Y.S. Lee's Blog, page 20

May 22, 2013

Birthday brownies

Today we’re having a birthday party for my daughter, who is turning two. TWO. Half of me is in complete denial about this; the other half is self-medicating with chocolate and sugar.

My daughter is opinionated and shy and fierce and funny (so funny) and verbal and stubborn. She’s a lot like me, and utterly unlike me at the same time. One thing we will probably always share, however, is a passion for brownies. (I realize this is hardly unique; who are these people who claim to dislike chocolate, anyway?) So for this birthday bash, we’re having brownies instead of cake.

As soon as I finish up this blog post, I’ll be baking a double batch of my longtime, all-time favourite brownie recipe. These brownies are good enough to make you weep. They’re also brilliant because they use melted butter, cold eggs, and cocoa powder instead of chocolate, so they’re perfect spur-of-the-moment brownies. You can also make it gluten-free by directly substituting any GF flour for of wheat flour. We like teff but really, anything goes.

Alice Medrich’s Best Cocoa Brownies (from Bittersweet, 2003)

10 tablespoons (1 1/4 sticks) unsalted butter

1 1/4 cups sugar

3/4 cup plus 2 tablespoons unsweetened cocoa powder (natural or Dutch-process)

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

2 cold large eggs

1/2 cup all-purpose flour

2/3 cup walnut or pecan pieces (optional)

Position a rack in the lower third of the oven and preheat the oven to 325°F. Line the bottom and sides of an 8″ square baking pan with parchment paper or foil, leaving an overhang on two opposite sides.

Combine the butter, sugar, cocoa, and salt in a medium heatproof bowl and set the bowl in a wide skillet of barely simmering water. Stir from time to time until the butter is melted and the mixture is smooth and hot enough that you want to remove your finger fairly quickly after dipping it in to test. Remove the bowl from the skillet and set aside briefly until the mixture is only warm, not hot.

Stir in the vanilla with a wooden spoon. Add the eggs one at a time, stirring vigorously after each one. When the batter looks thick, shiny, and well blended, add the flour and stir until you cannot see it any longer, then beat vigorously for 40 strokes with the wooden spoon or a rubber spatula. Stir in the nuts, if using. Spread evenly in the lined pan.

Bake until a toothpick plunged into the center emerges slightly moist with batter, 20 to 25 minutes. Let cool completely on a rack. Lift up the ends of the parchment or foil liner, and transfer the brownies to a cutting board. Cut into 16 or 25 squares.

There are a lot of brownie recipes out there, but this is the one I’m prepared to stand by. How about you? If you love brownies, what’s your go-to? And if you are one of the unicorns who really doesn’t care for chocolate, please speak up!

May 15, 2013

A Reader Reports: All Over the Place

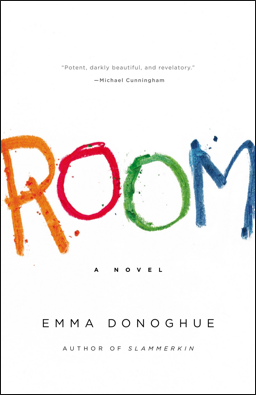

Hello, friends. Last week, I mentioned Emma Donoghue’s novel Room, which I read in just two sittings last week. Apart from that, I’ve been reading in a patchier, less-focused fashion for the past little while. Part of it is because I’m nearing the end of Rivals in the City, so I don’t have as much mental space for other fictions. And part of it is the fact that it’s spring, and I’m restless, and sunshine-starved, and eager to start gardening. So today, I have one book to recommend to you and a few others that I’ve dipped into and plan to keep reading.

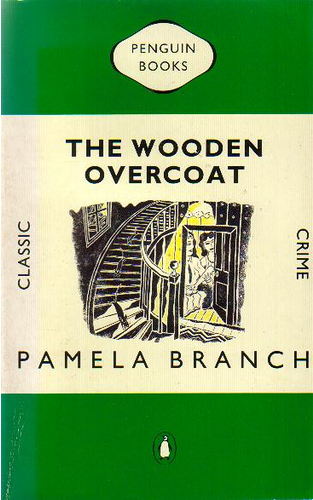

Pamela Branch, The Wooden Overcoat

I’d never heard of Pamela Branch, but I picked this up for its cover and made the decision to buy it based on the author bio: “Pamela Branch was born on a tea estate in Ceylon. She… studied art in Paris and then went on to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London. Returning to the East she lived for three years on a houseboat in Kashmir, trekking in the Himalayas in the summer and skiing in the winter. She travelled extensively in Europe, India, the Middle East and Africa. She died in 1967.”

The novel is vivid and memorable, in a rather unexpected way. It doesn’t start especially well, the solution to the puzzle has nothing to do with the plot itself, and the title has nothing to do with the mystery. There is zero emotional development for any of the characters, who are all two-dimensional types. Yet it’s deliciously, almost appallingly breezy (a houseful of aspiring artists tries repeatedly – and fails repeatedly – to dump a quickly increasing number of corpses, whom they call “the Loved Ones”) and extremely funny. Branch has a brilliant eye for detail (“Fan cleaned her teeth. She was experimenting with a new way of spitting toothpaste when she saw from under her eyelashes that the woman in the opposite window was still watching her.”). But it’s the setting I really adored: 1950s Chelsea, seedy, decrepit, still in the age of ration cards (following the Second World War). And I love that Branch wrote a really funny and gruesome murder mystery by breaking so many rules. I’m eager to read the rest of her small body of work.

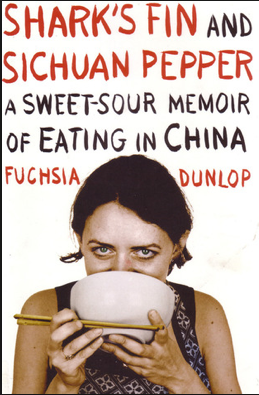

Fuchsia Dunlop, Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China

I’m only a few chapters into this memoir, but I think I object to Dunlop’s subtitle: I suppose some will enjoy the pun on “sweet-sour”, but it would be more accurate to jettison the stereotype and call it “bittersweet”, I think. Or better, simply “A Memoir of Eating in China”. Apart from that, I’m enjoying it tremendously. I have Dunlop’s first cookbook, Land of Plenty (published in the UK as Sichuan Cookery), and cooked from it quite a bit before I began producing 35 meals and snacks each week for small children. (Do the Sichuanese feed their toddlers numbing Sichuan peppercorns? I’d love to know.) But I didn’t realize that Dunlop was such a skilled writer. I am entranced by her descriptions, moved by her account of her first months as a foreign student in Chengdu, and desperate to know how things develop.

Joan Didion, We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live: Collected Nonfiction

Didion in 1970. Photo credit: Julian Wasser/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Confession: I’ve never read anything by Joan Didion. I planned to read The Year of Magical Thinking, Didion’s memoir of losing her husband to a sudden heart attack, but was distracted by other books – and, definitely, a shyness about the subject matter. (After all, I intend to read Julian Barnes’s Nothing to Be Frightened of, too, but I never think to myself, “You know what would be perfect to read next? That one about fearing death.”) But I recently ran across a reference to Didion’s 1968 classic series of essays about the hippie movement, Slouching Towards Bethlehem. The idealism of the hippie movement has been a big topic in our house for the past few months – we’re in a comparable moment of cultural crisis, I think – and so I’m in. I’ve only flicked through, but I think I’m going to become a Didion convert. Her most prominent trait for me so far is, in Graham Greene’s words, “the splinter of ice in the heart of a writer”. I can’t wait to be frozen.

What are you reading? Have you read any of my picks this week?

May 8, 2013

Art and life

Mea culpa, friends. I missed my usual blog post last week (long, boring story: sick children, sick parents, no babysitter). This week, I was planning to write about some of my recent reading, and then the Amanda Berry story broke. I’ve been debating all morning about whether to go ahead with my post because the subject matter is so grotesquely timely, but I think I will.

Last week, I picked up a second-hand copy of Room, by Emma Donoghue. It was nominated for the Booker Prize in 2010.

I had planned to read it some time ago, but other books intervened. This time, I opened the first page and fell right into its clutches. If you’re not familiar with the book, its narrator is a five-year-old boy named Jack who lives, with his mother, in captivity in the place he knows as Room. I couldn’t believe what effective use Donoghue makes of Jack’s voice, his limited and incredibly clear-eyed comprehension of the world. It was beautiful and terrifying and utterly compelling. And then I read the news about Amanda Berry’s recent escape.

I don’t want to capitalize on someone else’s tragedy. But I will say this: at one point, after Jack and his mother are free, a smirky journalist asks them, “So after your rescue…” And Jack’s mother corrects her: “Escape.” Jack’s mother is braver, smarter, and tougher than one can easily imagine, and that’s because she has to be, in order to live. The only other point I want to make is that Room works because it’s the least exploitative telling imaginable of a story that shrieks horror and taboo. It’s about Jack and his mother, their bond, and how they negotiate their worlds.

