Pat Bertram's Blog, page 271

May 14, 2012

Wondering About Life And Death And The Meaning Of It All

I don’t think I had survivor’s guilt after the death of my life mate/soul mate, but I do feel bad that I’m leaving him behind. I get a second chance at life, new friends, new vistas, new experiences, but he has been denied that. And in fact, he was denied all those things long before his death since his protracted dying kept him from doing much except struggling to get through one more pain-filled day.

I don’t think I had survivor’s guilt after the death of my life mate/soul mate, but I do feel bad that I’m leaving him behind. I get a second chance at life, new friends, new vistas, new experiences, but he has been denied that. And in fact, he was denied all those things long before his death since his protracted dying kept him from doing much except struggling to get through one more pain-filled day.

He often told me that when he got incapacitated, I had to put him in a home and walk away. Just forget him. I know he’d want me to do the same thing now that he is dead, but I didn’t walk away when I had to put him in the hospice care center, and I can’t walk away now, and for certain I can’t just forget him.

But perhaps I am looking at the situation backward. His being dead is still the thing that drives my sadness — sadness not just for me but for him. And yet . . . what if it is he who left me behind? Perhaps he has gone on to a wondrous new life, in which case my sadness on his behalf is misplaced. And maybe none of this has anything to do with me. Maybe it’s not up to me to worry if he was cheated or not, or even to wonder if he’s in a better place. Despite our deep connection, he was still his own person. Maybe I’m poking into something that is his alone.

Just as I have to accept that my life is mine alone now.

About a year before he died, I hugged him and accidentally touched his left ear. I know now cancer had metastasized all the way up his left side and into his brain, but at the time, all I knew was that he pushed me away, wincing in agony. Something shut off right then, and a voice deep inside me said, “He might dying but I have to live.” For all that year, we went our separate ways, he to dying, me to living. Then, six weeks before he died, he made the connection with me again. He needed to talk about what was happening to him so he could gather courage to face what was coming, and during that daylong conversation, I remembered why I fell in love with him all those years ago.

Because of that disconnected year, a year where I felt dissociated from him and our life, I didn’t expect to grieve, but here I am, two years and seven weeks later, still struggling to deal with the wreckage of our shared life, still sad, still wondering about life and death and the meaning of it all. When life makes sense, death doesn’t. When death makes sense, life doesn’t. It would be nice to talk to him and compare notes about what we’re both doing, but so far he’s remaining silent.

One thing has changed recently. In between the moments of angst and wanting it all to be over with, in between the pinchings of grief and not caring what happens to me, that determination of several years ago is making itself felt.

He might be dead, but I have to live.

I just wish I knew how.

Tagged: death and grief, grief after two years, life after grief, life and death, survivors guilt

May 13, 2012

Is a Salinger-Like Reclusiveness a Viable Option in Today’s Book World?

Here’s an interesting dichotomy — there are so many books being published today that most will never sell more that 100 or 150 copies in a lifetime, yet an article in the New York Times says that in the e-reader era, writing one book a year is slacking. Name brand authors who once wrote one book a year are now writing two, and those who are sticking to a one-a-year schedule are also writing short stories and novellas to keep their names in view. To quote Lisa Scottoline from the NYT article, “the culture is a great big hungry maw, and you have to feed it.” And it’s not just name brand authors. Self-published authors are feeding the maw, too, sometimes with three or four or even six books a year.

Here’s an interesting dichotomy — there are so many books being published today that most will never sell more that 100 or 150 copies in a lifetime, yet an article in the New York Times says that in the e-reader era, writing one book a year is slacking. Name brand authors who once wrote one book a year are now writing two, and those who are sticking to a one-a-year schedule are also writing short stories and novellas to keep their names in view. To quote Lisa Scottoline from the NYT article, “the culture is a great big hungry maw, and you have to feed it.” And it’s not just name brand authors. Self-published authors are feeding the maw, too, sometimes with three or four or even six books a year.

Seems silly to me — authors scrambling to write extra books while many worthwhile books from small independent presses are going unread. There should be a way of evening things out, but people obviously prefer to stay with authors they are comfortable with. How else to explain the James Patterson phenomenon? Twelve books in twelve months? Yikes. Granted, some seem to be ghost written (or should I say guest written?), but still that is an incredible output considering that most people don’t read that many books in a year.

I’ve always loved books — in fact, as a child all I ever wanted when I grew up was time to lose myself in books — but now I’ve mostly lost my taste for reading. Too many books are shallow, even the well-written ones, and no wonder — authors who once had the time to write thoughtful books have to spend more time racking up the words and less time thinking. For me, a story isn’t enough. I want to be tantalized with insights, new ideas, different ways of viewing the world. I realize this is not the wave of the future. How deep can the ideas in a novel be if they are intended to be read on a phone or as an interactive ebook that’s enhanced with video, author interviews and social-networking applications?

I’ve never been one to follow the crowd. Sometimes I don’t even know where the crowd is. So it should come as no surprise that I don’t intend to increase my output of writing. (Though, come to think of it, any writing other than blogs would increase my output.) I couldn’t write more even if I wanted to. I am a slow writer. Even at my fastest, I can only write one book a year, and that doesn’t include editing and copyediting.

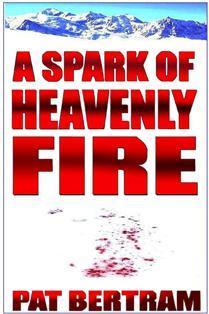

I am getting an interest in writing again, though. Sometimes I think about the books I’ve started and wonder what will happen to the characters, and just today I figured out how to develop my grieving woman book, the one I started for NaNoWriMo in 2010. It should be not so much a book about grief but about a woman’s journey into self-discovery, and so I should start the story before her husband dies, because it is during his long dying that she first loses herself.

This could be one of those books that takes a lifetime to write, since perhaps I will have to live the character’s life first. Or maybe I need to write the book as if I am writing my own future, and see what I can make of myself. Either way, the book would not be written in a month or even a year. It would take longer than that to glean the necessary insights.

According to the NYT article, “Publishers also believe that Salinger-like reclusiveness, which once created an aura of intrigue around an author, is not a viable option in the age of interconnectivity.” Luckily, I am neither self-published nor published by a major publisher, so I have the luxury of being as reclusive as I need to be in order to write whatever books might be in my future. (Shhh. It’s our secret. Don’t tell my publisher, Second Wind Publishing, I said that.)

Tagged: James Patterson, Lisa Scottoline, love of reading, New York Times, Salinger-like reclusiveness, writing more than one book a year

May 12, 2012

Getting Grief Right in Writing

Long before I knew the truth of grief and its power, I wrote A Spark of Heavenly Fire. The story begins thirteen months after the death of Kate Cummings’ husband, and she is still haunted by her small unkindnesses during his long illness. It surprises me that I got that part right because so much of the grief journey has been a shock to me, including how much I regret my own small undkindnesses toward my life mate/soul mate. I didn’t do anything bad, just lacked generosity of spirit at times during his last year. If he had lived, of course, these lapses would have passed unnoticed in the commotion of daily life, but with his death, they loomed like vultures over my spirit, waiting to tear me to shreds. If I had known how close to death he was, I would have been more patient, more understanding of his dying ways, but I didn’t know. I’ve come to realize that we were under such stress those last years that both of us did the best we could in the untenable situation. Dying is an unpleasant business for both parties.

Long before I knew the truth of grief and its power, I wrote A Spark of Heavenly Fire. The story begins thirteen months after the death of Kate Cummings’ husband, and she is still haunted by her small unkindnesses during his long illness. It surprises me that I got that part right because so much of the grief journey has been a shock to me, including how much I regret my own small undkindnesses toward my life mate/soul mate. I didn’t do anything bad, just lacked generosity of spirit at times during his last year. If he had lived, of course, these lapses would have passed unnoticed in the commotion of daily life, but with his death, they loomed like vultures over my spirit, waiting to tear me to shreds. If I had known how close to death he was, I would have been more patient, more understanding of his dying ways, but I didn’t know. I’ve come to realize that we were under such stress those last years that both of us did the best we could in the untenable situation. Dying is an unpleasant business for both parties.

