Sue Burke's Blog, page 6

October 9, 2024

Intricate Stardust

(I wrote this at a workshop for imagining science last spring at the Chicago Botanic Garden. It came as the result of a writing prompt, and I thought about something I’d seen that morning in one of the gardens.)

***

The rabbit was twitching and bleeding. The edge of the universe was far away — in scientific terms, fully 1027 centimeters. Less than one centimeter away were the talons of a hawk, and soon, the rabbit would be still.

You watched this drama unfold on that spring morning, knowing that you lived on a planet tilted in its orbit toward the sun, which created the seasons. Above, unseen in daytime skies, countless stars swirled within galaxies and super-clusters of galaxies. The thought made you shiver. What did this vast universe want?

The rabbit knew. It wanted to live, but as you understood, only sentient things felt real wants, and the universe, with its great distances, existed impersonally.

So you moved on, sure that the universe had no hidden intent, but you had too much at stake in the cosmos to stop wondering.

Long ago, when the universe was young, it had been populated by huge blue stars that burned hot, collapsed, and exploded. New stars gathered from their dust, burned, collapsed, and exploded, each time creating more complex matter. Some of the stardust had accumulated into a planet — your home — orbiting a stable star, so in this particular place, the universe had grown exceptionally complex. Stardust had reached sentience.

You were sentient and full of doubt on that sunny spring morning, near a bleeding rabbit, and like the rabbit, you wanted to live. Then, you found your real question: Why was life so brief? But what did brevity mean in an expanding universe? Across vast time and deep space, the universe continued to form and re-form with wants and doubts generated by intricate stardust. When you looked at the rabbit, you saw yourself.

The rabbit must have had doubts, too, however brief and small. Did stars ever doubt in one sense or another? Because at this time and this space, the universe was twitching and self-aware, and through you, it would continue to move on.

October 7, 2024

A chat at SciFiScavenger

Over at SciFiScavenger on YouTube, I spend a half-hour chatting with host Jon Jones about plants, Usurpation, and my other books, and I share some recommendations for books I love.

Here’s the list — by the way, you can find more of my book opinions at Goodreads.

Life Beyond Us, edited by Julie Nováková, Lucas K. Law, and Susan Forest. The European Astrobiology Institute created this anthology of 27 short stories by top authors about first contact with life unlike our own. Each story is matched with an essay by a scientist. Exciting and educational.

Children of Time, by Adrian Tchaikovsky. If you liked Semiosis, you’ll like this. Similar theme, lots of spiders, and a transcendent ending.

Meet Me in Another Life, by Catriona Silvey. If you like romance novels, this is the science fiction novel for you. Two people keep meeting, but why? I wept like a baby at the ending.

Langue[dot]doc 1305, by Gillian Polack. If you like historical fiction, this is the science fiction novel for you. Scientists travel back in time to France in 1305, and they underestimate the people who live there. Worse, they don’t listen to the historian traveling with them.

Babel, by R.F. Kuang. As a translator, I found the magic system fascinating and meticulously constructed. Better yet, the story is solidly anchored in historical fact.

17776: What football will look like in the future, by Jon Bois and Graham MacAree. This is a daring multimedia SF experiment, and not really about football. I’ll never forget the tragic death of the heroic light bulb. Find it here: https://www.sbnation.com/a/17776-football

The Marlen of Prague: Christopher Marlowe and the City of Gold, by Angeli Primlani. Magic is the only thing that might save Europe from the Thirty Years’ War. The author clearly understands Prague and the theater.

In Defense of Plants, by Matt Candeias, PhD. How can you resist a book with an entire chapter about “The Wild World of Plant Sex”?

The Great Believers, by Rebecca Makkai. Not SFF at all, sorry, but I live in Chicago, and this novel accurately reconstructs the disaster of AIDS in the gay community in the 1980s. You might consider it historical fiction.

October 1, 2024

Deep Dish reading on Thursday

You’re invited to the Deep Dish speculative fiction reading on Thursday, October 3, at 6:30 p.m. at Volumes Bookcafe, 1373 N. Milwaukee Ave., Chicago, sponsored by the Speculative Literature Foundation. I’ll be one of the rapid-fire readers.

***

The launch of my novel Usurpation will be at 6:30 p.m. Wednesday, October 30, at Volumes Bookcafe. Everyone’s invited! More details here.

***

At Goodreads, I reviewed The Word, by JL George, a science fiction novel that shows how the power of compassion can fuel a rebellion in a dehumanized near-future Britain.

September 27, 2024

Hurricanes take a toll

In 2018 I was traveling as Hurricane Florence was hitting the East Coast. One morning I was in Michigan eating breakfast at a Best Western motel. I was up very early, and everyone else in the breakfast room was obviously a tradesman: construction site workers and truck drivers, strong men used to going from job to job and working with their hands.

Television screens on the walls played the CNN morning news, and when it ran a segment on Hurricane Florence, the room went silent and every man watched somberly. These men, or their friends and coworkers, might be called on to haul supplies and repair or rebuild the storm’s damage as their next job. They looked grim, not joyful, at the prospect of plentiful work. Those jobs would bring them face to face with loss and grief, and the future might be hard on their hearts as well as their hands.

September 25, 2024

Autographed copies of “Usurpation”

If you want an autographed copy of my next novel, Usurpation, and you won’t see me in person, you can order it through Volumes Books, a locally owned Chicago bookstore. The book comes out on October 29. International shipping can be arranged individually.

Find it at this link: https://volumesbooks.com/book/9781250809162

The official launch of the novel will be at 6:30 p.m. Wednesday, October 30, at Volumes Bookcafe, 1373 N. Milwaukee Ave., Chicago. Everyone’s invited! More details here.

September 18, 2024

Do your neglected houseplants want revenge?

Do your houseplants hate you? No, they don’t, no matter how much you neglect them. In fact, they’re praying to their green gods for your prosperity. They’ll struggle on as best they can, offering you beauty and silent non-judgmental companionship in exchange — they hope — for more-or-less regular watering and a spot near sunlight.

Plants need you, no matter how inconstant you are. A lot of the vegetable kingdom depends on animals, in fact, and plants haven’t always chosen well.

Consider this story of apples and oranges — osage oranges, to be exact.

First, the apple: colorful and tasty. Many animals love sugary treats. Apple trees make sweet fruit for us to munch on so we’ll throw away the core, and the seeds can germinate in a new place. (They don’t trust us much, though. They’ve made their seeds too bitter to eat so we’ll do our job right.)

How has this strategy worked out?

Apples originated in central Asia, and ancient peoples brought them east and west. When apples reached North America, they found a champion named John Chapman, “Johnny Appleseed,” who brought orchards to the United States frontier. In the 20th century, with more human help, the trees conquered large portions of Washington State. Now, 63 million tons of apples are grown every year worldwide, much of them in northern China.

From the apple trees’ point of view, it doesn’t get better than this. They grow worldwide and get lots of tender loving care. Human beings have served them very well.

In contrast, there’s the osage orange tree. It also produces fruit: green, softball-sized, and lumpy, full of seeds and distasteful latex sap. No one eats it. The tree originated in North America and once grew widely, but by the time European colonists arrived, its territory had shrunk to the Red River basin in eastern Texas. How did it fail?

The fruit had appealed to the Pleistocene’s giant ground sloth, a member of North America’s long-lost megafauna. The sloth scarfed them down, not chewing much, and the seeds traveled safely through its digestive system, emerging in new territory. Then, 11,000 years ago, human beings came to North America and couldn’t resist the allure of a couple of tons of meat per slow-moving beast. Giant ground sloths disappeared, and six of the seven species of osage orange also went extinct.

Why haven’t the remaining trees adapted their fruit to contemporary tastes? Because trees live for a long time, and 11,000 years ago for them is like the High Middle Ages for us. Lucky for them, humans find their wood useful and rows of the trees make effective windbreaks, so they currently grow across the United States and the world.

Still, useful wood isn’t much to offer the animal kingdom. Plants usually bribe us with food, the way that prairie grass entices grazers like bison to clear its domain of weeds. The bison nibble away weeds at the same time they munch on tasty grass leaves, which grass plants can easily replace. There used to be a lot more bison in North America, though. This strategy is starting to look shaky.

Flowering plants give bees nectar in exchange for hauling pollen from flower to flower, but bees seem to be having a rough time these days, too. If they go extinct, both wild and domestic plants are in deep trouble.

Plants find animal partnerships tempting. We’ll work hard for a fairly low price. But animals are unreliable and short-lived as individuals — and too often as entire species.

Back to your houseplants. Many of them likely originated in tropical rainforests. Your living room resembles a jungle: warm, reasonably humid, and moderately lit. Growing in confinement there isn’t such a bad life.

You, on the other hand, are fragile, distractible, hyperactive, and a bit murderous of your own kind as well as other species. Have your houseplants fallen into good hands? Can apples rely on us, and for how long? Are osage oranges one more extinction away from their own disappearance?

Your houseplants suffer from existential angst. Food is love, and so is fleeting beauty. They give their all for you. Go water them, offer reassurance, and consider what you owe to plants. You — and other species — need to be there for them now and in the future. Make them happy. Survive.

***

(This article originally appeared at the Tor/Forge blog .)

September 11, 2024

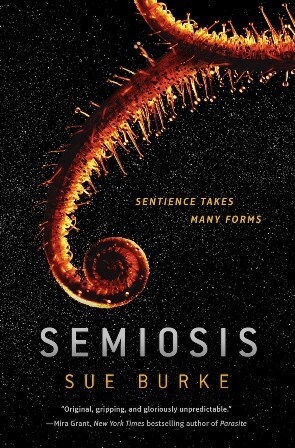

How I got the idea for the novel “Semiosis”

“Where do you get your ideas?”

If you’re a writer, you may have been asked that. Here’s how I got the idea behind Semiosis and turned it into a novel. Exactly how it happened isn’t typical, but it’s not unusual, either — there are a lot of paths to a novel, and they’re all good — but I think this story illustrates an essential and sometimes overlooked aspect of writing.

The whole thing started with the houseplants on my dining room table in the late 1990s. (The photo is from this decade: different house, different plants, but just as many of them.) One day, I discovered that the little pothos in a mixed planter had wrapped itself around another plant and killed it. At first, I blamed myself for not having noticed earlier and intervened. Then a philodendron on a bookshelf tried to sink roots into another plant. I became suspicious and did some research.

What I learned was disturbing. According to botanist Augustine Pyrame de Candolle, “All plants of a given place are in a state of war with respect to each other.” They compete for light and nutrients, and they use ingenious tactics to abuse and even kill each other. For example, roses have thorns so they can impale their prickles into other plants and climb over them. In the process, they might kill the other plants — but this is war. Roses don’t care as long as they’re victorious.

Even more disturbing, I learned, are the ways that plants use animals for a variety of tasks. They grow flowers to attract pollinators, as we all know, and they’re sometimes very unkind to hard-working insects. Plants also grow fruit so that we’ll eat it and spread their seeds. When a tomato (tomatoes are technically fruit) turns red, the tomato plant is sending you a message: Eat me now! We think we grow crops to feed ourselves, when from the point of view of many plants, they reward us with food to manipulate us into helping them survive. We serve the plants.

I wrote and sold a non-fiction article to a magazine about the viciousness of the vegetable kingdom, and as a science fiction writer, I thought I ought to do something more with the idea. But what was the story?

Then, at a science fiction writing workshop, the instructor posed a writing prompt about a special kind of wall that suddenly appears in a war zone. War? That might work. What if, on a distant planet, a human colony suddenly appeared like a wall between warring plant factions? (Two classmates also got good ideas from that prompt. One wrote a tender steampunk love story, and another an epic fantasy novel.)

Soon enough, my short story was written and published, dramatizing the dangers of setting up a colony between warring plants. A couple of years later, I came back to the story and thought about expanding it into a novel — so I began more research. Even a fairly Earthlike planet needs a carefully designed ecology.

A few unexpected details that I discovered during that research became critical. On Earth, most iron has sunk to the planet’s core, but a lot remains mixed in the crust, so iron is common. However, if a planet happens to have a lot of carbon as it is formed, almost all the iron sinks down to the core, and the crust becomes iron-poor. Plants need iron to create chlorophyll. Your blood is red from hemoglobin, which contains iron. You have what plants want. Stories need conflict. This one could be life-or-death.

I also realized that no matter how I tweaked the plants, they’d respond slowly. They’re simply low-energy beings. I needed to slow down the story but still keep it compelling. I decided to jump in time between chapters by skipping from one generation of the human colonists to the next, a kind of story called a roman-fleuve.

By then, I had finally developed the idea enough to begin writing — after spending a few years researching all the details.

Story ideas come from many sources: sometimes from a conversation, a news report, an old memory, an episode from history, a reaction to another story, a compelling prompt, or a random observation as you’re walking down the street. I believe that ideas are as easy to encounter as snowflakes in winter. What’s hard are stories. Ideas need to be dramatized. It may take time, observation, research — and possibly a little luck — to discover the drama behind the idea.

There’s no right or wrong way to find the drama. I can only offer one piece of advice: Be patient with the process.

***

(This article originally appeared in the Chicago Review of Books in February 2018.)

September 4, 2024

Books on sale!

