Sue Burke's Blog, page 73

September 4, 2013

Machines can translate ... some things

The original:

“Las guerras daban excusa a los peruleros para medros y rápidas ganancias, aunque, también, para perder la cabeza de sobre los hombros o andarse huido en las selvas entre las alimañas si no se acertaba el ganador en esa suerte de como lotería.”

Babylon (http://traductor.babylon.com/):

“Wars gave an excuse for the peruleros for limitless ambition and rapid gains, though, also, to lose the head of on the shoulders or prevaricate fled in the jungles between the vermin was difficult if not the winner in that sort of as lottery.”

Google Translate (http://translate.google.com/):

“The war gave the Peruvians excuse for Medros and quick profits, but also to lose his head over the shoulders or beating fled in the forests between the vermin if not the winner was right in that sort of like lottery.”

Instituto Cervantes (http://traductor.cervantes.es/):

“The wars gave excuse to the peruleros for medros and fast gains, although, also, to lose the head of on the shoulders or walk escaped in the jungles between the alimañas if it did not hit the winner in this luck of as lottery.”

My translation:

“For the conquistadors in Peru, these wars provided a pretext for advancement and quick profit, though they might also result in sudden death or flight, wandering through the jungle amid its predators, for failing to guess the winning side in that lottery of fate.”

………

This article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, “Machine Translation Without the Translation,” explains how Google Translate works and why it makes mistakes.

http://chronicle.com/blogs/linguafranca/2013/05/31/machine-translation/

………

If you’re looking for a translator, here’s my LinkedIn profile:

http://www.linkedin.com/in/sueburke

August 28, 2013

Another impossible moment

At one time, my alarm clock and my telephone (a fixed line — this was a long time ago) sat next to each other on the headboard of my bed.

One night I was awoken out of a deep sleep by the alarm clock (or so I thought). To switch it off (I was very groggy), I picked up the telephone handset. My alarm clock began telling me that it had left its sunglasses and softball with me. It wanted them back.

I know I said something in response, and in fact my alarm clock and I had a short conversation, but I don’t remember anything I said. I was too busy trying to figure out how an alarm clock could play softball. As an electric clock, it didn’t even have hands. It also didn’t have eyes, so why would it need sunglasses?

Could there be clock softball leagues? And who knew my alarm clock had a female voice?

The other party ended the conversation, and as I began to hang up the handset, I slowly understood what had happened. I had recently had a party. Someone had forgotten her sunglasses and a softball. My guest had called to recover them.

I had not talked to the alarm clock.

I asked around, and I waited for her to call back, but she never did. (What had I said?) After a year, I began to wear the sunglasses (hoping someone would recognize them), and eventually I gave the softball to the neighbor boys.

Inanimate objects rarely converse with us. One of my treasured memories, besides the time when the sun set in the east, is the time when I really thought I was talking to an alarm clock.

— Sue Burke

August 21, 2013

Go Ahead — Write This Story: Classic tragedy

Tragedy began as a drama form in Ancient Greece, a story about a good person who makes an error or has a flaw that causes unforeseen ruinous or sorrowful results. The tragic hero should be good, even great and admirable, so his or her downfall will evoke sympathy in the spectators or readers. The cause of the downfall should come from within the character, or the story is a misfortune but not a tragedy: the hero should do something ignorant, mistaken, deliberate, or accidental, or fail to act. Tragedy has withstood a long test of time with many variations, and modern horror stories sometimes follow its pattern.

If you’d like to write a tragedy, here are a few ideas:

• This is a story about a woman who recovers an object she had hidden in a past life, but she can't remember why she had hidden it.

• This is a military SF story about a noble warrior from another planet who arrives during Earth's Cold War and is confused by the Berlin Wall.

• This is high fantasy quest set in several successive centuries about a wizard who attempts to rescue the last unicorn, told from the point of view of the unicorn.

— Sue Burke

August 15, 2013

Why I couldn’t buy postage stamps

I’m looking for work as a translator, so I’m sending out resumes, and yesterday morning I needed postage stamps. Here in Spain, you can buy stamps at estancos, government-licensed stores that sell tobacco and (for historical reasons) stamps.

There’s an estanco around the corner from my house, so I headed there. According to a sign on the door, it was closed until Sunday for vacation. That was no big surprise. August is vacation month in Spain (and Europe), and a lot of businesses are closed.

I also wanted to buy a newspaper, but the newspaper stand across the street from the estanco has been closed all month. The next-nearest newspaper stand is closed until August 19, so I had already planned to go to the one a few blocks farther away.

I knew of another estanco on Cavanilles Street, which was a few blocks out of my way to the newspaper stand, but I thought I’d try. It was closed.

Then I checked the estanco next to the newspaper stand where I was headed, which I was pretty sure was closed for August vacation and which was why I didn’t go there first, and I was right, it was closed.

I asked the señora at the newspaper stand where I could find an open estanco. She directed me to the one on Barcelona Avenue next to the basilica. That was only a few more blocks out of my way on the trip home, so I went there. It was open, but it was out of stamps. The señora there suggested going to the post office.

Of course, I can’t do that today because it’s a public holiday, the Assumption of the Virgin, and the post office is closed.

Have a happy August. It’s very quiet here because no one is doing anything.

— Sue Burke

August 14, 2013

An impossible moment

So one evening I was sitting with a friend at a seaside restaurant in Los Angeles, and I saw that the sun was setting over water. That meant it was setting in the east!

Had the Earth reversed its orbit? I looked around in a sudden panic. Other people chatted happily, enjoying their dinner. Was I the only one who had noticed?

And if the Earth had reversed its orbit or the sun had gone rogue or whatever, that would have had serious consequences: giant earthquakes, maybe. Yet even though we were in Los Angeles, the ground remained steady.

Oh, right, Los Angeles. Pacific Ocean. In the west. It’s okay.

But for a terrifying and astounding instant, the cosmos had gone completely wrong. That impossible moment, that enormous feeling, has always been one of my treasures.

— Sue Burke

August 7, 2013

The novel that changed Spanish science fiction

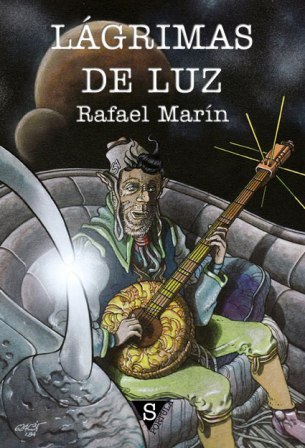

Lágrimas de luz [Tears of Light] by Rafael Marín is often called the “before and after” novel in Spanish science fiction. Published in 1984, and written a few years earlier when Marín was only 22 years old, it proved that a Spanish author could write an ambitious literary work of science fiction.

This might sound odd. Of course Spanish authors could – but they had to believe that themselves, and they had reason to doubt it. For the previous two centuries, realism and naturalism had reigned supreme in Spanish literature. Despite “futurist” authors like Nilo María Fabra, Spanish science fiction (and fantasy and horror) didn’t exist and wasn’t possible.

In the English-speaking world, science fiction set down its roots in the early 20th century, first as pulp and then as more serious works. Spain had its pulp too, starting from the 1950s, although its authors usually wrote under Anglo-Saxon pseudonyms like Louis G. Milk or George H. White at the behest of publishers, who did not think openly Spanish authors, pulp or serious, would sell. Top English-language authors like Alfred Bester and Roger Zelazny were available in translation, though, and they made their mark.

From 1968 to 1982, a fanzine with a professional attitude, Nueva Dimension, edited by Domingo Santos, provided budding authors with a chance to grow, and some solid works began to appear. But nothing caught readers’ attention like Lágrimas de luz.

The novel’s plot

During the Third Middle Ages, a young man named Hamlet Evans, living in a small town that manufactures food, aspires to more in life than toiling in a factory, numbed by drugs and sex. He wants to be a poet, specifically one of the bards whose songs celebrate the Corporation that expands the human empire and protects it from its enemies. He is accepted, trains at the bards’ monastery, and is assigned his first military ship.

Soon he learns that the glorious triumphs of the empire are anything but: indigenous life forms are cruelly wiped out and the planets’ resources are stripped as the Corporation expands its iron grasp. Disillusioned, Hamlet can no longer compose acceptable epic poems. He resigns and is set down on the first available planet, which turns out to be under punishment for a rebellion against the Corporation. He barely survives, eventually escaping to join a small theater group and then a circus. The Corporation, meanwhile, decides that no entertainment that fails to extol its greatness can continue to exist, and sends troops to wipe them out.

Hamlet escapes again, and he decides to continue an outlaw artistic existence to defy the Corporation.

Ambitious and Spanish

Marín himself has called the novel an “ambitious space opera,” which it is, offering careful characterization and thematic development. Hamlet matures as a man and an artist in a fully-imagined universe. Like most first novels, it’s not perfect, especially some of the wooden and long-winded dialogue, but the action scenes are riveting and the prose is polished, at times even soaring.

As critic Mariela González pointed out in her analysis, Lágrimas de Luz: Postmodernidad y estilo en la ciencia ficción española, the novel makes a clean break from pulp. It features protagonist who is hardly a hero, and its themes include the search for beauty, and the crisis and alienation of youth. Rather than save the universe, Hamlet can barely save himself, and the universe might not even merit saving: no lightweight escapism here.

The story also draws on Spain’s own medieval past and brings it into the future. The bards’ songs echo works like El Cid that had once been popularly sung throughout the land – a past oral culture updated for the novel’s present. The novel also responds in its own way to Robert Heinlein’s Space Troopers and openly draws on themes from Moby Dick and other classics.

The next steps

The surprise of Lágrimas de luz didn’t usher in a sudden boom in Spanish science fiction. That waited until the 1990s with works by authors like Juan Miguel Aguilera, Elia Barceló, Javier Negrete, and Rodolfo Martínez, among many others, but the door had been opened. The genre continues to struggle, especially in the current economic crisis, and I have witnessed that too many Spanish science fiction fans do not yet believe that Spanish authors can write as well as English-language authors. (I try to convince them otherwise.) The road still heads uphill, but the problems are economic now, not artistic.

Rafael Marín, by the way, has continued to write and now has a long list of outstanding works to his name. Lágrimas de Luz is still in print after all these years and is available at Sportula, Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble, Casa del Libro, Ender, and Smashwords.

— Sue Burke

Also posted at my professional website,

July 25, 2013

A decade of Ignotus-winning novels

The Ignotus Awards are presented by the Spanish Association of Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Horror at the annual national convention, Hispacon. In many ways, they resemble the Hugo Awards presented at Worldcon; the Ignotus recogizes works in many categories, including novels, short stories, magazines, poems, artwork, and websites.

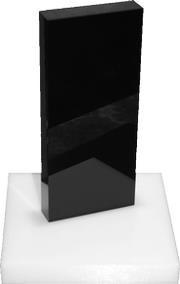

The Ignotus Award is a black marble monolith. It shares the Hugo’s strengths and weaknesses: relatively few people vote (starting this year, the voting base has been dramatically expanded), but those voters are intensely engaged, so while the choice of winners might generate controversy, no one can argue that they don’t rank among the year’s best.

2012: Fieramente humano [Fiercely Human] by Rodolfo Martínez. This complex urban fantasy returns to a city that has appeared in other novels, and it is a character in itself. An assassin arrives in the city to settle a thirty-year-old debt with Doctor Zanzaborna, a sorcerer, and police officer Gabriel Márquez learns that he was involved in supernatural events in his past without his knowledge.

2011: Crónicas del Multiverso [Chronicles of the Multiverse] by Victor Conde. Part of the Multiverse saga. The Variety is a small universe surrounded by a cosmic void and filled with a different life forms and civilizations. A space pirate steals an object from the Urtianos that is so valuable that they will go to war against all other intelligent species to recover it. The Urtianos also know that their universe is about to die.

2010: Última noche de Hipatia [The Last Night of Hypatia] by Eduardo Vaquerizo. A tragic love story framed by the city of Alexandria. A new disciple arrives from a far-off land, and Hypatia suspects he has a secret. In fact, he is from the future and knows that she will soon face a losing battle with fanaticism.

2009: Día de Perros [Dog Day] by David Jasso. Two teenagers spot a stray dog and decide to take it to its master and ask for a reward. In this novel about friendship and psychological suffering, their simple plan soon spirals down into suspense and horror.

2008: Alejandro Magno y las Águilas de Roma [Alexander the Great and the Eagles of Rome] by Javier Negrete. Alexander, the best military strategist in history, survives an attempted poisoning and decides to turn west and conquer Europe. To do that, he must defeat the incipient Roman Empire. Multiple points of view enrich this alternate history.

2007: Juglar [Jongleur] by Rafael Marín. In medieval Spain, the orphan Esteban survives in the rough world of the Spanish Reconquest by his wits, poetry, knavery, and magic. Torn between good and evil, he uses his skills to fill the post of troubadour for Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, “El Cid.” When El Cid dies, Esteban’s black arts might help win a crucial battle.

2006: Danza de tinieblas [Dance in the Shadows] by Eduardo Vaquerizo. In this alternate history, the Spanish empire forged in the 16th and 17th centuries lasts until 1927, the year in which the book takes place. Schemers, dissolute nobles, and inquisitive monks populate Madrid, while a series of murders in Salamanca threaten to reveal a mystery that could bring down the empire. There is nothing Victorian about the novel’s steampunk setting.

2005: El sueño del rey rojo [The Red King’s Dream] by Rodolfo Martínez. Andrea finds a computer disk next to a dead man that contains the code to create an artificial intelligence. Alex recognizes the code as the one used to recreate his associate Lurquer as an artificial intelligence shortly before his suicide. Amid their personal rivalries, they discover that the dead man does not seem to have existed, but a worldwide conspiracy does.

2004: La espada de fuego [The Sword of Fire] by Javier Negrete. This epic fantasy, part of a trilogy, centers on Zemal, a legendary sword of fire and symbol of power that every warrior aspires to possess. Seven aspirants fight for it in a battle that eventually threatens to break the peace between gods and men. Warriors and sorcerers must unite to defeat chaos and destruction.

2003: Cinco días antes [Five Days Earlier] by Carlos F. Castrosín. In the near future, a police officer recovering from injuries in a bomb blast is assigned to investigate the murder of an alderman in Supra Beni, a megalopolis suffering from rampant corruption. Supra Beni is a single giant building that developed from today’s Benidorm, a tourist city filled with skyscrapers on the Mediterranean coast near Valencia.

— Sue Burke

Also posted at the AEFCFT website, http://www.aefcft.com/a-decade-of-ignotus-winning-novels/

July 24, 2013

Ignotus nomination!

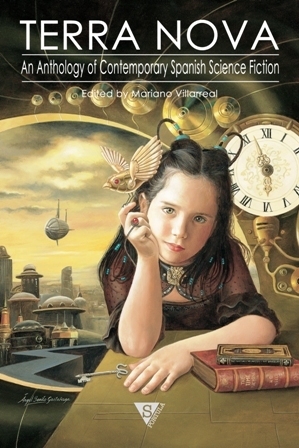

A story I translated into English for Terra Nova: An Anthology of Contemporary Spanish Science Fiction, has been nominated for an Ignotus Award in its original Spanish-language version. This is the equivalent of a Hugo in Spain.

The story is “La textura de las palabras” [“The Texture of Words”] by Felicidad Martínez. It tells of a woman’s fight for leadership on a planet where women are blind and dependent, and men fight constant wars.

Terra Nova: Antología de ciencia ficción contemporánea has also received seven other Ignotus nominations: best anthology, best novella, best short story (two nominations), best cover art, and best foreign short story (two nominations).

Winners will be announced at HispaCon, the Spanish national science fiction convention, in fall.

— Sue Burke

P.S. Buy your English-language copy now.

Smashwords, in a variety of electronic formats:

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/328358

Amazon, in Kindle format:

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00DJVMBHC

Amazon, in paperback:

http://www.amazon.com/dp/8494127489/

Sportula, the Spanish publisher:

http://www.sportularium.com/?p=2336

July 17, 2013

Go Ahead — Write This Story: Open without credits

You can learn a lot about storytelling from the movies — but some of those lessons do not apply to written works. In particular, movies have traditionally started slowly, sometimes showing scenery or general background activities, like the heroine driving a car. But what’s really happening is the showing of the opening credits, and movie-makers don’t want footage that will compete with the names of the actors and director for the viewer’s attention. In written fiction, you want to engage the reader’s attention from the first paragraph, if possible from the first sentence, maybe even from the first word.

If you need a fast-starting story idea, here are a few:

• This is a hard SF short story about the possibility that stone artifacts from a lost civilization have sentience.

• This is a traditional horror story in which the spirits of those who were dissatisfied with their final hours as mortals try to unite to find peace.

• This is a sibling rivalry story about a photojournalist documenting the Second Dustbowl who is accepted into a tribe of Wyoming Bedouin.

— Sue Burke

July 10, 2013

What you should know about science fiction from Spain

An article about science fiction from Spain, which also appears (in a longer version) in Terra Nova: An Anthology of Contemporary Science Fiction, has been published in Europa SF. The article was written by Mariano Villareal, the anthology’s editor, and translated to English by me:

http://scifiportal.eu/science-fiction-from-spain-mariano-villareal-spain/

To buy the anthology, which came out last month:

Smashwords, in a variety of electronic formats:

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/328358

Amazon, in Kindle format:

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00DJVMBHC

Amazon, in paperback:

http://www.amazon.com/dp/8494127489/

Sportula, the Spanish publisher:

http://www.sportularium.com/?p=2336

— Sue Burke