Here are a couple of excerpts from A Spark of Heavenly Fire that show Kate’s torment. I wasn’t as feisty as Kate. I didn’t kick furniture or slam doors (well, maybe just once), and I didn’t give in to my anger until after he was dead, but otherwise, these passages show how much we bereft regret the small things we did:

Kate hauled herself upright and groped for her eyeglasses. After sitting on the edge of the bed for a moment, gathering her strength, she dressed and wandered through the house. She hesitated by the closed door of the second bedroom where her husband had lived during the last years of his protracted illness, touched the knob with her fingertips. Yanked her hand away.

This is ridiculous. Joe’s been gone for thirteen months.

Taking a deep breath, she grasped the knob, but could not force herself to turn it. She rested her forehead on the door for a minute, wondering if she’d ever be able to face the ghosts of sorrow and regret locked inside, then squared her shoulders and headed for the front closet to grab a coat and hat.

[Later in the book, Kate explains this inability to open the door to her new friend, journalist Greg Pullman.]

“A little over a year ago, during one of Joe’s rare remissions,” Kate said. “I mentioned we were coming up on our fifteenth wedding anniversary. When he ignored me, I asked, ‘Would it kill you to be nice to me once in a while?’

“He didn’t answer.

“I went out for a walk. When I returned, he was gone.”

“Dead?” Greg asked.

“No. Not then. He’d taken our car, an old Volvo, and left. I didn’t know he felt strong enough to drive. He could barely walk and had a hard time gripping so much as a glass of water.

“When the state patrol called to tell me Joe had been in an accident, that he’d driven off a cliff in the mountains and had died instantly, I wasn’t surprised. It did surprise me when they ruled it an accident. It seemed so obvious to me he’d taken his own life that I was sure everyone else could see it, too.”

Kate gave an unamused laugh. “I never did buy another car.”

Greg looked at her, a frown wrinkling his brow. “I don’t see that you did anything shameful.”

Kate toyed with her empty cup. “I’m not proud of what I said, and I hate knowing those were the last words I ever spoke to my husband, but I don’t think it had anything to do with his suicide. I doubt he even heard me.

“About two weeks after the funeral, I decided to clean Joe’s room. I didn’t feel up to sorting out his things, but I thought I should dust and vacuum in there. I cracked opened the door, as if expecting Joe, or at least his spirit, to inhabit the room. I stepped inside, but seconds later I scrambled out again and slammed the door.

“Memories of all the shameful, petty, inconsiderate things I had done over the years haunted the room, and I couldn’t bear to face my own mean spirit. Too many times I snapped at him or purposely waited a few minutes before going to see what he wanted when he called out. Other times I felt so angry at the way life had treated us, I stomped around the house, slamming doors and kicking furniture. Usually, though, I pounded my pillow, or cried. I’m embarrassed to admit how many times I cried, wishing I had a normal life with healthy children to take care of instead of an uncommunicative and disabled man. Sometimes I even hated him for what he had become, as if he chose to get sick. Can you believe that?”

She didn’t pause for a response, but hurried on, wanting to get it all out. “Worst of all, I realized I was not a strong woman who had shouldered her burden with courage, but a weak woman who lacked generosity of spirit.”

Greg reached across the table and put a hand over hers. “We are a sad pair, aren’t we?”

She gave him a wistful smile.

A full minute went by without either of them speaking, then she asked, “Would you like some more hot chocolate?”

Tagged: A Spark of Heavenly Fire, getting grief right, grief and regrets, grief journey, haunted by regrets

May 11, 2012

Where Do I Belong?

My favorite types of books have always been those where the character is out of place, as if she doesn’t belong in the world where she was plopped. By the end of the novel, of course, the character finds where she belongs — often with the one man who appreciates her — but we never hear the end of the character’s story. All stories end where life ends — in death. Authors simply pick the appropriate stopping place for the novel. So, as long as we imagine the character living happily ever after with her beloved, we know she belongs somewhere, but what happens to her when her beloved dies?

My favorite types of books have always been those where the character is out of place, as if she doesn’t belong in the world where she was plopped. By the end of the novel, of course, the character finds where she belongs — often with the one man who appreciates her — but we never hear the end of the character’s story. All stories end where life ends — in death. Authors simply pick the appropriate stopping place for the novel. So, as long as we imagine the character living happily ever after with her beloved, we know she belongs somewhere, but what happens to her when her beloved dies?

One short story I read when I was small affected me so much that I remember it all these decades later. (Though I don’t remember who the author was and, in fact, might not have known it. Back then, an author’s name was only important as a way of identifying the type of story, and I didn’t pay much attention to them otherwise.) The main character in the story was a young woman who had always felt out of place — the world and the people around her were alien to her. It turns out she was an alien stranded here on earth, and at the end, she was rescued and taken home.

It makes sense that such stories spoke to me since I too felt out of place. No matter how I tried to fit in, I never got it quite right, as if I were an alien trying to fit into a human situation. Then one day I stopped by a health food store, met the owner — a wise and radiant man — and all of a sudden the world made sense. If he was in the world, then the world wasn’t such an alien place after all. We never belonged to each other, but we did belong with each other. We thought alike, valued the same things, disvalued the same things. When he died two years ago, the world became alien once more, and I am back where I started, wondering where I belong.

As with many people in this mobile world, my parents left their hometowns, moved west, raised their family, then moved on again, which leaves me without a heritage, without a home. The place where I grew up has itself grown up — no longer a cow town but a world class city, and it is as alien to me as any city in the world. It didn’t matter as long as he was alive since he was my home, but now . . . where do I belong?

I’ve gotten over the hump of my grief. I am no longer in constant physical and emotional agony, though grief still stabs at me (sometimes several times a day), and I still have moments of panic when I remember that he’s not just gone out of my life but that he is dead. (That is still the worst aspect of this whole situation. I can deal with everything but his absence from Earth. How can he be so very gone? Where is he? Is he okay?) I am mostly back to being myself, though I’m not sure who I am, what I’m supposed to be doing, where I belong.

Right now, I’m taking care of my 95-year-old father, but this is not my home. In fact, I’d never even been here until my mother’s dying days. When my father is gone, the house will be sold, and I’ll have to find somewhere to live. But where do you go if you don’t belong anywhere?

Tagged: feeling like an alien, finding a home, grief and loss, out of place, stories that speak to us, where do I belong

May 10, 2012

Rules of the Writing Game

There are thousands of books on the market telliing us how to write the novel. Balancing those are Somerset Maugham’s oft-quoted adage, “There are three rules for writing the novel. Unfortunately no one knows what they are.”

There are thousands of books on the market telliing us how to write the novel. Balancing those are Somerset Maugham’s oft-quoted adage, “There are three rules for writing the novel. Unfortunately no one knows what they are.”

The truth is, we can change the rules of the game (assuming there are any rules). Why not? After all, it’s our game.We can do anything if we can make it work. But . . . if we want readers, we have to fulfill our side of the contract by fulfilling their expectations. If we write a boring story when we promised a thriller, if we don’t furnish a satisfying ending, if the book is riddled with typos and inconsistencies, then we have not fulfilled reader expectations.

In this anything goes publishing world, readers’ expectations seem at an all time low, otherwise why would they put up with the unedited, poorly constructed books that are downloaded every day by the hundreds of thousands? Still, most of us want more for our books than to be today’s free download fad. We want our books to have a life of their own, a life for which people are willing to pay a fair price. And for that, we need to know how to write, communicate, and tell a story.

Certain aspects of story telling never change — you need a beginning that hooks people, a middle that makes them want to keep reading, and an ending that satisfies. The writing has to be comprehensible. No reader wants to read the same sentence over and over again, trying to make sense of it. They want to find out what happens to the character. Which brings us to an important “must.” You must have a character who wants something desperately enough to drive the action of the story. Even if the character is unwilling to take action at the beginning, somewhere along the line she needs to take things into her own hands. A character who is unwilling to participant in her own story gets boring after awhile, and no matter how things change, that first commandment of writing will always hold true — though shalt not bore thy reader.

So, what are the rules of your game? What traditional rules do you follow? What rules do you make up? If you create your own rules, how do you make your story work?

Tagged: contract with readers, first commandment of writing, reader's expectations, rules for writing the novel

May 9, 2012

Do Us All a Favor and Let Your Characters Cry

Writers have a saying: if your character cries, your reader doesn’t. Writers seem to take this to mean that characters can never cry, that a tearful character is not a sypmathetic one, that readers cannot identify with a weeper. But tears are contagious — when watching a movie, I tend to cry if a character does. Still, even if the adage is true and readers don’t cry when a character does , is that so terrible?

Writers have a saying: if your character cries, your reader doesn’t. Writers seem to take this to mean that characters can never cry, that a tearful character is not a sypmathetic one, that readers cannot identify with a weeper. But tears are contagious — when watching a movie, I tend to cry if a character does. Still, even if the adage is true and readers don’t cry when a character does , is that so terrible?

As I mentioned in yesterday’s post, Why “Grief: The Great Yearning” is Important, I started writing about grief when I discovered that so many writers get it wrong. Many novels are steeped in death, with bodies piling up like cordwood, yet no one grieves. The surviving spouses think as clearly as they did before the death. They have no magical thinking, holding two disparate thoughts in their minds at once. (For example: I know he will never need his eyeglasses, but I can’t throw them away because how will he see without them?) The characters have no physical symptoms or bouts of tears that are beyond their control. There is no great yearning to see the dead once more (and this yearning is what drives our grief, not the so-called stages). In other words, we are continually conditioned to downplay the very real presence of grief in our lives. If we don’t see people grieve in real life, in movies, in books, where are we to get a blueprint for grief?

It’s simple enough to deal with the situation. Writers can let their bereft cry, and then later figure out a way to get the readers to cry. For example, if the character cries, is unable to staunch his tears, but later gathers himself together to deal dry-eyed with a story task, then the character’s strength and courage will have a heart-breaking quality about it. Or if the character deals with the task despite the tears running down his face, then that also is heartrending.

When my life mate/soul mate was dying in a hospice care center, I couldn’t stop the flow of tears, but I kept after the hospice workers until they made sure he was comfortable. (They screwed up his drug dosages, so he was in a massive amount of pain, and they wouldn’t give him the anti-nausea pill he needed because . . . why? I still don’t know. He was days away from death. What difference did it make?) They kept wanting to comfort me, kept wanting to ease my pain, but I told them every time, “Ignore the tears, they don’t mean anything. I have the rest of my life to grieve. Take care of him.” I couldn’t stop the tears, but, as I said, they didn’t mean anything (well, except that I was sad, in shock, and undergoing an incredible amount of stress). I still managed to do everything I had to do to keep him comfortable, and then later to deal with his funerary arrangements. The following two months, I had to dispose of his effects, clear out the house we’d lived in for twenty years, put my stuff in storage, travel 1000 miles so I could go take care of my 95-year-old father. During most of that time, I was crying (or screaming). Yikes, I never felt such pain and angst, and I hope I never do again. I can’t imagine how I ever survived those months. Yet I did. The point I’m making is that abstaining from tears does not make one heroic. What one does despite the tears — that is heroism. And such heroism will make your readers cry.

Another way writers can deal with a tearful character is to have a POV character overhear the hero sob, but when the character sees the hero a few minutes later, the hero is dry-faced, though perhaps with glistening eyes.

It’s not tears that readers don’t like — it’s self-pity. The surprising thing about grief is that very little of it (at least in the beginning) is self-pity. The questions and worries that beset the bereft are real and have to be dealt with. Ignoring the panic aspect of grief (that the world is forever altered, that there is a huge absence where once there was a presence) is a disservice to your characters and to your readers. You don’t have to let your character wallow — you can use their grief to catapult them to greater efforts. During those first two months when I had so much to accomplish (by myself, I might add), I used my periods of anger to fuel me. When the anger was overtaken by angst, I’d stop for a while.

And forget the “stages of grief” crap. There are no stages of grief, at least not for everyone. The absolutely worst fictional depiction of grief I ever read was “She went through all the stages of grief.” What does that mean? Simply that the author was lazy and didn’t do any research on what grief feels like. Having your character cry might not make your readers cry, but a silly sentence like that won’t make your readers feel anything.

In our society, we seem to believe that tears are a sign of weakness, when in fact they are a necessary stress release. The loss of a spouse is the most stressful thing a person will ever have to deal with. Tears release the hormones that build up in the system. If your protagonist’s loved one is not a major factor in the his/her life, you can get away with no tears, but please, if the loss is a major one, do us all a favor and the poor character cry.

Tagged: depicting grief in fiction, readers don't cry if a character does, sympathetic characters, why characters need to cry, writing about grief

May 8, 2012

Why “Grief: The Great Yearning” is Important

Yesterday I was on Blog Talk Radio discussing my new non-fiction book Grief: The Great Yearning and explaining why it is important.

Yesterday I was on Blog Talk Radio discussing my new non-fiction book Grief: The Great Yearning and explaining why it is important.

I’ve written four novels, all published by Second Wind Publishing, and although I thought the subject matter of each book important enough to spend a year of my life writing and another year editing (to say nothing of the years on the arduous road to publication), I have a hard time telling people the novels are important.

The basic theme of all my novels is conspiracy, focusing on the horrors ordinary citizens have been subjected to by those in power. Most people who have read the books seem to like them (though a few who didn’t like them seemed befuddled by what I was trying to accomplish). Light Bringer in particular seems to arouse a difference of opinion. Written to be the granddaddy of all conspiracy theories, Light Bringer traces the push toward a one-world government back 12,000 years. Based on myths, both modern conspiracy myths and ancient cosmology myths, Light Bringer is a thriller, or mythic fiction perhaps (if there is such a thing). I never intended it to be science fiction since the science is gleaned from ancient records rather than futuristic imaginings, but that is how it is perceived. Still, despite the scope of the book, despite it being my magnum opus and the result of twenty years of research, I can’t in all honesty say it is important to anyone except me. It probably won’t change anyone’s life or anyone’s thinking. For the most part, we bring to books what we believe, and so those who believe in conspiracies see the importance of my novels, while those who don’t have even a smattering of belief that there are machinations we are not privy to might even think them far-fetched.

On the other hand, Grief: The Great Yearning is an important book. It is composed of journal entries, blog posts, and letters to my dead life mate/soul mate, all pieces written while I was trying to deal with the unbearable tsunami of emotions, hormones, physical symptoms, psychological and spiritual torments, identity crisis and the thousand other occurrences we lump under the heading “grief.” Because of this, the emotion in Grief: The Great Yearing is immediate, the experience palpable. This is a comfort to those having to deal with a grievous loss because they can see they are not alone. (One of the side effects of grief is a horrendous feeling of isolation.) They can see that whatever they feel, others have felt, and that whatever seemingly crazy thing they do to bring themselves comfort, others have done.

This book is also important for the families of someone who has suffered a grievous loss. Too often the bereft are told to move on, get over it, perhaps because their families don’t understand what it is the survivor has to deal with. Well, now they can get a glimpse into grief and ideally, be more patient and considerate of their bereft loved ones.

This book is especially important for writers. I’ve mostly given up reading for now because of the unrealness I keep coming across in fiction. So many novels are steeped in death, with bodies piling up like cordwood, yet no one grieves. The surviving spouses think as clearly as they did before the death. They have no magical thinking, holding two disparate thoughts in their minds at once. (For example: I know he will never need his eyeglasses, but I can’t throw them away because how will he see without them?) The characters have no physical symptoms or bouts of tears that are beyond their control. There is no great yearning to see the dead once more (and this yearning is what drives our grief, not the so-called stages). In other words, we are continually conditioned to downplay the very real presence of grief in our lives. If we don’t see people grieve in real life, in movies, in books, where are we to get a blueprint for grief?

As Leesa Healy, Consultant in Emotional-Mental Health wrote, “If people were to ask me for an example of how grief can be faced in order for the healthiest outcome, I would refer them to Grief: The Great Yearning, which should be the grief process bible. Pat Bertram’s willingness to confront grief head on combined with her openness to change is the epitome of good mental health.”

