Oxford University Press's Blog, page 347

July 11, 2017

Jane Austen and the Voice of Insurrection

Mark Twain was notoriously unimpressed. “I often want to criticise Jane Austen,” he fumed with flamboyant but heartfelt irritation. “Every time I read Pride and Prejudice I want to dig her up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone!”

Twain’s furious rejection of Austen’s world reveals his deep allegiance to a very different literary tradition, a tradition that prizes individual ambition over public engagement, uncharted territory over social convention, and adventurous masculinity over traditional femininity. Ironically, of course, what Twain found so provoking—Austen’s preoccupation with domesticity, elegance, and courtship—are the same qualities that have won her legions of devoted fans, many of whom read her novels as comfy escapism, where not even the political strife of contemporary England or the horrors of the Napoleonic Wars ravaging Europe are allowed to disrupt the course of true love, or the inevitability of a happy ending.

Both camps have a point. Austen’s six published novels are not as claustrophobic as Twain’s outburst suggests, but they are all poised and tightly constructed comedies of manners that centre on the commonplace, apparently trivial, events in the lives of “3 or 4 Families in a Country Village,” as Austen herself acknowledged in a letter to her niece of September 1814. Austen’s fandom, too, is right to insist that no one tells a love story like Jane Austen. Her novels are all swoon-inducing tales that feature handsome men, pretty women, witty dialogue, and elaborate codes of propriety, and they all focus on a hero and heroine who overcome various obstacles in order to find richer versions of themselves and joy in each other. Famously, in the case of Pride and Prejudice, Austen herself fretted that it was “rather too light & bright & sparkling,” though she stood by her heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, whom she considered “as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print.”

Austen’s mastery of domestic comedy and romantic wish-fulfillment accounts in part for her enduring popularity. But as we mark the two hundredth anniversary of her death, it is her other achievements as a novelist that have even greater claims upon our attention, and that have also shaped her status as one of our most important writers. Austen, observed Virginia Woolf, was “mistress of much deeper emotion than appears upon the surface,” for beneath the shimmering veneer of all her novels lie pressing questions concerning class, money, matrimony, sexual attraction, and female subjugation. Spinsterhood haunts many of Austen’s women, as do the very real threats posed by loss of reputation, abandonment, poorly-paid employment, and poverty, to say nothing of the small number of years they have to secure a partner before they are deemed too old and forced onto the shelf by younger rivals. Better than anyone else either before or since, Austen wrote novels that combine romance with satire, and fairy-tale enchantment with bitter social realism. She knew that our biggest hopes sometimes rest on the smallest events, and that tragedy can be played out, not just on a national stage or a foreign battlefield, but on a country walk or during a drawing-room conversation.

Austen, observed Virginia Woolf, was “mistress of much deeper emotion than appears upon the surface,” for beneath the shimmering veneer of all her novels lie pressing questions concerning class, money, matrimony, sexual attraction, and female subjugation.

In Pride and Prejudice, as Twain’s rancour suggests, Austen examines all of these issues with disarming clarity, and especially in two of the novel’s most celebrated scenes, both of which demonstrate her remarkable ability to blend passionately-felt private emotion with much larger cultural and political concerns. In the first, the novel’s haughty, smouldering hero, Mr Darcy, makes Elizabeth what is—at least in his own mind—a very romantic proposal of marriage, and he does so entirely confident that she will accept him. Yes, he knows he should not be even contemplating such an offer. Her social and economic situation in life is so far below his own as to be a degradation to him. But how very satisfying it must be now for her to learn that he cannot help himself. His love for her is overwhelming. He would like her to be his wife. This is the gist of what he tells her.

The comeuppance she gives him is unforgettable. Darcy is very pleased to think of himself as an English “gentleman,” but he has fallen in love with a woman who simply does not accept that his land, money, and rank equal respectability, or that because of them he is entitled to think of himself as her superior. When she refuses him, she states that she might have felt more concern had he “behaved in a more gentleman-like manner.” Those words literally stagger him. They signal a powerful collision between his elitist assumptions and her bourgeois aspirations. Darcy thinks that he was born a gentleman. Elizabeth hopes that someday he might become one. He is stuck in the past. She can see the future. She believes in meritocracy over aristocracy, individual preference over dynastic alliance, and female desire over male presumption.

In the second scene, Darcy’s dreadful aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, confronts Elizabeth over her possible engagement to Darcy, and insists that she give up any idea of quitting the sphere in which she has been brought up. Elizabeth is not about to be pushed around by a snob. “In marrying your nephew, I should not consider myself as quitting that sphere,” she retorts. “He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman’s daughter; so far we are equal.” Not in Lady Catherine’s eyes. “Who was your mother? Who are your uncles and aunts?” she lashes back, before recoiling at the notion that someone of Elizabeth’s status might in any way be allied with her nephew’s property: “Are the shades of Pemberley to be thus polluted?” she sneers. Elizabeth is shaken but unbowed by the exchange, and parts from Lady Catherine with her dignity intact.

The American critic and novelist William Dean Howells was a close friend of Mark Twain, but he had an entirely different opinion of Austen, and he knew what was at stake in Elizabeth’s showdown with Lady Catherine. Elizabeth “is much more a lady than her ladyship,” Howells declares, and “it is impossible…not to feel that her triumph over Lady de Bourgh is something more than personal: it is a protest, it is an insurrection.” In Pride and Prejudice, he adds, “an indignant sense of the value of humanity as against the pretensions of rank, such as had not been felt in English fiction before, stirs throughout the story.” Austen in her novels took village comedy to unparalleled levels of sophistication, and told love stories that still have the ability to charm and move us two centuries later. But she also matters now, and perhaps more than ever, because of her fierce and unwavering moral anger, especially concerning the way women are treated. In Elizabeth Bennet, she gives us not only her most memorable heroine, but also a woman who has the courage both to stare down condescension and intolerance, and to speak up for self-respect, gender equality, and the value of humanity.

Featured image credit: “English British Country” by GerDukes. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Jane Austen and the Voice of Insurrection appeared first on OUPblog.

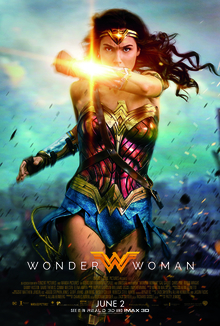

Wonder Woman and the realities of World War I

Wonder Woman takes place in an alternative universe, yet the new film of the same name is set in a recognizable historical context: the First World War. For historians, this provides a chance to compare myth to reality. Putting aside the obvious and deliberate alterations—Erich von Ludendorff’s depiction in the story—the film touches on several of the themes that scholars still debate today regarding war and gender.

Diana Prince’s mission to defeat war shores up the myths that dominate the history of the First World War, both its claim to be in the words of sci-fi writer H.G. Wells, “the war to end all wars” and the most terrible and destructive war that the world had ever seen. Steve Trevor is portrayed as the honorable American doughboy with high-minded principles who is, of course, an aviator. The “Knights of the Air” continue to be a fascinating trope in popular narratives and films about the war, offering a new form of the military masculine ideal.

The film also replicates some myths about women. While we see passing images of women as nurses or munition workers in the train station, we mostly see women as victims, part of the hybrid “womenandchildren” as feminist scholar Cynthia Enloe characterizes it. They stand in for the “innocent” lives that the new weapons of war destroy. Certainly scenes of refugees fleeing the violence of the fronts in Belgium reflect the reality of war’s devastation, but only Wonder Woman seems to have a job to do in this war; none of the other myriad roles for women in work and voluntary sectors is truly depicted. In addition, the film acts as if the only place women and children were threatened was in Europe, ignoring both the consequences of this war for women of color in Africa, Asia and the Americas, and their participation.

Wonder Woman (2017 film).jpg by Warner Bros. Pictures. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.

Wonder Woman (2017 film).jpg by Warner Bros. Pictures. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.The story of the war here also shares much with Allied propaganda of the time, including its dark portrayal of German women. The only woman who matters on the German side is Dr. Poison, a mad female chemist who takes delight in concocting ever more lethal gases. Dr. Poison is reminiscent of the real German World War I female spymaster, known in propaganda as the Fraulein Doktor, who features in films of the 1930s and a 1969 Dino de Laurentis film. The Fraulein Doktor seems sure to have inspired the broad outline for Dr. Poison.

In her attitude of unthinking cruelty, Dr. Poison also mirrors the German nurse of an infamous WWI poster: “Red Cross or Iron Cross,” which depicts a German nurse pouring a glass of water on the ground rather than give it to the injured English soldier who cries out in pain and thirst. The poster exhorts the woman of England to take action by claiming that no one from their nation would ever act so maliciously.

Dr. Poison also wears a replica of the tin masks designed and painted to disguise the appalling facial injuries suffered by male combatants. That such masks were created by American women artists such Anna Coleman Ladd as part of a vast network of women motivated to relieve the sufferings of war seems ironic. See actual footage of her studio.

One of the more intriguing aspects of the story is its focus on chemical warfare. In contrast to the film, the chemical weapons of the First World War were invented by men, but chemical shells (like the gas masks designed to protect against them) were produced in factories staffed by women. It’s worth noting that the most famous women chemists of the First World War era were those like Dr. Getrud Woker, who made it their mission in the aftermath of the war to try to halt chemical weapons as well as air power. After the war, Woker and her fellow scientist Dr. Naima Sahlbom, formed what became the “International Committee Against Scientific Warfare,” committed to trying to eradicate this weapon of mass destruction. They confronted politicians and scientists in a war of words and petitions.

Another interesting parallel between Wonder Woman and the women of World War I is that female soldiers participated in combat, notably the Women’s Battalion of Death in 1917 Russia under the Provisional Government. One of the big differences, however, is that these women deliberately rejected the glamour of Gal Gadot; they shaved their heads and desexualized their appearance in order to be treated seriously as soldiers.

To wear a revealing outfit and have your hair down such as Wonder Woman does risked being treated as sexually available, increasing the danger of harassment and rape. These very real threats to women in war are merely hinted at in a scene in the movie when Trevor intervenes in a short exchange between Diana and a group of soldiers. Diana’s power and lack of fear of men in the film suggests the alternative universe of the comic, not the reality of life for women in conflict zones.

The film’s Diana Prince is an interesting exemplar of the tensions not only of the war but of femininity under fire in many eras. Despite all of her kickassness, Wonder Woman can be distracted by a baby or motivated solely by a mother and child in distress. Her raison d’être is both the need to destroy war and to defend the innocent.

Her reaction to war thus in a way mirrors most closely not those of the actual women close to the frontlines, but that of the feisty minority of women—many formerly active in the women’s suffrage campaign—who protested against the war and argued as mothers of soldier sons and as future victims of future wars.

Wonder Woman and Woodrow Wilson both discovered the difficulties of fighting war to end war. We hope the crowds flocking to the film may be inspired by it to explore the ways in which men and women both actively engaged in the war and sought to secure peace and the amelioration of suffering.

Headline image credit: Arbeiten zur inneren Ausrüstung der Gasmasken, wie Einarbeiten des feinen Drahtgeflechts und Auskleiden der Innenwände mit Sand etc. by Unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Wonder Woman and the realities of World War I appeared first on OUPblog.

July 10, 2017

Radio telescopes to detect gravitational waves

Sensationally detected for the first time by the LIGO instrument in 2015, gravitational waves are ripples in space-time – the continuum of the universe – that propagate outward from astrophysical systems. The question is: can we find more of these gravitational waves and do it regularly? Some years ago we have devised a method of finding far more of them, and from weaker sources, than is possible with present techniques with the help of radio telescopes and natural astrophysical masers. Gravitational waves were predicted by Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, which describes how the universe is shaped (curved) by gravitational fields. If a catastrophic event like the destruction of a star takes place, a burst of gravitational waves propagates outwards at the speed of light.

By the time they reach the Earth, gravitational waves have often travelled across millions of light years of space. They are then extraordinarily weak disturbances, and for more than half a century the direct detecting of gravitational waves was a challenge for physicists.

Finally, the first event detected by the LIGO team required the interferometer with four-kilometer-long arms to change their length by a fraction of the size of a proton – such is the ‘displacement’ that must be registered. Despite this, LIGO is expected to detect many more events once it enters full operation in 2020.

In order to escape waiting for a catastrophic event which produces such a tiny signal, a principally different idea of registering gravitational waves was proposed. A wave affects not only a macroscopic body but a free atom or molecule as well. If this perturbation is long enough and periodic, and the atoms belong to an astrophysical maser – short for “Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation” – the maser signal obtains a specific ‘non-stationary’ feature whose amplitude has the same order as the signal itself and which can be detected by processing the signal of the radio telescope.

In space we find natural astrophysical masers formed by clouds of various molecules located near stars. The radiation from the star stimulates the molecules, until they emit radiation at a specific frequency. This propagates through the cloud, stimulating other molecules and building up a strong source detectable by radio telescopes on Earth.

The Radio Astronomy Observatory of Russian Academy of Science in Puschino, Russia – a place where they listen to stars. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Radio Astronomy Observatory of Russian Academy of Science in Puschino, Russia – a place where they listen to stars. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Two close stars in orbit around each other in so-called binary systems are a source of weak and strictly periodic gravitational waves. It turned out that in certain circumstances the waves from such a binary system will affect the output of an astrophysical maser. The maser signal acquires the non-stationary component with the same frequency as the gravitational wave, in a direct relation to the time taken for the two stars to complete each orbit.

Through our investigations, we have found more than thirty cases where masers influenced by gravitational waves from binary star systems show evidence for this effect. Unlike the dramatic events needed for a LIGO detection, radio observatories could now find continuous sources of gravitational waves.

But our technique can take things further by using masers and binary stars as beacons of gravitational waves. Comparing the different systems will then give us an entirely new way of testing the properties of space-time.

We now invite radio observatories around the world to test these ideas.

Featured image credit: Gravitational Waves of a compact binary system by MoocSummers. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Radio telescopes to detect gravitational waves appeared first on OUPblog.

Queen’s University Belfast win the OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition 2017

Congratulations to the Queen’s University Belfast team represented by Darren Finnegan and Conor Lockhart, who were crowned champions of the OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition 2016-2017, which took place at BPP Law School, Holborn on 22 June 2017.

His Honour Judge Gratwicke returned once again to preside over the final and kept the students on their toes with some keen questioning. He remarked that he was amazed and humbled by the high standard of mooting he had witnessed, noting that the difference in marks between all four teams could be counted on one hand.

The fictitious moot problem was devised for the final by barrister Rory Clarke, and focused on property law but also touched on the issues of Brexit and ownership of street art. The problem provided all participants with the opportunity to showcase their legal knowledge and advocacy skills.

The other three teams to progress to the final were Sheffield Hallam University represented by Billy Methley and Millie Broadbent; University of Buckingham represented by Joshua Cullen and Yashwanth Krishnan; and University of East Anglia, represented by Polly Averns and Anne Saunderson, all of whom worked incredibly hard to reach the final of the competition, often juggling mooting with coursework deadlines and exams.

Darren Finnegan and Conor Lockhart received a certificate, trophy, and £750 each. Joshua Cullen and Yashwanth Krishnan finished second and share £700 between them.

We send our thanks to all the participants who took part this year, together with the mooting co-ordinators and academics who train and coach their students.

Attendees mingle at the drinks reception

Judge Gratwicke delivering his speech

Queen's University Belfast are announced the winners

Judge Gratwicke with the 2016-17 finalists

The 2016-2017 mooting runners-up

The 2016-17 mooting champions

All images courtesy of Oxford University Press.

The post Queen’s University Belfast win the OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 9, 2017

Who needs quantum key distribution?

Chinese scientists have recently announced the use of a satellite to transfer quantum entangled light particles between two ground stations over 1,000 kilometres apart. This has been heralded as the dawn of a new secure internet.

Should we be impressed? Yes – scientific breakthroughs are great things.

Does this revolutionise the future of cyber security? No – sadly, almost certainly not.

At the heart of modern cyber security is cryptography, which provides a kit of mathematically-based tools for providing core security services such as confidentiality (restricting who can access data), data integrity (making sure that any unauthorised changes to data are detected), and authentication (identifying the correct source of data). We rely on cryptography every day for securing everything we do in cyberspace, such as banking, mobile phone calls, online shopping, messaging, social media, etc. Since everything is in cyberspace these days, cryptography also underpins the security of the likes of governments, power stations, homes, and cars.

Cryptography relies on secrets, known as keys, which act in a similar role to keys in the physical world. Encryption, for example, is the digital equivalent of locking information inside a box. Only those who have access to the key can open the box to retrieve the contents. Anyone else can shake the box all they like – the contents remain inaccessible without access to the key.

A challenge in cryptography is key distribution, which means getting the right cryptographic key to those (and only those) who need it. There are many different techniques for key distribution. For many of our everyday applications key distribution is effortless, since keys come preinstalled on devices that we acquire (for example, mobile SIM cards, bank cards, car key fobs, etc.) In other cases it is straightforward because devices that need to share keys are physically close to one another (for example, you read the key on the label of your Wi-Fi router and type it into devices you permit to connect).

GPG Passphrase by Linux Screenshots. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

GPG Passphrase by Linux Screenshots. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Key distribution is more challenging when the communicating parties are far from one another and do not have any business relationship during which keys could have been distributed. This is typically the case when you buy something from an online store or engage in a WhatsApp message exchange. Key distribution in these situations is tricky, but very solvable, using techniques based on a special set of cryptographic tools known as public-key cryptography. Your devices use such techniques every day to distribute keys, without you even being aware it is happening.

There is yet another way of distributing keys, known as quantum key distribution. This uses a quantum channel such as line of sight or fibre-optic cable to exchange light particles, from which a cryptographic key can eventually be extracted. Distance limitations, poor data rates, and the reliance on specialist equipment have previously made quantum key distribution more of a scientific curiosity than a practical technology. What the Chinese scientists have done is blow the current distance record for quantum key distribution from around 100kms to 1000kms, through the use of a satellite. That’s impressive.

However, the Chinese scientists have not significantly improved the case for using quantum key distribution in the first place. We can happily distribute cryptographic keys today without lasers and satellites, so why would we ever need to? Just because we can?

Well, there’s a glimmer of a case. For the likes of banking and mobile phones, it seems unlikely we will ever need quantum key distribution. However, for applications which currently rely on public-key cryptography, there is a problem brewing. If anyone gets around to building a practical quantum computer (and we’re not talking tomorrow), then current public-key cryptographic techniques will become insecure. This is because a quantum computer will efficiently solve the hard mathematical problems on which today’s public-key cryptography relies. Cryptographers today are thus developing new types of public-key cryptography that will resist quantum computers. I am confident they will succeed. When they do, we will be able to continue distributing keys in similar ways to today.—in other words, without quantum key distribution.

Who needs quantum key distribution then? Frankly, it’s hard to make a case, but let’s try. One possible advantage of quantum key distribution is that it enables the use of a highly secure form of encryption known as the one-time pad. One reason almost nobody uses the one-time pad is that it’s a complete hassle to distribute its keys. Quantum key distribution would solve this. More importantly, however, nobody uses the one-time pad today because modern encryption techniques are so strong. If you don’t believe me, look how frustrated some government agencies are that we are using them. We don’t use the one-time pad because we don’t need to. The same argument applies to quantum key distribution itself.

Finally, let’s just suppose that there is an application which somehow merits the use of the one-time pad. Do the one-time pad and quantum key distribution provide the ultimate security that physicists often claim? Here’s the really bad news. We have just been discussing all the wrong things. Cyber security rarely fails due to problems with encryption algorithms or the ways that cryptographic keys are distributed. Much more common are failures in the systems and processes surrounding cryptography. These include poor implementations and misuse. For example, one-time pads and quantum key distribution don’t protect data after it is decrypted, or if a key is accidentally used twice, or if someone forgets to turn encryption on, etc. We already have good encryption and key distribution techniques. We need to get much better at building secure systems.

So, I’m very impressed that a cryptographic key can be distributed via satellite. That’s great – but I don’t think this will revolutionise cryptography. And I certainly don’t feel any more secure as a result.

Featured image credit: Virus by geralt. CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post Who needs quantum key distribution? appeared first on OUPblog.

Let your soul escape: send a postcard this summer

‘The politics of postcards’ is not a common topic of conversation or academic study but as the summer approaches, my mind is turning to how I can continue to write about politics from the seaside, campsite, or dreary ‘Bed & Breakfast’ hotel. Could the humble postcard possibly offer a yet under recognized outlet for political expression? A 6” by 4”’ inch canvas on which to turn political writing into an art form?

To talk of postcards in a vaunted age of ‘digital democrats’ and ‘24/7 instant communication’ might appear somewhat antiquated, even quaint, but the resilience of the postcard as a political medium, as a mode of mass communication, in both developed and developing countries around the world, suggests that there is something quite special about this form of interaction.

“Everyone loves to get a postcard!” my mother used to say as she encouraged, coaxed, and forced me into writing countless postcards to friends and relatives during family holidays around the United Kingdom.

To understand ‘the politics of postcards’, however, and specifically what endows them their special qualities as both an expressive act and an act of expression, there is a need to look beneath their physical form, their instrumental value and their mass-produced messages. An argument could be made – indeed, will be made – that the deeper value of postcards and their political significance lies in the nature of the writing they commonly capture and in their … simple brevity. To write a postcard is therefore to unwittingly strip down one’s thoughts and engage in a possibly more honest and direct form of writing. The paradox here is that if politics is defined through the dominant contemporary lens of negativity, then political writing would itself be automatically associated with mendacity, falsehoods, and half-truths. To make this point is to work within the contours of George Orwell’s famous essay of 1946, ‘Politics and the English language’, and his argument about political language making ‘lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.’ Orwell sought to encourage concreteness and clarity instead of vagueness, and in many ways the brevity of the postcard encourages honest precision.

Put slightly differently, the paradox of postcards is that their physical form promotes straight talking (possibly, straight-writing), and through this, arguably offers a more honest and engaging account: ‘Weather poor, hotel terrible, having a good time, missing you loads.’ The argument, first developed in French by Blaise Pascal in 1657 and later popularised by Mark Twain in a letter of 1871, that it can take longer and be harder to write a shorter letter than a longer one, speaks to the demands of stripping down one’s thoughts and clarifying one’s arguments; far easier to avoid such strenuous and potentially risky endeavours by hiding one’s views within a sea of knowledge claims, counter-claims, and caveats.

Could the humble postcard possibly offer a yet under recognized outlet for political expression?

The link between this argument, those of Orwell, and contemporary scholarship is provided by Michael Billig’s caustic Learn to Write Badly: How to Succeed in the Social Sciences (2013), but my argument here is really about the manner in which postcards by their very nature command a certain sense of clarity and precision, possibly even honesty, and certainly a sense of timelessness. This may not, of course, be the case in relation to modern mass-produced political campaign literature for the simple fact that they are neither written from one person to another, and nor do they have any subjective or personal quality. They are thin and shallow pieces of card. They are an element of modern machine politics that too often focus on telling you what is ‘wrong’ with the opposition’s candidates or other parties, and too little about what is ‘right’ about the actual sender of the card.

The same might be said for the pre-printed postcards distributed by a vast range of special interest organisations and pressure groups to their members on the basis that, with the addition of their signature, they should be dispatched (first class) to the relevant politician. This represents a significant shift in the use and abuse of political postcards as they were traditionally used to promote a specific argument, candidate, or vision rather than as a tool of political warfare within an increasingly grubby form of ‘attack’ or one-dimensional politics.

We might, then, separate political postcards into many a number of discrete forms. There are Big ‘P’ political postcards of the sort sent by candidates and parties, which in modern times tend to be blunt, impersonal, and cosmetic,. and may, However, as a result, these may form one small element of a wider story about the rise of disaffected democrats, critical citizens, and the professionalisation of politics.

Although apparently precise and direct in terms of tone and style, I am confident that Orwell would have much to say about these Big ‘P’ political postcards and their murky relationship with the English language in terms of honesty. Against this one can imagine a second category of small ‘p’ political postcards that may be written from a mother to a son, a daughter to a granddaughter, or from one friend to another as a means of nourishing and demonstrating the existence of a relationship. These will be warm and personal and offer a degree of emotional depth or meaning – even if it is just of the ‘Weather poor, hotel terrible … missing you loads’ variety. The important point, however, is that they remain ‘political’ in the small ‘p’ sense of the term due to the manner in which they convey information and feelings, while also brokering a relationship. Postcards in the small ‘p’ sense are therefore an element of ‘everyday politics’ by which we make sense of the world around us and interpret change. (The absurdity is that political parties increasingly try to use technology in order to increasingly personalise their campaign literature, to make their Big ‘P’ postcards look and read like a small ‘p’ postcards from a friend or neighbour.)

Postcards frequently allow souls to escape. There is a therapeutic quality to writing in general, and in particular writing postcards, which stems very much from the traditional context in which they were written. Postcards are generally written on holiday when the author has space for reflection away from the pressures of day-to-day life. It is this notion of ‘headspace’ or ‘distance’ – rarely acknowledged but vital for the genre – that arguably gives postcards their personal – indeed, political – value. The small ‘p’ postcards tend to be conceived and born from a position of personal and professional distance. The fragments of thought, the messages between the lines, the issues left unspoken, the achievement of closeness while acknowledging separation, make the postcard if not a great neglected literary form then definitely one worthy of appreciation.

Featured image credit: art hanging photographs by pixabay. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Let your soul escape: send a postcard this summer appeared first on OUPblog.

Law Teacher of the Year announced at the Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching conference

Nick Clapham of the University of Surrey was pronounced Law Teacher of the Year at the Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching conference.

Oxford University Press Higher Education law team successfully hosted the conference on 29 June 2017 at the University of Warwick – bringing together nearly 100 law academics under the umbrella of celebrating teaching excellence.

Delegates were treated to sessions which ranged from the mind-blowing, to the politically charged, to the thoroughly moving. In sessions designed to be interactive delegates were able to ask questions and enter into discussions with the speakers.

At the heart of the conference were the six Law Teacher of the Year finalists who were quizzed on a panel about their motivations, inspirations, and tribulations.

Professor Lisa Webley, who won Law Teacher of the Year last year, then stepped forward to announce the winner.

The announcement came at the end of a rigorous judging process involving assessed campus visits and interviews.

On accepting his award, sponsored by Oxford University Press, Nick said,

“I am delighted and humbled to receive this prestigious award for my work at the University of Surrey. It is made even more special as OUP’s judging process means that it can only be achieved with the support of colleagues and, most importantly, students. I now look forward to the coming academic year with even greater enthusiasm for what a colleague at today’s conference rightly described as ‘one of the best jobs in the world’.”

The other finalists were:

Mohsen al Attar, Queen’s University Belfast

Michael Fay, Keele University

Matthew Homewood, Nottingham Trent University

Geoffrey Main, Thomas Bennett Sixth Form

Amanda Perry-Kessaris, University of Kent

Registration gets underway

Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching conference

Nearly 100 delegates attended the conference

Speaker Yvonne Skipper in full flow

Delegates networking

Plenty to think about at the CELT conference

Speaker Lisa Webley creates a light-hearted moment

A delegate puts a question to the speakers

Facilitator Luke Mason with the Law Teacher of the Year finalists

The delegates hear from LTOTY finalist, Amanda Perry-Kessaris

Lisa Webley announces Nick Clapham Law Teacher of the Year 2017

Nick Clapham is Law Teacher of the Year 2017

A light-hearted moment with all LTOTY17 finalists

All images were taken by Natasha Ellis-Knight of OUP, used with permission.

The post Law Teacher of the Year announced at the Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching conference appeared first on OUPblog.

July 8, 2017

The human microbiome and endangered bacteria

Each and every part of us harbours its own microbial ecosystem. This ecosystem carries some 100 billion cells, known as the microbiota. They started inhabiting our bodies 200,000 years ago, and since then we have evolved side by side to configure a balanced system in which microbes can survive in perfect harmony, provided no perturbations occur.

A number of standard methods exist for decoding their identities and genetic content. Sequencing of the 16S subunit of the bacterial ribosome from DNA reveals that there are over 5,000 species of microbes living at one with us, and that only a minor fraction, about 2%, is common to most people. By sequencing this gene from RNA, we know that not all the microbes inhabiting our bodies are active but just one in every five. Sequencing of the microbial DNA or RNA reveals that about eight million microbial genes collaborate with our genes and that only one out of 33 (or 3%) is common to most people.

Our microbiomes and their microbial products configure our innate and acquired immune system. They control the ingress of invaders, with the exception of disease, and regulate our metabolism. Therefore, imbalances in microbial and effector microbial products (genes, proteins, and molecules) may have consequences on our health.

The human microbiome is in constant evolution due to modern practices and natural factors

From birth, we establish an intimate symbiotic relationship with our microbiota. Initially the microorganisms are transferred and the relationship is maintained from one generation to the next through the birth canal. After delivery, the number of bacteria in a person’s microbiome begins to increase while simultaneously beginning to receive external influences. These perturbations may be directly linked to today’s lifestyle or to natural situations. The last 150 years have witnessed modern practices that include antibiotic and medicine intake, caesarean-section births or diets, alongside issues related to aging, confrontation with pathogens or illnesses. These factors, and many others, may have strong impacts on our microbes, even though they are highly resilient to changes. These impacts must be investigated in order to answer the question of whether changes in our microbiota are the cause or the consequence of a certain health status.

Microbes form part of us and are affected just as we are

It is highly likely that our bodies and our microbes are constantly adapting to new environments and situations together. Thus, we evolve to reach a balanced situation in which beneficial microorganisms, which keep us healthy, are favoured while pathogens are controlled.

Lactobacillus acidophilus from a commercially sold nutritional supplement tablet by Bob Blaylock. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Lactobacillus acidophilus from a commercially sold nutritional supplement tablet by Bob Blaylock. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Not all microbes are affected equally during perturbations

We have recently listed different factors (diseases, antibiotics, and others) reported to produce alterations in the microbes inhabiting our innards. They include at least 105 common or rare diseases or disorders, 68 antibiotic treatments either as a single antibiotic or cocktails, and 22 other types of factors. Illnesses produce alterations in 231 out 5,000 bacterial species inhabiting our body; antibiotics in 42 species; and other types of factors such as alcohol or tobacco consumption, medicines, and diet, to mention but a few, affect 130 species. Not all the microbes inhabiting our organism are influenced equally; however, all perturbations have one thing in common: they affect a group of bacteria essential for our bodies to work properly. These include the well-known Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Faecalibacterium, which should be considered as among the most super-sensitive species.

A step towards resolving or avoiding microbial imbalances that relate to disease and health

A growing amount of evidence has demonstrated the correlation between microorganisms that commonly keep us actively healthy, which are highly vulnerable. Thus, future actions in medicine should consider not only our protection but also prevention of the negative influences wrought by today’s lifestyle, modern practices, and other natural factors on our microbes. Options include the design of new probiotic foods enriched in some of these bacteria, special diets, or therapies favouring their growth.

Featured image credit: dna-microscopic-cell-gene-helix by typographyimages. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The human microbiome and endangered bacteria appeared first on OUPblog.

Fighting cyber crime [timeline]

The Blackstone’s Police team will soon be attending the 10th International Conference on Evidence Based Policing and 2nd Cybercrime Conference in Cambridge. In advance of the event, take a look through the timeline below to learn more about some of the key events in the recent history of cyber crime. Don’t forget to come to the Oxford University Press stand and say hello if you’re attending the conference!

Featured image credit: computer-keyboard-backlit-1869236 by CCØ BAY. CC0 Public Domain via Flickr .

The post Fighting cyber crime [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

“The lover”– an extract from Love, Madness, and Scandal

The high society of Stuart England found Frances Coke Villiers, Viscountess Purbeck (1602-1645) an exasperating woman. She lived at a time when women were expected to be obedient, silent, and chaste, but Frances displayed none of these qualities. The following extract looks Frances’ affair with Sir Robert Howard.

As her husband suffered through his increasingly frequent and severe episodes of mental illness Frances continued to struggle with her in-laws. Diversions such as her trip to The Hague with her mother no doubt presented welcome respite, but the death of her elder sister Elizabeth in 1623 added sorrow and grief to her difficulties. Increasingly, Frances sought solace in the growing and deepening relationship with the man who would come to play a central role in her life: Sir Robert Howard. By 1623, the two were lovers and the clandestine liaison triggered a whole host of new challenges for Frances.

Sir Robert Howard came from the influential and rich Howard family, but he made no mark on society. Robert was the son of Thomas Howard, Earl of Suffolk, and his countess Katherine, born Knyvet. Thomas Howard began his court career under Queen Elizabeth: she gave him a title, Baron de Walden, and he became her Lord Chamberlain towards the very end of her reign. When James came to the English throne in 1603, Thomas Howard managed to secure his position at the new court: James made him Earl of Suffolk, and he served as Lord Chamberlain from 1603 to 1613 and as Lord Treasurer from 1614 to 1618. Similarly, the Countess of Suffolk became an important and influential figure at court, serving as Queen Anna’s Lady of the Privy Chamber and Keeper of the Queen’s Jewels, receiving the very positions that Lady Hatton had so coveted. As it turned out, the rapacious greed and ambition of the Earl and Countess of Suffolk eventually led to their temporary downfall.

‘The Great Bed of Ware’ England (possibly made in Ware, Hertfordshire) by UK_FGR. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

‘The Great Bed of Ware’ England (possibly made in Ware, Hertfordshire) by UK_FGR. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.Frances and Howard’s relationship evolved from casual contacts to a romantic and sexual liaison around 1623. According to the witness depositions in Buckingham’s later investigation in the spring of 1625, Robert had ‘for the space of neer two yeers past’ had ‘verye often & familiar access to the Lady (Frances)’. At this point, Frances lived separately from John (her husband), which gave her more freedom of movement. Frances spent most of her time in Denmark House, Prince Charles’s London palace. His illness notwithstanding, John was still the Prince’s Keeper of Denmark House and as a result his wife had rooms available to her there. John, depending on the swings of his fragile nerves, split his time between treatment and isolation in the countryside and one of Buckingham’s London residences, Wallingford House.

While Frances and Howard certainly were meeting each other openly at various functions and entertainments, it was the revelations of their secretive and private meetings which later presented the damning evidence of their illicit affair. In the intense stages of an early relationship, the two lovers took great risks to be together. Howard’s frequent visits to Denmark House sometimes lasted until the early morning hours. To avoid curious eyes, Howard sneaked into Frances’s room by going through a neighbour’s house, climbing over the roof, and slipping in through Frances’s window, like an acrobatic Romeo. The couple also met secretly at the same accommodating neighbour’s house, a man named Mr Peel. It is not entirely clear why Mr Peel would allow the couple’s transgressions to take place in his house. Perhaps he was compensated, or perhaps he was a friend of Frances and Howard. The lovers had intimate suppers in their coach in Knightsbridge and at Ilford several times.

Sometimes, they left the city altogether; they went to the wells in Essex, no doubt drinking what was believed to be the holy waters. They spent nights at inns in Lambeth, Maidenhead, and Ware, where they rented rooms located right next to each other, which later interrogators interpreted as suspiciously close, although Frances and Howard claimed it was innocent. Perhaps the couple stayed at the White Heart Inn in Ware, which featured the famous Great Bed of Ware, a giant bed more than three metres wide, built as a special attraction to lure more visitors and customers to the establishment. Over the course of many centuries, overnight guests have left their marks on the bed by carving in their initials or leaving wax seals on the wooden posts. If they slept in the bed and left their marks, centuries of later couples have rendered Frances and Howard’s initials unreadable. Considering that the bed was associated with bawdy puns and stories and that it was so famous that both Shakespeare and Ben Johnson mentioned it in plays and poetry, it would have been wiser for the couple to stay somewhere more discreet and not leave any tell-tale signs behind.

Featured image credit: Somerset House, (orginally Denamark House) London, United Kingdom by Rob Bye. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post “The lover”– an extract from Love, Madness, and Scandal appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers