. The same goes for 2019, 2020, 2021 … you get the point. Every day that the ACA’s cost-sharing provisions stay on the books is another day of additional liability. As Dave Anderson noted this morning, “[t]he net present value under dispute for the next decade could easily reach $100 billion dollars.”

Congress could stop the bleeding by wiping out the statutory obligation to make cost-sharing payments. Indeed, the judge’s decision will put pressure on Congress to do just that. But Democrats and Republicans are at loggerheads over what to do with the cost-sharing payments, and I don’t see matters improving after the midterms. The bleeding will likely continue.

* * *

What happens next? If it gets permission from the Federal Circuit, the government can immediately appeal the decision to certify the class. Given the stakes, I suspect both that the government will seek permission and that the Federal Circuit will grant it. On appeal, the government will raise the argument about mitigation; if it loses there, it could take the question to the Supreme Court.

I don’t know if the court’s rationale will be upheld on appeal. I’ll admit, however, to some skepticism. The judge found it significant that no statute allows the government to offset its cost-sharing liabilities. Why should that matter, though? Damages calculations in the Court of Federal Claims are governed by federal common law, and federal common law requires an inquiry into mitigation, even in cases against the United States. Nothing in the ACA purports to disturb that general rule.

Now, the decision to certify a class might still be defensible. The judge offered an alternative basis for judgment: “it is well settled that the need for individualized damages calculations does not preclude the certification of a class.” Although that statement strikes me as too categorical to be universally true—in some cases, won’t damages questions be so tricky that class certification would be inefficient?—it’s at least a close question.

On the ultimate question of damages, however, this case is by no means over. I still think that insurers shouldn’t be too bullish about recovering cost-sharing money for 2018 and beyond. But they’re one big step closer to that goal.

April 19, 2018

Healthcare Triage News: Ketamine Can Be a Fast-Acting Antidepressant

A recent study looked into ketamine, noted animal sedative and party depressant, as a short-term treatment for severe, emergency room level depression. While it can help people who are suffering from suicidal ideation, it is a short term treatment. Also, approving the drug would mean more accessible (and more easily abused) ketamine.

Understanding billing complexity for physician care in the US

Elsa Pearson is a Policy Analyst with Boston University’s School of Public Health. She tweets at @epearsonbusph. Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

In general, the research literature on administrative costs, which I summarized in a prior TIE post, assesses three broad categories: billing and insurance-related costs, hospital administrative costs, and physician practice administrative costs. But, there has been little comparison of administrative costs across insurance types…until now.

As promised in that post, below is a review of the recent Gottlieb, Shapiro, and Dunn Health Affairs article that fills that gap in the literature. Gottlieb et al. focus on the differences in billing complexity across insurers. They use billing complexity as an indicator of the burden of total health care administrative costs within the US system.

Methods

The authors used 2013-2015 claims data from the IQVIA Real-World Data Adjudicated Claims. IQVIA collects claims data for all the payers with whom a sample of physicians contract or bill, allowing researchers to study differences across payers for the same provider. Gottlieb et al. principally analyzed a sample of 68,000 physicians in the 2015 IQVIA data, though also looked at trends in some measures from 2013-2015. They considered five insurance types: fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare, Medicare Advantage, FFS Medicaid, Medicaid Managed Care, and private.

The authors characterized billing complexity in multiple ways. One set of measures pertains to how much of each claim was never paid: amount challenged and share challenged. Amount challenged was defined as the difference between what was actually paid for services and the full negotiated price. Share challenged was defined as the fraction of the negotiated price that was never paid. The authors understand that challenged claims are not equivalent to total administrative costs but believe they are a strong indication of national cost trends.

In addition to these measures of challenged claims, they used another four complexity measures: time to payment, number of interactions between physician and payer, claim denial, and nonpayment.

The authors use these measures to characterize billing complexity in the following sense: challenging and denying claims, as well as additional interactions between physician and payer, requires work (and resources) from both parties. Effectively, billing complexity means that additional resources are ultimately required for each dollar paid.

Comparisons of measures across insurance types were conducted using physician-specific fixed effects and adjusting for the logarithm of the allowed charge, the number of claims, each patient’s Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and each patient’s age. This limited the impact of differing patient populations.

Results

The analysis included 37.2 million office visits, totaling 44.5 million insurance claims. FFS Medicare and private insurance each accounted for almost 40% of the claim data and included more lengthy claims due to more complex clinic visits.

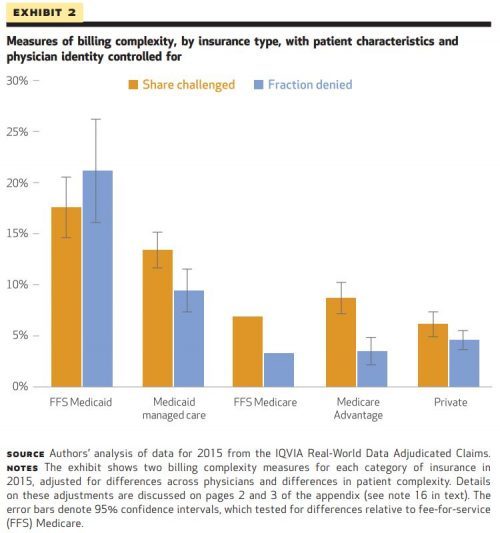

Overall, the authors found Medicaid, both FFS and Managed Care, to be the most complex insurer across all measures. Both types of Medicaid had the highest shares challenged (21% and 13%, respectively) as well as the longest times to payment. Medicaid claims were also denied three times as much as Medicare claims. (Of note, given lower overall potential payments, the monetary value of Medicaid shares challenged was comparable to other insurance types.)

The authors found billing complexity to be notable regardless of insurance type (for example, private insurers still had a share challenged of 6%) though the variation between insurers was substantial. Exhibit 2 shows this variation.

Finally, Gottlieb et al. extrapolated national estimates of contested claims. They calculated that the US health care sector handles up to $54 billion in challenged claims a year (though this estimate may be on the high end).

Limitations

As with any study, there are a few limitations. The authors note that the data are limited to only the physicians who participated in IQVIA’s collection process. Further still, the data do not adequately capture the breadth of insurance administration. For example, the data do not contain costs associated with prior authorizations, actuarial services, or marketing.

Impact

Since billing complexity varies across payers, reducing billing complexity is possible. (In other words, if FFS Medicare can have lower billing complexity than FFS Medicaid, perhaps there is room for improvement in FFS Medicaid billing practices.)

Reducing the administrative headache and wasted financial resources associated with billing practices may cause some providers to be more willing to accept patients with public insurance. Providers could also reclaim time and resources spent on administrative activities for patient care, increasing productivity.

The authors suggest a better understanding of administrative costs could also impact health policy, particularly antitrust policy and merger evaluation. Insurers and providers alike could weigh billing complexity when considering payment contracts, pursuing contracts based on administrative burden. Because of this, governing leadership could start to consider these types of nonmonetary aspects of insurer/provider relationships when assessing proposed mergers.

Gottlieb, Shapiro, and Dunn offer a fresh perspective on US health care administrative costs through their analysis of billing complexity. There seems to be some promise that billing complexity—and its associated costs—could be reduced across payers. In a health care system wrought with expense, it’s encouraging to see room for even small improvements.

April 18, 2018

We Know How Poverty Hurts Children. It’s Time to Intervene.

This piece is authored by Tonya Pavlenko, a Research Analyst at Center on Poverty and Social Policy (CPSP) at Columbia University.

In the last year I’ve sat across from several hundred expectant mothers who are living in poverty. I meet them in overcrowded apartments, drafty shelter rooms, or the public library if things are too unstable at home. Over the course of an hour I ask them a series of very personal questions about their health, their financial and employment history, their relationships, and hopes for their baby’s future. I’m there to gather data for an evaluation of a poverty intervention program called Room to Grow, a program that aims to give expectant mothers the supports they need to help them and their newborns thrive. The program couples parenting supports from clinical social workers with valuable material goods that make parenting easier – think diapers, clothes, books, strollers, and the like. This is the beginning of a randomized controlled trial where we will study the impacts of the intervention, comparing mothers and babies who receive services from Room to Grow and those who do not—with the goal of being able to measure the capacity of this intervention to alleviate the symptoms of poverty for some of New York City’s most vulnerable mothers.

When I first began studying poverty I started with a common assumption—that it’s a relatively stagnant condition. The poor remain poor and the cycle of poverty endlessly churns across new generations. While this situation is true for many, the assumption of a fixed poor population is too reductive. The latest research demonstrates the transience and reach of poverty: 46% of New Yorkers have experienced poverty for at least one year. In 2013, 9% of New Yorkers remained poor across two consecutive years, while equal numbers entered or exited a spell of poverty in just one of those years. The implication is clear: poverty is movable, and interventions can help people escape.

