Roxanna Elden's Blog, page 17

September 7, 2015

See Me After Class: Discussion Questions for First-Year Teachers

Discussion and Reflection Questions for First-Year Teachers

See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers

By Roxanna Elden

General Questions

The author mentions teacher movies several times in her book. In what ways does she seem think these movies are helpful to real-life teachers? In what ways does she suggest they hurt? Do you agree?

Which chapter did you find the most helpful? Why?

Which chapters would you recommend to someone who hasn’t started teaching yet? Which are more helpful after a few months in the classroom? Explain.

Chapter-by-chapter questions:

What this Book is… and is Not

In the first chapter of the book, the author addresses the three types of books on the market for new teachers: Professional development, inspirational stories, and general guidebooks. What does she say are the weaknesses of each type of book? Do you agree?

Ten Things You Will Wish Someone Had Told You

Which of the advice in this chapter had you heard before you started teaching? Which lessons have you had to learn on the job? Do you agree with this advice?

First Daze

In this chapter, the author lists and answers frequently asked questions about the first day of school. What were you most worried about as you approached your first day as a teacher? Were you worried about the right things?

Maintaining and Regaining Your Sanity, One Month at a Time

Chapter four charts the morale of teachers at different points in the school year. Do you find that your own morale followed this pattern? Explain.

Piles and Files: Organization and Time Management

In this chapter the author talks about her own struggles with organization, and shares the filing systems she eventually developed to deal with the inflow of paperwork. Did you have a system for staying organized at the beginning of this year? Has that system held up over the course of the year? If so, what suggestions can you offer others? If not, what changes might you make in time for next year?

Your Teacher Personality: Faking it. Making it

This chapter suggests building a teacher personality that rests on personal strengths and works around weaknesses. What personal strengths have helped you as a teacher? In which areas do you think you need the most work? In what ways can you (or do you) use your personal strengths to work around weak areas?

Classroom Management: Easier Said Than Done

In this chapter, the author details potential pitfalls in management principles like consistency and positive reinforcement. Have you had any experiences in which common management wisdom fell short? How did you deal with these situations and what did you learn from them?

Procedures that (Probably) Prevent Problems

Chapter eight suggests that readers “beg, borrow, and steal” classroom procedures from other teachers, “… then adapt” those procedures to their own classroom. Have you ever tailored another teacher’s ideas to fit your own classroom? What procedures have you observed in the classrooms of other teachers that might work in your own classroom? What details will you change to make the ideas work considering your personality, age group, and subject area?

The Due Date Blues: When High Expectations Meet Low Motivation

Here the author talks about the heartache of watching students miss major assignments. Has this happened to you this year? How did you handle it? What do you plan to in the future to encourage student responsibility?

No Child Left… Yeah, Yeah, You Know

In chapter 10, the author discusses difficulties with individual students. She also says that many teachers have a specific type of student in mind when they choose their career, and are sometimes more effective with their favorite type of student. Which students were easiest for you to connect with this year? Which were the most difficult? What can you do to connect better with these students in the future?

Parents: The Other Responsible Adult

Chapter eleven includes many stories involving difficult parents, but the tone of the last two stories is different. Why do you think these stories were included? What helpful advice have you heard about dealing with parents?

The Teachers’ Lounge: Making it Work with the People You Work With

Chapter twelve describes difficult types of coworkers, including those who are overly negative, but also those who are positive to the point of bragging. Is there such thing as too much positivity? What do you believe is the proper balance between positive and negative when teachers talk about work?

Please Report to the Principal’s Office

Chapter thirteen discusses actions by administrators that make teachers’ jobs harder. How can teachers work with or around administrators who do these things?

Stressin’ About Lessons

Here, the author discusses reasons that seemingly well-planned lessons go wrong. Has this ever happened to you? How did you handle it? What activities might you use if left with extra class time after a lesson?

Observation Information

There are two schools of thought about dealing with observations: “Always teach like you are going to be observed,” and “the dog and pony show.” What are some potential pitfalls of each of these ways of thinking? At your school, are you expected to stay ready for company, or prepare your best sample of teaching for scheduled observations?

Testing, Testing

Chapter sixteen deals with the unintended consequences of high-stakes testing. Which of the consequences mentioned in this chapter have you experienced? How can teachers balance creativity and hands-on learning with the increasing demand for test preparation?

Grading Work Without Hating Work

Which of the grading tips in this chapter were helpful? What other strategies do you use to keep up with grading? What strategies do you plan to use in the future?

Moments We’re Not Proud Of

In chapter eighteen, teachers share their low-points. Which of these stories did you find most memorable? Were there any stories that other teachers shared this year that you found especially helpful?

Dos and Don’ts for Helping New Teachers In Your School

In this chapter, the author comes down hard on teachers who say things like, “That would never happen in my class.” What do you believe are the qualities of a good mentor teacher? Who do you turn to for teaching advice and why?

Making Next Year Better

What are the main lessons you will take away from this book? How do you think you might have reacted differently to the book if you read it before, rather than after, your first year as a teacher?

See Me After Class: Book Discussion Questions for Education Courses and Pre-Service Teachers

Professors… or anyone using See Me After Class to train pre-service teachers:

This chapter-by-chapter guide is specifically tailored to readers preparing for the first year of teaching, which leaves you more time to develop that lesson on Bloom’s Taxonomy.

See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers

Chapter-by-Chapter Discussion Questions for Education Majors and Pre-Service Teachers

What this Book is… and is Not

In the first chapter of the book, the author addresses the three types of books on the market for new teachers: Professional development, inspirational stories, and general guidebooks. What does she say are the weaknesses of each type of book? Do you agree?

Ten Things You Will Wish Someone Had Told You

Which of the advice in this chapter have you heard before? Do you agree with this advice?

First Daze

In this chapter, the author lists and answers frequently asked questions about the first day of school. What are you most worried about as you approach your first day as a teacher? In what areas are you most confident?

Maintaining and Regaining Your Sanity, One Month at a Time:

Chapter four charts the morale of teachers at different points in the school year. Why do you think you find teacher morale tends to follow this pattern?

Piles and Files: Organization and Time Management

In this chapter the author talks about her own struggles with organization, and shares the filing systems she eventually developed to deal with the inflow of paperwork. What are your own plans for keeping your classroom organized?

Your Teacher Personality: Faking it. Making it.

This chapter suggests building a teacher personality that rests on personal strengths and works around weaknesses. What do you believe will be your greatest strengths as a teacher? In which areas do you think you will need the most work? In what ways can you use your personal strengths to work around weak areas?

Classroom Management: Easier Said Than Done.

In this chapter, the author details potential pitfalls in management principles like consistency and positive reinforcement. Have you had any experiences in which “common sense” wisdom fell short? How did you deal with these situations and what did you learn from them?

Procedures that (Probably) Prevent Problems:

Chapter eight suggests that readers “beg, borrow, and steal” classroom procedures from other teachers, “… then adapt” those procedures to their own classroom. What procedures have you observed in the classrooms of other teachers that might work in your own classroom? What details will you change to make the ideas work considering your personality, age group, and subject area?

The Due Date Blues: When High Expectations Meet Low Motivation

Here the author talks about the heartache of watching students miss major assignments. Who is most responsible for making sure students turn in their work? How can we best promote responsibility in our students?

No Child Left… Yeah, Yeah, You Know

In chapter 10, the author discusses difficulties with individual students. She also says that many teachers have a specific type of student in mind when they choose their career, and are sometimes more effective with their favorite type of student. Which students do you think will be easiest for you to connect with? Which might be the most difficult?

Parents: The Other Responsible Adult

Chapter eleven includes many stories involving difficult parents, but the tone of the last two stories is different. Why do you think these stories were included? How would you deal with some of the situations discussed in the chapter?

The Teachers’ Lounge: Making it Work with the People You Work With

Chapter eleven describes difficult types of coworkers, including those who are overly negative, but also those who are positive to the point of bragging. Is there such thing as too much positivity? What do you believe is the proper balance between positive and negative when teachers talk about work?

Please Report to the Principal’s Office

Chapter thirteen discusses actions by administrators that make teachers’ jobs harder. How can teachers work with or around administrators who do these things?

Stressin’ About Lessons

In chapter 14 the author discusses reasons that seemingly well-planned lessons go wrong. How would you reign in a lesson that is starting to go off track? What back-up activities could you use if left with extra class time after a lesson?

Observation Information

In this chapter, the author addresses two schools of thought about dealing with observations: “Always teach like you are going to be observed,” and “the dog and pony show.” What are some potential pitfalls of each of these ways of thinking?

Testing, Testing

Chapter 16 deals with unintended consequences of testing. Is there a way to minimize these consequences while still holding teachers accountable for good teaching?

Grading Work Without Hating Work

Which of the grading tips in this chapter were helpful? What other strategies do you plan to use to keep up with grading?

Moments We’re Not Proud Of

In chapter eighteen, teachers share their low-points. Which of these stories did you find most memorable? Why?

Dos and Don’ts for Helping New Teachers In Your School

In this chapter, the author comes down hard on teachers who say things like, “That would never happen in my class.” In your opinion, what are the qualities of a good mentor? As you seek out informal mentors at your schools, what type of person do you hope to find?

Making Next Year Better

The author ends the book by saying you probably won’t be satisfied with the ending. Were you? Why or why not? How do you think you might have reacted differently to this book if you read it after, rather than before, your first year as a teacher?

Teacher Book Club Questions for See Me After Class

Teacher Book Club Questions for

See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers

by Roxanna Elden

General Questions

-The author mentions teacher movies several times in her book. In what ways does she seem think these movies are helpful to real-life teachers? In what ways does she suggest they hurt? Do you agree?

-Which chapter did you find the most helpful? Why?

-On page 111, the author lists “Ten Principles of Successful Living We All Hope Students Learn From Us.” Is there anything you would add to this list? What steps do you take in your classroom to integrate these principles into your subject matter?

Chapter-by-chapter questions:

In the first chapter of the book, the author addresses the three types of books on the market for new teachers: Professional development, inspirational stories, and general guidebooks. What does she say are the weaknesses of each type of book? Do you agree?

Which of the suggestions in the “Ten Things You Will Wish Someone Had Told You” chapter had you heard before you started teaching? Which lessons did you have to learn on the job?

In chapter 3, “First Daze,” the author lists and answers frequently asked questions about the first day of school. What were you most worried about as you approached your first day as a teacher? Were you worried about the right things?

Chapter 4 is charts the morale of teachers at different points in the school year. Do you find that your own morale tends to follow this pattern? Explain.

In chapter 5, “Piles and Files,” the author talks about her own struggles with organization, and shares the filing systems she eventually developed to deal with the inflow of paperwork. How important is organization in this profession? Can a disorganized person still be an effective teacher?

Chapter 6 suggests building a teacher personality that rests on personal strengths, and works around weaknesses. What are your greatest strengths as a teacher? What is your biggest weakness? In what ways do you use your strengths to work around this weakness?

Chapter 7 is called “Classroom Management: Easier Said Than Done.” It details potential pitfalls in management principles like consistency and positive reinforcement. Have you had any experiences in which common management wisdom fell short? How did you deal with these situations and what did you learn from them?

Chapter 8 suggests that readers “beg, borrow, and steal” classroom procedures from other teachers, “… then adapt” those procedures to their own classroom. Why is this last step so necessary? Have you ever tailored another teacher’s ideas to fit your own classroom? What details did you need to change to make the ideas work?

In chapter 9, “The Due Date Blues,” the author talks about the heartache of watching students miss major assignments. Who is most responsible for making sure students turn in their work? How can we best promote responsibility in our students?

In chapter 10, the author discusses difficulties with individual students. She also says that many teachers have a specific type of student in mind when they choose their career, and are sometimes more effective with their favorite type of student. Which students are easiest for you to connect with? Which are the most difficult?

Chapter 11 includes many stories involving difficult parents, but the tone of the last two stories is different. Why do you think these stories were included?

Chapter 12 describes difficult types of coworkers, including those who are overly negative, but also those who are positive to the point of bragging. What is the proper balance between positive and negative when teachers talk about work?

Chapter 13 discusses actions by administrators that make teachers’ jobs harder. Is it possible to work with or around administrators who do some of these things? How?

In chapter 14 the author discusses reasons that seemingly well-planned lessons go wrong. Has this ever happened to you? How did you handle it? What activities would you suggest to a new teacher left with extra class time after a lesson?

In chapter 15, “Observation Information,” the author addresses two schools of thought about dealing with observations: “Always teach like you are going to be observed,” and “the dog and pony show.” At your school, are you expected to stay ready for company, or prepare your best sample of teaching for scheduled observations?

Chapter 16 deals with unintended consequences of testing. Which of the consequences mentioned in this chapter have you experienced? Is there a way to minimize these consequences while still holding teachers accountable for good teaching?

Which of the grading tips in chapter 17 were helpful? What other strategies do you use to keep up with grading?

In chapter 18, teachers share their low-points. Which of these stories did you find most memorable? Why?

In the “Dos and Don’ts for Helping New Teachers” chapter, the author comes down hard on teachers who say things like, “That would never happen in my class.” Has anyone ever said this to you when you needed advice? Have you ever found yourself wanting to say this to someone else? Explain.

The author ends the book by saying you probably won’t be satisfied with the ending. Were you? Why or why not?

September 3, 2015

Sign Up for the New Teacher Disillusionment Phase Power-Pack Series

Note: The Disillusionment Power Pack is a one-month series of emails that will come every three days or so to get you through this month. It’s only for people who are having really bad days right now, so you have to sign up here to get it.

I probably wouldn’t have blogged during my first year of teaching. That year was defined by a constant sense that I was the weakest link, so I would never have had the courage to share my low points with the world.

I was too afraid that people would offer gently-phrased comments like, “You should try setting high expectations and creating a positive, data-driven, student centered learning environment where all children can learn. That’s what I do! All my students come to school excited to learn! Also, my students respect me. Maybe we can all discuss why you are the type of person that children don’t respect.”

Most of all, I was afraid that all of them would be right.

For better or for worse, there is no good way to “out” yourself as a bad teacher your first year. We hide behind expressions like “steep learning curve” that do not begin to capture what it feels like to feel like you are failing at the important job in the world.

If I were writing this my first year I would have ended up focusing on resume-like accomplishments, success stories, or at least taking great pains to show that no children were seriously harmed and I had learned an important lesson.

And yet, what I most needed during my first year was to hear from a future version of myself – someone who kept teaching in spite of these moments and became a great teacher – or at least a good teacher with moments of greatness. This was what eventually inspired me to write See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers, in which teachers from around the country share the lessons they learned the hard way.

But even in the book, most of the stories are anonymous.

The Disillusionment Power Pack is my small experiment in over-sharing for the first-year versions of myself. It includes records of my worst days as a new teacher, including pictures of journal pages from my first year so you know I’m not making anything up.

I don’t send these posts out to most of the people on my mailing list, nor is it one of the posts you’ll find when you scroll through my blog. It’s only for people who are having really, really bad days right now.

If that’s you, you can sign up here to receive the Disillusionment Power Pack – a one-month series of emails that will come every three days or so to get you through this month. And, as you’ll see in the next email, that might be all you need.

(c) Roxanna Elden

I Probably Wouldn’t Have Blogged During My First Year Of Teaching.

Note: This is the first email in the Disillusionment Power Pack series – a one-month series of emails that will come every three days or so to get you through this month. It’s only for people who are having really bad days right now, so you have to sign up to get it.

I probably wouldn’t have blogged during my first year of teaching. That year was defined by a constant sense that I was the weakest link, so I would never have had the courage to share my low points with the world.

I would have been too afraid that people would offer gently-phrased suggestions for improvement, like, “Why don’t you try setting high expectations and creating a positive, data-driven, student centered learning environment where all children can learn regardless of their background. That’s what I do and all my students come to school excited to learn! Also, my students respect me. Maybe we can be thought partners and deep dive into the issue of why you are the type of person that children don’t respect.”

Most of all, I was afraid that all of them would be right.

For better or for worse, there is no good way to “out” yourself as a bad teacher your first year. We hide behind expressions like “steep learning curve” that do not begin to capture what it feels like to feel like you are failing at the important job in the world.

If I were writing this my first year I would have ended up focusing on resume-like accomplishments, success stories, or at least taking great pains to show that no children were seriously harmed and I had learned an important lesson.

What I most needed to hear from during my first year was a future version of myself – someone who kept teaching in spite of these moments and became a great teacher – or at least a good teacher with moments of greatness. This was what eventually inspired me to write See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers, in which teachers from around the country share the lessons they learned the hard way.

But even in the book, most of the stories are anonymous.

The Disillusionment Power Pack is my small experiment in over-sharing for the first-year versions of myself. It includes records of my worst days as a new teacher, including pictures of journal pages from my first year so you know I’m not making anything up.

I don’t send these posts out to most of the people on my mailing list, nor is it one of the posts you’ll find when you scroll through my blog. It’s only for people who are having really, really bad days right now.

If that’s you, you can sign up here to receive the Disillusionment Power Pack – a one-month series of emails that will come every three days or so to get you through this month. And, as you’ll see in the next email, that might be all you need.

(c) Roxanna Elden

September 2, 2015

Classroom Management: Easier Said Than Done (Chapter Excerpt for Email Subscribers)

-CHAPTER EXCERPT FOR EMAIL SUBSCRIBERS-

Classroom Management: Easier Said Than Done

Phase I: Trying to Do It by the Book

Classroom management is a series of straightforward rules tested by millions of teachers and proven to work: Clearly lay out rules and procedures in advance. Have a specific chain of consequences for misbehavior, and give positive reinforcement for following rules. Create a classroom culture in which students respect each other and want to learn. Of course, as any teacher can tell you, planning engaging lessons has a lot to do with this. Most important, be consistent.

Well, you knew all this. In fact, you spent a long time making a “star chart” with each child’s name on a star, and explaining, “We are all stars in this classroom!” You have already informed them they have the chance to become “shining stars,” or even “superstars” by behaving well. Unfortunately, they could also end up as “falling stars” if they don’t follow the rules, which are printed in positive language on a large poster at the front of the classroom.

To make sure your expectations were clear, you asked a volunteer to demonstrate sitting quietly and waiting his turn. “Very good!” you said.

Then, to be even clearer, you let a student act out what it means to be a “bad kid.” This kid did a perfect impression. He got out of his seat, insulted another student, and threw paper on the floor. He talked in what can only be described as an “outdoor voice.” He had the class laughing and was definitely enjoying the attention. The only problem is, now you can’t get him to stop and the class is still laughing. An hour later he has worked through your chain of clearly stated consequences like Pac-Man but still won’t raise his hand to talk. You have silently nicknamed him “Consequence King.” His best friend is showing all the signs of becoming “Consequence Prince.”

After lunch the clock moves much more slowly than your students do. Your classroom begins to remind you of a bar full of little drunk people: They want constant attention and often don’t realize how loud they are talking. They have short attention spans; rarely think of the consequences of their actions; and, as you will find out tomorrow, they don’t always remember what happened the day before.

At the end of the day, no one’s name has moved up to “shining star,” let alone “superstar.” This is because you spent the whole day trying to keep Consequence King and his two (now three) new followers from starting an open-participation-anonymous-fart-sound contest. To make matters worse, your memory of the chaos includes a flurry of desperation moves that can only be described as inconsistent: You threatened to call everyone’s parents. You yelled at only one student when at least five were talking. You might have mentioned something about a pizza party. Panic slices through your exhaustion.

You describe the situation to another teacher, whose relaxed attitude shows that her day did not include any of these problems.

“Oh, sweetie, it’s easy. What you should have done is clearly lay out your rules and consequences, give positive reinforcement, make sure your lesson plans are . . .” You stop listening for a minute here because you just realized how much your feet hurt. Anyway, you know what she’s going to end with, don’t you? “. . . Above all, be consistent.”

Well-Known Classroom Management Advice: How to Make It Happen

If advice and intentions were enough, we would all floss regularly, call our grandmothers as often as we should, and get our oil changed every six months or 3,000 miles. We would keep our New Year’s resolutions, and we would certainly follow the classroom management principles we learned in training. Unfortunately, most management sound bites are easier said than done. Some setbacks are due to outside circumstances. Others are caused by our own inexperience. Either way, we don’t need to hear the same advice repeated. We’re looking for an answer to our real questions: “Why isn’t this working?” and “How can I make it work?”

Advice: “Be Consistent.”

Why It Helps

Kids have super-sharp “fairness” radar. Threats and promises work best when they are backed up by action and when rules apply to everyone.

The “good kids” want to see you know who’s causing the problem. That’s because it isn’t them.

The “bad kids” need to see someone else get the punishment they got yesterday. That way they know you weren’t just picking on them.

Some kids will test rules more than once. Repeat offenders need extra proof that you mean business.

Why It’s Easier Said Than Done

Students don’t have consistent needs. One student sometimes takes as much of your attention as the rest of the class put together, and you might have more than one of these students in a class. You may have students with behavioral disorders who have trouble controlling themselves. It’s hard to know if you should hold them to the same standard.

Students don’t have consistent behavior. Some kids are so much better behaved than others that you want to let them slide on the first offense. At the same time, you don’t want to seem like you are favoring anyone. Sometimes you’re tempted to come down on a good kid to show the troublemakers it’s not just them. There are also kids who get on your nerves. You may blame them for problems too often or overcompensate by ignoring their bad behavior.

Let’s be honest—sometimes you don’t feel so consistent yourself. It’s hard to be fair when you are tired and a million things are happening at once. You can’t respond to everything you see, and you don’t see everything that happens.

How to Make It Easier to Do

Promise less. When possible, don’t promise or threaten to call home—just do it. If you can’t get to it that night or the number doesn’t work, at least you kept your mouth shut and didn’t lose credibility.

Look the other way. If an offense is not serious and you can’t deal with it right away, pretend you didn’t see it. If the kids think you didn’t notice, you’re not being inconsistent. They’ll just think someone got away with something.

Follow through—reasonably. Instead of telling students you will do something every week or by a certain day, do things as often or as soon as you can. This includes things like changing seats or updating in-class progress reports. The more you follow a routine, the more you will get your students into a routine, but if you avoid promising routines you can’t keep up with, kids are more likely to buy into your next idea.

Turn follow-up plans into classroom jobs. Kids enjoy being helpful, and an enthusiastic student can run some systems better than an overwhelmed teacher. Whenever possible, let students update charts and files and remember everyday tasks. You can even give certain jobs as rewards.

Get as much sleep as possible. Well-rested people are more alert and better prepared to react to surprises. They are also less likely to overreact to small frustrations (a.k.a. children).

When in doubt, be too strict.

++++

The rest of this section addresses other common classroom management advice, including:

-Establish clear rules and consequences.

-Give positive reinforcement

-Plan engaging lessons

-Build a supportive classroom culture.

What do all these tips have in common? They are all solid advice that teachers learn in training. The problem is that – like a lot of good advice – they are easier said than done. Sure, we’ve posted our rules and consequences on the wall, they’re phrased in positive language, and we have every intention of enforcing them consistently. But then the students come in and present us with a non-stop series of judgment calls. At that point we’re not wondering whether it’s important to be consistent. We’re wondering whether that student who threw the paper ball was really aiming for the trashcan.

This doesn’t mean the original advice is wrong, though. That’s why the classroom management advice in the first section of this chapter divided into three segments:

-Why the basic recommendations usually work.

-Why they’re sometimes easier said than done.

-How to troubleshoot when things fall apart.

That’s section 1.

Section 2 offers ideas for rewards and consequences when the ones you’ve been using don’t seem to be working.

Section 3 talks about what no one wants to talk about – how to take charge of a class that is completely out of control. And it includes plenty of stories from teachers who have been there.

Your classroom door might closed, but when it comes to learning lessons the hard way as a teacher, you’re never alone.

© Roxanna Elden

+++++

To receive additional tips, updates, and resources about twice a month, Click here to join the email list.

August 19, 2015

Three Answers to the Question, “So, How Do I Get Published?”

At the end of my creative writing workshops, sometimes with only fifteen minutes left of the final class, someone inevitably asks, “So, how do we get our work published?” People also ask this question when they find out that I am the big-time smedium-time author of the breakaway, international bestseller moderately successful book See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers. Depending on the situation, I give one of three answers to this question:

If I’m feeling world-weary and sarcastic and/or it doesn’t seem like the person really wants a real answer anyway: Prepare for lots of rejection.

Note: For best results, I follow this with a sad-little laugh and well-timed sigh.

If the question is from a genuine hopeful author, but time is short and/or the person seems to want a short answer: My favorite book on this subject is The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published, by Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry. The authors are a wife/husband, agent/author team and the book is readable and funny and will save you lots of trial and error.

Note: The way potential authors react to this type of tip is telling. If they say thanks and make a note of the book’s title, that’s a pretty good sign. If they read the book – or, really, any book – on the publishing process, and then follow up with a few specific questions, that’s a great sign. If they say they are too busy to read a whole book, that’s a bad sign for their future as an author. It’s also a sign that they are going to want to explain to me how easy it’s going to be for them to write their book once they get started because their life is so interesting people keep telling them they should write a book! Then they are going to ask me how much I got paid for my book. Then they are going to ask if I can introduce them to whoever published my book so those people can publish their book. Then… I don’t know what comes next, because I have already made an excuse to leave the conversation, probably using my cool, world-weary “prepare for lots of rejection” line.

If the question is genuine AND there is enough time to explain the basics of the publishing process:

There are a few main steps to getting a book published.

If you’re working on a novel, you have to write the novel and make it as good as it can be. Then you write a query – which is usually a one-page email, to try to find an agent who will sell your work to publishers. If the agent is interested in the query, they will ask for all or part of your manuscript. If they like those enough, they will sign you up as one of their authors. You don’t pay the agent – they get a percentage, usually . Once you sign up with an agent, the agent will submit your work to editors at a publishing house. Then, hopefully, the publishers will buy your book and pay you an advance, then work with you to make the manuscript as good as it can be, then publish it and make it into a book. In almost every case, you’ll be have to do most of the work to get people interested in buying the book. If the book sells enough copies to earn back your advance, you’ll start getting royalties, which usually come out to about a dollar per book sold.

If you’re working on a non-fiction book, almost everything is the same as above, except you don’t have to write the whole book. You have to write a proposal, which includes three chapters and some other things, such as a description of your competition and expected audience and a bio that explains why you’re the right person to write this book and why you think you can sell it. Then you send queries to agents. If they like the query, they will ask for the proposal instead of the completed manuscript. If they like that, they may be able to sign you and even sell your book based on the proposal. But in the mean time, keep working on your book.

For details and additional information, my favorite book on this subject is The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published, by Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry. The authors are a wife/husband, agent/author team and the book is readable and funny and will save you lots of trial and error. The book is a comprehensive guide through every step of the publishing process. You can use it as a reference book or read it straight through, and it will save you lots of trial and error. It’s especially good for non-fiction because the authors include their own book proposal in its entirety and you can use it as a model. For fiction authors, I also really like the book The Art of War for Writers, by James Scott Bell. Bell’s book is organized into readable, bathroom-read-length chapters that provide a mix of encouragement, writing advice, and publishing advice. For guidance on the writing process, I’m not alone in recommending Stephen King’s On Writing, which is half memoir, half solid advice for writers. And if you need a pick-me-up in the face of inevitable rejection, check out Catherine Wald’s collection, The Resilient Writer, which is an anthology of rejection stories from 23 now-successful authors.

While all of the books mentioned above are worth reading, you’ll also find quite a bit of overlap in the advice they offer. That’s because the overarching advice authors need to hear is actually simple; we just need to hear it from a lot of different sources because writing a book is a long process.

Here is my distillation of the writing advice I’ve found in all these books and from my own experience. Learn as much as you can about the publishing process and industry. Set aside time to get your book written and get it on paper at the quickest, steadiest pace as you possibly can. Get feedback from sources you trust, and expect to do lots and lots of revisions. If you need a number, expect to do about 30 revisions. Some revisions will consist of small edits because you’re sure you’re almost done. Others will be complete overhauls of the organization and story after you realize you’ve been doing the whole thing wrong. Then, send the most professional materials you can create to the best fitting agents you can find.

And prepare for lots of rejection.

(c) Roxanna Elden

To receive additional tips, updates, and exclusive materials about twice a month, Click here to join the writer, teacher, or parent email lists.

Or, click here to sign up yourself or a friend for a four-week, humor writing mini-course.

Self-Editing Tips for Writers

These self-editing tips are based collectively on submissions from my adult creative writing workshops. They are tips meant for advanced rather than beginning writers, though they apply to almost every writer. They are generally more helpful in editing a first draft into a second draft, so don’t feel like you need to keep them in mind as you are writing. Get your writing onto the paper first. That’s the most important part. Then pick ONE of the following tips and edit for that.

Sentence structure variety: The more, the better. You want long, short, and medium sentences in every paragraph. (For my grammar snobs and English teachers: you want simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences in every paragraph.) Try to avoid two sentences with a similar rhythm right next to one another, unless it’s really on purpose. For example, you don’t want a whole bunch of sentences clumped together that have a comma followed by “and.”

Beware of your “pet” word or phrase. Most writers have a few things they say way too much in their writing. (Mine are “suddenly,” “of course,” and “it seemed.” You probably know yours. If you don’t, you can ask a reader to try to figure it out.) Do a word search for these phrases and replace them wherever possible.

Watch the clichés: If an image, description, or metaphor rings a bell, there’s a pretty good chance it’s a cliché. It can be surprisingly hard to think outside the box enough to find the clichés in your own writing, so ask a trusted friend to go through your work with a fine-toothed comb and see what catches their eye.

Stephen King’s advice on adjectives and adverbs: Get rid of them whenever possible. It’s good advice. It forces you to make the nouns and verbs do the heavy lifting, meaning-wise. For example, if you’re saying “ran quickly,” why not just say “sprinted?” Then again, you can also just say “ran,” because the “quickly” part is implied. If you are an adjective- or adverb-addict, try saving a draft of your work, then making a copy and trying to remove every single adjective and adverb from the copy. If there are a few lingering adjectives or pesky adverbs you just simply can’t part with, those are most likely the ones you really, genuinely need- or you’re just being an editing wimp.

Parenthesis: In the end, you almost never need them. They are often a sign of information that you thought of while writing that you wish you’d included earlier in the piece (so if you find that they pop up in a lot of your early drafts, that’s okay). On the second draft, try to find a better home for the information you initially placed in parenthesis.

(c) Roxanna Elden

+++++

Click here to sign up yourself or a friend for the four-week, humor writing mini-course.

To receive additional tips, updates, and exclusive materials about twice a month, Click here to join the writer, teacher, or parent email lists.

August 16, 2015

Using the Tools of Standup Comedy to Make Your Writing Funnier (Humor Writing Mini-Course, Class 3)

Welcome to the third class in your 4-week, humor writing mini-course. This lesson talks about some basic principles of writing jokes for standup comedy and how these might apply to your writing.

Here is a very condensed summary of how standup comics write jokes:

There are three parts of a joke: The premise, the setup, and the punch.

Sometimes there is also a tag, which is an additional punch line without a new setup.

Premise = topic + feeling about topic + reason for feeling (in any order): “I hate parking for this class because there’s always a line,” or, “You know why I hate parking for this class? There’s always a huge line,” or, “I love coming to class. I just wish the parking line was shorter.”

Setup = Leads from the premise to the punch line, and provides the information needed to understand the punch line. “All the way here, I was so happy I avoided traffic, then…” or “There was actually a cop directing traffic. I said, ‘what happened, is there some type of big event going on?”

Punch: The funny part. This is where the audience should laugh. “Then I get here and the entrance to the parking lot is like a… parking lot,” or, “The cop says, ‘yeah. English 101.’”

Note: These jokes are bad, but that’s okay. Even the best comics write tons of jokes before they get a good one.

+++++

Want to know more about how to write jokes for standup comedy – or even just how to be funnier when you speak? Check out these books:

Zen and the Art of Standup Comedy, Jay Sankey – A book that talks about all the delicate balances a speaker has to strike when trying to make an audience laugh. I’ve also found this one helpful as a teacher.

Step-by-Step to Standup, Greg Dean – A book that breaks down joke structure to help with joke writing.

+++++

Here are some joke-writing tips from standup comedy that might also apply to your writing.

-Use words with hard sounds: Letters like K, T, and P are funnier than letters like S, L, and M. All other things being equal, saying, “I got sick from the chicken,” is funnier than saying, “I was ill from the fish.” I don’t know why this is, but it works.

-Say it happened to you. Pretend the story happened to you or someone close to you, even if it didn’t. Kevin Hart saying he got chased by an ostrich is funnier than Kevin Hart saying his friend’s cousin’s ex-girlfriend got chased by an ostrich.

-Say it happened recently. If you are telling a story that could have happened this morning, say it happened this morning.

-End with the word or image that will make people laugh. If you keep talking, the audience will stop laughing to hear you – also called “stepping on” your laughs.

-Keep the setup as short as possible. Get to the laugh as fast as possible. Eliminate extra words in your setup.

-Exaggerate – but not too much. Gabriel Iglesias saying he ate 11 cakes is funnier than if he said one cake… but also funnier than if he said he ate 300 cakes.

-Tell jokes that fit your character. When you are onstage, you are a character similar to yourself. If your joke makes you sound like an insensitive jerk, your character on stage must be an insensitive jerk. If your joke makes you sound like you take things too seriously, your character should get mad easily.

Today’s Assignment

Pick an inside joke or a “you had to be there” moment and describe it for your readers in enough detail that they get it. Use the tips above to bring readers inside your “inside joke.”

+++++

Click here to navigate back to the class overview, which contains links to all lessons.

+++++

The humor writing mini-course is a free, four-week email series. If you’re not enrolled in the class and want to start these lessons from the beginning, click here to sign up.

(Note: I don’t like to overload any of my lists with unwanted emails, so even if you are signed up for one of my main email lists, you will need to click the link above to sign up for the course.)

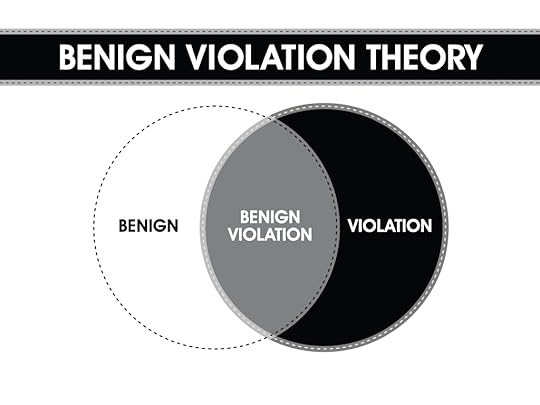

Using “Benign Violation Theory” to Make Your Writing Funnier (Humor Writing Mini-Course, Class 2)

Welcome to class two of your 4-week, humor writing mini-course. In this lesson we’ll talk about how to choose the right level of detail to make your writing fit into the “Benign Violation” Theory of humor. (And if that’s not a hilarious class description, I don’t know what is.)

How to use “Benign Violation” Theory to Make Your Writing Funnier

Remember Peter McGraw’s “Benign Violation Theory” from lesson one? (Here’s the link if you missed it.)

(You can also read about it in more detail in McGraw’s book, The Humor Code.)

Here’s a quick recap of the theory as it relates to today’s lesson:

To be funny, something has to be a “violation”… That means it has to go against what we expect and/or feel is appropriate. If your joke is not enough of a violation, you’ll probably find yourself getting a sympathetic nod instead of a laugh.

…but it also has to be benign. That means it’s safe enough not to hurt. If your joke is not benign enough, you’re likely to find yourself on the defensive, complaining that your Facebook friends take everything too seriously and that people need to chill out. Or having to fall back on the cliche classic followup line for a not-benign-enough joke: “Too soon?”

Microscope vs. Telescope

Today’s exercise is designed to help your writing fall into the sweet spot on the Venn Diagram below. The first thing to do is think about your subject matter (or your current draft) and decide where it falls on the diagram. Then decide whether you need to take the “microscope” approach or the “telescope” approach to make it funny.

The “Microscope” Approach

If the subject matter is small and frivolous and unemotional, it naturally falls into the benign category. You can use a “microscope” approach by bring it closer to your readers and violate their expectations. (Comics and writers who do this well include Kevin Hart, Jerry Seinfeld, Woody Allen, John Mulaney, Steve Almond, and Roz Chast)

Steve Almond in Against Football

(Describing his favorite team, the Oakland Raiders)

“For those who are not familiar with the Raiders, they are the epitome of the term once proud, a franchise incapable of accepting that its best years are past. I think of them as the NFL’s version of a wildly popular child actor who starred in a couple of minor hits in the eighties and has now grown into an ugly, entitled, coke-addicted adult who struts around D-list parties in mirrored sunglasses and parachute pants reeking of Polo cologne and insulting women who decline his invitation to head back to his pad to check out his python. There is a chance I have given this analogy too much thought.”

This violates our expectations because analogies are usually short and simple. Think about some of the analogies that have become cliches: Shooting yourself in the foot. Biting the hand that feeds you. The shorter the image, the more quickly we’re able to grasp the comparison. We could have understood the childhood star analogy in just a couple of words, but the longer the description goes on, the funnier it gets.

Roz Chast

Another great example is this “Cozy Cardigan” cartoon by Roz Chast.

(In hhe narrator is someone who is supposed to be writing catalogue copy for a sweater. Readers expect very little personality and emotion to come through in this type of writing, but as you can see in the cartoon, that’s not the case for this narrator.

Tips for putting your subject under a “microscope”

-Overdo the details to the point that it becomes an inappropriate level of detail, as Steve Almond does in the example above.

-Exaggerate the emotional impact felt by the person involved so it becomes an inappropriate reaction, as in the Roz Chast cartoon.

-Tell the story through the eyes of a child. (David Sedaris does this well.)

-Act as if the story just happened. (i.e. A traffic-related story might be interesting or funny the day it happened. If you’re still telling the same story of getting cut off by some jerk eating a muffin ten months later, it’s not as funny.)

The “Telescope” Approach

If your subject matter is something very serious or sad, it’s already on the violation side of the spectrum. To make it funnier, you need to lighten it up a bit by giving readers some distance. (Comics and writers who do this well include Sarah Silverman, Anjelah Johnson, Mishna Wolff)

Paraphrased example from standup comic Anjelah Johnson:

“My mom had four kids… my dad had five… so, that’s what happened there.”

Tips for using the “telescope” approach to give readers distance from a subject:

-Deliberately withhold details

-Minimize the emotional impact

-Show that a lot of time has passed

-Show that it turned out okay for the person in the end (AKA – your painful childhood bullying experience is funnier if you are a now successful comic or a millionaire author like David Sedaris)

-Showing that the person learned the lesson and is better for the experience

-Make the narrator unsympathetic, even if the narrator is you

Today’s Writing Assignment

Write something based on the prompt below. As you write, think about where you can use the “microscope” approach to bring something closer to readers or the “telescope” approach to add distance between the readers and the subject matter.

Prompt: Write a piece that starts with the words, “I don’t know why I still remember this…” Then, describe the memory in as much detail as possible, hopefully until the reason you do remember this random thing becomes clear.

+++++

Click here to navigate back to the class overview, which contains links to all lessons.

+++++

The humor writing mini-course is a free, four-week email series. If you’re not enrolled in the class and want to start these lessons from the beginning, click here to sign up.

(Note: I don’t like to overload any of my lists with unwanted emails, so even if you are signed up for one of my main email lists, you will need to click the link above to sign up for the course.)