Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 105

April 25, 2018

On snoring, 4

Marklund, M., Carlberg, B., Forsgren, L., Olsson, T., Stenlund, H. and Franklin, K.A., 2015. Oral appliance therapy in patients with daytime sleepiness and snoring or mild to moderate sleep apnea: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA internal medicine, 175(8), pp.1278-1285.

The conclusion: “A custom-made, adjustable oral appliance reduces obstructive sleep apnea, snoring, and possibly restless legs without effects on daytime sleepiness and quality of life among patients with daytime sleepiness and snoring or mild to moderate sleep apnea.”

“Young and colleagues [1] estimated that 24% of middle-aged men and 9% of women have sleep apnea,with 5 or more apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep, but only 4% of men and 2% of women had the combination of sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness.” Comment: (1) This is a study from 1993. (2) I am not surprised that many with sleep apnea report that they don’t feel sleepy. I would have said I didn’t. I wonder how many have memory degradation, which I experienced. (N=1* in my case, naturally, and confounded with age. Maybe it’s not the apnea!)

Having said that, the criteria for entry into this study included that “[t]he patients also had daytime sleepiness according to 1 or more of the following criteria: (1) an ESS score of 10 or higher; (2) daytime sleepiness assessed as ‘often’ or ‘always,’ or (3) unwillingly falling asleep during the daytime assessed as ‘sometimes,’

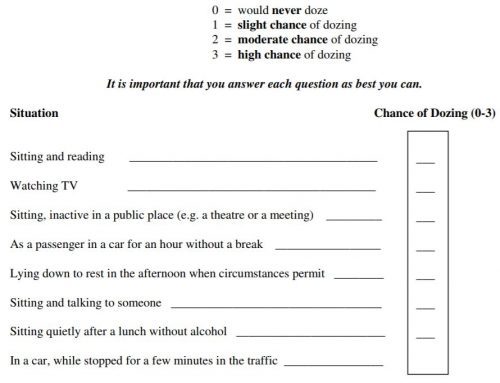

‘often,’ or ‘always’ […] or (4) an irresistible tendency to fall asleep during the daytime 1 or more times per week.” Comment: OK, maybe I’d agree to fall into the 4th category. As for the ESS [Epworth Sleepiness Scale], I was rated on it multiple times in my sleep apnea journey. It’s the sum of responses to the prompts in the image below. Every time I filled it out I faced the following conundrum: I couldn’t figure out if intent mattered. That is, in all but one of these situations I would not ever fall asleep if I didn’t decide I wanted to, no matter how sleepy I was. The exception is “lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit” because I literally only do that if I want to sleep (so intent and the situation are the same thing). So I always scored a 3 when, in fact, I have dozed in several of these situations (because I decided to and it was too much bother or otherwise impossible to find a place to lie down — intent!). I could easily talk myself to a 7-10 on this and, believe you me, if I thought it mattered one whit in terms of getting treatment I needed, I would have. In truth, I don’t think it mattered at all and I doubt very much if anyone looked at my myriad completions of the ESS. I hate these kind of questionnaires. Seems like useless patient busywork. If I’m wrong, I’d sure like to know.

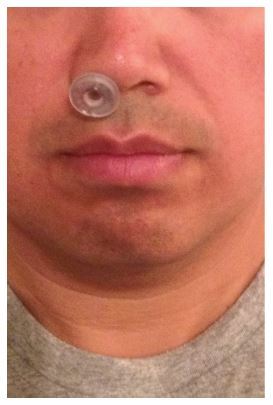

Below are pics of the oral appliance (top, a mandibular advancement device) and placebo (bottom, a thingy that just sits at the roof of the mouth, if I’m understanding the text) used in the study. What surprised me (because I just haven’t stumbled across it yet) was just how little the lower jaw is thrust out by a mandibular advancement device such as this: a mean of about 7mm in this study.

N=45 patients in the treatment arm; N=46 placebo.

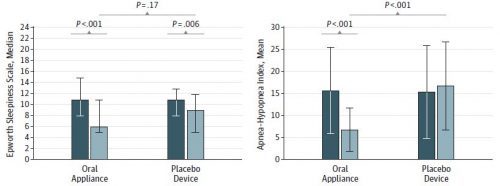

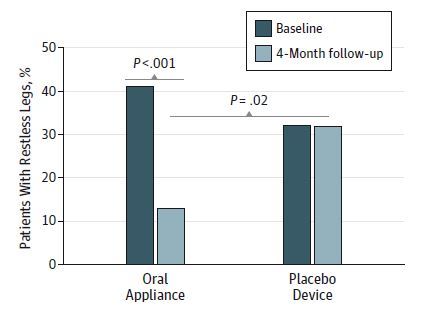

Below are some statistically significant findings, in graphical form. Lots more in the paper. The restless legs results are interesting. I did not know that sleep apnea is associated with restless legs. I do know from personal experience that apnea/hypopnea events can be associated with sleep starts, which can feel like jumping legs (and other body parts). I wonder if the two are distinguished in this and other studies.

* A reader wrote me recently expressing dissatisfaction with my N=1 blogging about sleep apnea. If you feel that way, save yourself and me the bother and don’t email me. I cannot please everyone. Others like them and, truth be told, I write them for myself, so it doesn’t really matter what anybody thinks. You don’t have to read them! You will note, however, that I have weaved in a lot of links to evidence in many posts, including this one. I think the purely anecdotal ones are obvious (no links to studies).

JAMA Forum: Evidence Suggest That Meal Assistance Programs Do More Than “Sound Good”

My latest over at the JAMA Forum:

About a year ago, Mick Mulvaney, director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), got himself into a bit of trouble when he argued that cuts to the Community Development Block Grant program were justifiable because those programs were “just not showing any results.” The example he used—Meals on Wheels—as programs we can’t fund “just because they sound good” elicited a significant amount of pushback, even from me.

A new study argues that such programs are even better than we thought.

California, Coffee and Cancer: One of These Doesn’t Belong

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2018, The New York Times Company).

About two-thirds of smokers will die early from cigarette-based illnesses. Cigarettes are also very addictive. Because of this, it seems reasonable to place warnings on their labels.

If a Los Angeles Superior Court judge has his way, California businesses will have to put similar warnings on something else that can be addictive, coffee. His ruling, which is being challenged by coffee producers, is harder to justify in terms of health — if it can be justified at all.

California’s Proposition 65, enacted in 1986, mandates that businesses with more than 10 employees warn consumers if their products contain one of many chemicals that the state has ruled as carcinogenic. One of these chemicals is acrylamide. Like many other substances, acrylamide causes cancer in rats — when they are pumped full of huge doses in ways that don’t approximate real life.

In humans, the data are far less clear. The American Cancer Society(which does not shrink from saying things cause cancer) reports on its website that “there are currently no cancer types for which there is clearly an increased risk related to acrylamide intake.”

Other organizations, such as the International Agency for Research on Cancer, have warned that acrylamide is a “probable human carcinogen.” But this is based almost entirely on animal studies, and the agency has backpedaled in recent years. It’s also worth pointing out that of the nearly 1,000 substances the agency has classified, it has ruled almost none to be non-carcinogenic.

Regardless, acrylamide isn’t an industrial additive. It’s a chemical that is made almost any time you cook starches at temperatures above 250 degrees Fahrenheit. You can make acrylamide from frying, baking, broiling or roasting — essentially anything that isn’t boiling or microwaving.

Toasted bread contains acrylamide. So do fried and roasted potatoes. So do roasted coffee beans. Acrylamide formation occurs whether this cooking is done by a corporation or by you in your home. It’s made even when you cook organic food — there’s just not much of a way to avoid it. Acrylamide is found in about 40 percent of the calories consumed by people in the United States.

Some California businesses that serve food and drinks, unwilling to wage a legal fight against Proposition 65 or possibly hedging against fines, have already posted warnings about acrylamide over the years. A handful of makers of potato chips and fries also agreed to reduce their levels of acrylamide by 20 percent. There have been no studies showing this has made any difference in health, certainly not with respect to cancer.

Coffee has had acrylamide in it since humans started drinking it. The Food and Drug Administration, in its Guidance for Industry Acrylamide in Foods, reports that there is no viable commercial process for making coffee without producing at least some acrylamide.

If there were such a process, there wouldn’t be a reason to use it. After all, we have a wealth of evidence about coffee’s effects. Meta analyses have shown that coffee is associated with lower risks of liver cancer, and no increased risk of prostate cancer or breast cancer. When we look at cancer over all, it appears that coffee — if anything — is associated with a lower risk of cancer.

Even the International Agency for Research on Cancer has essentially reversed itself. In 2016, it declared that “drinking coffee was not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans.”

The more serious problem with California’s law is one of effect size. Health, and cancer, aren’t binary. Consumers can’t just be concerned with whether a danger exists; they also need to be concerned about the magnitude of that risk. Even if there’s a statistically significant risk between huge quantities of coffee and some cancer (and that’s not proven), it’s very, very small.

Cigarettes have a clear and easily measured negative impact on people’s health. Acrylamide, especially the acrylamide in coffee, isn’t even close.

Warning labels should be applied when a danger is clear, a danger is large and a danger is avoidable. It’s not clear that, with respect to acrylamide, any of these criteria are met. It’s certainly not the case regarding coffee. Whatever the intentions of Proposition 65, this latest development could do more harm than good.

In 1994, a systematic review in The Journal of Public Policy and Marketing on the unintended consequences of warning messages said, “The emphasis of policymaking in the past has tended to focus more on the identification of potential hazards than on helping consumers develop an understanding of the magnitude and probability of a potential hazard that can be used for informed decision making.”

If Americans slap a label on every substance that has the potential to cause cancer, eventually those labels will stop having any meaning. If nearly inconsequential dangers get the same warning as significant dangers, people might start ignoring preventive efforts entirely.

That went well: CPAP, night 1

Don’t worry, I won’t blog every night of my CPAP use. But the first time is special, isn’t it? It went extraordinarily well, though there is still room for improvement — and, I expect to improve.

My insurance company sprang for what seems like about the best CPAP machine on the market: ResMed AirSense 10. I don’t know if it is actually the best on the market, but it sure is nice. I was once worried I’d get a machine that was noisy. This one is silent, once the mask is on. Can’t hear it at all.

Other niceties: It’s smallish/lightish. It automatically adjusts pressure as needed. It can back off the pressure for exhale. I thought this would be obtrusive and wake me up. It’s so gentle, I didn’t notice it at all.

It can heat the tube so condensation doesn’t build. It’s got lots of customizable features for comfort (humidity, temperature, and the like). The menus are easy to use. It gives feedback, either on the device or via an app. Once a data card is plugged in, the user can get even more data. (You bet I will!)

I opted for a “nasal pillows” mask, as it has the smallest facial footprint and is most similar to Provent, with which I had already become comfortable. I believe I correctly surmised this would be the easiest transition. However, I was worried the silicone pillows would irritate my skin. Perhaps they would have, but as a precaution I applied some non-petroleum skin product before bed (this, because it’s what I have and use for my lips anyway [trumpet player]). I think that helped, and it certainly could not have hurt.

I was worried my nose would feel sore after hours of use (not the skin, but the structure). Didn’t happen. I was worried I’d get a headache from the pressure. Nope.

I wore the mask for 7 hours, starting at 9PM, a half hour before sleep, and ending at 4AM, after which I slept another hour. I took a quarter dose (2.5mg) of Ambien before bed, just to get me started. The machine tells me I needed 5.5 cmH2O of pressure. I’m not sure if that’s a max or average. Either way, it’s low, consistent with my mild case. That’s why Provent worked, and probably an oral appliance would too.

I had 0.1 apnea/hypopnea events per hour. Since I only used the thing for 7 hours, I’m not sure how it got this number. It implies I had less than one over the period of use. I think these should be quantized in integers, no? (Excuse me, but was that a half a snore I heard? Nonsense.) So, let’s call this zero, shall we?

There’s a bit of room for improvement. First, I want to use this Ambien-free, which I’m sure I will get to in a few days. Second, I want to use it for the full night, something like 10PM-6AM. It’s normal to need to remove it as one adjusts, but ideally one should ultimately leave it on the full night.

The bottom line here is that my original fear of CPAP machines was an evidence-free bias. One night in, I’m pretty happy. Perhaps I’ve got some awful stuff ahead of me — maybe my nose will get sore or I will never get fully used to the thing. But this is a good start and better than I’d dared to hope.

PS: It’s got to help that I want this therapy to work, and I’m highly motivated and informed. I am a light/fussy sleeper, so I could easily sabotage treatment by getting annoyed with everything that’s unusual. It would not take much for me to mind-game myself into insomnia. A good attitude goes a long way. #CognitiveBehavioralTherapy

April 24, 2018

Healthcare Triage: Do Antidepressants Work or What?

A huge meta-analysis came out recently looking at how effective antidepressants actually are. It turns out, the results are complicated, and we had a hard time reducing all the stuff in this study to a headline. So, the title’s a question, and that’s the way it is.

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to sources can be found there.

JAMA Pediatrics Podcast – How did the new AAP guidelines on hypertension change the prevalence and severity of the condition?

As I mentioned in a previous post, I’m now the Web and Social Media Editor at JAMA Pediatrics. We’ve got a podcast where I discuss a paper from the journal. I do my best to pick good ones.

Please consider giving this a listen, and subscribe! Doing so makes it more likely that I’ll be able to keep doing this.

This week, I’m covering “Change in Prevalence and Severity of High Blood Pressure in Children After Publication of the 2017 AAP Guideline on Management of Hypertension”:

This audio summary reviews a study that uses NHANES data to characterize changes in population prevalence of hypertension after publication in 2017 of the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents.

Audio summary here. Full article here. Subscribe to the podcast at iTunes, Google Play, iHeartRadio, Stitcher, or by RSS.

On snoring, 3

Chen, H. and Lowe, A.A., 2013. Updates in oral appliance therapy for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep and Breathing, 17(2), pp.473-486.

A lot of this is about obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), but a bit is about snoring. Anyway, in general what treats the former also is effective for the latter.

“OSA is associated with significant co-morbidities such as cardiovascular, metabolic/neurocognitive complications, motor vehicle crashes, and occupational accidents.” Comment: Causality isn’t so clear from this statement, but for some of these it seems more likely that it runs from OSA to the outcome (e.g., crashes/accidents).

“The American National Sleep Foundation 2005 poll based on Berlin questionnaire scores indicated the prevalence of OSA ranged from 16% to 37% in the 18–65+ age groups with the 50–64-year-old group having the greatest chance of being diagnosed with the disease in both gender groups (37% in males and 29%

in females) [3].” Comment: Dated, but I bet the prevalence has only gone up.

“Behavioral modifications for OSA treatment include weight loss, alcohol avoidance, and changes in sleeping

position.” Comment: Missing from the list is breathing exclusively through the nose. But, to be fair, I have not (yet) read a study that documents doing so can improve or eliminate OSA.

“In a recent practice parameters article published by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM), OAs are indicated for snorers, for mild to moderate OSA subjects, for severe OSA subjects who have not responded to CPAP, who are not appropriate candidates for CPAP, or whose previous attempts to use CPAP failed [5].”

“There are over 100 OA [oral appliance] designs available on the market which differ in the fabrication material, location of the coupling mechanism, titration capability, degree of customization, amount of vertical opening, and lateral jaw movement.” Most are mandibular advancement devices (MADs). Tongue retaining devices are not widely used, though are an option for patients who lack enough healthy teeth to anchor a MAD.

OAs work by altering the upper airway topology and (somehow) improving upper airway muscle tone.

“In a retrospective analysis of 175 male and 156 female patients who received dental care, 67% of the men and 28% of the women were identified as being at risk of at least mild OSA. Over 33% of the men and 6% of the women surveyed were predicted to have moderate or severe OSA [15]. However, a survey [16 (though dated)] showed that 58% of dentists in a group of 192 US practitioners could not identify common signs and symptoms of OSA; 40% knew little or nothing about OA therapy for OSA while 30% learned about it during postgraduate training. Some 54% have never consulted with a physician for a suspected OSA patient in their practice; 75% of dentists have never had patients referred to them by a physician.”

“Some researchers advised that pre-fabricated, over-the-counter appliances are less effective, less accepted, and not qualified as a screening tool to predict OA responders [45].”

A follow-up sleep test is recommended after adjustment to an OA is complete. However, these are rarely done due to insurance, access to a sleep lab, or (I bet) they’re not the least bit enjoyable for the patient.

This paper covers the evidence on effectiveness (they’re generally effective for snoring and OSA), side effects (discomfort and changes to dental structures) and compliance of/with OA. To my reading, long-term compliance rates don’t seem to be that much higher than to CPAP. The difference may be that many people stop using more quickly.

April 23, 2018

A press release is not enough (videos)

Frequently, I am asked to give my talk about translation and dissemination of health policy-relevant research to lay audiences — more frequently than I am able to do so. But versions of it are online. Videos are below.

Here’s the most recent:

Here’s a version from 2015 that includes Adrianna and Nick:

Improving reproducibility in research – There’s a Healthcare Triage series for that!

This will serve as my periodic reminder about this important work! – AEC

Very, very rarely in science do we achieve a result that we are absolutely, positively sure is correct. We almost always use statistics to give us some estimate of how likely we believe our results to be true, but that answer rarely equals 100%.

But we’d like to think that most of what we find, write up, and publish is correct. One way to define “correct” is as something that someone else can reproduce.

What do I mean by that? I mean that if someone else does the same experiment as me, in another time, in another place, they get the same result. I mean that – over time – people are able to get the same results I do when they perform similar experiments.

By this metric, many areas of science are falling far short of what we’d like.

Many are working on solutions to these issues. Journals are beginning to band together and discuss how to do better reviews. Many trials now need to be registered so that decisions have to be made about how to design, conduct, analyze, and report findings before the research takes place, while researchers are still behind the veil of ignorance.

The NIH has also gotten involved by calling for the creation of training modules to enhance data reproducibility. They are focusing their efforts on four domains:

Experimental design

Laboratory practices

Analysis and reporting

And the Culture of science

A few years ago, they put out a Request for Applications in this area, and we at Healthcare Triage were funded! We have tackled two of these domains, Experimental Design and Analysis and Reporting. We like to think we’ve got something to say about what makes a good study, well, good. We explored all the key concepts you need to consider in order to ensure that your research is as bias-free as possible.

And, we think we’re pretty good at analysis and reporting as well. Therefore, we talked about what makes a good paper, how to present and discuss your results, and how to avoid the mistakes many make in overselling their findings.

Both of these modules consist of many episodes, or chapters. They’re all short and sweet, they’re all freely available, and they’re open to anyone. If you’re interested in learning about CME for watching these videos, go here for Experimental Design and here for Analysis and Reporting.

We also would appreciate feedback. There’s a short survey you can fill out after you watch the series.

It’s hoped that these modules will help scientists at all levels improve the quality of their experiments and how they report them, and that by doing so, we might improve the problems we’re currently seeing in many areas of research in terms of reproducibility. Please share these videos widely!!!

This training module is part of a series funded by the National Institutes of Health under grant R25GM116146

P.S. Let me add that none of this would ever be possible without Stan Muller and Mark Olsen, my co-pilots at Healthcare Triage, John Green, who executive produces, and Austin Frakt and Jen Buddenbaum, who consulted on all of the scripts!

On snoring, 2 (a bad idea)

Camacho, M., Chang, E.T., Fernandez-Salvador, C. and Capasso, R., 2016. Treatment of snoring with a nasopharyngeal airway tube. Case reports in medicine, 2016.

Objective. To study the feasibility of a standard nasopharyngeal airway tube (NPAT) as treatment for snoring.

Methods. An obese 35-year-old man, who is a chronic, heroic snorer, used NPATs while (1) the patient’s bed partner scored the snoring and (2) the patient recorded himself with the smartphone snoring app “Quit Snoring.” Baseline snoring was 8–10/10 (10 = snoring that could be heard through a closed door and interrupted the bed partner’s sleep to the point where they would sometimes have to sleep separately) and 60–200 snores/hr.

First of all, yes “heroic snorer” is a clinical term. This is the best thing I’ve learned in my sleep apnea journey. Sadly, I am not an heroic snorer, but merely a wimpy snorer.

But, to the main line of the study: yow! An airway tube — sticking a tube down your throat — is a serious intervention. But, yeah, in theory it could work … if the patient can tolerate it. I think in hospital situations patients do so because they’re sedated or anesthetized, or otherwise not trying to rest.

Sure enough, in this case study the patient could not tolerate the airway tube for more than a few hours of sleeping. “[T]he utility of these tubes for snoring abatement is met with challenges.”

Another quote from the study: “Snoring is a common problem throughout the United States and worldwide, with literature reporting that 5–86% of men and 2–47% of women snore [1, 2].” Those are extremely wide ranges. The low ends are from this and high ends from this, both fairly dated. For what it’s worth, about one-third of French adult males habitually snore, according to this study, and here’s relatively recent work indicating half of Americans snore.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers