Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 103

May 10, 2018

It’s Time for a New Discussion of Marijuana’s Risks

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2018, The New York Times Company).

The benefits and harms of medical marijuana can be debated, but more states are legalizing pot, even for recreational use. A new evaluation of marijuana’s risks is overdue.

Last year, the National Academies of Sciences, Medicine and Engineering released a comprehensive report on cannabis use. At almost 400 pages long, it reviewed both potential benefits and harms. Let’s focus on the harms.

Cancer

The greatest concern with tobacco smoking is cancer, so it’s reasonable to start there with pot smoking. A 2005 systematic review in the International Journal of Cancer pooled the results of six case-control studies. No association was found between smoking marijuana and lung cancer. Another 2015 systematic review pooled nine case-control studies and could find no link to head and neck cancers.

Another meta-analysis of three case-control studies of testicular cancer found a statistically significant link between heavier pot smoking and one type of testicular cancer. But this evidence was judged to be “limited” because of limitations in the research (all of which was from the 1990s).

There’s no evidence, or not enough to say, of a link between pot use and esophageal cancer, prostate cancer, cervical cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, penile cancer or bladder cancer. There’s also no evidence, or not enough to say, that pot has any effect on sperm or eggs that could increase the risk of cancer in any children of pot smokers. (Using marijuana while pregnant does pose other risks, as discussed below.)

Heart disease

Another major risk with cigarettes, heart disease, isn’t clearly seen with pot smoking. Only two studies quantified the risk between marijuana use and heart attacks. One found no relationship at all, and the other found that pot smoking may be a trigger for a heart attack in the hour after smoking. But this finding was based on nine patients, and may not be generalizable.

Lung function

It also makes sense to think about the risk of respiratory disease. In the short term after smoking pot, a 2007 systematic review found, lung function actually improved. But these benefits were completely overtaken by evidence that lung function may degrade with chronic use. Lung function, however, is a laboratory measure and not necessarily a clinical outcome, and what we really care about is lung disease. Once you control for tobacco use, the links between marijuana and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease appear minimal. Almost no evidence is available to link pot use to asthma.

Impaired driving

Driving while impaired is a major cause of injury and death in the United States. Six systematic reviews were considered of fair or good quality by the national academies, and the most recent one pooled three of the others. It contained evidence from 21 studies in 13 countries representing almost 240,000 participants.

For people who reported marijuana use, or had THC detected through testing, their odds of being involved in a motor vehicle accident increased by 20 to 30 percent, the study found. This is, of course, a relative increase, and shouldn’t be confused with the overall percentage chance of getting in an accident, which is much smaller.

Regardless, driving while impaired is a terrible idea. Although we have good tests to determine if people are under the influence of alcohol, no such tests are currently available for marijuana, making enforcement more difficult.

Pregnancy effects

Babies born to women who smoke pot during pregnancy are more likely to be underweight, delivered premature and admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit, according to a 2016 systematic review. But there were no links seen for changes in birth length, head circumference or congenital malformations. There’s limited evidence for pregnancy complications for mothers, and there’s not enough evidence to comment on much else about babies and their outcomes.

Memory and concentration

There’s moderate evidence, from many studies, that learning, memory and attention can be impaired in the 24 hours after marijuana use. There’s limited evidence, however, that this translates into worse outcomes in academic achievement, employment, income or social functioning, or that these effects linger after the pot has “worn off.”

Mental health

The possible relationship between marijuana use and mental health is complicated. The most recent meta-analysis found that there’s a significant connection between heavy marijuana use and a diagnosis of psychosis, specifically schizophrenia. This mirrored the findings of previous reviews that sought to cover only high-quality studies. Another systematic review highlighted a potentially small but statistically significant link between marijuana use and the development of bipolar disorder. Heavy users of pot are also more likely to say they have suicidal thoughts.

What makes this complicated is that it’s hard to establish the arrow of causality. Are people who smoke pot more likely to develop mental health problems? Or are people with mental health problems more likely to smoke pot?

There’s a similar issue when talking about the relationship between using pot and other substances. Some see marijuana as a “gateway” drug, leading to other substance use or abuse. Others see this as only a correlation in which people who are likely to use or abuse substances are more likely to use pot as well.

Secondhand smoke

As states legalize the drug for general use, more cannabis users feel freed from secrecy. They smoke more in public, raising worries about secondhand smoke. A two-year-old study made news recently by arguing that one minute of exposure to pot smoke impaired how vessels responded to blood flow for at least 90 minutes, a greater impairment than from tobacco. This was a study in rats, though, not of humans out in the world. As for risk of a “contact high,” the amount of THC detectable in secondhand smoke is negligible.

Almost all agree that children should not use pot, but concerns are legitimately raised about whether children might have increased exposure or access after legalization. Although this issue has not been studied widely, it’s possible that pot — the THC and the metabolites from smoke — could have an effect on the developing brains of children. These concerns are more applicable to adolescents who use pot regularly, however, not the accidental ingestion reported in the news once in a while.

New questions

Almost all the harms the medical literature focuses on involve smoked cannabis. We know little to nothing about edibles and other means of administration. Nor do we have any consistent manner of measuring the level of exposure.

Bottom line: Weigh pros and cons

Many of the harms we’ve discussed are statistically significant, and yet they are of questionable significance. Almost all the increased risks are relative risks. The absolute, or overall, risks are often quite low.

We haven’t focused on the potential medical benefits here. But many people use pot — even rationally — for benefits they perceive to be greater than the harms we’ve listed.

We unquestionably need more research, and more evidence of harms may emerge. But it’s important to note that the harms we know about now are practically nil compared with that of many other drugs, and that marijuana’s effects are clearly less harmful than those associated with tobacco or alcohol abuse.

People who choose to use marijuana — now that it’s easier to do legally — will need to weigh the pros and cons for themselves.

Disparate Impact and the Administrative Procedure Act

This post was co-authored with Eli Savit, an attorney and adjunct professor at the University of Michigan Law School.

In a New York Times op-ed this week, we argued that a Michigan bill that would impose work requirements on Medicaid beneficiaries violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits any program receiving federal funds from discriminating on the basis of race. As currently written, the bill exempts people who live in counties with high unemployment from the work requirement, but doesn’t extend the same accommodation to cities with high unemployment. Because Michigan’s black communities are concentrated in cities, the facially neutral exemption will disproportionately benefit white, rural Michiganders over their black, urban counterparts.

But so what? In its 2001 decision in Alexander v. Sandoval, the Supreme Court held that Title VI doesn’t supply a private right of action to vindicate a disparate impact claim. So if Michigan passes this bill, and the Trump administration declines to enforce Title VI, is there any legal remedy? Suing the Trump administration for declining to take disciplinary action against Michigan won’t work. Under Heckler v. Chaney, HHS’s decision to decline to enforce Title VI is unreviewable.

We nonetheless think the Michigan bill is vulnerable to legal challenge. The key, in our view, is that Michigan can only impose work requirements if it gets a waiver from HHS under section 1115 of the Social Security Act. And the Second, Third, and Ninth circuits have all held, consistent with the presumption favoring judicial review of agency action, that the decision to grant an 1115 waiver is reviewable under the Administrative Procedure Act. The APA thus supplies the cause of action that Title VI doesn’t.

It would be arbitrary within the meaning of the APA for HHS to grant a waiver that licenses Michigan to violate HHS’s own rules governing Title VI. At a minimum, HHS would have to offer a reasonable explanation for why, in the face of the exemption’s disparate impact, there’s a “substantial legitimate justification” for what Michigan wants to do. As we argued yesterday, it’s doubtful that HHS could meet that burden, even under a deferential standard of review. The disparate impact is blatant and a substantial justification for it is nonexistent.

Trying to use the APA as a vehicle to vindicate Title VI isn’t novel. Prior to Sandoval, however, the approach was a non–starter. The APA makes reviewable “final agency action for which there is no other adequate remedy in a court.” Before Sandoval, courts regularly entertained private disparate-impact claims under Title VI, so there was an “adequate remedy” that precluded APA review. As the D.C. Circuit reasoned in an opinion that ended the long-running educational dispute of Adams v. Richardson, “Congress considered private suits to end discrimination not merely adequate but in fact the proper means for individuals to enforce Title VI and its sister antidiscrimination statutes.”

Sandoval changed all that by eliminating a private right of action for disparate impact claims. Absent that “special, alternative remedy,” an APA claim to enforce an agency’s compliance with its Title VI regulations should now be viable.

The post-Sandoval case law on the question is thin, but what little there is reinforces that conclusion. As the Sixth Circuit has observed (albeit outside the Title VI context):

There is a major difference between a plaintiff attempting to obtain a remedy against a person subject to federal regulations, and a plaintiff attempting to hold an agency accountable for alleged violations of its own rules. Sandoval spoke to the former situation—alleged misconduct by a regulated person. But this case involves the latter situation—review of agency action.

In line with that reasoning, a California district court ruled last month in an environmental case that “neither a Title VI nor an equal protection claim constitutes an adequate remedy to an APA claim” when it comes to disparate impact. Indeed, the U.S. Justice Department has itself raised that possibility of APA suits to vindicate Title VI, and Justice Breyer made a related point in a concurrence in a case about the enforcement of the Medicaid statute.

In our view, the APA theory is sound. We’re less sure that the Supreme Court still believes, as it once did, that Title VI authorizes agencies to issue rules that prohibit policies that have a disparate racial impact. If the Court were to rethink that position, an APA challenge to the waiver couldn’t succeed. But who knows? Lower courts can’t indulge in armchair predictions about what the Supreme Court might do. They’re bound unless and until the Supreme Court reverses itself. And, under existing case law, the Michigan bill looks really dubious.

One final note. Because of persistent income disparities across race, minority groups are overrepresented in the Medicaid population. As a result, any waiver that allows states to constrain Medicaid eligibility will have a disparate racial impact—and, as such, is vulnerable to the argument that HHS granted the waiver in contravention of its own Title VI regulations.

The argument hasn’t been pressed in the high-profile lawsuit challenging Kentucky’s work requirements, but maybe it should be. Sure, it’s possible that HHS can offer a “substantial legitimate justification” for work requirements—at least one that can survive APA arbitrariness review—notwithstanding their racial disparate impact. But given the fragility of the justifications for work requirements, an APA-cum-Title VI claim has a decent shot at succeeding—at least as good a shot, we think, as the arguments currently being raised.

May 9, 2018

Healthcare Triage News: More Medicaid News, but This Time Its Not All Terrible!

This week, Seema Verma announced that the administration would not approve several requests by states to place lifetime limits on Medicaid benefits. How about that? The CMS doesn’t do much to protect benefits these days, but this is a pretty good one. Work requirements are still happening though, so there’s that.

On snoring, 5

You don’t care about this, but it’ll haunt me for the rest of my life: When I started this series “on snoring” I had a pile of papers that I thought were about snoring and a separate pile that I thought were about obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). In truth, they’re both on the same continuum of sleep disordered breathing (SDB), and therapies that address one also address the other. The only difference in the piles of papers is that the word “snoring” appears in one and not the other. That’s not a good reason to separate the piles, but I did.

So, “On snoring” was poor choice of title for the series — a huge, consequential mistake from which I may never recover. Such are the perils of blogging. But I can’t turn back now. I’ve got three more papers in my “snoring” pile, notes on which follow. The part about the rabbits is my favorite.

Gagnadoux, F., Nguyen, X.L., Le Vaillant, M., Priou, P., Meslier, N., Eberlein, A., Kun-Darbois, J.D., Chaufton, C., Villiers, B., Levy, M. and Trzépizur, W., 2017. Comparison of titrable thermoplastic versus custom-made mandibular advancement device for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Respiratory medicine, 131, pp.35-42.

“Observational prospective cohort studies indicate that regular CPAP therapy is also associated with a lower risk of driving-related accidents and cardiovascular events [4,5].” Comment: (1) I haven’t chased down any statistics on it yet, but I’ve heard that many (a high proportion of) auto accidents are caused by people falling asleep at the wheel. Those with untreated sleep apnea are at much higher risk of doing so. (2) The second of these citations includes in its abstract that OSA can activate pathways that cause inflammation, suggesting my inference that my OSA and my tendinitis are connected.

“[A]pproximately 40% are at risk of nonadherence [to CPAP] especially if they have mild to moderate OSA [6]. Mandibular advancement devices (MAD) have emerged as the main therapeutic alternative for OSA. Despite the superior efficacy of CPAP in reducing sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), most randomized

trials comparing MAD and CPAP in OSA have reported similar heath outcomes in terms of sleepiness, neurobehavioral functioning, quality of life and blood pressure [3,7-10].When MAD therapy is prescribed, practice guidelines also suggest with a low quality of evidence to use a custom, titratable MAD over noncustom

devices [11]. However, potential disadvantages of these custom-made MAD are the cost and delay required to manufacture the device. In addition, not all patients benefit from MAD, and presently no method exists to predict the outcome prior to fabrication of the device [12]. Thus, a trial with an inexpensive thermoplastic

titrable MAD would be of great interest.” Comment: Yes. Yes it would. More precisely, I would like to see more studies of OTC (non-custom) MADs (see below).

Unfortunately, this is not that study (see below). It compares a less expensive, thermoplastic MAD (BluePro®) with the more expensive, custom ones (AMO® and Somnodent®, all from SomnoMed). The difference is in how the devices are molded to teeth. Thermoplastic is, as the name suggests, self-molding by heating the material, biting, and then cooling. The other devices require dental impressions, which is a more expensive process. This was a non-randomized study and included patients in the thermoplastic arm that were younger and had lower BMI than the other arm.

“This study demonstrates the efficacy of a titrable thermoplastic MAD in reducing SDB and related symptoms in patients with mild to severe OSA. Reported compliance at 6 months was high despite more dental discomfort than with custom-made MAD.”

There are other studies. “Among thermoplastic devices evaluated in the literature, those without chairside impressions and/or customized design were found to be poorly effective and uncomfortable, leading to poor compliance and treatment discontinuation [23,24] […] Discrepant findings were obtained in previous studies evaluating the impact of ready-made or partially customized MADs on SDB and related symptoms. The TOMADO randomized trial compared non-adjustable “boil and bite” thermoplastic appliances with a custom-made MAD for the treatment of mild OSA [23]. All devices reduced AHI compared with no treatment but compliance was lower with the self-moulded device, which was the least preferred treatment at trial exit. Friedman et al. [27] found that a custom-made device achieved higher rates of objective improvement

and cure of OSA than a thermoplastic MAD. Self-reported adherence was present in 54% of patients on thermoplastic MAD versus 65% on custom-made MAD. At 6 months, only one third of patients on thermoplastic MAD were still considered adherent, compared to 51% in the other group. Using the same thermoplastic device Vanderveken et al. [13] found that thermoplastic MAD was completely or partially effective in 31% of patients versus 60% for the custom-made MAD. In a recent randomized study, Johal et al. [24] reported a response rate of only 24% with a thermoplastic MAD versus 64% in the custom-made arm.”

“Although open trials with thermoplastic devices showed mild side effects [25,31,32], most comparative trials found that tolerance and overnight retention were lower with thermoplastic than custom-made devices [13,23,24,27]. Most patients expressed preference for the custom-made device in cross-over trials [13,24].”

Upshot: It seems like it is possible for one to relieve snoring and OSA symptoms with some OTC (non-custom) oral appliances. Which ones? Beats me. Maybe digging into the references would be informative. On the other hand, it’s reasonable to be concerned that symptom relief will not be as great (or not occur at all) with the OTC devices, relative to custom-made ones. Moreover, it’s pretty clear that the OTC ones are harder to tolerate. In the end, it seems it would be hard for a typical patient who wants to address a snoring problem to avoid spending considerable money on a custom device.

Guzman, M.A., Sgambati, F.P., Pho, H., Arias, R.S., Hawks, E.M., Wolfe, E.M., Ötvös, T., Rosenberg, R., Dakheel, R., Schneider, H. and Kirkness, J.P., 2017. The Efficacy of Low-Level Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for the Treatment of Snoring. Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 13(5), pp.703-711.

About 40% of the adult population snores.

There are studies that suggest snoring may contribute to hypertension and cardiovascular disease, at least in certain populations (diabetics [9], men under 50 years old [10], rabbits [11], 18-50 year olds [12]).

“Snoring constitutes a recognized source of noise pollution that may disrupt the sleep of bed partners and degrade a couple’s overall quality of life [13,14].” See also [39,40].

“Agents that reduce nasal airflow obstruction including nasal splints, nasal saline sprays, nasal decongestants, and anti-inflammatory medications have limited clinical efficacy in snorers [2].”

“Despite the wide range of available treatment options, many snorers remain untreated due to limited tolerability and/or therapeutic efficacy of therapies.”

“This study demonstrates that low-level CPAP during sleep is highly efficacious in mitigating snoring in habitual snorers without significant sleep apnea. On CPAP titration nights, we found that CPAP decreased snoring frequency markedly at all levels of snoring intensity. Progressive decreases in snoring severity were observed when CPAP was increased stepwise from 0 to 4 cm H2O.”

Scherr, S.C., Dort, L.C., Almeida, F.R., Bennett, K.M., Blumenstock, N.T., Demko, B.G., Essick, G.K., Katz, S.G., McLornan, P.M., Phillips, K.S. and Prehn, R.S., 2014. Definition of an effective oral appliance for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring: a report of the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. J Dent Sleep Med, 1(1), pp.39-50.

“Sleep disordered breathing constitutes a spectrum of repetitive upper airway narrowing episodes during sleep characterized by snoring, elevated upper airway resistance, and/or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).”

“Common symptomatic manifestations include hypersomnolence [4], insomnia, neurocognitive deficits, [5,6]

bed partner disturbance, mood disorders, [7,8] nocturia, [9] and fatigue. Diminished reaction time and increased susceptibility to motor vehicle crashes have also been reported. [10,11] OSA is an independent risk factor for the development of hypertension, coronary artery disease, epithelial dysfunction leading to ischemia, [12] cardiac arrhythmias, [13] stroke, insulin resistance, [14,15] and all-cause mortality. [16-22]”

“Pierre Robin was the first to document the use of a mandibular advancement oral appliance for the treatment of nocturnal airway obstruction in 1923. However, oral appliances were apparently forgotten until 1982, when Cartwright and Samelson reported the use of a novel tongue retainer. [38] Within a few years, several authors rediscovered mandibular advancement oral appliances. [39]”

This paper includes a fine lit review. But I think what I’ve read before is enough.

There’s No Justification for Michigan’s Discriminatory Work Requirements

This post was co-authored with Eli Savit, an attorney and adjunct professor at the University of Michigan Law School.

As we highlighted yesterday in the New York Times, a Michigan bill to impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients would have severe racially discriminatory effects. The bill exempts people from the work requirement if they live in a county with over 8.5% unemployment. In Michigan, though, the only counties that meet that criterion are rural and overwhelmingly white. By and large, the state’s black population—which is concentrated in high unemployment cities like Detroit, Flint, and Muskegon—will not qualify for work-requirement exemption.

Could a court strike down Michigan’s Medicaid work requirements because of these discriminatory effects? We think so. Michigan needs a waiver from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) before it can move forward with its work requirements. If HHS grants that waiver notwithstanding Michigan’s violation of HHS’s own disparate impact regulations, the waiver could well be struck down as arbitrary and capricious. (We’ll have more to say about this potential route into court tomorrow.)

Yes, agencies get a lot of deference when applying their own regulations, including their Title VI regulations. For a court to invalidate the work requirement, Michigan’s Title VI violation has to be so clear-cut that HHS’s decision to grant the waiver was “arbitrary.” But a challenge to Michigan’s work-requirement bill could probably meet even that demanding standard.

Courts and agencies—including HHS—use a three-part test to determine whether a facially neutral practice imposes an unlawful disparate racial impact. First, does the practice have a racially disproportionate effect? Second, if the practice has a racially disproportionate effect, is there nevertheless a “substantial legitimate justification” for the practice? Third, even if there is a legitimate justification, is there an alternative that will achieve the same objective, but with less discriminatory effect?

Establishing a disproportionate racial effect should be a cinch. As things currently stand, residents in 17 rural counties would be exempt from Medicaid work requirements. In those 17 counties, African-Americans make up just 1.7% of the population, though African-Americans make up 14.2% of Michigan’s total population. Indeed, the total number of black people living in the seventeen exempt counties is around 5400—approximately 0.3% of Michigan’s total black population.

The exempt counties are small and sparsely populated. Still, they make up 3% of Michigan’s population as a whole. That means the average Michigan resident is ten times more likely to be a beneficiary of the exemption than the average black Michigan resident.

That takes us to the second element: whether there’s a “substantial legitimate justification” for exempting people at the county level, but not the city level, from work requirements. The co-sponsor of the Michigan legislation is already trotting out an argument to defend the county-level exemption: namely, that people should be looking for work not just in their city, but all across their county. “I don’t know why anybody in Flint would say we need to be treated separate than Genesee County,” State Senator Mike Shirkey told reporters. “I mean, is it too much of an expectation . . . if you happen to live in Flint, to look for a job in Genesee County? And the same argument applies to Detroit and Wayne County. How granular do you want to get?”

That kind of argument ignores the lived reality of Michigan’s urban communities. Low-income residents in Michigan’s cities are significantly less able to travel for work—even to another part of the county—than people in rural communities. That’s because public transit is virtually non-existent in Michigan. In the state that put the world on wheels, you need a car to get around. (For an illustrative story of how difficult it is to get around metro Detroit without a car, check out this profile of Detroiter James Robertson, who had to walk 21 miles a day to get to and from his job in the Detroit suburbs.)

The percentage of Michigan’s urban households who lack access to cars is sky-high: around 20% in Flint and Muskegon, and over 25% in Detroit. By contrast, in counties that would be exempt from the Medicaid work requirements, virtually everyone has a car—in those counties, car ownership rates hover at around 95%. The disparity is due to the fact that Michigan has the highest auto insurance rates in the nation, with urban rates sometimes three times as high as they are elsewhere in the state.

If Michigan really wants to encourage people to seek jobs in every geographic location they can reasonably access, this bill gets it exactly wrong. It provides an exemption to rural residents who are likely to have cars and, as a result, can travel (even across county lines) for work. At the same time, it punishes urban residents for their inability to travel to jobs they can’t possibly access.

That’s totally illogical. And that illogic should sink the policy. To show that a policy serves a “substantial legitimate interest,” the state must demonstrate a “manifest demonstrable relationship” between its purported objective and the challenged policy. A policy that supposedly exists to encourage mobile people to travel for work—but actually punishes immobile people, while giving mobile people a break—doesn’t cut it.

As for the third element, it’s not at all difficult to come up with less discriminatory alternatives that achieve the same objective. The bill’s sponsors could recognize that poorer people in its urban centers have at least as much trouble accessing jobs as those in hardscrabble rural areas, and extend the exemption to cities with high unemployment. It could provide the exemption by ZIP code instead of by county. Or it could come up with a more holistic method of determining when someone should be exempt from the work requirement: one that takes into account the jobs realistically available to a person given his or her education level, access to transportation, and so forth.

The Michigan legislature’s failure to grapple with these issues suggests that, at bottom, the county-level exemption is about politics, not policy. The elected representatives from white, rural counties that would qualify for the exemption are Republicans who support the work-requirement bill. Yet they recognize that work requirements will harm their own constituents—and so they’re exempting them, and not other Michiganders, from the dire consequences of losing health insurance.

That’s immoral and inequitable. And, given the bill’s severe racial disparities, it’s also unlawful.

In March 2018—the most recent month for which data is available—the unemployment rate in Flint was 10.4%, the unemployment rate in Muskegon was 9.2%, and the unemployment rate in Detroit was 8.7%. All unemployment data cited in this post comes from the Michigan Bureau of Labor Market Information and Strategic Initiatives. It can be accessed online at http://milmi.org/datasearch.

Figures are per the 2017 U.S. Census population estimates, available at census.gov.

In fact, the legislation, if enacted, will almost certainly exempt far more white rural residents than in those 17 counties. That’s because the legislation says that people become exempt from the work requirement if the unemployment rate in their county, at any time, reaches 8.5%. But thereafter, that person remains exempt so long as the unemployment rate in the county exceeds 5.0%.

In addition to the 17 counties that currently have unemployment rates over 8.5%, there are a number of predominantly white, rural counties where unemployment typically reaches 8.5% at some point during the year. Residents of those counties, too, would qualify for the exemption, and would maintain that exemption going forward unless the unemployment rate in their county dipped below 5.0%.

May 8, 2018

Michigan’s Discriminatory Work Requirements

That’s the title of an op-ed that Eli Savit and I just published at the New York Times.

For those who are too poor to afford health insurance, Medicaid is a lifeline. This joint federal and state program doesn’t care whether you’re white or black, Christian or Muslim, Republican or Democrat, a city-dweller or a rural resident. In states that expanded their Medicaid programs under Obamacare, all you have to be is poor enough to qualify.

But maybe not in Michigan. In late April, the state Senate passed a bill that would require Medicaid beneficiaries to find work or else lose their coverage. The bill, now under consideration in the House of Representatives, has come under fire for harming the poor and disabled, as well as for imposing needless paperwork burdens on struggling families. More than 100,000 people may lose health insurance if it passes.

There’s another flaw in the bill, however, one that exposes it to serious legal challenge: It’s racially discriminatory.

We’re indebted to Nancy Kaffer of the Detroit Free Press and Danielle Emerson of the Great Lakes Beacon for first drawing attention to the bill’s racial disparities. In our op-ed, Eli and I explain why those disparities will make Michigan’s proposed approach vulnerable to legal challenge.

We couldn’t fit everything we wanted to say into the op-ed, so we’ll have follow-up posts over the couple of days expanding on the legal theory and explaining why there’s no legitimate justification for the county-level exemption.

May 7, 2018

Healthcare Triage: Wanna Be Happy? Buy Back as Much Time as You Can Afford.

Studies indicate that bickering about the hard work of keeping house, taking care of kids, cooking, and mowing the lawn can contribute to relationship problems and divorce. Going to restaurants and hiring out some of the work can help. This is obviously not possible for most people, but if you can work it into your budget, buying back your time is one of the most satisfying ways you can use disposable income. Also, there seems to be a bigger bang for your buck if you’re NOT rich.

This episode was adapted from a column Austin wrote for The Upshot. Links to sources can be found there.

May 5, 2018

The Value-Based Drug Formulary (part 2)

Gilbert Benavidez is a Policy Analyst with Boston University’s School of Public Health. He tweets at @GBinsolidarity.

Earlier I wrote about CVS’s value-based formulary management system, which includes the strategic removal of drugs from formulary, based on clinical effectiveness and cost-appropriateness and done in effort to both align drug price with value and drive down costs for payers. I also mentioned relationship CVS has with the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). Among pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs), this type of value-based activity is not unique to CVS.

In another recent example of value-based removal from formulary, the largest PBM in the US and a CVS competitor, Express Scripts, recently cut out Amgen’s Repatha (evolocumab) in favor of Sanofi and Regeneron’s Praluent (alirocumab).

Express Scripts did this for two reasons:

Express Scripts struck a deal with Sanofi and Regeneron to lower the price of Praluent to be nearly in line with ICER valuation of the drug, in exchange for quick approvals of treatment requests. (Amgen has fought back against this valuation and instead defended their price)

Studies found that Praluent lowered risk of heart attack, stroke and death, while Repatha only lowered heart attack and strokes.

Express Scripts’ strategic removal is in line with rival CVS’s strategy of guiding patients toward clinically effective, cost-appropriate treatments. Express Scripts CEO Steve Miller noted that the new net price will be close to the “low end” of ICER’s valuation of Praluent ($4500-8000 per year).

The move further exemplifies ICER’s ability to influence drug prices through its value-based drug pricing method.

May 4, 2018

The Value-Based Drug Formulary

Gilbert Benavidez is a Policy Analyst with Boston University’s School of Public Health. He tweets at @GBinsolidarity.

CVS, the second largest pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) in the US, takes drugs off its formulary if there’s a cheaper drug that’s just as clinically effective. This strategy is dubbed “value-based management.”

In July, 2017, Troy Brennan, Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Officer of CVS Health wrote, “A drug can be strategically removed from formulary for an indication where it doesn’t work as well and other lower-cost, similar or more effective drugs are available.” Decisions are externally validated by independent organizations to ensure appropriateness.

The goal? To guide patients toward “clinically effective, cost-appropriate treatments.”

About their value-based management strategy, Dr. Brennan wrote,

Specialty guideline management or prior authorization (PA) review helps capture information about what indication a drug is being used to treat, and takes into account key data such as the patient’s use of prior therapies and other clinical information. Once this information is obtained, utilizing tools such as formulary exclusion, PA, step therapy, and diagnosis review can help ensure that patients are being directed to clinically effective, cost-appropriate treatments.

