Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 216

November 16, 2014

2015 Eighth Day Institute Symposium

The topic this year is Whatever Happened to Wonder? The Recovery of Mystery in a Secular Age. The speakers include James K.A. Smith, Rod Dreher, Bishop James Conley of Lincoln, Nebraska, James Kushiner, and others.

The schedule is on-line with some titles to be filled in and you can register on-line or by mail. This event, from Thursday, January 15, through Sunday, January 17, includes prayer, a banquet, two receptions at Eighth Day Books, and many opportunities for fellowship and learning. My husband and I plan to go, God willing!

Published on November 16, 2014 23:00

Beyond First Impressions: Gareth Russell's Introduction to the Tudors

My first impressions are that this is a well-illustrated (as befits the title) biographical survey of the Tudor dynasty and its origins. From what I have read so far, Russell acknowledges the fascination of the Tudors and supplies amble evidence of why we are so intrigued by the six monarchs (Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Jane Dudley, Mary I and, Elizabeth I) of this royal family. He has prepared a helpful timeline and list of suggested reading.

Now that I've finished reading An Illustrated Introduction to the Tudors by Gareth Russell, published by Amberley Publishing, here is my full review as promised.

My first impressions quoted above bore out throughout this short book which is part of a series of introductions including the Stuarts and the Georgians among English royal dynasties so far. Amberley might have to break up the Plantagenet dynasty since it keeps these books around 96 pages.

Russell begins with the foundation of the Tudor family through misalliance between Henry V's widow and Owen Tudor and then highlights the major events and issues of each monarch's reign. He pauses to examine certain mysteries or controversies like Anne Boleyn's guilt or innocence of the charges against her and the cause of her fall, why Elizabeth I never married, etc. His reasoning is always careful and decisive: the reader knows what he thinks about these events and people and why.

I did not appreciate the inclusion of Nancy Mitford's comment about Jane Dudley and I think that Russell is wrong to say that Thomas More resigned because he was unhappy about the influence of Reformers at Henry VIII's Court--Thomas More resigned because he realized he had failed to influence Henry VIII on the matter of Papal authority. He had seen the growth of that reforming influence and had stayed at Court until Henry started implementing the break from Rome. As Chancellor, More would have been required to enforce the laws Henry's Parliament had passed--that is why he resigned.

Within the 96 pages I wish there had been room for a conclusion or epilogue. Perhaps even some of the material in the introduction could have been used as a summing up as the dynasty ended with Elizabeth's death in 1603.

Those few issues aside: Russell's prose is clear and colorful and his narrative flows along smoothly, mixed with the interpretation of certain events. The illustrations are excellent and the sidebars provide supplemental information that would otherwise interrupt the narrative--it is a well-designed book. Russell is au courant with the Tudor literature and thus delivers an excellent introduction to the Tudors in this slim volume.

Published on November 16, 2014 22:30

November 15, 2014

The Mendicant Orders and Italian Art in Nashville

Sanctity Pictured: The Art of the Dominican and Franciscan Orders in Renaissance Italy will be on exhibition at The Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tennessee until January 25, 2015:

Beginning in the early thirteenth century, Italy was transformed by two innovative new religious orders known as the Dominicans, founded by Saint Dominic of Caleruega (1170–1221; canonized 1234), and the Franciscans, founded by Saint Francis of Assisi (1181/82–1226; canonized 1228). Whereas earlier religious orders, such as the Benedictines, had cloistered themselves in rural monasteries and lived off income from their property, the Dominicans and Franciscans settled in Italy’s growing cities and lived as mendicants, or beggars, who preached to laymen and women. When Francis and Dominic met in Rome in 1216, they recognized one another as brothers and embraced.

Both orders took a vow of poverty, but soon after the deaths of their founders they were building churches that rivaled cathedrals in size and splendor throughout Italy. With financial assistance from city governments, popes, and the laity, Dominican and Franciscan churches were constructed and filled with altarpieces, crucifixes, fresco cycles, illuminated manuscripts, and liturgical objects. Art became integral to the missions of these orders. Many works are narrative scenes focusing on the Dominican and Franciscan saints whose miracles sanctified contemporary Italian life.

This exhibition is the first to highlight the significant role played by the two major mendicant orders in the great flowering of art in Italy in the period 1200 to 1550. With works drawn from libraries and museums in the United States and the Vatican, it compares and contrasts ways the Dominicans and Franciscans employed art as propaganda and as didactic tools for themselves and their lay followers.

The book accompanying the exhibition is available here.

Published on November 15, 2014 23:00

Another Victim of the English Reformation

The Catholic Herald writes about the eclipse of St. Hugh of Lincoln, brought about by the English Reformation:

The Catholic Herald writes about the eclipse of St. Hugh of Lincoln, brought about by the English Reformation:A leading figure in the 12th century proto-Renaissance, Hugh of Lincoln has suffered a spectacular historical decline, going from being one of the most famous saints in English history at one point to a virtual unknown today.

He was born in Avalon in southern France around 1135. His father was the local lord and a soldier, who later retired to a monastery near Grenoble. Hugh’s mother died when he was sent to boarding school, becoming a religious novice at 15 and a deacon four years later.

In 1159, Hugh was sent to a nearby Benedictine monastery in Saint-Maximin, after which he left the order to enter the Grande Chartreuse, the head monastery of the Carthusian order, just outside Grenoble.

In this famously austere environment he rose to become procurator, before being sent to Witham Charterhouse priory in Somerset, the first of the Carthusian houses in England. . . .

Then, in 1186, he was chosen as Bishop of Lincoln, a role in which he excelled. Generous and kind to his flock, he was also firm in standing up to the Crown. He also helped to improve education in the country and protected the Jews of Lincoln during the persecutions that begun during the Lionheart’s reign.

He also rebuilt Lincoln Cathedral, which had been damaged in 1186, and consecrated St Giles’s in Oxford in 1200. But he was also overworked, taking on the thankless task of being a diplomat for the new king, Richard’s appalling brother, John, and he died on November 16 1200.

Canonised 20 years later, St Hugh was very well known in the later medieval period but became less so after the Reformation.

He is the patron of sick children, shoemakers and swans.

David Farmer's 1985 biography is still probably the most reliable source. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia :

A magnificent golden shrine contained his relics, and Lincoln became the most celebrated centre of pilgrimage in the north of England. It is not known what became of St. Hugh's relics at the Reformation; the shrine and its wealth were a tempting bait to Henry VIII, who confiscated all its gold, silver and precious stones, "with which all the simple people be moch deceaved and broughte into greate supersticion and idolatrye". . . . In the Carthusian Order he is second only to St. Bruno, and the great modern Charterhouse at Parkminster, in Sussex, is dedicated to him.

St. Hugh of Lincoln, pray for us!

Published on November 15, 2014 22:30

November 14, 2014

Chesterton and Newman on English Catholic Literature

Our Wichita chapter of the American Chesterton Society will meet next week at Eighth Day Books to conclude our discussion of The Thing: Why I am a Catholic, reading the last three essays. The first of those three is titled "If They Had Believed" (Chapter 33) and Chesterton brings up John Henry Newman's summing up of English Literature:

Our Wichita chapter of the American Chesterton Society will meet next week at Eighth Day Books to conclude our discussion of The Thing: Why I am a Catholic, reading the last three essays. The first of those three is titled "If They Had Believed" (Chapter 33) and Chesterton brings up John Henry Newman's summing up of English Literature:ONE of the things our enemies do not know is the real case for their own side. It is always for me a great matter of pride that the proudest, the most genuine and the most unanswerable boast, that the Protestants of England could ever make, was made for them by a Catholic. Very few of the Protestants, of his time at any rate, would have had the historical enlargement or enlightenment to make it. For it was said by Newman, when that great master of English was surveying the glorious triumphs of our tongue from Bacon and Milton, to Swift and Burke, and he reminded us firmly that, though we convert England to the true faith a thousand times over, "English literature will always HAVE BEEN Protestant."

That generous piece of candour might well be represented as even too generous; but I think it is very wise for us to be too generous. It is not entirely, or at least not exclusively true. The name of Chaucer is alone enough to show that English literature was English a long time before it was Protestant. Even a Protestant, if he were also English, could ask for nobody more entirely English than Chaucer. He was, in the essential national temper, very much more English than Milton. As a matter of fact, the argument is no stronger for Chaucer than it is for Shakespeare. But in the case of Shakespeare the argument is long and complicated, as conducted by partisans; though sufficiently simple and direct for people with a sense of reality. I believe that recent discoveries, as recorded in a book by a French lady, have very strongly confirmed the theory that Shakespeare died a Catholic. But I need no books and no discoveries to prove to me that he had lived a Catholic, or more probably, like the rest of us, tried unsuccessfully to live a Catholic; that he thought like a Catholic and felt like a Catholic and saw every question as a Catholic sees it. The proofs of this would be matter for a separate essay; if indeed so practical an impression can be proved at all. It is quite self-evident to me that he was a certain real and recognisable Renaissance type of Catholic; like Cervantes; like Ronsard. But if I were asked offhand for a short explanation, I could only say that I know he was a Catholic from the passages which are now used to prove he was an agnostic.

Then Chesterton poses an intriguing question: What "If They Had Believed" in Catholicism?:

But that is another and much more subtle question, which is not the question I proposed to myself in starting this essay. In starting it, I proposed to grant the whole sound and solid truth of Newman's admission; that there has indeed arisen out of the disunion of Europe a great and glorious English Protestant literature; and to make some further speculations upon the point. And I think that nothing could make clearer to the modern English, the one supreme thing that they don't know (which is what our religion really is and why we think it real) than to put this rather interesting historical question. What difference would it have made to the great masters of English literature, if they had been Catholics?

He discusses a few examples, Bunyan, Milton, the Romantics, and then comes back to Milton and even Sir Walter Scott:

I take it that the imaginative magnificence of Milton's epic, in such matters as the War in Heaven, would have been much more convincing, if it had been modelled more on the profound mediaeval mysteries about the nature of angels and archangels, and less on the merely fanciful Greek myths about giants and gods. PARADISE LOST is an immortal poem; but it has just failed to be an immortal religious poem. Those are most happy in reading Milton who can read him as they would read Hesiod. It is doubtful whether those seeking spiritual satisfaction now read him even as naturally as they would read Crashaw. I suppose nobody will dispute that the pageantry of Scott might have taken on a tenfold splendour if he could have understood the emblems of an everlasting faith as sympathetically as he did the emblems of a dead feudalism. For him it was the habit that made the monk; but the habit would have been quite as picturesque if there had been a real monk inside it; let alone a real mind inside the monk, like the mind of St. Dominic or St. Hugh of Lincoln. "English literature will always have been Protestant"; but it might have been Catholic; without ceasing to be English literature, and perhaps succeeding in producing a deeper literature and a happier England.

Coincidentally, Father C. John McCloskey provides more insight into Newman's appreciation of Catholic Literature in The Catholic Thing (get it: Chesterton's The Thing , Father McCloskey in The Catholic Thing --too perfect for coincidence!) and its influences:

Blessed John Henry Newman gave a classic justification for paying attention to such works. In his lectures to the students at the Catholic university that he founded in Dublin in the mid-1800s (later published as The Idea of the University), he discusses the meaning and purpose of Catholic literature. And he draws very interesting distinctions – and lessons from them:

When a “Catholic Literature in the English tongue” is spoken of as a desideratum, no reasonable person will mean by “Catholic works” much more than the “works of Catholics.” The phrase does not mean a religious literature. “Religious Literature” indeed would mean much more than “the Literature of religious men;” it means over and above this, that the subject-matter of the Literature is religious; but by “Catholic Literature” is not to be understood a literature which treats exclusively or primarily of Catholic matters, of Catholic doctrine, controversy, history, persons, or politics; but it includes all subjects of literature whatever, treated as a Catholic would treat them, and as he only can treat them.

Newman was clearly trying to stake out a particular kind of writing that would not be the usual apologetics or spiritual works or theology. In his day, he could assume most people would understand what he was getting at: “Why it is important to have them treated by Catholics hardly need be explained here. . . .For it is evident that, if by a Catholic Literature were meant nothing more or less than a religious literature, its writers would be mainly ecclesiastics; just as writers on Law are mainly lawyers, and writers on Medicine are mainly physicians or surgeons.”

The point has a bearing far beyond what might apply in professional groups or academic disciplines: “if this be so, a Catholic Literature is no object special to a University, unless a University is to be considered identical with a Seminary or a Theological School.”

For Newman, the importance of literature stems from our very nature and God-given powers as human beings, especially language:

if by means of words the secrets of the heart are brought to light, pain of soul is relieved, hidden grief is carried off, sympathy conveyed, counsel imparted, experience recorded, and wisdom perpetuated,—if by great authors the many are drawn up into unity, national character is fixed, a people speaks, the past and the future, the East and the West are brought into communication with each other,—if such men are, in a word, the spokesmen and prophets of the human family,—it will not answer to make light of Literature or to neglect its study; rather we may be sure that, in proportion as we master it in whatever language, and imbibe its spirit, we shall ourselves become in our own measure the ministers of like benefits to others, be they many or few, be they in the obscurer or the more distinguished walks of life,—who are united to us by social ties, and are within the sphere of our personal influence.

Here is the source for Newman's comments on Catholic Literature.

I think I will bring Father McCloskey's article to our meeting next Friday, November 21, at 6:30 p.m., gathering around the table on the second floor of Eighth Day Books--along with the Maple Bacon and Pumpkin Spice cookies I'm going to bake! If you are in Wichita, drop by and join the group! There will certainly be other refreshments and libations!

Published on November 14, 2014 22:30

November 13, 2014

New Blog to Follow: Recusants and Renegades

A facebook friend Martin Robb messaged me with a link to his new blog, Recusants and Renegades:

My name is Martin Robb and I’m a university lecturer, blogger and very amateur historian, based in Hitchin, England.

This blog grew out of my work on family history, and more specifically my interest in my sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Kent and Sussex ancestors, including the Fowle family, who seem to have held on to their Catholic faith, either openly or covertly, through the turbulent events of the Reformation. Now that my research has strayed into exploring a network of families only loosely connected with my own ancestors, I've decided to relocate this part of my research to a separate site. (New readers are encouraged to start here.)

Readers sometimes ask me about ancestry and research--and I really haven't gotten in to that. I probably should and perhaps one day shall. One of my aunts on my mother's side, Aunt Eileen, researched their Threlfall and Smithhisler ancestry so she could become a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The links are on the Threlfall side as I recall going back to colonial Maryland.

My name is Martin Robb and I’m a university lecturer, blogger and very amateur historian, based in Hitchin, England.

This blog grew out of my work on family history, and more specifically my interest in my sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Kent and Sussex ancestors, including the Fowle family, who seem to have held on to their Catholic faith, either openly or covertly, through the turbulent events of the Reformation. Now that my research has strayed into exploring a network of families only loosely connected with my own ancestors, I've decided to relocate this part of my research to a separate site. (New readers are encouraged to start here.)

Readers sometimes ask me about ancestry and research--and I really haven't gotten in to that. I probably should and perhaps one day shall. One of my aunts on my mother's side, Aunt Eileen, researched their Threlfall and Smithhisler ancestry so she could become a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The links are on the Threlfall side as I recall going back to colonial Maryland.

Published on November 13, 2014 22:30

November 12, 2014

New Project: 2015 Cardinal Newman Lecture

I'm preparing for Lent and it isn't even Advent yet?!

I'm preparing for Lent and it isn't even Advent yet?!John McCormick, Director of the Gerber Institute of Catholic Studies at Newman University has asked me to deliver the 2015 Cardinal Newman Week lecture on Ash Wednesday, February 18, 2015, and of course, I've accepted. The title and the description are:

Blessed John Henry Newman on Lent: Affliction and Love

Blessed John Henry Newman was the greatest homilist in nineteenth century England. As an Anglican vicar and as a Catholic priest he prepared his homilies in harmony with the liturgical year, urging his congregations to strive for holiness in every season. In this year's Cardinal Newman Day lecture, local author Stephanie A. Mann will explore Newman's homilies for Lent with their emphasis both on affliction or self-denial and devotion to Jesus in His Passion and Death. Mann will also describe how Newman "practiced what he preached" with examples from his life and personal devotions.

So I'm reading several sermons on Lent from Newman's Parochial and Plain Sermons, outlining my presentation, and gathering other sources. What a great opportunity!

Actually, I've done this before: When I worked as an Admissions Counselor at then Kansas Newman College after graduation from Wichita State University, I delivered the Cardinal Newman Day lecture on Monday, February 21, 1983. My topic: "The Rambler Crisis".

Published on November 12, 2014 22:30

November 10, 2014

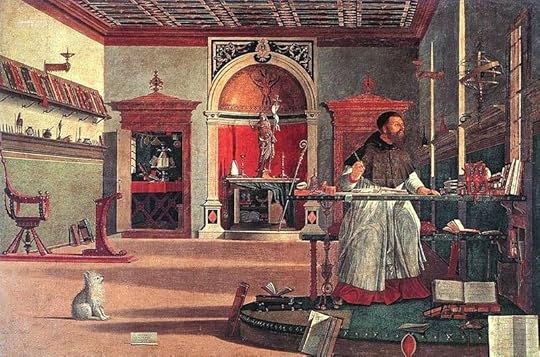

St. Augustine and His Dog in Venice

Willard Spiegelman, the editor-in-chief of the Southwest Review at SMU in Dallas,writes about Vittore Carpacio's Cycle for the Scuola de San Giorgio Degli Schiavoni in Venice for The Wall Street Journal's Masterpiece column. I thoroughly appreciate and agree with his first paragraph:

After a first visit, every tourist to a famous place begins to turn from the hot spots, the three-star must-sees and the crowds—to yearn for intimacy, something out of the way. Nowhere is this quest more natural or essential than in Venice. Forget St. Mark’s Square, the Doge’s Palace and the Rialto. Forget Murano and its glass. Look for the big rewards that come from small packages.

Between the Bellini family, which came before him, and Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese, who followed, the most important Venetian artist was Vittore Carpaccio (1465-1525). He bridged the turn to the new century. His large cycle depicting the legend of St. Ursula is one of the prizes of the Accademia. (These rooms were closed on the days I visited the museum, owing to “weather,” whatever that meant.) But for sheer intensity, variety, elegance and charm, nothing can beat his nine paintings that hang above eye level, beneath a coffered ceiling on the ground floor—they were on the second story until a mid-16th-century rearrangement—of the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, the Dalmatian Confraternity. This lovely spot is both a (long) stone’s throw and a world away from bustling Piazza San Marco.

"After a first visit" assumes that the tourist or traveler goes back to the same city again to see it beyond the tourist's highlights--something about the city or location is so attractive that we want to go back and explore further.

St. Augustine in his study receives a vision of St. Jerome as the latter dies. He stops writing, looks out the window--and his little dog looks up at him, wondering what's outside. As Spiegelman concludes:

We are not in north Africa in the fifth century. We are in Venice, at the turn of the 16th. La Serenissima is the queen of the Adriatic, the point of contact between the riches of the Orient and the western Mediterranean. The Renaissance has begun.

Published on November 10, 2014 22:30

November 9, 2014

For My Review: Gareth Russell's Tudor Overview

Amberley Publishing sent me a review copy of Gareth Russell's new book,

An Illustrated Introduction to THE TUDORS

, part of their "Illustrated Introduction" series. My first impressions are that this is a well-illustrated (as befits the title) biographical survey of the Tudor dynasty and its origins. From what I have read so far, Russell acknowledges the fascination of the Tudors and supplies amble evidence of why we are so intrigued by the six monarchs (Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Jane Dudley, Mary I and, Elizabeth I) of this royal family. He has prepared a helpful timeline and list of suggested reading. Full review forthcoming.On his blog Gareth has announced that he is working on a biography of Henry VIII's fifth wife, Catherine Howard, to be published by Simon & Schuster and HarperCollins: Young and Damned and Fair: The Life and Tragedy of Catherine Howard at the court of King Henry VIII.

Amberley Publishing sent me a review copy of Gareth Russell's new book,

An Illustrated Introduction to THE TUDORS

, part of their "Illustrated Introduction" series. My first impressions are that this is a well-illustrated (as befits the title) biographical survey of the Tudor dynasty and its origins. From what I have read so far, Russell acknowledges the fascination of the Tudors and supplies amble evidence of why we are so intrigued by the six monarchs (Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Jane Dudley, Mary I and, Elizabeth I) of this royal family. He has prepared a helpful timeline and list of suggested reading. Full review forthcoming.On his blog Gareth has announced that he is working on a biography of Henry VIII's fifth wife, Catherine Howard, to be published by Simon & Schuster and HarperCollins: Young and Damned and Fair: The Life and Tragedy of Catherine Howard at the court of King Henry VIII.

Published on November 09, 2014 22:30

November 8, 2014

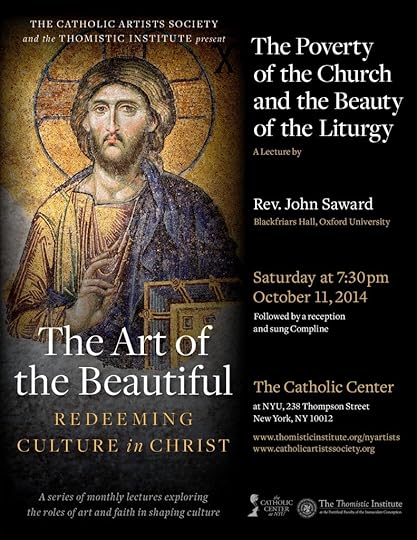

Father John Saward on Beauty and Poverty

You might remember that I mentioned this lecture series several months ago; the first lecture took place in October:

This year’s Art of the Beautiful series opens on Saturday, October 11th at the Catholic Center at NYU. Rev. John Saward (Oxford University) will discuss The Poverty of the Church and the Beauty of the Liturgy.

The lecture will ask: “Is there a place for liturgical beauty in what Pope Francis has called ‘the Church that is poor and for the poor’?”

Now you can hear Father Saward's answer. As Father Saward was previously an Anglo-Catholic, it's appropriate to note that the Ritualist movement in the Church of England after the Oxford Movement was always aligned with great work among the poor, especially in urban areas in the nineteenth century. It is also appropriate to listen to this today while we celebrate the Feast of the Dedication of St. John Lateran in Rome and one could take this virtual tour to see the great beauty of this basilica, the seat of the Pope as the Bishop of Rome.

Published on November 08, 2014 22:30