Sara Paretsky's Blog, page 4

August 16, 2019

If you’d like to catch one of the virtual events connecte...

If you’d like to catch one of the virtual events connected with the Dead Land launch, just click on the links, below.

Door-to-Door with James Rollins, April 15

Women and Children First, April 21

The Raven, April 22

The latest from Sara, Dead Land, will be released April 21, 2020. To pre-order the book, click here.

“As usual, Paretsky (Shell Game, 2018, etc.) is less interested in identifying whodunit than in uncovering a monstrous web of evil, and this web is one of her densest and most finely woven ever. So fierce, ambitious, and far-reaching that it makes most other mysteries seem like so many petit fours.” —Kirkus (starred review)

NBC’s Today show interviews Sara (aired Nov. 3, 2019) on the importance  of narrator selection for audio books in capturing the essence of the character. Here Sara is with Susan Erickson, who does the voice-over for her current VI novels.

of narrator selection for audio books in capturing the essence of the character. Here Sara is with Susan Erickson, who does the voice-over for her current VI novels.

Kate Raphael of KPFA Womens Magazine interviews Sara in an August 12, 2019 broadcast in conjunction with an archived interview with Toni Morrison : Groundbreaking Writers Toni Morrison and Sara Paretsky

Kate Raphael of KPFA Womens Magazine interviews Sara in an August 12, 2019 broadcast in conjunction with an archived interview with Toni Morrison : Groundbreaking Writers Toni Morrison and Sara Paretsky

CrimeReads Lori Rader-Day interviews Sara: Sara Paretsky Writes What’s on Her Mind, discussing white collar crime, her lifelong activism, and the importance of a good editor.

CrimeReads Lori Rader-Day interviews Sara: Sara Paretsky Writes What’s on Her Mind, discussing white collar crime, her lifelong activism, and the importance of a good editor.

On May 9, 2019, Sara received the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s Fuller Award for lifetime achievement at the Newberry Library. Notables in the literary world Lori Rader Day, Ann Christophersen, Dominick Abel, Donna Seaman, Neil Harris, Heather Ash, and Margaret Kinsman, gave moving, and humorous, tributes, highlighting Sara’s myriad accomplishments.

On May 9, 2019, Sara received the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s Fuller Award for lifetime achievement at the Newberry Library. Notables in the literary world Lori Rader Day, Ann Christophersen, Dominick Abel, Donna Seaman, Neil Harris, Heather Ash, and Margaret Kinsman, gave moving, and humorous, tributes, highlighting Sara’s myriad accomplishments.

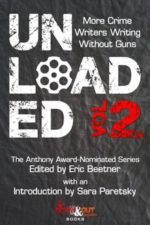

Crime writers have a novel take on reducing gun violence: two dozen short stories of murder without guns. Sara wrote the introduction to Unloaded Vol. 2

Crime writers have a novel take on reducing gun violence: two dozen short stories of murder without guns. Sara wrote the introduction to Unloaded Vol. 2

Sara is honored to receive the first annual G.P. Putnam’s Sons Sue Grafton Memorial Award, presented by the Mystery Writers of America at this year’s Edgars.

Sara is honored to receive the first annual G.P. Putnam’s Sons Sue Grafton Memorial Award, presented by the Mystery Writers of America at this year’s Edgars.

The latest from Sara, Dead Land, will be released Apri...

The latest from Sara, Dead Land, will be released April 21, 2020.

NBC’s Today show interviews Sara (aired Nov. 3, 2019) on the importance  of narrator selection for audio books in capturing the essence of the character. Here Sara is with Susan Erickson, who does the voice-over for her current VI novels.

of narrator selection for audio books in capturing the essence of the character. Here Sara is with Susan Erickson, who does the voice-over for her current VI novels.

Kate Raphael of KPFA Womens Magazine interviews Sara in an August 12, 2019 broadcast in conjunction with an archived interview with Toni Morrison : Groundbreaking Writers Toni Morrison and Sara Paretsky

Kate Raphael of KPFA Womens Magazine interviews Sara in an August 12, 2019 broadcast in conjunction with an archived interview with Toni Morrison : Groundbreaking Writers Toni Morrison and Sara Paretsky

CrimeReads Lori Rader-Day interviews Sara: Sara Paretsky Writes What’s on Her Mind, discussing white collar crime, her lifelong activism, and the importance of a good editor.

CrimeReads Lori Rader-Day interviews Sara: Sara Paretsky Writes What’s on Her Mind, discussing white collar crime, her lifelong activism, and the importance of a good editor.

On May 9, 2019, Sara received the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s Fuller Award for lifetime achievement at the Newberry Library. Notables in the literary world Lori Rader Day, Ann Christophersen, Dominick Abel, Donna Seaman, Neil Harris, Heather Ash, and Margaret Kinsman, gave moving, and humorous, tributes, highlighting Sara’s myriad accomplishments.

On May 9, 2019, Sara received the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s Fuller Award for lifetime achievement at the Newberry Library. Notables in the literary world Lori Rader Day, Ann Christophersen, Dominick Abel, Donna Seaman, Neil Harris, Heather Ash, and Margaret Kinsman, gave moving, and humorous, tributes, highlighting Sara’s myriad accomplishments.

Crime writers have a novel take on reducing gun violence: two dozen short stories of murder without guns. Sara wrote the introduction to Unloaded Vol. 2

Sara is honored to receive the first annual G.P. Putnam’s Sons Sue Grafton Memorial Award, presented by the Mystery Writers of America at this year’s Edgars.

Sara is honored to receive the first annual G.P. Putnam’s Sons Sue Grafton Memorial Award, presented by the Mystery Writers of America at this year’s Edgars.

Dead Land

The latest from Sara, Dead Land, will be released April 21, 2020.

The latest from Sara, Dead Land, will be released April 21, 2020.

Kate Raphael of KPFA Womens Magazine interviews Sara in an August 12, 2019 broadcast in conjunction with an archived interview with Toni Morrison : Groundbreaking Writers Toni Morrison and Sara Paretsky

Kate Raphael of KPFA Womens Magazine interviews Sara in an August 12, 2019 broadcast in conjunction with an archived interview with Toni Morrison : Groundbreaking Writers Toni Morrison and Sara Paretsky

CrimeReads Lori Rader-Day interviews Sara: Sara Paretsky Writes What’s on Her Mind, discussing white collar crime, her lifelong activism, and the importance of a good editor.

CrimeReads Lori Rader-Day interviews Sara: Sara Paretsky Writes What’s on Her Mind, discussing white collar crime, her lifelong activism, and the importance of a good editor.

On May 9, 2019, Sara received the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s Fuller Award for lifetime achievement at the Newberry Library. Notables in the literary world Lori Rader Day, Ann Christophersen, Dominick Abel, Donna Seaman, Neil Harris, Heather Ash, and Margaret Kinsman, gave moving, and humorous, tributes, highlighting Sara’s myriad accomplishments.

On May 9, 2019, Sara received the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s Fuller Award for lifetime achievement at the Newberry Library. Notables in the literary world Lori Rader Day, Ann Christophersen, Dominick Abel, Donna Seaman, Neil Harris, Heather Ash, and Margaret Kinsman, gave moving, and humorous, tributes, highlighting Sara’s myriad accomplishments.

Crime writers have a novel take on reducing gun violence: two dozen short stories of murder without guns. Sara wrote the introduction to Unloaded Vol. 2

Sara is honored to receive the first annual G.P. Putnam’s Sons Sue Grafton Memorial Award, presented by the Mystery Writers of America at this year’s Edgars.

Sara is honored to receive the first annual G.P. Putnam’s Sons Sue Grafton Memorial Award, presented by the Mystery Writers of America at this year’s Edgars.

May 12, 2019

On Losing and on Being Lost

I’m misplacing gloves and bank cards, keys and eyeglasses, with more than average frequency.

I am grateful to Anna Freud for writing the essay, “On Losing and on Being Lost.” She’s writing about grief, and the way it manifests itself in our behavior. During WWII she ran the Hampstead War Nurseries, which cared for children who had been orphaned or otherwise left on their own by the war. After the war, recovering from a life-threatening bout of flu and pneumonia, she had leisure to think about her grief for her father, and the way the children in her care had grieved. She noticed she kept losing commonplace objects, like keys and glasses, and saw how similar it was to the way bereaved children had lost hats or gloves. This was at a time of poverty and need, where it was not easy to replace a hat: everyone paid more attention to their small possessions than we do now.

Freud wrote that children who’d been abruptly separated from caregivers – by their death, or a call-up for active duty – were more likely to lose things than were children who’d had time for a meaningful leave-taking. Similarly, children from angry and abusive families were more likely to lose things. Freud speculated that when we are grieving, we feel (inter alia) abandoned and so we abandon in turn, or assume we will be abandoned in turn, not just by other people but by our belongings.

I know this feeling, this feeling of being adrift, unconnected to people or to the material world. I’m doing my best to carry on, but now, 5 months from Courtenay’s death, I still often feel wrenched by grief.

When I went to the Newberry for the Fuller award, I cried most of the evening. Yes, I was truly moved by the generous praise my friends gave me, but so much of the evening highlighted what I was missing: Courtenay’s constant support for who I am and what I do. Near the end of his life, as he had forgotten many things, he was proud, almost unbearably proud, of me and my work. “I saw how you made those New York publishers pay attention to women,” he would say. “I know what you did.” Of course I keep losing things, my darling one. Of course.

May 11, 2019

Remarks on Receiving the Fuller Award, 9 May 2019

Receiving award from Chicago Lit Hall of Fame Chair Randy Albers

A few years ago, I saw the Oriental Institute exhibit on the history of writing. I felt a sense of awe as I saw myself, one small person, one small voice, connected to a chain of storytellers that stretches almost 6000 years into the past. Buffalo, elk and wolves roamed widely here when the ancient Sumerians made the spoken word visible.

Writing probably developed so accountants could keep track of land and livestock ownership, but it quickly became the purview of poets. And it is to poets, to musicians, to artists that we turn when we celebrate our joys or need help in enduring our sorrows.

We are enduring bleak times, indeed, in these United States, and we need the arts today as we never did before.

In the aftermath of 9.11, musicians from America’s great symphonies went to Ground Zero, where they played through the night to support the hard work of the first responders. No one sifting through rubble for fragments of human bodies wanted to hear someone read an accounts payable list, much less an ideological diatribe. They needed music, they needed poetry.

When you are out of work, or ill, or grieving, you need a sense of an enduring beauty, one that transcends our changeable mortal condition. In these hard times, I turn to the poet Akhmatova, whose work helped her fellow Russians endure Stalin’s tyranny. I turn to the American poet Mary Oliver, whose deep digging into the natural world gives me new ways of thinking, seeing, feeling.

My own most moving moment as a writer came one evening at a reading I’d given here at the Newberry. A group of women stayed after everyone else had left. They told me they were married to steelworkers who’d been out of work for over a decade. These women worked two and three jobs to support their families. They told me they hadn’t read a book since graduating from high school, until they heard that my books take place in their scarred and wounded neighborhood. They came to hear me read, they said, because my words gave them courage to face the hard hand life had dealt them.

That my work spoke to them in such a way does me more honor than I can rightly express. The Fuller award is for me a shorthand for every writer, every storyteller, poet, painter, singer, whose art has helped another person endure the dark night of the soul.

Around 600 BCE, the Spartan poet Sappho wrote, “Although they are only breath/Words, which I command/Are immortal.”

We don’t today know the names of Sparta’s accountants, nor what they had to say about poets and poetry. We know the name of Pericles, a statesman from Sparta’s rival city, Athens, not from his tweets, but because he funded some of the greatest art the world has ever known.

Sappho lived through times as turbulent as our own, but what we remember from those times are not the account books. We remember the poetry and the sculpture. If we want to create a lasting legacy, it will be through the support of that word, the word cherished by every reader in this room, that word which is only breath; in the end, it is poetry which endures.

March 11, 2019

All about the Benjamins

When Rep Ilhan Omar quoted Puff Daddy’s song, I had to have it explained to me – I tend to be clueless aboout pop culture and didn’t realize that it was a reference to the hundred-dollar bill. But I did, sadly, know the trope. Ever since our 9th grade English teacher at Central Junior High reinforced the stereotype of the money-loving Jew in the way she presented Shylock to us as we read A Merchant of Venice, I’ve understood that some part of the world will always view me as though I valued ducats more than daughters.

There were very few Jews in my home town and I was almost always the only Jewish kid in any classroom. I’m not sure how or why I got picked to make presentations on Judaism to some of the area churches when I was 17, but the inevitable question was why Jews were so rich and why we controlled the world’s money. My family struggled like every other to afford a car and a mortgage, but to my audience, all that proved was that we were clever about hiding our wealth from the people around us.

The trope persists, through the halls of Congress, and the pages of Louis Farrakhan’s work. A friend’s sister at a recent party started in on it – my friend pointed at me and shook her head and her sister shut up – I pretended I had heard nothing and seen nothing. I try to be generous with money because I believe that as my physical energy waanes I can use money to do good. But I also worry that non-Jews are judging me in restaurants or occasions for charity

I have nothing to add to this centuries-old libel/slander. I know it will persist long after I’m dead and gone, like so many of the other ills I’ve tried to fight – unsuccessfully. I don’t have much optimism these days. I pretend to, I pretend to rejoice in the energy of the youth around us – but when our energetic youth carry so much old baggage with them, I don’t have a lot of hope.

January 13, 2019

Do-Overs

I replay my past with anguish over my failures – my biggest – my hot temper which bubbles over when I suffer a narcissistic wound. Every time it happened I was ashamed in the aftermath, vowed not to do it again. In time I learned some patience, some cooling off before reacting, but never enough.

When I think of Courtenay’s last days, I suffer a different self-torment – that I wasn’t physically with him – not at the moment of his death, but in the days before, where I came and went.

I’ve been hearing from other grieving people since Courtenay died. Some are close friends, some are strangers, but all experience the same torment I do, the “if only” torment.

I admire Kate Atkinson as a writer, but when I read her 2013 Life After Life, it irritated me exactly that reason – the effort to rewrite a personal as well as a meta life. You could do it differently, you could affect the outcome – if only someone had killed Hitler (or, for that matter, Stalin) before 50 million people were murdered. If only you’d stayed home instead of going into town and contracting influenza. If this, if that. It seemed to me at the time to be unbearably juvenile, even while beautifully structured and written. Today it hits me even harder.

Ten years ago, if I’d been offered a chance for a do-over, it would have been for some missteps I took that harmed my public career. Now – I’d redo those last two days. Or the time I screamed my head off in traffic. Or – or – or.

The point is, if you were given one do-over, you’d always pick the wrong one. And then you’d spend your time wanting a do-over to change your choice.

January 10, 2019

The Quotidian

The quotidian does me in. I love to sing, although my musicianship can charitably be called “sketchy.” Courtenay loved listening to me. When I took lessons or sang in a community musical he always came to hear me perform. Similarly when I did readings or gave talks. Last night I went to the choir practice for my local synagogue. I’d never been part of it; in fact, i didn’t know it existed. On the way home I had a total meltdown. I kept thinking, I have to get control of this or I’ll hit someone and then I’ll cause wider floods of grief for strangers, but I couldn’t stop weeping.

Grief surges are like power surges. They overwhelm the system, the trigger all the circuit breakers. They do us in.

December 29, 2018

And now – bewilderment

I struggle to be in the now. I was with Courtenay for 47 years and we had the usual trajectory of excitement and its physical passions, moving to a sense of belonging together and then building a life together, but that life feels remote, almost non-existent. At this time, the past is a series of self-lacerations – the things I didn’t do, the attention I didn’t pay, the carelessness of feelings/time/person. I want to connect to the whole arc of our life together, the excitement, the quotidian, the annoyances, but instead those years seem more remote, unreal, than if I’d read a novel about them.

It’s easy to turn from that uncertainty to the future – many of us live there most of the time – the next event, the plan for the next trip/project. But my stomach tells me it’s important to resist the pull of the future. My stomach says to stay in the now if I can.

December 14, 2018

The Journey So Far

Courtenay died on November 22 at 9 in the morning. He was in a hospice facility, where he’d been for a scant 53 hours. I was not with him. That is a source of pain.

On October 2, I wrote in my journal that he’d been ill, another lung infection – pneumonia? a worsening of his CPOD? – but that prednisone and antibiotics had brought him back. I wrote that I had arm-wrestled the Angel of Death, who had let me win, as he had many times in the past 17 years. “I know you could win any time you wanted,” I wrote to the Angel. “I know it’s an illusion that I have won, but I am grateful.”

The seven weeks that followed were a steady decline, just one I refused to acknowledge. Or perhaps I thought the Angel would keep letting me walk away from the table with another victory. On November 18, my poor darling lost power in his legs, but he was agitated and couldn’t stay still. I finally, on the 20th, agreed to hospice care away from the home he’d lived in for 61 years. The hope was that medication would calm his agitation and he could return to the house he loved.

The hospice nurse called and said, “I’m sorry to tell you that Courtenay made his transition.” I knew as soon as I saw the number on the screen that he had died, but the phrasing was so strange I didn’t instantly understand it. Then I screamed, “No, no, no,” even while I started pulling on outdoor clothes. Leashed the dog, texted his sons, called Marzena, who loved him like a daughter . We met in his room at the hospice center. The next 4 hours are not a blur but they are painful and private. We had to move his body out by 1 p.m. because of the rules of the hospital where the hospice is housed. We were greatly aided and supported by the hospice staff, who let us stay with him, holding him, until the last possible moment. They escorted him out with gongs, with psalms, with the Mozart clarinet concerto. I wanted to fling myself on the body and scream and tear myself apart, but could not.

We had a funeral service on the 25th, Jewish, in our home. Beautiful and overwhelming. Courtenay’s favorite poem, Mary Oliver’s “When Death Comes.” So true to him: “a bride, married to amazement, the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.” My own favorite: A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning. “Our two soules, therefore, which are one, though I must go, endure not yet a breach but an expansion.” My beloved Eve read that, a heroic effort to make it through to the end without breaking down.

It turns out there is no pre-mourning. Over the last 5 years, he gradually lost many of his great capabilities, the problem-solving, the insights, the understanding of General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics and how they are at work and play in the natural world that surrounds us. He became bewildered by simple things and there was so much loss that I thought the ultimate loss would not be so devastating. There is no pre-mourning. The ultimate loss is still a grand piano that drops from the sky onto one’s head.

I have a shrine in the living room: his ashes with emblems of his loves – a photo of him with one of the dogs he adored, the Go stones for the game that was his passion, pool balls – another passion. (Two weeks before he died he did the equivalent of running the table in the arcane version of billiard-pool he and his friends played). I still need something to signify his love of ships and sailing. I figure the room is full of photons and electrons. I talk to him at the shrine.

I walk the lakefront with the dog, who was inseparable from him for four years and is as bewildered as I am. I watch the ducks in the cold water, the grey air, and take solace in knowing that I am connected to a web of nature, of plants and animals where we all keep going, putting one little webbed foot in front of the other, valiantly braving the cold.

It turns out mourning is physical. It is exhausting, but one feels it in the body. In my case, it’s a heaviness in the stomach. When I imagine going shopping, or traveling, or any of those things, the heaviness increases and tells me to stay put.

The least thing can make the chest constrict. Also I am bewildered: I want him here, but memories also stir the more recent griefs: he was the most competent man I ever knew, the most moral, the kindest, the most brilliant but in the last years he relied on me to mediate every aspect of the surrounding world. It was never a burden but it was always a grief.

I am on an express train moving at too fast a rate from the place I want to inhabit, the world where the Angel of Death let me keep winning our arm-wrestling matches. People in my house for the last 8 days interrupted my grief and I am angry that I let those precious days close to the station be taken from me.

I have always hated my legs – they look fat and wobbly. Almost every day for 47 years, Courtenay said to me, “You have beautiful legs.” At the hospice, I lay in bed with him, holding him, singing the ballads he loved. The last words he said to me were, “Your voice is lovely and your legs are beautiful.”

He never in 47 years complained of pain, despite crippling RA, a leg broken in 7 places, cancer and radiation therapy. He never wanted novocaine when getting dental work, no nerve blocks when he needed hand surgery. The last 4 days the pain was too great for his stoic heroic heart. I should have stayed with him, holding him, but I did not. I was the bustling Martha, trying to set up in-home care, imagining he would come back. I was walking the dog and writing emails and not knowing I should not have left his side. That is a pain I can hardly bear.

The journey so far.