Clifford Browder's Blog, page 24

January 24, 2018

338A. Free: Dark Knowledge, chs. 1-3

Dark Knowledge

Chapters 1-3

1

I had never quite liked my uncle, and he had never quite liked me. But I had two good reasons to see him, an invitation and a question, so there I was, bound for his office on South Street, where bowsprits of anchored sailing vessels jutted high in the air overhead, while stevedores hustled huge bales and barrels and crates onto wagons or off of them, and iron-wheeled drays clattered on cobblestones amid smells of whale oil and sawn wood and brine. These were the sights and sounds and smells that three generations of my family, the Harmonys – tough, keen, hardbitten men -- had known and reveled in, as they set out for rampageous adventures in hot distant places. The very thought of those adventures always sparked me, fired me up. After a few minutes I stepped into the ship chandlery that still bore the sign HARMONY BROTHERS, even though my father had left the firm years before. Knowing me, the salesmen nodded but left me alone. I loved the sight of those mysterious instruments that I would never use – barometers and sextants and quadrants – and the smells of cordage, paint, canvas, and oils. Buoys and bells dangled from rafters, big windlasses sat heavy on the floor, cutlasses and axes gleamed. Gingerly I ran my finger along the cutting edge of a cutlass, imagining the heroic purposes such weapons might be put to – Grandpa Harmony battling boarders from a British man-of-war, or Great Uncle Noah fighting off hordes of pirates in the Sunda Straits, before succumbing to their poisoned darts -- while a few feet away a salesman spieled on to a customer about the latest model of bilge pump. The chandlery was a world that I could glimpse close up yet always from a distance, a world that my grandfather had exposed me to early with robustious tales of battles and pirates and typhoons, a world that beckoned and enticed me but in the end shut me out; it was and wasn’t mine. In the office next door I told a clerk I wanted to see my uncle. Just what his business was, aside from the chandlery, I couldn’t be sure; I knew he was a shipper of goods and a shipowner, but precisely what he shipped or owned escaped me, since he kept pretty mum about it. Around me in the front office were crates and bins offering samples of goods; in back, clerks perched on high stools penned entries into ledgers ata counter. “Good morning, Cousin Chris. We haven’t seen you down here for quite a while.” It was Cousin Dwight, Uncle Jake’s older son, tall, heavyset, with a wisp of waxed mustache curled over his lip like a snake: for a Harmony, a bit of a dandy. But a hero, too: in Mobile Bay the ironclad Tecumsehhad been blown to bits out from under him, leaving him splashing about in the water, one of the few survivors, with shots whizzing and booming all around -- an incident that, as he told it, prompted Admiral Farragut’s famous cry: “Damn the torpedoes – full steam ahead!” “Good morning, Dwight. I was hoping to see your father.” “He’s with a customer. Is there anything I can do for you?” “Thanks, not really. I need to see Uncle Jake.” “So how’s the scholar? Learning all kinds of things, I’m sure.” (A touch of irony; Dwight hadn’t been to college, didn’t miss it.) “Well, classes are suspended for the summer.” “Just lolling around, then?” “Not really. Ma has me sorting out Pa’s old papers in his desk.” “Anything interesting?” “Old bills long since paid, sewing machine announcements, hotel brochures from 1863. He never threw anything away.” “I see. Pa will be with you shortly, I’m sure.” Dwight retired into a back office, probably miffed because I wouldn’t deal with him. We’d never got on. I found him pushy and aggressive; he thought me soft. Suddenly Uncle Jake’s voice thundered forth from his back office. “If they think that, they can kiss my royal ass. My terms are clear; I won’t renegotiate. If that’s not good enough, the deal is off – do you hear? – off! I don’t need those shit-their-britches, and you can tell them that from me. Go to hell, all of you! Good day!” His voice had boomed; the whole room heard. The clerks didn’t even look up, just kept on pushing their pens. Then a silk-hatted older man came out of Uncle Jake’s office, a troubled look on his face, and hurried off. Uncle Jake stepped into the outer office in shirt sleeves, his eyes flashing under heavy brows, his face as red as his square-cut beard. When he saw me, his features softened. “Chris, boy, how are you? Come in, come in.” He waved me into his office. I took off my silk hat with the band of crape; we sat. Over his desk hung a large print of the clipper ship Falcon, which on its first run in the early fifties had made record time to California and been hailed by all as a wonder; part owner, he never let anyone forget it. He struck me as a hard man, as hard and keen as the cutlass I’d just touched in his chandlery. “Pardon my Dutch, Chris; I was a bit het up. You’re how old now?” “Twenty, sir.” “Old enough to have heard talk like that before. Men at sea, with no women around, talk like that too much. Not that you’ve been to sea or ever will be, unless of course you’ve changed your mind.” “Uncle Jake, I’m not meant for the sea.” “True enough: too thin, too slight. Not your fault, but once out of the harbor, you’d heave your cookies in the deep.” Years before, when Grandpa Harmony had taken all the kids in a small boat to see the lighthouse at Sandy Hook, I’d retched over the side all the way. Dwight of course told his father, and the two of them had been reminding me of it ever since. “Be that as it may,” said Jake, “don’t mention my cussing to your ma. It might make for rowdy weather between us.” “I won’t, sir. I promise.” “How is she, by the way? Haven’t seen her since the funeral.” “She’s getting used to Pa’s not being around, but it’s tough for all of us. She’s putting up a thumping big monument in Woodlawn, and lights candles in front of his daguerreotype, talks to him sometimes, prays a lot.” “Like me, when I lost Emmie. Didn’t pray much, but I talked to her at first.” Uncle Jake had lost his wife several years back. Suddenly his eyes cut into mine. “So, Chris, what can I do for you?” “First of all, sir, Ma wants to invite you and Dwight to dinner next Sunday, if you’re free. She’s still in deep mourning but is willing to see family.” “I should think so. Moping around won’t bring Mark back. Tell her Dwight and I will be delighted to come. Maybe about three?” “Three would be fine, sir.” “Chris, your pa and I had our differences at times, but Mark Harmony was a decent man. Too decent for his own good.” “Yes sir. Ma asked me to clean out his desk. Right off I found a diary. The very last entry in it, written the day before he died, thanked the Lord that he’d been able to see his family through the financial convulsion of the last decade and the tribulations of this one. ‘In spite of earlier doubts and fierce misgivings,’ he wrote, ‘thank God for the Venture.’ We can’t figure out what he meant. Would you have any idea, Uncle Jake?” His features tightened ever so slightly, and he looked away. “The ‘Venture’?” “Yes sir, with a capital V. We think it might have been some stroke of business he pulled off just before the war. He’d lost a deal of money, but after that everything was fine.” “I’m afraid I can’t help you, Chris. I know nothing about any ‘Venture.’ That’s old stuff. Does it matter?” “Well, it might help me with the family history I’d like to do someday. With classes over for the summer, I thought I might get started, maybe go through the stuff in Grandpa’s chest.” “Chest? What chest?” “The sea chest with all Grandpa’s papers. It came to us when he died, and it’s been sitting in the library ever since. Pa meant to sort it out but never did.” “Chris, I should have been told about that chest. Old Biggs was Caleb Harmony’s executor, but Biggs left it to me to go through my father’s personal effects.” “Ma told you about it at the time. You shrugged it off, said you were busy.” “I was, and then I guess it slipped my mind. I’d like to have a look at it.” “I’ll tell Ma, sir. Maybe when you come next Sunday.” “To really look into it, I’d need to take possession.” He was fingering a gold penknife; something was up. “Well sir, I’d kind of like to hold on to it. For the family history, you know. I really mean to write it.” “Chris, this family doesn’t need a scribbler; we’re doers. Forget the history. Don’t look back – that’s dead. Always look ahead!” “But Uncle Jake, the Harmonys have been everywhere, done everything. It’s a roaring good story, it’s prime. If it isn’t recorded, it’ll soon be forgotten. That’s where I come in. I’ll make sure the Harmony name lives on. Because you’re heroes, all of you, and you ought to be remembered!” (This was laying it on pretty thick, but with Jake you just about had to.) “Chris, life at sea isn’t all glorious adventure. It’s hard, it can twist your gut. It’s ugly sometimes, and sometimes just plain boring.” “Then tell me, Uncle Jake. I’ll put that in, too.” “No you won’t!” He slammed his fist hard on his desk. Papers flew; the Falcon hung crooked on the wall. Then, calmer: “For God’s sake, Chris, don’t mess with things you know nothing about.” “Well, sir, I still think you’re all heroes. Even Rick. How is he, by the way?” Asking about his younger son always put Uncle Jake off. Rick was a bit of a scamp, going off to dubious exploits at sea and then turning up when least expected, spouting tales of adventure and woe. “How should I know, Chris? I’m only his father. He’s been gone a year and a half without word. He could be drowned or in Timbuctoo.” A hint of regret? I couldn’t tell. Then suddenly he eyed me cannily, spoke softly. “You’re a shrewd little bastard, aren’t you? I hadn’t realized.” I smiled. “Just curious, Uncle Jake. Rick is family. I like to keep up.” He rose quickly from his desk. “See you next Sunday, Chris. Dwight and I will be delighted.” We shook hands. He was barking orders at a clerk as I left.

When I got back to our brownstone on St. Mark’s Place, Ma called me and my sister Sal into the sitting room. Sal was my twin, a brisk brunette with eyes of green agate. She and I shared everything, could often read each other’s thoughts, which was sometimes fun and sometimes just a mite awkward, since there are things a fellow’s sister doesn’t need to know. “I’ve been reading your father’s diary,” said Ma. “There are two entries you might find of interest, since they have to do with a ‘Venture.’ Here they are.” She cleared her throat, read. “16 October 1858. Another row with Jake over the Venture. He’s not telling me enough. What have I got into? He assures me all is well, substantial Profits will result. How? From what? A Mistake from beginning to end, but I’m committed, it’s too late to pull out.” She showed us the entry, paused to let us absorb it, then took back the diary, flipped through some pages, resumed. “9 August 1859. Good Profit from the Venture; Jake has settled the Accounts. He promises even more Profits, but I insisted that I want my share now and won’t be involved in any further Transactions. I’m out of it, thank the Merciful Lord, and will have no further Dealings with Jake.” Again, she showed us the entry and waited while we absorbed it. “Your father was not a happy man. I had no idea. I’ll inform you, if I encounter any more entries that seem relevant.” With that, she left us. That was Ma’s way: quiet, dignified, using few words, but when she spoke, you listened. We pondered in silence for a moment, then I told Sal about my meeting with Uncle Jake. “So Uncle Jake was in some ‘Venture’ with Pa, as we just learned from the diary, but now he won’t admit it.” “Exactly.” “So he’s a liar. And he wants to take possession of the chest.” She scrunched up her features in a frown. “Mr. Biggs asked him to sort out Grandpa’s personal effects.” “Will Ma let him have it?” “She might be glad to get rid of it.” The chest had been dumped on us when Grandpa died and had been sitting in a dark corner of the library ever since. Ma wanted to store it in the attic, but Pa clung to it, promising to sort through the contents, which of course he never did. In desperation Ma covered it with an old shawl and a burnt china mug, and we all forgot about it; it had hunkered down in the shadows. “Look,” said Sal, “you’ll need it for that family history you’ve been threatening to write.” “That’s what I told Uncle Jake, but he said forget about it, always look ahead, never back. Grandpa Harmony told me once that I was much too young for such a hefty undertaking, and Pa just plain damped me down, ordering me to stick to my studies.” “So nobody in the family wants you to write that history. Yet it’s a dandy story, it’s keen.” “That’s what I told Uncle Jake. We owe it to the family, the city, and the nation.” “Why doesn’t he see it that way? And why does he want to get his paws on that chest?” “There must be something in it he doesn’t want us to know about.” “Then it’s high time we had a look in there ourselves.” “Pa told me not to mess with it until I got my degree.” “Oh rats! We’re going to have a look right now!” That said, she hustled me into the library, whisked off the scarf and the mug, and with me helping, and the hinges creaking, opened the musty old chest. Loose papers spilled out amid a smell of dried ink and decay.

2

“What do you make of it?” asked Sal. Snatching up loose papers from the chest at random, we’d been reading in silence for at least twenty minutes. “It’s what in pidgin English is called a chow-chow,” I explained, having picked up the term in my readings. “A mix of stuff, a muddle. Loose pages from journals and letters, bills of lading, lists of port expenses, ships’ manifests. Grandpa must have tossed it all in the trunk and forgotten about it. But it’s super. For a historian” – so I now termed myself – “a devilish hot smash of a find!” “Look at this,” said Sal, thrusting at me a sheet of paper yellowed with age.

Rec’d from brig Resolute, J. Hawkins, master, 1 hogshead fine French brandy adressed to Harmony & Biggs, New York, containing preserved remains of Noah Harmony, deseased of Panama fever, Chagres, 11 Sept. 1823, age 31 yrs, 5 mos., 3 days, recovered from sea by said brig off Barnegat Light, having presumably washed overbord from another vessel, identity unknown, and now duly delivered hear for Christian burial, God’s will be done. Caleb Harmony, 16 Oct. 1823.

Sal looked perplexed. “So Great-Uncle Noah was shipped home in a hogshead of brandy that was lost at sea and then recovered and delivered as addressed?” “I guess. Quite a postmortem adventure!” “I thought he died fighting pirates in the Sunda Straits.” “So did I.” “Grandpa said his ship was becalmed, and suddenly thirty whatchamacallits -- ” “Thirty proas.” “ – attacked from all sides. He died a hero fighting pirates.” “A pistol in one hand, a cutlass in the other.” “And not from some silly old yellow fever.” “Killed the pirate chief with his last breath, and was buried at sea with full honors.” “So do you believe it now, or not?” “Well, Pa warned me more than once to take Grandpa’s stories cum grano salis.” “Please, no Latin.” “With a grain of salt.” “Grandpa lied?” “Pa didn’t quite say that. He said Grandpa liked to spin a good yarn.” Sal frowned. “You mean like those silly dime novels you used to read?” “I outgrew them long ago. This is something else again.” “And these,” she said, brandishing a loose page covered with a neat, tight hand. “Aren’t these journal entries from when Grandpa was rounding Cape Horn? They aren’t just a yarn too, are they?”

July 4. Terrible gale to westward; no thot of celebration. Mountinous seas, violent hale and snow skwalls. Strange hissing and singing sounds heard in the roar of the wind, abundant wild fowl, monstrous whales. One man overbord, reskew impossible; may the Good Lord receeve him in his Grace. Crew stedfast, passengers terrified. I prey to God we find good wether soon. Little progress. Lat. 56o 20’ S., long. 65o27’ W.

I glanced at the page she was holding. “No, those entries are solid, they’re for real. He always said that rounding the cape was the toughest sailing he’d ever known.” “Snow and ice in July?” “In the southern hemisphere it’s winter when we have summer.” “Oh.” “That was early in his career; I can tell.” “How?” “His handwriting is still quite legible. Later it became a god-awful scrawl.” My first job one summer had been as office boy at the Mariners’ Bank, where Grandpa had become president. They hired me because I alone could decipher his script. “But the stuff that really gets me,” said Sal, “is Grandpa’s letters to Grandma about the China trade. This one, for instance.”

When our ship rounded a bend in the river, I was thrilled to see a long line of vessels ankored side by side, perhaps a hundred of them, each flying its national flag. This is Whampoa, the port of Canton. Proceding upriver in a small boat, I marveled at the thik swarm of craft -- clumsy-looking oceangoing junks with sharp prows painted with huge eyes to watch for the devils of the deep, river junks manned by near naked koolies pulling on long sweeps, and mandarin patrol boats with red sashes around the muzles of their cannon. As we approached the confined district outside the city where, by the grace of the Son of Heaven, forin devils are allowed to reside and trade, we picked our way thru a hord of sampans with barbers, juglers and storytellers drifting past us, and pedlers hawking bird cages, and wives cooking over open fires on the stern while hens and ducks in wikker baskets clucked and skwawked insessantly. It was a feast of life, my dear Sarah, a mix of sites, sounds and smells like I have never encountered in all my roavings on the far seven seas.

Sal read it over twice. “Yes, that must have been a bang-up sight to see.” “There’ll be more,” I said. “We’ve just scratched the surface. But so far, nothing about any ‘Venture,’ and nothing for Uncle Jake to get worked up about.” “That letter congratulating Grandpa on becoming president of the bank, what’s that all about?” She showed me yet another loose paper.

Dear Caleb, Well, you old dog, you have survived storms and earthquakes and Chinamen and British men-o’-war to get yourself into the Chamber of Commerce, and now, to further dazzle the lubbers, you strut in clean cuffs and glossy patent leathers as the president of a bank. Congrats, old salt. Needless to say, I am devoured by envy, hence this hurried hodgepodge of a letter. Ah, Caleb, if you can holystone yourself, you sly Presbyterian, so can I. Gideon of old I shall no longer be. I shall trade my sea togs for finery, put on the sheen of Virtue, and tread its narrow Lane. You have sprigs, and sprigs of sprigs, as do I. For their sake – and our own – we must shed our naughty ways. Rechristened, I shall strut not a prince, but a king. Embrace me, fellow royal. Cleansed of our past, we

I put the letter down. “From some old pal of his, I guess. The rest of it is missing.” “He makes it sound like Grandpa had to become respectable. Wasn’t he always?” “Maybe not in the eyes of bluebloods. He smelled too much of the waterfront. Once he became a shipowner, that changed.” “I still don’t get it. The whole letter, I mean.” “Neither do I: a mysterium immensum.” “In English, please.” “A big mystery. But ‘sprigs of sprigs,’ that’s us.” “Us?” “His grandchildren.” “Oh. And in the letter of his to someone about supplies – a copy by a clerk, I suppose – why does he put ‘rum’ and ‘hats’ and ‘soap’ in quotation marks?” “I hadn’t noticed.” She showed me the letter; the first part was missing.

20 “rum” casks, 50 lbs lumber, 1 crate “hats,” 3 boxes “soap.” Daily exercise and song are highly recommended; an upturned kettle can serve as a drum. Also recommended is a familiar diet of rice, pepper, palm oil, potatoes, and corn. Beware of diseases of a febrile character and the flux. Allow substantial sums for gratuities, and at all times have on hand the two sets of papers. I wish you Godspeed; the prospects are bright. -- C. Harmony

I read it again, twice. “Yes, quote marks. But why?” “It’s like saying, ‘I don’t really mean these things; they stand for something else.’ ” “They’re code words?” “Exactly. There was something he couldn’t just say right out.” “But what?” “We’ll have to find out. Maybe this is what Jake’s worried about.” “Maybe. And maybe you’ve been reading too many novels.” “Grandpa’s papers are better than any novel. Misspellings and all, they’re real, they’re the Harmonys, they’re us.” That said, she scooped up more papers and resumed reading. I did, too, and started sorting them into piles. In time, I hoped, we’d gather together all the scattered pages of the letters and journals, and then organize them in chronological order. Meanwhile it was a rich, haphazard feast. We read until dinner, when Ma’s entreaties pulled us away from the chest. After dinner we went back to it and read until bedtime. “So?” said Sal finally, with a yawn. “It’s juicy, it’s prime. But the more I read, the less I understand.” “Me, too. There’s always something implied, something not spelled out.” “Fascinating. But let’s not get carried away.”

A ship with reefed sails and VENTURE on its bow, foundering in mountainous seas where whales broach and plunge, with sheets of gray water flying over it, its masts and decks coated with ice. Sinking in a squall, it becomes a junk with huge eyes on its prow, its cannon ringed with red sashes, while clucking hens strut on the deck. Nearby, rising silently out of a floating hogshead, Noah Harmony looms, wasted and delirious, his clothes stained with bloody black vomit, his skin a sickly yellow, as slowly, accusingly, he points the skinniest of fingers: Why do you disturb me? Why?

I woke up in a sweat.

3

“Pa, were you a cabin boy at fifteen?” “No, at sixteen.” “A ship’s master at twenty?” “More like twenty-two. So long ago. Why do you ask?” “Just wondering.” “You’ve been listening to Grandpa, haven’t you? The so-called family motto: cabin boy at fifteen, ship’s master at twenty.” “Well … yes.” “Don’t worry about it, Chris. Not everyone is meant for the sea. I wasn’t.” “But you went to sea for quite a spell, didn’t you?” “Six years. That was my youth, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. But then I’d had enough. I wanted to come ashore, snug down, get married. And I did.” “Uncle Jake didn’t, though, did he?” “He got married, but he didn’t quit the sea. Not for a long, long time. It was in his blood.” “He sure is Go Ahead, isn’t he? A real wide-awake, a hustler.” “Yes, Chris, he’s all that and more.” “Like Grandpa.” “But Grandpa has a mellow side, too; Jake doesn’t. Oh, Jake can be charming, all right, but at heart he’s a mean, hard man. Keep smooth weather between you; you wouldn’t want him for an enemy.” “No sir.” “You wouldn’t want that at all. And there’s a difference between his side of the family and ours. They have adventures and tell tall tales, but don’t believe everything they say. We live quieter; we have the burden of truth. Remember that, Chris. It’s important.” “Yes, Pa. The burden of truth.” “Let that be your ballast, your anchor. In the long run it’ll keep you safe.”

Uncle Jake and Dwight came to dinner by carriage, which Ma considered just a bit flash, since we didn’t keep one. They had a hint of pomade in their hair, and both sported gold cuff links and a diamond tiepin. Ma used our best dishes, a set of blue-and-white chinaware that Grandpa had brought back from Canton long ago. Jake and Dwight raved about Ma’s roast turkey, which Jake carved with a flourish, eyes flashing, announcing, “The nearer the bone, the sweeter the meat!” They ate with gusto, pronouncing Ma’s turnips and spuds delicious and her plum cake “confoundedly good.” Ma’s cooking was super, but I thought their praise just a bit much. Throughout dinner, and afterward in the parlor as well, they regaled us with stories, Dwight telling about running the Vicksburg batteries with Farragut and his fleet in ’62, and Jake relating how years before on the brig Hunter, bringing palm oil and ivory from the Guinea coast, he took command when the captain and mates were stricken with fever, and sold the cargo for a roaring good price in New York. “You know how I never come down with fever, not in Africa or in the Americas either? I took the advice of a Spanish gent who’d been in those parts many a time: soak your feet in brandy, wear thick wool socks, avoid night air and the noonday sun. Other poor devils took sick, turned yellow, and wasted away, but I was in fine fettle.” Finally he sent Dwight to fetch their carriage; a look passed between them. Then, to end the evening with a bang, he entertained us with a host of anecdotes about old merchants and skippers he had known. This was Uncle Jake at his best. He had us laughing one minute, and shocked or all but in tears the next. Yet as he talked, he kept fingering his gold penknife, which struck me as odd. When he launched into yet another yarn about a sailmaker who married three ladies of property – albeit one at a time – and had even Ma, who was kind of straitlaced, laughing to the point of tears, Sal slipped quietly out of the room. Moments later we heard her shout, “Chris, they’re stealing the chest!” I was on my feet in a flash. Darting into the hallway, I found Dwight and Uncle Jake’s black coachman Luke lugging Grandpa’s heavy chest toward the open front door, while Sal shouted and protested. Making a flying leap, I landed on the chest, which under my weight crashed to the floor. Luke stepped back in astonishment, but as Sal and I yelled “Thief!” at the top of our lungs, Dwight’s look of surprise changed to rage. Lunging, he pummeled me with his fists. I tried to hit back, couldn’t, so I huddled up and fended off his punches as best I could, while still yelling “Thief! Thief! Thief!” By the time our cries brought Ma and Uncle Jake from the parlor, and the cook and the maid from the kitchen, my face was bloodied up and pretty much of a mess. “Stop it, Dwight!” yelled Jake. Dwight stepped back, breathing hard, scowling. “Thief!” I cried, pointing at Dwight. I was sitting crumpled on the floor, one eye shut, nose bleeding. “Sal,” said Ma, “fetch a wet towel and help your brother stop the bleeding. Annie and Meg, get back to the kitchen. Dwight and Jacob, what’s this all about?” The servants left. Dwight started to speak, but his father cut him off. “Martha, I was only taking what’s rightfully mine; I didn’t think you’d care. But Dwight’s too free with his fists; I’ll deal with him later.” “Jacob, that chest isn’t yours.” “I’d be doing you a favor to take it off your hands. What do you want with all those old papers?” “More to the point, Jacob, what do you want with them?” “Just a matter of winding up some loose ends from Pa’s estate. Dull legal stuff. Those papers may or may not be relevant.” Ma eyed him something fierce. “The chest stays here. Put it back where you found it.” Jake’s features tightened, but at a nod from him Dwight and the coachman lugged the chest back into the library. “And now, Jacob, you and your minions can leave.” She said “minions” with a sting of contempt. “That chest is mine, Martha, and I mean to have it.” “Jacob, you are not a gentleman.” “Martha, I never said I was. But thanks for the dinner. I hope you’ll make it into half mourning soon; Mark would approve. When you do, I’ll welcome you back to the land of the living.” Preceded by his “minions,” he flashed a sour smile and left. Sal came with a wet towel and dabbed my face; I was surprised by the splotches of blood on the towel: roses, a whole bouquet. Then she ran to a front window, looked out. “They’re going,” she reported. “They’re gone.” “Did they put the chest back exactly where they found it?” asked Ma. Sal ran to the library, looked. “Yes, Ma, they did.” “And that’s where it shall stay. Christopher, I advise you to take up boxing; I don’t think Dwight is done with you. As for the chest, the two of you must go on searching it. Jacob’s worried about something; find out what it is.” “Yes, Ma,” we chorused. “Sal, put some salve on your brother’s wounds. Annie and Meg will see to the dishes. I’m going to bed. I suggest that you two do the same.” Of course we didn’t. “Dwight really hates you,” said Sal, as she put on the salve. My bleeding had stopped, but the sight in one eye was a blur. “I guess he does. I didn’t know it until today.” “Me neither.” “But why? I’ve never done him hurt.” “He’s jealous, because you were Grandpa’s favorite.” “I wasn’t! He liked all of us.” “Dwight was the oldest, biggest, strongest, and fastest, and we all knew it, but Grandpa liked you best.” “Why?” “You were the youngest of the boys, not as big and strong as the others. You had a wonderful smile, an even temper, and you loved to hear his stories.” “We all did.” “Yes, but as Dwight got older, he got bored with them, he fidgeted. He didn’t want to hear any more about Grandpa’s adventures; he wanted to get out and have adventures of his own." “He did. Look at all he went through in the war.” “But he’s still jealous. Take Ma’s advice, learn to box. I’d love to see you punch him in the face.” “So would I.” “Chris, you’re a hero. The way you jumped right on that chest!” “I feel like mush.” “You’re a hero.” “And I’ve never been in a war.” “You’re in one now!”

* * *

Dark Knowledge is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Signed copies are available from the author; contact him at his e-mail address: cliffbrowder@verizon.net.

* * *

Coming soon: Symbols of Hate. Should those objectionable statues -- objectionable to some -- come down? Is Columbus a hero or a sponsor of genocide? And why did I hate Teddy Roosevelt?

© 2018 Clifford Browder

Published on January 24, 2018 04:49

January 21, 2018

338. New York and the Slave Trade

Dark Knowledge, the third title in my Metropolis series of novels set in nineteenth-century New York, was released by Anaphora Literary Press on January 5, 2018, making it available from

Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Signed copies are available from the author. The post below was inspired by the research I did for the book, using primary sources whenever possible. For more about this and other works of mine, see below following the post.

SMALL TALK

Every writer who gets published learns quickly the joys and horrors of exposure, when reviews begin to come in. Here are two LibraryThing pre-publication reviews of my novel Dark Knowledge, showing the difference in readers’ reactions to the same work. The first is a one-star review, the worst that any work of mine has ever received; the second is one of several four-star reviews. Ratings range from one star, the worst, to five stars, the best; four stars is very good, but not quite a rave. To give five stars, the reviewer has to be vaulted into realms of unmitigated bliss.

I've tried, but I just can't get into this book. The plot is thin and convoluted; lots of useless details that I'm having a hard time keeping straight and threading together into a story. The characters are shallow and unsympathetic. (✪)

I'm interested in what a thoroughly enjoyable read this was, given that transport of slaves was central to the story. Browder managed to touch me with complicity without making me uncomfortable. The trials and successes of a budding historian finding out about his family's part in in slave trade were used to tell a lively and entertaining tale. The writing styles, plot, pace and character development were excellent. I received this as a LibraryThing Early Review copy. Thank you. (✪✪✪✪)

NEW YORK AND THE SLAVE TRADE

By the mid-nineteenth century the port of New York was the busiest in the hemisphere, doing trade with all the major ports in the world. That New York City was also the center of the illegal slave trade in the 1850s may surprise many today, but such was the case. Respectable citizens were hardly aware of the trade, but those on the waterfront, even if uninvolved, could see signs of it. Any vessel bound for Africa was suspect. During eighteen months of the years 1859-60, eighty-five slavers were reported to have been fitted out in New York harbor, transporting from 30,000 to 60,000 slaves annually. This post will have a look at that trade, drawing mostly on primary sources.

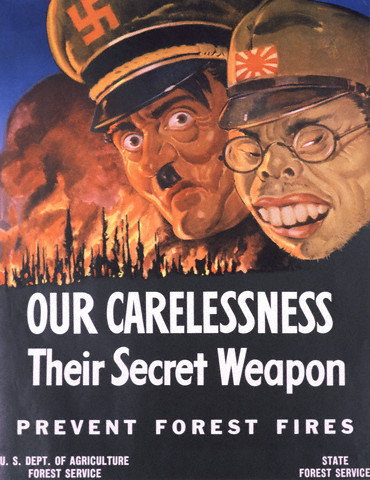

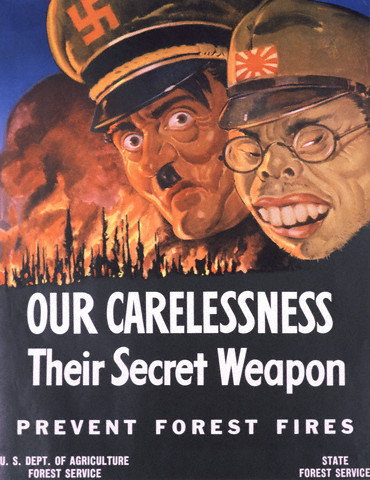

Ships used in the slave trade: schooner (left), brig (center), and bark (right). Small, fast ships that

Ships used in the slave trade: schooner (left), brig (center), and bark (right). Small, fast ships thatcould outrun British cruisers were preferred.

BPL

In June of 1860 – on the very eve of the Civil War – a young New Englander named Edward Manning, being short of cash, went to a New York City shipping office and signed up for three years on the Thomas Watson, a whaler being fitted out in New London, Connecticut. Going to New London, he found a smart-looking vessel of 400 tons, remarkably clean for a whaler, many of whose crew were, like himself, “greenies.” A fine-looking woman came aboard and conferred with the captain in his cabin; she was said to be one of the owners. Had he not been a greenhorn, young Manning might have wondered why the ship was taking on so much rice, hard tack, beef, pork, casks of fresh water, and other supplies – far more than was needed for the crew of a whaler – as well as quantities of pine flooring that would be laid over the stores in the hold so as to create a new deck. He might also have wondered why the ship couldn’t get clearance and sail from New London, but instead went down to New York, accompanied all the way by a U.S. revenue cutter, all of which suggested that the ship was somehow suspect and might have a history. In New York the Thomas Watson anchored briefly off the Battery, then caught a favorable breeze and sailed from there, presumably bound for waters rich in whales.

As the vessel crossed the North Atlantic, it proved to be a smart sailer, hard to overtake. Nearing the presumed whaling grounds, the captain posted a lookout aloft to look out for “blows,” and even sent out boats in quest of whales, sustaining the image of a whaler all the way to the coast of Africa. Approaching that coast, it sighted a British man-of-war, at which point the “old man,” as the crew referred to the skipper, ordered the men to remove the pine flooring and store it aft. As the warship approached, it fired a shot across the whaler’s bow, raising a splash. “What ship is that?” came the query. “The Thomas Watson.” “I’ll board you!” So spoke the greatest navy in the world, displaying the arrogance typical of a world power. By now the greenies had long since grasped the fact – not particularly dismaying to most of them – that the Thomas Watson was no whaler but a slaver in disguise, hoping now to outwit the British Navy, which was intent on suppressing the slave trade, illegal in most parts of the world. A gig came alongside, and the English commander boarded the vessel, conferred with the captain in his cabin, and then inspected the deck and hold. Though he found no overt signs of a slaver, he was frankly skeptical and promised to have a look at the vessel again in the future. Once the departing visitors were out of earshot, the captain, an irascible man, exclaimed, “You English sucker! You’ll see me again, will you? I’ll show you!” In point of fact, they never encountered the warship again.

HMS Black Joke firing on the Spanish slaver El Almirante. The British ship freed 466 slaves.

HMS Black Joke firing on the Spanish slaver El Almirante. The British ship freed 466 slaves.If the greenies had any reservations about serving on a slaver, they had little choice, being far from home and near the coast of Africa. Enhancing their resignation may have been the realization that no trade on the seas was more lucrative than this one, which might mean more pay at the end of the run, if the British Navy -- and the American, though it was typically less in evidence – could be eluded. In 1860 the trade still flourished, taking slaves from West Africa to Cuba, then a Spanish colony, where the authorities looked the other way while the planters acquired more labor for their sugar plantations and paid well for it. Of the whole crew, only Manning voiced objections to serving on a slaver, for which he earned the captain’s undying enmity.

As the Thomas Watson neared the African shore, a small boat with naked black rowers approached, waving a bright red rag. A Spaniard came on board, embraced the captain, and kissed him. They conferred, then the Spaniard departed, leaving the crew mystified as to what this was all about. The Spaniard was allegedly a palm oil merchant, but the mystery remained.

For two weeks the Thomas Watson cruised about, not too far from the African coast, maintaining the feeble pretense of whaling. Then they approached an uninhabited stretch of shoreline, where only a long, low shed was visible – a barracoon (slave barracks) -- as he later learned. The captain, showing signs of nervousness, posted the mate aloft with a spyglass, ordering him to report any ship in sight. “Sail ho!” the mate finally cried out. “Where away?” asked the captain. “Right ahead, and close to the beach.”

They now made contact with a schooner, and the palm oil merchant reappeared, boarded the ship, and gave the captain another affectionate kiss. The pine flooring was now quickly laid, creating a deck to receive the oncoming cargo. Naked blacks – men, women, and children – now issued from the shed and walked in single file to the beach, where their black guards began tossing them into a surf boat that then negotiated the surf safely and transferred its human cargo to a small boat from the ship. The slaves were then taken to the ship and piled into the hold, the women separately in steerage. The ship was rolling all this while, so the slaves were seasick, and the foul air and great heat made the hold unbearable. Five or six were dead by morning, and their bodies were tossed overboard.

Model of a slave ship. The slaves are packed in on a deck laid over the stores in the hold,

Model of a slave ship. The slaves are packed in on a deck laid over the stores in the hold,which include ivory tusks. This vessel is armed, but most slavers relied on speed to escape

pursuing warships.

Kenneth Lu

Having secured its cargo, the Thomas Watson immediately weighed anchor and got under way, carrying some eight hundred blacks of all sizes and ages, with the Spanish captain and a crew of eighteen whites. The Spaniard, a veteran of the trade, was now in charge, whip in hand, and his ferocious manner kept the slaves in check. Guarded by overbearing guards of their own race, whom Manning identified as Kroomen (an African people living in Liberia and the Ivory Coast), the slaves were brought up on deck and fed rice and sea biscuits, but the stench below was suffocating, until means were found to let air in for ventilation. The Spaniard was a man of moods and contradictions. He delighted to let the little girls come up and play on deck, but when a man was caught stealing water, he had him flogged unmercifully. And yet, having some knowledge of medicine, he improvised a hospital on deck and treated those who were ill, probably saving the lives of several. Dysentery was the commonest ailment, but there were two fatal cases of smallpox, one of scurvy and one of palsy. Also, one woman gave birth to twins, but both infants died.

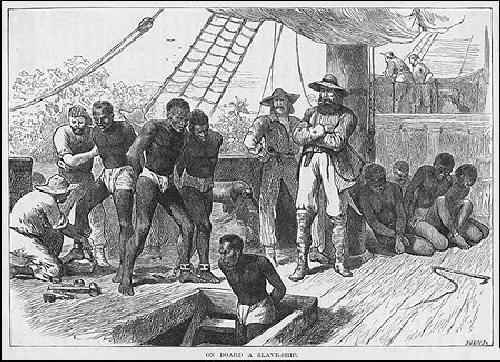

Slaves on deck, being shackled.

Slaves on deck, being shackled.The long transatlantic trip was not pleasant even for the whites on board. Scared out of the hold, the ship’s rats invaded the forecastle, where the crew slept. Manning tells how one night he felt sharp claws on his face, and a rat gnawing at his big toe, whose toenail was almost gone; after that he slept on the deck. When a crewman died of a fever in the dark, dingy hole of the forecastle, he was sewed up in canvas and laid out on a plank on deck; then, with no attempt at a service, the plank was raised at one end, and the body slid into the sea. Meanwhile the American captain was getting drunk daily on rum and then retiring to a spare boat on the poop deck to sleep it off. The Spanish captain remonstrated with him, protesting that he was setting a bad example for the crew, but to no avail.

The condition of the slaves was now of some consequence, as the vessel was approaching Cuba. They were brought up on deck in batches, and bathed in the spray from a hose. To fumigate the hold, the crew stuck red-hot irons into tin pots filled with tar, sealed the hold with hatches, and waited two hours; by then the hold was considered cleansed.

Having been at sea for six months, the crew were now eager to make land. The likable second mate expressed the hope that he would make enough money on this voyage to buy a little place ashore and settle down; for him, it was just a job. They now scraped the ship’s name off the stern, thus making them all outlaws, and the vessel fair game for anyone. Special precautions had to be taken, for British men-of-war patrolled the Cuban coast as well, and the appearance there of a whaler would arouse suspicion, especially if large numbers of blacks were seen on deck. In time they rendezvoused successfully with two schooners, one of which came alongside; brought up to the deck, the blacks were made to jump down to the schooner’s deck, the Kroomen going last. The Spanish captain too left the ship, and the second schooner took on half the blacks from the first one, after which the two schooners made for land. Their cargo delivered, the crew of the Thomas Watson then removed the telltale pine flooring and threw it overboard.

The ship now sailed to Campeche, Yucatan. Chloride of lime was sprinkled in the hold to eliminate the smell of slaves in confinement, but some hint of the odor remained. The crew were now paid, and paid well, in Spanish doubloons, and Edward Manning took passage on a Mexican schooner to New Orleans, where he arrived in January 1861. There, finding Secession in the air and the people feverish, the New Englander got out fast, returning to New York by rail. When war broke out, he joined the U.S. Navy and served for the duration. The Thomas Watson became a Confederate blockade runner but while pursued by Northern warships it ran aground on a reef off Charleston, South Carolina, and was burned by the Northern ships to the water’s edge.

Such was the account of Edward Manning, which he published with the title Six Months on a Slaver in 1879. Though opposed to slavery, he tells his story in a sober, matter-of-fact way, expressing sympathy for the slaves, but never inveighing against the evils of slavery. In short, he lets the story tell itself. The book is a rare example of a firsthand account of the trade, since those involved usually shunned publicity. The voyage was routine, with no drama: no pursuit by British cruisers, no slave revolt, no storm, no high death rate among the slaves. The vessel’s prompt departure from the port of New York, which Manning doesn’t explain, was probably facilitated by prior negotiations with the authorities there and smoothed with a bribe. Manning doesn’t identify the coast where the slaves were taken on, but it was certainly that part of West Africa where the Atlantic trade flourished: the Ivory Coast, the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), and the Slave Coast, this last being the coastal area of modern-day Togo, Benin, and western Nigeria.

The first meeting with the palm oil merchant, later identified as the Spanish captain, was to arrange a rendezvous for loading the slaves; this was to make sure that the loading would go quickly, so the vessel could get away fast from the coast without being caught by a British warship. The Spaniard was evidently a loose packer, meaning that he allowed the slaves ample room and thus kept mortalities to a minimum; tight packers usually had corpses to dispose of, and the corpses, once in the sea, drew sharks that might follow the ship for days: the sure sign of a slaver to the captain of a British cruiser. But in the vast expanse of the North Atlantic, there was little risk of detection, until the slaver approached the Cuban coast. The Kroomen guards were probably not destined for slavery, but further employment by the Spaniard on future voyages, it being a sad fact that blacks too participated in the trade and facilitated it.

“The Slave Trade in New York,” a January 1862 article in The Continental Monthly, a new periodical of the time published in New York and Boston, gives useful background for Manning’s story. Since by then reform was under way, the conditions described are those prevailing before the 1860 election: exactly the time when Manning was recruited for the Thomas Watson. According to the article, New York City was the world’s leading port for the slave trade, with Portland and Boston next. (The author might have added New Orleans.) Slave dealers, some of them seemingly respectable Knickerbockers, contributed liberally to political organizations and thus influenced elections not only in New York but also in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. The captains involved in the trade lived in residences and boardinghouses in the eastern wards of the city and formed a secret fraternity with signs, grips, and passwords. A slave captain planning a voyage would initiate preparations in a first-class hotel like the Astor House, where the risk of detection was less than in a private office. Runners, provided with the names of men of every nationality who had served on slavers before, would be sent to boardinghouses to recruit a crew; their appraisal of prospective crewmen was reliable, their blunders few. Rather than equipment for a whaling voyage, as in the case of the Thomas Watson, apparatus for refining pine oil, a common and legitimate import from Africa, was often used as a blind, for a U.S. marshal would inspect in port any vessel suspected of being a slaver. One yacht owner was quoted as saying that he had paid $10,000 to get clearance. But getting clearance at the custom house was easy, a transparent disguise being enough. And should a slaver be captured by a British warship, the New York owners were rarely troubled, having a corps of attorneys on retainer to defend them.

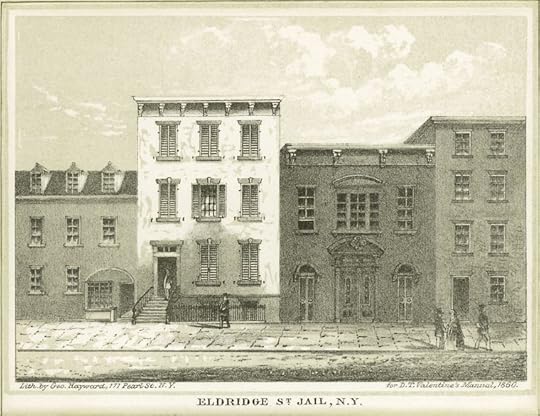

As an example of the laxity of the law, the article tells the story of the brig Cora, a slaver captured at sea and brought to New York. Her skipper, Captain Latham, was lodged in the Eldridge Street Jail, where inmates caroused freely with liquor and champagne. Securing funds from a Wall Street connection, Latham bribed one of the U.S. marshal’s assistants with $3,000 and so was allowed to leave the premises, buy a suit at Brooks Brothers, and proceed to the dock just in time to catch a steamer to Havana. Since then Latham was said to have returned to the city in disguise.

Not all slave voyages were as routine and uneventful as that of the Thomas Watson. Edward Manning never got ashore to see a caravan of slaves arrive from the interior. One such caravan of twelve hundred naked slaves, captured and guarded by other blacks, has been described as arriving at the coast to the sound of rifle fire, tom-toms, and drums. The trading that ensued might involve an exchange of slaves, ivory, gold dust, rice, cattle, skins, beeswax, wood, and honey for cotton cloth, gunpowder, rum, tobacco, cheap muskets, and assorted trinkets. A strong, healthy male of twenty might fetch three Spanish dollars; women and boys went for less.

A slave caravan.

A slave caravan.As a slaver weighed anchor laden with “black ivory,” heart-rending scenes might occur. On one occasion blacks in two canoes and on a raft came alongside a departing brig, begging to be taken also, so they could rejoin relatives now chained under the hatches. Seeing that they were old, the captain took only three. The others persisted, till a six-pound shot destroyed the raft. Some of the crew were troubled by this, but the captain remarked coolly, “Your uncle knows his business.”

And what became of the elderly and sick slaves that no trader wanted? On one occasion eight hundred of them were taken out in canoes by other blacks and sunk with stones about their necks. Here again, the cruelty of blacks on blacks matched that of whites on blacks. The slave trade corrupted all who were involved in it.

The worst that could happen at sea was not so much a slave revolt but a fire. One repentant skipper told of such a horror at night, when all their cargo was locked under hatches. The crew tried to put out the fire below with buckets of water, but the flames spread amidships and the vessel was doomed. “Bear away, lads!” ordered the skipper. “Lashings and spars for a raft, my hearties!” The crew improvised a raft from the masts and bowsprit, and hoisted out the two boats, while the fire smoldered between decks and the slaves screamed. As the crew abandoned ship, a merciful mate lifted the hatch gratings and flung down the shackle keys, so the slaves could escape from the hold. As the ship’s two boats towed the raft clear of the burning vessel, the slaves gained the deck, only to become enveloped in flames. Some jumped into the sea and tried to climb aboard the boats and raft; a few succeeded, but the crewmen, fearing that they would be swamped, fought most of them off with handspikes. As the white survivors distanced themselves from the vessel and the drowning slaves, the sea was illumined for miles by the flaming brig. Out of 640 slaves, 115 were saved on the raft. Saved, of course, for slavery. For the traders, not a very satisfactory voyage.

Did those who participated in the trade ever repent of it? Yes, but usually on their deathbed. Said one: “There is no way to stop the slave trade but by breaking up slaveholding. Whilst there is a market, there will always be traders. Men like me do its roughest work, but we are no worse than the Christian merchants whose money finds ships and freight, or the Christian planters who keep up the demand for negroes. May God forgive me for my crimes, and may my story serve some good purpose in the world I am leaving.”

And as Edward Manning’s account makes clear, slave trading was an equal opportunity operation. Even in those Victorian times, when ladies were confined to the parlor, with forays into the nursery and outings for good works, some seemingly respectable women were up to their ears in the trade. The woman Manning observed was a New London resident, but there were more such women in New York. They kept a low profile, but occasionally their name crept into print. A Law Intelligence report in the New York Tribune of September 22, 1862, told how a Mrs. Mary Jane Watson of 38 St. Mark’s Place had operated as a blind for John A. Machado, who skippered the bark Mary Francis on a run from Africa to Cuba. Machado was arrested in New York, but to my knowledge no woman was ever prosecuted for participation in the trade.

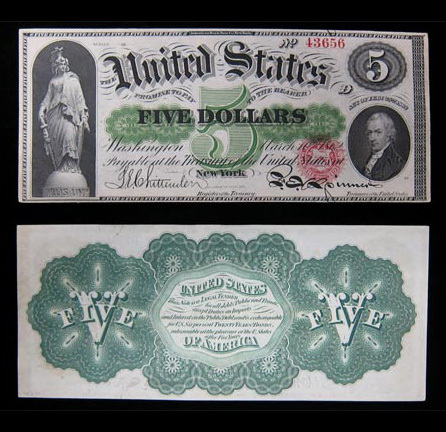

So good Christian men and women – ship owners, ship fitters, insurers, and provisioners, aided by banks extending loans to planters, and by iron merchants providing shackles and manacles – chose to get involved in this shameful web of complicity. Why? Two reasons: money and immunity. A healthy young slave costing $50 in Africa could easily bring $350 or even $500 in Havana, and a healthy but inferior slave at least $250. And the chances of getting caught and prosecuted were minimal. For some, the temptation was simply too great, especially when you could remain at a safe remove and leave the dirty work to others. So it went until Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, and the new Republican administration enforced the law banning the trade and ended it once and for all.

BROWDERBOOKS

All books are available online as indicated, or from the author.

1. No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World (Mill City Press, 2015). Winner of the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. All about anything and everything New York: alcoholics, abortionists, greenmarkets, Occupy Wall Street, the Gay Pride Parade, my mugging in Central Park, peyote visions, and an artist who made art of a blackened human toe. In her Reader Views review, Sheri Hoyte called it "a delightful treasure chest full of short stories about New York City."

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017.

Review

"If you want wonderful inside tales about New York, this is the book for you. Cliff Browder has a way with his writing that makes the city I lived in for 40 plus years come alive in a new and delightful way. A refreshing view on NYC that will not disappoint." Five-star Amazon customer review by Bill L.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

2. Bill Hope: His Story (Anaphora Literary Press, 2017), the second novel in the Metropolis series. New York City, 1870s: From his cell in the gloomy prison known as the Tombs, young Bill Hope spills out in a torrent of words the story of his career as a pickpocket and shoplifter; his brutal treatment at Sing Sing and escape from another prison in a coffin; his forays into brownstones and polite society; and his sojourn among the “loonies” in a madhouse, from which he emerges to face betrayal and death threats, and possible involvement in a murder. Driving him throughout is a fierce desire for better, a persistent and undying hope.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

Reviews

Reviews"A real yarn of a story about a lovable pickpocket who gets into trouble and has a great adventure. A must read." Five-star Amazon customer review by nicole w brown.

"This was a fun book. The main character seemed like a cross between Huck Finn and a Charles Dickens character. I would recommend this." Four-star LibraryThing review by stephvin.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

3. Dark Knowledge (Anaphora Literary Press, 2018), the third novel in the Metropolis series. Adult and young adult. A fast-moving historical novel about New York City and the slave trade, with the sights and sounds and smells of the waterfront.

The back cover summary:

The back cover summary:New York City, late 1860s. When young Chris Harmony learns that members of his family may have been involved in the illegal pre-Civil War slave trade, taking slaves from Africa to Cuba, he is appalled. Determined to learn the truth, he begins an investigation that takes him into a dingy waterfront saloon, musty old maritime records that yield startling secrets, and elegant brownstone parlors that may have been furnished by the trade. Since those once involved dread exposure, he meets denials and evasions, then threats, and a key witness is murdered. Chris has vivid fantasies of the suffering slaves on the ships and their savage revolts. How could seemingly respectable people be involved in so abhorrent a trade, and how did they avoid exposure? And what price must Chris pay to learn the painful truth and proclaim it?

Early reviews

"A lively and entertaining tale. The writing styles, plot, pace and character development were excellent." Four-star LibraryThing early review by BridgitDavis.

"At first the plot ... seemed a bit contrived, but I was soon swept up in the tale." Four-star LibraryThing early review by snash.

"I am glad that I have read this book as it goes into great detail and the presentation is amazing. The Author obviously knows his stuff." Four-star LibraryThing early review by Moiser20.

Just released; available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

4. The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), the first novel in the Metropolis series, tells the story of a respectably raised young man who chooses to become a male prostitute in late 1860s New York and falls in love with his most difficult client.

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, if you like, but no porn (I don't do porn). Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

Reviews

"At times amusing, gritty, heartfelt and a little sexy -- this would make a great summer read." Four-star Amazon customer review by BobW.

"Really more of a fantasy of a 19th century gay life than any kind of historical representation of the same." Three-star Goodreads review by Rachel.

"The detail Browder brings to this glimpse into history is only equaled by his writing of credible and interesting characters. Highly recommended." Five-star Goodreads review by Nan Hawthorne.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

An English map of the Gold Coast, Slave Coast, and Ivory Coast of West Africa, 1670.

An English map of the Gold Coast, Slave Coast, and Ivory Coast of West Africa, 1670.Coming soon: As a free sample, the first four chapters of Dark Knowledge. After that, Symbols of Hate: When should an objectionable statue be removed, and when should it stay? And after that, maybe Goldman Sachs again, the vampire squid of Wall Street.

© Clifford Browder 2018

Published on January 21, 2018 04:37

January 14, 2018

337. The Next Big Thing: Ten That Changed Us, Shook Us Up

Dark Knowledge, the third title in my Metropolis series of novels set in nineteenth-century New York, was released by Anaphora Literary Press on January 5, 2018, making it available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Signed copies are available from the author. For more about this and other works of mine, see below following the post.

A note to my friends: Yes, I publicize my books, because you have to, and this year there will be more. BUT: Don't buy them unless you really wish to read them. I don't want to be one of those writers whose friends say, "Oh my God, he's published another book! I suppose we'll have to buy it." Some of my friends buy all my books, some buy none, and some buy some but not others, and all of that is okay. In time, books usually find their audience.

SMALL TALK

Just after 7 a.m. the driver stopped his car on the lower level of the bridge, where there is no pedestrian walkway, only a maintenance catwalk and a barricade-height railing. He quickly climbed over the railing and jumped into space and his death. Later retrieved from the water far below, the body was identified as that of a 38-year-old man from Queens. This was the fifteenth suicide on the bridge for 2017, three more than in 2016, but three less than in 2015.

The bridge in question is the George Washington Bridge, spanning the Hudson River and joining Washington Heights, Manhattan, to Fort Lee, New Jersey: a magnificent double-decked suspension bridge dating from 1931 that I have walked many times on the upper level, a heavily trafficked span whose constant din of traffic has not kept me from gazing in awe at the towers soaring high above me and at the steel harp of the cables, or kept me from looking dizzily down into empty space and, far below, the waters of the Hudson, splashed on sunny days with dots or streaks of silver. Just looking down for a moment makes my legs go weak, so scary and yet fascinating is that vertiginous drop. And when I reach either end of the bridge and feel terra firma under me again, I always feel a bit of relief.

The George Washington Bridge rivals the Empire State Building, and the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, as a preferred site for suicide attempts. An attempt is thwarted on the bridge about every five days, for a total of 68 “saves” in 2017 as of November last. Port Authority officers train cameras on the pedestrian walkway, and if they see someone lingering too close to the railing for a bit too long, they can dispatch a fully equipped emergency unit to prevent the attempt. In addition to the 68 “saves,” 37 possible attempts were thwarted when officers, forewarned by someone, stopped the presumed suiciders before they even reached the bridge.

But officers can’t prevent every attempt, as the total of 15 suicides for 2017 attests, so a new preventive is being installed: an 11-foot-high fence connected to netting that forms a canopy over the pedestrian walkway. This is a much more formidable obstacle than the barricade-height railing already in place; to get past it would take time and effort, giving the officers more time to intervene. According to suicidologists (yes, there really is such a word, though my spell check doubts it), barriers on bridges are effective in reducing rates of death by suicide. So more power to the barriers, and if you ever take a walk across the bridge (which I highly recommend), just don’t linger long by the railing.

Source note: This article was inspired by an article by James Barron in the New York Times of December 30, 2017.

THE NEXT BIG THING

It bursts upon the scene. Fans want to attend it, consumers want to buy it, investors want to invest in it before word gets around. It excites, it maddens, it intoxicates. Above all, it is something startlingly new, astonishingly different. And it can make the world better … or worse.

No, don’t mean the entrepreneur-led charitable foundation of that name that seeks to empower young entrepreneurs to take on the world, admirable a goal as that is. Nor do I mean any number of novels and high-tech gadgets and other stuff marketed online as “the next big thing.” I mean a rich variety of break-through inventions, styles, fashions, and fads that swept New York and the nation, if not the world, changing, or seeming to change, the way we live. Let’s have a look at ten of them.

1. Fulton’s steamboat, 1807

In 1807 Robert Fulton’s pioneer North River Steamboat, later rechristened the Clermont, made the round trip on the Hudson River from New York to Albany and back in an amazing 32 hours. Amazing because, prior to this, the Hudson River sloops, sailing upstream against the current and often against wind and tide as well, took as much as three days just to get to Albany. Steamboats revolutionized traffic on the waterways of America and the world, bringing distant places closer together and, in New York State, letting New York City legislators get to the state capital expeditiously, so they could pursue their legislative schemes and stratagems, and try to keep upstate lawmakers, whom they termed “hayseeds,” from neglecting or abusing their beloved Babylon on the Hudson.

Steamboats on the Hudson at the Highlands. A Currier & Ives print of 1874.

Steamboats on the Hudson at the Highlands. A Currier & Ives print of 1874.2. Jenny Lind, 1850

The Castle Garden concert.Promoted shrewdly and outrageously by P. T. Barnum, the master of humbug, the Swedish coloratura became a sensation in America. Citizens who knew little or nothing about coloratura sopranos suddenly felt an intense need to hear the Swedish Nightingale warble her magical notes. Thousands thronged the piers to witness her arrival on September 1, some of them suffering bruises and bloody noses in the process; a fatal crush was narrowly avoided. To get her through the crowd, Barnum’s coachman had to clear the way with his whip. As for her first performance on September 11 at Castle Garden on the Battery, she astonished the packed audience with her vocal feats. All tickets having been sold already at auction, some without tickets hired rowboats and rowed out into the harbor to hear her from there, faintly but distinctly.

The Castle Garden concert.Promoted shrewdly and outrageously by P. T. Barnum, the master of humbug, the Swedish coloratura became a sensation in America. Citizens who knew little or nothing about coloratura sopranos suddenly felt an intense need to hear the Swedish Nightingale warble her magical notes. Thousands thronged the piers to witness her arrival on September 1, some of them suffering bruises and bloody noses in the process; a fatal crush was narrowly avoided. To get her through the crowd, Barnum’s coachman had to clear the way with his whip. As for her first performance on September 11 at Castle Garden on the Battery, she astonished the packed audience with her vocal feats. All tickets having been sold already at auction, some without tickets hired rowboats and rowed out into the harbor to hear her from there, faintly but distinctly.3. The Hoopskirt, 1856

When news reached these shores that Eugénie, the Empress of the French, had adopted a new style of dress, the hoopskirt, averaging some three yards in width, the fashionable women of New York and the nation simply had to add this marvel of technology to their wardrobe, and the factories of New York bustled and hummed accordingly, turning out up to four thousand a day. For the next ten years or so, the ladies labored to maneuver through narrow doorways, and to sit gently and comfortably, in these cagelike monstrosities of fashion, until word came that the Empress of the French now favored quite another style, the bustle, which spelled the end of the hoopskirt.

An 1856 cutaway view from Punch.

An 1856 cutaway view from Punch.4. The Black Crook, 1866

It opened on September 12 at Niblo’s Garden, a huge theater on Broadway, and ran for a record 474 performances: a heady brew of a melodrama with a scheming villain who contracted to sell souls to the devil in exchange for magical powers. An extravaganza of extravaganzas with a hodgepodge of a plot, it featured a kidnapped heroine to be rescued by a hero; a fairy queen who appeared as a dove and was rescued from a serpent; a grotto with swans, nymphs, and sea gods that rose magically out of the floor; a devil appearing and disappearing in bursts of red light; fairies lolling on silver couches in a silver rain; angels dropping from the clouds in gilded chariots; a “baby ballet” with children; a fife and drum corps; the raucous explosion of a cancan with two hundred shapely legs kicking high, then exposing their frothy underthings and gauze-clad derrieres. When, at the end of the five-hour spectacle, the cast took their curtain calls before a wildly applauding audience, they were cheered by leering old men in the three front rows who pelted them with roses. Denounced from pulpits as “devilish heathen orgies” and “sins of Babylon,” it was a long-time smashing success, revived often on Broadway and touring the country for years. Some see it as the origin of both the Broadway musical and burlesque.

An 1866 poster. For spectacle, even the Met Opera today couldn't match it.

An 1866 poster. For spectacle, even the Met Opera today couldn't match it.5. Edison’s incandescent light, 1882

At 3:00 p.m. on September 4, 1882, Thomas Edison flicked a switch at his Pearl Street power plant in downtown Manhattan, suddenly illuminating the Stock Exchange, the offices of the nation’s largest newspapers, and certain private residences, including that of financial mogul J.P. Morgan. “I have accomplished all that I promised,” announced the Wizard of Menlo Park.

A young inventor already credited with the invention of the phonograph, Edison had demonstrated his new incandescent light bulb to potential backers in December 1879, and subsequently to the public. “When I am through,” he told the press, “only the rich will be able to afford candles.” Impressed, wealthy patrons such as Morgan and the Vanderbilts had invested in the enterprise. At his research laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, Edison and his team worked diligently to develop and patent the basic equipment needed, including six steam-powered dynamos, 27-ton “Jumbos,” the largest ever built. The dynamos at the Pearl Street plant were then connected by copper wires running underground to other buildings whose owners had contracted with Edison for illumination.

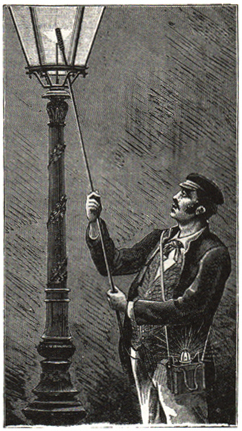

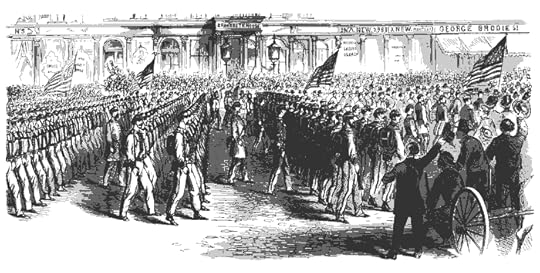

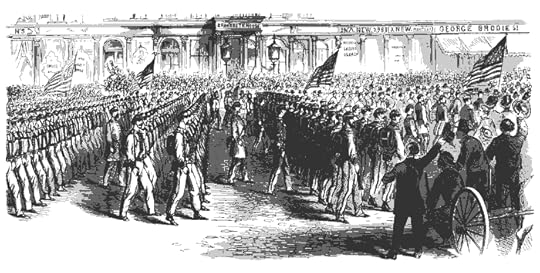

Laying Mr. Edison's electrical wires in the streets, 1882. The miracle of lighting by electricity had been demonstrated in New York, but throughout the nation the public held back, having heard reports of horses being shocked and workmen electrocuted. Insisting that electric light was clean, healthy, and efficient, not requiring the sprawling, foul-smelling facilities needed to provide gas for gas lighting, Edison staged an Electric Torch Light Parade where 4,000 men marched through Manhattan, their heads adorned with illuminated light bulbs connected to a horse-drawn, steam-powered generator. The marchers weren’t electrocuted, proving that electricity was safe, and the public was slowly won over. Hotels, restaurants, shops, and brothels soon became radiant with light. Darkness was banished and urban life transformed, and pickpockets could work in the evening.

Laying Mr. Edison's electrical wires in the streets, 1882. The miracle of lighting by electricity had been demonstrated in New York, but throughout the nation the public held back, having heard reports of horses being shocked and workmen electrocuted. Insisting that electric light was clean, healthy, and efficient, not requiring the sprawling, foul-smelling facilities needed to provide gas for gas lighting, Edison staged an Electric Torch Light Parade where 4,000 men marched through Manhattan, their heads adorned with illuminated light bulbs connected to a horse-drawn, steam-powered generator. The marchers weren’t electrocuted, proving that electricity was safe, and the public was slowly won over. Hotels, restaurants, shops, and brothels soon became radiant with light. Darkness was banished and urban life transformed, and pickpockets could work in the evening.6. First U.S. auto fatality, 1899

On September 13, 1899, Henry Hale Bliss, a real estate dealer, was struck by an electric-powered taxi while getting off a streetcar at West 74th Street and Central Park West, and knocked to the ground; rushed to a hospital, he died the following morning, the first such fatality in the nation. The taxi driver was arrested and charged with manslaughter, but was acquitted on the grounds of having exhibited no malice or negligence. All of which is a reminder that the Next Big Thing can bring perils as well as benefits. Installed on the centennial of the accident, a plaque commemorating his death now marks the spot.

7. The Armory Show, 1913

A 1913 button.The International Exhibition of Modern Art, held at the 69thRegiment Armory on Lexington Avenue between 25th and 26thStreets, introduced avant-garde European art to Americans who were primarily used to realism, shocking them with a heavy dose of Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. Especially jolting to their eyeballs was Marcel Duchamp’sNude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, which expressed motion through a succession of superimposed images not of human limbs, but of conical and cylindrical abstractions in brown, a double blast of Cubism and Futurism. Organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, this assemblage of 1300 works, including a fair number of nudes, was more than some could take. Accusations of quackery, insanity, immorality, and anarchy multiplied, parodies and cartoons mocked the show, and former president Theodore Roosevelt declared, “That’s not art!” But the civil authorities declined to close the exhibition down, and Americans began adjusting to the startling, radical, nerve-jolting, and precedent-shattering phenomenon that was modern art.

A 1913 button.The International Exhibition of Modern Art, held at the 69thRegiment Armory on Lexington Avenue between 25th and 26thStreets, introduced avant-garde European art to Americans who were primarily used to realism, shocking them with a heavy dose of Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. Especially jolting to their eyeballs was Marcel Duchamp’sNude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, which expressed motion through a succession of superimposed images not of human limbs, but of conical and cylindrical abstractions in brown, a double blast of Cubism and Futurism. Organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, this assemblage of 1300 works, including a fair number of nudes, was more than some could take. Accusations of quackery, insanity, immorality, and anarchy multiplied, parodies and cartoons mocked the show, and former president Theodore Roosevelt declared, “That’s not art!” But the civil authorities declined to close the exhibition down, and Americans began adjusting to the startling, radical, nerve-jolting, and precedent-shattering phenomenon that was modern art. Duchamp's descending nude.

Duchamp's descending nude.8. The Charleston, 1923

It burst upon the nation when a tune called “The Charleston” ended the first act of the Broadway show Runnin’ Wild, and the all-black cast did an exuberant, fast-stepping dance that grabbed the audience, the city, and the nation, and then went on, some say, to become the most popular dance of all time. (But what about the waltz?) The song’s African American composer, James P. Johnson, had first seen the then-unnamed dance danced in 1913 in a New York cellar dive frequented by blacks from Charleston, South Carolina, who danced and screamed all night; inspired, Johnson then composed several numbers for the dance, including the one made popular by the musical. But the dance itself, which made the tango seem tame and the waltz antiquated, has been traced back to the Ashanti tribe of the African Gold Coast. The dance was brought to this country by slaves; after emancipation, African Americans seeking jobs in the North brought it to Chicago and New York, where Johnson discovered it, and the rest is history.

The dance spread like fever. Dance halls and hotels featured Charleston contests; ads in New York papers seeking a black cook, maid, waiter, or gardener insisted, “Must be able to do the Charleston,” so they could teach their employers the dance; hospitals throughout the country began admitting patients complaining of “Charleston knee”; an evangelist in Oregon called it “the first step toward hell”; and the collapse of three floors above a dance club in Boston, killing fifty patrons, was blamed on vibrations of Charleston dancers, causing the mayor to ban the dance from all public dance halls. But the more the dance was censured or banned, the more popular it became; the whole nation was “Charleston mad.” (Ragtime, then jazz, then the Charleston: the African American contribution to American pop culture has been phenomenal.)

A personal aside: I discovered the Charleston when I sawThe Boyfriend, a frothy 1954 Broadway musical that re-created and spoofed the musicals of the 1920s, while vaulting Julie Andrews into stardom. Ever since, having been raised on the waltz and the foxtrot, I’ve wanted to do the Charleston, but never found anyone to teach it to me. I’d like to say that my parents did the dance, but they were in their thirties when it burst upon the scene, and living quietly in and near Chicago, untroubled by Al Capone and his cohorts, and raising one infant son and soon expecting another (guess who). In my later years, feeling totally uninhibited at last, I did my share of wild dancing, but never the Charleston, for which I feel grievously deprived. Why the Charleston? It’s joyous, it’s crazy, it’s wild. Go check it out on You Tube and you’ll see what I mean. But I don’t plan to do it now. If I did, the Daily Drivel, a tabloid published only in my mind, would flash a headline:

OCTOGENARIAN RISKSFRACTURING HIS HIPWHILE DOING THECHARLESTON

DOCTORS ADVISETRANQUILIZERSAND THERAPY

(P.S. to the above. Thanks to two charming young teachers on You Tube, I have in fact learned a basic step or two of the Charleston, which I now do wildly in my apartment, humming to myself some jazzy music probably snatched from The Boyfriend. So far, no mishap. I urge everyone in the mood for a bit of craziness to learn, at least a little bit, this wild and crazy dance. It banishes tedium, relieves depression, and incites joy.)

9. New York World’s Fair, 1939-1940

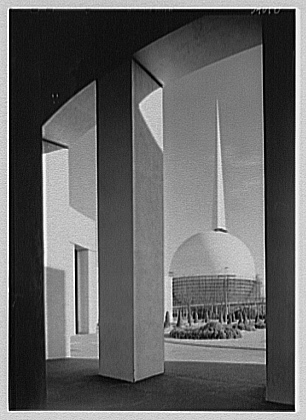

A view of the Trylon and Perisphere.Covering 1200 acres in Flushing Meadows Park in Queens, it exposed 44 million visitors to “the World of Tomorrow,” as embodied in the Trylon, a soaring 610-foot spire, and the Perisphere, a huge sphere housing a diorama depicting a utopian city of the future. The fair’s modernistic vision of the future was meant to lift the spirits of the country, which was just barely emerging from the Great Depression, and meant also, of course, to bring business to New York. (Little did the optimistic planners realize that the world was about to be convulsed by World War II.) Exhibits included the Westinghouse Time Capsule, a tube buried on the fair’s site and containing writings by Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann, copies of Life Magazine, a Mickey Mouse watch, a kewpie doll, a pack of Camel cigarettes, and other goodies meant to convey the essence of twentieth-century American culture. A Book of Record deposited with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington contains instructions for locating the buried capsule, instructions that will be translated into future languages with the passage of time. One indeed wonders what future generations, if such there be, will think of us when, if all goes as planned, they locate and open the buried capsule a mere 5,000 years from now.

A view of the Trylon and Perisphere.Covering 1200 acres in Flushing Meadows Park in Queens, it exposed 44 million visitors to “the World of Tomorrow,” as embodied in the Trylon, a soaring 610-foot spire, and the Perisphere, a huge sphere housing a diorama depicting a utopian city of the future. The fair’s modernistic vision of the future was meant to lift the spirits of the country, which was just barely emerging from the Great Depression, and meant also, of course, to bring business to New York. (Little did the optimistic planners realize that the world was about to be convulsed by World War II.) Exhibits included the Westinghouse Time Capsule, a tube buried on the fair’s site and containing writings by Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann, copies of Life Magazine, a Mickey Mouse watch, a kewpie doll, a pack of Camel cigarettes, and other goodies meant to convey the essence of twentieth-century American culture. A Book of Record deposited with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington contains instructions for locating the buried capsule, instructions that will be translated into future languages with the passage of time. One indeed wonders what future generations, if such there be, will think of us when, if all goes as planned, they locate and open the buried capsule a mere 5,000 years from now. The Futurama exhibit, showing a street intersection

The Futurama exhibit, showing a street intersection of the City of Tomorrow. I'll let residents of New York

and our other big cities report to what extent this