Y.S. Lee's Blog, page 18

October 30, 2013

Monkey business

Hello, friends. I was never a huge fan of Hallowe’en – until I had small children to dress in funny costumes, of course. And this year I’ve really lucked out: both children (ages 5 and 2) are going to be monkeys. Or, as the two-year-old insists, “cheeky monkeys!”

Surprisingly, it didn’t take any cajoling on my part. They had free choice, and then I zipped them out to Value Village before they could change their minds. I spent a couple of evenings making monkey ears, a pair of needle-felted bananas, and curly tails. And here we are.

Happy Hallowe’en, everyone! What are you going to be?

October 23, 2013

Kingston Penitentiary, Part 1

Hello, friends. A few days ago I finally fulfilled, with thanks to my friend Michelle Gibson, a longstanding ambition to snoop around Kingston Penitentiary! (I requested a tour on my own, many years ago, but Corrections Canada is not interested in accommodating the curiosity of local residents – even if we are Professionally Nosy, aka writers.) But the Penitentiary was recently closed for good and the United Way of Kingston is cleverly fundraising by offering a limited number of tours. I turned up on a brilliant autumn day and met our volunteer tour guide, a retired guard named David Stewart.

The oldest parts of the Penitentiary were constructed in 1835 and walking through the front door is a deeply Victorian experience. It’s high and dark, and you are made to feel very small. You snake through a corridor and emerge in the Visitation and Correspondence (V&C) room. It’s a deeply dispiriting space: low-ceilinged, dingy and windowless, with glass-topped tables and fixed seats. The saddest part of the room is the children’s corner, which someone has attempted to make more cheerful with a little bright paint. It still contains a couple of strollers and a handful of toys, and there remains a poster on the wall reminding you that Loving Fathers Read to Their Children. I’ve seldom seen a space that so makes me despair of lost potential.

Our guide, Dave, mentioned that there were hidden microphones in each table, so that guards could monitor conversations between inmates and their visitors. KP was used as a maximum-security institution so there was also a visitation area where inmates were separated from their visitors by a glass partition and talked to them via telephone, as I’m sure you’ve seen in the movies.

We followed Dave outside, squinting in the sudden sunshine, and this was the first thing I saw.

More heartbreak. There are six of these “family units” for inmates who earned visitation privileges through good behaviour. For 72 hours at a time, their families could come to stay with them in one of these houses. There, they could cook their own food and generally try to fabricate a domestic life.

More heartbreak. There are six of these “family units” for inmates who earned visitation privileges through good behaviour. For 72 hours at a time, their families could come to stay with them in one of these houses. There, they could cook their own food and generally try to fabricate a domestic life.

We walked past the family units and there was sudden murmur of admiration:

This is the North Gate, through which vehicles holding prisoners were originally admitted. The belltower at the top had an important function in the nineteenth century. According to Dave, all prison employees had to live within earshot of the bell. If there was an emergency, someone would ring the bell and everyone had to muster at the Pen to pitch in. Despite the context, isn’t that gate beautiful?

This is the North Gate, through which vehicles holding prisoners were originally admitted. The belltower at the top had an important function in the nineteenth century. According to Dave, all prison employees had to live within earshot of the bell. If there was an emergency, someone would ring the bell and everyone had to muster at the Pen to pitch in. Despite the context, isn’t that gate beautiful?

The barred windows below are on one arm of the Pen’s cross-shaped central building. They allow some light and ventilation into the ranges (rows of cells), and were cleaned by inmates. Inmates also cleared snow, gardened, cooked, did laundry, and many other tasks on the premises.

All that sounds quite orderly, if not downright cozy. Then you walk inside to view a typical range:

All that sounds quite orderly, if not downright cozy. Then you walk inside to view a typical range:

All the cells are singles, but the “typical” ones are arranged in rows of about ten. If you lived in one, you’d be able to hear and smell your neighbours – unless, of course, you were atypical. Inmates who couldn’t be in the company of others – especially the notorious – were held in isolation cells, which we didn’t view.

All the cells are singles, but the “typical” ones are arranged in rows of about ten. If you lived in one, you’d be able to hear and smell your neighbours – unless, of course, you were atypical. Inmates who couldn’t be in the company of others – especially the notorious – were held in isolation cells, which we didn’t view.

Inmates in insolation cells remained there for 23 hours a day. During the one hour they were permitted outside, they used one of a few small “yards”, where they were again alone. We didn’t view these yards but I grabbed a shot through a dirty window.

One of the doors to such a yard had a small trapdoor just below waist height. Dave explained that a particularly aggressive or dangerous inmate would be led outside in handcuffs. Once outside, the guard would close the door. The prisoner would offer his cuffed wrists through the slot and be released. Before returning, the prisoner would present his wrists for cuffing, and only then be allowed back into the building.