So, yes, Grief the Great Yearning is important, and it was good to have a chance to talk about the book and to spread my message: It is okay to grieve. It is important to grieve. And as impossible as it is to imagine now, you will survive.

If you’d like to listen to me talk (and laugh) and discover that I really am okay despite my continued sadness and occasional upsurges of grief, you can find the show here: Talk Radio Network with Friend and Author Pat Bertram

Click here to find out more about Grief: The Great Yearning

Tagged: blog talk radio, Grief: The Great Yearning, important book about grief, interview with Pat Bertram, mythic fiction, talking about grief

May 7, 2012

I am going to be on blog talk radio today!

I am going to be on blog talk radio today speaking to Jo-Anne Vandermeulen. Or should I say, she will be speaking to me? Either way, we will be discussing my new book, Grief: The Great Yearning, why I wrote it, and why the book is important. If time allows, we’ll also talk about how I help other writers and perhaps we might touch on more general topics, such as the future of books. (Jo-Anne wanted a list of ten topics for us to discuss. I guess she didn’t realize I could talk for hours about grief and its unwelcome role in our lives.)

I am going to be on blog talk radio today speaking to Jo-Anne Vandermeulen. Or should I say, she will be speaking to me? Either way, we will be discussing my new book, Grief: The Great Yearning, why I wrote it, and why the book is important. If time allows, we’ll also talk about how I help other writers and perhaps we might touch on more general topics, such as the future of books. (Jo-Anne wanted a list of ten topics for us to discuss. I guess she didn’t realize I could talk for hours about grief and its unwelcome role in our lives.)

The show is a half an hour, from 6:30pm ET to 7:00pm ET (3:30pm PT to 4:00pm PT). I hope you will tune in to listen, but if you can’t, well . . . blogs are forever, and blog talk is no different. The show will be available whenever you get a chance to check it out. It should be a good show. Not only is 30 minutes a manageable block of time, there will only be one guest (me!) and one host, so it should be a dynamic show. And anyway, you’ve been wanting to hear what I sound like, so here is your chance!

Link to show: Talk Radio Network with Friend and Author Pat Bertram

Guest call-in number: (347) 857-3752

Tagged: blog talk radio, interview, Jo-Anne Vandermeulen, Talk Radio Network, talking about grief

May 6, 2012

How are characters integral to the setting?

I often troll my site statistics, curious as to how people found this blog, and the other day, several people landed here after Googling “How are characters integral to the setting?” It sounds like they were taking the easy way out doing their homework, but still, it’s a very good question. If the setting is simply a place for events to unfold, then the author has missed out on an opportunity to tighten the story by making the characters an integral part of the setting and the setting an integral part of characterization. Everything should be in service to the story, including the setting.

I often troll my site statistics, curious as to how people found this blog, and the other day, several people landed here after Googling “How are characters integral to the setting?” It sounds like they were taking the easy way out doing their homework, but still, it’s a very good question. If the setting is simply a place for events to unfold, then the author has missed out on an opportunity to tighten the story by making the characters an integral part of the setting and the setting an integral part of characterization. Everything should be in service to the story, including the setting.

In my novel, A Spark of Heavenly Fire, the setting and characters are intertwined. The setting is Colorado in the midst of an epidemic. The story is driven by the women, all very ordinary, especially Kate. And that was the point — to tell a story of an ordinary woman who struggled during prosperous times when everyone else was doing well, but who managed to prosper in the dark times when everyone else was having difficulties. Without the epidemic, without the quarantine, without the very terrain of Colorado, Kate would have no being. And without Kate and the other characters, the setting would have no meaning.

Eudora Welty said, “Every story would be another story, and unrecognizable if it took up its characters and plot and happened somewhere else.” Most of my books are set in mountain climes, and the mountains create the characters and the characters complete the setting. A stage is empty and lifeless without the characters. You need characters to interact with the setting to make it come alive.

Think of a desolate area, such as a desert road. It evokes a feeling of loneliness, but if you put a character on that road, you personify the loneliness.

The setting/character relationship is not simply a story construct. We are integral to our settings and vice versa. Gardening and lawn care is one very obvious way we are integral to our settings. If not for gardeners, gardens would not exist. But the settings of our lives extend beyond such evident comparisons.

I used to live off a highway on a dead end road bounded by fenced alfalfa fields, so the only place I could walk was by trudging up and down that .3 mile road. This was indicative of my life at the time. My life mate/soul mate was dying, had been dying for a long time, we were stuck in a terribe situation that seemed to be going nowhere.

He is gone out of my life now, and so are the interminable laps on the short road. I left that place of constraints and came to this desert community to take care of my 95-year-old father. When I first got here, I walked the long straight roads in the nearby desert. They seemed indicative of my new life — emptiness and desolation and loneliness stretching endlessly before me. More recently, I’ve taken to hiking a narrow path up and over the knolls. This too is indicative of my life. The desolation isn’t as pronounced, but the challenges are becoming greater as it sinks it that I will always live with his absence, that I will be growing old alone. The true challenge, though, is to make room for joy along with the continued sadness.

I’ve come to see that this is the true purpose of grief — to stretch our minds, souls, psyches so that we can encompass all that life has to offer. At first I thought I could get over my grief. Then I thought I could bury it with new activities. Now I see that sorrow will always be a part of me, but that doesn’t mean it will be the only part of me. Nor will I always be here in the desert. There will be new places to walk, places that reflect the changing me at the same time as I reflect the places.

How are your characters (or you) integral to the setting?

Tagged: blog statistics, characters and setting, desert walk, Eudora Welty, grief and loss, purpose of grief

May 5, 2012

“Golly gee what have you done to me?”

As part of my quest to refigure the pathways in my mind and open myself up to more light, I’ve been doing my version of dance therapy — dancing to a peppy song or two every day. I hop a bit, wave my arms around, and surrender to the rhythm. It generally works to lighten my mood, but today, Saturday, my sadder day, the song had the opposite effect and I ended up pummeling the air instead of bopping to the beat.

The song? Buddy Holly’s “It Doesn’t Matter Any More.”

Cripes. As if I really needed to hear Buddy singing, “There you go and baby here am I / Well you left me here so I could sit and cry / Golly gee what have you done to me?”

Someone told me that grief over the death of a mate is like a relationship gone bad, and sometimes it does feel that way. I talk to him, and he says nothing in return. I beg for a hug, and he ignores me. I yearn for him, and he remains remote. I ask what happened to us, what did I do that was so terrible he had to leave me, and he doesn’t answer.

And then I remember — he didn’t leave me, he died. Now he is there and I am here with no way to bridge the gap. We don’t even have the opportunity to get together to fight about who gets what — I ended up with everything by default. If he were here, he could have everything. I’d even let him have the silly dishes we argued about that last year. (I received a set of Melmac dishes for Christmas when I was young. It was some sort of giveaway, and my mother got the whole set and saved them for my hope chest — though it wasn’t a chest, just a shelf in the kitchen cabinet. I still use those dishes occasionally — they are a wonderful size, and so very light.)

He and I shared everything during our years together, but for some reason I got very protective of those vintage dishes the last year of his dying. We’d started cutting up beets and other colorful vegetables for salads and I asked him not to use those plates — they were white and the beet juice stained them — but he kept using them anyway. (I should have known something was dreadfully wrong with him — he was the most considerate person I’d ever met.) I don’t know why my frustration over his continued decline focused on those dishes, but it did. I don’t even know why it mattered. It sure doesn’t matter any more.

The song (“It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” written by Paul Anka) continues, “Now you go your way baby and I’ll go mine / Now and forever till the end of time.” Yeah. A real spirit lightener.

The song ends with the words, “baby / We’ll say we’re through / And you won’t matter any more.”

We might be through — my life mate and I — and I wish I could say he doesn’t matter any more, but he does. And he always will.

Tagged: Buddy Holly, grief and death, grief and loss, grief is like a bad relationship, It Doesn’t Matter Any More, melmac dishes