Though we typically think of things like job loss or a pay cut as precursors to poverty, a surprisingly common trigger is the birth of a new baby. Consider Cara Williams. At 23, she is engaged and pregnant with her first child. On my way to meet Cara I take two subway lines and a bus, then walk 20 minutes through the blustering cold—the apartment she shares with her brother and cousin is on the outskirts of Brooklyn. While I walk I realize that this is part of her commute every day; to make rent in a city with some of the most expensive housing, she has been pushed to the outskirts. Loose trash blows at my feet; I notice a frayed wire hanging down the side of her apartment building, the cord precariously caught in some rusted window guards. There’s a buzzer system, but it doesn’t work—the steel door requires a mere shove and I’m inside a lobby that reeks of urine and mildew. A few people shuffle past, they look weary; they know I don’t live here, but give a friendly nod and hold the elevator door.

Cara greets me—her belly swollen, eyes tired—and guides me to the bedroom she shares with her cousin. It’s cramped. Everything is always cramped; often poverty is clutter in the midst of scarcity. There are two twin mattresses, separated by a night stand that has a careful arrangement of peanut butter jars, ramen noodle cups, and prenatal vitamins. Tacked above her bed is a print out of a sonogram next to a photo of her fiancé.

After graduating from high school, she had been working at a department store and taking some classes towards an Associate’s degree. Things were going well, her supervisor liked her and hinted about an upcoming promotion to a management position. When her first bouts of extreme morning sickness hit, however, Cara was forced to take time off from work. Unable to keep any food down, she was either at home suffering from weakness and dehydration, or at work running to the bathroom. It did not take long for her secret to come out. Instead of congratulations, however, the news of her pregnancy quickly replaced the potential for a promotion with a pat on the back and the understanding that she would be gone soon, with no maternity benefits and no guarantee of employment after the birth of her baby.

Cara had planned to work up until the ninth month of her pregnancy so that she could save as much as she could for herself and her child. Her doctor insisted, however, that she go on bedrest or risk a premature delivery. Like almost any expectant mother, Cara did what was best for her baby and followed the doctor’s orders. With each hour of bedrest, she noted the $11.50 less she’d have for diapers, books, and baby food.

With her food stamp benefit as her only income since leaving work, she now officially lives in poverty. And what is particularly harrowing about the poverty that follows birth is that there is no shortage of scientific data on the profound impact of poverty on child health and development. Studies have linked poverty during birth and infancy to impeded cognitive development in childhood as well as lower educational attainment and lower earnings later in life. The physical manifestations of poverty are also rampant—poverty is associated with a myriad of health conditions, including: low birth weight, premature birth, higher rates of morbidity and mortality, and chronic illness.

I’ve come to see that what’s needed is not more research into the problem, but research into solutions; rigorous measurements and analyses on what works to lift impoverished families out of poverty and what can prevent the most vulnerable from entering into poverty in the first place. What can funders and policymakers get behind; what trails can America start to blaze with social innovation?

Assistance programs for vulnerable families almost exclusively separate monetary support from social support. For example, many hospitals and nonprofits will offer parenting and prenatal classes for underserved mothers, but then send their clients home without the needed resources to put the lessons into practice. You can teach an expectant mother that reading aloud to her baby is crucial for cognitive development, but that lesson does not address the fact that the food stamps she receives—her only income while she’s been laid off from her part-time job for being pregnant—do not pay for a stack of baby books; they barely even pay for the food she needs to survive. On the flipside, once-a-year income-support policies like the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) offer sporadic cash to families without any social support to back it up. While families should have autonomy over their cash expenditures, social and therapeutic support can help parents take advantage of reduced financial distress in order to better advocate for themselves’ and their children’s needs.

Though the impact of tax credits and parenting programs for disadvantaged moms are well known, there is a major gap in understanding the short and long-term impacts of interventions that fuse financial support with parenting supports. This is why I find a program like Room to Grow so compelling. Mothers in the Room to Grow program form a relationship with a clinician—a social worker who meets with them every three months and stays in contact over the course of three years. During in-person visits, mothers like Cara work with their clinician to set goals, work through obstacles, and learn about their child’s needs and developmental milestones. At each visit, mothers also receive concrete material goods that help meet their needs for the particular phase of their baby’s development—over the course of 3 years, she receives $10,000 worth of in-kind support.

As I wrap up the interview with Cara, I ask her a final few questions about hopes she has for her baby’s future. She smiles: “I want him to know he is loved. And in life…I want him to achieve the things I just didn’t have a chance to,” she says. While the stories I hear are different, the answers to the last few questions rarely stray from these sentiments. I thank Cara and give her a hug before I leave. The next time I’ll talk to her is when her baby is 10 months old for the first round of study follow-up. By that time her son will be learning his first words and pulling himself up to stand; absent innovative programs like Room to Grow, it’s likely his first steps will be in the narrow space between two twin mattresses.

Under the direction of Chris Wimer and in partnership with Room to Grow, the Center on Poverty and Social Policy is currently conducting a randomized controlled trial of the Room to Grow program, an innovative poverty intervention that supports mothers and babies in the first three years of life.

Would Americans Accept Putting Health Care on a Budget?

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2018, The New York Times Company).

If you wanted to get control of your household spending, you’d set a budget and spend no more than it allowed. You might wonder why we don’t just do the same for spending on American health care.

Though government budgets are different from household budgets, the idea of putting a firm limit on health care spending is far from unknown. Many countries, including Canada, Switzerland and Britain, pay hospitals entirely or partly this way.

Under such a capped system, called global budgeting, a hospital has an incentive to deliver less care — including reducing hospital admissions — and to increase the efficiency of the care it does deliver.

Capping hospital spending raises concerns about harming quality and access. On these grounds, hospital executives and patient advocates might strongly resist spending constraints in the United States.

And yet some American hospitals and health systems already operate this way, including Kaiser Permanente and the Veterans Health Administration. To address concerns about access and quality, these programs are usually paired with quality monitoring and improvement initiatives.

That brings us to Maryland’s experience with a capped system. The evidence from the state is far from conclusive, but this is a weighty and much-watched experiment for health researchers, so it’s worth diving into the details of the latest studies.

Starting in 2010 with eight rural hospitals, and expanding its plan in 2014 to the state’s other hospitals, Maryland set global budgets for hospital inpatient and outpatient services, as well as emergency department care. Each hospital’s budget is based on its past revenue and encompasses all payers for care, including Medicare, Medicaid and commercial market insurance. Budgets for hospitals are updated every year to ensure that their spending grows more slowly than the state’s economy.

Because physician services are not part of the budgets, there is an incentive to provide more physician office visits, including primary care. According to some reports, Maryland hospitals are responding to this incentive by providing additional support outside their walls to patients who have chronic illnesses or who have recently been discharged from a hospital. Greater use of primary care by such patients, for example, could reduce the need for future hospital admissions.

n 2013, early results found, rural hospital admissions and readmissions were both down from their levels before the system was introduced.

In the first three years of the expanded program, revenue growth for Maryland’s hospitals stayed below the state-set cap of 3.58 percent, saving Medicare $586 million. Spending was lower on hospital outpatient services, including visits to the emergency department that do not lead to hospital admissions. In addition, preventable health conditions and mortality fell.

According to a new report from RTI, a nonprofit research organization, Maryland’s program did not reap savings for the privately insured population (even though inpatient admissions fell for that group). However, the study corroborated the impressive Medicare savings, driven by a drop in hospital admissions. In reaching these findings, the study compared Maryland’s hospitals with analogous ones in other states, which served as stand-ins for what would have happened to Maryland hospitals had global budgeting not been introduced.

But a recent study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, was decidedly less encouraging.

Led by Eric Roberts, a health economist with the University of Pittsburgh, the study examined how Maryland achieved its Medicare savings, using data from 2009-2015. Like RTI’s report, it also compared Maryland hospitals’ experience with that of comparable hospitals elsewhere.

However, unlike the RTI report, Mr. Roberts’s study did not find consistent evidence that changes in hospital use in Maryland could be attributed to global budgeting. His study also examined primary care use. Here, too, it did not find consistent evidence that Maryland differed from elsewhere. Because of the challenges of matching Maryland hospitals to others outside of the state for comparison, the authors took several statistical approaches in reaching their findings. With some approaches, the changes observed in Maryland were comparable to those in other states, raising uncertainty about their cause.

A separate study by the same authors published in Health Affairs analyzed the earlier global budget program for Maryland’s rural hospitals. They were able to use other Maryland hospitals as controls. Still, after three years, they did not find an impact of the program on hospital use or spending.

Changes brought about by the Affordable Care Act, which also passed in 2010, coincide with Maryland’s hospital payment reforms. The A.C.A. included many provisions aimed at reducing spending, and those changes could have led to hospital use and spending in other states on par with those seen in Maryland.

A limitation of Maryland’s approach is that payments to physicians are not included in its global budgets. “Maryland didn’t put the state’s health system on a budget — it only put hospitals on a budget,” said Ateev Mehrotra, the study’s senior author and an associate professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School. “Slowing health care spending and fostering better coordination requires including physicians who make the day-to-day decisions about how care is delivered.”

A broader global budget program for Maryland is in the works. The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is reviewing a state application that commits to global budgets for Medicare physician and hospital spending. An editorial that accompanied the JAMA Internal Medicine study noted that a few years may be insufficient time to detect changes. It suggests that five to 10 years may be more appropriate.

“Maryland hospitals are only beginning to capitalize on the model’s incentives to transform care in their communities,” said Joshua Sharfstein, a co-author of the editorial and a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “This means that as Maryland moves forward with new stages of innovation, there is a great deal more potential upside.” As former secretary of health and mental hygiene in Maryland, he helped institute the Maryland hospital payment approach.

Global budgets are unusual in the United States, but their intuitive appeal is growing. A California bill is calling for a commission that would set a global budget for the state. And soon Maryland won’t be the only state using such a system. Pennsylvania is planning a similar program for its rural hospitals.

Can this system work across America?

How much spending control is ceded to the government is the major battle line in health care politics. An approach like Maryland’s doesn’t just poke a toe over that line, it leaps miles beyond it.

But the United States has been trying to get a handle on health care costs for decades, spending far more than other advanced nations without necessarily getting better outcomes. A successful Maryland experiment could open an avenue to cut costs through the states, perhaps one state at a time, bypassing the steep political hurdle of selling a national plan.

April 17, 2018

Sleep hacking

Almost exactly two years ago, I experienced symptoms of sleep apnea. It lasted a couple nights, then disappeared until late December 2017. Naturally, I suspected nothing at the time, it being a one-off. In hindsight, it suggests my condition is not a few months old, but a couple of years.

It is indeed possible, according to the sleep expert in Calgary with whom I’ve corresponded. Sleep apnea can begin in mild, even intermittent form and gradually worsen over time, as one ages.

That’s a reasonable theory for my case. If true, it means my body has had a couple years to get good at responding to breathing difficulty during sleep. When my airway is blocked, it now rouses me, quite expertly, to consciousness if my sleep isn’t deep enough.

But, does it matter exactly how my airway is blocked? I don’t see why. My sleeping brain should react with the same panic.

Well, guess what? Provent therapy, which I’ve mentioned before works by restricting the airway on exhalation only. The point of this is to increase internal pressure that keeps the airway open. It does so with carefully crafted valves one applies to the nostrils with adhesive patches. They allow inhalation with little resistance, but exhalation is highly restricted. It’s ingenious, and there is evidence it can be effective for obstructive sleep apnea. See this systematic review and meta analysis.

The starter kit comes with two nights each of low and medium resistance patches, to help get used to the more extreme, therapeutic level patches. According to feedback from my wife, those worked pretty well for me. For the first time in years, I didn’t snore, she said. That’s by no means scientific evidence of reduction in apnea events, but it is consistent with it.

However, the standard, therapeutic level resistance is, to my taste, extremely restrictive. Except when I’m in deep (and, to date, Ambien-aided) sleep, my subconscious brain reacts the same way as to an apnea event. It wakes me up, and does so to consciousness more often than I’d like. Maybe one can get used to this. But it is darn hard to train one’s subconscious mind to relax and not panic during breathing restrictions.

Sleep hacking is hard … because you’re asleep!

So, it seems, at least until I get a more effective treatment (next week) I can choose my poison: wake up to apnea events (without Provent) or wake up to self-inflicted exhalation resistance (with Provent). Not much of a choice.

But there’s a third option. I can intentionally degrade Provent’s resistance by introducing some air gaps that partially bypass the device—basically trying to mimic the low-to-medium level resistance with the high resistance patches I have left. (I haven’t seen lower level resistance patches on the market. Anyway these things are expensive, so I’m not sure I’d buy them, having already invested in the starter kit that comes with ~30 pairs of standard resistance ones.)

Maybe I can find a balance between raising airway pressure enough to reduce apnea events, but not enough that my brain panics. I crudely experimented with this last night, but it was not a great test. More to come.

This is another way sleep hacking is hard. You can only experiment during the same type of sleep you’re having trouble with. That may only happen a few hours per night. There’s no way to speed up the cycle of innovation.

The Role of Pediatricians in Reproductive Health Advocacy

Tracey Wilkinson (superstar faculty at IUSM) and I have a Viewpoint just out in JAMA Pediatrics:

Reproductive health advocacy has become more essential than ever before. Despite the United States having one of the highest rates of teen pregnancy among developed countries, general discomfort and unfamiliarity still persist among pediatricians regarding pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection prevention as well as provision of contraception. That attitude must change.

Go read it!!!

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers