Sue Burke's Blog, page 81

June 6, 2012

Haiku cut: kireji

Haiku is plagued by rules, some of which are false. Others are little-known but essential.

False: the idea that a haiku consists of 3-5-3 lines. I'll let Gabi Greve and Haiku Society discuss that. In Japanese, there is a count, but it's not exactly English syllables.

Fewer people know about the kireji, or "cutting word." In Japanese, these act sort of like punctuation or add grammatical structure, and function similarly to the volta or turn in a classic sonnet. The kireji cuts the poem into two parts. In Japanese, a kireji may indicate a question, emphasis, surprise, completion, probability, cause, or interrelationship.

In English, these words are sometimes represented by punctuation, such as colons, dashes, commas, ellipsis, exclamation points, or question marks (: — , … ! ?) or words like but, how, and, yet, now, this, still (and a lot more) or simply by a line break.

Kireji link two ideas. The best haiku have more depth than a simple observation; they link an observation, often about the changes in nature and its seasons, to something else.

Kireji also free the poet from the constraints of a sentence. Words can be left out, and fragments of sentences can be connected to create both emphasis and brevity. (If you love 17-syllable sentences, you may wish to investigate the poetic form of American sentences.)

How does this work? Here are some of my haiku, offered humbly to avoid plagiarizing other better poets:

hard to say:

which day did the robins

leave town?

Christmas eve —

the woman in the checkout line

blinking back tears

back to school —

even the playground trees

are taller

old man

thinks no one is watching

and limps

(Here and is the kireji.)

bus stop

an empty bench

and a bag lunch

(It's and again.)

songbird hatchling

dead on the sidewalk

but Spring does not pause

(but)

finally

on last year's poinsettia

a red leaf

(line breaks)

open gate

a girl climbs the playground fence

anyway

(Here the kireji is anyway. The location at the end of the haiku brings you back to the beginning, and gives an emotional closure to the poem.)

These haiku also include the traditional immediacy and personal experience — I saw all those things and was inspired by them. Something happened in the context of something else that created a meaning beyond the words themselves.

………

Recommended resources for learning more about Haiku:

World Haiku Review archives

http://whrarchives.wordpress.com/

Happy Haiku Archives

http://happyhaiku.blogspot.com.es/2000_07_01_happyhaiku_archive.html

— Sue Burke

Also posted at my professional writer's website:

May 30, 2012

20th anniversary

Jerry Finn and I were married 20 years ago today in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

The Burke family.

The Finn family.

May 23, 2012

For terrified tourists: Knives to the natural one

As a public service, here's the menu in its original Spanish, the bad translation, and what you really get:

Berberechos al natural

Cockles to the natural one

Cockles in their own juice, au naturale

Navajas al natural

Knives to the natural one

Razor clams in their own juice, au naturale

Mejillones en escabeche

Mussels pick leed

Pickled mussels, in spiced vinegar dressing

Almejas al natural

Clams to the natural one

Clams in their own juice, au naturale

Boquerones en vinagre

In vinegar anchovys

Anchovies in vinegar

Sardinillas en aciete

Sardines in oil

Small sardines in oil

Aceitunas rellenas

Olives stuffing

Stuffed olives

Almendras saladas

Saliferous almonds

Salted almonds

Bon appetit.

— Sue Burke

May 16, 2012

Go Ahead — Rewrite This Story

Rewriting isn't evil, although it can feel that way. No one gets it right the first time.

When you revise, watch out for: Starting in the wrong place. Ending in the wrong place. Scenes that should be moved around. Unnecessary characters or scenes. Missing scenes. Missing motives. Adverbs, adjectives, and weak verbs. Weak conflicts. Slow pacing. Few sensory details. Inconsistent or wrong point of view. Wooden dialogue. Wooden characters. Clichés. Unvarying sentences. The wrong title. No final meaning.

In other words, everything is up for grabs, and repeated rewriting will make you an evil genius. If you need an idea, here's a few:

• This is a story about a space cruiser company president who goes to court to fight charges that his "employee services" program providing for their personal needs has devolved into virtual slavery.

• This is a rather literary alternate history novelette set in 1493 shortly after it becomes clear to the royal court of Spain that Admiral Christopher Columbus and his ships will never return.

• This is a humorous horror story about a house sold with the advice that its ghost is placated by attractive artwork, but the new owner's taste turns out to be awful.

— Sue Burke

May 13, 2012

Spanish Revolution: May 12

The movement goes by many names, especially 15M, because it began on May 15, 2011. A protest in Madrid last year turned into a camp, an occupation in the city's central plaza, Sol. The protesters are sometimes called the Indignados, indignant at the way the market economy is going. "We're not against the system, the system is against us," is one of their slogans.

The camp was broken up in summer and some thought — or hoped — the movement had waned. But on the one-year anniversary, the streets and plazas of Madrid were full of life again.

The protest converged on Sol from four directions. The South March came with music.

It filled Atocha Street.

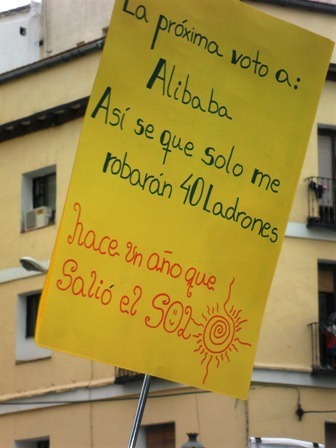

This sign says: "The next time I'm voting for Ali Baba. That way only 40 thieves will rob me. It's been a year since the SUN same out." (Sol = Sun)

At Sol. The protest is reflected in the entrance to the subway.

A report and video at CNN:

http://edition.cnn.com/2012/05/12/world/europe/spain-protests/index.html?hpt=hp_t2

— Sue Burke

May 11, 2012

Amadis of Gaul and Zombies!

I couldn't help myself. There aren't enough stories about zombies in medieval literature, so I wrote one.

As you know, I've been translating the Spanish medieval novel Amadis of Gaul a chapter at a time online for a while. Now there's chapter XXVIII½.

You can read it here:

http://amadisofgaul.blogspot.com.es/2012/05/chapter-xxviii-amadis-of-gaul-and.html

— Sue Burke

May 3, 2012

More grammar: You can't count cash

How much cash do you have right now? Five cashes, twenty-two cashes?

No, you might have a lot of cash, twenty-two dollars....

That's because you can't count cash. It's a grammatical thing. English nouns come in two categories: countable and uncountable.

Countable nouns are usually the names of objects, concepts, people, and things that can be enumerated: books, potatoes, teachers, etc.

Uncountable nouns are usually liquids, materials, abstractions, languages, collections, and other things that do not occur separately: milk, information, sugar, advice, copper, weather, flu, etc.

(A few things, like stone, time, space, wine, and room, can be both countable and uncountable, and often their meaning changes depending on their use: We are out of room. We have seven rooms in our house.)

With uncountable nouns, you can use words like a little, a lot of, much, some, hardy any, no or classifiers like a pound of, a bottle of. For example: I have a bottle of wine. I have a little crackers and cheese. I have a lot of trouble planning parties. But you can't say: I have many cash. I have learned a few French.

With countable nouns, you can use words including a lot of, many, a few, some, and any. You can also make the nouns plural: You had a few dollars. Can you buy some apples? You will find many chairs and a few tables in the workroom. But you can't say: You have much teachers. You own little bluejeans.

If you're a native speaker, of course, you know all this automatically. That's because we don't think about grammar when we speak, we remember the groups of words that express our intent. An alert person who grows up surrounded by educated speakers could use perfect grammar without ever studying it.

But if you're learning English, countable and uncountable nouns will be yet another annoying detail to memorize and a source of frequent error.

Is English a difficult language to learn? Yes and no. It starts easy, with fairly direct grammar, and even if you say, "She want to eat many cheese for lunch," people are likely to understand you. But then English gets complex, with various classes of nouns, an excessive number of prepositions, confusing phrasal verbs, tricky participle phrases, and an infinite vocabulary.

So, after all these years, I still study grammar, if only to understand why I use the words I do.

— Sue Burke

Also posted at my writing website:

April 26, 2012

Couplets: poetry on tour

April is National Poetry Month. To celebrate, Upper Rubber Boot Books is coordinating a book blog tour called Couplets, and today I'm proud to host Sr. Anne M. Higgins.

Fifty poets are participating in this tour. You can find links to other Couplets posts at:

http://www.upperrubberboot.com/couplets-a-multi-author-poetry-blog-tour/

………

Couplets: My life as a poet

by Sr. Anne M. Higgins

I wrote my first poem in fourth grade, at the encouragement of my teacher. It was nine-year-old occasional verse about Thanksgiving Day … but I had an ear for rhythm and rhyme. And I liked writing poetry, figuring out how to put words together.

My poems began to move into open form in high school, though I was still telling more than showing; still philosophizing. But they were published in the high school literary magazine, which was called Flight — prophetic for me as a future birder! Sometime in high school I found the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins … loved his poem "Heaven Haven" and really loved figuring out the meaning of his poem "Spring and Fall: to a Young Child." I loved the way he played with words, and the sprung rhythm he used, and I began to imitate his style.

In college, I had some good mentoring from Martin Galvin, a poet and professor at my school. It was then that I began to write as a practice, rather than writing as a way of explaining the world to myself.

My first poem published in a magazine was published by Commonweal in September of 1970; I literally collapsed on the floor when I read the acceptance letter! It was called "The Engineer on the Train" and described my encounter with a businessman/mathematician on a train trip from Baltimore to New York.

During the first five years after college, my poetry writing went into a major slump for many reasons. Finally I began to settle down; I was going to grad school at Hopkins in the evenings and summers while teaching at Seton, a Catholic girls' high school. In the midst of that organized busy-ness, I began to write again. Commonweal published a second poem: "Elizabeth Seton" about the newly canonized saint the school was named for:

Elizabeth Seton

Proud straight woman

with the snapping eyes,

you had to look up

to your benefactors.

You had to sail oceans

to make up your mind,

and lose all your lace

to be stubborn.

You had to be cold

in a damp stone house,

rubbing your hands together

before you could play

that piano,

and you had to wear black

enough

to understand.

Proud loving woman,

pulled into heaven

between last minute

reminders

to earth!

This, too, was a prophetic poem. In 1978, at the age of 30, I joined the Daughters of Charity, the order of Sisters with whom I was teaching. Needless to say, it was a major life change!

My belonging to this new life has never prevented me from writing poetry, though, and in the last twelve years I have also been going to poetry conferences, meeting other poets, and widening my own writing. Since 1970, I've had about 100 poems published in small magazines, both print and online. I was especially excited when Garrison Keillor read two of my poems on The Writer's Almanac — one in October 2001, and the other in August 2010.

I write both fixed form and open form poems, though the open form ones predominate.

Josephine Jacobsen, a marvelous poet who died in 2002 at the age of 94, was my mentor for thirty years, and she used to say that it was the poem itself which dictated the form. I agree.

Here is an open form poem which grew out of a Boccaccio story and two paintings:

Handling the Pot of Basil

Holman Hunt, on his honeymoon,

used his wife as the model for Isabella.

She's passionately warm and fleshed out,

large dark eyes wide, head resting on

the pot of basil. Half of her

waist length black hair

is draped over the top of the pot.

The basil plant flourishes,

passionate and fleshy, bushy

and glistening.

The pot itself is full bellied,

gilt porcelain, richly designed,

though skulls the size of tennis balls

adorn four sides of its base.

Isabel had a lover, Lorenzo.

Her brothers lured him away

and murdered him

for the sake of the family honor,

buried his body and told her

Lorenzo had gone to another town.

But in a dream she sought him;

his ghost led her to his grave.

She dug up his body,

sliced off the head,

wrapped it in a shawl,

took it home,

planted it in that ornate pot,

planted the basil on his crown,

and covered it all with soil.

She watered this plant with her tears,

which it must have liked.

So, between the softly decaying

sinuses and corneas,

the tongue, though more earthy now,

whispered love words to her,

while the teeth grinned through the roots.

John White Alexander painted her, too,

in 1897.

Here, she's wan as the pot,

in which no basil is evident.

Trance-trapped, she's lit from below.

Her fingers trace shadows on the skin of the pot.

Her feet are hidden beneath volumes

of gauzy white nightgown.

*

Eventually those damned

interfering brothers,

seeing that she had gone round the bend,

crazed with grief,

wondered why she lingered with the basil plant

on which she lavished care and tears.

They took it from her,

upended it, and finding

the remnants of tissue,

tearstained skull,

knew they must get out of town,

far away.

The story does not tell

what happened to Isabella.

That's something else I love to do: write ekphrastic poems. I love to wander the Phillips Gallery in Washington in some kind of daze, waiting for a painting to call out to me.

For the last twelve years, I've had the joy of teaching English at Mt. St. Mary's University, a small coed school set on the side of a mountain in rural Maryland. I teach Freshman Comp as well as a variety of other courses — my favorite is Introduction to Poetry, where I get to introduce my students — mostly non-English majors, and all four years of undergrad school — to the work of poets I love: Richard Wilbur, Emily Dickinson, Dylan Thomas, Theodore Roethke, Elizabeth Bishop, and yes, Gerard Manley Hopkins.

During these years, after countless rejections, I have finally had some five books of poetry published. This didn't happen until I was in my fifties, so I say to younger poets — don't lose heart!

April 19, 2012

A medieval Spanish dinner you can make at home

http://jaletaclegg.blogspot.com.es/2012/04/thursday-recipe-medieval-feast.html

The recipes are easy and tasty — almost timeless.

— Sue Burke

April 18, 2012

Go Ahead — Write This Story: Borrowing ideas

Is fan fiction evil? It's not new, that's for sure, and some highly regarded work has been based on earlier literature, borrowing from Shakespeare, the Bible, the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Charlotte Brontë, Beowulf, and Gulliver's Travels. Why? Borrowing characters or situations allows you to enter into the imaginative world of another writer, to understand that particular world, and to build from it. So don't be ashamed, whether you're inspired by Milton's Paradise Lost or Lost in Space. If you prefer to write an original story, here's a few ideas.

• This is a sword and sorcery story about a Viking who believes he has met Odin — or at least a being with great talents in magic and death.

• This is a first contact humorous novella (with recipes) about a silicon-eater who has come to Earth in search of gourmet opals.

• This is an urban ecological horror story in which vampires deal with the problem that their ability to navigate while in bat form is compromised by the electromagnetic fields from cellular telephones.

— Sue Burke