Sara Paretsky's Blog, page 8

May 12, 2015

The DOLLUS Syndrome

Sara published an essay in the May 1 Booklist on issues around missing voices in contemporary crime fiction

Sara published an essay in the May 1 Booklist on issues around missing voices in contemporary crime fiction

Sara’s new novel Brush Back, about troubled families, Chicago sports, and Illinois politics, will be in bookstores everywhere on July 28

February 24, 2015

Who We Like To Read

After a week of totally unscientific polling, in which visitors to my Facebook page listed their favorite crime/thriller/mystery writers, we came up with a list of 276 beloved writers. They’re listed here in a ranked order–and I’m vain enough to be relieved that visitors to my page like my books! With 276 writers, there are bound to be ones you never encountered, so here’s to some happy reading days ahead–a way to avoid thinking about the endless cold or endless drought–whichever your particular affliction may be.

Happy Readers

Paretsky

Sara

Grafton

Sue

Crombie

Deborah

Penny

Louise

Sayers.

Dorothy

L.

Bland

Eleanor

Taylor

James

P.D.

Allingham

Margery

Christie

Agatha

Kellerman

Faye

Barnes

Linda

Muller

Marcia

Peters

Elizabeth

Stabenow

Dana

Lehane

Dennis

Burke

Alafair

George

Elizabeth

King

Laurie

R.

Rendell

Ruth

Rozan

S.J.

Spencer-Fleming

Julia

Winspear

Jacqueline

Hammett

Dashiell

Stout

Rex

Cody

Liza

Evanovich

Janet

Hess

Joan

Maron

Margaret

McDermid

Val

Millar

Margaret

O’Connell

Carol

Reichs

Kathy

Burke

James

Lee

MacDonald

John

D.

Barr

Nevada

Burke

Jan

Fairstein

Linda

Greenwood

Kerry

Grimes

Martha

Larsson

Åsa

Leon

Donna

Lippman

Laura

Marsh

Ngaio

Rice

Craig

Sjöwall

Maj

Conan

Doyle

Arthur

Kellerman

Jonathan

Krueger

William

Kent

Leonard

Elmore

Vargas

Fred

Atkinson

Kate

Beaton

M.C.

Black

Cara

Davis

Dorothy

Salisbury

Davis

Lindsey

Flynn

Gillian

French

Tana

George

Anne

Gordon

Alison

Gran

Sara

Griffiths

Elly

Gur

Batya

Highsmith

Patricia

Hill

Susan

Hughes

Dorothy

Läckberg

Camilla

MacInnes

Helen

Marklund

Liza

Matera

Lia

McIntosh

D.J.

McPherson

Catriona

Mina

Denise

Moyes

Patricia

Orczy

Emma

Ryan

Hank

Phillipi

Sigurðardóttir

Yrsa

Stewart

Mary

Storey

Alice

Tey

Josephine

Walters

Minette

Waters

Sarah

Chandler

Raymond

Connelly

Michael

Crais

Robert

Creasey

John

Fforde

Jasper

Francis

Dick

Gardner

Earl

Stanley

Grisham

John

Higgins

George

V.

King

Stephen

Larsson

Stieg

MacDonald

Ross

Mankell

Henning

Parker

Robert

Thomas

Ross

Thompson

Jim

Wahlöö

Per

Westlake

Donald

Abbott

Megan

Abbott

Patty

Nase

Adams

Ellery

Aird

Catherine

Albert

Susan

Allen

Stacy

Andrews

Donna

Anthony

Evelyn

Armstrong

Charlotte

Atwood

Taylor

Phoebe

Aubert

Rosemary

Bartlett

Lorraine

Blackwell

Juliet

Blómkvist

Stella

Bowen

Gail

Bowen

Rhys

Brackett

Leigh

Braddon

Mary

Elizabeth

Brand

Christianna

Braun

Lilian

Jackson

Brown

Rita

Mae

Byerrum

Ellen

Campbell

Bonny

Jo

Capponi

Pat

Carlton

Marjorie

Clark

Marcia

Cleeves

Anne

Conley

Jen

Cooper

Susan

Rogers

Cornue

Virginia

Cornwell

Patricia

Coup

Terri

Lynn

Cross

Amanda

Delany

Vicki

Dereske

Jo

DiSilverio

Laura

Donaghue

Emma

DuMaurier

Daphne

Duncan

Elizabeth

J.

Dunn

Carola

Ellison

J.T.

Fossum

Karen

Fradkin

Barbara

Fraser

Antonia

Frazer

Margaret

Freveletti

Jamie

Gagnon

Michelle

Gardner

Lisa

George

Kaye

Gilbert

Michael

Goldstein

Debra

Graham

Caroline

Graves

Sarah

Gray

Alex

Hamilton

Denise

Harlick

Robin

Harris

Charlaine

Harris

C.S.

Hendricks

Vicki

Hillerman

Anne

Jaffarian

Sue

Ann

Jance

J.A.

Jennings

Maureen

Jones

Darynda

Jones

Elizabeth

Keene

Carolyn

Keller

Julia

Kendall

Kay

Kijewski

Karen

La

Plante

Lynda

Linds

Gayle

Locke

Attica

Lockridge

Frances

Lombri

Linda

Lutz

Lisa

MacInerney

Karen

Maffini

Mary

Jane

Maffini

Victoria

Massey

Sujata

Matthews

Francine

McClendon

Lisa

McCullough

Karen

McLeod

Charlotte

Milchman

Jenny

Moss

Jennifer

Munger

Kate

Nabb

Magdalen

Neuhaus

Nele

O’Connor

Gemma

O’Shaughnessy

Perri

Paton

Walsh

Jill

Pawel

Rebecca

Perry

Anne

Pauwels

C.L.

Pickens

Cathy

Robb

J.D.

Roos

Kelly

Rule

Ann

Sanxay

Holding

Elizabeth

Sartor

Nancy

Sellers

L.J.

Shames

Terry

Slaughter

Karin

Sokoloff

Alexandra

Spindler

Erica

Staincliffe

Cath

Stevens

Chevy

Terrell

Beth

Terrell

Jaden

Thompson

Lesley

Tursten

Helene

Unger

Lisa

Welsh

Louise

White

Ethel

Lina

Wilson

Laura

Wilson

Wesley

Valerie

Zeh

Juli

Abbott

Jeff

Atkins

Ace

Baldacci

David

Bronzini

Bill

Bruen

Ken

Buchan

John

Cain

James

M.

Campbell

Robert

Carr

Caleb

Charteris

Leslie

Clifford

Joe

Cohen

Gabriel

Cohen

Jeff

Costain

Thomas

B.

Crispin

Edmund

Dexter

Colin

Dickson

Carr

John

Freeling

Nicholas

Gil

Bartholomew

Goldsborough

Robert

Grabenstein

Chris

Greeley

Andrew

Greene

Graham

Hallinan

Tim

Handler

David

Harris

Thomas

Hewson

David

Hiaasen

Carl

Hillerman

Tony

Hopkins

Bill

Hughes

Declan

Innes

Michael

Isles

Greg

James

Dean

James

Seeley

Kerr

Phillip

Koryta

Michael

Lockridge

Richard

McGarrity

Michael

McGinty

Adrian

Monson

Mike

Nesbø

Jo

Neville

Stuart

Patterson

James

Pears

Iain

Peters

Ellis

Pierce

Rob

Pitts

Tom

Poe

Edgar

Allen

Preston

Douglas

Queen

Ellery

Rankin

Ian

Rhatigan

Chris

Rosenfelt

David

Sansom

C.J.

Simenon

Georges

Twain

Mark

White

Dave

Willieford

Charles

January 3, 2015

Miss Bianca: A Cold WAr Story

Miss Bianca

by Sara Paretsky

Abigail made her tour of the cages, adding water to all the drinking bowls. The food was more complicated, because not all the mice got the same meal. She was ten years old and this was her first job; she took her responsibilities seriously. She read the labels on the cages and carefully measured out feed from the different bags. All the animals had numbers written in black ink on their backs; she checked these against the list Bob Pharris had given her with the feeding instructions.

“That’s like being a slave,” Abigail said, when Bob showed her how to match the numbers on the mice to the food directives. “It’s not fair to call them by numbers instead of by name, and it’s mean to write on their beautiful fur.”

Bob just laughed. “It’s the only way we can tell them apart, Abby.”

Abigail hated the name Abby. “That’s because you’re not looking at their faces. They’re all different. I’m going to start calling you Number Three because you’re Dr. Kiel’s third student. How would you like that?”

“Number Nineteen,” Bob corrected her. “I’m his nineteenth student, but the other sixteen have all gotten their PhD’s and moved on to glory. Don’t give the mice names, Abby: you’ll get too attached to them and they don’t live very long.”

In fact, the next week, when Abigail began feeding the animals on her own, some of the mice had disappeared. Others had been moved into the contamination room, where she wasn’t supposed to go. The mice in there had bad diseases that might kill her if she touched them. Only the graduate students or the professors went in there, wearing gloves and masks.

Abigail began naming some of the mice under her breath. Her favorite, number 139, she called “Miss Bianca,” after the white mouse in the book The Rescuers. Miss Bianca always sat next to the cage door when Abigail appeared, grooming her exquisite whiskers with her little pink paws. She would cock her head and stare at Abigail with bright black eyes.

In the book, Miss Bianca ran a prisoner’s rescue group, so Abigail felt it was only fair that she should rescue Miss Bianca in turn, or at least let her have some time outside the cage. This afternoon, she looked around to make sure no one was watching, then scooped Miss Bianca out of her cage and into the pocket of her dress.

“You can listen to me practice, Miss Bianca,” Abigail told her. She moved into the alcove behind the cages where the big sinks were.

Dr. Kiel thought Abigail’s violin added class to the lab, at least that’s what he said to Abigail’s mother, but Abigail’s mother said it was hard enough to be a single mom without getting fired in the bargain, so Abigail should practice where she wouldn’t disturb the classes in the lecture rooms or annoy the other professors.

Abigail had to come to the lab straight from school. She did her homework on a side table near her mother’s desk, and then she fed the animals and practiced her violin in the alcove.

“Today Miss Abigail Sherwood will play Bach for you,” she announced grandly to Miss Bianca.

She tuned the violin as best she could and began a simplified version of the first sonata for violin. Miss Bianca stuck her head out of the pocket and looked inquiringly at the violin. Abigail wondered what the mouse would do if she put her inside. Miss Bianca could probably squeeze in through the F hole, but getting her out would be difficult. The thought of Mother’s rage, not to mention Dr. Kiel or even Bob Pharris’s, made her decide against it.

She picked up her bow again, but heard voices out by the cages. When she peered out, she saw Bob talking to a stranger, a small woman with dark hair.

Bob smiled at her. “This is Abby; her mother is Dr. Kiel’s secretary. Abby helps us by feeding the animals.”

“It’s Abigail,” Abigail said primly.

“And one of the mouses, Abigail, she is living in your—your—” the woman pointed at Miss Bianca.

“Abby, put the mouse back in the cage,” Bob said. “If you play with them, we can’t let you feed them.”

Abigail scowled at the woman and at Bob, but she put Miss Bianca back in her cage. “I’m sorry, Miss Bianca. Mamelouk is watching me.”

“Mamelouk?” the woman said. “I am thinking your name ‘Bob?’”

Mamelouk the Iron-Tummed was the evil cat who worked for the jailor in The Rescuers, but Abigail didn’t say that, just stared stonily at the woman, who was too stupid to know that the plural of “mouse” was mice, not “mouses.”

“This is Elena,” Bob told Abigail. “She’s Dr. Kiel’s new dishwasher. You can give her a hand, when you’re not practicing your violin or learning geometry.”

“Is allowed for children working in the lab?” Elena asked. “In my country, government is not allowing children work.”

Abigail’s scowl deepened: Bob had been looking at her homework while she was down here with the mice. “We have slavery in America,” she announced. “The mice are slaves, too.”

“Abigail, I thought you liked feeding the animals.” Dr. Kiel had come into the animal room without the three of them noticing.

He wore crepe-soled shoes which let him move soundlessly through the lab. A short stocky man with brown eyes, he could look at you with a warmth that made you want to tell him your secrets, but just when you thought you could trust him, he would become furious over nothing that Abigail could figure out. She had heard him yelling at Bob Pharris in a way that frightened her. Besides, Dr. Kiel was her mother’s boss, which meant she must never EVER be saucy to him.

“I’m sorry, Dr. Kiel,” she said, her face red. “I only was telling Bob I don’t like the mice being branded, they’re all different, you can tell them apart by looking.”

“You can tell them apart because you like them and know them,” Dr. Kiel said. “The rest of us aren’t as perceptive as you are.”

“Dolan,” he added to a man passing in the hall. “Come and meet my new dishwasher—Elena Mirova.”

Dr. Dolan and Dr. Kiel didn’t like each other. Dr. Kiel was always loud and hearty when he talked to Dr. Dolan, trying too hard not to show his dislike. Dr. Dolan snooped around the lab looking for mistakes that Dr. Kiel’s students made. He’d report them with a phony jokiness, as if he thought leaving pipettes unwashed in the sink was funny when really it made him angry.

Dr. Dolan had a face like a giant baby’s, the nose little and squashed upward, his cheeks round and rosy; when Bob Pharris had taken two beakers out of Dr. Dolan’s lab, he’d come into Dr. Kiel’s lab, saying, “Sorry to hear you broke both your arms, Pharris, and couldn’t wash your own equipment.”

He came into the animal room now and smiled in a way that made his eyes close into slits. Just like a cat’s. He said hello to Elena, but added to Dr. Kiel, “I thought your new girl was starting last week, Nate.”

“She arrived a week ago, but she was under the weather; you would never have let me forget it if she’d contaminated your ham sandwiches—I mean your petri dishes.”

Dr. Dolan scowled, but said to Elena, “The rumors have been flying around the building all day. Is it true you’re from eastern Europe?”

Dolan’s voice was soft, forcing everyone to lean toward him if they wanted to hear him. Abigail had trouble understanding him, and she saw Elena did, too, but Abigail knew it would be a mistake to try to ask Dr. Dolan to speak more slowly or more loudly.

Elena’s face was sad. “Is true. I am refugee, from Czechoslovakia.”

“How’d you get here?” Dolan asked.

“Just like your ancestors did, Pat,” Dr. Kiel said. “Yours came steerage in a ship. Elena flew steerage in a plane. We lift the lamp beside the golden door for Czechs just as we did for the Irish.”

“And for the Russians?” Dolan said. “Isn’t that where your people are from, Nate?”

“The Russians would like to think so,” Kiel said. “It was Poland when my father left.”

“But you speak the lingo, don’t you?” Dolan persisted.

There was a brief silence. Abigail could see the vein in Dr. Kiel’s right temple pulsing. Dolan saw it also and gave a satisfied smirk.

He turned back to Elena. “How did you end up in Kansas? It’s a long way from Prague to here.”

“I am meeting Dr. Kiel in Bratislava,” Elena said.

“I was there in ’66, you know,” Dr. Kiel said. “Elena’s husband edited the Czech Journal of Virology and Bacteriology and the Soviets didn’t like their editorial policies—the journal decided they would only take articles written in English, French or Czech, not in Russian.”

Bob laughed. “Audacious. That took some guts.”

Abigail was memorizing words under her breath to ask her mother over dinner: perceptive, editorial policies, audacious.

“Perhaps not so good idea. When Russian tanks coming last year, they putting husband in prison,” Elena said.

“Well, welcome aboard,” Dr. Dolan said, holding out his soft white hand to Elena.

She’d been holding her hands close to her side, but when she shook hands Abigail saw a huge bruise on the inside of her arm, green, purple, yellow, spreading in a large oval up and down from the elbow.

”They beat you before you left?” Dr. Dolan asked.

Elena’s eyes opened wide; Abigail thought she was scared. “Is me, only,” she said, “me being—not know in English.”

“What’s on today’s program?” Dr. Kiel asked Abigail abruptly, pointing at her violin.

“Bach.”

“You need to drop that old stuffed shirt. Beethoven. I keep telling you, start playing those Beethoven sonatas, they’ll bring you to life.” He ruffled her hair. “I think I saw your mother putting the cover over her typewriter when I came down.”

That meant Abigail was supposed to leave. She looked at Miss Bianca, who was hiding in the shavings at the back of her cage. It’s good you’re afraid, Abigail told her silently. Don’t let them catch you, they’ll hurt you or make you sick with a bad disease.

November 18, 2014

Voices on the Margins

Remarks to open the session on “Voices on the Margins,” Bouchercon 2014, Long Beach

We live in a society that is contemptuous of the written word. Many, perhaps most, cities and states in America have cut budgets for schools and libraries repeatedly in the last several years. We easily find money for sports arenas, we subsidize members of Congress who own cotton farms, but we make no pretense of putting money into supporting the written word. In that sense, every person at this convention, readers and writers, live on the margin of American society.

Eddie embraces Clare O’Donoghue, Jamie Freveletti, Charlaine Harris, and me at the Voices event

As lovers of crime fiction, we are further marginalized by writing genre fiction. We aren’t writers, we are crime writers. Every now and then a carrot bobs up in the stew and is proclaimed as having “transcended the genre.” Kate Atkinson, for instance, regularly “transcends the genre.” The rest of us are hacks.

Every word used to pinpoint our identity pushes further to the edge of the page, away from the center: I am a woman, white, heterosexual, WEEJ, progressive, feminist, grandmother crime writer. Never simply a writer. All those labels make up part of my identity, and my identity informs my writing, but I try to transcend my identity, to write about people from many backgrounds, many viewpoints. I try to be faithful to my voice, to my gift, to that incredible magic, the word made visible.

Every person at this convention takes part in many identities. We have Tea Party activists, socialists, anarchists, feminists, Lesbians, Gay, Trans-gendered, African-American, Jewish, Muslim, Atheist, Christian, Asian-American men, women who like serial killers or cozies or true crime or espionage or PI’s or or or…

The one thing we share is that we are passionate about the written word, whether we are writers, readers, librarians, editors, agents. We cannot let ourselves be splintered by identity politics. We must find ways of coming together around our shared passion in a world that devalues literacy and the literate.

(by the way, a WEEJ is a white Eastern-European Jew)

October 28, 2014

Sara reviews for the New York Times

October 15, 2014

Climate Change Ballad Number 1

The story of 35000 walruses crowded together on an Alaska beach because of the disappearance of Arctic ice distressed me as I’m sure it did you. I don’t know if my Climate Change Ballad really helps the situation, but it was the only response I could come up with in the moment.

In the western U.S.

On the Puget Coast Sound

The walruses play

Where the oysters abound

They dive to the bottom

Then swim on their backs

Where they float into shore

To eat their small snacks

Of oysters, and mussels

Or plankton and snails

Which their friend, Captain Tony,

Sets out in large pails.

For Tony loves oysters

And mussels and such

He eats what he catches

And doesn’t take much.

In April one year,

Maybe two-oh twenty-four

The walrus Queen, Olga,

Swam up to the shore.

She slapped on the sand

And gave a great shout.

“Tony! Why are there no

Tasty oysters about?”

Walruses crowded together on beach

“I know,” Tony wept.

“I know all too well.

The acidic ocean

Destroyed all their shells.”

“The ocean’s acidic?”

Olga wept bitter tears.

“How did this happen?

How soon will it clear?”

“Carbon,” Tony sighed.

“We burned too much fuel

In coal and in wood

But above all in oil.

“Carbon in air

Falls down to the ground

It pours down in rain

Right into the Sound.”

“A continent floats

Out in the south seas

The size of two Texas’

And full of disease.

“It’s where bottles and diapers

And plastic decay

Into one giant island

That grows every day.

“This island, Plastarctica,

Almost all life rejects:

No birds, no more fishes

Just lots of insects

“Are all that can live

In the tar and the waste

Those birds that land there

Die in pain and in haste.

Plastarctica

“Oh, no,” Olga wailed

And gave a loud cry.

“No fishes, no oysters,

My babies will die.

“You must clean the ocean

There’s much work to do

Get rid of that carbon

We’re all counting on you.”

So Tony got cracking.

He called all his friends.

They studied the oceans;

They published the trends.

They wrote to the Congress

Explaining the science:

“We’re killing the planet

Due to carbon reliance!

“We see every day

It’s getting much hotter

Himalayan ice

Is turning to water.”

“Ridiculous man,”

Was the answer he got.

“There’s no climate change;

That’s all tommy-rot!”

The priests shouted loudly

“You all are effete!

You’re part of the atheist

Leftist elite!”

Captain Tony tried harder.

“You can still drive your Lexus.

Just pay more for gas

And pay higher taxes.

“Don’t subsidize oil

Use solar and wind.

Ride buses and trains.

Go by bike when you can.”

“Higher taxes, you mad man!”

The CEO’s shouted.

“We need bigger profits!

It’s what we’re entitled.”

“Pay more for bottles?”

The public all screamed.

“Buy cheap and discard—

It’s America’s dream.”

Next year Himalayan

Ice came barreling down.

A billion Chinese

And Indians drowned.

The Florida waters

Rose up ten feet high.

The people fled inland

So they could stay dry.

There was less food to eat,

Less water to drink.

No place to stay cool,

Birds and trees grew extinct.

“God’s punishing us

For believing in science.

Only the Bible

Is there for reliance,”

The ministers said

From every old creed.

“Turn to prayer, turn to Scripture,

But don’t give up greed.”

Meanwhile the armies

Gathered for battle.

With less food to eat

Their sabres all rattled.

Who knows which country

First dropped the big bomb,

But soon they all followed

And a great giga-ton

Of nuclear ash

Fell to the ground.

People burned, children died

And in Puget Sound

Queen Olga floated

Not to play; she was dead.

Her body grew bloated;

On her children she bled.

Captain Tony sat quietly

Out by the ocean.

His friends gathered round him

To find a solution

To nuclear winter.

There was little to do,

But wait ‘til it lifted

Say in Thirty-oh Two.

But in Texas and Egypt

In Chile and Britain

In their various pulpits

The clerics all threatened:

“Who caused this disaster

If not folk in science?

This shows that they

Treated our God with defiance!”

The people responded

As if in one voice,

“Kill Captain Tony!

He’s left us no choice!”

They created big fires

Out of wood chips and oil

And soon Captain Tony

Was brought to the boil.

Cap’n Tony burned at the stake

“Now that he’s gone

With his atheist elite

God will reward us

With more food to eat!”

But the Divine Justice

Gave no quick answer

To famine, pollution

And fast-growing cancer.

For thousands of years

The planet seemed dead

Humans fought rats and roaches

Over rare bits of food.

Now and again

In the midst of the sludge

A poet would reach out

To learn ancient knowledge

But the Kochs and their ilk

Were still hoarding wealth

They bought off the rulers

They did it by stealth

And roused up the rabble

Whatever the creed

To hunt and stone poets

And cheer while they bled.

Slowly but surely

Radiation decayed

Birds re-emerged

A few walruses played

Out in the waters

Near old Puget Sound

Where occasionally now

A new oyster was found.

And more slowly still,

Despite threats of violence

Brave women and men

Re-committed to science.

Captain Tony’s nth grandchild

A bright kid called LuAnn

Studied protons and neutrons,

And even the muon.

While off on the tundra

Her cousin Guilffoyle

Was shooting the wolves

While drilling for oil.

September 8, 2014

Words in Honor of Dorothy Salisbury Davis (1916-2014)

I went to Dorothy’s home town in Sneden’s Landing for her interment and memorial. Although she had a long and rich life, it’s still very hard to know that this is the end. Among the people who spoke were Peggy Friedman, publisher of New Directions, two neighbors, and a man from a program in Harlem for which Dorothy had organized great support.

With Dorothy in 1994

Some people wanted a copy of my remarks, so I include them here:

This is the first time I’ve come to this town and to this church without Dorothy, and it is hard.

I first met Dorothy Salisbury Davis in 1986, when we both were taking part in the first national conference on women in the crime fiction world. Earnest young feminist that I was, I talked about how women smile as a sign of subservience: see me grin, you don’t have to take me seriously.

Dorothy responded with a wry tweak at me, but then gave me her own incandescent smile. I fell in love and never fell out of it. Over the years, she often remembered that first meeting, that smile. She told me that when her parents came to the orphanage where she’d been placed, looking for a boy who might grow up to help on the farm, her mother looked down at Dorothy’s cot. Dorothy smiled up at her and both parents forgot about wanting a boy, although Dorothy grew up doing her share of farmwork.

Once when she’d made lobsters for dinner, I watched in awe as she carried the pot of hot water, weighing about 40 pounds, to the back door to toss it into the yard. She said, “You never lose the muscles you get from milking cows as a child.

Dorothy said her first writing came when she was about four, standing on tiptoe to write as high up on the wall over her head as she could. Her mother, who had a fierce passion for her daughter, might not have relished the wall scribbles, but she did everything else in her power to move Dorothy from life as a housemaid or tenant farmer into the world of writing and the arts.

Dorothy’s mother died while she was still at college, but her influence on Dorothy’s life was deep and abiding. Her mother was an Irish immigrant; her brogue can be heard in at least one character’s voice in almost every book. More than that, her mordant tongue—“You can get used to anything, even hanging, if you hang long enough—“ lives on in the biting words of many of Dorothy’s characters, likeDetective Bassett In Black Sheep, White Lamb, who says of a woman that “she pecked over her obsessions like a crow at a corpse.”

Our friendship deepened during long walks along the Hudson and in late night conversations over whisky—until a few years ago Dorothy could easily outdrink me so I never tried catching up. We’d stay up until one or two and vow the next morning that we wouldn’t do that again—not until the next time.

We didn’t agree on everything—for reasons I never understood, this wise, insightful woman was a Mets fan. Still, I loved her enough to give her a Mets warm-up jacket for her 80th birthday.

I could write a book on what I learned from Dorothy about life in this world, the comic and the tragic and the valuable daily in-between. She introduced me to Flannery O’Conner, a writer she prized over most others. O’Connor said “Fiction is about everything human, and we are made out of dust: if you scorn getting yourself dusty, you shouldn’t try to write fiction. It’s not a grand enough job for you.”

Dorothy was like O’Connor, with a tragi-comic sense of life as well as an awareness that villains and heroes are neither wholly one nor the other. Like O’Connor, Dorothy was willing to roll up her sleeves and get her hands dusty in the business of exploring and writing about human frailty and strength.

Dorothy often said that she identified more with her villains than her heroes, because she understood their motivations better. As I reread her novels, I think what she meant is that she understood what lies behind villainy.

Her novel Where the Dark Streets Go tells the story of a priest who is summoned to the side of a man dying from a knife wound. Most crime writers would have pursued the murder inquiry, but Dorothy treated that as a backdrop to the struggle by the priest to understand himself, his passions, his calling. Through Father Joseph, Dorothy laid bare her own struggles in a naked and highly courageous way—getting herself dusty with a vengeance.

Dorothy sometimes played a writing game with me that I think of as, “Whose Voice Are You?” If we were at a restaurant, for instance, observing a waiter deal with a demanding patron, she’d say, if you were writing that story, who would you be? She herself chose the waiter, vibrating between an angry diner and a furious chef.

“Whose Voice Are You” helped deepen my sense of empathy for the people around me and by extension for the characters I create in my own fiction. Dorothy saw—widely and deeply—but she didn’t judge. That’s a lesson I still haven’t mastered.

The last time I saw Dorothy, near her 98th birthday, she told me she’d decided what saint she wanted to greet her when she died. I expected her to say Francis of Assisi, since she had a special devotion for him.

“Teresa of Avila,” she told me. “If God could welcome someone of her rebellious and questioning spirit, I know he can welcome me.”

Teresa, your patron child has come home. I hope you were there to greet her and lead her across the river.

If I were going to write that story, I would do it in Teresa’s voice. I would have her see that incandescent smile, and fall in love forever.

August 28, 2014

Home is the sailor

And I’m home, as well. Time goes too quickly these days, so I want to write a little about my recent trip to the UK (soon to be only a K?) before I forget everything. I traveled with my husband, who hasn’t felt like making a trip for a number of years now, and we spent our first week in Edinborough, partly to stay with very beloved friends, and partly so I could take part in the Edinborough Book Festival. I was on a panel with Tom Rob Smith, a young but very deep-thinking writer, best known for his book Child 44, (soon to be a major motion picture.) The ever-witty journalist Jackie McGlone moderated.

Photo taken by the Guardian Newspaper’s Murdo MacLeod at the Book Fair

I love Edinborough and I love the Fringe. I walked in the Botanics, and while my husband played pool most afternoons, friends and I went to plays, concerts, one-woman shows, a Georgian production of Animal Farm. and a very strong production of David Mamet’s Race by a South African troupe.

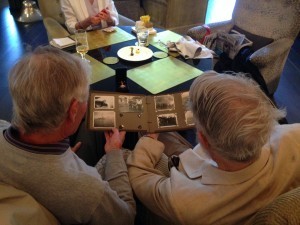

Before coming home, we spent four days in London. Courtenay had a chance to meet with the son of one of the men who served with him on the Apollo during the Normandy Invasion. For some reason, the Royal Navy let Mr. Jackson take photos on board both the warship where he did most of his duty and during the Murmansk run, when Allied ships underwent great risks from both weather and German assault to keep the blockaded Russians in food and materiel. I have a picture of Courtenay and Peter Jackson going through some of those photos in the lobby of our hotel.

Courtenay Wright and Peter Jackson looking at Peter’s father’s WW II photos

Sara, Courtenay, Pippa and Peter Jackson talking over WW II

I also got to catch up with old friends in London whom I don’t often see. Liza Cody and I went to the National Portrait Gallery where there’s a special exhibit on about Virginia Woolf. I’m always intrigued by her, envious of the intellectual life she and her sister shared with their extraordinary circle of writers and artists, and troubled by her illness and death. No easy answers there.

I had breakfast with the fourteen-year-old daughter of another beloved friend. Like her mother, this young woman is a gifted reader, and treated me to formidable insights on fiction, television and film. Can’t wait to see what her journey will be like in adulthood.

Treating myself to these beautiful earrings at the Scottish Gallery in Edinborough

Wearing a WW I helmet at the Imperial War Museum

Finding the perfect cappuccino at Coffee Angel in Edinborough

A harpsichord that Mozart played on, used in a live concert by John Kitchen in Edinborough

Enjoying the sunshine in Hyde Park, London

We flew home on the 26th–8 1/2 hours to cover the 3000 miles from London to O’Hare, 1 1/2 hours to cover the 27 miles from O’Hare to our house. Today I walked to Lake Michigan, feel happy, lucky to live in such a beautiful city but am extraordinarily glad I got to be in Edinborough and London. It was Robert Louis Stevenson, an Edinborough writer, who wrote “Home is the sailor.” (Under the wide and starry sky/Dig a grave and let me lie//Gladly I lived, and gladly died/And I laid me down with a will. /This be the verse you ‘grave for me:/Here he lies where he longed to be/Home is the sailor, home from the sea/And the hunter, home from the hill.)

July 4, 2014

Happy 4th

When I was a child, before my family imploded, my father used to take us for a walk on the 4th and retell the story of the �Revolution. We would shiver with the soldiers in Valley Forge, and celebrate the crossing of the Delaware. At home we would read the Declaration of Independence, make ice cream in a hand-cranked freezer that my mother’s grandmother had used when her husband returned to Illinois from his service in the Civil War. We’d finish the evening with fireworks in our small-town back yard.

Ice cream churn

We knew another part of the story, too. My father’s mother crossed the Atlantic alone at fourteen, around 1908. Her father, my great-grandfather, had been murdered in a pogrom near Vilna–a mob broke into the house and shot him in front of his wife and children. The mob then paraded through Vilna singing “Te Deum,” thanking God for the death of another Jew. My granny, the oldest of eight children, was at risk; her mother shipped her to the New World. As she sailed into New York Harbor, under the outstretched arm of the lady with the lamp, she was lonely, scared, but safe. Never again would her life be in danger because of her religion.

My granny never saw her mother or most of her siblings again. Two sisters joined her in New York in 1920, but by 1936, our borders were closed. Jews and others whom Hitler persecuted before war began had no place to turn. We even sent back a shipload of children, Jewish refugees from Europe, before the war began outright. My great-grandmother, her other five children, and their children, were murdered in the forests outside Vilna in 1942, down to the smallest baby in arms.

On this Fourth of July, as on many, my heart is pulled in many directions. I have a wistful nostalgia for our small-town Fourth, the parade, the walk and history with my dad, the ice cream, the friends who came over to enjoy it with us. I grieve for all those turned away from our borders.

As women make the perilous journey to this country, traveling up from Guatemala through Mexico to our hostile borders, their danger of rape is so high that the jefes who extort money to shepherd people through the deserts force women to take contraceptives so that their rapes don’t end in pregnancies. We make the wall high, we scream hysterically, we demonize, but even today, as our roads crumble and our schools fail, people still want to come. They can help us be a better country, but we are like the old lady and the onion in Russian folklore:

onion roots

A woman who’s lived a bitter and angry life dies and goes to hell. She screams up at St Peter so loudly that he finally pushes open the gates of heaven and says, “Did you ever do one decent thing in your life?” It takes her a few millennia in torment to remember one good deed, but she finally says, “Yes, I once gave an onion to a beggar.” Peter holds out an onion with very long roots. He tells her to hold the root and he will pull her up. The woman seizes the end of the long root and Peter begins to lift her from hell. The other tormented souls see her rise and grab her legs and soon a whole chain of damned is rising with her. The woman is furious–they’ll pull her down. She kicks so hard that the people holding her legs fall off. At which point, Peter drops the onion and she falls back into the pit with the rest.

Anti-immigrant fervor is not new in this country. Anti-Irish mobs attacked incoming Irish in the 1840′s and ’50′s. In the 1884 election, the Republican Party claimed that big-city Irish Democrats were the party of “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion.” Italians came in for their share of ethnic and racial furies, and so it has continued to this day.

But we all came from somewhere else, most by choice, seeking freedom or a new chance, African-Americans against their will, but still wanting and deserving freedom and a new chance.

We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal.

I wonder if that phrase underlies the Supremes recent decisions against women. Justice Scalia said in a speech two years ago that the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equal protection under the laws, doesn’t apply to women. I wonder if the Supremes, the five Catholic men who would have been hounded and pilloried 125 years ago, don’t believe in their heart of hearts that our Constitution exists only for men.

All I can do on this Fourth is pledge my life, my fortune and my sacred honor to make this a country of equal protection under the laws for everyone, female as well as male, Hispanic as well as Irish, Italian, Anglo, Black. It’s a long road ahead, and I often feel such despair that I want to turn away from it, but the thought of my granny and others like her gives me strength for the journey.

Declaration of Independence

June 26, 2014

A Taste of Life, Part One

Click below to listen to author Sara Paretsky read from A Taste of Life. Part 1 of 2.

A Taste of Life, Part One