Sue Burke's Blog, page 5

December 18, 2024

The killers will thank you for it

Pragmatics is a branch of linguistics concerned with the relationship of words and sentences to the environment in which they occur. We might also call this context. Machines can’t grasp pragmatics and context — not Google Translate, not ChatGPT, or anything like them. Machines and artificial intelligences don’t interact with the real world. Nothing means anything to them.

I recently made the mistake of reading the text on a sprayer bottle as I was misting a few of my house plants. The text came in English and Spanish. I understand both languages, and I saw errors. Worst of all, this error, which no human would make:

Weed Killers (Deshierbe a Asesinos)

The Spanish version does, in fact, mean “Weed Killers” in the sense of “Go weed the killers” or “You must pull out the weeds on assassins.”

It should say:

Weed Killers (Herbicidas)

As a human being, I can only laugh. Or weep. When the robots take over, they’re going to make so many mistakes…

December 11, 2024

Using all the senses in writing

Using sensory details makes writing more vivid so that readers can see, hear, feel, taste, and smell what’s happening in a story.

Naturally, it’s a little more complicated than that.

First of all, we have more than five senses. Vestibular sense involves movement and balance. Proprioception is also called body awareness and tells us where our body parts are in relation to each other and how to do things, like pick up a heavy rock or delicate egg. Chronoception lets us sense the passage of time. We can also sense temperature and pain.

This article at John Hopkins University Press says there are nine senses. An article at the University of Utah Genetics Science Learning Center says there are twenty, but it counts some senses in other animals. That might be useful if we’re writing about non-humans.

The things that we sense are interpreted through our thoughts and emotions, too.

As writers, how do we use these senses in a story? The correct answer to this and many other questions is: It depends. What’s the story you want to tell? What matters to the characters in it? What is the pace you want? Romance novels tend to be lush, and a mystery might be spare, and in either case, the senses that you evoke will guide the attention of the reader to what matters. An intriguing whiff of perfume at a party with contrasting notes of candy-like violets and earthy sandalwood might signal the start of an affair. A barking dog might make Sherlock Holmes deduce.

When we write, it’s best to go directly to the sensation. A bad example: Becky smelled acrid smoke and knew it would be toxic. Instead, this: The smoke reeked of acrid toxins. The reader will know that Becky was smelling it and recognized the smell. Fewer words are always better than more words, too.

Next, why do these particular sensory details matter? An article by Donald Maass, “Moving Along” at Writer Unboxed, shows how to use sensory details to evoke emotion. I’m going to disagree with him, though. He says the final example is “focusing not on visualizing, sensory details,” but I say it is. Count the colors mentioned. Note the things we could taste and feel, especially the dryness. Consider the snippets of conversation we hear. It gives us the full picture with plenty of vivid sensory details in an unselfconscious way by showing us how these things matter.

***

(Art: stick figure by Core5ivpro .)

December 4, 2024

“The Coffee Machine” at Clarkesworld

My translation of the short story “The Coffee Machine” by Spanish author Celia Corral-Vázquez has just been published at Clarkesworld Science Fiction and Fantasy Magazine!

A coffee vending machine acquires consciousness, then things go ridiculously wrong. I giggled as I translated it, and I hope I got all the jokes.

November 27, 2024

I saw rainbows everywhere at night

What I saw wasn’t real and no one else could see it, and it was gorgeous.

I recently had a cataract-clouded lens in my eye removed and replaced with an artificial lens. I can see much better now.

But there’s something I can no longer see. My cataracts were the type that made halos around bright light, and these halos were like rainbows or glories. Walking down a street at night was a spectacle. The photo might give you an idea of what it was like.

I won’t miss the cataracts and the problems they caused, but I will miss the beautiful illusion of rainbows.

November 20, 2024

Don Quixote vs. science fiction

When I lived in Spain, I soon noticed that Miguel de Cervantes and his most celebrated novel, Don Quixote de la Mancha, permeated the culture. Think of Shakespeare in English-speaking realms, then dial it up to 11.

The book changed the way Spain thought about itself. It also made Spain reject any sort of non-realism in fiction, such as science fiction and fantasy, for centuries to come.