A drug could be placed on a formulary for only the specific indication(s) for which it is more effective. Or, a drug could be included on a formulary for all approved indications, but the manufacturer would be required to pay a higher rebate when the drug is used for an indication for which it is proven to be less effective or beneficial. Alternatively, the manufacturer of a less effective drug could be required to offer lower pricing in order to have it included on the formulary. Manufacturers of more effective drugs for the same indications may also be required to provide more favorable pricing and rebates in return for preferred formulary placement. Promoting this kind of competition lessens the overall cost impact for payers, and enables more favorable formulary placement for the most effective treatment options.

This strategy is used, for example, in CVS’s autoimmune and Hepatitis C categories. Manufacturers are incentivized to lower prices of drugs during negotiation with CVS, lest they be left out of formulary in favor of more clinically effective and cost appropriate drugs.

CVS has been thinking along these value-based lines for a while now. A new development, acknowledged in a post earlier this week, is that it is working with the Institute for Economic and Clinical Review (ICER), as well as an independent advisory board of health economists, to develop new, innovative plan designs to continue attempting to align drug price and value and look for new opportunities to apply value-based management strategies.

This is consistent with a tweet by Harlan Krumholz that goes a bit further:

One of the most interesting comments by Troy Brennan was that employers are starting to put in their benefit plans that they will not pay for drugs that are more expensive than $100K per quality adjusted life year. Now that is a change. @YaleMed

— Harlan Krumholz (@hmkyale) April 26, 2018

A formulary with an cost/QALY threshold would be value-based in a very strict sense. There’s a lot here unanswered though. Which employers? When will we see these formularies?

May 3, 2018

The best systematic review of oral appliances for snoring/sleep apnea

Naturally, I have not read all the literature on the effectiveness of oral appliances (OAs) for snoring and sleep apnea among adults, nor will I ever. But this 2015 systematic review/meta analysis by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine sets a high bar for organization. For that reason alone I’ll call it “the best.” But, maybe it’s not best by other standards. I really don’t know.

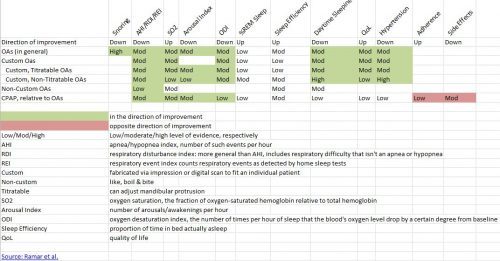

The only thing it lacks is a table to summarize the findings, so I made one. An image of it is below. The Excel spreadsheet is here.

I’m not going to define all the terms. They’re in the image (click to enlarge) or spreadsheet. But, if you know them and want to understand the chart’s cells, the words low/med/high mean level of evidence (higher is best); green means in the direction of improvement, red the opposite. (The only two red cells are for adherence and side effects, indicating that CPAP is worse in those categories, relative to OAs.) Cells with no color means no statistically significant finding. Cells with no values mean no studies reported.

Some takeaways:

Oral appliances are effective in all the categories that CPAP is effective, but have the advantage of better adherence and fewer side effects. CPAP is more effective in addressing many symptoms of sleep apnea, but not statistically significantly better in many other categories.

Custom OAs (those fabricated via an impression or digital scan) perform better than non-custom OAs, but there aren’t a lot of studies on non-custom OAs.

Non-titratable OAs perform quite well, to my surprise. An advantage of them, a dentist who makes OAs told me, is that they’re less prone to breaking.

OAs are effective for snoring, with a high level of evidence.

I’m surprised at the %REM and sleep efficiency findings. Not consistent with my N=1, subjective experience. Cool.

OAs can be effective in reducing hypertension.

The one big bummer is that, at least for studies that made the cut for this systematic review, we don’t know much about non-custom OAs. That sucks because they’re the least expensive way (among those in the chart) to try to address snoring, a super common and bothersome problem that isn’t covered by insurance. Few snorers would want to shell out the big bucks for a custom OA or CPAP. It’d be nice to know more about the cheaper options.

(Having said that, I am aware of at least one study of non-custom OAs for snoring. It’s too recent for this review. I’ll blog about it soon.)

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers