Matthew Dicks's Blog, page 611

May 25, 2011

Meteorological influences on a book review

A while back, Washington Post fiction critic extraordinaire Ron Charles tweeted:

Does being stuck inside writing a review on this gorgeous day make me even more annoyed with this tedious novel?

I was never able to determine the book to which he was referencing, but the comment It left me wondering if a critic's personal circumstances might impact his opinion of a book.

Did the fine weather and his unfortunate confinement impact Charles' review of the book?

Probably not.

But are their more likely circumstances in which a critic's opinion can be influenced?

For example, what about the previous novel that the critic has read? If he has just finished reading a real clunker, does that give the next book a slight leg-up?

And conversely, what if the critic has just read what he considers to be the book of the decade? Will this influence his opinion of the next book he reviews? Could the next book ever measure up to the previous book, and if not, will the review be inherently, if not purposefully, less favorable?

The list of potential influencers is endless.

Did the critic and his wife engage in verbal fisticuffs just prior to sitting down to read the book?

Were the kids' report cards uncommonly glowing?

Was dinner a disappointment?

Did the critic just have sex?

Did the critic's iPhone refuse to sync?

Had the critic recently lost a lot of weight through minimal effort?

Was the local 7-11 out of Chunky Monkey and Cherry Garcia?

Was the critic drunk?

Was his back sore?

Was a recent performance review less than favorable?

Does the cover art on the book remind the critic of the girl in high school who dumped him for his step-brother?

Did the critic's dog die?

While I like to think that all book critics are impartial and souls, perfectly capable of excluding their personal successes and disappointments from their work day, it's probably not possible.

As impartial as they may be, a personal crisis tends to weave its way into the fabric of our lives, whether we like it or not.

So wonder how often a critic's opinion of a book is slightly shifted by circumstance.

Can the weather or a technological snafu or the death of a pet change a review for better or worse?

Maybe.

And so I give my my author's prayer:

When it comes time to review my next book, may all the fine critics of the world be the slightly drunk, suddenly thin parents of straight A students who have been away at camp for a month, allowing critic and spouse to eat Chunky Money ice cream and have sex on the dining room table after a more-than-satisfying late-night dinner.

May 24, 2011

I have never been treated by an OB/GYN but I have an opinion on the subject nonetheless

Admittedly I have almost no experience when it comes to OB/GYNs.

Unfortunately that will not stop me from commenting on a piece in Slate that criticizes OB/GYN practices in Florida for establishing 200 pound weight limits for their patients.

When I first read the headline, I was a little shocked. I thought, "Are these doctors turning these women away based upon their physical appearance? And do these doctors care that much about their patients' physical appearance?"

If so, the ick-factor of the OB/GYN field just increased ten-fold.

But then I read the paragraph explaining the rationale for the weight restrictions, which included author Anna Resiman's counterarguments:

Some of the doctors interviewed in the article opted not to care for obese women because of inadequate equipment. That's pathetic: As I've said here before , they should buy larger exam tables, longer speculums, and bigger blood pressure cuffs, and do their best. Another reason for the ban, according to one of the office managers: The doctors weren't "experts in obesity" and didn't want to have to send patients to specialists if problems occurred. My take: Doctors should be adept at caring for patients of all sizes. Gynecologists don't only do pelvic exams; a big part of their job is counseling. There's no reason any should shy away from counseling overweight women, whether that entails diet and exercise recommendations or referrals to dieticians and bariatric surgeons. One of the doctors rationalized his decision as a way to decrease potential surgical complications and lawsuits; while this might make his work easier, what if all doctors in this part of Florida followed suit?

Let's look at Reisman's counter-arguments in order.

1. Doctors claim that they lack the equipment to deal with women over 200 pounds.

Reisman's response: "…they should buy larger exam tables, longer speculums, and bigger blood pressure cuffs, and do their best."

Really? Are doctors expected to purchase enough equipment to handle every patient who could potentially walk in the door? Does Reisman think that these doctors have piles on money in their closets, ready to be spent on whatever piece of equipment they need, regardless of the fiscal sensibility of purchasing the equipment?

Isn't a doctor permitted to determine how often he or she might use a piece of equipment and then determine if the purchase is cost-effective? They are running a business, and it would seem to me that "they should just buy more stuff" implies that business decisions should play no role in medicine.

Perhaps in an ideal world, but rather naïve in this one, I think.

2. The doctors weren't "experts in obesity" and didn't want to have to send patients to specialists if problems occurred.

Reisman's response: "Doctors should be adept at caring for patients of all sizes."

Really? Is medicine truly a one-size-fits-all model?

Is it unreasonable for a doctor to admit to not knowing everything?

Is it unreasonable to think that the needs of a 200 pound woman could be vastly different than the needs of 130 pound woman? Do we really want to tell doctors that they should know everything about their potential patients, regardless of their physical attributes, and not rely on experts in the field who specialize on particular patient attributes?

As a teacher, should I be expected to teach kindergarteners and high school seniors with the same level of skill? Like doctors, should teachers also be adept at teaching students of all sizes? If not, why?

As a writer, should I be expected to be able to write a textbook and a technical manual with the same skill as I write a novel? If I can write 120,00 words of fiction at a time, should I also be able to write a 5,000 word car manual?

The idea that a doctor should simply be able to treat all patients regardless of their physical differences is absurd.

Reisman adds:

There's no reason any should shy away from counseling overweight women, whether that entails diet and exercise recommendations or referrals to dieticians and bariatric surgeons.

Sure there is. What if a doctor is not skilled or adept at counseling overweight women on diet and exercise? Do we really expect the doctor who specializes in obstetrics and gynecology to also be an expert on nutrition, exercise, weigh management, and more? If so, why do we have doctors who specialize in these fields already? Must we force doctors to become experts in multiple disciplines in order to cater to every possible patient who walks in the door?

3. One of the doctors rationalized his decision as a way to decrease potential surgical complications and lawsuits.

Reisman's response: "…what if all doctors in this part of Florida followed suit?

Three points here:

First, did Reisman really just cite one doctor as an indicator of the industry's rationale?

Second, if the decision to set a weight limit on patients does in fact reduce surgical complications and lawsuits, can we fault a doctor for making a valid business decision in order to remain profitable?

And doesn't the increase of surgical complications for some doctors imply the need for expertise in this field?

Do 200 pound women want to be treated by an OB/GYN who experiences higher rates of surgical complications?

But it's the last part of the sentence that contains the great degree of stupidity:

"…what if all doctors in this part of Florida followed suit?"

Ah, yes. The doomsday scenario. Always the sign of a rhetorical mastermind.

Does anyone believe in a free market economy that there won't be doctors willing to treat the exploding population of obese patients in our country?

Does Reisman expect the reader to foresee a day when it will be impossible for a obese women to find an OB/GYN willing to treat her?

Or is it more reasonable to foresee a day in which some doctors are perfectly willing and appropriately skilled at dealing with the unique needs of an obese woman and some are not?

Unacceptable platitude #3

"That's your opinion."

For clarification, this statement, and ones similar to it, are often made after a person states an opinion in the midst of a heated argument.

For example:

"No, I think chunky monkey is a the stupidest ice cream on the planet. Strawberry is clearly the best. It's simple. It's classic. It's known by all. Sometimes it contains actual strawberries. And you're not left wondering if it's made from actual monkey bits. Strawberry rocks."

"That's your opinion, monkey-face!"

One of the nice things about learning to distinguish between fact and opinion in elementary school this that this universal knowledge base mitigates the need to say "in my opinion" after stating an opinion.

So when I say that Mariano Rivera is the best closer in baseball history or that Sarah Palin would make a frightening President or that Ranch dressing is the most vile substance known to man, we all know that these are opinions, no matter how forcefully or with how much certainty I may state them.

Yes. It's an opinion. We all know it's an opinion. We know the difference between fact and opinion.

Just like it is an opinion when I tell you that you are a moron for defining my opinion as an opinion.

Distinguishing an opinion does not qualify as a valid verbal rebuttal.

In our world, we do not need to differentiate facts and opinions as we speak.

We all just do it in our heads.

May 23, 2011

Raptured!

At least one reader decided to follow through on Wendy Clinch's Rapture idea, which makes me extremely happy considering I forgot about it completely.

I'd like to use the excuse that my daughter's great grandmother was staying with us for the weekend and we spent much of the day at the Connecticut Book Festival, listening to illustrator Wendell Minor and author Wally Lamb speak.

And while this is true, it is no excuse. That Rapture idea was brilliant, and Raptures don't come around every day.

I'll probably have to wait a least a year or two before the world ends again.

Ice cream for dinner!

That's right.

As my wife and I were finishing our walk with the dog, she turned to me and said, "How about some ice cream for dinner tonight?

She didn't have to ask twice.

And I strongly suggest that everyone try this at least once.

As adults, we sometimes forget the when-I-grow-up promises that we made to ourselves as children. The seemingly infinite possibilities that would one day come with the freedom of adulthood.

ice cream for dinner was probably a childhood promise for many of us, and for good reason.

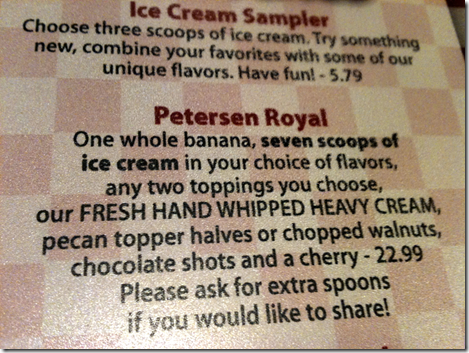

Thirty minutes later, Elysha, Clara and I were sitting in a local ice cream parlor, scanning the menu, when I came across this item:

The Petersen Royal

Please note that there is $23:00 worth of ice cream in this monster, and they suggest that you ask for extra spoons if you would like to share.

If you would like to share?

Even if the seven scoops of ice cream, the whole banana and the assorted toppings aren't enough to stop a person, isn't the $23.00 price point barrier enough in terms of trying to eat this alone?

May 22, 2011

Death to the elephants

I was teaching my students about idea generation in regards to writing, using a student-friendly version of Time magazine called Time for Kids as my source. I explained that one of the best ways to generate a writing topic is to find a piece that you find objectionable and write the counter-argument.

And if you can take a position rarely taken by others, you might really be onto something.

In order to demonstrate, I began flipping through the magazine and seeking counter arguments to the articles and the opinions presented. Eventually my eyes fell upon a piece about an elephant rescue camp in Africa.

"Here's something," I said. "The people working at this camp are trying to save elephants from extinction. But could you take the opposing position? Could you argue that elephants should be allowed to die out? After all, they are at the top of the food chain, with no natural predators, and they are not carnivores, so it's not as though they serve to control any other animal population. If elephants went extinct tomorrow, would there really be a problem?"

Now I was on a roll.

"And couldn't the money being spent keeping elephants alive be better used? Couldn't we protect an animal more vital to the food chain? Or to save human lives instead?"

The kids were now staring at me in horror.

"And besides, the dodo bird went extinct. Other than its sentimental value, has the world really suffered from its absence? And what about the passenger pigeon? Or the giant tree sloth? Or perhaps most appropriately, what about the wholly mammoth? Does the world really need the wholly mammoth? And if not, why not get rid of the elephant, too?"

Naturally, I don't believe anything I said, but I thought it was a good illustration of how a writer can adopt a contrary position for the sake idea generation, and how it is perfectly reasonable for a writer to argue a point that you don't necessary believe.

And who knows? I may not believe what I had said, but I did find myself legitimately wondering what purpose elephants serve in the food chain and how much money is spent keeping them alive.

Sometimes an academic exercise like this can yield a genuine contrarian viewpoint.

Before I was able to explain to the kids that I did not really want the elephant to go extinct and that this was simply an illustration of idea generation, one of them muttered, "And he wonders why they hate him so much."

"I was going to get to that," I said, impressed once again by a student's wisdom beyond his years.

May 21, 2011

Unprofitable near-death experiences

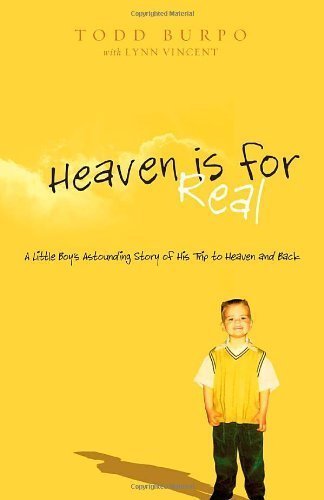

The New York Times reported that on Easter Sunday, the number one book on Amazon.com's Religion and Spirituality best-seller list was "Heaven Is for Real: A Little Boy's Astounding Story of His Trip to Heaven and Back," an account of a 4-year-old's near-death experience as dictated to his pastor father.

It turns out that near-death stories are reliable sellers. There's another book about a child's return from paradise, "The Boy Who Came Back From Heaven," just a little further down the Amazon rankings.

In fact, Amazon has a list of books that deal with near-death experiences.

For a moment, I felt a little left out. Having survived two legitimate near-death experiences (death #1 and death #2) and one that most people would characterize as close enough, I wondered if I had let an opportunity go by the wayside.

Maybe I should write a book about my experiences. After all, I'm a two-time survivor with a warm-up story to boot.

This has to be better than the unreliable ramblings of a 4-year old. Right?

Then I recalled something that a former student said to me recently. Having read an online interview with me and done some research into my life, he asked, "You really had to be brought back from the dead twice?"

"Yeah. Bee sting and car accident."

"We're talking CPR, mouth-to-mouth… everything?" he asked.

"Yup. Afraid so."

Then he paused for a moment, as if mustering the courage to ask the next question. Finally, he said, "Did you see a white light or anything like that when you died?"

"Nope."

"No sign of Heaven? Or God? Not even a little bit of light."

"Nope. Nothing."

"Damn!" he shouted, throwing his hands in the air. "I knew it!"

"No,no," I said, suddenly realizing what I had done. While I am not a believer, I don't want to spoil the belief of others on a whim. "That doesn't mean there isn't a Heaven," I added. "Maybe I just wasn't dead long enough."

"Naw," he said, resignation filling his voice. "I knew it all along."

Perhaps I need to be slightly more inspirational and uplifting if I ever hope to profit from my near-death experiences.

And maybe add a little white light.

May 20, 2011

Spared his life

We may not always like our pets, but we love them, and my daughter is probably their greatest supporter.

I think my wife would've murdered both of them by now had it not been for Clara's love for them.

Owen, our cat, especially, though now that Clara is getting older, Kaleigh is starting to make up ground in the love department.

Is this version any less likely?

My niece, Lexi, told my sister about the story of Noah's Ark today:

"It's the big ship with all the animals that Uncle Sam flew and it came down and crushed the Earth."

Not quite the version that appears in the Bible, but is it really any less likely than every species of animal voluntarily making its way to the Middle East (including penguins and polar bears, and depending upon your level of fanaticism, dinosaurs), climbing aboard a boat in just before a worldwide flood, and somehow repopulating the planet one the flood water dissipated despite the lack of genetic diversity?

I kind of like Lexi's version better.

I couldnt have said it any better, and that makes me so angry

Damn that Charles Schwab.

In commenting on how to increase employee productivity, he once said:

"The way to get things done is to stimulate competition. I do not mean in a sordid, money-getting way, but in the desire to excel."

These two sentences sum up the essence of my teaching philosophy.

That's what I do.

And Schwab's words sound so good, too. So clear and succinct.

I'm so jealous.

My quest for inclusion into Bartlett's Book of Familiar Quotations continues, but it will likely not include anything as good as Schwab's two sentence miracle.