Y.S. Lee's Blog, page 14

August 6, 2014

West Coast Bounty

Hello, friends. We’re in Vancouver! For me, being on the West Coast in August means a bounty of local fruit: blueberries, cherries, peaches, nectarines, apricots and blackberries, in particular. My parents live near a stretch of the Fraser River and its banks are dense with wild blackberry bushes (also crabapples, snowberries, and apparently salmonberries, though I haven’t seen any of those). See what I mean?

Every time we go for a walk, we end up having a blackberry snack. If we ever manage to pick more than we eat on the spot, I’m planning to make a batch of blackberry freezer jelly.

The bounty isn’t limited to fruit, of course. I’ve long admired the community garden plots built along some 11 km of disused railway tracks on Vancouver’s west side. The gardens are charming, aesthetically diverse, and bursting with life. They’re an annual inspiration for our own gardens, and a lovely reminder of what we’ll return to. They’re also now now under an eviction notice: CP Rail is planning to raze them, as part of a dispute with the City of Vancouver.

The wrangling could go on for a long time yet. Before anything else happens, here are some shots of the Arbutus Community Garden plots along East Boulevard.

This is the most elaborate and established-looking of the plots. Its bulletin board advertises “the world in a garden”, offering garden shares to interested locals and organic gardening workshops for children. Their shed is a thing of beauty!

We’ve been talking about building a hoop house, like these gardeners are doing:

You cover it with sheets of polythene, like so:

And it becomes a miniature, morphable greenhouse. I’m ridiculously excited at the prospect of extending our growing season. We also saw growing frames made of old bicycle wheels:

While I love the way it looks, I’m not diligent enough to camouflage a water drum:

And sometimes, the temperate West Coast climate makes me sigh with envy. Look: grapes!

The lighting is terrible in this shot, but please believe me when I say that these gardeners are actually growing kiwi. Kiwi! They’ve trained the slender tree trunk to crawl horizontally atop their fence.

Finally, after an afternoon’s hard work, these gardeners can relax and admire their heap of freshly picked beets.

I’m only in the city for a week or two each year, but I would be so sorry to see these gardens go. Let’s hope CP Rail and the City of Vancouver sort themselves out and do what’s best for the community in general.

July 30, 2014

The Legendary Garrett Girls

Hello, friends! Last week, I sent off the first clean draft of my short story, “The Legendary Garrett Girls”. It’s going to be one of fifteen stories in an anthology called Petticoats and Pistols, edited by Jessica Spotswood and published by Candlewick Press.

This is only a first draft, and there are several rounds of editing to come. Still, I’m thrilled to have a full, clean draft written.

This is Gracie E Robinson, of Dawson, YT, in 1898. She doesn’t appear in my story, but she embodies the spirit I was after. (image credit: EA Hegg, U of Washington, Hegg 3063)

Today, I thought I’d share with you the story’s epigraph, which inspired the whole thing:

“They now say there are more liars to the square inch in Alaska than any place in the world.”

– The Seattle Daily Times, August 17, 1897

Doesn’t that just BEG for a fictional escapade? I couldn’t possibly have resisted.

July 23, 2014

Our house cookies

Hello, friends. The past couple of weeks has been oddly temperate, for Kingston in July: cool at night, sunny and warm by day. To my mind, during weather like this, the obvious thing is to bake up a stash of treats against the return of our usual heat and humidity.

The recipe below is not mine. It belongs to French pastry chef Pierre Hermé and American food writer Dorie Greenspan, and while individual palates vary so widely, I feel confident in pronouncing it divine. Everyone I’ve shared these cookies with demands the recipe.

The only quibble I have with the recipe is its title. When Greenspan first published the recipe in 2002 she called them Korova Cookies, after Hermé’s Paris restaurant. Since then, she’s renamed them World Peace Cookies (because they are “all that is needed to ensure planetary peace and happiness“). I see that it’s intended as a joke. I also understand that recipe titles should pique your interest. But I really can’t bring myself to call them WPCs. So: Korova Cookies. Chocolate Sablés. We just call them our “house cookies”.

The original recipe is here, and in a million other places. I like to use whole kamut flour because it enhances the cookie’s sandy texture. And while the texture of gluten-free variations usually suffers, this one is really close. I also replace a portion of the chocolate with cacao nibs, for extra crunch and intensity.

Korova Cookies (with a gluten-free variation)

1 1/4 cups (175 grams) kamut flour, or gluten-free flour mix (measure alternative flours by weight)

1/3 cup (30 grams) Dutch-processed cocoa powder

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

1/4 tsp psyllium husks, if making the gluten-free variation

1 stick plus 3 tablespoons (5 1/2 ounces; 150 grams) unsalted butter, at room temperature

2/3 cup (120 grams) packed light brown sugar

1/4 cup (50 grams) sugar

1/2 teaspoon fleur de sel or 1/4 teaspoon fine sea salt (double this if making the gluten-free variation, as the GF flours tend to mute the salt flavour)

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

5 ounces (150 grams) bittersweet chocolate, chopped into small bits (or 100 grams chocolate plus a handful of cacao nibs)

1. Sift the flour, cocoa, and baking soda (and psyllium husks, if using) together. Beat the butter until soft and creamy. Add both sugars, the salt, and vanilla extract and beat for another minute or two. Add the sifted dry ingredients. Mix only until the dry ingredients are incorporated—the dough will look crumbly, and that’s just right. For the best texture, you want to work the dough as little as possible once the flour is added. Toss in the chocolate pieces (and cacao nibs, if using) and mix only to incorporate.

2. Turn the dough out onto a smooth work surface and shape it into two logs that are 1 1/2 inches (4 cm) in diameter. Wrap the logs in plastic or parchment and chill them for at least 2 hours and up to 3 days.

3. Center a rack in the oven and preheat the oven to 325°F (165°C). Line two baking sheets with parchment paper and keep them close at hand.

4. Working with a sharp thin-bladed knife, slice the logs into rounds that are 1/2 inch (1.5 cm) thick. (The rounds will probably crumble and break; just squeeze them together.) Place the cookies on the parchment-lined sheets, leaving about 1 inch (2.5 cm) spread space between them.

5. Bake only one sheet of cookies at a time, and bake each sheet for 12 minutes. The cookies will not look done, nor will they be firm, but that’s just the way they should be. Transfer the baking sheet to a cooling rack and let the cookies stand until they are only just warm or until they reach room temperature—it’s your call. Repeat with the second sheet of cookies.

If you try these, let me know how you like them! Also, am I being overly sensitive about the world peace thing?

July 16, 2014

Wildlife

Hello, friends. It’s been a busy week in the garden! We’ve had a ton of rain and the vegetables are going berserk. The only catch is that so far, we’ve eaten almost none of what we’ve grown. The reason? There’s a family of groundhogs living at the back of our garden. We thought they were awfully cute in the early spring, when the babies were small and they ate mostly clover.

We think there are four or five, although short of tagging them (Nick suggested colour-coded bow ties) we can’t know for sure. But WOW, groundhogs eat a lot! They soon tired of clover and made their way through our kale, pak choy, green beans, snow peas, and strawberries. We seldom catch them in the act (although one of the babies tried to enter the house through our screen door). We tried blocking their main burrow entrance (they always have a few alternative exits), sprinkling noxious odours (tea trea oil, urine) around the hole, loud noises, etc. And yet they persisted.

This week, we borrowed a trap from a neighbour. He’s caught four or five so far this year, and relocated them to a local conservation area. He was keen to show us his way. So we baited the trap with broccoli and set it out overnight. In the morning…

Whoops!

This baby raccoon was too curious for his own good. Raccoons are a minor urban pest but they don’t eat our vegetables, so I let this guy go. I baited the trap again and we went out for the day.

AND LOOK!

Gotcha!

Nick took this fellow out for a drive and released him. And the next day, we harvested some green beans. We’re going to keep baiting the trap and hoping for the best. Because we are veghogs.

July 9, 2014

To read: perchance to sleep

Hello, friends. Most nights, before I sleep, I read. This is a constant tension: I always want to read more. I know very well that I should sleep more. And the two seem mutually exclusive.

That aside, I thought I’d share my current stack of books with you.

From the top:

Fancy Cycling, by Isabel Marks. This is a delightful photographic catalogue of the kinds of tricks Edwardian children, ladies, and men can perform on bicycles. Most of them are astounding.

This is one of the simpler stunts but I love how the rider is looking directly into the camera. The photo feels very modern, despite her hat and long skirt.

The Shadow of the Wind, by Carlos Ruiz Zafón. My friend Trina lent this to me a few months ago and I’m fewer than 50 pages in. Sorry, Trina! I didn’t find it immediately compelling but she loves it so much that I plan to carry on. It’s just that all my other reading is getting in the way…

On the Yankee Station, by William Boyd. This is Boyd’s first collection of short stories, written before his first novel but published afterwards. It’s a bit uneven but very funny and strange and vivid. I began reading it for short-story inspiration (I’m writing one myself) but kept on because I love being in Boyd’s presence.

Jungle Soldier, by Brian Moynahan. A biography of my new hero/historical boyfriend, Freddy Spencer Chapman. Freddy’s a classic stiff-upper-lip subject and the biography is commensurately very thin. It fills in some details from his early and late life, but I’m better off reading…

The Jungle is Neutral, by F. Spencer Chapman. This is my current favourite book and perhaps my favourite work of nonfiction ever. I really hadn’t expected to like Freddy so much. I was braced for a man of his generation (born 1907): a social snob, an unreflexive racist, an unapologetic colonialist. This isn’t the case at all. Freddy is immensely curious about the world, entirely willing to judge people on their individual merits and flaws, and endearingly passionate about food, even while suffering from bullet wounds, pneumonia, chronic malaria, ulcerated legs, blackwater fever, tick typhus, dysentery, and I-don’t-know-how-many-other ailments. Here’s how terrific this memoir is: I’ve been following Nick all around the house, reading excerpts to him. Another measure of how much I love it: I’m halfway through and already mourning the fact that it must end.

Two Years in the Klondike and Alaskan Gold Fields, 1896-1898, by William B. Haskell. I bought this in Ketchikan, Alaska, at a terrific indie bookstore called Parnassus Books. Haskell is very enjoyable company and reading him is such a lovely way to relive a family holiday while becoming familiar with the setting of my short story.

Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899, by Pierre Berton. It’s impossible to avoid Pierre Berton when you’re researching the Gold Rush. I lucked into this copy at the library’s used-book sale, and it’s been useful as a representative of the most romantic, legend-building, to-hell-with-historical-documentation view of the Klondike.

There it is: my reading brain, exposed. What are you reading, at the moment?

July 2, 2014

5 Things About My Work-in-Progress

Hello, friends. The other day on Facebook, my friend Stephanie Burgis posted her answers to a meme, “Five Things About Your Work-in-Progress”. I was delighted! I read it, thinking, “Oh, it’s so great to hear more about what she’s up to!” Then I realized that I, um, NEVER talk about my work-in-progress. One reason is because I’m constitutionally secretive and vaguely superstitious about unpolished work. At some level, I seem to believe that if I discuss it in too much detail, my computer (or worse, I myself) will be hit by lightning. The second reason is because I’ve always assumed that nobody would ever be interested. Judging from my response to Steph’s post, I’m wrong about that. So I’m squaring my shoulders (both literally and metaphorically). Here we go:

1. I actually have 2.5 works in progress. For me, this is a lot. I’m writing the novel I refer to as The Next Book (more below). I’m also writing a short story for an anthology called Petticoats and Pistols, edited by Jessica Spotswood (again, more below). And starting in September, I’m joining The History Girls as a regular blogger. My first post, about historical fiction as a genre, goes up on September 3 and I’m now planning a second, about the history of Kingston Penitentiary.

2. I’m really nervous about the short story because it’s meant to be only 5000 words long. I have no idea how I’m going to compress so many ideas into such a short space! Its working title is “The Fabulous Garrett Girls” and it’s about a pair of sisters running a tavern in Skagway, Alaska during the Gold Rush, and their confrontation with the legendary con man, Soapy Smith. I’ve absolutely adored the research for it but now I have to compress it all into a (hopefully) rollicking story about a pair of accidental con artists. Wish me luck!

Broadway (the main street), Skagway, AK, in 1898

3. As part of my research for “The Fabulous Garrett Girls”, I’ve once again been immersed in scenes of heavy toil, knee-deep muck, women wearing men’s trousers, women performing unusual jobs, travel by horse and on foot, and people who are not what they say. Sound familiar, fans of the Agency? The only thing missing, really, is a good romp in a sewer. I haven’t been able to find any enthralling narratives of frontier sewer action. Yet.

4. The Next Book, as I’ve been calling it, also has a working title: Monsoon Season. It’s set in the British colony of Malaya (now two independent countries, Singapore and Malaysia) during the Second World War. I’ve been working on this book for a long time – almost 12 months at this point. That includes two false starts, during which I tried to figure out just how I was going to tell this story. I’ve now found a structure that seems to work, and I’m fine-tuning my narrative voices. Yes, voices: there are three. It’s been quite complicated and nerve-wracking. I’m still not quite sure I can pull this off. But I remain optimistic.

Explorer, soldier, and naturalist Freddy Spencer Chapman (he’s the one in knee socks)

5. My research for Monsoon Season led me to the extraordinary figure of Freddy Spencer Chapman, a British explorer, naturalist, and soldier whose life really should be made into a film. For about three years during the Japanese occupation of Malaya, Spencer Chapman was considered missing and presumed dead by the British Army. In fact, he was alive, hiding in the dense Malayan jungle, and performing work that included destroying bridges and trains, attacking Japanese soldiers, and collaborating with local Communists who were also resisting the Japanese military government. Despite being ill for most of his time in the jungle (at one point, he was in a kind of coma for 14 days and only realized this after the fact, when he noticed the lapse in his journal entries), Spencer Chapman also kept notes on bird species and collected plant seeds to send to Kew Gardens. I’m about to begin his memoir of that period, The Jungle is Neutral.

And that’s what I’ve been up to. Exciting times! What are you writing and reading, friends?

June 25, 2014

You Are Stardust

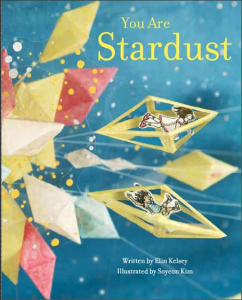

Hello, friends. Today, I want to share with you a book that I happened upon in my local indie bookseller, Novel Idea. It’s a picture book called You Are Stardust, by Elin Kelsey with artwork by Soyeon Kim.

It blew my mind.

It starts with perfect, confident simplicity: “You are stardust. Every tiny atom in your body came from a star that exploded long before you were born.”

As it begins, so it continues. Every statement in the book is grounded in scientific fact. Every sentence is calm and minimal, yet a powerful spur to wonder. “You started life as a single cell. So did all other creatures on planet Earth.”

“Salt still flows through your veins, your sweat, and your tears. The sea within you is as salty as the ocean.”

“From ocean to sky to land and back again, the same water has been quenching thirsts for millions of years.”

“Each time you blow a kiss to the world, you spread pollen that might grow to be a new plant.”

I actually find it difficult to articulate how profound and inspiring I find this book. I want to gush. I want to buy a copy for every child I know. And I want to sit quietly and read and re-read it, and stare for hours at the exquisite illustrations by Soyeon Kim.

The book itself is packaged as a kind of gift. If you unwrap the dustjacket, you’ll find photos of each diorama Kim built, which were then photographed to create the illustrations. Kim offers notes on specific elements of each diorama: flowers picked from her garden and carefully dried, paper dyed and curled to look like waves. And the endpapers show some of Kim’s notes on her artistic process.

There’s also this video to walk you through the illustrations and how they changed as a result of conversations between Kim and Kelsey.

I hope you enjoy it. And then I hope you run out and buy/borrow a copy of You Are Stardust and let it blow your mind, too.

June 18, 2014

The Cat Came Back

Hello, friends. On Father’s Day, our family drove out to the United Church hall in the village of Battersea, Ontario, for a concert by children’s musician Gary Rasberry. It was a lovely afternoon with thoughtful and inventive music for children, astoundingly gifted musicians (including Sheesham Crow, from Sheesham & Lotus), and church-lady pie.

True story:

Me: May I have two coffees, please?

Church lady: That’ll be $4.

Me: Oh, and a slice of pie, too.

Church lady: Okay. That’s… $4.

One of the songs Gary & friends performed is “The Cat Came Back”. If the song is new to you, know that it’s a gleefully nasty folk song about the attempted destruction of an unloved cat. Despite dynamite, electrocution, guns, drowning, hot-air balloons, train wrecks and the mysterious disappearance of several humans, the cat prevails. It’s the kind of macabre thing that so many children love. Plus, it’s ridiculously catchy.

If you’re Canadian, you probably associate the song with children’s musician Fred Penner. (Here’s a recent-ish video of Penner performing “The Cat Came Back” for an audience of adults, many of whom probably grew up watching his TV show.) I’d always assumed that Penner wrote the song but at the concert, Gary and Sheesham mentioned that the song dates back to the American minstrel tradition of the nineteenth century.

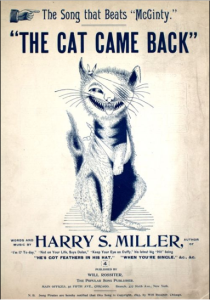

“The Cat Came Back” was originally published in 1893 by Harry S. Miller, but the first commercial recording seems to have been some 30 years later, in 1924. I really like the idea that the song got established in performance, both public and private (I picture a multi-generational family gathered around a slightly-out-of-tune piano and bellowing, all together, “It just wouldn’t stay a-waaaaay!”) before finding its way into the commercial music industry.

But here’s the main thing that I really must mention in the history of “The Cat Came Back”: Miller’s original lyrics are written in African-American dialect (Georgian, according to wikipedia), which means they feature non-standard grammar and creative spellings to signal pronunciation: “of” becomes “ob”, “yellow” becomes “yaller”, and “with” becomes “wid”. So the song isn’t just about an irate and desperate Mr. Johnson who will do anything to be rid of his cat; it’s about black dialect and a black singer. (I imagine Mr. Johnson is black, too, although that’s ambiguous.) A large part of the song’s comedy is predicated on black people saying and doing laughable things. Don’t believe me? Its original title was “The Cat Came Back: A Nigger Absurdity”.

I’m not suggesting that we should stop singing “The Cat Came Back”. That would involve cutting a hole in American folk music history. And the joke works perfectly in standard English, stripped of its racist context. But, as ever, we need to be alert and to remember all the peculiar and shadowy aspects of our cultural histories. Performers like Gary and Sheesham are slipping clues to the adults in the audience. And I’m grateful to have my horizons widened through an offhand comment at a children’s music matinée.

June 11, 2014

Shakespeare’s English

Hello, friends. I’ve had a copy of David Crystal’s The Stories of English for a long time now, but never managed to get around to reading it. That’s about to change.

Today, I came across a fascinating article about what English accents used to sound like. In it, linguist Gretchen McCulloch explains that there was a major shift in English pronunciation during the late eighteenth century. Because North American colonies were founded before that transition, Canadians and Americans now speak with accents that are derived from the old pronunciation.

The most obvious example, according to McCulloch, is our pronunciation of Rs (in words like car, yard, and farm). Basically, the English used to do it; the emigrants who first settled here did it; and so we still do it. In contrast, Australia was used as a penal colony after the linguistic shift, and that’s why Australians today don’t pronounce their Rs.

Anyway, embedded in McCulloch’s short article is this terrific video featuring linguistics expert David Crystal and his actor son, Ben Crystal. In it, they demonstrate what Shakespeare sounded like in “Original Pronunciation”, or OP.

If you don’t want the fluff about the rebuilt Globe Theatre in London, skip ahead to 3:00. But don’t miss the Crystals’ compare-and-contrast readings of Shakespeare! It’s startling, inspiring stuff.

June 4, 2014

Ahistorical Fiction

Hello, friends. Here we are: this week, in the UK and Australia, Walker Books publishes Rivals in the City. (The US/Canadian edition will come in February 2015 from Candlewick Press.) I am tremendously excited to see this fourth novel come into the world and meet its readers. I’m also rather wistful: it’s the last Mary Quinn mystery.

Hello, friends. Here we are: this week, in the UK and Australia, Walker Books publishes Rivals in the City. (The US/Canadian edition will come in February 2015 from Candlewick Press.) I am tremendously excited to see this fourth novel come into the world and meet its readers. I’m also rather wistful: it’s the last Mary Quinn mystery.

The part I’m saddest about? I’ll never again write dialogue between Mary and James. I absolutely adored writing them in and out of arguments. The part I’m happiest about? Leaving Mary poised to make her way in 1860s London, entirely on her own terms. To me, this feels like a triumph.

Like all good endings, this final pub date has made me think about Mary Quinn’s beginnings. One of the best questions I’ve ever been asked, as a writer, was a couple of years ago at Kingston WritersFest. It was from a high school student. While I can’t remember her precise words, it went something like this: “The premise for the Agency is clearly a fantasy. But you’ve chosen to write the novels as realist historical fiction. Why did you decide to blend the two?” Isn’t that a beautifully analytical question?

To mark the publication of Mary Quinn’s last adventure, here’s my answer, in the form of a short essay about what I call “ahistorical fiction”. (If you don’t want to read expository writing, I’ve posted the first chapter of Rivals in the City here, for you.) If you’re curious about the idea of ahistorical fiction, please read on. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Ahistorical Fiction

My title is neither a typo nor a lousy pun. I really meant “ahistorical fiction”, which I define as a subset of historical fiction that includes elements which stand apart from mainstream history. I’m not talking about fantasy (set in an imagined world that may or may not straddle our own) or speculative fiction (which includes fantastic, supernatural or futuristic worlds). Neither do I mean fiction that is broadly anachronistic (Napoleon with a smartphone!) or counter-historical (undermining the very idea of history). Today, I’m here to defend the use of ahistorical elements in otherwise realist historical fiction.

The obvious, reflexive objections are:

1. Doesn’t that undermine historical fiction as a genre?

2. Why bother with ahistorical fiction at all? Why not write something else?

My short answers:

1. No, it enriches it.

2. See answer no. 1.

Are you ready for my longer answers? In the afterword to , Elizabeth Wein explains some of her plot choices and acknowledges that her first priority is not perfect historical accuracy. Instead, she says, her goal is simply to tell a really good story. I like that justification; it’s at the core of my writerly impulse, too. And Wein makes it sound so clean and easy. But I think it skims over some of the tricky decisions and border-drawing that happens when writers carefully include ahistorical elements in their work.

When we use ahistorical elements, we’re being selective. We’re not haphazardly inventing conveniences to rescue a stalled plot or sprinkling in some cute embellishments. Instead, we’re trying to open up our understanding of historical relationships. For Wein, this is having an English girl pilot crash-land in Nazi-occupied France. For me, in the Mary Quinn mysteries, it’s the creation of a women’s detective agency in 1850s London. In both cases, the ahistorical element is technically possible (just about). For my detective agency, I’m leaning on two historical precedents: the beginning of progressive girls’ education in the mid-nineteenth century (Bedford College was founded in 1849) and the career of Aphra Behn, the eighteenth-century playwright and spy. (The Agency is also an affectionate homage to Miss Climpson’s “typing bureau” in Dorothy L Sayers’s Peter Wimsey novels.) These specific historical leaps allow writers a different way of asking the big question at the heart of historical fiction: what if?

When I began to write A Spy in the House, the first Mary Quinn novel, I wanted to focus on an orphan girl without any advantages of money, social status, or education. I quickly realized that such a novel would be a swift, bumpy descent from poverty to prostitution to prison and, almost inevitably, early death. (This last sentence basically gives away the plot of Emma Donoghue’s Slammerkin, which I highly recommend. It’s a gorgeously excessive tragedy not the least bit diminished by its inescapable ending.) Yet I wanted to rescue my protagonist, not sentence her to death. I decided to play with ideas of power by giving my orphan, Mary, a quasi-realistic opportunity to make her own way in the world: a handful of allies, a good education, a job that was more than underpaid drudgery. She would carry with her the baggage of her childhood suffering, but she would have a second chance. It was my way of using fiction to right an ongoing injustice. It was also a way to, in David Copperfield’s words, make Mary the hero of her own story.

Ahistorical elements in historical fiction are a way of rearranging the furniture. They’re also a bit like social history’s quarrel with the great-man narrative of history: what about everybody else? What if we shift our focus away from what’s always been there, and ask a different question? The use of ahistorical elements is born of love and respect for history and historical fiction. As in any relationship, though, sometimes you bump up against its limits. Sometimes you crane your neck, trying to see what exists outside its bounds. Sometimes, a fresh idea knocks you breathless. And once you’ve considered it, it helps you to see your old love anew.