I’ll talk about other books another day, I think. For now, I just want to remind myself that it’s possible to think about Amanda Berry, Gina deJesus, and Michelle Knight outside the news cycle: without prying questions, without salacious speculation, and with hope for their future. They are more courageous than we can know.

April 24, 2013

When the competition becomes cutthroat

Hello, friends. I have some particularly lovely and extremely immodest news to share with you, this week: The Traitor in the Tunnel has been shortlisted for an Arthur Ellis Award! I’m especially excited because this is Traitor‘s first possible award. As some of you know, A Spy in the House was nominated for three awards and won the Canadian Children’s Book Centre’s inaugural John Spray Mystery Award in 2011. The Body at the Tower was shortlisted for Australia’s Inky Awards. And now it’s Traitor‘s turn! Mary Quinn is three for three! I can’t tell you how exhilarated I am.

The awards will be presented in May. Can you picture it? A gala evening in Toronto for, say, two hundred. Forty or so mystery authors, all vying for prizes. A winner is announced. A blood-curdling scream tears through the audience. The lights go out. Pure mayhem ensues. And, perhaps best of all, I now have the opportunity to make appalling jokes like this for the next six weeks.

In other news, my friend Vee sent me a link to a fascinating article about Victorian walking sticks. Yeah, yeah, walking sticks, I hear you mutter. You will have to read it for yourself and Be Amazed. I would link it here, but it contains some graphic descriptions that I don’t want to impose on those under 18. I will simply offer you my favourite paragraph:

Last Saturday, the Kimball H. Sterling Auction Gallery in Tennessee held a sale of more than two hundred vintage canes, including a great number of what collectors call “system canes.” One was designed for midwives and had a baby scale hidden within it; others concealed a picnic utensil set, opera glasses, an ear trumpet, a perfume bottle, a detachable baby rattle, a blow gun, a winemaker’s thermometer, a folding fan, a telescope, a flask with cork top, a pocket watch, a sewing kit, a compact and mirror, a full-length saw blade, a microscope, a pennywhistle, a set of watercolors and paintbrush, a whistle for hailing a cab, and gauges for measuring the height of a horse. (Wayne Curtis, “Pimp My Walk”, The Smart Set.)

My first thought on reading this was of Amelia Peabody, Elizabeth Peters’s Victorian/Edwardian Egyptologist and sleuth, who carries a specially made cane that conceals a sword, custom-made to her dainty proportions. Did Peters know, or is this a splendid coincidence? My second thought: how can I work one of those into a book? MU-hahahaha!

And that was my week. How was yours? What are you up to?

April 17, 2013

CD and me

Hello, friends. A couple of days ago, I saw a car driving very slowly around the car park of Portsmouth Olympic Harbour in Kingston. This isn’t unusual. The harbour is always busy with runners, walkers, picnickers, coffee-drinkers, dog-walkers, cyclists, and all manner of casual idlers. The thing that caught my eye was the small dog trotting along beside the car. Yes, the dog’s owner was “walking” his dog by driving alongside it. I don’t think I’ve led an excessively sheltered life, but this startled me. We North Americans love our cars and we’ve built our sprawling cities around them. I guess the next logical step is to give up our legs entirely?

If you thought I was going to segue once again to Judith Flanders, you’re absolutely right. In The Victorian City, Flanders asserts: “walking was the most common form of locomotion throughout the nineteenth century. By mid-century it was estimated that 200,000 people walked daily to the City; by 1866 that figure had increased to nearly three-quarters of a million.” What I love is that it’s not just the poor who walked: it was most people, including the rich. “In 1833, the children of a middle-class musician living in Kensington walked home from a concert in the City.” That’s roughly 4 miles and it would take about 90 minutes, according to Google Maps. “Two decades later, Leonard Wyon, a prosperous civil servant, and his wife shopped in Regent Street, then walked home to Little Venice.” That’s about two and half miles, or 50 minutes. And “In 1856, the wealthy Maria Cust returned from her honeymoon, walking with her husband from Paddington to Eaton Square.” Assuming the Custs strolled through Hyde Park, that’s a 2 mile walk which might take 40 minutes.

Not everyone walked for leisure, of course. Working people endured extremely long days, by our standards: shifts of 12, 14 and 16 hours were not uncommon. And they commuted by walking. (No wonder they bought breakfast along the way, eating as they went.) My favourite image of the Victorian walking commute features office clerks: “a thick black line, stretching from the suburbs to the heart of the city… [they] plod steadily along… knowing by sight almost everybody they meet or overtake, for they have seen them every morning (Sunday excepted) for the last twenty years.”

All this puts Charles Dickens’s famously feverish walking in a clearer context. Dickens once walked 30 miles from his home in London to his country house in Kent. (He set off at 2 a.m. after a quarrel with his wife, which helps to explain his average walking pace of over 4 miles an hour!) And in his lifetime, he was famous for passionately, diligently, ceaselessly walking the streets of London, which appear in his fiction in such remarkable and evocative detail. But even if I didn’t have Charles Dickens to cite as a model, I would claim that walking is the only way truly to see a city. That’s how I fell in love with London, too. When I lived in Bloomsbury, as a graduate student, I would get up early on weekend mornings and explore the streets. There were other Londonphiles doing the same thing, and I got to know a few of their faces.

These are golden memories, and writing this post has created in me a new resolve: the next time I have 2 or 3 hours, I’m going to walk part of Kingston I’ve never walked before. It’s hardly Dickens in London, but I’ll take it.

April 10, 2013

A coffee and “two thin”

Hello, friends. At the grocery store recently, I was overwhelmed by the idea of how much energy goes into producing and packaging the food I eat. I bought a bunch of cilantro that was grown in California, with all the ground preparation, seeding, watering, weeding, and pest-deterring that farming entails. It was picked (hopefully by legal labour, not migrant children), washed, roots lopped off (pity, because cilantro roots are delicious in curry pastes), bundled, boxed, and trucked more than 3000km (1900 miles) to Ontario. It was then sorted and driven again to my local supermarket, where somebody arranged them all neatly. All I did was pick the bunch that looked nicest to me. It cost $0.99.

How is this even possible? I know there are economies of scale, but I still find it boggling. And cilantro is about as unprocessed a food as you can buy, packaged only with a printed twist tie. What if you buy a can of tuna? Breakfast cereal, or tropical fruit juice, or a frozen dinner?

Then I read about working-class breakfasts in Victorian London. This is from Judith Flanders’s The Victorian City, which I mentioned last week:

Today, eating out is more expensive than cooking at home, but in the nineteenth century the situation was reversed. Most of the working class… cooked in their own fireplace: to boil a kettle before going to work, leaving the fire to burn when there was no one home, was costly, time-consuming and wasteful… The nearest running water might be a street pump, which functioned for just a few hours a week. Several factors – the lack of storage space, routine infestations of vermin and being able, because of the cost, to buy food only in tiny quantities – meant that storing any foodstuff, even tea, overnight was unusual.

Consequently, working-class people bought breakfast from coffee-stalls on the street, where a cup of coffee and “two thin” – that’s two thin slices of bread-and-butter – might cost half a penny or a penny, depending on where you lived. This sounds very cheap to us, of course. But let’s consider that in the context of working-class incomes.

According to Flanders’s research, a coffee-stall holder would typically work nine hours a day (starting late at night, or at 3 or 4 in the morning), six days a week, every day of the year. For that labour, he or she would earn about £30 a year. That’s an average daily gross income of about a shilling, or twenty pennies. From that, the stallholder must rent or maintain his coffee-stall; buy fuel, coffee, bread, butter, and haul water for the coffee-stall; and, of course, feed and clothe his family, and keep them warm and housed. All on an income of a shilling a day, or 24 ha’penny cups of coffee. It’s an astonishing portrait of subsistence.

Let’s flip it around in modern-day terms. The closest I have to a streetside coffee-stall is the Tim Horton’s (a doughnut shop) up the street, where coffee and a bagel costs about $2.50. If you were to set up as a streetside coffee-stall selling coffee-bagel combos for $2.50, and you had 24 customers in a nine-hour shift, that’s a take of just $60 a day. If you worked 6 days a week for every week of the year, you would gross $18, 720. From that, you would need to pay for the same things: rent or repairs on the coffee-stall; coffee, bagels, butter, a water supply, fuel; your own rent, and the needs of your family. Subsistence again. You’d be hard-pressed to buy three coffee-and-bagel meals a day for your family of four.

Converting money between the nineteenth century and the present day is very complicated and I don’t want to claim that these are precise equivalents. But this is a vivid and immediate way of thinking about food, energy, and value, when many of us are so extremely privileged. It makes my cilantro look both cheap and frivolous.

April 3, 2013

The Berners Street Hoax

Hello, friends. Many of you know that I love Judith Flanders’s work. She writes marvellously detailed social histories and her special area interest is the Victorian period. I highly recommend both The Victorian House and Consuming Passions for anyone interested in Victorian daily life, and The Invention of Murder is irresistible for those, like me, who love mysteries and detective fiction. Really, if I could choose to have the contents of one person’s brain imported directly into my own, I think I’d choose Flanders.

And she has a new book out! When I saw the title, The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’s London, I yelped with excitement. And when I actually received the book (it was a gift from Nick), its beauty made me gasp.

This image doesn't do the cover justice. The pinkish-cream half is a separate band of paper that wraps around the hardcover, like a mini-dustjacket. It's beautifully antiqued, with subtle faux-foxing, and the title and borders are in gold.

I’m now starting to dip into it and I will report back when I’ve finished the book, but the first thing I read was too good to resist telling you about now. I know I’ve missed April Fool’s Day by two days, but I think you’ll find this worthwhile.

Flanders opens with an incident called the Berners Street Hoax, which begins “early one morning in November 1810, long before breakfast”, when a chimney sweep knocks on the door of 54 Berners Street, saying he has been sent for. The residents say no, and close the door. This is the sort of minor annoyance that must happen to all tradespeople from time to time. But what happens next?

According to Flanders, “soon the house was besieged by sweeps, all claiming they had been summoned. They were swiftly followed by dozens of wagons bringing coal… legions of fishmongers” and, she quotes, “piano-fortes by the dozens… two thousand five hundred raspberry tarts from half a hundred pastry-cooks – a squad of surgeons – a battalion of physicians, and a legion of apothecaries – lovers to see sweethearts; ladies to find lovers – upholsterers to furnish houses, and architects to build them – gigs, dog-carts, and glass-coaches”.

And this is just the beginning! Flanders is quoting from what sounds like a street ballad (it’s not cited in the end notes), so there’s more than a hint of exaggeration, here. (I question the 2500 raspberry tarts: it’s November, so where did the raspberries come from? I’m happy to believe in apple tarts, though.) But, for what it’s worth:

The surgeons first, armed with catheters, arrive

And impatiently ask is the patient alive.

The man servant stares – now ten midwives appear,

‘Pray, sir, does the lady in labor live here?’

‘Here’s a shell,” cries a man, ‘for the lady that’s dead,

My master’s behind with the coffin of lead.’

Next a waggon, with furniture loaded approaches,

Then a hearse all be-plumed and six mourning coaches,

Six baskets of groceries – sugars, teas, figs;

Ten drays full of beer – twenty boxes of wigs.

Fifty hampers of wine, twenty dozen French rolls,

Fifteen huge waggon loads of best Newcastle coals -

But the best joke of all was to see the fine coach

Of his worship the mayor, all bedizen’d, approach;

As it pass’d up the street the mob shouted aloud,

His lordship was pleased, and most affably bow’d,

Supposing, poor man, he was cheered by the crowd…

And it doesn’t end there! After the Lord Mayor, there came “rows of carriages of the city’s grandees, all invited to a party” (Flanders), the chairman of the East India Company, the Governor of the Bank of England, and the Duke of Gloucester.

It’s challenging to visualize a prank on this scale: traffic jams, tears of frustration, frantic denial, roars of indignation and, most of all, the sheer number of onlookers who must have flocked to the scene. Terrific, in every sense of the word.

How was your April Fool’s Day? Mine was perfectly tame, and I confess myself relieved.

March 27, 2013

“How the Mid-Victorians Worked, Ate, and Died”

Hello, friends. Today, I want to point you towards a super-interesting public-health article that analyzes (in broad strokes, obviously) the rural working-class Victorian diet. I don’t know about you but when I think of Victorian cuisine, my first thoughts are of Mrs. Beeton, or else of Victorian celebrity chefs likes Alexis Soyer and Charles Elmé Francatelli. The food is elaborate, involved, constructed: blancmange. Meat boiled forever. Dessert sculpted into the shape of a giraffe.

Or else I think of the hungry poor, who ate whatever they could (ill-)afford: any vegetables they could scrounge, some stale scraps of meat if they were lucky, a lot of cheap bread. As a result, I tend not to think of Victorian food as healthful or appetizing. I had always assumed that the Victorians were much like us: the rich tended to overeat and suffer from diseases of affluence, while the poor remained undernourished.

But this article, by Paul Clayton and Judith Rowbotham, proposes a very different picture: a “superior” diet of fresh meat, fish, vegetables, and seasonal fruits. It argues that by 1850, improvements in farming technology combined with new transportation (bringing fresh food into urban centres) to create an adult life expectancy that “matched or surpassed our own”, and a distinct “health and vitality… [that] that powered the transformation of the urban landscape at home, and drove the great expansion of the British Empire abroad”. Apparently, the average rural Victorian labourer worked hard (and walked as many as 6 miles to and from work), ate a ton (4000 calories a day!), and enjoyed extremely good health as a result.

I haven’t yet read any responses or analyses to this article, but I’m intrigued. There are plenty of gaps – what of the rich, what of the poor, what of the new middle-classes who sat at desks all day? – but I’m willing to buy the case they make for the diets of the labouring classes – at least, in times of plenty. What do you think?

(Thanks to Mark’s Daily Apple, where I first saw the article linked.)

March 20, 2013

Furnishings for the Middle Class

Hello, friends. This past weekend, we learned that Turk’s, our favourite antique-y store in Kingston, is closing. We’re really crestfallen because over the years, we’ve ended up buying most of our furniture there. Turk’s (est. 1902 by J. Turk) filled an important gap in Kingston: older wooden pieces in decent condition. They were never serious antiques (there are some scarily high-end antiques dealers in town), and thus they were often in our price range. Our decision-making process went like this:

1. We need X. Can we make one, thrift one, or do without? If no, proceed to Turk’s.

2. Is there anything cool at Turk’s? Yes, there is always something cool at Turk’s.

3. Do we really, really like it? If no, return to step 2. If yes, approach item with caution.

4. Does it smell musty? If yes, return to step 2. If no, find price tag.

5. Is it the same price (or less) as an X from Ikea? If yes, purchase. If no, return to step 2.

I’m so sad to see the end of this era. But as we were poking around in a mist of nostalgia (Turk’s has some vinyl and a few books, too), Nick found an amazing (and ridiculously appropriate, given the circs) book for me! It’s called Furnishings for the Middle Class: Heal’s Catalogues, 1853-1934. I am beyond excited to have a bound volume of so much mid- to late-Victorian aspiration, complete with prices and illustrations. I could read it all day.

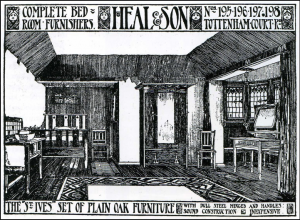

What’s immediately intriguing about the catalogues is that they tend to begin with the least expensive items: “Plain Beds for Servants”, for example, or a White Beech Bedroom Chair. You have to keep reading before you get to things like the “‘Princess Maud’ Suite, painted white, with Louis XVIth enrichments, consisting of 3ft. Wardrobe with Plate Glass Door, 3 ft. Dressing Chest and Glass, 2 ft. 6 in. Washstand (Marble Top), Chamber Pedestal, 2 Chairs” for £10 10 0 (that’s ten pounds, ten shillings). And I’m now restraining myself from typing out even more furniture descriptions. Instead, here’s an advertisement from the end of the century.

What’s immediately intriguing about the catalogues is that they tend to begin with the least expensive items: “Plain Beds for Servants”, for example, or a White Beech Bedroom Chair. You have to keep reading before you get to things like the “‘Princess Maud’ Suite, painted white, with Louis XVIth enrichments, consisting of 3ft. Wardrobe with Plate Glass Door, 3 ft. Dressing Chest and Glass, 2 ft. 6 in. Washstand (Marble Top), Chamber Pedestal, 2 Chairs” for £10 10 0 (that’s ten pounds, ten shillings). And I’m now restraining myself from typing out even more furniture descriptions. Instead, here’s an advertisement from the end of the century.

I also found a photo of the interior of Turk’s as you walk in, here. Yes, those are building’s the original pressed-tin ceilings. Farewell, Turk’s. And thank you for everything.

March 13, 2013

Winter, redux

First, there was birdsong. The light changed. There was even a big thaw. Today, we have… big fat snow flurries? Sigh. Ontario winters get me every time.

The only reasonable thing to do at this point is make another massive curry (I can’t recommend this one highly enough) and crack open a fat book. Nick started David Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet last night, and I embarked (it really does feel like an embarcation, in the best possible way) on Judith Flanders‘s Consuming Passions: Leisure and Pleasure in Victorian Britain. It starts well. Book report to follow.

How are you? Is it spring, where you are? And if so, could you please take a deep breath and blow a little zephyr this way?