Y.S. Lee's Blog, page 10

May 5, 2015

A History of Violence

A couple of months ago at the launch party for Rivals in the City, I read aloud a scene that takes place in front of Newgate Prison. The year is 1860. A wooden scaffold has been built outside the prison gates, as it was before each public execution. The hangman, William Calcraft, is testing the gallows and trapdoor to ensure that they work. And the crowd is eagerly, boisterously, anticipating the day’s entertainment. All this is historically attested.

The public face of Victorian executions, William Calcraft (c. 1870). Image via wikipedia.

In the scene, I add a detail featuring ragged children “playing Calcraft”: taking turns pretending to be executioner and condemned. I invented this game, and have never formally researched “macabre children’s games, past and present” (although now that I’ve typed that phrase, it sounds like a fascinating topic). But the idea of the game rings true for me. Games of the imagination are how children process the world around them, and how they imbibe their culture. In my novel, the game of “Calcraft” has several functions: it’s a means of including children in the Victorian streetscape; a way of shifting and blending perspectives of the execution-day milieu; and, of course, a comment on the idea of a public execution in general.

Newgate Prison, mid-nineteenth century. Image via wikipedia.

After I’d read this scene aloud, one of my listeners expressed concern about the scene. Was it, he asked, appropriate to explore violence and death in a book that was written for children? Didn’t it glamorize violence and death, to see it represented in fiction? He was talking about the contemporary young adults to whom my book is marketed, but I wonder if the presence of children in the Newgate scene is what triggered his very real anxiety. It was an earnest question and I attempted to answer it with the seriousness it deserved. The party was hectic, though, and I compressed my response into a couple of brief points. Now, I think it’s time to answer the question more fully.

So is it, in fact, appropriate to explore death and violence in children’s literature? My first instinct at the party was to cite historical realism. During the Victorian era, people were much more pragmatic about death and suffering. Infant mortality was much higher than it is now; adult life expectancy was shorter. A death in the household also meant a corpse laid out in the parlour or spare bedroom. And in many cases, the women of the family washed and dressed that corpse themselves. The Victorians were less squeamish about death in general. People didn’t spay or neuter their pets; they simply drowned the unwanted litters. In Wuthering Heights, Hareton Earnshaw famously “hang[s] a litter of puppies from the chair-back in the doorway”. The shocking part of the scene is not the puppies’ deaths, but the fact that their suffering is a form of entertainment for Hareton. But remember: in Emily Brontë’s vision, even Hareton Earnshaw, Animal Sadist, is redeemable. With Cathy Linton’s love and support, it becomes possible to imagine a somewhat happy ending for Wuthering Heights.

Still, the defense of historical realism only takes us so far. After all, history contains an endless amount of truly gruesome detail. How do we decide which of those bits belong in historical fiction for young people? Let’s go back to human developmental principles. Children learn about death in bits and fragments, starting in toddlerhood. By the time they are eight years old, they are “consistent in showing adult ideas of death”. So the idea of death – with variations according to age and circumstance – is a normal part of children’s understanding. I’d go a step further, here: if a novel like Rivals in the City deliberately downplays the existence of death, it’s insulting the intelligence of its readers.

Knowing this, perhaps we can agree to acknowledge historically realistic deaths. But what about violence, and the much-feared “glamorization” of violence? Once again, let’s think about real, present-day children. Children understand violence because they are human beings. They negotiate conflict from toddlerhood. They can act violently towards others. They hear about violence on the news. They see instances of injustice all around them. The real question here is, What do they do with all this experience and all this unformed knowledge?

At this point, we must return to the specific scene or image that prompts the question. Is it an image or description of violence on the news, presented without context or consequence? I imagine that would be haunting, confusing, and possibly traumatic. Is it a video game, in which the hero-player is rewarded for acts of violence? In that case, I see how that trivializes the gravity of violent acts. In my novel, however, the threat of violence is mediated by a heroine, Mary Quinn. She is a former victim of violence who understands its impact. She has strong feelings about the uses and abuses of power. She offers readers a thoughtful perspective on the violence of her culture, and how to resist it.

If anything, I’d argue that this kind of ethically grounded violence is essential to children’s literature, and to the project of learning about the world and about oneself. I’m proud to be part of a long tradition of children’s authors who imagine the world as fully as possible, as humanly as possible, as respectfully as possible.

April 28, 2015

Well hello, spring.

So, it’s been winter in Kingston for about a hundred years. A few weeks ago, we had a teasing preview of spring followed by an interlude with some ice pellets that I’d rather not discuss. But now, at long last, spring is here.

We are now so confident of spring’s reality that we cleaned out the shed, changed over our winter tires, and tidied our compost pile to really honour the season. And last week, this absolutely magical fairy garden appeared at my daughter’s preschool.

Isn’t it amazing? It was made by a ridiculously talented parent.

Other spring-like things in our lives…

The appearance of scylla (amongst the goutweed. The Battle Against the Goutweed continues.)

We started some seeds about a week ago, and on Sunday morning woke up to this sign on our bedroom door:

It’s true, too. Just look at them. Beans are infamous troublemakers.

Even the tomato sprouts look cheeky.

And that’s how my week went. How about yours? How are you enjoying the season?

P. S. I scheduled this blog post, logged into Twitter and found another sign of spring!

Park staff are reporting that Moose watching season has arrived! Many sightings along Highway 60 this morning. pic.twitter.com/tBlcZhD9H8

— Algonquin Park (@Algonquin_PP) April 28, 2015

April 21, 2015

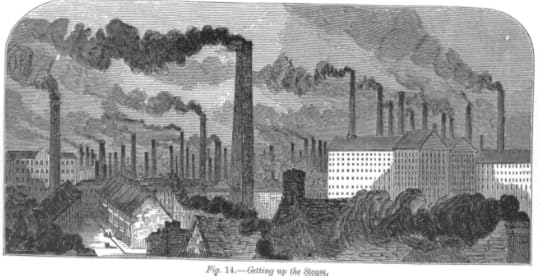

We are still the Victorians

Hello, friends. Today is Earth Day – a useful time to reflect upon what our environment is like, what might happen to our world in the future, and how things used to be. As you know, I think we’re a lot more like the Victorians than we’d prefer to believe. It’s so comforting to view them as boring, prudish, ignorant dinosaurs. It’s so flattering to congratulate ourselves upon how much we’ve changed and how modern we are. But I’m here, once again, to argue that we are much more like the Victorians than we might think.

image via victorianlondon.org

I’ve written in the past about the Great Stink of 1858, which I chose as the backdrop for A Spy in the House. It’s satisfyingly revolting to think about it – all that sewage and waste in the Thames! – and I, like most people, am really glad we don’t live that way anymore. But the Great Stink of 1858 was also a major turning point. That summer, the citizens of London learned that they couldn’t expect the river to absorb all their waste and pollution. They were forced to build modern sewers, to reconsider the amount of waste produced by factories and, above all, to change their ways. Sound familiar? As we confront our own ongoing environmental crises – oil spills, climate change, flame retardants in our water and soil – we’d do well to address our problems as directly and effectively as Londoners have done, over the last 150 years. After all there are, once again, fish swimming in the Thames.

It’s also tempting to refer to “the Victorians” as a huge, undifferentiated group. (I do it all the time here on the blog, for the sake of convenience.) But we should remember that there were Victorian environmentalists, as well. They were outnumbered by industralists, of course, much as they are now. Still, here is the future poet A. E. Housman describing a lecture he attended in 1877, as an undergraduate at Oxford. The lecturer was the art critic John Ruskin:

This afternoon Ruskin gave us a great outburst against modern times. He had got a picture of Turner‘s, framed and glassed, representing Leicester and the Abbey in the distance at sunset, over a river. He read the account of Wolsey’s death out of Henry VIII. Then he pointed to the picture as representing Leicester when Turner had drawn it. Then he said, “You, if you like, may go to Leicester to see what it is like now. I never shall. But I can make a pretty good guess.” Then he caught up a paintbrush. “These stepping-stones of course have been done away with, and are replaced by a be-au-tiful iron bridge.” Then he dashed in the iron bridge on the glass of the picture. “The colour of the stream is supplied on one side by the indigo factory.” Forthwith one side of the stream became indigo. “On the other side by the soap factory.” Soap dashed in. “They mix in the middle — like curds,” he said, working them together with a sort of malicious deliberation. “This field, over which you see the sun setting behind the abbey, is not occupied in a proper manner.” Then there went a flame of scarlet across the picture, which developed itself into windows and roofs and red brick, and rushed up into a chimney. “The atmosphere is supplied — thus!” A puff and cloud of smoke all over Turner’s sky: and then the brush thrown down, and Ruskin confronting modern civilisation amidst a tempest of applause, which he always elicits now, as he has this term become immensely popular, his lectures being crowded, whereas of old he used to prophesy to empty benches. (quotation from Norman Page’s A. E. Housman: A Critical Biography, via the Victorian Web)

Despite Housman’s dismissive tone (“a great outburst against modern times”), he does suggest that, in 1877, Ruskin had caught the prevailing mood. The undergraduates “crowding” his highly emotional lectures are not so different from the curious, critical-thinking young people of 2015 wondering what their contribution to the world will be.

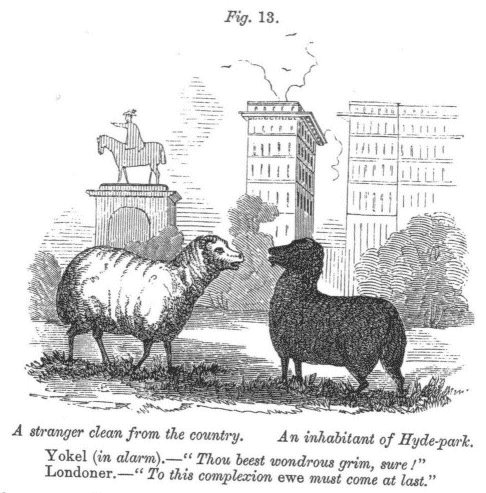

And, as this cartoon shows, Victorians got it: London was filthy.

image via victorianlondon.org

Despite the clean-up of the past 150 years, it still is. Today, if you walk past Coram’s Fields, you can see sheep living in the heart of Bloomsbury and they are, indeed, quite dingy with accumulated soot. As we think about Earth Day and what lies ahead, let’s do so knowing what changes are possible, how much change is yet to come, and how close we are to our Victorian roots.

April 14, 2015

Note to self

Hello, friends. Sometimes, when it comes to organization and work habits, I am a very slow learner. I’ve blogged before about learning to be my own good boss, and most of those lessons have stuck. Three months after starting my bullet journal, I’m still very happy using it as a system. Still, the really obvious things often elude me.

Until recently, one of my great frustrations was not being able to work effectively at home. Some days, between dropping off and picking up small children, I have a 3-hour work slot. On those days, I walk straight downtown to a café, order a coffee, and write about a thousand words with very little fuss. On other days, I have a 5- or 6-hour stretch at home. You’d think I could accomplish even more, given the extra time, but those tend to be the days that I am less productive.

You see, on those longer work days, I tend to come home, clear away the morning chaos, throw in a load of laundry, prep dinner, make some phone calls, answer email, and check my favourite blogs. The error seems so obvious, when summarized like this. Basically, I am allowing myself to be distracted by domestic responsibilities. (Domestic labour is the very definition of tyranny: no matter how hard you work, there is always more to do.) Perhaps the most wasteful part of my distraction is that I’m not using my real work space: my delightful, peaceful, warm shed.

That changed this week. Yesterday, before heading out the door with the family, I left my laptop, notebook, and mug of coffee by the door. When I came back from the school run, I performed the most critical act of the day: I did not take off my shoes. Instead, I tiptoed into the kitchen, microwaved my coffee, and fled to the shed.

Result? Efficient bliss. I cranked out 1000 words in just over 2 hours, came inside and practised yoga, then had time to wash salad greens for lunch. After lunch, I critiqued the first three chapters of Stephanie Burgis’s dragons-and-chocolate MG novel (it’s FANTASTIC! You will love it, world!) and caught up on email before heading out to pick up the children.

Lesson learned: for me, writing is all about disconnecting both from domestic duties and from the internet. And, of course, keeping my shoes on.

Readers: what techniques do you use to trick yourself into work? Are you one of those superhumans who can tweet while writing?

April 7, 2015

Adventures in author signings

Hello, friends. This past weekend, I went to Belleville to meet E. K. Johnston. She and I have been friendly on Twitter for a few years, and I became a raving fan of hers as soon as I read her debut novel, The Story of Owen. The Story of Owen, which is shortlisted for an LA Times Book Award, is about dragon slayers in small-town Ontario. It is hilarious and heartbreaking and sly and insane in all the best ways, and it’s also about music, storytelling, and courage. Can you tell that I adore it and its sequel, Prairie Fire? So when Kate asked if I wanted to do a signing, I shrieked, “YESSSSSSS!” and hied myself to Belleville, Ontario.

Ali, who manages the Chapters bookstore in Belleville, was so well organized. She had all our books set up on a stand-alone rack, flanked with tables and chairs. She had an array of pens. She had alerted her staff, some of whom came in on their day off to say hello. The whole afternoon was an object lesson in How to Host Signings.

And you know who came as a last-minute surprise guest? ERIN BOW, that’s who!

From left to right: Erin, me, Kate (photo by Ali of Chapters Belleville)

Erin’s debut novel, Plain Kate, won the TD Canadian Children’s Literature Award; her second novel, Sorrow’s Knot, won the Monica Hughes Award for Science Fiction and Fantasy. Erin is also a physicist-turned-poet. (Nope, not intimidating AT ALL.) And her beautiful, merciless novels make me weep until I’m soggy. I love them, and I aspire one day to write as well as she does.

So this was going to be a quick, celebratory blog post about the wonderful afternoon we had, the books we sold, the fascinating people we met (including a woman called Linda who hand-feeds cougars), and how much I learned from Erin and Kate about the Art of the Signing. They were funny, generous and gracious, and I want to be more like them.

And then, just today, I spotted a blog post by Kate:

WHAT? I had to click to make sure it was the same event I was at. And then I remembered the start of this conversation, reported by Kate:

A man approached the table. “You wrote these books?” he said. “Tell me about them.” So I did. I launched into my pitch, and got about halfway through. Then he held up his hand. “I’m going to stop you there,” he said. “I don’t read books. I just like to talk to people who do, because I don’t understand how they work.”

Right after he declared, “I don’t read books”, I (Ying) made a joke: “Yet here you are!” I said, loudly, gesturing at the books all around us. He ignored me, and I listened for only a couple of seconds longer before turning away. I left the scene because I’m not in the habit of cultivating the boastful, the non-readers. Neither do I listen attentively to those who ignore me.

After reading Kate’s post, however, I really wish I’d stayed in the conversation. This is what happened next:

Somehow, I ended up telling the guy that I am an archaeologist. “Why aren’t you out digging holes?” he asked. I don’t tell him that archaeologists don’t dig holes. I don’t tell him that it’s still too cold for real field work. I don’t tell him I’m not that kind of archaeologist. No, he’d made me angry, so I waved my education in his face, and told him that I have a masters in forensic archaeology and crime scene investigation.

“That’s kind of gross, eh?” he said. “Yes,” I said. Because sometimes it is.

“Well, I wouldn’t date you,” he said.

We could spend a very long time enumerating the problems with that statement, with the illogical turn the dialogue took. I won’t do it here, because Kate has already done so.

What I want to add is that I’ve now learned something else: when someone instantly flags himself as an attention-seeker (as this person did straightaway), I need to keep half an ear on the conversation. I need to stay present, as a conversational ally.

I know Kate doesn’t need protecting. She handled herself with professional sangfroid – so much so that I didn’t realize what had gone down until I read about it on the internet. But I could have jumped in. Things I could and should have said, as a semi-bystander:

“What does that have to do with anything?”

“That was inappropriate.”

“You need to leave now.”

I’m going to remember this incident. I’m going to practise those lines. And I’m going to lovingly teach every young person in my life that a) the world is not about them, and b) the golden rule.

I’m sorry I didn’t have your back there, Kate. Next time, I will.

March 31, 2015

The Victorian tattoo

Hello, friends. Today is April Fool’s Day and I feel a certain amount of not-so-subtle cultural pressure to write a gag post. I believe I ought to document a Shocking Truth about the Victorians, or similar, which I later reveal as – surprise! – a prank. Joke’s on you, sssssuckers.

However, I’ve always felt a strange resentment of April Fool’s jokes and, for that matter, practical jokes in general. (Practical jokes rely on a few people being insiders, and laughing, while others are outsiders, and laughed at.) Also, our images and preconceptions about the Victorians are crude and hazy enough that I don’t think we need to cloud the atmosphere any further. So today, I’m going to write about something that sounds like it should be an April Fool’s Day gag, but isn’t. I’m going to write about Victorian tattoos.

In Rivals in the City, James jokes about body art: “‘Perhaps I’ll have your name tattooed on my arm so there’s no doubt as to whom I belong’, he said, tucking her hand into the crook of his elbow and resuming their steady walking pace. ‘What would you say to your initials in Gothic letters, surrounded by scrolls and hearts?'” I loved being able to include this moment of dialogue because it’s such a familiar cultural motif for us now. It’s another way of bringing the Victorians closer to us, one of the projects at the heart of my fiction. But it’s also rooted in a fairly well-documented tradition.

There are brief mentions of tattoos in Victorian literature. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, Sybil Vane’s brother, James, is identifiable as a sailor because of his tattoos. I believe Sherlock Holmes notices and assigns tattoos the same kind of cultural value. According to wikipedia, it was during Captain James Cook’s voyages to Polynesia from the 1760s to the 1780s that the idea of tattoo (from the Tahition word, tatau) was introduced into English culture.

Apparently, the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, a member of Cook’s expedition, came back to England with a tattoo. (portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1773)

By the mid-nineteenth century, tattoos were firmly established as the domain of seamen and soldiers – working-class Englishmen who had travelled widely and come into direct contact with tattoo culture.

Tattoos, however, were about to make an interesting social transition. In 1862, when the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) toured the Middle East, he acquired a tattoo of the Jerusalem Cross.

The Prince of Wales in Constantinople at the end of his Grand Tour (1862). Somewhere on his body, there is a fresh tattoo. (image via the Royal Collection)

By 1870, the trend had spread not only amongst the English aristocracy, but into the courts of Russia, Germany and Spain. And beginning in the 1880s, upper-class women also began to sport discreet tattoos. One of the most celebrated was Lady Randolph Churchill, who had a “dainty” and “elaborate” tattoo of a serpent entwining her left wrist.

Lady Randolph Churchill, with her signature bracelet. (image via NYPL)

She frequently covered it with bracelets, but it was described in the New York Times in 1906. Tattoos were fashionable enough that Country Life magazine featured them in an article dated 27 January, 1900 – as if to kick off the new century. As you might expect from Country Life, it described “one of the most popular Masters of Foxhounds in England” who had “tally-ho!” tattooed on his forearm along with a fox’s head and brush and a hunting crop.

Like all fashion trends, however, tattoos were fairly swiftly brought down by mass imitation.

Nora Hildebrandt claimed that she was forced by Indians to receive hundreds of tattoos. The truth was more mundane: her father was a tattoo artist. (image via the Human Marvels)

Once performers like Nora Hildebrandt began displaying her hundreds of tattoos for the horror and delectation of the masses (she travelled as part of P. T. Barnum’s American circus), aristocrats promptly lost interest in tattoo art.

I haven’t. I’ve always been intrigued by the idea of a tattoo, yet never been able to choose a single motif or image that I’d want to wear on my body forever. In the meantime, I’ll keep reading. May I suggest Margot Mifflin’s Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo? To start you off, there are some amazing images pulled from Mifflin’s book right here.

March 24, 2015

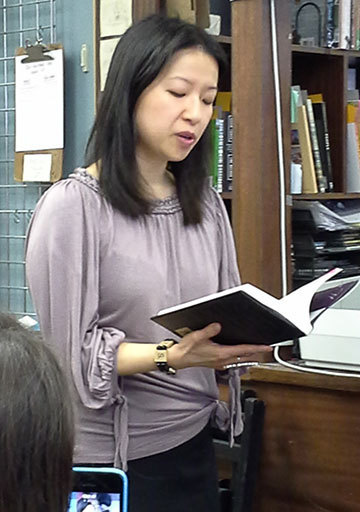

Rivals in the City: the launch party

Hello, friends. It’s March, which in our family tradition means that we’ve all fallen to a succession of viruses. There’s something about pausing for March Break that seems to invite All the Germs to trample our immune systems, and this year is no exception.

Happily, I remembered that I haven’t yet posted photos from my recent launch party. So while I currently feel like the punchline of a Kate Beaton cartoon, here are some shots from a livelier day. All photos were taken by my friend, Christine Fader. Thank you, Chris!

Chris is a strong believer in the importance of matching one’s book cover. She thoroughly approved of my (accidental) colour-coordination.

Thank you VERY much to everyone who came out to celebrate with me! You all made it a terrific and busy afternoon, and I’m so grateful for your support.

March 17, 2015

The Singapore Grip

Hello, friends. A few weeks ago, my friend Mary Alice Downie recommended to me a novel I’d never heard of, by a novelist whose name was completely new to me. It was The Singapore Grip, by J. G. Farrell.

Cover of the first edition, published 1978 by Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

My total ignorance of Farrell is all the more surprising because I hold graduate degrees in Dead White Men. Farrell, an Anglo-Irish novelist who won the Booker Prize in 1973 and drowned, aged 44, in 1979, is exactly the kind of person I ought to have studied – or at least heard mentioned in passing.

My sense of astonishment only intensified when I got my hands on a copy and read the astounding, authoritative first pages. Since then, I’ve been trying to understand how Farrell creates such a wholly absorbing atmosphere, and how his narrative voice works to such extraordinary effect. The voice in these first pages is the novelistic equivalent of the Ancient Mariner: Farrell seems to lean out of the pages, thread his finger through your buttonhole, and address to you with a “glittering eye”. About the early days of Singapore:

If you were merely a visitor, a sailor, say, in those years before the war… you would have gone to drink and dance at one of the amusement parks, perhaps even at The Great World itself, whose dance-hall, a vast, echoing barn of a place, had for many years entertained lonely sailors like yourself. There, for twenty-five cents, you could dance with the most beautiful taxi-girls in the East, listen to the loudest bands and admire the glorious dragons painted on the walls… There, too, when you staggered outside into the sweltering night, you would have been able to inhale that incomparable smell of incense, of warm skin, of meat cooking in coconut oil, of money and frangipani, and hair-oil and lust and sandalwood and heaven knows what, a perfume like the breath of life itself.

See what I mean? It’s an important reminder that historical novelists seek to evoke all the senses, but Farrell seems to go above and beyond. This kind of bursting abundance happens with his research, too. To give just one example, there’s a minor comic scene in which a character is on the phone, taking notes on how to embalm a corpse. It’s a throwaway moment, a one-sided dialogue that occurs simultaneously with another very different conversation, but Farrell absolutely goes for it:

“D’you mind if we just go over the sites of injection once more,” cried Dr Brownley in a voice of despair. “No, operator, this is an important matter, a matter of life and death. I’m a doctor, will you kindly get off the line please. Now, fluid equal to fifteen per cent of body weight into the arterial system? 450 cc to a pound, yes, I’ve got that. Two per cent body weight to be injected into each femoral artery towards the toes. One per cent into each brachial artery towards the fingers, yes. One common carotid artery towards head with two per cent. Inject same carotid towards heart with seven per cent. What happens, though, if the blood in the artery has clotted, as I’m afraid it might have by now, and you can’t force the fluid in? Wait a moment, I’m trying to note it down, yes… the extremity should be wrapped in cotton wool soaked in the fluid and then bandaged… and you keep on soaking the cotton at intervals. Good. Another thing I want to know is whether one has to inject fluid into the thoracic and abdominal cavities?”

Maybe what I loved the most was this kind of ferocious excess, which extends to Farrell’s social panorama of Singapore. He’s interested not only in the rich and powerful (which, in 1941, means English plutocrats and colonial administrators), but the displaced (a French diplomat who escapes from Vietnam with, literally, just clothes on his back; a half-Russian, half-Chinese woman blacklisted because of her Communist connections) and the poor ( thousands of Chinese families who lived on boats along the river; the servant class). At one point, Farrell even takes you into the mind of a terrified Japanese private going into battle.

Cover of the 2005 edition from the New York Review Books Classics.

There’s a very casual brutality at work in the novel, which seems entirely appropriate given its subject. The closest thing it has to a protagonist is the not-so-young but idealistic Matthew Webb, who stumbles into Singapore in late 1941 and tries to find his moral bearings. Matthew is both sympathetic but infuriating, full of noble impulses and thoughtless cruelties. Despite his high-minded ideals, he doesn’t actually do much; despite his wealth, he has almost no impact. He’s a perfect Everyman for Farrell’s modern morality play.

As is obvious by now, I love and admire this novel. I also need to re-read it, in hopes of better understanding how it works. I’ll leave you today with Farrell’s conclusion. After 553 pages of suffering, injustice, black comedy, blighted hopes, hypocrisy, racism, and impotent rage, he leaves you thus:

In any case, there is really nothing more to be said. And so, if you have been reading in a deck-chair on the lawn, it is time to go inside and make the tea. And if you have been reading in bed, why, it is time to put out the light now and go to sleep. Tomorrow is another day, as they say, as they say.

So… what are you reading right now, friends?

March 9, 2015

Writing Diversity in Dialogue

Hello, friends. I hope you have a celebratory libation in hand. I certainly do, because today is Rivals in the City‘s birthday! As many of you know, this has been a long time coming, and there were definitely times when I feared it would never happen at all. But March 10 is here, and Rivals is now on sale in bookstores across Canada and the U. S.

Despite the jubilation, this is also a bittersweet day for me. The publication of Rivals also marks the end of the Agency quartet – the last Mary Quinn adventure, the last time I write dialogue between Mary and James, and probably my last romp through London, 1858-1860.

Despite the jubilation, this is also a bittersweet day for me. The publication of Rivals also marks the end of the Agency quartet – the last Mary Quinn adventure, the last time I write dialogue between Mary and James, and probably my last romp through London, 1858-1860.

Don’t worry: I’m not finished writing novels! I’m just ready to try a new setting. Despite the fact that I’m eager for change, though, it’s hard to leave this world behind. It feels like a second home to me (a family cottage?), and I’ll miss it dearly.

To mark this special week, I wrote a guest post called “Writing Diversity in Dialogue” for Cindy Pon and Malinda Lo’s very fine site, Diversity in YA. If you read it first there and are just finding your way here, welcome! I’m re-posting it here this week, though, because there’s no comments section at DiYA, and my desire is to start a conversation about this sticky subject. So please, let me know what you think, either in the comments below or on Twitter (I’m @yinglee). I’d love to discuss this to the next stage in good company.

Writing Diversity in Dialogue

One of the delights of the written word is the power – in fact, the necessity – of creating your own mental pictures and soundtrack. Only you know just what the heroine looks like when she’s angry; only you know the precise music of her nemesis laughing. Setting plays a huge role, too: contemporary America vs. medieval France vs. a planet far, far away. As readers, we are our own casting directors, cinematographers, and composers. I’m here today to argue that we should be our own dialogue coaches, too.

As a genre, historical fiction – which I love, and which I write – is prone to spelling out accents. Often, it’s not enough to mention in passing that a character is a stableboy or a visiting German aristocrat; the characters’ words are spelled out so that we can see, on the page, just how outlandish their pronunciation is. And that’s not all. The real problem is that historical fiction is especially prone to spelling out lower-class accents.

See the bias here? Everybody has an accent; that much is obvious. But in novels where lower-class accents are spelled out, the upper-class accents are rendered in standard English spelling. The not-so-subtle subtext is that upper-class accents are “normal”, while lower-class accents deviate from an invisible, correct norm. Add to this the fact that working-class accents are most frequently used to provide comic relief or create pathos, and what we have is proud and unexamined social snobbery written openly on the page. We should be embarrassed. We should repudiate this. We should complain, bitterly, so that writers and editors re-think assumptions about class, accent, and the ways we report speech.

When I wrote the Agency novels, I solved the problem by representing dialect (irregular grammar) but not accent. I might write a character who says, “I don’t know who done it.” I might even write, “Dunno” instead of “Don’t know,” on the grounds that everybody, across the social spectrum, uses contractions in speech. But I assume that my readers can imagine what “I don’t know who done it” might sound like, spoken aloud. I won’t write, “I daown’t knaow ‘oo dunnit!” It’s patronizing, it’s ugly, and it’s an invitation to readers to feel superior to that character.

But whether they were mudlarks or monarchs, all these characters of mine were native speakers of English. When writing Rivals in the City, I found that I had a fresh problem: how to write dialogue for a character who speaks imperfect English. A character, in fact, who spoke only Chinese until a couple of years prior to the action of the novel, and who speaks with a distinct Chinese accent.

I wasn’t going to fall into the trap of spelling out his pronunciation. Still, I felt stuck as to how to convey his accent. Stereotypes of Asian accents in English are usually patronizing and ugly. While French accents are heard as charming, and British accents register as classy, Asian accents are fodder for the unfunniest kinds of jokes. How many times have you heard a French or British person congratulated on speaking “without an accent”? Yeah. Asian accents are the stableboys of the accent hierarchy.

In the end, after a lot of deliberation, I wrote this Chinese character’s dialogue as I would that of any other. His vocabulary is more limited, because he’s relatively new to the language. Figures of speech perplex him. But for me, the clearest and most respectful way of signaling his difference was in giving him words, hearing him speak, and having him articulate his confusion and discomfort with London life in the year 1860. I think that was enough.

I’m curious, though: have you tried or run across other respectful, effective strategies for signaling difference through accent? I’d love to hear them. With any luck – because we’re going to keep reading and writing about diverse casts of characters, right? – this problem will be with us for a long time yet.

(This post was also published earlier this week at Diversity in YA.)

March 3, 2015

Author Math

One of the things I find consistently surprising in historical fiction is how very long it takes to get from one place to another. The Agency novels are set in London between 1858 and 1860. They’re too urban to make use of the railways that criss-crossed England and a shade too early for the first intra-city underground trains (the steam-powered Metropolitan Railway opened in 1863). Most of the travel in my books takes place either on foot or by horse-power: carriages, cabs, and of course, simply riding on horseback. By 1858, there were also horse-drawn omnibuses that, like our present-day buses, plied regular routes through the city.

An early omnibus (image from wikipedia)

The climax of Rivals in the City features a fair amount of running around between locations in central London. One of the first things I did when plotting it was create a chart showing the different sites, the distances between them, and how long it would take to move from one point to another. In order not to spoil the plot (Rivals will be published next week in the U. S. and Canada; it’s already available in the UK), I’ve renamed the locations after four of my favourite North American cities. This, of course, is a fiction upon a fiction; the real locations are London landmarks. Otherwise, here’s what my chart looks like:

Timing the final action

I assumed an average running speed of about 6 miles/10 km per hour – a pretty fast clip for a woman burdened with heavy clothes on slick, inconsistently paved, and poorly lit urban streets (it’s after dark). But I’m talking about the women of the Agency, an elite detective firm. Not only are they are in excellent physical form, they are responding to an emergency.

I assumed an average running speed of about 6 miles/10 km per hour – a pretty fast clip for a woman burdened with heavy clothes on slick, inconsistently paved, and poorly lit urban streets (it’s after dark). But I’m talking about the women of the Agency, an elite detective firm. Not only are they are in excellent physical form, they are responding to an emergency.

I assumed a horse trot of 7-8 mph, since poor road quality and night-time visibility again make it impossible to canter. With horseback, I also needed to allow tie-up time and the need to rest or change horses. Riding turned out to be not much faster than running, but riding made it possible for a character to arrive at an important location looking respectable.

As it worked out, the time elapsed for a series of important messages to be relayed was:

– 57 minutes: for a character to run from Vancouver to Toronto and back again

– 41 minutes, plus delays while tying-up a horse: for a character to ride from Toronto to New York, and then from New York to Montreal

– 30 to 35 minutes, plus time for marshalling and instructions: for a large group to walk quickly from Montreal to Vancouver

This left me with a space of 2 ¼ hours, the minimum period of time my heroine, Mary Quinn, would be alone in “Vancouver” after sounding the alarm. It turned out to be the perfect window of time to allow her to take action, imperil herself, yet receive help at just the right moment.

This left me with a space of 2 ¼ hours, the minimum period of time my heroine, Mary Quinn, would be alone in “Vancouver” after sounding the alarm. It turned out to be the perfect window of time to allow her to take action, imperil herself, yet receive help at just the right moment.

I love this kind of concrete plotting, and wonder if any of you do the same. How do you work out timelines, near-misses, and rescues?

(This post was also published yesterday at The History Girls.)