Published in 1605, Don Quixote tells the story of a poor, elderly nobleman driven mad by the fantasy novels of his day, which depicted brave knights and their dazzling deeds. The nobleman adopts the name Don Quixote and sets off on quests. In chapter VIII he famously mistakes windmills for terrible giants and attacks them. In chapter XLI, he is tricked into believing that an enchanted wooden horse has the power to carry him and his squire Sancho Panza through the sky. (Photo: Engraving from an 1863 edition of Don Quixote by Gustave Doré.)

Cervantes’s novel was written when Spain was in a period of desengaño or “disillusionment” after imperial losses, government bankruptcy, a deadly plague, failed harvests, economic disaster, and the defeat of the Invincible Armada. The nation had attempted to fulfill grand ambitions only to discover that it had been tilting at windmills. The novels that Cervantes’s fictional character read were real books that had, a generation earlier, inspired the conquistadors in their exploits: the state of California is named after an imaginary caliphate in one of those books, The Exploits of Esplandian, which was the sequel to Amadis of Gaul (which I translated here). Ambition was not enough, though, and eventually fantasy gave way to sad reality.

Don Quixote changed the way Spain thought about itself — and about literature.

“The problem with Spanish science fiction starts with Quixote,” the editor of a Spanish science fiction ‘zine told me. “Of course, it was a satire of the fantasy adventure novels of its day, and ever since then, perhaps because the satire was so biting, Spain has been the home of realism in fiction.”

School children were taught to scorn those novels of chivalric quests, speculation, and mysterious unknown lands, if they were taught about them at all. Still, a few writers always experimented with science fiction and fantasy, and in the 20th century, books from outside Spain began to inspire a generation.

“Fantastic” literature — science fiction, fantasy, and horror — was slow to gain acceptance as worthy, but in the 1980s and 1990s a growing number of authors encouraged each other and carved out a niche that has since flourished. In the 21st century, books like the Harry Potter and Twilight series appealed to massive numbers of young readers, to the surprise of established publishers and to the delight of the small publishers who had taken a chance on those novels and cashed in. All kinds of publishers took note. The ranks of fandom grew.

Just as in the English-speaking world, Spanish “mainstream” literature discovered it could no longer control access to respectability. Readers had their say.

November 6, 2024

I’ll be at Windycon this weekend

I’m attending Windycon this weekend, Chicagoland’s longest-running science fiction convention. This is its 50th year, and it will be held from November 8 to 10 at the Double Tree Hilton Hotel in the suburb of Oak Brook. This year’s theme is Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations.

With about 1,000 members, this is a more personal and friendly event than mega-conventions. Note the word “members” — the convention is organized by fans for fans, all volunteers, not by a professional corporation. It also has a literary bent, focusing on experienced and aspiring authors and writers. Topics for panels and activities range from astrophysics to costuming techniques to pop culture. This includes steampunk, dragons, fairies, robots, music, anime, zombies, pirates, ninjas, extraterrestrials, gaming, horror, space operas, urban fantasy, theater, vampires, time travel, and cats.

There’s also an art show, dealer’s room, gaming room, and legendary parties at night.

During the day, here’s where you can find me:

Early SF Authors and the Pseudonyms They Hid Behind — Friday, 6 to 7 p.m., Windsor Room. How would their work have been affected if they were allowed to show who they were? Panelists are Richard Chwedyk, Steven Silver, and W.A. Thomasson; moderator Sue Burke.

Writer’s Workshop — Saturday, 9 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. Preregistration required.

Author Reading — Saturday, 12 to 12:30 p.m., Ogden Room. I plan to read the essay “Do your neglected houseplants want revenge?” and the short story “Summer Home.”

Reading and Writing Through the Female Gaze — Saturday, 2 to 3 p.m., York Room. Panelists are Lisa Moe, Dina S. Krause, K.M. Herkes, and Alexis Craig; moderator Sue Burke.