One of the doors to such a yard had a small trapdoor just below waist height. Dave explained that a particularly aggressive or dangerous inmate would be led outside in handcuffs. Once outside, the guard would close the door. The prisoner would offer his cuffed wrists through the slot and be released. Before returning, the prisoner would present his wrists for cuffing, and only then be allowed back into the building.

There was a third type of cell, called a “disassociation” cell. These were for inmates who behaved aggressively towards others. In the photo below, the concrete shelf you see is the bed. Dave said that when he began work at the Pen in the early 1970s, those in the “dis” cells got one meal a day, with bread and water at other times. Their mattresses were brought in at 10pm and removed at 7am. In more recent years, they received regular meals and kept their mattresses in the cells, and Dave suggested that the inmates fared better as a result.

The exterior of the “dis” cells.

One of the most surreal aspects of the tour was the contrast between the glorious weather and the very dim interior of the prison; the grim steel and concrete of the cells and the elegance of the limestone exteriors. This is the south face of the main building. Carved into the stone are the three main dates of construction and alteration: 1835, 1893, and 1992.

One of the most surreal aspects of the tour was the contrast between the glorious weather and the very dim interior of the prison; the grim steel and concrete of the cells and the elegance of the limestone exteriors. This is the south face of the main building. Carved into the stone are the three main dates of construction and alteration: 1835, 1893, and 1992.

Beyond the main building, I saw a fenced-in area with a lot of clutter piled up.

It turned out to be the native grounds, where First Nations inmates could observe their faith. Here are the grounds from a distance:

It turned out to be the native grounds, where First Nations inmates could observe their faith. Here are the grounds from a distance:

Maybe what struck me most (after all the props and pieces that must have had their purpose) was the luxuriance of the grass – something we always take for granted, until entirely surrounded by concrete. I’m not sure what inmates of other religions did – there was mention of a chapel, but not of a mosque or anything else.

I think this might be a good place to pause. I was a bit stunned by the end of the tour, torn between lively historical curiosity and a genuine sense of mourning for all the known and unknown things that had happened – possibly in the precise spot where I stood.

I’ll return next week with more photos from the second half of the tour. In the meantime, I’d love to hear from you. What do you think of the place? Have you ever toured an institution like this?

October 16, 2013

That’s my agent!

Hello, friends. This past weekend was the Thanksgiving holiday in Canada. I am still coasting on leftovers (that’s a splendid thing, in my opinion), basking in crisp sunshine, and in total denial of the sudden onslaught of Christmas cack in the retail world.

This is not a terribly new video and I can’t seem to embed it here the way I usually do, but I’m linking to it anyway because hey! that’s my agent! Without further ado, here is Rowan Lawton of Furniss Lawton, with her Top 3 Tips for getting published.

Also, I’m reading Peter Carey’s Parrot and Olivier in America. I’ve said this before, but Peter Carey is absolutely bonkers. I’m adoring it. What are you reading right now?

October 9, 2013

Mythological maidens

Hello, friends. We were in Ottawa this past weekend and I spent several minutes staring, transfixed, at the statue of Sir John A. Macdonald on Parliament Hill. I had cleverly neglected to bring a working camera with me, so this image is ripped, with apologies, from the Public Works and Government Services of Canada website.

statue of Sir John A Macdonald by Louis-Philippe Hébert

I’m interested, specifically, in the slightly-larger-than-life-sized sculpture that adorns the pedestal: the regal-looking woman seated with a spear. There’s a much clearer image of her here, if you’re willing to click through. Or you can just take my word for everything I’m going to say.

I didn’t know who she was, at first: some generic Greek-mythological nymph, I thought. There’s quite a tradition of placing decorative female figures (which I’ll call FFs, from now on) below statues of male politicians. I had read somewhere, years before, that the FFs embodied aspects of the politician’s best-known leadership qualities. Well. If that is indeed the case, Macdonald (or “John A”, as he’s familiarly known in Kingston) was primarily celebrated for an imperious gaze, carelessly worn togas, and very large breasts.

The most striking thing about this statue (the woman is more than an embellishment; she’s a statue in her own right, and much more prominent than Macdonald himself, if you’re standing at ground level) is how extremely young, firm-bodied, and nearly undressed she is. She’s bare-armed, the thin fabric of her toga leaving nothing to the imagination. And she’s wearing very minimal sandals, so that her feet are essentially bare. This is an extraordinary state of public undress for 1895, the year of the statue’s creation by Louis-Philippe Hébert, and a year when respectable women dressed like this.

