Kwei Quartey's Blog

November 30, 2020

WRITING AFRICAN FICTION FOR WESTERNERS

Chinua Achebe–trailblazer

Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe (1930-2013) at 70 (Photo: ABAYOMI ADESHIDA/AFP via Getty Images)

Written in 1958, Chinua Achebe‘s Things Fall Apart was one of the first African novels to receive international acclaim, and perhaps Achebe was among the first of modern African authors to teach us about writing African fiction for westerners. A complex cultural exploration of Nigeria’s Igbo people, Things Fall Apart is the story of Okonkwo, a leader in an Igbo village in Nigeria in the 1890s, who deals with his personal struggles against the backdrop of British colonialism.

Considering the depth of the Igbo tradition in the novel, it’s a wonder that western audiences embraced the work so whole-heartedly. According to R. Victoria Arana, a professor of English at Howard University, Things Fall Apart was transformational. “It had a profound re-ordering of the imaginative consciousness for people in Africa,” she said. “The book was a part of the re-storying of people who had been knocked silent.”

Writing on Achebe’s genius, philosopher and intellectual Kwame Anthony Appiah encapsulates it beautifully: ” . . . Achebe solved a problem that these earlier novels [like Palm Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola] did not. He found a way to represent for a global Anglophone audience the diction of his Igbo homeland, allowing readers of English elsewhere to experience a particular relationship to language and the world in a way that made it seem quite natural—transparent, one might almost say. Achebe enables us to hear the voices of Igboland in a new use of our own language. A measure of his achievement is that Achebe found an African voice in English that is so natural its artifice eludes us.” In the question of whether “true” African literature should belong to African language only, Achebe was quite clear that, “I feel that the English language will be able to carry the weight of my African experience. But it will have to be a new English, still in full communion with its ancestral home but altered to suit its new African surroundings.”

There is, indeed, a subtlety, complexity, and nuance in Achebe’s voice, and many African authors have tried to emulate it to varying degrees of success. It’s rather like trying to lasso a whale: it will escape every time even if it’s within your grasp. Things Fall Apart seems to have been written entirely on its own terms. I’m skeptical that such is the case for African novels nowadays, i.e. that the African voice has completely free rein to roam. I suspect that fiction from Africa is more commercially driven than it was back in the 1950s, so that the Westerner must at all costs understand the work for it to be financially successful.

The mid-20th-century renaissance

During the late colonial and early postcolonial period, African literature by the likes of Amos Tutuola, Wole Soyinka, Ayikwei Armah, and Ama Atta Aidoo sprang to life. It would be a mistake to believe that African writing began when Africans learned the language of their colonizers. The history of African literature reaches far before that, but in the 1950s to 60s, African literature tackled the conflicts between the indigenous and the invading imperial forces. Later works addressed the challenge of neocolonialism: African bureaucrats as corrupt as the ex-colonials. Both Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong’o and V.S. Naipaul tackle this in their novels, PETALS OF BLOOD and A BEND IN THE RIVER respectively, but with radically different approaches.

Present times

Now, we have another golden age of African literature, particularly with heralded works out of Nigeria. After a lull, it seems American publishers began to pay attention to new African authors who write in the diaspora for western readers. Contemporary African writers are probably more “internationalist” than the 20th-century group. In his article, Aaron Bady describes how Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie joked that, “I’m not part of a secret society of African writers that meets in some dark basement.” The international flavor of contemporary African authors can be seen in novels like Americanah, Foreign Gods, Inc, Ghana Must Go, Edible Bones, Homegoing by Adichie, Okey Ndibe, Taiye Selasi, Yaa Gyasi, and Unoma Azuah respectively. There are others too numerous to mention here, but the recognizable theme running through these examples is the transatlantic experience in the United States and West Africa in modern times and/or during the slave era. Western editors, particularly American ones, appear to have fallen in love with this narrative and have often gushed over them. This is not to imply that the books are not well written, but at least for some time, the trope appeared formulaic for success. We will see what the rest of the century brings us.

Stark truths

Most readers will be in the USA, the UK, not in Africa. It’s a tough irony that the large majority of readers in the country where the novel is set will not get to read the book.

Reading of fiction is not as widespread, or as important, in sub-Saharan Africa as it is in the West. This is changing, however. There are more and more African book clubs, some of which I’ve been a Zoom guest.

There isn’t a well-developed, wholesale book distribution system in most if not all of Africa, e.g. Baker and Taylor or Ingram. That means African bookstores ordering books at retail from the UK or US. However, one of the best bookshops in Accra, Vidya Bookstore, was able to negotiate a reduced price from the UK publishers of my novels.

Publishers need to make money, and authors need to be successful if they want to continue getting published. It would be difficult to claim that African writers in the diaspora don’t bear this in mind, even if subconsciously.

What to do?

My experience as an author writing African fiction for Westerners is that I walk a thin line writing mysteries set in Ghana. There is a push-pull aspect of it. I want to be authentic, but I want my readers to understand unfamiliar aspects of culture. My suggestions to budding “African authors” writing in the diaspora are these:

Push the envelope as you represent Africa in your stories. What your editor and your readers can tolerate may surprise you.

If you feel that a turn of phrase or a description is quintessentially related to the setting of your novel, be assertive about keeping it in the manuscript.

On the other hand, can you express it another way that retains its originality but increases understanding?

As a matter of style, I avoid throwing in indigenous words in the middle of English sentences in an attempt to flavor dialogue with the setting unless that is the way the character really talks. I believe it’s better to write sentences completely in the indigenous language and either translate them or make the context plain.

Start at the top of the ladder–you can always climb down a few rungs. Write for the setting–you can tone it down later.

The post WRITING AFRICAN FICTION FOR WESTERNERS appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

October 13, 2020

CULTURE CLASH: Writing Fiction From Diverse Life Experiences

Culture Clash: Writing Fiction From Diverse Life Experiences

In an era when the American administration is doing its best to seal the country off from foreigners and migrants including refugees, I’ve been reflecting on how exposure to people who look different from you and have different backgrounds can enrich your life. I was brought up in Ghana, which of course was a British colony. I came of age on the campus of the University of Ghana (UG), with its iconic orange-tiled roofs. Both my late Black American mother and late Ghanaian father were lecturers there, in Sociology/Social Welfare and African Studies respectively.

Balme Library, University of Ghana (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Ghana’s connections to Britain, a lot stronger then than they are now, brought a large number of nationalities to the university from all the Commonwealth of Nations. Apart from the British, there were Australians, Canadians (for some time, our next-door neighbors were Canadians), Indians, Jamaicans, Ugandans, South Africans, and others I’m sure I’ve forgotten. Without my conscious knowledge, I was likely observing and absorbing aspects of their culture. Many were a part of a memorable cast of characters, some amusing, others quite strange. I recall one lecturer who had a strange movement disorder and a habit of talking to herself. Whereas some of these professors might have a difficult time getting employment elsewhere, the academic world always has room for “unique” personalities who are sometimes both brilliant and bizarre.

Universities and colleges are often called “ivory towers,” a state of privileged seclusion or separation from the facts and practicalities of the real world. In some ways, that was the case with the University of Ghana. Quiet, clean, and rather lush, the campus was neither anything like the hectic urban life of Accra nor the rural sectors of the country, which, at the time, accounted for most of the population. That’s no longer the case, as only some 43% live in rural areas.

At the time, the University provided a perk to expatriates like my mother and dependents (if there were any): a comped visit every 2-3 years to their country of origin. That meant my three brothers and me got to accompany my mother to New York City for entire summers when classes at UG were out. That an institution in a developing country was able to provide that kind of perk seems staggering to me now–it certainly couldn’t happen now–but back then I took it for granted. Maybe I was a tad “entitled,” an uncomfortable word in the modern zeitgeist.

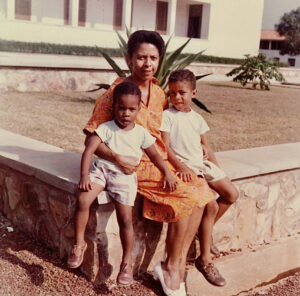

My 2nd brother (R), Mom, and me (Photo by unknown)

Because my mother was an American, her children were automatically US citizens (jus sanguinis), making travel to the US, UK, and Europe a cinch. In the face of all this, my father was uncomfortable about any show of privilege and he might have squirmed with guilt at the perk, which my pragmatic mother on the other hand made full use of. Apart from our being able to see her mother (“Granny”) in New York, my mother, as much as she loved Ghana, likely thought it important for her four boys to experience America as a part of their cultural experience and heritage. Indeed, when the time came for the family to move piecemeal to the USA (minus my father, who had died a couple of years before), American life wasn’t the culture shock that it would have been for the uninitiated.

Moving Beyond The Ivory Tower

On the diametrically opposite end of traveling to her hometown of New York City, my mother as a sociologist and social worker took her students off the university campus on field trips to remote rural areas, for which experience students of hers expressed great appreciation. Part of these visits was to explore how village life, culture, and belief systems could be used in constructive ways to advance development and mold social policy.

My mother also let us, her sons, tag along on these field trips, and there I felt the heaviness of my privileged circumstances in contrast to rural living conditions. I remember visiting one village where 80 percent of adults suffered from river blindness, or onchocerciasis. This horrific disease is caused by a parasitic worm called Onchocerca volvulus, which induces body itching so intense that one cannot sleep. Eventually, the sufferer goes blind. In villages where the affliction is endemic, it’s common to see blind adults being led around by children.

A boy leads a man blinded by onchocerciasis (Photo: WHO)

At the time of that field trip, I had already decided I wanted to be a physician, but I believe this wrenching, seminal experience solidified my ambition by raising the curtain on what truly hellish suffering is like and making me want to do something about it.

On one occasion, my mother turned down my request to accompany her to the psychiatric hospital in Accra. I remember her saying, “That’s not the kind of thing you should see.” The state of mental health care in Ghana at the time was abysmal, and that remains mostly the case now. Even with a renovation of the Accra psychiatric hospital in July 2020, an overwhelming amount of work remains to be done there, not to mention the rest of the country.

Cultural Discomfort

Bart, another of my best childhood friends, lived down the road from us on the university campus, an easy 3-minute walk between our homes. We had a lot of fun and adventure together, and I commonly stayed for lunch and went on trips with his family and vice versa. They were Dutch expatriates who had lived in Ghana for decade. Hanging out with them was a very different experience from visiting my father’s relatives a world away in “real” Accra. My mother, brothers and I were in the awkward position of not having learned my father’s indigenous language, Ga. If he had spoken it to his children from an early age while my mother spoke to us in English, we would have been fluent in both. But my father might have felt like he would be unfairly excluding her. By tradition in Ghana, my mother was largely excluded from the affairs of her husband and his side of the family. Knowing my mother had always felt cut off by this position, my father might not have wanted her to feel further isolated. At any rate, not speaking Ga fluently was (and is) a distinct disadvantage. My name Kwei is so quintessentially of the Ga people that most Ghanaians would assume I knew how to speak the language. Repeatedly trying to explain why this was not the case was (still is) a royal pain in the rear. We took formal Ga lessons when I was a teenager, but there was no immersion.

But there was, and is, more to this language deficit. Language and culture are intertwined. Interacting with another language means engaging with the culture that speaks the language. My mother was the more present and assertive parent, my father the more self-effacing. I never had a strong sense he was proud of his Ga heritage, or perhaps I never recognized it. Sure, he took my brothers and me to traditional events and family gatherings in town, but I always felt like an outsider looking in. I wasn’t standing with one foot on dry land and one in the pond, I barely had a toe in the water. And once these small nibbles of Ga culture ended, it was back to the comfortable ivory tower. These experiences were both a culture clash and a culture miss.

The Writing Paradox

While all this cross culture and diversity in my life experience are a bit of a muddle, that jumble is the very materiel and fodder for my writing. In truth, I constantly strive to grasp a culture I feel I just missed–a lost opportunity in a sense. I have a theory that a writer’s work is a surrogate for control of a world beyond control. I’m driven to wrestle with my own confusion. Each book is an exploration of Ghanaian culture and the attempt to firmly understand it, and murder mystery is the best genre in which to do it, because the central question in a murder is, why? Sure, the how is the mechanics of the matter, particularly in locked-room mysteries, but we all want to know what intricacies in the murderer’s mind compelled him to commit the crime.

In one form or the other, the backdrops to my stories have some kind of culture clash. In Wife Of The Gods, a young, progressive female medical student challenges the age-old tradition of indentured servitude of girls to a fetish priest in return for his protection against family curses. Darko Dawson is unfamiliar with this tradition, which is a culture clash within his own country. In Gold Of Our Fathers, illegal Chinese miners in Ghana are in conflict with the locals. The Missing American is where Ghanaian and American values meet like a river lagoon colliding with the sea at high tide. In a funny scene in the upcoming Sleep Well, My Lady, Emma Djan, who has little to no privilege in her background, goes undercover as a wealthy woman and discovers why people in Mercedes Benzes feel superior–because that’s what a Benz does to you. (Apologies to all Benz owners out there. Full disclosure: I don’t have one.)

I think the maxim, “Write what you know” is incomplete. I think you should also write what you care about. If there’s no emotion underlying your writing, it may seem flat. So, as long as I can write, I will keep exploring these culture clashes.

The post CULTURE CLASH: Writing Fiction From Diverse Life Experiences appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

September 3, 2020

VACCINES: HOW A MILLENNIA-OLD LIFESAVER WAS AND STILL IS CONTROVERSIAL–Part 2

Surprise: Anti-vaxxers are nothing new

Opposition to vaccination is not a 20th-21st century phenomenon. It has been prevalent for much longer than many may realize. Here’s an intriguing anti-vaccination flyer from 1807 called “The Vaccine Monster,” clearly designed to engender feelings of suspicion, disgust and fear.

The Vaccine Monster, 1807 (Image: Wiki Digital Methods)

The text that accompanied this image proclaimed that, “A mighty and horrible monster, with the horns of a bull, the hind of a horse, the jaws of a krakin, the teeth and claws of a tyger, the tail of a cow, all the evils of Pandora’s box in his belly, plague, pestilence, leprosy, purple blotches, foetid ulcers, and filthy running sores covering his body . . . has made his appearance in the world, and devores mankind —especially poor helpless infants—not by sores only, or hundreds, or thousands, but by hundreds of thousands.”

Another flyer from 1894 was accompanied by text warning of the dangers of vaccination.

(Image originally from Historical Medical Library of The College

of Physicians of Philadelphia)

Notice the reference to vaccines being poison and not only ineffective, but actually producing death. Most important is this sentence: “Any dogma of a class, medical or religious, that needs the fostering care of legislative enactment to force it upon the people, shows inherent weakness and condemns it at once among all men.” It also claims that the smallpox vaccine caused greater mortality than smallpox itself.

A Supreme Court Case

In Part 1 of this two-part series, we saw how important the smallpox vaccine became as a preventive measure against a grossly disfiguring and highly contagious disease. By 1902, smallpox vaccination was well established in Boston. Nevertheless, the disease stubbornly hung around, and officials took drastic measures. For instance, public health doctors, accompanied by guards, went to the railway yards and forcibly vaccinated “Italians, negroes and other employees.”

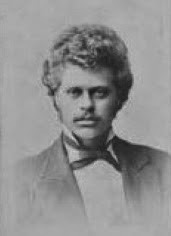

In 1902, Cambridge’s Board of Health mandated smallpox vaccination for all residents who had not been vaccinated since 1897. But a naturalized Swedish American called Reverend Henning Jacobson refused to take the vaccination, claiming that Sweden’s mandatory vaccination when he was six years old had caused him “great and extreme suffering.” He was convicted and fined $5, which he refused to pay.

Henning Jacobson (Image: New England Historical Society)

In a legal brief, Jacobson stated he rejected a law that compelled “. . . a man to offer up his body to pollution and filth and disease,” on the basis of the 14th Amendment, which states in part, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” Of note, Jacobson made dire references to vaccinations (“filth and disease”) that echoed those of the 1807 “Vaccine Monster” flyer. The Jacobson case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which held that individual liberty is not absolute and is subject to the police power of the state. Jacobson lost the case.

But in 1926, a group of health officers who went to Georgetown, DE to vaccinate the townspeople were met by an armed mob led by a retired Army Lieutenant and a city councilman. The “vaccinators” were driven out. If any of the residents of Georgetown were aware of the 1905 Supreme Court ruling, it evidently made no difference to the ire directed against the authorities.

In 1935, two separate polio vaccine trials using killed and attenuated poliovirus resulted in catastrophic morbidity and mortality in many subjects out of the 11,000 total number of people vaccinated. This doesn’t say vaccines are bad; rather it emphasizes the absolute importance of conducting careful trials before a large number of people are administered a vaccine. In 1953, Jonas Salk produced an injected vaccine for polio using a killed virus, and in fact he injected his own family members with it. In 1959, Albert Sabin brought out his oral attenuated virus, which was tried out on, strangely enough, Soviet citizens. In modern times, only the inactivated (injected) poliovirus is used in the U.S., while other countries use the oral form. Throughout the 1900s, many of the vaccines with which we’ve come to be familiar, e.g. mumps, measles, rubella, rabies, diphtheria, pertussis, meningitis, and chickenpox were developed. In 1972, the smallpox vaccine was no longer routinely administered in the U.S.

The “Case” Against Vaccines

The objections and resistance to vaccination fall into a number of categories:

Religion: It isn’t that multiple Christian denominations like Roman Catholic, Amish, Anglican, Episcopalian, have an official stance against vaccination. They do not. What we see is the individual who believes that “God is more powerful than any virus,” or some similar declaration. These people refuse vaccinations on the basis of their faith. All but two US states allow vaccination exemption on the basis of religion.

Misconceptions: Just as in foregoing centuries, some believe that vaccines actually give a person the disease or even cause death. This is still the case with the annual influenza vaccine. I have personally taken it every year for more than 20 years, but people still swear (including a surprising number of people in health care) that whenever they get the flu shot, they get the flu. It isn’t true. There may be a mild local or systemic reaction, but it is not the flu.

Concerns about adverse effects: In 1998, Andrew Wakefield published a study in the influential British medical journal, The Lancet, claiming to show that the mumps-measles-rubella (MMR) vaccine could be associated with the development of autism in twelve children. What followed was a circus of accusations and conspiracy theories that the manufacturers of the MMR vaccine were hiding the truth about its causing autism. When the cause of a disease is unknown, those affected will readily latch onto any explanation offered, no matter how flawed. Wakefield’s paper was deeply flawed, yet it took The Lancet 12 years to officially retract it. However, humans being what they are, a planted seed puts down deep roots and continues to grow unabated.

Fear of vaccine ingredients: in 1926, Alexander Glenny increased the effectiveness of the diphtheria toxoid by treating it with aluminum salts. Called an adjuvant, this increases the immune response in a subject. Much later, in 1964, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended aluminum adjuvant in the combination diptheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccine. The amount of aluminum salts contained is in fact less than the amount in normal human breast milk, but many people are under the impression that there are pieces of the metal aluminum floating around in the vaccine. Like the MMR vaccine itself, thimerasol, a preservative containing ethyl mercury, was implicated–falsely–to autism. Since 2001, thimerasol hasn’t been used in children’s vaccines, although it is still used in the adult flu vaccine unless preservative-free vaccine is specifically requested.

Immune overload: Many parents falsely believe that the multiple immunizations given to children at a single doctor visit is detrimental to a child because their immune system can’t handle them all at once.

Genocidal agent: prevalent in Africa especially is the belief that vaccines are really an attempt by western countries to kill off black Africans. Most recently, this conspiracy theory has been applied to the putatively upcoming Covid vaccine, and of interest is that Bill Gates is central to that plot. But don’t scoff at Africans just yet. Since Gates famously predicted a pandemic back in 2015, some Americans also believe that he started the pandemic himself. Others decry why he shows up on CNN talking about medical issues when he is not a physician. But guess what? President Barack Obama actually beat Gates to it (at least on YouTube) when he precisely foresaw a global airborne pandemic such as Covid back in 2014.

Individual Liberty

All those above reasons aside, a powerful theme that has run through the anti-vaxxer’s cry from way back in the 1800s until the present day is a strong objection to being told what to do by authorities. People go to a physician for a sore throat and demand antibiotics, but being asked to take a vaccine to prevent illness is a different matter. That is an imposition on one’s freedoms, as is wearing a mask to prevent spread of Covid. There are emotional, cultural, and ideological objections to vaccination. Conservative people are less likely to accept or recommend vaccination. Donald Trump has used Twitter to perpetuate the long-debunked linkage between autism and vaccines since as far back as March 2012. However, a well-known liberal, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr, also is a vaccine skeptic.

Suspicion of government and the perception that authorities are trying to take away personal freedoms are often tied to any number of dark conspiracy theories. These are sometimes triggered by signals from sharply partisan individuals with a platform, such as conservative TV and radio hosts, celebrities such as Jenny McCarthy and leaders such as President Trump, who has cast aspersions on the CDC, for example. The tangle of ideology, politics, and conspiracy theories is complex, and unfortunately it can have negative and dangerous consequences when it comes to vaccines and vaccination. Since the 19th century, we have made tremendous progress in science and technology, but for some, that “Vaccine Monster” of 1807 is still a reality.

The post VACCINES: HOW A MILLENNIA-OLD LIFESAVER WAS AND STILL IS CONTROVERSIAL–Part 2 appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

August 18, 2020

VACCINES: HOW A MILLENNIA-OLD LIFESAVER WAS, AND STILL IS, CONTROVERSIAL

In the era of Covid-19, we’ve heard a lot about vaccines and the international race to produce one. However, even if a successful vaccine emerges relatively quickly in the US, polls suggest that only 30-40% of Americans will accept the vaccine. In other words, hurry up and wait. The joint NIH-Moderna Phase 3 trial, which shows a lot of promise, has just hit a snag because they haven’t enrolled enough African Americans and Latinx subjects. Because of a long and shocking history of unethical experimentation on black people by white doctors, e.g. the Tuskegee Syphilis Study of 1932-1972, black people’s response to the suggestion of taking part in anything remotely experimental has been mostly, hell, no.

Terminology

Vaccination, inoculation and immunization are often used interchangeably, but there are distinctions:

Inoculation is the introduction of an infectious agent or toxin designed to produce an immune response without overt illness.

Vaccination is a specific type of inoculation named by Edward Jenner in reference to vaccinia, which is cowpox. Vacca is Latin for cow.

Immunization is development of immunity by any means, whether artificial or natural.

Variolation: the deliberate inoculation of an uninfected person with pustular matter containing the smallpox virus.

Famous Infection Fighters

When I was a nerdy teenager, I loved to read murder mysteries, but my other interests ranged from philosophy to science. I recall being riveted to a paperback that chronicled the history of how scientists discovered bacteria and viruses, and the luminaries who marked the milestones along a fascinating journey that included the development of vaccines. We’re talking about Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, Alexander Fleming, and so on.

My vivid imagination took me back to those bygone centuries when people ignored or misunderstood clues that science freely thrust under their noses. In May 1796, Edward Jenner, in an experiment that would have been deemed unethical in modern times, inoculated an 8-year-old boy, James Phipps, with fluid from a fresh cowpox lesion on the skin of a milkmaid. For years, Jenner had heard milkmaids say, “I shall never have smallpox for I have had cowpox. I shall never have an ugly pockmarked face.” Now Jenner wanted to see if that was true.

Edward Jenner vaccinating James Phipps, 1796 (Image: Everett Historical/Shutterstock)

Over the next 2 weeks, Phipps had mild flu-like symptoms, but when exposed to the highly infectious smallpox, Phipps was protected from contracting the disease. Jenner then did a little promotion of his vaccine, basing the word on vacca, Latin for “cow.” The 30% lethality rate and horrendous optics of smallpox drove the urgency of finding a cure or prevention. If a person survives, smallpox leaves the most appalling scarring–enough to make one suicidal.

Child with active smallpox (Photo: CDC/James Hicks)

Nothing Really New Under The Sun

However, Jenner wasn’t the first person to use the inoculation technique against smallpox. Variolation was practiced in China and India as far back as 1000 or before.

In 1648, there was a situation that will sound rather familiar to our modern ears: because of an outbreak of yellow fever in Barbados, Cuba, and the Yucatan, strict quarantine was imposed in Boston for all ships returning from the West Indies. Apparently, viruses weren’t done with Boston, because in 1657, there was a measles outbreak. In 1694, Queen Mary II died of hemorrhagic smallpox (variola hemorrhagica), a particularly vicious form of the disease.

The African Pioneer Very Few Know About

As a child in Ghana, I learned about Jenner, Pasteur, Koch et al., but no one told me nor did I read about a West African slave who brought the practice of inoculation to New England. In 1706, a prominent Puritan minister called Cotton Mather purchased an enslaved West African whom he named Onesimus (Greek for “useful”) after the Biblical slave. This appears in the Epistle of Paul to Philemon, in which Paul says, “I beseech thee for my son Onesimus, whom I have begotten in my bonds: Which in time past was to thee unprofitable, but now profitable to thee and to me . . .”

Onesimus was one of about a thousand Africans brought to Massachusetts to be servant or slave. Mather hoped Onesimus would repent of “some Actions of a thievish aspect.” Apparently the irony of Mather’s slave ownership was lost on himself. Onesimus was clearly a smart cookie, because later on, he was able to buy his way out of bondage by paying Mather to purchase another youth, Obadiah, to serve in Onesimus’s stead. Slick move, although I feel sorry for Obadiah.

Image of Onemisus, the African slave who brought inoculation to Boston (Photo: Face2FaceAfrica.com)

In 1721, yet another outbreak of smallpox ripped through Boston. At that time, Mather advocated a technique of “ye Method of Inoculation,” remarking that six years before, he had learned about it from “my Negro-Man Onesimus, who is a pretty Intelligent Fellow.” Mather had informed the Royal Society of London that Onesimus “had undergone an Operation, which had given him something of ye Small-Pox, and would forever preserve him from it, adding, That it was often used among [Africans] and whoever had ye Courage to use it, was forever free from ye Fear of the Contagion. He described ye Operation to me, and showed me in his Arm ye Scar.” Accounts of smallpox variolation appear from scattered areas of ancient Africa, including Sudan, Ethiopia, and Southern Africa.

Hearing that this technique was also practiced in Turkey, Mather mounted a public campaign in favor of inoculation, but the large majority of white doctors in town were unwilling to try something suggested by an African, except for one physician by name of Zabdiel Boylston, who was the first American doctor to perform gallstone and breast removal surgery. In that same spirit, Boylston went ahead and performed variolation on 282 Boston inhabitants, keeping records on them and 5,759 non-inoculated residents who contracted smallpox. At the time, most people considered variolation ran counter to the will of God, and both Boylston and Mather met with strong opposition and even threats of violence. If this all sounds vaguely familiar, it’s because it is. Anti-vaxxers existed in the 1700s just as they do now, and the irony is that 300 years later, the rhetoric is almost identical. Eventually, Boylston was arrested and released only on condition that he would not inoculate anyone else without government approval.

But Boylston was eventually triumphant. Of the 282 inoculated patients, only 2% died from smallpox. Of the nearly 6000 non-inoculated, 15% died. Boylston presented his findings in 1726 to the Royal Society chaired by the Royal Society.

Title page of Zabdiel Boylston’s Presentation to the Royal Society (Wikipedia Commons)

Lessons & Summary

The history of vaccination and inoculation goes back millennia. Many people do not understand that large populations have given their lives through outbreaks of smallpox and other hideous and lethal diseases in order for us to reach modern times in which lifesaving vaccination is available. Smallpox has been largely eradicated in the world as a result, and countless deaths are prevented from diseases like rabies, meningococcus, polio, diphtheria, tetanus, and yellow fever. Anti-vaxxers should carefully consider whether we really want to return to the 18th century or earlier. Recall that were it not for the development of a smallpox vaccine over the centuries by the pioneers including Onesimus, our children could still be ravaged by the horrifying and deforming affliction shown in the figure above.

The inoculation story has been largely told from the Eurocentric standpoint, but variolation, a procedure of the same principle, was practiced elsewhere, including in Africa, long before Jenner unveiled vaccination. Yet one would be hard pressed to find widely-known accounts of Onesimus’s contributions to a medical practice that has been a bedrock of public health and the eradication of disease.

For a detailed history of vaccines, I highly recommend you spend a few minutes looking at this timeline, and next post, I’ll talk about the modern age of vaccines.

The post VACCINES: HOW A MILLENNIA-OLD LIFESAVER WAS, AND STILL IS, CONTROVERSIAL appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

July 29, 2020

PRESIDENT TRUMP IS GUILTY OF NEGLIGENT MANSLAUGHTER

President Trump Is Guilty Of Negligent Manslaughter

In the era of Covid-19, physicians confront the daunting challenge of saving patients who are on the brink of death. Entrusted with the lives of others, these doctors carry a heavy burden and a sacred responsibility embedded in the Hippocratic oath.

Hippocrates, ancient Greek physician and healer, known in science as “Father of Medicine” and author of the “Hippocratic Oath.” (Shutterstock / Repina Valeriya)

The sixth paragraph of the modern version of the Oath states: “. . . Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty.” Contrary to conventional belief, nowhere does the Oath state, “First, do no harm.” Nevertheless, it makes a high commitment to caring, which is why we feel outrage over doctors who appear indifferent or even callous about the suffering of their patients.

As an example, let’s imagine a physician, Dr. X, caring for Covid-19 patients in an at-capacity ICU. A nurse alerts him that several patients are in impending respiratory failure, urgently needing intubation as their oxygen levels plummet. “I don’t agree with you,” Doctor X responds. “The patients don’t need intubation. They’re doing just fine and will soon recover on their own. If you would just stop using the oxygen meters, none of these patients would have low oxygen.” And he turns away and walks out of the unit.

Covid-19 patient on a ventilator in ICU (Photo: Shutterstock / Photocarioca)

In this scenario, Doctor X abandons his patients and fails to fulfill his sacred duty. At a minimum, he should lose his license to practice medicine, but if patients die as a result of his actions or lack thereof, he could be guilty of manslaughter by recklessness or gross negligence. Recklessness is knowingly exposing another to the risk of injury and being willing to run that risk, but in criminal negligence, there is a failure to foresee danger and thereby prevent it from occurring. It becomes “gross” when the failure entails a “wanton disregard for human life.”

President Trump did not take the Hippocratic Oath, but he did take an oath that is every bit as profound—perhaps even more so. In his inaugural address of Friday, January 20, 2017, Trump proclaimed, “. . .The oath of office I take today is an oath of allegiance to all Americans . . . We will face challenges. We will confront hardships. But we will get the job done . . . The forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer. . . This American carnage stops right here and stops right now . . . I will fight for you with every breath in my body; and I will never, ever let you down.” [My emphasis added.]

The last line is a promise not only to serve the American people, but to uncompromisingly uphold them. But what has Trump done? He has minimized the Covid-19 pandemic from the very beginning, one of his most infamous claims being that of February 26, 2020: “You have fifteen people, and the fifteen within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero.” Stunningly, almost five months later as the pandemic spins wildly out of control in the US and has killed nearly 19 times as many Americans as have died in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, he continues to say, “I think at some point that’s going to sort of just disappear, I hope.”

Like Doctor X, who dismissed the alerts of the alarmed ICU nurse and told her, “The patients don’t need intubation. They are doing just fine and will soon recover on their own,” Trump has not only ignored the warnings of epidemiologists, he has actively disagreed with expert advisors like the renowned Dr. Anthony Fauci. Trump’s asinine assertion that, “If we stop testing right now, we’d have very few cases,” is like Doctor X suggesting that all oxygen monitors be switched off to make the problem of patient hypoxia go away. Just as the doctor walked out on his unit, staff, and patients, so has President Trump abdicated all efforts to control the pandemic, which has had predictably deadly consequences, and torn people from their loved ones. Like the doctor, Trump has displayed appalling recklessness, gross negligence, and willful blindness. He has failed his oath, let the American people down, and in an open display of wanton disregard for human life, allowed thousands to die.

The post PRESIDENT TRUMP IS GUILTY OF NEGLIGENT MANSLAUGHTER appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

July 16, 2020

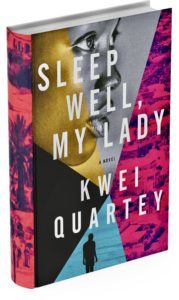

Get Ready For Sleep Well, My Lady–Coming 2021

Sleep Well, My Lady

Sleep Well, My Lady (January 2021)

In Sleep Well, My Lady, Emma Djan, Private Investigator, returns for another round on January 12, 2021. Sleep Well, My Lady (SWML). No one can predict exactly what the Covid world will be like by then, but I feel confident that in any case, we will still have books, thank goodness.

This time, Emma and the investigation team tackle a case that has run into a dead end. Almost a year ago, fashion icon Lady Araba was found dead in the bedroom of her upscale home in Trasacco Valley, which I call the Beverly Hills of Accra.

https://kweiquartey.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Trasacco-Valley.mp4

In typical fashion, the Ghana Police have arrested the most convenient scapegoat at hand, Lady Araba’s chauffeur, who is now languishing in prison waiting for a trial date that could be anything from one to ten years away. But Araba’s Aunt Dele, who taught Araba everything about designing and sewing women’s outfits, doesn’t believe the chauffeur killed his Araba. She is convinced that the guilty party is Araba’s lover, Augustus Seeza, the highest-paid TV talk show host in the country. Augustus, a notorious womanizer and alcoholic, is separated from his heiress wife and had a toxic relationship with Araba, hence the suspicion that he could be involved with her murder. Bearing this conviction, Dele comes in one morning to the Sowah Detective Agency and asks for Emma’s help in solving the crime.

It’s easier said than done when it seems like just about everyone is lying through their teeth. Emma does undercover work from pretending to be a poverty-stricken laborer to a rich woman planning to buy one of the million-dollar homes you see in the short clip. Some part of that undercover work dredges up previous trauma she must work through.

The premise of the novel is from a true story out of Kenya, which I blogged about some time ago. However the end result, SWML is different in several ways from the real-life events.

January 12, 2021 is the pub date. It’s really not that far away. Time flies, even when you’re not having fun.

The post Get Ready For Sleep Well, My Lady–Coming 2021 appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

June 13, 2020

MY TOP TEN GHANA SCENES

My Top Ten Ghana Scenes

I have thousands of photos from Ghana, many of them forming backdrops in my novels. Here are some top ten favorites in no particular order. Choose your top three!

10.

Dizzying cliffs at Cape Three Points (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Much of the Western Region coast is unspoiled, but developers have their eye on some of this prime real estate. Imagine having a home in this setting–easily a million dollars and up.

9.

Lush green cocoa forest, Ashanti Region (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Almost all chocolate in the world comes from Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana. Cocoa beans grow in red to gold cocoa pods (shown), surrounded by a delicious sweet, tangy pulp. One cocoa tree takes about 7 years to bear fruit, and they are prone to various viruses. They cannot be harvested by machine. Remember these hard-working farmers the next time you have a bar of chocolate and try to always buy Fair Trade.

7.

Canopy walkway at Kakum National Park, Central Region (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

The Kakum Canopy Walkway is 350 meters (1150 feet) long, connecting seven treetops. Because of the tremendous height and the undulation and swaying of the walk, some people panic and are unable to continue forward, and have to be “rescued” by park rangers.

6.

River view from Royal Senchi Hotel, Volta Region (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

A beautiful and tranquil location south of the Akosombo Hydroelectric Dam. I don’t know the details, but the Queen of Denmark paid a royal visit to the hotel in 2017 and dedicated a plaque to the hotel.

5.

Elephants at Mole National Park, Northern Region (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Nothing more majestic than a family of elephants close up. This herd is on the way to a local watering hole below the Zaina Lodge. The Mole Park also has several antelope varieties, wart hogs, and other animals. Reputed lions are rarely, if ever, seen.

4.

Infinity pool at Zaina Lodge, Northern Region (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Zaina Lodge offers terrific safaris, gourmet meals and beautiful vistas from the infinity pool deck, including a view of one of the favorite watering holes of elephants, which also sometimes wander onto the grounds of the Lodge. It’s a real treat to see them up so close.

3.

“Domesticated” crocodile, Paga, Northern Region (Photo: M. Zakari)

The legend of these crocodiles is that one of them rescued a Paga man being chased by a lion by allowing him to ride on its back to safety. Thereafter, the man made everyone vow never to hurt a crocodile. They are essentially domesticated with frequent meals of live chickens, paid for by intrepid travelers. Reportedly, if you find one of these crocodiles resting outside your house, it’s a blessing. A Ghanaian friend of mine declared to me, “Sacred or not, a crocodile is a crocodile and I’m never getting close to one.”

2.

A spontaneous group of children in the town of Dunkwa, Central Region (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Ghanaian children love being photographed! Dunkwa is a town featured in my novel, Gold Of Our Fathers.

1.

A troupe of drummers at the Arts Center, Accra (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

A troupe of drummers at the Arts Center, Accra (Photo: Kwei Quartey)The group gave me an impromptu, rousing performance when a friend of mine introduced me to them. The Arts Center in Accra (Ac-CRA, not “AC-cra”) is a tourist trap from which you cannot easily unentangle yourself from a horde of fast-talking vendors, but in this case, I was with a local and so was left alone (Tip: always go around with a trustworthy local.)

The post MY TOP TEN GHANA SCENES appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

April 28, 2020

COVID CRIMES

Covid Crimes

Crime in the US during the COVID-19 has followed a not altogether clear path. The general headline has been that crime rates have fallen because the stay-at-home orders has kept people from going out to commit crimes.

In Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and Oakland, the average weekly number of reported crimes in February to March dropped from about 6,150 to 3,620—a decrease of 41%. Most of the decrease was due to a fall in larceny, auto break-ins in particular. What about violent crime (homicide, rape, robbery, and assault)? Overall, it dropped from a weekly average of about 1,880 in February to about 1,360 in the last week of March—a 28% decrease.

But a subset of violent crime that must be carved out for attention is domestic violence. Worldwide, domestic abuse hotlines are lighting up as staying at home fuels brutality. In the U.S, since March 16, 2020, the National Domestic Violence Hotline has received 2,345 calls in which COVID-19 was a tool of abuse.

Covid Crimes: Domestic abuse (Shutterstock/sdecoret)

The scenarios related in these calls illustrate just how manipulative these wretched abusers are; e.g. abusers preventing healthcare workers from going to work, because the victim is “purposely trying to infect them with COVID-19 by going to work.” For the abused, shelter-in-place restrictions can result in anything but safety because typical resources for victims may be less accessible: refuges may be closing or limiting their intake; in addition, there is little someone can do to physically escape their abuser.

People in close quarters in a home where tempers can flare may act as a powder keg. On April 27, 2020, a Milwaukee man shot five family members dead at home and made the 911 call himself. Officials stated that the shooting was “very much a family matter.”

Covid Crimes: The Bizarre Stuff

Trust human beings to come up with the strangest things.

Wyndham Lathem is the former professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine who was charged in the 2017 murder of his boyfriend. World-renowned in infectious disease, Lathem has asked a judge to free him from Cook County Jail on $1 million bail, because, Lathem says, his research skills could help save lives. Yeah, sure. Petition denied.

Missouri cops arrested a man accused of filming himself licking deodorant in a Walmart. You can watch the video here.

A Wisconsin woman “protested” coronavirus by licking the door handles of a grocery store freezer, police say.

In Colorado, police say a woman who crashed into four cars spit on a cop and told him, “There’s some Corona for you, now all you need is a lime,” The Denver Post reported.

COVID Crimes: Corona and lime (Shutterstock/AlenKadr)

The post COVID CRIMES appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

WHY YOU SHOULD CONSIDER GETTING A DNI COVID-19 BRACELET

WHY YOU SHOULD CONSIDER GETTING A DNI BRACELET

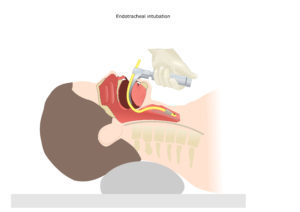

As countries clamor for ventilators, these complex machines have been assigned a kind of messianic status, but they also have a dark side. For a patient with COVID-19 (the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-19), placement on a ventilator is itself a dismal prognosticator. By that time, the patient is gravely ill and the prospects of coming off the ventilator are grim. For example, researchers in Wuhan have reported that out of 37 critically ill COVID-19 patients who were placed on mechanical ventilators, 30 (81%) had died within a month. New York state and city officials have documented a similar percentage.

Although ventilators are potential life savers, they are also agents of spread of the novel coronavirus. This is because during the procedure of intubation, a COVID-19 patient’s secretions are invariably aerosolized, directly exposing the physician to a high risk of contracting the virus. In Italy, many of the more than one hundred physician deaths due to COVID-19 have been linked to inadequate PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) during intubation, the very procedure designed to save a life. Without comprehensive PPE similar to the all-encompassing protective garb of the Ebola era, many of the world’s doctors have become sitting ducks for SARS-CoV-19 infection. Even if PPE is adequate during the procedure, removing (“doffing”) the shield, mask, robe and in some cases the PAPRs (powered air purifying respirators) can be a risky process as well.

Full PPE (Som Taste/Shutterstock)

Decades ago, I was an aggressive young intern at the USC Medical Center. There was no procedure I wouldn’t attempt to save a life. As I intubated a man in respiratory failure one night, a rich gob of sputum came up his windpipe and splattered me. What I couldn’t see, though, were the millions of “nanoparticles” that were undoubtedly released from this patient, who turned out to have tuberculosis. A similar phenomenon applies to the novel coronavirus. Not only does it threaten the life of the physician performing an intubation, the lingering virus-laden air droplets may indirectly expose innocent bystanders.

Intubation (ChaNaWiT/Shutterstock)

Physicians have a deep-seated urge to intubate patients in respiratory distress. The procedure has been logically extended to COVID-19 sufferers with pneumonia or the dreaded acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)—a condition in which severe inflammation engulfs the lungs and impairs gaseous exchange. But are we correctly weighing the benefits versus the risks? Some doctors, and rightly so in my opinion, are moving away from ventilators as a treatment for COVID-19 because of the extraordinarily high mortality rate of coronavirus patients on ventilators. The reasons, at least in part, may be that much higher ventilator pressure settings are required in COVID-19 ARDS cases and may thereby cause pulmonary barotrauma, especially since these patients may be on a ventilator for prolonged periods before either death or survival.

How to intubate (Shutterstock/ellepigrafica)

The bottom line is, if I’m ever unfortunate enough to be rushed to an emergency room in COVID-19 respiratory failure, look for the bracelet on my left wrist that reads, Do Not Intubate (DNI). “Do not resuscitate (DNR)” is too vague and broad a term, and it might be misinterpreted as a rejection of simpler procedures like high-flow oxygen and antiarrythmic medications, which I would consider absolutely reasonable. So, my dear fellow physician: try everything you have in your medical armamentarium, but whatever you do, do not intubate me.

____________________________________________________________________________

The post WHY YOU SHOULD CONSIDER GETTING A DNI COVID-19 BRACELET appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

April 14, 2020

A NEW TWIST TO MEDICINE AND WRITING IN THE COVID-19 ERA

Medicine and Writing in the COVID-19 era

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned life upside down in so many ways it’s difficult to quantify. For me, it has touched on my writer-doctor career in special ways. As you probably know, many well-known writers have also been physicians, e.g. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Anton Chekhov, Robin Cook, and so on.

Medicine

Although I’m not “on the frontlines” anymore, having retired from medicine in 2018 to write novels full time, I have a particular sensitivity to the havoc wreaked upon the hospitals all over the world by COVID-19. ERs and ICUs shown on TV full to capacity remind me of my on-call days and nights at USC-LA County Medical Center when it seemed like there was no end to the relentless flow of patients. At the ungodly hour of 3 AM, exhaustion was so profound that sometimes I couldn’t feel my feet as I went back and forth between the wards and ERs.

L.A. County USC Medical Center, the newer one on the right, the older on the left (David Tonelson/Shutterstock)

COVID-19 has suddenly familiarized the lay public with words and phrases like N-95 masks/respirators, (removes 95% of all particles that are at least 0.3 micrometers in diameter, Not oil resistant); ventilators, or “vents” as doctors often refer to them; and intubation, the procedure of placing a tube into the windpipe in order to attach the patient to the vent; and perhaps above all, PPE, Personal Protective Equipment, vital to keep doctors and nurses safe.

Full PPE (Som Taste/Shutterstock)

As a physician, there will always be a tendency to feel like going back to the battlefield, and the call is so urgent that California Governor Gavin Newsome has waived fees for retired physicians to reactivate their licenses (a stiff $808). It’s unlikely I’ll return to brick-and-mortar clinics, wards or emergency rooms, but there’s an appealing alternative. One result of the COVID-19 pandemic is a quickly burgeoning interest in telemedicine, i.e., the remote diagnosis and treatment of patients by means of telecommunications technology.

Long before COVID-19, I’ve been interested in telemedicine not only because I think not all in-person visits to one’s physician are completely necessary, but also because of telemedicine’s potential as a tool in developing countries, where the doctor-to-population ratio is very low and going to see a doctor could mean a day-long trip from the village to the nearest clinic/hospital. One of my specialties, chronic (non-healing) wound care, is particularly suited to telemedicine. If a nurse goes out to a remote area, he or she can transmit an image of the wound back to the office and the physician, who can recommend on-the-spot treatment from the nurse’s well-supplied wound kit. But up until now, physician reimbursement has depended on seeing a patient in person in the doctor’s office. In a large, traffic-choked city like Los Angeles, a medically stable patient may commute 2 hours to his/her doctor’s office just for a routine visit lasting 10-15 minutes. Maybe COVID-19 can show us that a telemedical visit could have achieved the same thing effectively and efficiently.

Writing

I will wager that at this moment, writers are incorporating the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic in their novels, or are writing medical thrillers based on COVID-19–not that it hasn’t been done before. I consider Robin Cook (Contagion) a master of pandemic fiction, as is Michael Crichton (The Andromeda Strain). What’s remarkable is that the scenarios in these fictional accounts are no longer unlikely or the stuff of mere fantasy. This doesn’t necessarily make pandemic fiction any easier to write.

Although I will probably not write a medical thriller–it’s funny, you’d think I could or should!–but the next Darko Dawson novel I’m working on will have COVID-19 as a backdrop.

A few scenarios have occurred to me in which the disease can add some interesting scenarios to mysteries and thrillers:

How did the crime occur when everyone was on lockdown–the “impossible” crime?

How does a detective investigate a murder when everyone is on lockdown? Is s/he morally obligated to investigate while the pandemic is swirling? What about the investigator’s family who might become infected secondarily?

The victim had asymptomatic COVID-19; the prime suspect denies ever having been in contact with the victim, but then the suspect comes down with COVID-19 five days later. That might strengthen the case against him or her.

The victim didn’t have COVID-19. If traces of COVID-19 RNA are detected at the crime scene, who left it there, and can s/he be traced?

The RNA of the virus can be sequenced. If the COVID-19 RNA of the victim and a possible suspect are identical, what does that add to the case?

For an international thriller, what if an assassin (think The Day Of The Jackal ) denies being in a particular country–let’s say, Iceland–but his COVID-19 genome is typical of the Icelandic pattern? That’s complicated, but thriller readers love a challenge!

There’s any number of setups using the COVID-19 pandemic as an environment in which a mystery or thriller takes place, but its appearance in some shape or form is pretty much inevitable. In medicine and writing, it’s the elephant in the room that can’t be ignored.

The post A NEW TWIST TO MEDICINE AND WRITING IN THE COVID-19 ERA appeared first on Kwei Quartey.