Gerald Everett Jones's Blog: Gerald Everett Jones - Author, page 29

August 13, 2023

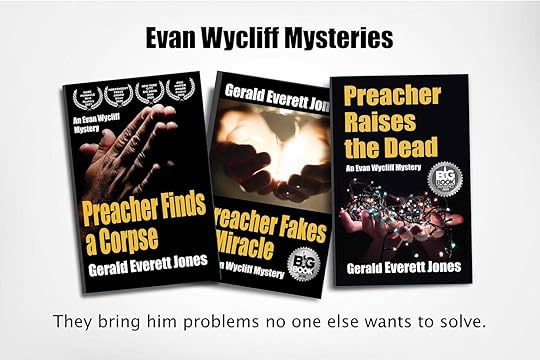

Preacher Stalls the Second Coming

Follow this blog for excerpts and release date and…Prepare.

Follow this blog for excerpts and release date and…Prepare.Read all three prequels - available in ebook and paper from booksellers worldwide.

Preacher Finds a Corpse, the first ebook in the award-winning series is free from most distributors.

Kindle on Amazon. EPUB Apple Books, Kobo, and others

Thinking About Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

August 9, 2023

Unimaginably big does not begin to describe...

A new episode of The Unknown documentary series on Netflix describes the technical challenge of, and the stunning results from, the James Webb Telescope. Besides its significance in the history of science, perhaps the most breathtaking takeaway is at the level of society and geopolitics. The NASA Next-Generation Space Telescope (NGST, a joint mega-project with Europe and Canada) is the most complex space mission ever attempted, many times more complex than the Moon landings. The work effort took more than 30 years and employed more than 10,000 team members. In the film, project scientist Thomas Zurbuchen comments that not only did he have panics of doubt during the project, it was fraught (as human efforts will be) with team disagreements, personnel issues, never-attempted and just unlucky engineering challenges, and interruptions of its $10B funding. His point being—not just what a wonderful technical achievement it is—but that if a [government-sponsored] effort of this difficulty can succeed (as it has), we [people acting in groups] should be able to solve anything.

The telescope is now “parked” a million miles from Earth at a stable LaGrange point. That’s a place where the gravitational pull from surrounding bodies is relatively balanced. The satellite therefore should be able to remain there with minimal fuel expenditure for repositioning. Duration of the mission is expected to be at least 5-10 years.

Unknown: Cosmic Time Machine (Netflix) link to the episode

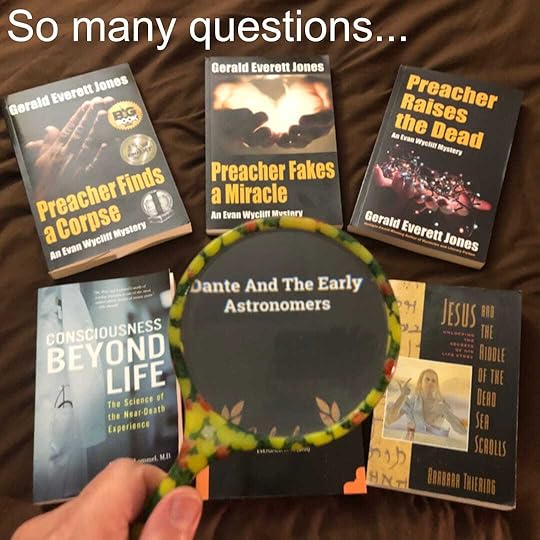

Webb’s infrared image of the galaxy cluster El Gordo (“the Fat One”) reveals hundreds of galaxies, some never before seen at this level of detail. El Gordo acts as a gravitational lens, distorting and magnifying the light from distant background galaxies. Two of the most prominent features in the image include the Thin One, located just below and left of the image center, and the Fishhook, a red swoosh at upper right. Both are lensed background galaxies. (NASA STSci)

Stunning to me, as much as I’ve studied astronomy as a layman, “beyond imagining” doesn’t begin to describe the size of the universe. In one of the film’s insider scenes, NASA officials are looking at a poster-sized print of an early deep-space photo from the telescope. NASA Director Bill Nelson is preparing to present it to President Biden, who will show the image to a national audience. Nelson wants to know how he should describe the picture to the President. A project scientist answers that most of the bright specks on the black field aren’t stars—they’re entire galaxies. In that shot, there were about 7,000 of them. Then he adds—the relative size of that image compared to the whole sky is a grain of sand!

I have serious, educated friends who are nevertheless literalist Bible scholars. They insist Earth is the only place where God’s creatures exist. I doubt whether that belief will survive the next generation, among any of us.

I have my grandmother’s set of The Standard American Encyclopedia, copyright 1937. Turning to the entry “Universe” in Volume 13 TER-UZH, I read that “the diameter of the known universe is 600 million light years,” containing 75 million galaxies. I was actually surprised that a book of this vintage would describe a cosmos that large. When I was in elementary school in the 1950s, our teachers talked about the solar system and a few stars beyond.

In the generation of Webb, the size of the universe is estimated at 28 billion light years with 2 trillion galaxies.

The age of the universe has been calculated at 13.8 billion years since the Big Bang. The Webb telescope should be able to “see” the formation of stars at 13+ billion light-years away—baby snapshots, you might say.

Past that distance, presumably no device will ever be able to see anything. That’s the event horizon.

The light from objects out there has not had time to reach us yet!

Until August 14 from ebook distributors worldwide, Kindle and EPUB.

August 6, 2023

No Such Thing As Eternity?

Here’s my book review of Until the End of Time by astrophysicist Brian Greene. Until now, I thought eternity was a thing.

If there’s no superintelligence to think, how could it start over?

It’s the best survey of current theories in cosmology that I’ve read. But it’s also the most unsettling to someone like me who tries continually to reconcile science and theology.

Fans of my Evan Wycliff Mystery series know that Evan is similarly conflicted. A farm boy from southern Missouri from a devout Baptist family, he thought he’d go into the ministry. But then he studied at Harvard Divinity, where learning more about the history of Christianity and its hypocrisies shook his faith. Then, seeking answers to the big questions instead in science, he enrolled in postgrad astrophysics at MIT. He dropped out of that program, too. Discouraged and heartbroken for other personal reasons, Evan returned to farmland roots, where he got occasional work as a guest preacher and a credit investigator for the local car dealer.

Evan is a preacher who some days is an agnostic. And he’s an amateur sleuth because he has investigative skills. People in his community come to him with problems that no one else has any interest in solving.

So – no surprise – from the standpoint of intellectual curiosity, Evan and I are a lot alike.

Two conclusions in Greene’s book would startle us both. First, there can be no such thing as eternity. The universe is about 14 billion years old and has more than double that time before it expires. But, according to Greene, expire it will – expanding and disintegrating into cosmic dust, then expanding more until particles are so far apart they can’t form any solid mass – no galaxies, no stars, no planets.

Now, from the viewpoint of the philosopher or mystic, eternity is not simply a long, long time. Or even a timeline that has no end. It’s a state of being. Time-less – an incomprehensible notion for the human mind.

But more disturbing still is Greene’s assertion that – long before the universe expires – thought itself won’t be possible. Thought in humans is biochemically supported electrical activity in the brain. When the cosmos becomes diffuse, no such complex structures will exist.

Now, unaddressed in Greene’s survey is the question of whether consciousness and thought are aspects of the same physical process. Some scientists, including Christoph Koch, have tried to explain consciousness as super-complex electrical activity in the brain. Koch has found no such explanation. He theorizes that computers, no matter how complex, can never be conscious. In his book The Feeling of Life Itself, at the conclusion he can only guess that consciousness is some as yet unmeasurable, fundamental property of the universe, a feeling shared by all living things, in various degrees depending on the complexity of their brains. For rigorous scientist Koch, it’s little more than a guess.

Where is God in all this? Our religious traditions hold that God is pervasive consciousness and eternal. Another hypothesis of Greene and his colleagues is the so-called godless universe. That is, the dual processes of entropy (diffusion) and evolution (ever-increasing complexity) are sufficient to explain everything that exists.

Which brings us to the most elusive question of all, one that philosophers have debated for centuries, which also has the scientists stumped:

Why is there something rather than nothing?

Did you get the memo? First ebook in the series free, the other two 99c until August 14. (Kindle or EPUB)

August 2, 2023

Where are you going on vacation?

I have a lot of respect for Michel Houellebecq as one of today’s foremost practitioners of literary fiction. I’d put Paul Auster in that category, as well. I’ve reviewed other novels by both of them in this blog. Another reason to read Platform was that its premise seemed comparable to my Harry Harambee’s Kenyan Sundowner – that is, an older, single, middle-class white man sets off on a vacation to an exotic resort where he expects he will find hookups and parties.

There the similarity mostly ends. Platform’s protagonist, Michel Renault, is in his mid-forties. Harry Gardner is at least twenty years older. Both are men of comfortable means with time on their hands. Michel travels to Thailand, Gardner to the south coast of Kenya. Both places are widely known to provide the kinds of recreation these men seek.

July 30, 2023

Here's My Take on 'The Idol' (Max Series)

The routine meetings at a major Hollywood packaging agency are typically about building the star’s brand - as manifested in her artistic genre and style, makeup and hair, couture - and especially her public persona. The persona is a crafted thing, a product identity, and may be no closer to the star’s private personality than The Joker is to Joaquin Phoenix (whose private life these days is said to be more about wildlife conservation and veganism).

Be cautioned, but only if you’re squeamish about such things. The Idol includes incidents of brutality, rape, and torture. Although celebrity life stories have at times included all kinds of bad behavior, I’d suggest that the daily business of show business is often downright-dull business.

Thinking About Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Much of the time, these celebrity-management discussions are no more interesting than it would be to decide on a new product label for a bottle of ketchup.

But the products of showbiz must never be boring to their consumers. So a fictionalized insiders’ look at the biz must have the volume control on excitement turned way up.

There’s also—no surprise—lots of skin, mostly the star’s.

The title role of this recent streaming series on Max refers to the rising, twentysomething pop-music star Jocelyn (Lily-Rose Depp). In this story, her previously stunning singing career could quickly tank after a traumatic episode in her personal life has made her cancel a stadium concert and a roadshow. She’s debilitated by the death of her overbearing stage mother and a consequent crisis of confidence.

Into her life comes Tedros (Abel “The Weeknd” Tesfaye), a sleazy nightclub owner with a hustler rap sheet whose own self-confidence is off the charts. He fancies himself a star-maker, and he’s surrounded himself with a posse of truly talented, hungry-wannabe performers, who seem to be both his drug clients and his sex slaves.

So it would seem the stage is being set for an updated Trilby-seduced by-Svengali plot (or Christine and the Phantom). However, the first episode hints at an older, darker archetype. When Jocelyn is being interviewed about her comeback by a reporter from Vanity Fair, the reporter admits that her editor is pressuring her to emphasize a recent scandalous incident. The star shrugs that we must all answer to someone. Which makes the reporter ask whether Jocelyn thinks she’s accountable to anyone. After a moment’s hesitation, she answers, “To God.”

Now it seems the star might secretly have a Bible under her pillow. In a later scene, in the gloom after sundown, the huge electric gate at Jocelyn’s estate opens slowly to reveal the eerily backlit figure of Tedros, dressed in a long, black frock coat, striding menacingly toward us.

The imagery suggests the model for Tedros is not Svengali—but Satan—come to claim Jocelyn’s soul. She is to be, therefore, a latter-day Faust. The Evil One will make her an earthly god—then destroy her in the afterlife.

[Spoilers follow…]

But this exalted theme does not play out—at least, not in the five episodes of Season One. Tedros does indeed coax her to perform with more passion and virtuosity. As she reaches a new level of artistry, we assume she has become his slave in exchange. She is obviously his willing partner in intimacy. He seems brutal, but we can tell she likes it rough.

Then, twist upon twist, and all in Episode Five: She dumps Tedros, marches onto the concert stage at the 70,000-seat SoFi Stadium, and then—deus-ex-machina in reverse—she publicly takes him back. She has the power now. Professionally, at least, her evil master has become her slave.

Reviews of the series have been mixed, many of them negative. Admittedly, the story is dotted with gaps in logic. Jocelyn’s character at first seems weak-willed and easily manipulated, then it’s suggested she’s been playing Tedros all along, for which there is almost no setup. On the contrary, throughout the first four episodes, her managers and backers seem to be jerking her around, fine-tuning her branding and continually repositioning her for maximum consumer appeal and commercial success. Eventually, those pros think they’ve outfoxed Tedros, then, just before fadeout, we’re made to think Jocelyn has prevailed against them all.

In the end, in fiction as well as in the real business of show business, anyone who can sell out stadiums and hit the top of the charts with her albums will get everything her own way.

But will she answer to God?

Yes, at least in her speech when she holds a Grammy.

FREE Kindle ebook today (July 30, 2023) on Amazon.

My romantic comedy Mick & Moira & Brad tells the story of an ambitious young woman’s rise to stardom, but there the similarity to The Idol ends.

Click the player to hear me read the first chapter of Mick & Moira & Brad.

Thinking About Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 28, 2023

My Teatime with Miss Liz

Miss Liz thinks the Great Reset is coming! (Hmm, I think I hit the Fast Forward button my mistake…)

What are the consequences of pretending to be someone you’re not? #MeThree

July 27, 2023

Summer eBook Meltdown - Makes Little Cents!

Free - first book in each seriesStay cool. Be curious. Keep one step ahead of the bots. Relax and read!

My Inflatable Friend (Misadventures of Rollo Hemphill #1)

Preacher Finds a Corpse (Evan Wycliff Mysteries #1)

99¢ - a penny less than a buck for a limited timeRubber Babes (Misadventures of Rollo Hemphill #2)

Farnsworth’s Revenge (Misadventures of Rollo Hemphill #3)

Preacher Fakes a Miracle (Evan Wycliff Mysteries #2)

Preacher Raises the Deat (Evan Wycliff Mysteries #3)

Mr. Ballpoint (Comic Novel)

Christmas Karma (Comic Novel)

Choke Hold (Elif Wolff Thriller #1)

Bonfire of the Vanderbilts (Historical Novel)

Clifford’s Spiral (Literary Fiction)

Harry Harambee’s Kenyan Sundowner (Literary Fiction)

The Death of Hypatia and the End of Fate (Historical Essay)

Boychik Lit (Stories)

White-Collar Migrant Worker: Making Your Way in the Gig Economy (Business)

How Not to Abuse Metadata (Business)

11 Ways to Spot Fake News (Business)

Reduced to $2.99 (Kindle only - not available in EPUB)How to Lie with Charts (4th Edition)

The Misadventures of Rollo Hemphill (Compilation)

One of us approved this message.

Paperbacks and audiobooks still available but not marked down.

July 26, 2023

1954 Novel Tells Consequences of VR

That’s the subtitle of Shepherd Mead‘s 1954 novel, The Big Ball of Wax.

Do you wonder – perhaps with trepidation and creeping anxiety – what the socioeconomic impacts of Virtual Reality (VR) might be?

The Big Ball of Wax: A Novel of Tomorrow’s Happy World by Shepherd Mead. Here’s the cover of the Ballantine Books mass-market paperback I read back in the day. It’s now available on Kindle.

Well, author Mead did that with painful humor back in 1954, before the maestro of Meta was even an embryo. Now that some are betting the high-tech farm on VR, perhaps we’d do well to take another look at this crusty tale.

July 23, 2023

What are you trying to say, Claude Monet?

By that time, he was prosperous enough to buy a farm estate at Giverny, located a train-ride trip from Paris. Here’s a picture of him in his eighties, seated on a bench near the pond on the estate where he painted his masterwork series of water-lily panoramas.

I don’t think he ever retired. But he did put on a new suit when the photographer came to visit him at his country estate. The suit, the hat, and the boots look new, his beard freshly barbered. He’s about to say something. What is it he wants to tell you?

I first saw this photo in the gift shop at Giverny. It’s a wall-sized blowup. I see him all dressed up in his three-piece suit – very probably, his best – waiting for the photographer. He has a straw hat to shade his eyes. He usually wore one with his bib overalls and old long-sleeved shirt when he painted. Perhaps this is a new one. You can almost see the gold-rimmed spectacles staring out beneath the brim. And the long beard was a trademark, dating from back in the day when it wasn’t all white.

Thinking About Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I could imagine his saying to me, “Well, let’s get on with it.” Or, “What are you waiting for?”

I have a framed copy of it on the wall in my bathroom.

He asks me those questions every morning.

Here’s how he saw the pond behind him in the photo.

And what do you think this guy wants to say?

Thinking About Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 19, 2023

Show Don't Tell - Or Maybe Not Always

You may have noticed that I live on the Left Coast, in a region some might call “Hollywood adjacent.” Understand that, particularly for LA-based writers, the brass rings for commercial success dangle from buyers in the entertainment business. Note the term. They don’t say cultural-arts or literary edification business. Neither of those high-brow terms would suggest carnivals or striptease, but entertainment can and does imply amusement rather than art as its emphasis.

Stop me before I rant again. The misuse of the term entertainment is not the essence of my rant.

I feel strongly that show-don’t-tell advice is and should be a hard-and-fast rule for screenwriters. But novelists can and should safely ignore such preaching. Consider the scene description:

EXT. STRIP CLUB ENTRANCE - NIGHT

MALCOMB, a callow youth (19), gazes at the marquee. He’s never been inside such a place. His mother told him to stay away.

As scene description, only the first sentence is specific enough visually to suggest to the actor, director, and crew how to shoot the scene. The next two sentences might well go in a novel, but have no place in a script. He’s never been inside such a place commits the screenwriter’s sin of coaching the actor. The writer might instead visualize: The character hesitates, scratches his head, or becomes short of breath from a panic attack. The actor will interpret.

There is no way for Malcolm to show in this scene that his mother ever warned him away from such behavior.

So, point taken. Screenwriters should show. Always.

Oops, there is an exception to this rule, one that in recent years filmmakers frowned upon—use of voiceover dialogue to tell the audience what a character is thinking. This practice, like murky inferences in scene descriptions, was thought to be a cheat, betraying the screenwriter’s lack of visualization skill.

The writing coach’s advice instead of VO typically is to bring on another character so the exposition can be given in dialogue. The distressed character is still telling, but at least the audience gets to watch a conversation (or more dramatically, an argument).

However, VO is commonplace these days, particularly by alienated characters who have no friends to confide in or whose thoughts are so dark they dare not utter them.

Literary agents who represent screenwriters aren’t selling literature. In today’s publishing marketplace—except for rare bestsellers—agents make big money not from their percentage of book advances but primarily by selling the movie rights.

They will engage in their show-don’t-tell speeches with the rationale that latter-day readers of novels are more like movie audiences. Readers today, these gurus might advise, want to see it all, even in prose.

To novelists I will say, this is misdirected advice. Agents want stories that are easily adaptable to the screen. This preference and the reasons for it should not be a surprise.

Making all fiction literature read (and be structured) like screenplays impoverishes the range of literary expression. In a novel, the writer should not exclude any useful trick of the trade. What about voiceover (aka interior monologue)? Stendhal introduced it in “modern” fiction—in 1814.

Showing? Yes, please. Blow-by-blow, and in real-time. (Don’t overdo the adverbs, another potentially contentious thou-shalt-not.)

But telling? Don’t give us long descriptions of episodic travel except when the travel itself is the story. Don’t waste pages recounting the passage of time unless whatever happened during those years advances the plot. Novelists can use telling to summarize and condense, to traverse space and compress time.

And then there are the omniscient narrators—be they in the first or the third persons—who enthrall us by using the “storytelling” voice around a campfire on a starlit night:

Listen, my children, and you shall hear…

When I attended a panel discussion at a literary event not long ago, I rose to my feet and dared to ask renowned novelist and screenwriter Michael Tolkin whether a novelist should follow the advice of showing and not telling.

His glaring look told me I was nuts and should sit the f*k back down.

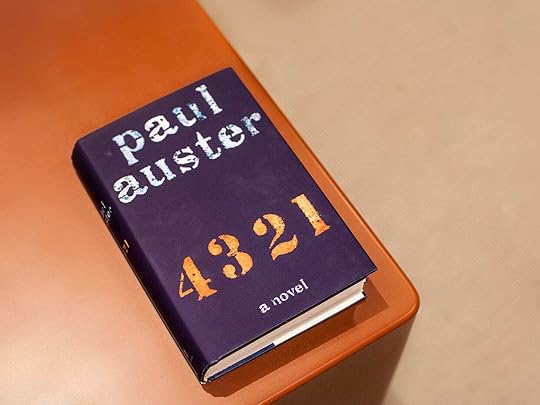

Paul Auster’s family-saga novel 4 3 2 1 is boldly all tell, no show. (Your book coach will advise you not to try this at home.)

But I have better evidence to offer: Consider the novel 4 3 2 1 by Paul Auster. This lengthy family saga is all telling—a hundred percent. There is not one line of dialogue nor any event described as if the action occurs in the present moment.

So, is 4 3 2 1 a fundamentally flawed work? The judges of the Booker Prize must not have thought so—they short-listed it for the award.

As for Auster, I haven’t read all of his novels, but enough that I know he makes it a rule to break the rules.

Maybe he wrote this one just to flip off some editor who scolded him, “Show! Don’t tell!”

There’s some show, some tell. Show when it’s real-time and exciting. Tell when if you didn’t summarize it would be a snore. Start the story here.