Sara Paretsky's Blog, page 7

December 15, 2015

Dirty Deeds in the Cornfield

Dead End

The sun was setting when Peppy and I drove east of town, looking for Doris McKinnon’s farm. I’d spent a tense two hours at the hospital, but had finally received a reassuring report on Ms. Albritten—Nell, I’d learned when I went through her wallet looking for her Medicare card.

I’d seen Albritten into the emergency room, and made sure she was getting priority attention, before checking in at the front desk. The ambulance driver was standing there; t turned out he was the same person who’d come for Sonia Kiel twelve hours earlier—he was working double shifts this week.

“Are you with some kind of Guardian Angel organization?” he demanded with heavy humor. “You go through the streets of Lawrence looking for ladies who’ve keeled over?”

“Hard to know what you would do without me,” I said, trying to get into the spirit of the exchange.

Actually, I was tense. Say a little scared. I was in a strange town with a woman who had a bitter history with the place. If something I’d said or done pushed her over the brink, I would be in a lonely spot.

Albritten had never lost consciousness. She’d thrust her pocketbook and phone at me as she was wheeled past, making the crew stop to watch me lock the door before she let them put her in the ambulance.

“Better you than them. At least I’ll know who stole my money if it disappears,” she said to me..

I followed the ambulance to the hospital. While I was filling out forms for them, I went into Albritten’s phone. Her son’s number was fortunately one of seven numbers in her favorites screen. It unnerved me when he answered the call with, “Yes, Mama?” but of course her name had shown up on his own phone.

He lived in Atlanta, he said, when we’d sorted out who I was and why I was calling. He demanded to speak with the doctors. I explained who he was to the people at the intake desk. After some back-and-forthing with the emergency room team, the intake head told Todd the doctor would call him soon, but right now was taking care of his mother and couldn’t be interrupted.

“Just who are you, though, and what were you doing with Mother?” he said, when they’d given me back the phone.

“Do you remember Emerald Ferring?” I didn’t say I was a detective, just that I had come from Chicago looking for her, and a neighbor had directed me to Ms. Albritten.

“She was in the middle of telling me about the farm where the Ferrings moved back in 1951 when she suddenly collapsed.”

“She’s never had heart trouble,” he said. “Nothing wrong with her health. What else went on? Was she agitated? Did you try to get her to do something she didn’t want, like sign over the title to the house? It’s in my name, so you’d be out of luck.”

“No, Mr. Albritten.” My lips were stiff: this was the kind of accusation I’d been afraid of. And it’s a sadly common scam these days, vermin preying on the elderly. “When you talk to the doctors, see if they’ll let you speak to her.”

When he’d finished worrying and accusing and decided he needed to book his flight to Kansas City, I called Lotty Herschel in Chicago. It was mid-afternoon, when she’s usually at her busiest, but she let her clinic nurse put me through to her. I’d texted her a few times from the road, but we hadn’t actually spoken since I left Chicago on Tuesday.

“You did the right thing, Victoria,” she said. “Get the doctor’s name; I’ll call him later this afternoon. Try not to worry; you couldn’t do more than what you’ve done.”

I sat in the waiting area, trying not to worry. I tried to occupy my mind with reports for clients in Chicago, but the city, and my life there, seemed as though they belonged to some movie I’d watched years ago. I couldn’t remember the details or why they should matter to me.

I had several urgent texts from Troy Hempel. Did you find Ms. Emerald? What did the woman you were speaking to tell you?

She’s in the hospital; I’ll let you know if she’s able to tell me anything. I leaned back in the uncomfortable chair and tried to concentrate on my breathing and not on the yammer of the television. It seems as though one of the torments of modern medicine, besides incomprehensible bills, endless waits on phones and waiting rooms designed to serve as better, and outrageous drug prices, is the constant blare of a television in every room.

“Have her parents been to see her?” I asked.

There had been no visitors, although a man had called around noon to check on her; one of her brothers, the nurse thought he’d said.

At length one of the interns came out to give me good news about Ms. Albritten: all her cardiac signs were stable. They would keep her for twenty-four hours to monitor her, but she should be fine. Yes, I could go back for five minutes to give her her phone and handbag in person.

She was dozing: even the strongest-hearted old woman gets worn out by an ambulance ride and an hour of poking and x-raying. They’d given her some kind of sedative, so that when I gently touched her arm she stared at me with puzzled eyes.

I reminded her that we’d been speaking about Emerald Ferring, that I was in from Chicago looking for Ferring.

Albritten tried to struggle upright. I pressed the buttons on the side, but a nurse who’d been hovering outside the cubicle came in.

“No disturbance for you, Ms. Albritten.”

“One thing,” Albritten said through narcotic-thickened lips. “What I say ‘bout Emral’?”

“That she and Lucinda had moved out to Doris McKinnon’s farm east of town.”

“I say ‘bout McKi—Kin?”

“No more,” the nurse said, taking me by the arm.

“Need know,” Albritten insisted.

“You said she was a white woman who rented to black students. You said you hadn’t seen her for years. And then you collapsed.”

Albritten relaxed into the bed and shut her eyes. “S’right. Not see. Long time.”

The nurse nodded significantly toward the exit. I bent to assure Albritten that her son would be arriving the next day, and a corner of her mouth twitched into a smile.

Before leaving the hospital, I made my way to the intensive care unit. I identified myself to the charge nurse as the detective responsible for getting Sonia Kiel and Naomi Wissenhurst to the ER last night.

“Oh, yes, Detective. We were able to release Naomi: she needs medical attention but can get that at home: she’s taking a leave of absence from the university for the rest of the term. Sonia is still unresponsive, but of course she was in worse shape before she took the drugs and at least she is able to breathe on her own. The next twenty-four hours will be important.”

“Have Sonia’s parents been here?” I asked, curious. “Or anyone from St. Rafe’s?”

“A man phoned this morning; I think he said he was one of her brothers, but you’re the first person who’s actually come here. Would you like to see her?”

She led me into the back, where Sonia seemed like an appendage to the computers surrounding her. Her breathing was slow and shuddery: at the end of each exhalation there was a dreadful pause as if she weren’t sure she should start up again.

They’d bathed her, of course, and put her into a clean gown. Her face was slack, so it wasn’t easy to imagine what she would look like if she were awake and animated, but in repose she seemed to have her father’s square face and dark coloring. Lenore Kiel’s hair was thin and dirty blond, Nathan’s thin and white, but perhaps when he’d been young he’d had the same wiry black curls as his daughter.

Drugs and street life had coarsened Sonia’s skin. She had some old bruises on her arms, but I didn’t think they were track marks, more as if someone had hit her. Someone at St. Rafe’s or someone on the street?

I picked up one of her flaccid hands between my own and knelt to talk to her. “It’s V I Warshawski, Sonia. You called me this morning, to say you’d seen Emerald Ferring. You saw her on Matt Chaleff’s grave, you said. Matt Chaleff.”

I thought she might have twitched when I repeated his name, but it was probably wishful thinking.

“If you wake up, when you wake up, you call and tell me where he’s buried. I want to see Matt’s grave, okay?”

I held her hand a bit longer, massaging it lightly. Her fingers were rough, the nails cracked. An obscure impulse made me brush the curls away from forehead. When had her mother last touched her like that?

The nurse gave me an approving nod as I left. “The LPD should send you over when they need to question a patient; you have a good touch.”

I smiled in embarrassment. “I’ll talk to Sergeant Everard about it.”

I was glad to have Peppy with me as I rode out of town. The people I was meeting, the histories I was learning, were dragging me down. My friends were six hundred miles away. My lover—ex-lover? I still hadn’t heard from Jake—was even further. The countryside was desolate in the November twilight. Whatever farmers do in the fall must take place indoors. If I’d been by myself the desolation might have made me drive straight into the Kansas River.

My iPad showed the McKinnon farm about half a mile south of the highway between Lawrence and Kansas City. Once I left the highway, I was on gravel roads that didn’t have streetlamps. I drove slowly, keeping to the center of the road, headlights up.

At one point, showed up on my tail, a dark SUV, maybe a Buick Enclave. I thought I’d seen it as I got on the highway, but the traffic was heavy enough that I couldn’t be sure. Here on the county roads, we were alone. The hair on the back of neck prickled. Peppy, sensing my unease, stood , growling lightly.

At the crossroads between East Nineteen Hundred and North 2800 roads, the SUV turned south, where a sign pointed to the Kanawaka Missile Silo. I went north, my shoulder muscles relaxing, breathing easing back to normal.

After following North 2800 Road for a quarter of a mile, I came to a turnoff with a mailbox labeled McKinnon. Excellent.

The drive ended in a turning circle about a hundred miles from the road. I pulled up behind an elderly Honda and looked at the house. It was a square building, two stories and an attic, and it wasn’t just dark, but gave off that aura of emptiness you get from an abandoned building. I hadn’t taken the time to search McKinnon before I drove out; maybe she’d died and Nell Albritten hadn’t heard about it.

I got out, releasing Peppy from her leash. The dog tore off into the twilight, after who knows what Kansas animal: I hoped not a skunk. I shone my flash over the ground and the out-buildings—two barns, some sheds.

If Emerald Ferring and August Veriden had come out to see Doris McKinnon, they must have turned back and driven on. This was a complete dead end.

Peppy had raced back from her hunting adventure but had started nosing around the house, snuffling at the foundation. She disappeared again, this time at the back of the house. I called to her, but she started barking and whining.

“Come!” I said in my sharpest voice.

She came partway toward me, a darker shape in the dark night, but barked and whined again and turned back to the house. I followed her, my legs stiff, the tingling on my neck moving down my spine.

The back door was shut but not locked. Peppy can smell ten thousand, or maybe it’s ten million times better than I do, but when I pushed the door open, even my inferior nose picked up what she had noticed from across the field—the sickly-sweet smell of rotting flesh, the metallic odor of blood.

December 6, 2015

Happy Hanukkah

Hanukkah starts at sundown on December 6. It’s sometimes called the Festival of Lights because we light candles every night for eight nights–starting with one, ending with eight. Some people eat fried food to commemorate the miracle of the oil in the Temple: a flame was supposed to be lit constantly in front of the Ark of the Covenant. Growing up in Kansas, I was always the only Jewish kid in my class. I told the story of Hanukkah so many times I never wanted to tell it again, so this is the short version. You can read a longer version here:

Hellenized Syrians had conquered the land of Israel and turned the Temple into a shrine for the Greek gods. They demanded that Jews give up their own beliefs and bow down to Zeus. When the Temple was reclaimed from the Greeks, legend has it that there was only enough oil to burn for a day and a night, but while messengers were scouring the land for another supply–which took eight days to arrive in Jerusalem–the little vial kept burning. And so we light candles and fry food. Hmmm.

Chiara’s First Hanukkah

In the context of today’s extremism in just about every religion, including Judaism, Islam, Christianity, and even the Buddhists in Burma, parts of the story are troubling. Historians say that the Hasmonean brothers, who drove the Greeks and their idols from the land, installed a ferociously rigid version of Judaism, and punished, even killing people who didn’t live up to their version of the religion. On the one hand, the Hasmoneans were heroic: they valiantly stood up to and conquered a much larger invading army, they protected the right of their people to worship as they chose. On the other hand, once in power, they were rigid and punitive.

Despite this troubling history, Hanukkah is a time for acts of bravery, even small acts. Jews are encouraged to set their Menorahs in a window where they can be seen. In some parts of the world, even in some parts of America, it can be hard to be a Jew. It takes particular courage to make a public declaration, to show that very Jewish symbol to the world.

This public declaration for me means I must start to take a more visible stand on the issues that matter most to me in today’s America, in particular, reproductive rights. Like many supporters of women’s right to make their own health and reproductive decisions without church or state interference, I’ve let myself be silenced by the inflammatory rhetoric of those who think we are children (or even chattel animals: the Illinois legislature assigns women’s health to their agricultural livestock committee). Yesterday I stood with Planned Parenthood on Michigan Avenue. I continue to stand with them.

I stand with Planned Parenthood

November 18, 2015

BRUSH BACK named one the best thrillers of 2015

The Washington Post named BRUSH BACK, Sara’s most recent novel, one of 2015’s top 5 thrillers.

The Washington Post named BRUSH BACK, Sara’s most recent novel, one of 2015’s top 5 thrillers.

November 3, 2015

Sara receives Paul Engle Prize

Sara received the 2015 Paul Engle Prize, recognizing both her body of work and her work for social justice. See her in conversation with Maureen Corrigan at the Coralville Public Library here.

Sara received the 2015 Paul Engle Prize, recognizing both her body of work and her work for social justice. See her in conversation with Maureen Corrigan at the Coralville Public Library here.

Sara reviews Peter Ackroyd’s “Wilkie Collins,” a biography of one of the fathers of detective fiction, in the New York Times Book Review, October 30.

July 23, 2015

Sara appears on BBC Radio’s Woman’s Hour

While Sara was on tour in the UK, she appeared on the Woman’s Hour, one of the most listened to programs on BBC Radio. Listen to her interview here.

While Sara was on tour in the UK, she appeared on the Woman’s Hour, one of the most listened to programs on BBC Radio. Listen to her interview here.

June 26, 2015

Sara interviews with the London Times’ Crime Club

In their new crime fiction monthly newsletter, The London Times’ Crime Club asks Sara about V I, where she came from, and how she’s changed over the years. Read the interview here.

In their new crime fiction monthly newsletter, The London Times’ Crime Club asks Sara about V I, where she came from, and how she’s changed over the years. Read the interview here.

Sara interviews with Crime Club, the new London Times crime fiction newsletter

June 11, 2015

Boom-Boom Warshawski Makes his Chicago Blackhawk debut

Stanley Cup playoffs, Blackhawks and Lightning tied at two games each. How Boom-Boom Warshawski, Blackhawk star as well as VI’s cousin and closest childhood friend, would have loved to be in the middle of the fight!

My second novel, Deadlock, introduced Boom-Boom, although he sadly entered the series as a murder victim.

Deadlock, a V I Warshawski novel

Over the years, VI has often thought about Boom-Boom and recalled some of their more hair-raising adventures together. In Brush Back, on sale out in July, Boom-Boom plays a major part of the backstory. I originally had planned to open the novel with a flashback to his Blackhawk debut, but as the story worked out, I had to remove that opening chapter. (By the way, you can pre-order Brush Back now by following the link.)

With Stanley Cup mania going on, I thought it might be fun to share this outtake chapter with you:

Blackhawks win Stanley Cup

Prologue

Up near the rafters the noise shook our bones. We were on our feet, slamming our chair seats up and down, stomping, screaming, whistling.

“Boom Boom!” slam. “Boom Boom!” slam. “Boom Boom.”

The foghorn under the scoreboard bellowed. Down below us, on the ice, my cousin raised his stick from the middle of the scrum, then skated to our side of the rink. Of course he couldn’t see us, with the stadium lights in his eyes, but he bowed in our direction.

Frank Guzzo hugged me so hard we both almost toppled into the seats below us. Mayhem in the Madhouse on Madison: Boom Boom’s first game as a Blackhawk, his first goal, his first victory.

Frank shouted something at me, but I couldn’t hear it, even with his lips near my ear. I screamed back, but our words were swallowed by the sound. The old Chicago Stadium, decibel level around 130 on average, up to 300 when all noise-makers were turned on.

Old Chicago Stadium where Boom-Boom (and MJ, and Bobby Hull) played

We followed the rest of the crowd down the steeply-banked stairs and went to wait by the player exit. It was April, near the end of the regular season, a warm enough night that none of us put our jackets on. My dad and his brother Bernie were grinning at each other like teenagers and the rest of us were teenagers, or near enough.

Boom Boom had spread tickets around like confetti, to me (of course) and his folks and my dad, his best friend Frank Guzzo, even to some of his lumpy cousin’s on his mother’s side. Another couple of dozen people from the neighborhood had paid their own way: this was going to be a night to tell their grandchildren about: I was there when Boom Boom Warshawski scored the winning goal against the Flyers.

Boom Boom had even given Frank a ticket for his sister Annie, who was still in high school.

“I don’t know where she is,” Frank said, when I asked. “I just drove in from Nashville for the game. You remembered to get the ticket to her, right? You haven’t become so snooty at Red U that you forgot your old pals, have you?”

Red U. That was an old insult for the University of Chicago, dating to the Nineteen-fifties, the McCarthy era, long before my time on the quads. It’s what all our neighbors called it in South Chicago, though, and it added to the hostility toward my mother when they learned she had her heart set on my studying there.

I punched Frank in the ribs. “I’m slumming with you, aren’t I? I hand-delivered the tickets. Your mom said Annie wasn’t home so I left the envelope with her, okay?”

“Warshawski!” Frank saw my cousin before the rest of us. “You dang hotdog, you. You trying to upstage the Golden Jet?”

Boom Boom laughed. “No way, man. Lucky shot. Not like that homer of yours against Nashville on Monday.”

“Yeah, speaking of which, I gotta head out now. I’m already running a ninety-dollar fine for being AWOL, can’t make it two days in a row.”

Boom Boom walked across the parking lot to Frank’s car with him, tripping on the deep grooves in the gravel. “Your turn’s coming, Frankie, your turn’s coming. When they call your name in the starting line-up at Wrigley, I’ll be there hollering, you’d better believe it. Thanks for making the trip up here, man.”

Frank Guzzo, Boom Boom Warshawski—they were the biggest stars of my neighborhood. When they graduated high school three years earlier, the school held a day in their honor. They were given special plaques, they got to choose the menu in the cafeteria, the gym was renamed the “Guzzo-Warshawski Gym.”

All over this city, poor kids dream of becoming sports legends, but Boom Boom and Frank were the rare boys who got to live the fantasy, Boom Boom on ice, Frank in baseball. Two years after Boom Boom’s debut—when my cousin had already turned into a legend of sorts—Frank was called up to Wrigley Field. The same crowd that had gone to see Boom Boom turned up for Frank.

All those hardcore White Sox fans who’d sooner spit than say “Ernie Banks” made the long L-ride north to cheer the home boy. I was in my first year of law school then, but I blew off a paper to join my dad, Boom Boom, my dad’s police buddies, and my uncle Bernie in the bleachers.

VI and Sara in front of Wrigley Field

His third game at Wrigley, Frank’s turn ended. The Cardinal second baseman, leaping to get the catcher’s throw, came down hard on Frank as he was sliding into second. The Cardinal’s cleats ripped muscle from bone. Frank had a half dozen surgeries, two years of rehab. When they were finished with him, Frank still had an arm better than anyone on the south side, but nowhere near good enough for Major League ball.

Cardinals v Cubs

My cousin’s been dead a lot of years now and so has my dad. I don’t hear news from my old neighborhood very often and I’d almost forgotten Frank. Until the day he walked into my office.

June 6, 2015

Brush Back receives 3 starred pre-publication reviews

Brush Back has received four glowing pre-publication reviews, including three starred reviews—not an easy feat. Pre-order and read an excerpt now and to find out for yourself what makes Brush Back V I’s most thrilling installment yet.

Publisher’s Weekly (Starred Boxed Review)

South Chicago provides the setting for MWA Grand Master Paretsky’s electrifying 18th novel featuring PI V.I. “Vic” Warshawski (after 2013’s Critical Mass). Vic thought she had left her old neighborhood—and her former teenage flame, Frank Guzzo—years ago, until he approaches her with a sensitive issue: his mother, Stella, just finished 25 years in prison for murdering Frank’s younger sister, Annie, and she’s now proclaiming her innocence. Reluctant to get involved—Stella always hated the Warshawski family—Vic agrees to look into the matter, but is floored when Stella accuses the detective’s beloved late cousin and Chicago hockey legend Boom-Boom (who was murdered in 1984’s Deadlock) of having a hand in Annie’s murder. Determined to clear Boom-Boom’s name, Vic throws herself into the investigation, which takes her into the murky political waters of her former stomping ground, with its back channels leading to the state’s highest echelons of power. Paretsky never shies from tackling social issues, and in this installment she targets political corruption without ever losing sight of her dogged sleuth’s very personal stake in the story.

Booklist (Starred Review)

In an unlikely moment of sentimentality, Chicago private investigator V. I. Warshawski grudgingly agrees to spend a few hours investigating the possibility that her old friend Frank Guzzo’s mother, Stella, was wrongfully convicted of murdering her daughter, Annie, 25 years ago. Stella, a nasty piece of work known for battering her children and slandering V. I.’s mother at every opportunity, punches V. I. at their first meeting, and Vic resolves to dump the case. But, then, Stella makes public claims that Annie’s long-lost diary implicates V. I.’s beloved hockey-star cousin, Boom Boom Warshawski, in her murder. No way is V. I. going to let those accusations stand, and she’s off fishing for new evidence from those involved in Annie’s case. As intrepid and tenacious as she was in the series’ first novels, V. I. battles the circled wagons of the tight-knit South Side Chicago neighborhood in which she grew up, which ultimately reveals

a satisfyingly complex story of decades-old murder, family loyalties, dirty politics, and gangsters. A certain summer hit, this robust series entry harkens back to the outstanding Fire Sale (2005), which also returned V. I. to her roots. HIGH-DEMAND BACKSTORY: V. I. Warshawski remains one of the most-loved characters in crime fiction, and this episode, drawing as it does on Warshawski’s personal history, will be of particular interest to fans looking for backstory.

Library Journal (Starred Review)

Paretsky’s latest V.I. Warshawski novel (after Critical Mass) finds our intrepid Chicago private investigator doing a favor for old high school boyfriend Frank Guzzo. Back in the South Side neighborhood, the Warshawski clan and the Guzzos have a long-standing and seemingly inexplicable feud, but V.I. reluctantly agrees to look into an unlikely claim that Stella, Frank’s mother, was framed for the bludgeoning death of her daughter Annie 25 years ago. But Stella’s tactics turn on the Warshawski family, and V.I.’s famous cousin, Boom Boom, is implicated in the case on the word of a volatile and still violent 80-year-old woman. Against her better judgment, V.I. pursues the case, raising the hackles of her lawyer, her reporter friend who relies on her tips, and an assortment of friends and family readers have come to know. VERDICT Paretsky’s novels are never boring, but this one is particularly well executed, combining family and city history with local political intrigue and a jaunt into the tunnels under Wrigley Field. The author’s many fans won’t be let down, while readers new to the series will be able to follow the story line without difficulty.

V.I. Warshawski (Critical Mass, 2013, etc.) takes on the most thankless task of her career: reopening a 25-year-old murder case on behalf of a convicted defendant who hates the sight of her. When trucker Frank Guzzo, who was once V.I.’s high school boyfriend, tells her that his mother, Stella, claims she was framed now that she’s been released after doing a quarter-century for beating Frank’s sister, Annie, to death, V.I.’s main reaction is skepticism. Who knows if Annie was really still alive when Stella left her to play bingo? In the end, though, she agrees to ask around, and the first person she questions is Stella. She quickly learns that Stella still blames V.I.’s mother, Gabriella, Annie’s piano teacher, for turning her daughter against her, and V.I.’s late cousin, hockey star Boom-Boom Warshawski, for ruining Frank’s chances of playing with the Cubs. She also learns that Stella swings one mean fist. Clearly this isn’t a client she can work with. But every attempt she makes to extricate herself from this sticky case enmeshes her more closely with all Paretsky’s trademark complications—bullying cops, crooked politicians, long-simmering resentments, buried secrets avid to spring back to murderous life—and she’s haunted by Stella’s contemptuous charge that “you want this to be about my family, but you won’t admit that it’s really about yours.” A healthy dose of present-day murder drives home the urgency of V.I.’s quest. Tension spikes when Boom-Boom’s goddaughter, hockey player Bernadine Fouchard, who’s been staying with V.I., goes missing. Paretsky, who plots more conscientiously than anyone else in the field, digs deep, then deeper, into past and present until all is revealed. The results will be especially appealing to baseball fans, who’ll appreciate the punning chapter titles and learn more than they ever imagined about Wrigley Field.

May 20, 2015

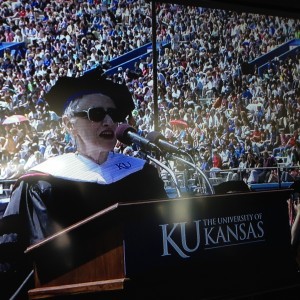

KU Commencement Address, May 17 2015

I was privileged to receive the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters and to address the graduates at the University of Kansas on their May 17 2015 Commencement.

Delivering Commencement Address

Remarks for the University of Kansas 2015 Commencement

Chancellor Gray-Little, Chairman Wilk,Distinguished Guests and Faculty. Above all, members of the Class of 2015 and your happy families: welcome, and thank you, for the honor of this degree and the privilege of speaking here today.

Congratulations to all our graduates. You completed a rigorous course of study, despite times of despair or frustration or confusion. Whatever the next stage on your journey, when you are discouraged and feel like quitting, remind yourself that you stuck with this job, this important job of education, even when the going was rough.

Let’s have a round of applause for our courageous class of 2015.

With Chancellor Gray-Little, Prof Ada Sue Hinshaw and others

While we’re in the clapping mood, let’s also thank the families and friends who made sacrifices so that these graduates could stay the course.

I have been a Jayhawk since I was five years old, when I attended my first KU commencement. My dad had just joined the Kansas faculty and he took part in the procession through the Campanile and down the hill. My mother and brothers and I stood in the stands and cheered when we saw him.

AI grew up around this university and received my BA here. My years on the hill shaped who I have become as an adult. Like most alums, I go insane during March madness, feel a little more depressed when football seasons rolls around.

Reading in a children’s cubbyhole in the Lawrence Public Library

Of course, university education, your education, your life, are about more than cheering for sports teams. As a fan you are on the sidelines, but you are the key players in your own lives. You will spend those lives in your own fields of endeavor—almost always without a cheering section. You will be tested time and again, and you will find yourselves needing to draw on the lessons you learned here.

Although commencement literally means to begin, it is also a time of endings. All endings are hard—they are the hardest part of a novel to write well—so it shouldn’t startle you if you find the end to your KU life difficult. Moving on to the next stage of your journey means taking a leap from the high dive without knowing what kind of water lies below you.

For those of you who do know what you are doing next, whether at work or school, or as a volunteer, my heartiest congratulations. For those who are facing the future with less certainty, you are not alone. If it’s any comfort, after my own graduation I floundered in clerical jobs, sold computers to insurance agents, wrote speeches for corporate executives, and did many other odd jobs for a good number of years before finding my way to my public writing voice.

It is not always given to us to find our passion or our path easily. I can’t promise that your own road will be easy, but I can promise this: if you give up, you will never find the road at all.

You are graduating into a world that will challenge you in many ways. You face financial and job uncertainties tougher than my generation knew. You also face opportunities we didn’t have—those of you born with earbuds implanted in you roam the fast-changing technology landscape more easily than my generation does.

At the same time, you came of age in a world dominated by war, by terrorism and by economic instability. The first years of the 21st century could be called the Age of Fear, starting with fear of terrorism, and moving from there to fears closer to home.

Hand-in-hand with fear goes the extraordinary rage with which people around the globe confront each other. Here at home, we hurl abuse at each other from opposite sides of a deep political divide. We then retreat to the safety of our favorite Internet sites, where we stoke our rage by writing ever more monstrous accounts of what those other folks, those barely human beings, are doing.

Not since the Civil War has our country been such a house divided. Yet it was in the midst of the Civil War, that bloody conflagration, that the University of Kansas was founded. In 1863, two weeks before Lincoln spoke at Gettysburg, while war was still raging, the Kansas legislature voted to establish a university in Lawrence, provided the town could supply land and money.

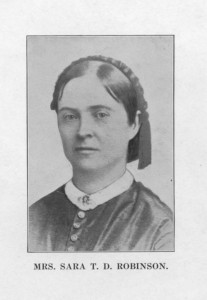

Sara Robinson and her husband Charles, who gave up an affluent life in the east to make sure Kansas came free into the Union—even spending time in prison at the hands of slavery forces–, deeded the land where we stand today. Amos A. Lawrence, a town founder, donated most of the money. In 1866, the first classes met, an equal mix of young men and women—virtually unheard of in that era.

The university’s founders had a bedrock belief, bred in their very bones, that education was essential for good government and good citizenship. The first thing the Puritans did when they reached Massachusetts was to set up public schools, because they knew that their future depended on an educated citizenry.

Sara Robinson, 1827-1911

The men and women who came from New England to settle Kansas two centuries later didn’t know how or when the Civil War would end, but they, too, knew they needed to educate the next generation of citizens if the Republic had any hope of surviving. Charles and Sara Robinson took a great leap from that high board when they gave the university the land we stand on today, even though only a few months earlier, terrorists from Missouri had massacred most of the men in Lawrence.

Our founders chose as the motto for our school the verse from Exodus, when Moses says: I must turn aside to see that great sight, why the bush burns but is not consumed.

The ability to look at the unknown, the startling, the terrifying, and to ask fundamental questions about it, lies at the heart of our Kansas education.

If you take nothing else away with you, take this: an abiding spirit of inquiry.

Questioning, listening, learning are the true antidotes for fear. FDR said we have nothing to fear but fear itself, but I believe the biggest thing we have to fear is willful ignorance. Willful ignorance, and a desire to give way to unthinking rage lie behind today’s terrorists in Africa and the Middle East, who bomb schools and whose name translates as “Down with western education.”

Willful ignorance also catches up with us here at home. Every time a state government slashes education budgets—and states all across the Union are making deep cuts to education–I weep: governments are sacrificing the long term health of the Republic for very minor fiscal savings.

The spirit of open-minded inquiry is how change happens for good, in our individual lives and in the larger world. The book of Exodus would tell a different story if Moses had seen the bush and said, “oops, scary fire, think I’ll take my sheep a different way,” or even worse, if he’d been texting and hadn’t seen the bush at all.

The inquiring mind, the open mind, lies behind every discovery that changes lives for the better, from Arthur Fleming noticing the mold in his petri dish and turning it into penicillin, to Rosalind Franklin noticing the double helix in X-rays of DNA, which opened the field of modern genetics.

Learning to question, rather than to fear, isn’t something you get from Google. You definitely don’t get it by building walls of pre-judgment and anger around you. You learn by digging deep—by understanding the minds of the people you work with, understanding the deeper issues underneath the surface tweet.

We humans all live both alone, and in community. If this age could be called the Age of Fear, it could equally be called the Age of the Selfie.

We live in isolation inside our earbuds, but we inhabit shared space, and it is space we hold in trust for those who follow us. The founders of the United States didn’t pledge to live “me first, me only”: in the Declaration of Independence, they said “we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.”

This university exists because the Robinsons and Amos A Lawrence shared that sense of obligation to community. Like others here today, I owe my own education to the generosity of Elizabeth M Watkins. I feel a duty to my writing gift to let my spirit soar. I feel an equal duty to the community that educated me to make that education possible for others.

A questing spirit, and a generous heart offer a cure for the narcissistic rage that threatens to consume our nation today. When we are seeking, and when we are sharing, we can overcome the furies and willful ignorance that blind all of us at times. We also become free to take risks, to jump off the high dive.

May all of you dare mighty things in the years to come. May you find strength for the next step on your journey. May you find joy along the path. Take chances. Don’t settle for the easy thing, insist on the good thing. Take nothing for granted. Share your discoveries. Above all, stop to ask the hard question: why does the bush burn, and yet is not consumed.