Roxanna Elden's Blog, page 16

October 6, 2015

The Three Layers of Complex Characters

Note: This is an online version of a writing workshop currently in progress: Learning, Then Burning (Or at Least Overturning) the Writing Rule Book. You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

The Three Layers of a Complex Character

Top Layer – Potentially Protective

This layer is socially acceptable but superficial – and often somewhat transparent. Characters (and real people) hold onto it to the degree they (and we) need to, some more tightly than others. But it’s usually at least somewhat obvious that there is something underneath. For example – a character may constantly wear brand name clothes and talk about taking expensive vacations, but there is a sense they are hiding some insecurity.

Middle Layer – Potentially Defective

The second layer consists of traits a character is trying to conceal with the top layer. They are usually less socially acceptable, and often less noble than the top layer. For the character above, this layer would be the layer that is a gold digger or social climber who uses people in their efforts to seem wealthy.

Inner layer – Undeniably Human

Underneath the other two layers, however, is a human core. Characters (and people) bury this level deeply, because rejection at this level really hurts. But it’s this human core that is the most universal. If we can see the human core of a character, we will understand and care for them. If a character can find and learn to accept their own human core, they will acheive inner peace to the degree it’s possible. For the character above, this means we learn why he or she is so afraid of seeming poor. Maybe they grew up in a situation where their needs weren’t met or they were bullied for being the badly dressed kid at school. Maybe they are desperate for their own kids not to have the same experience. No, don’t you feel like a big ol’ meanie for jumping to conclusions?

Writing Assignment:

Take a character you want to write about. Perhaps the one you sketched out in the first part of this lesson.

Write a character sketch that addresses each of these three levels.

Writing tip:

Each of these levels can be widened or narrowed to make a character more or less sympathetic. Want to make us care for your character? Show us a lot of that human core. Want to keep them unlikeable? Focus on the defective layer and its superficial coverup.

+++++

This is an online version of a writing workshop by Roxanna Elden, author of See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers. (And hopefully some other books, soon.)

You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

Writers – Do Your Characters Have to be Likeable?

Note: This is an online version of a writing workshop currently in progress: Learning, Then Burning (Or at Least Overturning) the Writing Rule Book. You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

Do your characters have to be “likeable?” Based on our in-class discussion, the answer is a resounding no. Here are some of the characters in books, movies, and TV shoes that we don’t like… but still manage to love.

Dr. House from House

Professor Snape from Harry Potter

Hatsumomo from Memoirs of a Geisha

Agent Smith in The Matrix

Meryl Streep’s character in August: Osage County

Meryl Streep’s character in The Devil Wears Prada.

Jake Gillenhaal’s character in Nightcrawler

Thieren from Game of Thrones

Reese Witherspoon’s character in Wild

The writer in Californication

The commentator of Hunger Games

Walter White from Breaking Bad

Frank Underwood from House of Cards

The main character’s brother in Slumdog Millionaire

We could go on…

But a closer look at even the list above reveals some patterns. The characters we don’t like often fit in one or more of the following categories.

We don’t like the character, but…

… we respect them for their special skill set or outlook on life. (Thieren from Game of Thrones, Dr. House from House)

… we feel sympathetic to them because their outer unpleasantness reveals a certain amount of inner pain. (Meryl Streep’s character in August: Osage County, the writer in Californication, Hatsumomo from Memoirs of a Geisha)

… we’ve developed a bond with them because we first met them before they went over to the dark side. (Walter White from Breaking Bad, Jake Gylenhaal’s character in Nightcrawler)

…there is something redeemable about them that we hope will overtake their evil side. If they undergo a redemption, it will give us hope that people can change. (Reese Witherspoon’s character in Wild, the main character’s brother in Slumdog Millionaire.)

…we like the author for nailing down personality traits in a way that feels real. (This is personal, so take your pick from any of the above.)

TVTropes for unlikeable characters: There are a ton of variations of each of these, but these will give you an idea of how people in the movie/TV world describe these traits.

–Pet the Dog Moment (Interestingly enough, Frank Underwood kills a dog in the first scene of HOC – perhaps a nod to this trope.)

–Not evil, just misunderstood

–Heel-face-turn, in which a bad character turns good, or face-heel-turn, in which a good character turns bad.

Reading Assignment

The excerpt we used for this lesson is from I Am Charlotte Simmons, by Tom Wolfe.

This is a campus novel in which different characters are our tour guides through different chapters, but some characters are more sympathetic than others. This chapter, the first chapter after a quick opening description, is called “The Dupont Man.” It’s third person, but follows the point of view of Hoyt, a fraternity member who we first meet in the bathroom of a frat party.

Click here to see the book and read the excerpt through Amazon’s “look inside” feature.

Writing Assignment #1: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Premise: Often, bad traits have a positive flip-side. Often, good traits have a negative flip-side that is negative. Think of the reasons people break up – they were attracted to someone’s ambition only to find out the person works all the time. Or they liked someone’s laid back attitude only to find out they are frustratingly lazy or don’t follow through on their promises. The same is true for character traits. The things that bother us about an unlikeable character can be the thing we would like about them if it were less extreme or better controlled, and the thing that makes us like a character can get on our nerves if it becomes extreme.

Directions:

1. List five character traits that you like in a person, along with their potential downsides. Remember that the downside is often a more extreme version of the upside.

(Examples: Generous / bad With Money; Sweet / Pushover)

2. Then list five character traits you don’t like in people along with their potential upsides. Remember that the upside is often the better-controlled, less extreme version of the downside.

(Examples: Jealous / Attentive; Violent / Brave or protective of loved ones)

3. Now, pick one set of characteristics from each list and write a character sketch of someone who embodies both the positive and negative trait. Tell us everything you can describe about this character that might be relevant to the story. They don’t actually have to do anything yet. A character sketch is just a description.

Note: This exercise can be great for those Dr. House type characters that we don’t like but do respect. It can also help you make your heroes more flawed and thus more human and relatable. After all, likeable doesn’t mean perfect.

Want to take your characters to the next level?

Or, a better question might be, want to dig down to the next layer?

Click here for Writing Exercise #2: The Three Layers of Complicated Characters.

+++++

This is an online version of a writing workshop by Roxanna Elden, author of See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers. (And hopefully some other books, soon.)

You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

September 28, 2015

Announcing the New Teacher Disillusionment Power Pack (A Free Resource)

Note: The Disillusionment Power Pack is a one-month series of emails to help teachers get through the hardest part of their first year. The content of these emails does not go out to any of my other mailing lists and is not available on this blog.

In fact, I probably wouldn’t have blogged during my first year of teaching. That year was defined by a constant sense that I was the weakest link, so I would never have had the courage to share my low points with the world.

I didn’t even speak up in meetings with other new teachers. I was too afraid that people would offer gently-phrased comments like, “Why don’t your try setting high expectations? Or creating a positive, data-driven, student centered learning environment where all children can learn! That’s what I do, and all my students come to school excited to learn! Also, my students respect me. Maybe we should discuss why you are the type of person that children don’t respect.”

Most of all, I was afraid they would be right.

For better or for worse, there is no good way to “out” yourself as a struggling teacher your first year. We hide behind expressions like “steep learning curve” that do not begin to capture what it feels like to feel like you are failing at the most important job in the world.

If I were writing this my first year I would have ended up focusing on whatever resume-like accomplishments or success stories I could muster. Even if I had shared a mistake or two, I’d take great pains to show that no children were seriously harmed and I had learned an important lesson.

And yet, what I most needed during my first year was to hear from someone who would be brutally honest about how tough teaching truly is. Especially when you feel like the weak link. Especially when everyone around you is sharing success stories, or resume-like accomplishments, or minor mistakes in which no children were seriously harmed. I needed to hear from someone who’d wondered, like I often did, if their students would have been better off with a different adult in front of the classroom. I needed to hear from someone who kept teaching in spite of these low points and became a successful teacher.

In other words, I needed to hear from a future version of myself.

This was what eventually inspired me to write See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers, in which teachers from around the country share the lessons they learned the hard way.

But even in the book, most of the stories are anonymous.

The Disillusionment Power Pack is the series of emails I’d send to the first-year-teacher version of myself. It includes records of my worst days as a new teacher, including pictures of actual journal pages and the stories behind the stories I now tell in speeches and public writing.

I don’t send these emails out to most of the people on my mailing list, nor are they part of the material available on this blog. They are only for people who are having really, really bad days right now.

If that’s you, you can sign up here to receive the Disillusionment Power Pack – a one-month series of emails that will come every few days to get you through one tough month of teaching. And, as you’ll see in one of the first of those emails, one month might be all you really need.

(c) 2015 Roxanna Elden

Announcing the New Teacher Disillusionment Power Pack

Note: The Disillusionment Power Pack is a one-month series of emails to help teachers get through the hardest part of their first year. The content of these emails does not go out to my regular mailing lists and is not available on my blog.

I probably wouldn’t have blogged during my first year of teaching. That year was defined by a constant sense that I was the weakest link, so I would never have had the courage to share my low points with the world.

In fact, I didn’t even speak up in meetings with other new teachers. I was too afraid that people would offer gently-phrased comments like, “Why don’t your try setting high expectations? Or creating a positive, data-driven, student centered learning environment where all children can learn! That’s what I do, and all my students come to school excited to learn! Also, my students respect me. Maybe we should discuss why you are the type of person that children don’t respect.”

Most of all, I was afraid they would be right.

For better or for worse, there is no good way to “out” yourself as a struggling teacher your first year. We hide behind expressions like “steep learning curve” that do not begin to capture what it feels like to feel like you are failing at the important job in the world.

If I were writing this my first year I would have ended up focusing on whatever resume-like accomplishments or success stories I could muster. Even if I had shared a mistake or two, I’d take great pains to show that no children were seriously harmed and I had learned an important lesson.

And yet, what I most needed during my first year was to hear from someone who would be brutally honest about how tough teaching truly is. Especially when you feel like the weak link. Especially when everyone around you is sharing success stories, or resume-like accomplishments, or minor mistakes in which no children were seriously harmed. I needed to hear from someone who’d wondered, like I often did, if their students would have been better off with a different adult in front of the classroom, but who kept teaching and became great – or at least good with moments of greatness.

In other words, I needed to hear from a future version of myself. This was what eventually inspired me to write See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers, in which teachers from around the country share the lessons they learned the hard way.

But even in the book, most of the stories are anonymous.

The Disillusionment Power Pack is the series of emails I’d send to the first-year version of myself. It includes records of my worst days as a new teacher, including pictures of journal pages from my first year and the stories behind the stories I now tell in speeches and public writing.

I don’t send these posts out to most of the people on my mailing list, nor is it one of the posts you’ll find when you scroll through my blog. It’s only for people who are having really, really bad days right now.

If that’s you, you can sign up here to receive the Disillusionment Power Pack – a one-month series of emails that will come every three days or so to get you through this month. And, as we’ll discuss in one of the first of those emails, that might be all you need.

(c) 2015 Roxanna Elden

September 25, 2015

Do You Need an Original Plot to Be a Good Writer? The Seven Basic Plots Divided into Seven Sections Each

Note: This is an online version of a writing workshop currently in progress: Learning, Then Burning (Or at Least Overturning) the Writing Rule Book. You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

Does Your Plot Need to Be Original?

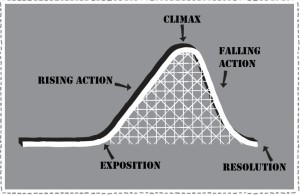

In the previous lesson, we described two different ways of looking at basic plot structure, and hopefully you did the fifteen-minute outline exercise at the bottom of the post.

One of the students in the in-person version of this class asked a very smart question: A plot structure is often described as having five parts. Does that mean each part has to be the same length? And, if not, how do we decide how long each of these parts are supposed to be?

Good question. To answer this, it can be more helpful to further divide your plot “roller coaster” into seven parts by separating the Rising Action into three different sections, each of which increases the pressure on the main character. After all, even on a real roller coaster, we spend most of our time on the slow climb to the top.

Now it’s time to take your outline to a slightly less basic level.

The Seven Basic Plots

Christopher Booker, in his book The Seven Basic Plots, explains that there are actually seven plots that most stories fit into. You can also read more about this on TVtropes, here. This is writing, so you’ll be able to find plenty of people who disagree or have their own take on this. To me, this was a revelation the first time I heard about it, and has guided my writing ever since.

Below you’ll find my quick summary of each of the seven basic plots, divided into seven sections each.

But before you start scrolling through these, here is your writing assignment: Find the plot that best fits your story.

Cut and paste it into a word document if you’d like a reference point.

Take your original, five-part outline and add whatever details are necessary to expand it to the seven-part version.

Note: You may find that your story falls in between two of these plot lines. For example, Cinderella and the movie Pretty Woman are both similar and have elements of both the Rags-to-Riches and Romantic Comedy plot lines. With that in mind, here is your… Optional second part of this assignment:

Figure out which plot is the second best fit for your story.

Cut and paste it into a word document for a reference point.

Fill out the parts that are different from your first outline.

See what interesting new details emerge.

Okay. Seriously. Here are the seven plots.

Rags to Riches

Exposition: We meet a young person who is poor and mistreated by others. This is the hero, but he or she doesn’t know it yet.

Rising Action Part 1: The hero gets some type of lucky break. Sometimes magic is involved, sometimes not. Either way, things seem to be looking up.

Rising Action Part 2: Everything suddenly goes wrong. The initial win is stripped away. The hero is separated from that which s/he values most. The hero is overwhelmed with despair and this seems to be the worst moment in the story.

Rising Action Part 3: The hero has lost the magic or good luck that helped during the first half of the story. Now it is all about wits and natural skills – no more easy outs. In the process, the hero shows independence and strength.

Climax: After the ordeals that show off the Hero’s newfound strength, the Hero must undergo a final test, one climactic battle against the Big Bad Something.

Falling Action: At last the hero emerges victorious

Resolution: The hero lays claim to the treasure, the kingdom, and the Prince/ princess, “… and they all lived happily ever after.”

Overcoming the Monster

Exposition: We meet a “monster,” bad guy, or bad situation that needs to be dealt with.

Rising Action Part 1: We meet a hero. He/She demonstrates some basic heroic qualities, but is otherwise minding his/her own business. The monster is on its way to mess with the hero, but for now, everything seems under control.

Rising Action Part 2: The Monster shows up and shows off, and seems to be overpowering the hero.

Rising Action Part 3: Time for the climactic battle. The odds seem to be against our Hero even surviving this fight. But, of course, we know how these things turn out, right?

Climax: The hero makes a thrilling escape from death, defeats the monster, or breaks the monster’s power.

Falling Action: The people who had been under its power are liberated. The Hero emerges victorious.

Resolution: The hero gets a treasure, a kingdom, and a princess (or prince). They all live happily ever after… unless you want to leave room for a sequel.

The Quest

Exposition: The hero finds himself in a situation where he must set out on a journey with a specific goal in mind. For whatever reason, ignoring the call and staying home is just not an option.

Rising Action Part 1: The hero heads out over hostile terrain (ocean, desert, middle school, etc.) and faces many obstacles (pirates, volcanoes, evil cheerleaders, etc.) along the way.

Rising Action Part 2: The hero meets up with some weird, creepy, or supernatural force. This meeting leaves the hero with some information that will help later in the journey.

Rising Action Part 3: The journey is over and the goal is in sight, but the story is not over. We reach the halfway mark, and the journey part is over. There is still a big obstacle to be overcome.

Climax: The hero must pass a final test. Passing the test will require the natural traits of the hero, but also the skills & knowledge gained during the journey.

Falling Action: The hero passes the test and accomplishes the goal.

Resolution: The Hero has won it all: treasure, kingdom, & Princess (or prince). Time to live happily ever after… unless the writer is leaving room for a sequel.

Voyage and Return

Exposition: We meet our hero – usually someone who is very innocent or feels trapped in everyday life. Somehow the hero ends up in some alternate reality or new world.

Rising Action Part 1: The new world is puzzling and unfamiliar and kind of cool. The hero will never really feel at home here, but that doesn’t seem to matter right now. The hero may meet someone who seems to be helpful.

Rising Action Part 2: The “mood of the adventure” starts to darken. The cool new world is starting not to be so cool, and the hero feels like she or he is in some type of danger. The previously helpful person may betray the hero.

Rising Action Part 3: The sense of danger gets worse. It looks like the hero is doomed!

Climax: The hero makes a dramatic or thrilling escape from the now-dangerous world.

Falling action: The hero returns to the world he/she came from.

Resolution: The hero has learned an important lesson from the adventure… or was it all just a dream.

Tragedy

Exposition: We meet a protagonist who has some type of flaw that will undo him later. The protagonist is focused on getting something – often something he or she has no right to have.

Rising Action Part 1: The protagonist seems to be getting away with his plan.

Rising Action Part 2: Things start to go wrong. The protagonist experiences difficulties and annoyances. He makes decisions that lock him into doing worse things in the future.

Rising Action Part 3: Things are now slipping seriously out of the protagonist’s control. He has a mounting sense of threat and despair. Forces of opposition and fate are closing in on him.

Climax: The protagonist is about to go down, hard. Mistakes and enemies made throughout the story have finally caught up to him/her.

Falling Action: The Tragic Hero’s death or destruction releases the world from the darkness s/he had wrought, and the world rejoices.

Resolution: The protagonist is gone and the world rebalances itself. Or we switch to a rebirth story of some sort.

Rebirth

Exposition: The hero falls under the shadow of a dark power. (Addiction, imprisonment, kidnapping, magic spells, illness, etc.)

Rising Action Part 1: The hero gets a ray of hope… maybe things are looking up.

Rising Action Part 2: The ray of hope disappears. Things seem even worse than before.

Rising Action Part 3: Things get even worse.

Climax: The dark power seems to have completely triumphed over the hero.

Falling action: The hero is saved at the last minute – either by his/her own efforts, a love interest, or an innocent character like a child.

Resolution: The hero has changed. You decide how.

Romantic comedy

Exposition: We meet a large cast of characters, including at least two people who are clearly meant to be together.

Rising Action Part 1: Some force is keeping the potential couple apart. Maybe they dislike one another, or one is in a relationship.

Rising Action Part 2: The force keeping the couple apart weakens and they start to get together.

Rising Action Part 3: Just when it seems like the couple will finally get together, a misunderstanding is created that seems it will keep them apart forever.

Climax: The misunderstanding is cleared up… but is it too late?

Falling Action: The couple finishes working out the misunderstanding and the relationship is back on track.

Resolution: Everyone lives happily ever after and everyone who is meant to be together ends up together.

September 24, 2015

Basic Story Structure, The Plot Roller Coaster, and Lauren Oliver’s “Story Algebra.”

Note: This is an online version of a writing workshop currently in progress: Learning, Then Burning (Or at Least Overturning) the Writing Rule Book. You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

Here is a basic explanation of plot structure – similar to what you’ll hear in any high school class.

Exposition

Establish character

Establish setting

Establish situation – what is the routine the main character is used to?

The exposition ends with an inciting incident that breaks up the routine and sets the main character on a quest. (Note from YA author Lauren Oliver: The inciting incident can be luck, but all other steps must be character’s own decisions.)

Rising Action

The plot thickens… the roller coaster climbs… pick your plot-related cliché.

This is the longest part of the story – there are usually at least three events or decisions, each of which raise the stakes higher.

All steps must be the character’s own decisions. Often, characters’ efforts to get out of trouble can get them deeper into trouble, turning the tension screws, and raising the stakes.

Climax

The emotional high point of the story.

(Lauren Oliver describes this as the utter failure and epic collapse of the original thing the main character wants…

Falling action

Things “fall” into place. Misunderstandings are cleared up. The real bad guy is revealed, found, and taken down. The real biological mother is revealed, found, and reunited.

As an author, you can think of this as a time to fulfill the promises you’ve made to readers, close all the doors you’ve opened, answer the questions you’ve raised in readers’ minds. (If a cat runs away early in the story and the main character searches for it, we should find out what happened to the cat.)

(According to Lauren Oliver… in the process of failing at what they want, the character will find out what they need.)

Resolution

Tie up any last loose ends. Let us know the main character’s new “normal.

End the story before the reader loses interest. This part is short.

You’ve also probably seen this diagram, which illustrates the five-part plot structure above:

Here is another way of looking at basic plot structure: “Structural Algebra”

(This is my favorite simple explanation of story structure. It’s from a Writers Institute class by YA author Lauren Oliver )

A page-turning story can be summarized like this:

_________ must ___________ before ____________ or else __________.

With blanks filled in, it’s:

(main character) must (goal) before (ticking time bomb) or (stakes).

Then, part 2:

Failing to do so, __________ discovers that in fact ________________.

With blanks filled in, it’s: Failing to do so, (main character) discovers that in fact (truth main character needed to realize).

Discussion / Mental practice exercise

Try to fit the plot of one (or more) of the following into both of the plot descriptions described above:

-The story of Cinderella (Why does it seem like every writing class uses Cinderella for this? Because it’s familiar and fits well.

-Your favorite movie.

-Your favorite children’s book. One good, cute example that fits well is Giraffes Can’t Dance, which we read in class.

Here is how Giraffes Can’t Dance fits into each of the examples above. (Warning: This summary contains spoilers. Don’t read on if you want to find out yourself whether Gerald the Giraffe learns to dance by the end of the story!)

Exposition:

Main character – Gerald the Giraffe

Setting – Jungle

Situation the main character is used to – being clumsy and awkward. Gerald can barely walk without tripping! He certainly can’t dance, right?

Inciting incident – The Jungle Dance. Gerald is going to have to leave his comfort zone of “standing still and munching shoots off trees.”

Rising Action:

All the other animals are great dancers. One by one we see that they each have a cool dance they can do at the Jungle Dance. Pretty soon it’s going to be Gerald’s turn. Uh oh!

Climax:

Gerald tries to dance but the lions “saw him coming and they soon began to roar.” Gerald gets laughed at, bullied, and called weird. Then, saddest of all, he has to walk home alone while all the other jungle animals do a conga line without him. So, so sad!

Falling action:

A cricket who’s been watching him shows him that he actually can dance. He just needs his own music. And once he starts breaking it down in that jungle clearing, all the animals who laughed at him earlier show up and start cheering him on.

Resolution:

Gerald finishes with a bow and teaches the other animals (and us) an important lesson.

September 19, 2015

Can You Break Grammar and Punctuation Rules and Still be a Good Writer?

Note: This is an online version of a writing workshop currently in progress: Learning, Then Burning (Or at Least Overturning) the Writing Rule Book. You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

In the pre-class questionnaires, I asked which writing “rules” people wanted to discuss. Several students mentioned grammar and punctuation. Can you break the rules that your English teachers have spent years of sweat and tears reinforcing and still be a good writer?

As an English teacher myself, I hate to say yes, but… yes. It’s possible. And when it works, it works very, very well.

Here are three examples of authors who have broken the rules of grammar and punctuation and been very successful. You can use the links and Amazon’s “look inside” feature to read excerpts from the books. As you read, think about what the authors achieve by choosing to break these rules.

Angela’s Ashes

by Frank McCourt

(Pulitzer Prize Winner and New York Times #1 bestseller)

Book description: This is a memoir of the author’s self-described “miserable Irish childhood,” with a focus on his mother, Angela.

Click here to view the book on Amazon and read the first few pages using the “look inside” feature.

The excerpt we discussed in class begins with these words:

Malachy, at the far end of the bar, turned pale, gave the great-breasted ones a sickly smile, offered them a drink. They resisted the smile and spurned the offer. Delia said, We don’t know what class of a tribe you come from in the North of Ireland.

Philomena said, There is a suspicion that you might have Presbyterians in your family, which would explain what you did to our cousin.

Broken rule: There is quite a bit of non-standard grammar in here, and there are no quotations around any of the dialogue in the entire book.

What the author achieves by breaking this rule: We discussed this in more detail in class, but three things we discussed are worth mentioning here: All students in class agreed that they felt like they “heard” an Irish accent as they read, and one student said she could hear the speed and noise of the argument in the bar between Angela’s sisters, their husbands, and Malachy.

The Brief, Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

By Junot Diaz

(Pulitzer Prize Winner and Macarthur Genius Grant Winner)

Background for the excerpt: We began with the first chapter after the prologue, “Ghetto Nerd at the End of the World.” In this, we meet our main character, a nerdy Dominican kid named Oscar De Leon who lives in New Jersey. The narrator is his older sister’s boyfriend, who is also Dominican, and also from New Jersey. But he’s the type of guy who has much more luck with the ladies than Oscar.

Click here to view the book on Amazon and read the first few pages using the “look inside” feature.

The excerpt we discussed begins with these words:

Our hero was not one of those Dominican cats everyone’s always going on about- he wasn’t no home-run hitter or a fly bachatero, not a playboy with a million hots on his jock.

And except for one period early in his life, dude never much luck with the females (how very un-Dominican of him).

He was seven then.

Broken rule: The narrator uses slang and non-standard grammar throughout the book.

What the author achieves by breaking this rule: Authentic voice and personality of the narrator. Even though the narrator isn’t a huge character in most of the story, we always know the story is being filtered through his perspective, and that he brings his own personality to it.

Happy Are the Happy

Yasmina Reza

(Internationally acclaimed novelist and playwright)

Background of excerpt: This book (translated from the French original) features chapters from points of view of about 15 different characters, but the couple that begins the book and links everyone together are Robert and Odile Toscano, featured here on the first page.

Click here to view the book on Amazon and read the first few pages using the “look inside” feature.

The excerpt we discussed begins with these words:

We were at the supermarket, shopping for the weekend. At some point she said, you go stand in the cheese line while I get the rest of the groceries. When I came back, the shopping cart was half filled with boxes of cereal and bags of cookies and packets of powdered food and other deserts. I said, what’s all this for? – What do you mean, what’s all this for? I said, what’s the point of buying all this?

Broken Rules: No paragraph structure. No quotation marks around dialogue.

What the author achieves by breaking this rule: Captures the energy of the conversation. You feel like you can here these people arguing in front of you in line at the supermarket.

As we discussed all three of these excerpts, we were able to identify three main reasons authors sometimes break the rules of mechanics on purpose:

Memory – Memoir-writers in particular are conscious that they might not remember things exactly as they happened. Leaving out quotations is a way of saying, hey, I might not have this dialogue exactly right, but here’s the way I remember the conversation happening. (If you want to hear a great interview about this, here’s a link to memoirist Mary Carr discussing this on NPR.)

Energy – When conversations involve multiple people interrupting each other, or when a scene has a lot of static and background noise, playing with punctuation can help the writer stay true to the energy level of the situation they hope to capture.

Authenticity – In our daily lives, most of us don’t use perfect sentence structure while speaking. This is even more true for people who learned English as a second language or have a strong regional accent or use a lot of slang. To truly capture a character’s voice and personality, the author has to capture their rhythm, word choice, and grammar – which often means breaking grammar rules. Many authors do this when writing dialogue, but if the narrator has a personality of his or her own, as in Junot Diaz’s book, it can also make sense to write the whole book the way the narrator would say it aloud.

***WRITING EXERCISES***

Playing with memory: Think back to the last conversation you had that lasted more than five minutes. Start with the words, I’m not sure if I remember this exactly right… Then try to recreate the conversation on the page, but don’t put quotation marks around any of the dialogue.

Channeling energy: List a few moments in your memory that seemed like they went much more quickly than they actually did. Then list a few moments that seemed to happen much more slowly than they actually did. Pick a moment from one of the lists* and describe it – aim to capture the speed that the moment felt like it happened rather than the speed of the actual moment.

*If you like this exercise, try it again with a moment from the opposite list.

Capturing authenticity: Think of a person you know pretty well who has a distinctive way of speaking. What is something this person likes to talk about? Pick up your pen (or keyboard) and let them talk through you.*

*Tip: Try not to spell out accents phonetically. This can be confusing to readers. Word choice, word order, and sometimes punctuation can do a much better job of helping readers “hear” an accent in their heads. (See example above from Frank McCourt.)

+++++

This is an online version of a writing workshop by Roxanna Elden, author of See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers. (And hopefully some other books, soon.)

You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

How to Use Goodreads and TVtropes to Improve Your Writing

Note: This is an online version of a handout from a writing workshop currently in progress: Learning, Then Burning (Or at Least Overturning) the Writing Rule Book. You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

GoodReads.com

What it is: A free site that lets you record, catalog, and organize the books you’ve read and want to read. It also lets you see what friends are reading and makes book recommendations based on books you’ve already read.

How to use Goodreads to improve your writing: Start an account. Add the books you’ve read. Make bookshelves for writing traits you admire and types of writing you enjoy. For example, you can have a shelf for good characterization, poetic language, suspense, or historical fiction. Note that the same book can be on multiple shelves, so if your favorite historical fiction also uses poetic language, the book can serve as an example of both. As you write, when you feel that you need an example of a certain type of writing, click on the bookshelf and look through the titles to see what might be useful.

How to use Goodreads in a class on breaking writing rules: Specifically pay attention to the books that have broken certain rules and put them in categories. This way you have a ready catalogue for writing models and reassurance that you are in good company. As an example, here is my shelf for books that break common writing rules.

TVtropes.org

What it is: “Tropes” are storytelling devices and conventions. TVtropes.org is a writing-related wiki site, which is a site like Wikipedia that invites contributions from lots of users.

How to use TVtropes.org to improve your writing: Look up your favorite movies and TV shows. Look at the devices used in them. Then read the list of other TV shows and movies that have used the same trope.

How to use TVtropes.org for a class on breaking writing rules: sometimes you will see that a trope has been “subverted,” which means broken on purpose. Here is the definition of “Subverted Trope” on TVTropes. The examples using the car chase and sheet of glass are especially helpful. Below that you will see examples of subverted tropes in a variety of TV shows and films. It’s also worth checking out “Not a Subversion,” which explains other ways of breaking rules such as “inverted trope,” “averted trope,” and “justified trope.”

++++

This is an online version of a writing workshop by Roxanna Elden, author of See Me After Class: Advice for Teachers by Teachers. (And hopefully some other books, soon.)

You can sign up here to receive notes from this class as they become available.

September 13, 2015

Interpreting Common Teacher Nightmares: A Totally Unscientific Guide

I’m a believer that images from a night’s sleep can provide insight into daytime thoughts, so it’s always been interesting to me that so many teachers report having similar dreams — or, in many cases, similar nightmares. With the help of my yellowed copy of Tony Crisp’s Dream Dictionary and conversations with a few colleagues, I’ve prepared a completely unscientific, non-research-based guide to images from common teacher nightmares. Don’t be surprised if you recognize some of the scenarios below.

You show up to work in a bathrobe/your pajamas/the clothes you went out in last night. Teachers usually report having this dream not only in August, but a few nights before the end of any break. According to the Dream Dictionary, being undressed in a dream represents vulnerability and the fear that one’s weaknesses are exposed. Ragged or inappropriate clothes can represent feelings of inadequacy. Both of these relate to the fear that you are unprepared. Whatever you are — or aren’t — wearing in this type of dream, it’s probably your inner teacher clock saying, “Hey, start thinking about whether you’re ready for your first day back!”

You are already running late. Then you get lost on your way to school. The Dream Dictionary says dreams about being late can mean avoidance of responsibility, but there is a chance that this one can be taken literally: Maybe you are scared of being late on an important day of school. And of course you should be. Even if you’re sure everything is laid out as you want it, you want a head start so you can be there before your first early-bird student.

Your subject or grade level has been changed at the last minute. Teaching requires lots of advanced preparation, but also the flexibility to deal with last-minute changes. It can be tough to deal with this contradiction. After all that work setting up a hands-on science center for your 2nd graders, it’s natural to worry about a sudden change to your teaching assignment.

Students show up at your house. This dream is most likely to occur right after you hit the snooze button. It involves a group of students showing up at your house, sometimes coming inside to help themselves to bowls of cereal from your kitchen cabinets while you try to think of something to keep them busy. This dream is probably a sign that you’re worrying about your students even when you’re not at school. It’s also probably your subconscious telling you that when your alarm rings a second time, you better not hit snooze.

You are in a physical fight with a student, fellow teacher, or administrator. On a figurative level, fight dreams can express your desire to defend your honor, values, or personal space. Other interpretations are more straightforward: Violent dreams can show anger, frustration, or even a genuine desire to hurt the colleague who stole your lunch from the teachers’ lounge, the administrator who criticized you in front of your students, or the kid who WON’T STOP TAPPING HIS PEN WHILE YOU ARE TRYING TO GIVE DIRECTIONS. In fact, in some cases, teachers report that these “nightmares” can show up as daydreams.

Your classroom is in the cafeteria, an open field, or an irregularly shaped room where you can’t see all of your students, and they can’t hear anything you say. This is unfortunate, because you often have about 250 students in this type of dream, including every bad kid you’ve ever seen, and even bullies from your own school days. Psychologists in a documentary called “What Are Dreams?” say that nightmares are our brain’s way of preparing for situations even worse than our worst-case scenario. This applies here: After spending the night imagining an L-shaped auditorium with hundreds of children, your rectangular class of 30 should seem a little less scary.

Even your worst nightmares are just your brain doing its thing to help you become a better teacher. That should be reason enough to get a full night’s sleep whenever possible. If not, remember that dealing with 30 kids on only a few hours of sleep really can be a nightmare.

September 10, 2015

Faking It ‘Til You Make It: Tips for Looking Less Like a Rookie Teacher

“Is this your first year as a teacher?”

There are only a few possible answers when a student asks this dreaded question. All of them are wrong. You can tell the truth, thus opening the door to the tests students save for new teachers. You can mumble some vague answer that makes your training program or summer as a camp counselor seem like teaching experience. The best bad response is often a question that changes the subject, like, “Are you working on your math problems?” Then, walk to your desk and shuffle papers until the moment passes.

No matter what your answer, however, the question above can leave you paranoid and wondering how students picked up on your rookie status so quickly.

Part of the secret is that no matter how prepared you are, some aspects of teaching develop with experience. The list below explains some of these – plus a few tips for faking them in the meantime.

Confidence: It’s hard to feel self-assured as a beginner, and nothing messes with your confidence like someone telling you to “be confident!” Luckily, there are some concrete things you can do to give yourself a psychological edge. Get to school before your students do. Have materials laid out in advance when possible. Keep your cell phone silent, your private life private, and your language school-appropriate. These actions show you mean it when you say class time is for class activities.

A sense of what can wait until later: Experienced teachers know what to do with the binder they just got from training, hand-me-down workbooks from a retiring colleague, or materials from their school’s orientation. They know some of these things can wait, and in some cases, they won’t get used at all. Beginners are more likely to add all new materials to a giant pile of things they think they need to do urgently. A quick fix for this is an “Ideas for the Future” box in your classroom closet. Use it to store anything that is potentially useful, but not enough of a priority to keep on your desk.

The “teacher look:” You’ve likely already heard of the “teacher look,” that one-second glance that taps the brakes on bad behavior. This look is muscle memory for veteran teachers, but is so individual it is hard to copy. A starting point is to pull up a pre-selected image from your past that made you feel ready to jump out of your seat and choke someone. That feeling – and that readiness – is the driving force behind a successful teacher look. The good news is that once you’ve taught for a while you’ll have lots of those memories stored away, and your teacher look will come naturally, too.

Procedures for most daily routines: Good routines prevent minor annoyances and sometimes even major behavior problems. Teachers around you have developed procedures for everything from bathroom visits to sharpening pencils. Unlike the teacher look, you can easily copy procedures from other teachers. Just be ready to adapt them to your style and students.

A Few Success Stories Under Their Belts to Keep Them Going: All teachers have bad days, and rookies tend to be harder on themselves than veterans. This is partly because experienced teachers have stored enough good memories to reassure themselves and balance out the moments that make us wonder if we’re cut out for this. Just remember that the longtime teachers on your hallway have probably hit similar low points and chose to keep teaching anyway… and if that’s not an argument for the rewards of this profession, nothing is.

Teacher lines: Teachers don’t always have time to think of original comebacks, but experienced educators often have a supply of pre-loaded remarks for common situations. It can be difficult to plan these in advance; our best lines usually stem from comments we think of fifteen minutes after we should have used them. Every now and then, however, you can anticipate a scenario and prepare your response. You can start by thinking of what you’ll say when someone asks, “Is this your first year as a teacher?”