The Many Facets of Fandom — Saturday, 8 to 9 p.m., Butterfield Room. How you experience the different brilliant sparkles depends on how you cut the gem that is fandom. Panelists are Jason Youngberg, Alexis Craig, and W.A. Thomasson; moderator Sue Burke.

Familiar or Fantastical? — Sunday, 10 to 11 a.m., Kent Room. What type of world-building do you enjoy with your fiction? Do you prefer far-off worlds or ours? Panelists are David Hankins and Sue Burke; moderator Bill Fawcett.

The Darker Side of Space — Sunday, 11 a.m. to 12 p.m., Hunt Room. The future is not always a garden of roses. Let’s discuss the darker side of science fiction futures. Panelists are Donna J.W. Munro, Chris Gerrib, and Paul Hahn; moderator Sue Burke.

October 30, 2024

AI is Fueling a Science Fiction Scam

Can an AI write a good short story? No. But some people are submitting AI-produced stories for publication anyway, hoping for a quick buck. For science fiction magazines, this is costing them time, money, and morale.

I wrote about the problem and the lack of easy solutions for an article in the current issue of Chicago Review of Books, AI Is Fueling a Science Fiction Scam That Hurts Publishers, Writers, and Even Some of the Scammers.

October 29, 2024

On sale now (finally!): Usurpation

Today the novel Usurpation goes on sale! You can buy it wherever fine books are sold, available as hardcover, ebook, and audiobook. Find out why carnivory isn’t the worst thing a plant can do.

It’s the third book in the Semiosis trilogy, and here’s an incisive review of the series at Ancillary Review of Books by Alex Kingsley called “Imagining Radical Mutualism.”

If you’re in Chicago, please come to the book launch tomorrow, Wednesday, October 29, at 6:30 p.m. at Volumes Bookcafé, 1373 N. Milwaukee Ave. Since it’s the day before Halloween, feel free to wear a costume! (Don’t worry, you won’t be the only one.) If you’re not in Chicago and you want an autographed copy, you can order it through Volumes.

October 23, 2024

Usurpation: Love will be ferocious

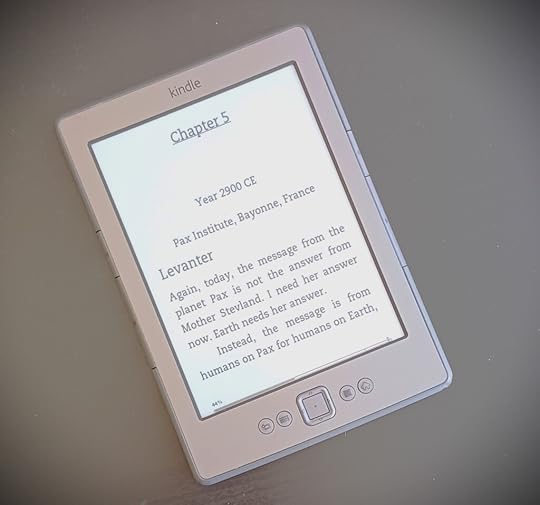

The novel Usurpation is the third in the Semiosis trilogy. The first book, Semiosis, takes place on a distant planet called Pax where the dominant species is an intelligent plant, rainbow bamboo. Stevland is the reigning bamboo. At the end of the second book, Interference, Stevland has sent his seeds to Earth, where the rainbow bamboo are flourishing, but no one knows they’re intelligent.

Then, at the end of Interference, Stevland sends a message to the bamboo on Earth: “…I must share a secret about humans. They are ours to protect and dominate.”

A bamboo named Levanter asks, “Tell us how.”

Stevland’s response finally arrives in Usurpation: “…Compassion will give you courage. Love will be ferocious.”

That’s all I can say without spoilers. In fact, I’ve probably spoiled enough already.

Usurpation will be released on October 29. I’ll be celebrating at 6:30 p.m. Wednesday, October 30, at Volumes Bookcafé, 1373 N. Milwaukee Ave., in Chicago, with Alex Kingsley, whose first novel, Empress of Dust , has just been released. You’re invited! It’s the day before Halloween, so you’re encouraged to cosplay.

You can see me at a Speculative Literature Foundation event read the opening of Chapter 3 of Usurpation in this 3-minute video. (All the novels in the trilogy are available as audiobooks, narrated by Caitlin Davies and Daniel Thomas May, who do a much better job than me.)

You can read a few reviews of Usurpation at NetGalley, and a recent review of Semiosis at Space Cat Press. Semiosis was named one of the 75 best science fiction books of all time by Esquire Magazine.

If you want an autographed copy of my next novel and you can’t come to the launch party, you can order it through Volumes Books here.

October 16, 2024

The novel that changed Spanish science fiction

I was thrilled when I learned that Rafael Marín would translate my novel Semiosis into Spanish. I think he’s one of the finest stylists in genre writing in Spain. But he’s more than that. He’s an award-winning novelist, comic book writer, essayist, critic, screenwriter — and a pioneer in the genre.

His first novel, Lágrimas de luz [Tears of Light], is often called the “before and after” novel in Spanish science fiction. Published in 1984 and written when Marín was only 22 years old, it proved that a Spanish author could write an ambitious literary work of science fiction.

This might sound odd. Of course Spanish authors could — but they had to believe that themselves, and they had reason to doubt it. For the previous two centuries, realism and naturalism had reigned supreme in Spanish literature. Despite “futurist” authors like Nilo María Fabra, science fiction (and fantasy and horror) didn’t exist in Spain and wasn’t possible.

In the English-speaking world, science fiction set down its roots in the early 20th century, first as pulp and then as more serious works. Spain had its pulp too, starting in the 1950s, although its authors usually wrote under Anglo-Saxon pseudonyms like Louis G. Milk or George H. White at the behest of publishers, who did not think openly Spanish authors, pulp or serious, would sell. Top English-language authors like Alfred Bester and Roger Zelazny were available in translation, though, and they made their mark.

From 1968 to 1982, a fanzine with a professional attitude, Nueva Dimensión, edited by Domingo Santos, provided budding authors with a chance to grow, and some solid works began to appear. But nothing caught readers’ attention like Lágrimas de luz.

The novel’s plot

The novel is set during the Third Middle Ages. A young man named Hamlet Evans, living in a small town that manufactures food, aspires to more in life than toiling in a factory, numbed by drugs and sex. He wants to be a poet, specifically one of the bards whose songs celebrate the Corporation, which expands the human empire and protects it from its enemies. He is accepted for training at the bards’ monastery and is assigned his first military ship.

Soon he learns that the glorious triumphs of the empire are anything but: Indigenous life forms are cruelly wiped out and the planets’ resources are stripped as the Corporation expands its iron grasp. Disillusioned, Hamlet can no longer compose acceptable epic poems.

He resigns and is set down on the first available planet, which turns out to be under punishment for a rebellion against the Corporation. He barely survives, eventually escaping to join a small theater group and then a circus. The Corporation, meanwhile, decides that no entertainment that fails to extol its greatness can continue to exist, and sends troops to wipe them out.

Hamlet escapes again, and he decides to continue an outlaw artistic existence to defy the Corporation.

Ambitious and Spanish

Marín himself has called the novel an “ambitious space opera” — which it is, offering careful characterization and thematic development. Hamlet matures as a man and an artist in a fully-imagined universe.

The novel also makes a clean break from pulp. It features a protagonist who is hardly a hero, and its themes include the search for beauty as well as the crisis and alienation of youth. Rather than save the universe, Hamlet can barely save himself, and the universe might not even merit saving: no lightweight escapism here.

The story also draws on Spain’s own medieval past and brings it into the future. The bards’ songs echo works like El Cid that had once been sung throughout the land — a past oral culture updated for the novel’s present. The novel also responds in its own way to Robert Heinlein’s Space Troopers and openly draws on themes from Moby Dick and other classics.

The surprise of Lágrimas de luz didn’t usher in a sudden boom in Spanish science fiction. That came in the 1990s with works by authors like Juan Miguel Aguilera, Elia Barceló, Javier Negrete, and Rodolfo Martínez, among many others, but the door had been opened.

Lágrimas de Luz, by the way, is still in print after all these years and is available from Spain’s Apache Libros.