Sue Burke's Blog, page 49

September 6, 2017

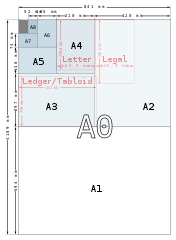

A4 versus Letter paper

If you do business internationally – such as, in my case, translating – you soon become aware that the world generally uses two sizes of paper. There are bigger international annoyances than this, such as getting paid across borders, but this petty nuisance deserves some attention. Why do two competing paper sizes even exist?

If you do business internationally – such as, in my case, translating – you soon become aware that the world generally uses two sizes of paper. There are bigger international annoyances than this, such as getting paid across borders, but this petty nuisance deserves some attention. Why do two competing paper sizes even exist?For those blissfully unaware of the issue, here’s the problem:

• The most frequently used paper size in the world for business purposes is A4, measuring 210 by 297 millimeters (8.27 in × 11.7 in). It originated in Europe.

• Letter, also called US Letter, is the common paper size commercially used in the United States, Canada, Mexico and the Dominican Republic. It measures 8.5 by 11.0 inches (215.9 mm by 279.4 mm).

No one knows how Letter size started, but the American Forest & Paper Association believes it goes back to the days of manual paper-making. A paper-maker created a page as long and wide as his arms could reach. The page was later trimmed into quarters, so a page is one-fourth of the span of a man’s arms.

Europeans, however, can explain exactly why A4 paper is that size. In the late 1700s, scientists created an ingenious series of sizes of paper. It starts with a meter-square sheet, which is then cut in half with an aspect ratio involving the square root of 2. It has technical advantages for scaling printed material to make it fit a larger or smaller standard-size sheet.

This discovery was briefly used in France, then forgotten for more than a century, when Germans reinvented the meter-and-√2 system.

What’s interesting is that both A4 and Letter became standards at about the same time. The international zeitgeist was striving for efficiency.

Germany adopted the A4 system in 1922. It slowly began to be adopted by other countries, and in 1975 it became an ISO (International Organization for Standardization) standard.

The Letter size became an industry standard in the United States in 1921. For a time, the federal government used a slightly smaller size, but it adopted the Letter size during the Reagan administration – there’s something to thank him for. In 1992, the American National Standards Institute defined it as an official standard.

Why two standards? Why couldn’t the same standard have been adopted in the early 1920s all over the world?

It’s hard for us now to imagine how isolated Europe and North American remained from each other in the 1920s. Airplanes could barely cross the Atlantic Ocean. Radio operators had just begun to talk to each other. Ships took more than a week to cross the ocean in good weather. The two continents didn’t need the same standard.

Now, the internet unites the world with sometimes distressing immediacy. Would a single standard make sense now? Yes. But I think computers may actually make a single standard less likely. I can type up a document in Letter, then push a button and convert it to A4 instantly with no muss or fuss. (Except for MS Word documents. In that program, altering the least little thing may cause a meltdown.)

So here we are and here we may stay. Seen from space, the world is a single beautiful blue marble in the heavens. On the ground, we can’t even agree on what size a sheet of paper should be. But we needn’t live alike to love alike.

The 20th century faced the challenge of standardization with reasonable success but failed disastrously with the challenge of world peace. The 21st century could make peace a worldwide standard. Translators are standing by to help word by word.

………

Here are some links to learn more about this fascinating subject:

This article delves deep into paper size specifications, including where to punch holes for filing purposes and how big the holes should be. Yes, of course, there are rules about that.

And Now You Know: “A4 versus US Letter - Battle of the paper sizes” is a 4:15-minute YouTube video that praises the A4 size and its mathematics. It closes by addressing President Trump: “Do you want to make America great again? Adopt ISO-216 (and while you're at it, check out the metric system too!).”

My friend, we can barely restrain him from blowing up our health care system or North Korea. You ask for too much.

Ars Technica offers an entertaining but pointless debate – except for the following quote: “Letter is 93.5 square inches of space, while A4 has 96.67 square inches of space. That extra four square inches probably never saved anyone’s ass, but it can’t hurt either.”

As often happens with Wikipedia, this article explains paper sizes in greater detail than you may ever need to know, although the charts are lovely. And here’s everything to know about the US Letter size.

Finally, check out “A4 and Before: Towards a long history of paper sizes,” by Robert Kinross. It is indeed a long history going back to the Middle Ages, although he only explains A4 paper. This 30-page PDF is taken from a lecture given at the National Library of the Netherlands.

— Sue Burke

Cross-posted at my professional writers website.

Published on September 06, 2017 08:28

August 31, 2017

Advance Reader Copies of “Semiosis”

The ARCs of my novel Semiosis have arrived from Tor!

I’ve already sent a few out. The book itself comes out in February, and you can pre-order it at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

(The doily, by the way, was made by my great-grandmother, and is protected by a tabletop plexiglass sheet. The plant is an Oxalis, also called a shamrock plant, although it’s not a real shamrock.)

— Sue Burke

Published on August 31, 2017 07:55

August 28, 2017

How big is the flood?

The flood in southeast Texas has been described as the size of Lake Michigan. To help visualize that, here’s a picture I took of Lake Michigan this morning at Contemplation Point in Lincoln Park, Chicago. The horizon is 4 or 5 miles away. Lake Michigan is 118 miles across at its widest and 307 miles long.

-- Sue Burke

Published on August 28, 2017 12:50

August 22, 2017

“...we shall never surrender...”

This weekend I saw the movie Dunkirk. In case you haven’t heard, it depicts the 1940 evacuation of British soldiers from the beach at Dunkirk in France as Nazi troops overran the area. The Nazis attempted to block the evacuation every way they could. Eventually, more than 300,000 men were rescued, but 68,000 were killed, wounded, missing, or captured.

This weekend I saw the movie Dunkirk. In case you haven’t heard, it depicts the 1940 evacuation of British soldiers from the beach at Dunkirk in France as Nazi troops overran the area. The Nazis attempted to block the evacuation every way they could. Eventually, more than 300,000 men were rescued, but 68,000 were killed, wounded, missing, or captured.The movie depicts the battle with continuous, terrifying action.

Because so many warships and other vessels were sunk or damaged and the evacuation was so desperate, Britain pressed 850 small civilian craft, such as yachts and motorboats, to help. The movie focuses on the attempt of one soldier to get to safety in Britain, one small craft that comes to the rescue, and two Spitfire airplane pilots fighting to protect the ships.

We see no Nazis in the movie, just the death and destruction they cause. But Nazis are in the news these days, and it may be a good time to remember, as the movie does, what Prime Minister Winston Churchill had to say after Dunkirk:

“Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender…”

— Sue Burke

Published on August 22, 2017 07:34

August 19, 2017

wronghands1.files.wordpress.com

wronghands1.files.wordpress.com Posted by Sue Burke on 19 Aug 2017, 14:46

Published on August 19, 2017 08:15

August 18, 2017

Black Gate Articles Yes, The Civil War Was About Slavery (The Confederates Said So)

Black Gate Articles Yes, The Civil War Was About Slavery (The Confederates Said So)In June of 1902, former Confederate cavalry raider John Singleton Mosby wrote to his friend Judge Reuben Page about the war that had given him his fame, bemoaning the fact that the causes of that war were already being lost in the public’s consciousness.

Posted by Sue Burke on 18 Aug 2017, 22:44

Published on August 18, 2017 16:11

Opinion | How to Make Fun of Nazis

Opinion | How to Make Fun of NazisDon’t respond to fascists with violence. A German town offers some helpful tips.

Posted by Sue Burke on 18 Aug 2017, 21:58

Published on August 18, 2017 15:11

August 17, 2017

FACT CHECK: General Pershing on How to Stop Islamic Terrorists

FACT CHECK: General Pershing on How to Stop Islamic TerroristsGen. John J. Pershing did not effectively discourage Muslim terrorists in the Philippines by killing them burying and their bodies along with those of pigs.

Posted by Sue Burke on 17 Aug 2017, 19:56

Published on August 17, 2017 13:06

Leaving “Medieval” Charlottesville

Leaving “Medieval” Charlottesville</diA call to action in the wake of Charlottesville to re-enactors, LARPers, and all who enjoy the Middle Ages casually. Part XXIX in our ongoing series on�Race, Racism and the Middle Ages,�by Paul B. Sturtevant.

Posted by Sue Burke on 17 Aug 2017, 17:21

Published on August 17, 2017 10:35

The 2005 annular eclipse

In 2005, I was living in Madrid, Spain. Here’s my blog post from that year’s eclipse. The map below from the Planetarium of Pamplona, Spain, shows Universal Times, and the Madrid peak time was 10:58 a.m. Luckily, I still have my Eclipse Shades to witness next week’s eclipse here in Chicago. Many suppliers are sold out already.

This morning, October 3, was cool and cloudless. My husband and I were sitting on the grass next to some rose bushes at the esplanade of Madrid's Planetarium. More than 2,000 people had come to witness the first annular eclipse of the Sun visible in Spain since April 1, 1764. It was about 10:30 a.m., still 25 minutes away from the big moment, but the Sun already had become a remarkable crescent.

One of the young women sitting behind us looked up. “¡Ay! ¡Qué chulo!” she said to her friend: Wow! It's so neat!

An LED screen in front of the Planetarium offered a live view of the Sun, or from time to time, explanatory videos. The orbit of the Moon placed it a bit far away from the Earth at that moment, so it wouldn’t cover all of the Sun as it does during a total eclipse. People on the ground in a narrow band from Spain to Somalia would see it cover 90% the Sun and create a ring of light in the sky.

Of course, no one should look at the Sun directly, so the Planetarium gave away 1,600 Eclipse Shades™, cardboard glasses with plastic lenses so dark nothing dimmer than the Sun could be seen through them. Someone had put a pair on the statue of the late, beloved Madrid Mayor Enrique Tierno Galván that presides over the esplanade, and groups of friends photographed each other standing beside it, everyone in their Shades.

Other people held the glasses as an improvised filter over the camera lens of their mobile telephones. More professionally minded photographers, there in abundance, used real filters. School groups, retirees, but most of all young people had come out: unemployment is high among young adults in Spain, so they had the time and the proper finances to appreciate a free show.

Refreshments, so to speak, were provided by Wrigley's, which introduced a new brand of chewing gum that day to Spain: Trex Eclipse. Representatives handed out free packs. The advertising campaign called the gum “intensely refreshing.” It tasted very minty.

Over loudspeakers, an astronomer described other eclipses as the heavens continued to move above us. By 10:45 the light was noticeably dimmer, like a cloudy day, and, next to us, the light diffracting through the tiny spaces between the leaves of the rose bushes dappled tiny crescent shapes on the ground.

A Telemadrid TV station helicopter began to circle the Planetarium, photographing a sea of people staring through cardboard glasses at the sky. Some people waved.

The moment approached. The crescent shrank into a tiny sliver.

The Planetarium had arranged for a violinist, Ara Malikian, to play his composition, Moon Shadow, during the peak minutes of the eclipse. He was introduced to applause. The work made use of the ability of a violinist to play two strings at once, the two notes representing the two heavenly bodies as they reached harmony — though he was hard to hear over the TV helicopter.

The Moon kept moving, and, finally, to more applause and shouts of “¡Vamos!” All right!, it made a ring out of the Sun.

For 4 minutes and 11 seconds, a beautiful halo of light floated overhead, too brilliant to see without shades, wonderful but weird. The shadows under the rose bushes became rings. The light was dimmer, and shadows sparkled with a new geometry. People looked up and around with delight.

Then, the ring thinned at the bottom, and there was a flash of a Baily's bead, a pearl of light that marked the rays of the Sun passing through a valley on the edge of the surface of the Moon. The Sun became a crescent again, to more applause.

The violinist explored the slow separation of the two spheres, ending with two sustained, simultaneous notes, to yet more applause. The crescent gradually grew, and eventually people began to drift off to the street, pausing for one last observation of the Sun through their souvenir glasses before they entered the subway and returned to their normal Monday routine.

— Sue Burke

This morning, October 3, was cool and cloudless. My husband and I were sitting on the grass next to some rose bushes at the esplanade of Madrid's Planetarium. More than 2,000 people had come to witness the first annular eclipse of the Sun visible in Spain since April 1, 1764. It was about 10:30 a.m., still 25 minutes away from the big moment, but the Sun already had become a remarkable crescent.

One of the young women sitting behind us looked up. “¡Ay! ¡Qué chulo!” she said to her friend: Wow! It's so neat!

An LED screen in front of the Planetarium offered a live view of the Sun, or from time to time, explanatory videos. The orbit of the Moon placed it a bit far away from the Earth at that moment, so it wouldn’t cover all of the Sun as it does during a total eclipse. People on the ground in a narrow band from Spain to Somalia would see it cover 90% the Sun and create a ring of light in the sky.

Of course, no one should look at the Sun directly, so the Planetarium gave away 1,600 Eclipse Shades™, cardboard glasses with plastic lenses so dark nothing dimmer than the Sun could be seen through them. Someone had put a pair on the statue of the late, beloved Madrid Mayor Enrique Tierno Galván that presides over the esplanade, and groups of friends photographed each other standing beside it, everyone in their Shades.

Other people held the glasses as an improvised filter over the camera lens of their mobile telephones. More professionally minded photographers, there in abundance, used real filters. School groups, retirees, but most of all young people had come out: unemployment is high among young adults in Spain, so they had the time and the proper finances to appreciate a free show.

Refreshments, so to speak, were provided by Wrigley's, which introduced a new brand of chewing gum that day to Spain: Trex Eclipse. Representatives handed out free packs. The advertising campaign called the gum “intensely refreshing.” It tasted very minty.

Over loudspeakers, an astronomer described other eclipses as the heavens continued to move above us. By 10:45 the light was noticeably dimmer, like a cloudy day, and, next to us, the light diffracting through the tiny spaces between the leaves of the rose bushes dappled tiny crescent shapes on the ground.

A Telemadrid TV station helicopter began to circle the Planetarium, photographing a sea of people staring through cardboard glasses at the sky. Some people waved.

The moment approached. The crescent shrank into a tiny sliver.

The Planetarium had arranged for a violinist, Ara Malikian, to play his composition, Moon Shadow, during the peak minutes of the eclipse. He was introduced to applause. The work made use of the ability of a violinist to play two strings at once, the two notes representing the two heavenly bodies as they reached harmony — though he was hard to hear over the TV helicopter.

The Moon kept moving, and, finally, to more applause and shouts of “¡Vamos!” All right!, it made a ring out of the Sun.

For 4 minutes and 11 seconds, a beautiful halo of light floated overhead, too brilliant to see without shades, wonderful but weird. The shadows under the rose bushes became rings. The light was dimmer, and shadows sparkled with a new geometry. People looked up and around with delight.

Then, the ring thinned at the bottom, and there was a flash of a Baily's bead, a pearl of light that marked the rays of the Sun passing through a valley on the edge of the surface of the Moon. The Sun became a crescent again, to more applause.

The violinist explored the slow separation of the two spheres, ending with two sustained, simultaneous notes, to yet more applause. The crescent gradually grew, and eventually people began to drift off to the street, pausing for one last observation of the Sun through their souvenir glasses before they entered the subway and returned to their normal Monday routine.

— Sue Burke

Published on August 17, 2017 08:40