Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 29

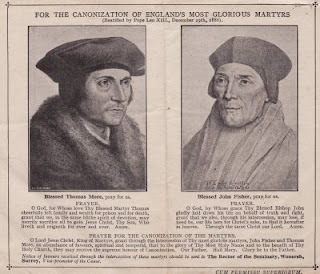

August 4, 2022

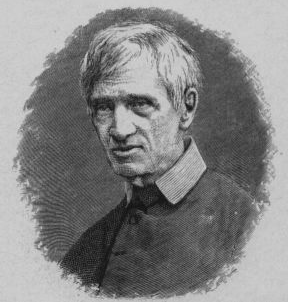

Preview: St. J.H. Newman's Anglican Reverence Toward the Blessed Virgin Mary

We're going to continue on a Marian Newman theme throughout the month of August in our Monday morning Son Rise Morning Show exchanges, so on Monday, August 8, Anna Mitchell or Matt Swaim and I will take a look at the Parochial and Plain Sermon Newman delivered on the Feast of the Annunciation in 1832, as the Vicar of St. Mary's the Virgin in Oxford.

I'll be on at my usual time, about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern.

Please listen live here on EWTN or on your local EWTN affiliate.

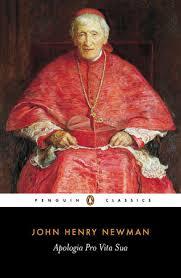

Last week I mentioned this passage from chapter four of the Apologia pro Vita Sua. Writing in 1864, Newman looks back and remembers the tug at his heart he was feeling as the Vicar of St. Mary's the Virgin and Fellow at Oriel College, founded in 1326 as "the College of the Blessed Virgin Mary":

In spite of my ingrained fears of Rome, and the decision of my reason and conscience against her usages, in spite of my affection for Oxford and Oriel, yet I had a secret longing love of Rome the Mother of English Christianity, and I had a true devotion to the Blessed Virgin, in whose College I lived, whose Altar I served, and whose Immaculate Purity I had in one of my earliest printed Sermons made much of. (p. 165)

The sermon he refers to is "The Reverence Due to the Virgin Mary", sermon 12 in Parochial and Plain Sermons, Volume 2, published in 1835.

Just a little biographical context: Newman had begun reading the Fathers of the Church systematically in 1826; he'd been Vicar of St. Mary's since 1828, and he published his first book, The Arians of the Fourth Century the same year he wrote and delivered this sermon. And, as he notes in the first chapter of the Apologia pro Vita Sua, he was influenced by his friend Richard Hurrell Froude:

It is difficult to enumerate the precise additions to my theological creed which I derived from a friend to whom I owe so much. He made me [Note 47] look with admiration towards the Church of Rome, and in the same degree to dislike the {127} Reformation. He fixed deep in me the idea of devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and he led me gradually to believe in the Real Presence.

If you've had time to the read the two sermons I highlighted last week here and in my discussion with Matt Swaim on Monday, August 1, you'll see great connections between those Catholic sermons and this Anglican sermon.

Newman begins, inspired by Luke 1:43 ("From henceforth all generations shall call me blessed."):

TODAY we celebrate the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary; when the Angel Gabriel was sent to tell her that she was to be the Mother of our Lord, and when the Holy Ghost came upon her, and overshadowed her with the power of the Highest. . . .

TODAY we celebrate the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary; when the Angel Gabriel was sent to tell her that she was to be the Mother of our Lord, and when the Holy Ghost came upon her, and overshadowed her with the power of the Highest. . . .

Her cousin Elizabeth was the next to greet her with her appropriate title. Though she was filled with the Holy Ghost at the time {128} she spake, yet, far from thinking herself by such a gift equalled to Mary, she was thereby moved to use the lowlier and more reverent language. "She spake out with a loud voice, and said, Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb. And whence is this to me, that the mother of my Lord should come to me?" ... Then she repeated, "Blessed is she that believed; for there shall be a performance of those things which were told her from the Lord." Then it was that Mary gave utterance to her feelings in the Hymn which we read in the Evening Service. (The Magnificat)

Newman introduces the image of Mary as the Second Eve and enters into the psychology of her Magnificat:

How many and complicated must they have been! In her was now to be fulfilled that promise which the world had been looking out for during thousands of years. The Seed of the woman, announced to guilty Eve, after long delay, was at length appearing upon earth, and was to be born of her. In her the destinies of the world were to be reversed, and the serpent's head bruised. On her was bestowed the greatest honour ever put upon any individual of our fallen race. God was taking upon Him her flesh, and humbling Himself to be called her offspring;—such is the deep mystery! She of course would feel her own inexpressible unworthiness; and again, her humble lot, her ignorance, her weakness in the eyes of the world. And she had moreover, we may well suppose, that purity and innocence of heart, that bright vision of faith, that confiding trust in her God, which raised all these feelings to an intensity which we, ordinary mortals, cannot understand.

With that kind of insight into human weakness Newman often demonstrates, he notes that we take the words of the Magnificat too much for granted even as we pray or chant every evening:

We cannot understand them; we repeat her hymn day after day,—yet consider for an instant in how different a mode we say it {129} from that in which she at first uttered it. We even hurry it over, and do not think of the meaning of those words which came from the most highly favoured, awfully gifted of the children of men. "My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour. For He hath regarded the low estate of His hand-maiden: for, behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. For He that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is His name. And His mercy is on them that fear Him from generation to generation."

Newman continues the theme of God's purpose in the Incarnation and His choice of a Second Eve to heal the wounds of the Fall of Adam and Eve, citing the Protoevangelium (Genesis 3:15):

I observe, that in her the curse pronounced on Eve was changed to a blessing. Eve was doomed to bear children in sorrow; but now this very dispensation, in which the token of Divine anger was conveyed, was made the means by which salvation came into the world. Christ might have descended from heaven, as He went back, and as He will come again. He might have taken on Himself a body from the ground, as Adam was given; or been formed, like Eve, in some other divinely-devised way.

But, far from this, God sent forth His Son (as St. Paul says), "made of a woman." For it has been His gracious purpose to turn all that is ours from evil to good. Had He so pleased, He might have found, when we sinned, other beings to do Him service, casting us into hell; but He purposed to save and to change us. And in like manner all that belongs to us, our reason, our affections, our pursuits, our relations in life, He {130} needs nothing put aside in His disciples, but all sanctified. Therefore, instead of sending His Son from heaven, He sent Him forth as the Son of Mary, to show that all our sorrow and all our corruption can be blessed and changed by Him. The very punishment of the fall, the very taint of birth-sin, admits of a cure by the coming of Christ.

Newman even notes that the blessedness of Mary undoes the subjugation of women after the Fall:

But there is another portion of the original punishment of woman, which may be considered as repealed when Christ came. It was said to the woman, "Thy husband shall rule over thee;" a sentence which has been strikingly fulfilled. Man has strength to conquer the thorns and thistles which the earth is cursed with, but the same strength has ever proved the fulfilment of the punishment awarded to the woman. Look abroad through the Heathen world, and see how the weaker half of mankind has everywhere been tyrannized over and debased by the strong arm of force. . . .

But when Christ came as the seed of the woman, He {131} vindicated the rights and honour of His mother. . . . "notwithstanding, she shall be saved through the Child-bearing;" [1 Tim. ii. 15.] that is, through the birth of Christ from Mary, which was a blessing, as upon all mankind, so peculiarly upon the woman. Accordingly, from that time, Marriage has not only been restored to its original dignity, but even gifted with a spiritual privilege, as the outward symbol of the heavenly union subsisting betwixt Christ and His Church.

Thus has the Blessed Virgin, in bearing our Lord, taken off or lightened the peculiar disgrace which the woman inherited for seducing Adam, sanctifying the one part of it, repealing the other.

He considers how the Scripture speak less of Mary once Jesus begins His public ministry, but he notes that the Holy Bible was inspired and written, "not to exalt this or that particular Saint, but to give glory to Almighty God. There have been thousands of holy souls in the times of which the Bible history treats, {133} whom we know nothing of, because their lives did not fall upon the line of God's public dealings with man. In Scripture we read not of all the good men who ever were, only of a few, viz. those in whom God's name was especially honoured."

Thus, as an Anglican Vicar, Newman highlights how carefully the Church of England offers reverence to the Mother of God:

Hence, following the example of Scripture, we had better only think of her with and for her Son, never separating her from Him, but using her name as a memorial of His great condescension in stooping from heaven, and not "abhorring the Virgin's womb." [Quoting the Te Deum as he does in the 1849 sermons cited last week]

And this is the rule of our own Church, which has set apart only such Festivals in honour of the Blessed Mary, as may also be Festivals in honour of our Lord; the Purification commemorating His presentation in the {136} Temple, and the Annunciation commemorating His Incarnation. And, with this caution, the thought of her may be made most profitable to our faith; for nothing is so calculated to impress on our minds that Christ is really partaker of our nature, and in all respects man, save sin only, as to associate Him with the thought of her, by whose ministration He became our brother.

In concluding his sermon, Newman applies what he's said about the Blessed Virgin Mary to himself and his congregation:

Observe the lesson which we gain for ourselves from the history of the Blessed Virgin; that the highest graces of the soul may be matured in private, and without those fierce trials to which the many are exposed in order to their sanctification. So hard are our hearts, that affliction, pain, and anxiety are sent to humble us, and dispose us towards a true faith in the heavenly word, when preached to us. Yet it is only our extreme obstinacy of unbelief which renders this chastisement necessary. The aids which God gives under the Gospel Covenant, have power to renew and purify our hearts, without uncommon providences to discipline us into receiving them. God gives His Holy Spirit to us silently; and the silent duties of every day (it may be humbly hoped) are blest to the sufficient sanctification of thousands, whom the world knows not of. The Blessed Virgin is a memorial of this; and it is consoling as well as instructive to know it.

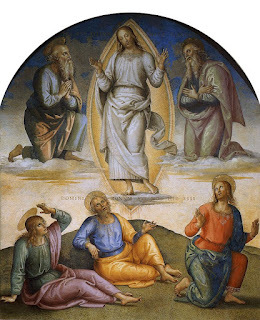

With a delicate reference to the Transfiguration (which we will celebrate tomorrow, August 6 on the First Saturday of the Month!), at end of this sermon Newman alludes to Christ's Second Coming, the End of the World, and Mary's presence on that day:

With a delicate reference to the Transfiguration (which we will celebrate tomorrow, August 6 on the First Saturday of the Month!), at end of this sermon Newman alludes to Christ's Second Coming, the End of the World, and Mary's presence on that day:The day will come at length, when our Lord and Saviour will unveil that Sacred Countenance to the whole world, which no sinner ever yet could see and live. . . . And then will be fulfilled the promise pledged to the Church on the Mount of Transfiguration. It will be "good" to be with those whose tabernacles might have been a snare to us on earth, had we been allowed to build them. We shall see our Lord, and His Blessed Mother, the Apostles and Prophets, and all those righteous men whom we now read of in history, and long to know. Then we shall be taught in those Mysteries which are now above us. In the words of the Apostle, "Beloved, now are we the sons of God, and it doth not yet appear what we shall be; but we know that, when He shall appear, we shall be like Him, for we shall see Him as He is: and every man that hath this hope in Him, purifieth himself, even as He is pure." [1 John iii. 2, 3.]

We certainly won't have time Monday morning to delve into the distinctions to be made between what Newman wrote in 1832 as an Anglican and what he wrote in 1849 as a Catholic. This one passage, which I did not quote in the sequence above (p. 136), might serve as a starting point for such a comparison:

But, further, the more we consider who St. Mary was, the more dangerous will such knowledge of her appear to be. Other saints are but influenced or inspired by Christ, and made partakers of Him mystically. But, as to St. Mary, Christ derived His manhood from her, and so had an especial unity of nature with her; and this wondrous relationship between God and man it is perhaps impossible for us to dwell much upon without some perversion of feeling. For, truly, she is raised above the condition of sinful beings, though by nature a sinner; she is brought near to God, yet is but a creature, and seems to lack her fitting place in our limited understandings, neither too high nor too low. We cannot combine, in our thought of her, all we should ascribe with all we should withhold.

Otherwise, he says very little here that any Catholic would not say about the Blessed Virgin Mary as a saint and model--but I'd say that in 1832, Newman was still leery of promoting to his Anglican congregation, not reverence toward the Mother of God, but devotion to her.

Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us!Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

Image source: (Public Domain, provided by the Cornell University Library: This image is from the Cornell University Library's The Commons Flickr stream.The Library has determined that there are no known copyright restrictions.) Oxford. University Church of Saint Mary the Virgin. Architect: Nicholas Stone. Sculpture Date: 1637. Building Date: 1280-ca. 1637. Photograph date: ca. 1865-ca. 1885.

Image source (Public Domain): The Transfiguration by Pietro Perugino, c. 1500.

July 28, 2022

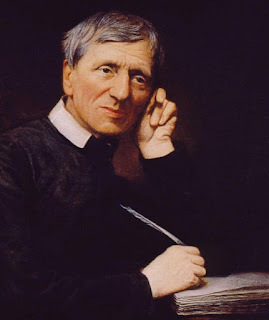

Preview: St. J.H. Newman and the Immaculate Heart of Mary

Since August is the month traditionally dedicated to devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, we thought it appropriate to continue our Monday morning Summer Newman series on the Son Rise Morning Show on August 1st with some comments about Saint John Henry Newman's devotion to Mary, the Mother of God. Either Anna Mitchell or Matt Swaim and I will discuss this topic at my usual time, about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern.

Since August is the month traditionally dedicated to devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, we thought it appropriate to continue our Monday morning Summer Newman series on the Son Rise Morning Show on August 1st with some comments about Saint John Henry Newman's devotion to Mary, the Mother of God. Either Anna Mitchell or Matt Swaim and I will discuss this topic at my usual time, about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern.Please listen live here on EWTN or on your local EWTN affiliate.

In chapter four of the Apologia pro Vita Sua, Newman remembers the tug at his heart he was feeling as the Vicar of St. Mary's the Virgin and Fellow at Oriel College, founded in 1326 as "the College of the Blessed Virgin Mary":

In spite of my ingrained fears of Rome, and the decision of my reason and conscience against her usages, in spite of my affection for Oxford and Oriel, yet I had a secret longing love of Rome the Mother of English Christianity, and I had a true devotion to the Blessed Virgin, in whose College I lived, whose Altar I served, and whose Immaculate Purity I had in one of my earliest printed Sermons made much of. (p. 165)

Newman was on his "death-bed" as an Anglican when he felt that secret longing and true devotion, and I think we can safely say that when he became a Catholic he was able to demonstrate that love and devotion. In 1849, he published his Discourses to Mixed Congregations and included two sermons on the Blessed Virgin Mary, "The Glories of Mary for the Sake of her Son" and "On the Fitness of the Glories of Mary" in that volume.

Newman was on his "death-bed" as an Anglican when he felt that secret longing and true devotion, and I think we can safely say that when he became a Catholic he was able to demonstrate that love and devotion. In 1849, he published his Discourses to Mixed Congregations and included two sermons on the Blessed Virgin Mary, "The Glories of Mary for the Sake of her Son" and "On the Fitness of the Glories of Mary" in that volume.In the first sermon, we can see that Newman recognizes (having experienced them) the difficulties those outside the Church have with what Catholics believe about the Mother of God and how we practice devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. After speaking about how "great truths of Revelation are all connected together and form a whole", he states:

I am going to apply this remark to the subject of the prerogatives with which the Church invests the Blessed Mother of God. They are startling and difficult to those whose imagination is not accustomed to them, and whose reason has not reflected on them; but the more carefully and religiously they are dwelt on, the more, I am sure, will they be found essential to the Catholic faith, and integral to the worship of Christ. This simply is the point which I shall insist on—disputable indeed by aliens from the Church, but most clear to her children—that the glories of Mary are for the sake of Jesus; and that we praise and bless her as the first of creatures, that we may confess Him as our sole Creator.

So his first thoughts are on the Incarnation of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity:

When the Eternal Word decreed to come on earth, He did not purpose, He did not work, by halves; but He came to be a man like any of us, to take a human soul and body, and to make them His own. He did not come in a mere apparent or accidental form, as Angels appear to men; nor did He merely over-shadow {345} an existing man, as He overshadows His saints, and call Him by the name of God; but He "was made flesh". He attached to Himself a manhood, and became as really and truly man as He was God, so that henceforth He was both God and man, or, in other words, He was One Person in two natures, divine and human. This is a mystery so marvellous, so difficult, that faith alone firmly receives it; the natural man may receive it for a while, may think he receives it, but never really receives it; begins, as soon as he has professed it, secretly to rebel against it, evades it, or revolts from it. This he has done from the first; even in the lifetime of the beloved disciple [St. John] men arose who said that our Lord had no body at all, or a body framed in the heavens, or that He did not suffer, but another suffered in His stead, or that He was but for a time possessed of the human form which was born and which suffered, coming into it at its baptism, and leaving it before its crucifixion, or, again, that He was a mere man. That "in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God, and the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us," was too hard a thing for the unregenerate reason.

Then, after reviewing some of the history of how the Catholic Church developed our understanding of this truth through the early Church Councils, wrestling with how to define the truth of the Incarnation against the various heresies (Arianism, Apollinarism, Nestorianism, etc) that conflicted with what the Church believed, Newman concludes:

You see, then, my brethren, in this particular, the harmonious consistency of the revealed system, and the bearing of one doctrine upon another; Mary is exalted for the sake of Jesus. It was fitting that she, as being a creature, though the first of creatures, should have an office of ministration. She, as others, {349} came into the world to do a work, she had a mission to fulfil; her grace and her glory are not for her own sake, but for her Maker's; and to her is committed the custody of the Incarnation; this is her appointed office,—"A Virgin shall conceive, and bear a Son, and they shall call His Name Emmanuel". As she was once on earth, and was personally the guardian of her Divine Child, as she carried Him in her womb, folded Him in her embrace, and suckled Him at her breast, so now, and to the latest hour of the Church, do her glories and the devotion paid her proclaim and define the right faith concerning Him as God and man. Every church which is dedicated to her, every altar which is raised under her invocation, every image which represents her, every litany in her praise, every Hail Mary for her continual memory, does but remind us that there was One who, though He was all-blessed from all eternity, yet for the sake of sinners, "did not shrink from the Virgin's womb". Thus she is the Turris Davidica, as the Church calls her, "the Tower of David"; the high and strong defence of the King of the true Israel; and hence the Church also addresses her in the Antiphon, as having "alone destroyed all heresies in the whole world".

And in the second sermon in that collection, he continues with the same theme, and with even more tender images of the human relationship between the Mother and her Son:

Now, as you know, it has been held from the first, and defined from an early age, that Mary is the Mother of God. She is not merely the Mother of our Lord's manhood, or of our Lord's body, but she is to be considered {362} the Mother of the Word Himself, the Word incarnate. God, in the person of the Word, the Second Person of the All-glorious Trinity, humbled Himself to become her Son. Non horruisti Virginis uterum, as the Church sings, "Thou didst not disdain the Virgin's womb" [in the Te Deum]. He took the substance of His human flesh from her, and clothed in it He lay within her; and He bore it about with Him after birth, as a sort of badge and witness that He, though God, was hers. He was nursed and tended by her; He was suckled by her; He lay in her arms. As time went on, He ministered to her, and obeyed her. He lived with her for thirty years, in one house, with an uninterrupted intercourse, and with only the saintly Joseph to share it with Him. She was the witness of His growth, of His joys, of His sorrows, of His prayers; she was blest with His smile, with the touch of His hand, with the whisper of His affection, with the expression of His thoughts and His feelings, for that length of time. Now, my brethren, what ought she to be, what is it becoming that she should be, who was so favoured?

These two longer sermons/discourses are most appropriate spiritual reading for the month of August.

In 1864 he answered his old Oxford Movement friend, E.B. Pusey, to defend the recent proclamation of the doctrine of Mary's Immaculate Conception with a public letter, but that's beyond the limits of these brief segments to get into!

In his Meditations and Devotions, he included a series of meditations on the Litany of Loretto for the month of May. He divided these meditations into four parts after two introductions to the month of May: The Immaculate Conception, The Annunciation, Our Lady's Dolours (Sorrows), and The Assumption.

Newman also wrote a Litany to the Immaculate Heart of Mary to be used from August 1 to 15 (the Feast of the Assumption of Our Lady) for private devotion:

Heart of Mary, Pray for us.Heart, after God’s own Heart, Pray for us.

Heart, in union with the Heart of Jesus,

Heart, the vessel of the Holy Ghost,

Heart of Mary, shrine of the Trinity,

Heart of Mary, home of the Word,

Heart of Mary, immaculate in thy creation,

Heart of Mary, flooded with grace, {242}

Heart of Mary, blessed of all hearts,

Heart of Mary, Throne of glory,

Heart of Mary, Abyss of humbleness,

Heart of Mary, Victim of love,

Heart of Mary, nailed to the Cross,

Heart of Mary, comfort of the sad,

Heart of Mary, refuge of the sinner,

Heart of Mary, hope of the dying,

Heart of Mary, seat of mercy,

************************

O most merciful God, who for the salvation of sinners and the refuge of the wretched, hast made the Immaculate Heart of Mary most like in tenderness {243} and pity to the Heart of Jesus, grant that we, who now commemorate her most sweet and loving heart, may by her merits and intercession, ever live in the fellowship of the Hearts of both Mother and Son, through the same Christ our Lord.—Amen.

And for the rest of the month of August, he composed a Litany to the Holy Name of Mary.

Immaculate Heart of Mary, pray for us!Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

Image credit (Public Domain): Maria mit flammendem Herz; Hinterglasbild, 29 x 23 cm; Augsburg oder Murnau, 2. Hälfte 18. Jahrhundert

July 21, 2022

Preview: St. J.H. Newman on St. James the Greater and Predestination

Since Monday, July 25 is the feast of Saint James the Greater, we'll continue our series on the Son Rise Morning Show with an 1835 Parochial and Plain Sermon Newman preached on Saint James' feast day, "Human Responsibility" from volume 2 of those sermons. Either Anna Mitchell or Matt Swaim and I will discuss this sermon at my usual time, about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern.

Since Monday, July 25 is the feast of Saint James the Greater, we'll continue our series on the Son Rise Morning Show with an 1835 Parochial and Plain Sermon Newman preached on Saint James' feast day, "Human Responsibility" from volume 2 of those sermons. Either Anna Mitchell or Matt Swaim and I will discuss this sermon at my usual time, about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern.Please listen live here on EWTN or on your local EWTN affiliate.

Newman takes as his text a verse from the Gospel for this feast: "To sit on My right hand and on My left is not Mine to give; but it shall be given to them for whom it is prepared of My Father." (Matt. 20:23)

As a reminder: The mother of James and John have asked Jesus to grant her sons a special place when He comes into His power: to be seated on either side of Him (she leaves it up to Him which one on which side!). Jesus warns them that there will be a cost for being His followers but then tells them He can't promise that great honor because He is obedient to the Father's Will. That's up to His heavenly Father. (The other Apostles don't like the special attention paid the Sons of Zebedee; who is the more important disciple seems to be a recurring issue for the Twelve [Luke 9:46; Mark 9:33; Matthew 18:1-4]: they even talk about it [Luke 22;24] at the Last Supper!) Jesus reminds them again that they need to have a different view of honor and precedence, which He will model at the Last Supper when He washes their feet [John 13:4-5].

As a reminder: The mother of James and John have asked Jesus to grant her sons a special place when He comes into His power: to be seated on either side of Him (she leaves it up to Him which one on which side!). Jesus warns them that there will be a cost for being His followers but then tells them He can't promise that great honor because He is obedient to the Father's Will. That's up to His heavenly Father. (The other Apostles don't like the special attention paid the Sons of Zebedee; who is the more important disciple seems to be a recurring issue for the Twelve [Luke 9:46; Mark 9:33; Matthew 18:1-4]: they even talk about it [Luke 22;24] at the Last Supper!) Jesus reminds them again that they need to have a different view of honor and precedence, which He will model at the Last Supper when He washes their feet [John 13:4-5].Newman begins:

IN these words, to which the Festival of St. James the Greater especially directs our minds, our Lord solemnly declares that the high places of His Kingdom are not His to give,—which can mean nothing else, than that the assignment of them does not simply and absolutely depend upon Him; for that He will actually dispense them at the last day, and moreover is the meritorious cause of any being given, is plain from Scripture. I say, He avers most solemnly that something besides His own will and choice is necessary, for obtaining the posts of honour about His throne; so that we are naturally led on to ask, where it is that this awful prerogative is lodged. Is it with His Father? He proceeds to speak of His Father; but neither does He assign it to Him, "It shall be given to them for whom it is prepared of My Father." The Father's foreknowledge and design {321} are announced, not His choice. "Whom He did foreknow, them He did predestinate." He prepares the reward, and confers it, but upon whom? No answer is given us, unless it is conveyed in the words which follow,—upon the humble:—"Whosoever will be great among you, let him be your minister; and whosoever will be chief among you, let him be your servant."

Newman is exploring the mystery of Judgment and Eternal Reward, and he is entering the debate of how we humans participate in our own salvation:

Some parallel passages may throw some further light upon the question. In the description our Lord gives us of the Last Judgment, He tells us He shall say to them on His right hand, "Come, ye blessed of My Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world." Here we have the same expression. Who then are the heirs for whom the Kingdom is prepared? He tells us expressly, those who fed the hungry and thirsty, lodged the stranger, clothed the naked, visited the sick, came to the prisoners, for His sake. Consider again an earlier passage in the same chapter. To whom is it that He will say, "Enter thou into the joy of thy Lord?"—to those whom He can praise as "good and faithful servants," who have been "faithful over a few things." (Matthew 25:21, 34-36)

These two passages then carry our search just to the very point which is suggested by the text. They lead us from the thought of God and Christ, and throw us upon human agency and responsibility, for the solution of the question; and they finally lodge us there, unless indeed other texts of Scripture can be produced to lead us on further still. . . . Is this as far as we can go? Does it now depend ultimately on ourselves, or on any one else, that we come to be humble, charitable, diligent, and lovers of God?

Newman then offers a sketch of early Church history on the tension between God's omniscience (knowing who will be saved) and human will and perseverance to obey God's will and commandments, before turning to various Bible verses arguing both sides. For example:

Newman then offers a sketch of early Church history on the tension between God's omniscience (knowing who will be saved) and human will and perseverance to obey God's will and commandments, before turning to various Bible verses arguing both sides. For example:Next, let us inquire whether there be any Scripture reason for breaking the chain of doctrine which the text suggests. Christ gives the Kingdom to those for whom it is prepared of the Father; the Father prepares it for those who love and serve Him. Does Scripture warrant us in reversing this order, and considering that any are chosen to love Him by His irreversible decree? The disputants in question maintain that it does.

1. Scripture is supposed expressly to promise perseverance, when men once savingly partake of grace; as where it is said, "He which hath begun a good work in you, will perform it until the day of Jesus Christ;" [Phil. i. 6.] and hence it is inferred that the salvation of the individual rests ultimately with God, and not with himself. But here I would object in the outset to applying to individuals promises and declarations made to bodies, and of a general nature. The question in debate is, not whether God carries forward bodies of men, such as the Christian Church, to salvation, but whether He has accorded any promise of indefectibility to given individuals? Those who differ from us say, that individuals are absolutely chosen to eternal life; let them then reckon up the passages in Scripture where perseverance is promised to individuals. Till they can satisfy this demand, they have done nothing by producing such a text as that just cited; which, being spoken of the body of Christians, does but impart that same kind of encouragement, as is contained in other general declarations, such as the statement about God's {326} willingness to save, His being in the midst of us, and the like. . . .

In truth, the two doctrines of the sovereign and {327} overruling power of Divine grace, and man's power of resistance, need not at all interfere with each other. They lie in different provinces, and are (as it were) incommensurables. Thus St. Paul evidently accounted them; else he could not have introduced the text in question with the exhortation, "Work out" or accomplish "your own salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God which worketh" or acts "in you." So far was he from thinking man's distinct working inconsistent with God's continual aiding, that he assigns the knowledge of the latter as an encouragement to the former. Let me challenge then a Predestinarian to paraphrase this text. We, on the contrary, find no insuperable difficulty in it, considering it to enjoin upon us a deep awe and reverence, while we engage in those acts and efforts which are to secure our salvation from the belief that God is in us and with us, inspecting and succouring our every thought and deed.

He also offers verses that favor a strict Predestinarian view: that human action and effort mean little when it comes to salvation. But Newman comes back to the view that this is a mystery: that the Church may define some aspects (a la the Council of Trent's decree on Justification?) of it but cannot comprehend it all:

Lastly, there are passages which speak of God's judicial dealings with the heart of man; in which, doubtless, He does act absolutely at His sole will,—yet not in the beginning of His Providence towards us, but at the close. Thus He is said "to Send" on men "strong delusion to believe a lie;" but only on those who "received not the love of the truth that they might be saved." [2 Thess. ii. 10, 11.] Such irresistible influences do but presuppose, instead of superseding, our own accountableness.

These three explanations then being allowed their due weight,—the compatibility of God's sovereignty over the soul, with man's individual agency; the distinction between Regeneration and faith and obedience; and the judicial purpose of certain Divine influences upon the heart,—let us ask what does there remain of Scripture evidence in behalf of the Predestinarian doctrines? Are we not obliged to leave the mystery of human agency and responsibility as we find it? as truly a mystery in itself as that which concerns the Nature and Attributes of the Divine Mind.

Surely it will be our true happiness thus to conduct ourselves; to use our reason, in getting at the true sense of Scripture, not in making a series of deductions from it; in unfolding the doctrines therein contained, not in adding new ones to them; in acquiescing in what is told, not in indulging curiosity about the "secret things" of the Lord our God.

This may be a deep subject to take up on an early Monday morning, but remember that Newman's congregation was in church in the early evening at Sunday's Evensong service, before or after their Tea, listening to him cite chapter and verse! It does seem to me that Newman is setting himself to affirm the Catholic "via media" on this issue, as summarized in the old Catholic Encyclopedia article on Predestination:

Between these two extremes the Catholic dogma of predestination keeps the golden mean, because it regards eternal happiness primarily as the work of God and His grace, but secondarily as the fruit and reward of the meritorious actions of the predestined.

Lord have mercy! Christ have mercy! Lord have mercy!Saint James the Greater, pray for us!Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

Image credit (public domain): Guido Reni - Saint James the GreaterImage credit (public domain): Hans von Kulmbach, Mary Salome and Zebedee with their Sons James the Greater and John the Evangelist, c. 1511

July 14, 2022

Preview: Saint J.H. Newman and Papal Infallibility (July 18, 1870)

On Monday, July 18, we will celebrate the 152nd anniversary of the proclamation of the doctrine of Papal Infallibility at the First Vatican Council in 1870. Therefore, we'll discuss Saint John Henry and Pastor Aeternus during my usual Monday segment on the Son Rise Morning Show. Either Matt Swaim or Anna Mitchell will be my interlocutor. Listen live here on EWTN Radio, at about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern.

On Monday, July 18, we will celebrate the 152nd anniversary of the proclamation of the doctrine of Papal Infallibility at the First Vatican Council in 1870. Therefore, we'll discuss Saint John Henry and Pastor Aeternus during my usual Monday segment on the Son Rise Morning Show. Either Matt Swaim or Anna Mitchell will be my interlocutor. Listen live here on EWTN Radio, at about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern.First, some notes on Newman and the Papacy in general:

On October 6, 1845, just days before he became a Catholic, Blessed John Henry Newman retracted his statements against the Catholic Church and the Papacy. In his Apologia pro Vita Sua, he notes that when he was 15 years old he firmly believed the Pope was the Antichrist. As his religious opinions changed, however, he explains later in the Apologia, how his feelings toward Rome and Papacy changed under the influence of his beloved friend Richard Hurrell Froude, especially regarding some of the medieval popes. Then, while at Littlemore, on his "deathbed as an Anglican" as he put it, and while writing himself into the Catholic Church in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, he noted signs among the Fathers of the Church that argued for Papal Supremacy or Primacy.

Newman met Pope Pius IX while he was studying for the priesthood in Rome in 1846: it was not a promising start to their relationship: when Newman bent down to kiss the Pope’s foot he banged his forehead against the pope's knee. Pope Pius nevertheless, approved Newman's establishment of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in England, gave him an honorary degree of divinity on August 22, 1850, and approved of him being named the Rector of the Catholic University of Ireland in 1851. When Pope Pius IX was planning the First Vatican Council, he asked Newman to come as an advisor to the bishops. Others requested his presence too: Bishop Felix Dupanloup of Orléans, France (who was opposed to a definition of Papal Infallibility) wanted him to be his personal theologian at the Council and Bishop Joseph Brown of Newport, who had delated Newman to Rome over The Rambler incident in 1859, also asked him to be his personal theologian. He declined all three job offers and remained at the Oratory in Birmingham. He was working on the Grammar of Assent at the time.

Newman met Pope Pius IX while he was studying for the priesthood in Rome in 1846: it was not a promising start to their relationship: when Newman bent down to kiss the Pope’s foot he banged his forehead against the pope's knee. Pope Pius nevertheless, approved Newman's establishment of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in England, gave him an honorary degree of divinity on August 22, 1850, and approved of him being named the Rector of the Catholic University of Ireland in 1851. When Pope Pius IX was planning the First Vatican Council, he asked Newman to come as an advisor to the bishops. Others requested his presence too: Bishop Felix Dupanloup of Orléans, France (who was opposed to a definition of Papal Infallibility) wanted him to be his personal theologian at the Council and Bishop Joseph Brown of Newport, who had delated Newman to Rome over The Rambler incident in 1859, also asked him to be his personal theologian. He declined all three job offers and remained at the Oratory in Birmingham. He was working on the Grammar of Assent at the time.In June of 2019 I presented a paper on Newman's reactions to the First Vatican Council and the pending document on Papal Infallibility at Newman University during the Ad Fontes Conference hosted by Eighth Day Institute:

Newman received many letters from concerned converts and other Catholics. His advice was always to remain calm and pray. As he reminded himself and his correspondents, they had become Catholic because they believed “the present Roman Catholic Church is the only Church which is like, and it is very like, the primitive Church.”He recalled the phrase from St. Augustine: securus judicat orbis terrarum! and he relied upon the power of the Holy Spirit to keep the Church from any doctrinal error at a council. As Edward Short points out in Newman and His Contemporaries, he stressed to one of “his converts” when she threatened to leave the Church if Papal Infallibility was defined at the Council, “I say with [Robert] Cardinal Bellarmine whether the Pope be infallible or not in any pronouncement, anyhow he is to be obeyed. No good can come from disobedience . . .” He would make a similar comment in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk. Newman did not think a decree of Papal Infallibility necessary or timely: he was an Inopportunist against the Ultramontanes. . .

When Pastor Aeternus was finally voted on, he was pleased to see that Papal Infallibility was narrowly defined; he waited to see how the dissenting bishops responded: securus judicat orbis terrarum! Newman made no public statement except to again deny rumours that he was going to leave the Catholic Church (he had to make these periodically!)

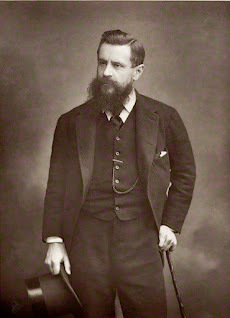

Only when William E. Gladstone, former Prime Minister, published The Vatican Decrees in Their Bearing on Civil Allegiance in 1874 did Newman respond in 1875 with his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, addressing his counter-argument to the pre-eminent Catholic peer, Henry FitzAlan Howard, scion of a family with two martyrs (Philip Howard and William Howard) in its pedigree. Selecting the 15th Duke of Norfolk as his public correspondent was testing Gladstone’s main contention: that Catholics could not be loyal Englishmen if they accepted Papal Infallibility. Was the Earl Marshall of England, who happened to be a Catholic and a graduate of Newman’s Oratory School, not a loyal Englishman? Did Gladstone really mean that?

Only when William E. Gladstone, former Prime Minister, published The Vatican Decrees in Their Bearing on Civil Allegiance in 1874 did Newman respond in 1875 with his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, addressing his counter-argument to the pre-eminent Catholic peer, Henry FitzAlan Howard, scion of a family with two martyrs (Philip Howard and William Howard) in its pedigree. Selecting the 15th Duke of Norfolk as his public correspondent was testing Gladstone’s main contention: that Catholics could not be loyal Englishmen if they accepted Papal Infallibility. Was the Earl Marshall of England, who happened to be a Catholic and a graduate of Newman’s Oratory School, not a loyal Englishman? Did Gladstone really mean that?

Besides, he reminded Gladstone, the Pope’s Infallibility is limited to speaking on matters of faith and morals as abstract doctrine and principles, not on individual decisions of what to do or not to do in a certain situation. . . .

In a later chapter, on “The Vatican Definition” Newman emphasizes that the Pope speaks infallibly only under certain conditions:

He speaks ex cathedrâ, or infallibly, when he speaks, first, as the Universal Teacher; secondly, in the name and with the authority of the Apostles; thirdly, on a point of faith or morals; fourthly, with the purpose of binding every member of the Church to accept and believe his decision.When the Pope is speaking his mind on any subject like the interpretation of scripture, economics, history, etc., he is not infallible because “he is not in the chair of the universal doctor.” Even if the Pope makes dogmatic statements in an encyclical, as Pope John Paul II did in The Gospel of Life, reiterating Catholic teaching against abortion, for example, those are not exercises of Papal Infallibility.

Since the definition of Papal Infallibility in 1870, only one Pope has used this power: Pope Pius XII when defining the doctrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 1950.

In spite of his reservations about the First Vatican Council's conduct, Newman accepted the work of the Council, but he knew that the Church--the whole Church, including the laity and the theologians, needed time to understand the theology and practice of the doctrine of Papal Infallibility. The First Vatican Council was abbreviated by the Franco-Prussian War and the cause of Italian unity, as the Italian Army was soon at the gates; the Papal States were lost and the long period the Pope as "the prisoner of the Vatican" began.

Newman was always ready to obey the Pope and pray for the Pope as this 1866 Sermon preached at the Birmingham Oratory shows. He also helped Catholics and non-Catholics understand Papal Infallibility, providing an explanation that Father John O'Malley, in his book Vatican I: The Council and the Making of the Ultramontane Church , says “soon achieved almost canonical status” by answering Gladstone's objections.

Image Credit: (Public domain): Papa Pio IX fotografato da Adolphe Braun in commemorazione dell'83° compleanno di Sua Santità (I'm not sure which knee Newman bumped!)

Image Credit: (Public domain): Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk (1847-1917)

July 7, 2022

Preview: Saint J.H. Newman on St. Benedict of Nursia

On Monday, July 11, Matt Swaim, or Anna Mitchell (back from maternity leave it was announced before the long July 4/Independence shutdown at the Son Rise Morning Show), and I will talk about what Saint John Henry Newman has to say about Saint Benedict of Nursia. July 11 is Saint Benedict's feast day.

On Monday, July 11, Matt Swaim, or Anna Mitchell (back from maternity leave it was announced before the long July 4/Independence shutdown at the Son Rise Morning Show), and I will talk about what Saint John Henry Newman has to say about Saint Benedict of Nursia. July 11 is Saint Benedict's feast day.As you know by now, I'll be on the Son Rise Morning Show at my usual time: about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern time. Please listen live on EWTN Radio.

While Newman establishing the Catholic University of Ireland, he wrote a series of articles about the history of education from the Academies of Ancient Greece, to Paris, Oxford, and Cambridge, published as the Rise and Progress of Universities. He also wrote two "Benedictine Essays", which were published in the Atlantis of January, 1859. The University of Notre Dame has a single volume edition of these works, edited and introduced by Mary Katherine Tilman.

In the first of the "Benedictine Essays", "The Mission of St. Benedict", Newman examines the founder of Monasticism in the West in the context of education in general:

Education follows the same law: it has its history in Christianity, and its doctors or masters in that history. It has had three periods:—the ancient, the medieval, and the modern; and there are three Religious Orders in those periods respectively, which succeed, one the other, on its public stage, and represent the teaching {366} given by the Catholic Church during the time of their ascendancy. The first period is that long series of centuries, during which society was breaking or had broken up, and then slowly attempted its own re-construction; the second may be called the period of re-construction; and the third dates from the Reformation, when that peculiar movement of mind commenced, the issue of which is still to come. Now, St. Benedict has had the training of the ancient intellect, St. Dominic of the medieval; and St. Ignatius of the modern. And in saying this, I am in no degree disrespectful to the Augustinians, Carmelites, Franciscans, and other great religious families, which might be named, or to the holy Patriarchs who founded them; for I am not reviewing the whole history of Christianity, but selecting a particular aspect of it.Perhaps as much as this will be granted to me without great hesitation. Next, I proceed to contrast these three great masters of Christian teaching with each other. To St. Benedict, then, who may fairly be taken to represent the various families of monks before his time and those which sprang from him (for they are all pretty much of one school), to this great Saint let me assign, for his discriminating badge, the element of Poetry; to St. Dominic, the Scientific element; and to St. Ignatius, the Practical.

These characteristics, which belong respectively to the schools of the three great Teachers, grow out of the circumstances under which they respectively entered upon their work. Benedict, entrusted with his mission almost as a boy, infused into it the romance and simplicity of boyhood. Dominic, a man of forty-five, a graduate in theology, a priest and a Canon, brought with him into religion that maturity and completeness of learning which {367} he had acquired in the schools. Ignatius, a man of the world before his conversion, transmitted as a legacy to his disciples that knowledge of mankind which cannot be learned in cloisters. And thus the three several Orders were (so to say), the births of Poetry, of Science, and Practical Sense.

Poetry and St. Benedict may not be the combination you think of right away! Newman argues that the Benedictine goal was to leave the secular world behind:

Poetry and St. Benedict may not be the combination you think of right away! Newman argues that the Benedictine goal was to leave the secular world behind:The troubled, jaded, weary heart, the stricken, laden conscience, sought a life free from corruption in its daily work, free from distraction in its daily worship; and it sought employments as contrary as possible to the world's employments,—employments, the end of which would be in themselves, in which each day, each hour, would have its own completeness;—no elaborate undertakings, no difficult aims, no anxious ventures, no uncertainties to make the heart beat, or the temples throb, no painful combination of efforts, no extended plan of operations, no multiplicity of details, no deep calculations, no sustained machinations, no suspense, no vicissitudes, no moments of crisis or catastrophe;—nor again any subtle investigations, nor perplexities of proof, nor conflicts of rival intellects, to agitate, harass, depress, stimulate, weary, or intoxicate the soul.

Although he does admit that the monks read, and studied, and developed agricultural and other technological innovations, Newman believes that they were poets because they were not scientists. They did not seek to investigate, analyze, and systematize. Instead, they sought mystery and wonder in their prayer and work. Their poetry

implies that we understand [our surroundings] to be vast, immeasurable, impenetrable, inscrutable, mysterious; so that at best we are only forming conjectures about them, not conclusions, for the phenomena which they present admit of many explanations, and we cannot know the true one. Poetry does not address the reason, but the imagination and affections; it leads to admiration, enthusiasm, devotion, love. The vague, the uncertain, the irregular, the sudden, are among its attributes or sources. Hence it is that a child's mind is so full of poetry, because he knows so little; and an old man of the world so devoid of poetry, because his experience of facts is so wide. . . .

Newman believes St. Benedict and his monks wanted "the sweet soothing presence of earth, sky, and sea, the hospitable cave, the bright running stream" and most of all, quiet, so that one day was "just like another except that it was one step nearer than the day just gone to that great Day, which would swallow up all days, the day of everlasting rest."

Isn't that why we want to go to monasteries on retreat? To be silent, still, and simple?

Newman does not neglect the great work of the monks as chroniclers, transcribers of ancient texts, etc. And he certainaly pays tribute to St. Benedict as the great founder of many monastic orders, as The Rule has been adapted to the Cluniac, Cistercian, Camadolese, and other orders:

St. Benedict, then, like the great Hebrew Patriarch, was the "Father of many nations." He has been styled "the Patriarch of the West," a title which there are many reasons for ascribing to him. Not only was he the first to establish a perpetual Order of Regulars in {371} Western Christendom; not only, as coming first, has he had an ampler course of centuries for the multiplication of his children; but his Rule, as that of St. Basil in the East, is the normal rule of the first age of the Church, and was in time generally received even in communities which in no sense owed their origin to him. Moreover, out of his Order rose, in process of time, various new monastic families, which have established themselves as independent institutions, and are able in their turn to boast of the number of their houses, and the sanctity and historical celebrity of their members. He is the representative of Latin monachism [monasticism] for the long extent of six centuries, while monachism was one; and even when at length varieties arose, and distinct titles were given to them, the change grew out of him;—not the act of strangers who were his rivals, but of his own children, who did but make a new beginning in all devotion and loyalty to him.

But the suggestion that St. Benedict brought "romance and simplicity" and poetry to Western civilization, education, and culture is something to think about for awhile--perhaps on retreat at a monastery.

Saint Benedict of Nursia, pray for us!Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

By the way, Newman intended to write articles on the Dominican contributions to education, but the periodical he was writing for, The Atlantis, disappeared . . .

June 27, 2022

Preview: Newman on Saint Paul (UPDATED Again)

We've rescheduled this interview for Thursday, June 30, at 7:50 am Eastern/6:50 am Central!

UPDATE: Because of the Supreme Court decision on Dobbs, Matt Swaim needs that time slot back on Monday. We'll reschedule later in the week!

Since we celebrate yet another Solemnity next week, that of Saints Peter and Paul, I suggested to Matt Swaim that we take a look at one of Saint John Henry Newman's sermons on Saint Paul during our Monday, June 27 segment on the Son Rise Morning Show. As you know by now, I'll be on the Son Rise Morning Show at my usual time: about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern time. Please listen live on EWTN Radio.

The sermon I've selected is "St. Paul's Characteristic Gift", based upon the verse, "Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me." 2 Cor. xii. 9. Newman preached it in the University Church in Dublin on an auspicious day:

I think it a happy circumstance that, in this Church, placed, as it is, under the patronage of the great names of St. Peter and St. Paul, the special feast days of these two Apostles (for such we may account the 29th of June as regards St. Peter, and today as regards St. Paul) should, in the first year of our assembling here, each have fallen on a Sunday. And now that we have arrived, through God's protecting Providence, at the latter of these two days, the Conversion of St. Paul, I do not like to forego the opportunity, with whatever misgivings as to my ability, of offering to you, my Brethren, at least a few remarks upon the wonderful work of God's creative grace mercifully presented to our inspection in the person of this great Apostle. Most unworthy of him, I know, is the best that I can say; and even that {94} best I cannot duly exhibit in the space of time allowed me on an occasion such as this; but what is said out of devotion to him, and for the divine glory, will, I trust, have its use, defective though it be, and be a plea for his favourable notice of those who say it, and be graciously accepted by his and our Lord and Master.

Newman begins the sermon by contrasting two general types of saints: those who seem (like Saint John the Apostle), "to have no part in earth or in human nature; but to think, speak, and act under views, affections, and motives simply supernatural. If they love others, it is simply because they love God, and because man is the object either of His compassion, or of His praise. If they rejoice, it is in what is unseen; if they feel interest, it is in what is unearthly; if they speak, it is almost with the voice of Angels; if they eat or drink, it is almost of Angels' food alone . . ."

Newman begins the sermon by contrasting two general types of saints: those who seem (like Saint John the Apostle), "to have no part in earth or in human nature; but to think, speak, and act under views, affections, and motives simply supernatural. If they love others, it is simply because they love God, and because man is the object either of His compassion, or of His praise. If they rejoice, it is in what is unseen; if they feel interest, it is in what is unearthly; if they speak, it is almost with the voice of Angels; if they eat or drink, it is almost of Angels' food alone . . ."He classes Saint Paul among the second group: those in "whom the supernatural combines with nature, instead of superseding it,—invigorating it, elevating it, ennobling it; and who are not the less men, because they are saints. They do not put away their natural endowments, but use them to the glory of the Giver; they do not act beside them, but through them; they do not eclipse them by the brightness of divine grace, but only transfigure them. They are versed in human knowledge; they are busy in human society; they understand the human heart; they can throw themselves into the minds of other men; and all this in consequence of natural gifts and secular education."

Then Newman focuses on that verse in which Saint Paul says that he "glories" in his weakness so that the power of Christ dwells in him:

In him, his human nature, his human affections, his human gifts, were possessed and glorified by a new and heavenly life; they remained; he speaks of them in the text, and in his humility he calls them his infirmity. He was not stripped of nature, but clothed with grace and the power of Christ, and therefore he glories in his infirmity. This is the subject on which I wish to enlarge.

A heathen poet has said, Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto. "I am a man; nothing human is without interest to me:" and the sentiment has been widely and deservedly praised. Now this, in a fulness of meaning which a heathen could not understand, is, I conceive, the characteristic of this great Apostle. He is ever speaking, to use his own words, "human things," and "as a man," and "according to man," and "foolishly":—that is, human nature, the common nature of the whole race of Adam, spoke in him, acted in him, with an energetical presence, with a sort of bodily fulness, always under the sovereign command of divine grace, but {96} losing none of its real freedom and power because of its subordination. And the consequence is, that, having the nature of man so strong within him, he is able to enter into human nature, and to sympathize with it, with a gift peculiarly his own.

Newman notes that Saint Paul sympathized on the one hand with the pagans, the Gentiles to whom he especially preached. Even when they wanted to worship him and Barnabas as though they were Hermes and Zeus, Newman says:

he at once places himself on their level and reckons himself among them, and at the same time speaks of God's love of them, heathens though they were. "Ye men," he cries, "why do ye these things? We also are mortals, men like unto you;" and he adds that God in times past, though suffering all nations to walk in their own ways, "nevertheless left not Himself {99} without testimony, doing good from heaven, giving rains and fruitful seasons, filling our hearts with food and gladness." You see, he says, "our hearts," not "your," as if he were one of those Gentiles; and he dwells in a kindly human way over the food, and the gladness which food causes, which the poor heathen were granted. Hence it is that he is the Apostle who especially insists on our all coming from one father, Adam; for he had pleasure in thinking that all men were brethren. "God hath made," he says, "all mankind of one"; "as in Adam all die, so in Christ all shall be made alive."

But in the same, Newman says, Saint Paul had great empathy for Jews, whom he also wanted to bring to Jesus Christ even though he had a special mission to the Gentiles:

"Hath God cast away His people?" he asks; "God forbid. For I also am an Israelite, of the seed of Abraham, of the tribe of Benjamin." "All are not Israelites that are of Israel." And he dwells upon his confident anticipation of their recovery in time to come. "They are enemies," he says, writing to the Romans, "for your sakes;" that is, you have gained by their loss; "but they are most dear for the sake of the fathers; for the gifts and the calling of God are without repentance." "Blindness in part has happened to Israel, until the fulness of the Gentiles should come in; and so all Israel should be saved."

And one more quotation, in which we see a reminder of Newman's great "Heart Speaks to Heart" motto, and his enduring belief that personal influence is an essential way to bringing others to Christ:

To him specially was it given to preach to the world, who knew the world; he subdued the heart, who understood the heart. It was his sympathy that was his means of influence; it was his affectionateness which was his title and instrument of empire. "I became to the Jews a Jew," he says, "that I might gain the Jews; to them that are under the Law, as if I were under the Law, that I might gain them that were under the Law. To those that were without the Law, as if I were without {104} the Law, that I might gain them that were without the Law. To the weak I became weak, that I might gain the weak. I became all things to all men, that I might save all."

Newman regrets that he can't say more about Saint Paul's characteristic gift because his time for preaching is at an end!

Saint Paul the Apostle, pray for us!Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

Image credit (top): Paul and Barnabas at Lystra – painting by Jacob Pynas (MET, 1971.255) This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Shared under a Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Image Credit (St John the Apostle by Rubens): public domain

June 23, 2022

Preview: Newman on Saint Paul (Updated)!

UPDATE: Because of the Supreme Court decision on Dobbs, Matt Swaim needs that time slot back on Monday. We'll reschedule later in the week!

Since we celebrate yet another Solemnity next week, that of Saints Peter and Paul, I suggested to Matt Swaim that we take a look at one of Saint John Henry Newman's sermons on Saint Paul during our Monday, June 27 segment on the Son Rise Morning Show. As you know by now, I'll be on the Son Rise Morning Show at my usual time: about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern time. Please listen live on EWTN Radio.

The sermon I've selected is "St. Paul's Characteristic Gift", based upon the verse, "Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me." 2 Cor. xii. 9. Newman preached it in the University Church in Dublin on an auspicious day:

I think it a happy circumstance that, in this Church, placed, as it is, under the patronage of the great names of St. Peter and St. Paul, the special feast days of these two Apostles (for such we may account the 29th of June as regards St. Peter, and today as regards St. Paul) should, in the first year of our assembling here, each have fallen on a Sunday. And now that we have arrived, through God's protecting Providence, at the latter of these two days, the Conversion of St. Paul, I do not like to forego the opportunity, with whatever misgivings as to my ability, of offering to you, my Brethren, at least a few remarks upon the wonderful work of God's creative grace mercifully presented to our inspection in the person of this great Apostle. Most unworthy of him, I know, is the best that I can say; and even that {94} best I cannot duly exhibit in the space of time allowed me on an occasion such as this; but what is said out of devotion to him, and for the divine glory, will, I trust, have its use, defective though it be, and be a plea for his favourable notice of those who say it, and be graciously accepted by his and our Lord and Master.

Newman begins the sermon by contrasting two general types of saints: those who seem (like Saint John the Apostle), "to have no part in earth or in human nature; but to think, speak, and act under views, affections, and motives simply supernatural. If they love others, it is simply because they love God, and because man is the object either of His compassion, or of His praise. If they rejoice, it is in what is unseen; if they feel interest, it is in what is unearthly; if they speak, it is almost with the voice of Angels; if they eat or drink, it is almost of Angels' food alone . . ."

Newman begins the sermon by contrasting two general types of saints: those who seem (like Saint John the Apostle), "to have no part in earth or in human nature; but to think, speak, and act under views, affections, and motives simply supernatural. If they love others, it is simply because they love God, and because man is the object either of His compassion, or of His praise. If they rejoice, it is in what is unseen; if they feel interest, it is in what is unearthly; if they speak, it is almost with the voice of Angels; if they eat or drink, it is almost of Angels' food alone . . ."He classes Saint Paul among the second group: those in "whom the supernatural combines with nature, instead of superseding it,—invigorating it, elevating it, ennobling it; and who are not the less men, because they are saints. They do not put away their natural endowments, but use them to the glory of the Giver; they do not act beside them, but through them; they do not eclipse them by the brightness of divine grace, but only transfigure them. They are versed in human knowledge; they are busy in human society; they understand the human heart; they can throw themselves into the minds of other men; and all this in consequence of natural gifts and secular education."

Then Newman focuses on that verse in which Saint Paul says that he "glories" in his weakness so that the power of Christ dwells in him:

In him, his human nature, his human affections, his human gifts, were possessed and glorified by a new and heavenly life; they remained; he speaks of them in the text, and in his humility he calls them his infirmity. He was not stripped of nature, but clothed with grace and the power of Christ, and therefore he glories in his infirmity. This is the subject on which I wish to enlarge.

A heathen poet has said, Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto. "I am a man; nothing human is without interest to me:" and the sentiment has been widely and deservedly praised. Now this, in a fulness of meaning which a heathen could not understand, is, I conceive, the characteristic of this great Apostle. He is ever speaking, to use his own words, "human things," and "as a man," and "according to man," and "foolishly":—that is, human nature, the common nature of the whole race of Adam, spoke in him, acted in him, with an energetical presence, with a sort of bodily fulness, always under the sovereign command of divine grace, but {96} losing none of its real freedom and power because of its subordination. And the consequence is, that, having the nature of man so strong within him, he is able to enter into human nature, and to sympathize with it, with a gift peculiarly his own.

Newman notes that Saint Paul sympathized on the one hand with the pagans, the Gentiles to whom he especially preached. Even when they wanted to worship him and Barnabas as though they were Hermes and Zeus, Newman says:

he at once places himself on their level and reckons himself among them, and at the same time speaks of God's love of them, heathens though they were. "Ye men," he cries, "why do ye these things? We also are mortals, men like unto you;" and he adds that God in times past, though suffering all nations to walk in their own ways, "nevertheless left not Himself {99} without testimony, doing good from heaven, giving rains and fruitful seasons, filling our hearts with food and gladness." You see, he says, "our hearts," not "your," as if he were one of those Gentiles; and he dwells in a kindly human way over the food, and the gladness which food causes, which the poor heathen were granted. Hence it is that he is the Apostle who especially insists on our all coming from one father, Adam; for he had pleasure in thinking that all men were brethren. "God hath made," he says, "all mankind of one"; "as in Adam all die, so in Christ all shall be made alive."

But in the same, Newman says, Saint Paul had great empathy for Jews, whom he also wanted to bring to Jesus Christ even though he had a special mission to the Gentiles:

"Hath God cast away His people?" he asks; "God forbid. For I also am an Israelite, of the seed of Abraham, of the tribe of Benjamin." "All are not Israelites that are of Israel." And he dwells upon his confident anticipation of their recovery in time to come. "They are enemies," he says, writing to the Romans, "for your sakes;" that is, you have gained by their loss; "but they are most dear for the sake of the fathers; for the gifts and the calling of God are without repentance." "Blindness in part has happened to Israel, until the fulness of the Gentiles should come in; and so all Israel should be saved."

And one more quotation, in which we see a reminder of Newman's great "Heart Speaks to Heart" motto, and his enduring belief that personal influence is an essential way to bringing others to Christ:

To him specially was it given to preach to the world, who knew the world; he subdued the heart, who understood the heart. It was his sympathy that was his means of influence; it was his affectionateness which was his title and instrument of empire. "I became to the Jews a Jew," he says, "that I might gain the Jews; to them that are under the Law, as if I were under the Law, that I might gain them that were under the Law. To those that were without the Law, as if I were without {104} the Law, that I might gain them that were without the Law. To the weak I became weak, that I might gain the weak. I became all things to all men, that I might save all."

Newman regrets that he can't say more about Saint Paul's characteristic gift because his time for preaching is at an end!

Saint Paul the Apostle, pray for us!Saint John Henry Newman, pray for us!

Image credit (top): Paul and Barnabas at Lystra – painting by Jacob Pynas (MET, 1971.255) This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Shared under a Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Image Credit (St John the Apostle by Rubens): public domain

Preview: Newman on Saint Paul

Since we celebrate yet another Solemnity next week, that of Saints Peter and Paul, I suggested to Matt Swaim that we take a look at one of Saint John Henry Newman's sermons on Saint Paul during our Monday, June 27 segment on the Son Rise Morning Show. As you know by now, I'll be on the Son Rise Morning Show at my usual time: about 6:50 a.m. Central/7:50 a.m. Eastern time. Please listen live on EWTN Radio.

The sermon I've selected is "St. Paul's Characteristic Gift", based upon the verse, "Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me." 2 Cor. xii. 9. Newman preached it in the University Church in Dublin on an auspicious day:

I think it a happy circumstance that, in this Church, placed, as it is, under the patronage of the great names of St. Peter and St. Paul, the special feast days of these two Apostles (for such we may account the 29th of June as regards St. Peter, and today as regards St. Paul) should, in the first year of our assembling here, each have fallen on a Sunday. And now that we have arrived, through God's protecting Providence, at the latter of these two days, the Conversion of St. Paul, I do not like to forego the opportunity, with whatever misgivings as to my ability, of offering to you, my Brethren, at least a few remarks upon the wonderful work of God's creative grace mercifully presented to our inspection in the person of this great Apostle. Most unworthy of him, I know, is the best that I can say; and even that {94} best I cannot duly exhibit in the space of time allowed me on an occasion such as this; but what is said out of devotion to him, and for the divine glory, will, I trust, have its use, defective though it be, and be a plea for his favourable notice of those who say it, and be graciously accepted by his and our Lord and Master.

Newman begins the sermon by contrasting two general types of saints: those who seem (like Saint John the Apostle), "to have no part in earth or in human nature; but to think, speak, and act under views, affections, and motives simply supernatural. If they love others, it is simply because they love God, and because man is the object either of His compassion, or of His praise. If they rejoice, it is in what is unseen; if they feel interest, it is in what is unearthly; if they speak, it is almost with the voice of Angels; if they eat or drink, it is almost of Angels' food alone . . ."

Newman begins the sermon by contrasting two general types of saints: those who seem (like Saint John the Apostle), "to have no part in earth or in human nature; but to think, speak, and act under views, affections, and motives simply supernatural. If they love others, it is simply because they love God, and because man is the object either of His compassion, or of His praise. If they rejoice, it is in what is unseen; if they feel interest, it is in what is unearthly; if they speak, it is almost with the voice of Angels; if they eat or drink, it is almost of Angels' food alone . . ."He classes Saint Paul among the second group: those in "whom the supernatural combines with nature, instead of superseding it,—invigorating it, elevating it, ennobling it; and who are not the less men, because they are saints. They do not put away their natural endowments, but use them to the glory of the Giver; they do not act beside them, but through them; they do not eclipse them by the brightness of divine grace, but only transfigure them. They are versed in human knowledge; they are busy in human society; they understand the human heart; they can throw themselves into the minds of other men; and all this in consequence of natural gifts and secular education."

Then Newman focuses on that verse in which Saint Paul says that he "glories" in his weakness so that the power of Christ dwells in him:

In him, his human nature, his human affections, his human gifts, were possessed and glorified by a new and heavenly life; they remained; he speaks of them in the text, and in his humility he calls them his infirmity. He was not stripped of nature, but clothed with grace and the power of Christ, and therefore he glories in his infirmity. This is the subject on which I wish to enlarge.

A heathen poet has said, Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto. "I am a man; nothing human is without interest to me:" and the sentiment has been widely and deservedly praised. Now this, in a fulness of meaning which a heathen could not understand, is, I conceive, the characteristic of this great Apostle. He is ever speaking, to use his own words, "human things," and "as a man," and "according to man," and "foolishly":—that is, human nature, the common nature of the whole race of Adam, spoke in him, acted in him, with an energetical presence, with a sort of bodily fulness, always under the sovereign command of divine grace, but {96} losing none of its real freedom and power because of its subordination. And the consequence is, that, having the nature of man so strong within him, he is able to enter into human nature, and to sympathize with it, with a gift peculiarly his own.

Newman notes that Saint Paul sympathized on the one hand with the pagans, the Gentiles to whom he especially preached. Even when they wanted to worship him and Barnabas as though they were Hermes and Zeus, Newman says:

he at once places himself on their level and reckons himself among them, and at the same time speaks of God's love of them, heathens though they were. "Ye men," he cries, "why do ye these things? We also are mortals, men like unto you;" and he adds that God in times past, though suffering all nations to walk in their own ways, "nevertheless left not Himself {99} without testimony, doing good from heaven, giving rains and fruitful seasons, filling our hearts with food and gladness." You see, he says, "our hearts," not "your," as if he were one of those Gentiles; and he dwells in a kindly human way over the food, and the gladness which food causes, which the poor heathen were granted. Hence it is that he is the Apostle who especially insists on our all coming from one father, Adam; for he had pleasure in thinking that all men were brethren. "God hath made," he says, "all mankind of one"; "as in Adam all die, so in Christ all shall be made alive."

But in the same, Newman says, Saint Paul had great empathy for Jews, whom he also wanted to bring to Jesus Christ even though he had a special mission to the Gentiles:

"Hath God cast away His people?" he asks; "God forbid. For I also am an Israelite, of the seed of Abraham, of the tribe of Benjamin." "All are not Israelites that are of Israel." And he dwells upon his confident anticipation of their recovery in time to come. "They are enemies," he says, writing to the Romans, "for your sakes;" that is, you have gained by their loss; "but they are most dear for the sake of the fathers; for the gifts and the calling of God are without repentance." "Blindness in part has happened to Israel, until the fulness of the Gentiles should come in; and so all Israel should be saved."