If you or someone you know and love hasn’t read the novel Semiosis yet, the ebook will be on sale throughout the month of September for only $2.99 for Kindle. This promotion will include an excerpt from the third book in the Semiosis trilogy, Usurpation, which will be released on October 29.

Besides that, from September 4 to 6, Barnes & Noble is dropping the preorder price for Usurpation, as well as other preorders. B&N Members get 25% off, and Premium members get an additional 10% off. This is good for print, ebook, and audiobook editions.

Meanwhile, I’ll be at Chicago’s Printers Row Lit Fest on Saturday morning, September 7, at the Speculative Literature Foundation table. Come say hi!

August 28, 2024

Yellow

Every flower is unique. And yet, some small yellow flowers share a common nickname among botanists: DYCs, Damned Yellow Composites. Those are plants of the Asteraceae (daisy, aster, and sunflower) family, which are common worldwide. They’re usually tenacious weeds, and they may be pretty, but they can be so alike that they’re hard to tell apart.

Sometimes botanists don’t even try. It may not matter to the local ecology exactly which species those flowers belong to. Identifying them as DYCs serves well enough except for the most rigorous scientific purposes.

Every small songbird is also unique but far too many look similar to each other. The ones that are hard to distinguish are sometimes called dickybirds by birdwatchers, and often these birds — especially warblers — have a touch of yellow.

There are more galaxies in the sky than grains of sand on Earth’s beaches, so how many stars will be standard M-class yellow stars like our own Sol? Too many to count.

Flowers, birds, stars: yellow abounds. So does ambition.

Flowers, birds, and suns all strive for more, and our universe undergoes constant change as a result. Birds compete with song. Stars create more complex matter at every generation. Imagine what a weed will be like as eternity gives it time to perfect its art. The bouquets will astound us with their sheer ambition.

Yellow means aspiration and change — changes too small and slow for us to see, yet we can enjoy their success so far: a field of flowers, a morning filled with birdsong, and a sunny day. Yellow unites them with beauty.

August 21, 2024

“Life from the Sky” at Forever Magazine

My novelette “Life from the Sky” is included in the July 2024 issue of Forever magazine. The story tells how this isn’t a good time for an alien life form, no matter how simple and harmless, to land on Earth. The story was originally published in Asimov’s magazine in 2018.

Forever is a monthly science fiction magazine that features previously published stories you might have missed, edited by the Hugo and World Fantasy Award-winning editor of Clarkesworld Magazine, Neil Clarke. The July 2024 issue also includes “The Gods Have Not Died in Vain” by Ken Liu, and “Unauthorized Access” by An Owomoyela. Cover art by Ron Guyatt.

You can by it from Weightless Books: Forever Magazine Issue 114.

(Photo: Me trying to steal Neil Clarke’s Hugo Award at the 2024 Glasgow Worldcon.)

***

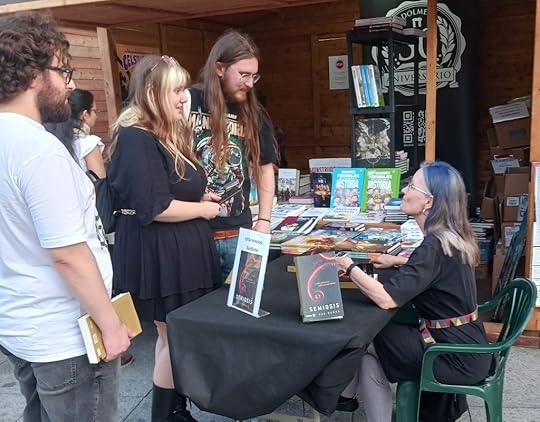

If you can read Spanish, you can buy the Spanish-language version of my novelette “Who Won the Battle of Arsia Mons?” [“¿Quién ganó la batalla de Arsia Mons?” translated by Virginia Sáenz] published in the anthology Excelsius 2024. I attended the Celsius 232 literary festival for science fiction, fantasy, and horror in Spain in July, where an anthology of works by writers attending the festival was created as a premium for its Patreon members. It is now on sale to the public, and it includes stories by Angela Slatter, Beatriz Alcaná, Cat Sparks, Charlie Jane Anders, Fulanito Pingüino Escritor, Guillem López, JV Gachs, María Zaragoza, Santiago Eximeno, and Thomas Olde Heuvelt.

“Who Won the Battle of Arsia Mons?” was originally published (in English) at Clarkesworld Magazine in 2017 (available there in print and in audio). It tells the story of the stupidest thing I could think of for robots to do on Mars.

(Photo: Meeting readers at Celsius. The festival was full of people eager to read!)