I suppose that’s the point: the FF is not meant to be a respectable woman, or any kind of real human being at all. She’s a decorative element, the spirit of a person or nation or movement personified. (This one is sometimes referred to as the Personification of Canada.) But it’s another startling reminder of just how casually the female body could be used, even in 1895. It’s also part of a long artistic tradition of male sculptors and painters evading the standards of the day by using “historical” costume to undress female bodies for visual pleasure.

I’ve been wondering how viewers in late-nineteenth century Ottawa responded to the FF. Did adolescent boys flock to view her, to their parents’ consternation? Did MPs pause before it for a few moments’ distraction, during a break in the House of Commons? Or was it simply another semi-nude figure scattered across Ottawa’s terrain? I would dearly love to know.

October 2, 2013

How to mount a penny-farthing

Hello, friends. I’m up against a deadline (Canada Arts Council grant application – my first!), so here’s a fun little instructional on how to mount a penny-farthing bicycle. Bicycles became extremely popular in the 1880s and 1890s and I enjoy thinking about Mary Quinn trying one out, in later life.

As you’ll see, the early designs were for athletic men only; sadly, there’s no chance of riding one of those in a crinoline! So it’s fitting that this video was produced by a group of people at the Mountain Equipment Co-op, in what looks like Vancouver (Yaletown, possibly?).

Now you know exactly what to do the next time you see a penny-farthing for sale on Craigslist.

September 25, 2013

Persistence

Hello, friends. I’ve been thinking this week about life’s important, meaningful, and really unglamorous lessons. Specifically, I’ve been thinking about that Thomas Edison quotation: “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” Or, as John Ruskin put it nearly fifty years earlier, “I know of no genius but the genius of hard work.”

This all came to mind because at Kingston’s WritersFest this coming Sunday, I’ll be hosting a writing workshop given by Tim Wynne-Jones. Part of the hosting gig involves writing an introduction, and so I began reading a little more about Wynne-Jones. I don’t normally research authors; I’m more interested in their work. But maybe I should change my ways!

What struck me most forcefully is Wynne-Jones’s sheer output: by my count, he’s written 3 novels for adults, 17 picture books, 3 collections of short stories, and 9 novels for young people. (And that’s just the fiction. Wynne-Jones engages in critical writing, too!) If you think about how much practice he’s had in shaping a compelling story, it’s no wonder that he’s such an accomplished storyteller. He didn’t just have a gift for words or a particularly inventive mind: he took those talents and never stopped using them.

His is the kind of energy and dedication that might seem daunting, some days. Today, I find it deeply inspiring. I’m early in my career, a relative novice. So: persistence and practice. Those are my by-words this week.

How about you? What are you learning this week? What other unglamorous lessons should we think twice about?

September 19, 2013

Fermentation

I’ve been a very sloppy blogger recently, and for that I sincerely apologize. I didn’t mean to fall into an every-other-week pattern, and I realize it’s Thursday today. I have a specific plan to improve (I’ve blocked out a blogging session each Monday evening) and I hope my weekly post will become a joyful habit, rather than something I cringe to realize that I’ve missed once again.

But I’m here now to talk to you about fermentation! The jars below contain tomato seeds from some of the varieties we grew this summer. This is the first year we’ve tried saving tomato seeds, but our friends Crista and Mike assure us that it’s straightforward. Basically, we choose the ripest, most beautiful specimen possible, scoop out the goo (technical term) and seeds, and put them in a jar. We top it up with a little water – about half as much water as there was goo, by volume – cover it and let it sit. When a thin layer of greyish-white mould grows on top of the water, we drain off the liquid and rinse, rinse, rinse. Then we dry the tomato seeds on a plate on that same sunny window-sill.

Looks like a mad science experiment, don’t you think?

Looks like a mad science experiment, don’t you think?

But it’s not just tomato seeds we’ve been fermenting around here. Firstly, I’ve begun work on the New Book and it’s scaring the pants off me, in a good way. (No, I haven’t begun writing horror. I can’t even read horror. I tried reading Andrew Pyper’s The Killing Circle this summer and had to stop, I was so terrified. And then I had nightmares.) But the New Book is completely different from what I’ve written before: new setting, new time period, first-person instead of third-person, two narrators instead of one… I’m not sure I can do it, and it’s freaking me out, but I adore the challenge.

Another thing that’s fermenting is a visit to Calgary in November, about which I’m so excited. On November 28th, I’ll be reading at two branches of the Calgary Public Library! I’ll post times and locations as soon as I know the details.

And finally, my lovely UK editor just sent me a draft cover for Walker Books’ edition of Rivals in the City. I’m not allowed to share it yet, because it’s still being discussed and refined. But I can tell you that it’s gorgeous…

September 4, 2013

Anita Brookner

Another week, another missed blog post. I’m so sorry, friends. I’ve been wrestling with my sluggish internet connection for far too long, and am hoping to get it sorted out this week. I had no idea that upgrading my connection could be so complicated.

However, I have not spent the entire week on hold or talking to technical support. I have also been reading, of course. Last week, we did a little day-trip to Prince Edward County to pick local blueberries (it’s the tail end of the season; we’ll go during the first week of August, next year) and ended up at Miss Lily’s Café in Picton.

Miss Lily’s serves pretentiously packaged but absolutely delectable coffee from Toronto. And it’s connected to Books and Company, an airy and beautiful independent bookseller with a resident cat. It was hot outside, I felt weary, and the children were industriously painting themselves with ice cream. Nick said to me, “Why don’t you slip in for a browse?”

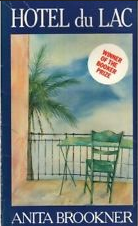

I was only waiting to be asked. I shot inside and, two minutes later, was perusing Books and Company’s small used-book section and asking myself, in genuine astonishment, Why haven’t I ever read Anita Brookner? They were offering a used copy of Hotel du Lac for $3.50. Ridiculous! How could I not?

So. Hotel du Lac.

This is the edition I bought, although someone's attempted to peel off the Booker McConnell sticker.

Nothing much happens in the first half, and the “scandal” constantly, mysteriously mentioned in that first half is thoroughly foolish and predictable. This is the point. The novel is a window into the acerbic, curious, slightly depressive, and uncompromising mind of its protagonist, Edith Hope (“a writer of romantic fiction under a more thrusting name”), who spends a week or so at a Swiss hotel in the off-season.

The novel is beautifully written, with a clarity and precision that’s quite startling to read. And it’s a quiet but steady – intransigent, even – tract about the importance of respecting and holding to one’s own standards and beliefs, even when they offend and inconvenience everybody else.

I’m afraid that sounds like faint praise, but it’s an old-fashioned book in the best sense of the word. It is a success on its own terms, which is precisely what it set out to be.

Have you discovered or rediscovered any authors recently? What are you reading? Also, did you get your fill of local berries this year? I feel a deficiency!

August 21, 2013

The Birth of a Book

August 14, 2013

Fatberg!

Hello, friends! Did you hear about the “fatberg”? It was a 15-ton conglomeration of solid fat found in a London sewer. (This NPR blog post has a photo. If you’re the queasy type, don’t click; just take my word for it.) This thing was 15 tons of congealed fat mixed with disposable wipes. Sewage workers spent 3 weeks hacking it into chunks which were then taken away in “heavy-duty lorries”. They said, “If we hadn’t discovered it in time, raw sewage could have started spurting out of manholes across the whole of Kingston [in suburban London].” Workers are now busy repairing the damage done by the fatberg to the sewer.

You’ve probably noticed my fascination with sewers and the grotty details of urban life. And naturally, the first thing I thought when I heard this was, “Well. This would never have happened in Victorian London.” And it has nothing to do with population growth or advances in kitchen plumbing. Or the fact that baby wipes hadn’t yet been invented.

The first thing is that solid fat was an important resource in the nineteenth century. It was part of English cuisine (beef dripping or bacon fat spread on bread; lard in pastries; fats from all animals cooked into meals) and, if you were poor, an essential source of calories and nutrients. Fat also had commercial value: you could render it down and use it to make soap. If you had an excess of fat, you could sell it around the neighbourhood, or to the scrapman who came to your door. Indeed, fat was relatively expensive: there’s a traditional treat called lardycake, a sort of brioche made with lard and currants. It’s a festive food, associated with special occasions, and part of that is because of the extravagance of kneading sugar, dried fruit, and lard into a bread dough. But I digress. My point is that because of fat’s many uses and significant value, no one would deliberately pour it down the drain.

Even so, a small amount of fat must have found its way into the sewers (greasy dishwater, spills). We know this because in 1862, a journalist named John Hollingshead explored the sewers and and noticed “icicles” of fat clinging to the sewer roof. But remember! At this time, sewers drain straight back into the Thames. And this is where the mudlarks came in handy: poor Londoners, often children, who scavenged through rubbish on the riverbanks. They collected whatever refuse could possibly be recycled or re-used. Any clots of fat they spotted bobbing on the water would have been harvested and sold, too.

We had to wait until the early twenty-first century, and our prodigality with (and simultaneous terror of consuming) solid fats, and our domestic laziness in flushing everything down the toilet, before we could experience the Fatberg. Not really much of an advance, is it?

P. S. You probably don’t need to be told this now but please don’t pour cooking fat down the sink, especially the stuff from your festive turkey or your weekend bacon. Please don’t flush disposable wipes or maxi pads down the toilet. Don’t put hair in the toilet, either. All these things will only come back to get you in the monstrous form of the Fatberg.

P. P. S. Thanks to my friend Sean Burgess, who first alerted me to the Fatberg.