Kwei Quartey's Blog, page 4

February 4, 2018

How Old Is African Literature?

The post How Old Is African Literature? appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

November 1, 2017

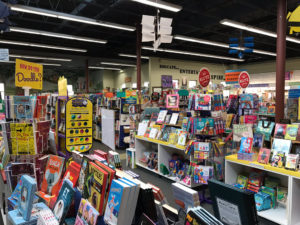

VROMAN’S BOOKSTORE–PASADENA LANDMARK

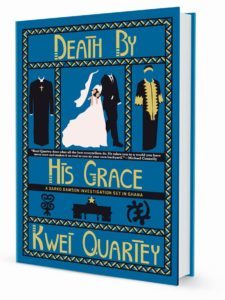

From time to time, I blog about an independent bookstore of note, e.g. Marcus Books. A couple of weeks ago on October 14, I had a book signing at Vroman’s Bookstore in my hometown of Pasadena, California for the launch of Death By His Grace, Inspector Dawson novel #5. As Vroman’s approaches its 123rd birthday, it’s fitting to talk about its historical and cultural importance in Southern California generally and Pasadena in particular.

Vroman’s Bookstore rear entrance (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Vroman’s Bookstore rear courtyard (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Launching Death By His Grace at Vroman’s Bookstore Oct 14, 2017 (Photo: Mike Pashtorian)

A brief history of Vroman’s Bookstore

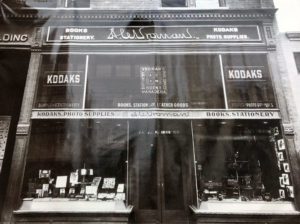

The oldest and largest independent bookstore in Southern California, Vroman’s is named after Adam Clark Vroman, who founded the store in 1894. The original Vroman’s Book and Photographic Supply store was located at 60 E. Colorado St in Pasadena, California. Now it’s at 695 E. Colorado Blvd.

Wall banner of Vroman’s Bookstore c. 1910 (Photo of banner: Kwei Quartey)

Mr. Vroman loved books and valued giving back to his community, which remains a core principle of the bookstore till t0day.

Arthur C. Vroman, consummate gentleman and founder of Vroman’s Bookstore, in his office around 1900 (Photo from Historic Pasadena: An Illustrated History, by Ann Scheid, Ann Scheid Lund)

He was born in 1856 in La Salle Illinois. When he moved to Pasadena in 1892, he was hoping that a change in climate would help preserve the health of his infirm wife, Esther. Regrettably, that wasn’t to be the case, and she died two years later. Vroman wanted to remain in Pasadena and he opened the city’s first bookstore on November 15, 1894 in partnership with stationer J.S. Glassock. At the time, one hotel, a blacksmith shop and a butcher comprised the business district. Mr. Vroman was also a passionate photographer, specializing in scenes of the American West and his portraits of the Hopi Indians and other cultures of the American Southwest. When Mr. Vroman died in 1916, he had built a solid business with loyal employees in whom he had shown deep interest. His friend and associate George F. Howell, became president of the newly incorporated bookstore when Vroman died. Allan David Sheldon, Vroman’s godson, succeeded Howell in 1920. The Sheldons continued to own and run Vroman’s and the bookstore’s present chairman is Joel Sheldon.

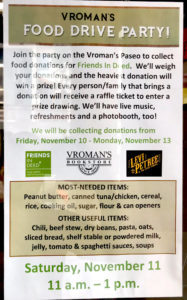

Mr. Vroman’s legacy of philanthropy has continued. The store has supported causes through food drives, holiday gift drives, free HIV testing, bone marrow donor match drives, pet adoption days, and the Vroman’s Gives Back program. Vroman’s Gives Back is a charity program that donates a portion of customers’ purchases to local nonprofits, including public radio stations, arts centers, family services, and programs supporting literacy.

Vroman’s Bookstore food drive (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Vroman’s Bookstore author events

Like other bookstores, Vroman’s holds book discussions and signings, but most bookstores don’t have the luxury of space that Vroman’s has on its second floor for author events.

Vroman’s Bookstore event space (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Packed Children’s Institute attendees attending a panel at Vroman’s Bookstore in 2015 (Photo: American Booksellers Association)

I’ve signed with Vroman’s for every novel in the Inspector Darko Dawson series, starting with Wife Of The Gods up till the present Death By His Grace.

Reading at Vroman’s Bookstore Oct 14, 2017

Every week the Vroman’s bestsellers are displayed. During the week after an author’s book signing, it’s common for his or her book to hold a high placing on the list, even if short-lived.

Vroman’s Bookstore bestsellers (photo: Kwei Quartey)

The other bestseller display in the store derives from the Los Angeles Times bestseller list.

Los Angeles Times Bestsellers at Vroman’s Bookstore (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Vroman’s treats its local authors very well, but national and international powerhouse writers have flocked to the bookstore too, including Louise Penny (Canada), Jo Nesbø [pronounced “You Nes-buh”](Norway), President Bill Clinton, President Jimmy Carter, Irving Stone, Upton Sinclair, Ray Bradbury, David Sedaris, Salman Rushdie, Walter Mosely, Joan Didion, Barbara Walters, Anne Rice, Neil Gaiman, and Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

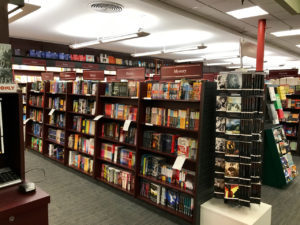

Happily for me, a mystery writer, the Mystery section of the store is one of the largest.

Mystery section at Vroman’s Bookstore (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Diversification

I’m no financial wizard, but adding diverse merchandise besides books to a bookstore is a smart move, particularly during times in which the paper book is “under attack,” such as when the Kindle e-reader arrived in 2007 and doomsayers predicted the imminent death of the paper book. Clearly, the prediction has proved wrong, thank goodness, but it doesn’t hurt to stock “supportive” merchandise.

Vroman’s Bookstore Pens & Stationary (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Part-time Vroman’s Bookstore employee and actor/producer Michael “Dean” Porter in the gift shop (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Vroman’s Bookstore and children

Vroman’s has recognized the importance of investing in children, and it has a large kids’ section.

Kids section at Vroman’s Bookstore (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Every Wednesday and Saturday at 10 AM, the bookstore’s own Mr. Steve holds a children’s storytime. The smaller Hastings Ranch store also has a kids’ storytime on Tuesday mornings.

Vroman’s Bookstore Mr. Steve reading to kids on a Wednesday morning (Photo: Kwei Quartey)

Getting children into reading early is a way to ensure that generations to come will continue to read, which means Vroman’s Bookstore will continue for another 120 years, and 120 after that, which is good news for authors and readers alike.

The post VROMAN’S BOOKSTORE–PASADENA LANDMARK appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

September 10, 2017

THE GOODREADS GIVEAWAY

Goodreads giveaway

Goodreads is one of the bookiest online places to be. It’s got avid readers, book lovers, and tons of reviews. With over 300 million pageviews and 45 million unique visitors a month, GR also very influential and I recommend you join if you haven’t already.

Ten lucky Goodreaders won my first giveaway of Death By His Grace in the first week of its release and the books went out yesterday (September 9.)

The Goodreads giveaway, hardcover hot off the press

All the winners were in the US, anywhere from southern California to Idaho–and not just big cities/towns, either. One address is rural, according to the post office guys–and they should know.

I actually love giveaways. My books are my connection to my readers, so sending a personal copy of my novels is an added touch. There are studies suggesting that giving provides more “happiness” than receiving, and I certainly enjoy sending the books out.

Anyway, good news–another Goodreads giveaway hits from September 16 to 23! So hook up with Goodreads for that, and good luck!

Elsewhere on my website, you’ll find a listing of the book events for Death By His Grace, and I’ll send out a newsletter before each one takes place. Speaking of giving, I will have some amazing swag at the signings too: tote bags, pens, mouse pads, T-shirts and coffee mugs

Unlike Goodreads giveaways–you have to come to my book signings for these! Yes, shameless seduction. And if you prefer just to join other readers for a nice time and a reading from Death By His Grace, that will be just fine as well. Either way, it will be great to see my readers again. Take note in particular to the readings at Eso Won (Oct 11) and Vroman’s (Oct 14). Those should be particularly good!

The post THE GOODREADS GIVEAWAY appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

August 30, 2017

CLIFFHANGER: DEATH BY HIS GRACE

Hey, what’s up with the cliffhanger?

Even before this week when the latest Darko Dawson novel, DEATH BY HIS GRACE, was released in hardcover, a bit of a controversy developed among reviewers who received the advance copies. It concerned the cliffhanger ending, which some found upsetting. Library Journal predicted in their review: that “Series fans may be stunned by the suddenness of the unexpected cliffhanger ending.” They were right! One of my readers told me I was “so wrong” to end it the way I did, to which my editor at Soho Press tersely commented, “[Kwei,] you have a right to end a book however you want.”

DEATH BY HIS GRACE: Cliffhanger!

Some readers like a conventional and neatly tied-up ending to a book, but such endings have begun to appeal to me less and less for a couple reasons. The first is that life is messy and rarely wraps up nicely. I know that novels are fantasy or “escape,” but my novels are based in reality and the realities tackled can be rather heavy and dark. Murder, my subject matter, is dark and horrifying–unless it’s a Miss Marple cozy in which the village vicar was killed politely in the vestry. There’s never any blood there. There’s plenty in mine.

In a cliffhanger, DSI Gibson (Gillian Anderson) leans over Paul Spector (Jamie Dornan) as he lies dying–or is he?

Second, I’m rather shifting to what I call “the Netflix model.” My stories in the future are going to be “Netflix ready,” in other words, adaptible to one or more seasons of three or more episodes. The Netflixers among us know how many great suspense and mystery thrillers on the small screen have ended in cliffhangers. One of my personal best examples is The Fall, with Gillian Anderson and the mesmerizing Jamie Dornan. The end of Series [Season] 2 left me with my mouth open and my eyes big as saucers. But I loved it!

At the moment there’s a raging debate about the finale climax of Season 7 of Game Of Thrones. Clearly, my novels are not epic fantasies, but I think you get my point that in series, cliffhangers are often par for the course. As I shift my writing slightly to being screen-ready, readers should know that there may be more cliffhangers in store. In fact, my next novel, tentatively titled Dead American, will almost certainly end in a cliffhanger.

For more comments and reviews on DEATH BY HIS GRACE, see here, and please read the novel for yourself and add your two cents on Goodreads and/or Amazon.com.

The post CLIFFHANGER: DEATH BY HIS GRACE appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

August 12, 2017

DOCTORS IN TRAINING: Top-down experience

Doctors In Training: The Pecking Order

After the first two medical school years of only classroom and lab work, a medical student begins his/her clinical rotations in the hospital. There’s both excitement and anticipation as you find out which specialty you’ll begin with. My first clinical rotation, Obstetrics-Gynecology, was at Howard University Hospital (HUH) in Washington, D.C.

Howard University Hospital

Students were paired up and remained partnered until the end of the rotation. If you didn’t like your colleague, you were stuck. Before we paired off, however, we all observed a live delivery. One of the tallest, strongest, jockiest guys, who had played football in college, immediately fainted while witnessing the birth. That was my first lesson that it’s the most macho guys who invariably faint at the sight of a little blood or procedure–reliably true to this day.

The hierarchy for doctors in training is clear from the beginning. The medical student is at the bottom. He or she may be used for anything from running blood, sputum, spinal fluid (and worse) to wheeling a patient down to the x-ray department or going on a pizza run. Pizza tastes especially good at 3 AM while you’re on duty. Next after the med student is the intern, who does a lot of scut work as well, but is often responsible for the bulk of the medical histories and exams of the patients admitted to the team. There may be one, two or three interns on the team. The 2nd-year resident has completed his/her internship and has confidence to supervise the interns. The 3rd-year resident is of course more experienced than the whole bunch, and a lot of the time can get a little cocky, having survived two years of baptism by fire. The 3rd-year supervises everyone and must be ready to defend his or her juniors during rounds. He or she is often cruising through the lighter specialties for the final year, having a relatively relaxing time and actually getting home at a decent hour. In longer residencies like General Surgery, which can be 5 years, there will also be 4th- and 5th-year residents. The chief resident, as you can guess by the name, is the boss of all the residents and is supposed to liase with them and the directors of the residency program. He or she usually has exceptional smarts and clinical skills. I remember when I was a medical student, I thought the chief residents walked on water. Above all of the residents are the faculty and attending physicians and the head of the department.

After completing med school at HUH, I moved to southern California to start an internship in Internal Medicine at Martin Luther King Hospital in the Willowbrook area of south LA.

Present modern facade of MLK Hospital, ideal for doctors in training (Photo:hmcarchitects.com)

Doctors in training must endure rounds . . . and more rounds

There are all kinds of “rounds” for doctors in training. You’ll round till you’re sick to death of rounds. They are any form of meeting between medical professionals to discuss cases. After every admission night, there are usually intake rounds (sometimes called morning conference/report) wherein new and/or complicated admissions are discussed with the chief of staff or program director, senior physicians, chief and senior residents.

Morning report: staff and doctors in training in the Pediatrics Dept at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (Photo: Vanderbilt University)

Thereafter the teams split up for their respective attending rounds headed by an assigned attending physician, who will listen to the accounts of the new cases, examine the patients, do some teaching for the benefit of the doctors in training and medical students, and make suggestions for diagnostic workups and treatment.

The team may be small, depending on the size of the residency program and the specialty as shown here:

Bedside rounds: smaller team with attending physician demonstrating a physical sign to the doctors in training and medical student (Photo: Abbott Northwestern Hospital)

The team may be larger and include nurses, allied healthcare professionals such as respiratory therapists, nutritionists, and social workers.

Hospital rounds at Duke University Hospital with a larger team of the attending (Dr. Carmelo Graffagnino, right,) and doctors in training (Photo: Duke University)

The medical students (circled) are recognizable either by their short white jackets or simply looking younger than everyone else.

The art of the medical history & physical exam (“H&P”)

The intern and/or the 2nd-year resident, sometimes the 3rd-year as well, “present” the cases to the attending physician. In general, the narrative should follow a stylized pattern that all doctors in training must master.

Chief complaint: the problem that made the patient seek attention or to be brought to medical care, e.g. chest pain, cough, headache, weakness, dizziness, etc.

The present history: the story of the illness related to the chief complaint, including signs and symptoms, starting with the words: “This is a 70-year-old man/woman/male/female who came in for . . . “

Previous medical history and past illness, if any.

Previous surgical history, if any.

Relevant family history, if any.

Medications taken, including prescribed and over-the-counter.

Allergies to anything, if any.

Physical exam with vital signs, i.e. blood pressure, temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate; some authorities recommend adding the pain level (the patient’s, not yours); pertinent positive findings (what the patient has, e.g. an abnormal heart rhythm); and pertinent negatives (what the patient does not have, e.g. swelling of the lymph nodes)

Laboratory findings so far–some may not be ready until several hours, days, or even weeks.

Obviously, such a case presentation can take quite a bit of time. The skill is to present it clearly and concisely and not put everyone to sleep by droning on about unimportant issues. Medical students and interns fresh on the wards tend to give long drawn out presentations while the more seasoned residents squirm inwardly and pray for a more speedy narrative. After the presentation, the attending may have a few questions before going with the team into the patient’s room to talk to him or her, examine him or her, and possibly teach all the doctors in training techniques or significant physical signs present. Now imagine going through the same process with anything from five to fifteen new patients and you could be rounding for hours. Many attendings are very helpful in speeding up the process and often at the end of rounds you feel you’ve learned a lot in a short time.

Dealing with a heavy patient load

Depending on the number of patients a team admits to its service on sequential admission days or nights and how many preexisting patients have been discharged or otherwise sent elsewhere, the number of patients carried by the team can become overwhelming. The third-year resident, if he or she is on top of it, will help the residents and interns thin out the patient census on the service as quickly as possible and by whatever means available.

In my residency, one technique of cutting down the patient load was turfing, i.e., getting a patient transferred to someone else’s turf (specialty, floor, or ward) or even another hospital. For example, if you admitted a patient with kidney failure, you would want to turf him or her to the renal ward, or someone with a life-threatening illness may need to go to the ICU. I had a 3rd-year resident who always said, “Don’t talk to me about interesting medical cases. An interesting case is one we can turf to the VA [Veterans’ Administration] Hospital.” We did admit quite a few veterans.

Mind you, turfing is often in the best interest of the patient as well and isn’t necessarily a selfish act by the team. Nevertheless, there are often “turf wars,” in which the tentative receiving service may be resistant to accepting a patient from the transferring service. At times, there are furious arguments as to whether the transfer has merit. Politically well-connected and/or popular residents often win the turf wars. For example, if the chief resident says a patient must be moved elsewhere, it’s going to happen tout de suite. It’s in anyone’s interest to cozy up to the chief resident. Unfortunately I didn’t cozy up to anyone during my residency.

The problem with ward rounds and teaching rounds the morning after a long night of new patient admissions to the service is there is a lot of work waiting to be done while rounds are proceeding–workups, diagnoses, and treatment. If ward rounds go into lunchtime, it leaves only the afternoon to do a bunch of stuff before you get to go home for some sleep. When I was a medical student on the General Surgery service, the residents complained bitterly about all the time the attendings spent quizzing and teaching the students on morning rounds.

Pimp sessions

I did my internship at MLK Hospital (see above) where rounds were quite lowkey. But when I moved to the ginormous Los Angeles County University of Southern California General Hospital (or LAC-USC Medical Center), at the time the largest teaching hospital in the US, it was a different story.

The old LAC-USC General Hospital: iconic building and second home to thousands of doctors in training and the image used on the long running soap General Hospital (Photo: physiciansnewsnetwork.com)

Still home to thousands of doctors in training, the newer LAC-USC, foreground, older building in background (Photo by Downtowngal)

Attending rounds earned some unpleasant apellations, e.g. such as “pimping” or “firing squad.” Actually I was never sure “pimping” is the right characterization, but it probably referred to the bullying and humilation that could occur on rounds. It could be that there’s a kinder, gentler approach now (it’s been quite a while since I’ve been on medical rounds in a teaching hospital, so I may need some updating on what it’s like at present) but historically attending/ward rounds could be quite stressful if the attending physician(s) and sometimes the senior/chief resident(s) pounced on an intern or second-year resident with very difficult questions either about the disease process of a patient, obscure medical syndromes, or any aspect of the H&P that was lacking. I found the environment at LAC-USC was very much about one-upmanship, flashy displays of knowledge, and putting others down. It’s perhaps unsurprising in a place with very brainy, competitive people. That in itself isn’t bad. What’s bad is the appearance of deliberately trying to dominate or embarrass medical students and doctors in training by stumping them in front of a team of several people, and then chastising them for not displaying encyclopedic knowledge. Nevertheless, I have to say that the tough lessons learned from being humiliated became seared in my memory and served me well when I got into practice. So was “pimping” a good thing? I think it’s the way you take it as an individual. The more you can shrug it off, the better. I didn’t shrug off my humilations too well.

The mother of them all: Grand Rounds

Grand Rounds are pretty much what their description is: grand. It’s a big deal with a large meeting of several disciplines. Often a challenging and baffling medical case is presented and a guest speaker or panel of brainy specialists will discuss it back and forth. They’re pretty enjoyable and can be funny at times. Serious doctors often have a surprising and wry sense of humor, particularly the ones who have been around for quite a while. Sometimes you shake your head in amazement at how brilliant the expert or guest physicians can be. At some Grand Rounds, they give their best guess before the final diagnosis (if available) is revealed to them.

Grand rounds at Jackson Memorial Hospital with the big shots (left), physician staff, doctors in training, ancillary staff, medical students, etc. (Photo: @Surgeon_General 2016)

There’s a lot of learning packed into the 3+ years of residency. In my next blog, I’ll talk about what it’s really like on a night-on-duty from hell.

The post DOCTORS IN TRAINING: Top-down experience appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

July 29, 2017

AFRICAN WRITERS–Critics and Critiques

What have critics said about African writers?

In his paper Themes in African Literature Today, Per Wastberg states: “African Literature does not create masterpieces in the fastidious Western sense of the word. The interest lies in what the works deal with and not so much in what they constitute as poetry or form.” Could this be the smug, Eurocentric perspective I discussed in my previous blog? Wendy Belcher, Princeton professor of medieval, early modern, and modern African literature, thinks Wastberg’s statement is ludicrous (personal communication) and states that in fact she has a class titled, “Masterpieces of African Literature.” One might accuse Wastberg of being racist with his statement, but the author was active in the anti-apartheid movement and ironically a friend of South African writer and political activist Nadine Gordimer. Could that be why Wastberg excluded South African writers in his analysis of African literature?

Gordimer with Mandela in Johannesburgh, 2005 (Credit: Radu Sigheti/Reuters)

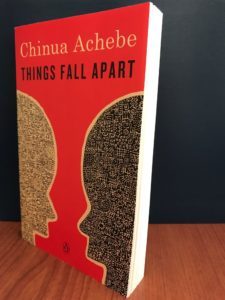

Nadine Gordimer’s writing arose in the Apartheid era. Social and political injustice stimulates great fiction. Particularly for sub-Saharan Africa and Africans, the colonial and postcolonial eras were key in shaping the themes African writers have tackled. The 1950s

Things Fall Apart: an icon among African writers (Photo of Penguin edition by Kwei Quartey)

were a kind of golden age for African writers, particularly with Chinua Achebe’s famous Things Fall Apart (TFA). That work has been analyzed, critiqued, evaluated and examined in so much depth, I doubt I can add to it, but most critics appear to agree the TFA tale of Nigerian villager Okonkwo is a strong statement about the destructive consequences of colonialism on African culture and society. But Achebe also became a forceful critic of post-colonial Nigerian governments as well. After a car crash in Nigeria in 1990, he left Nigeria for the United States, where he died in 2013 after a career of teaching at Bard College and Brown University. The success of TFA was, and still is, profound. Translated into myriad languages and selling more than 12 million copies worldwide, the work is required reading in many colleges and secondary schools around the globe. It is held up as a classic in African literature and literature as a whole. To this day, African writers name it as an inspiration and a standard to which to aspire.

Themes tackled by African writers

Ali Mazrui listed seven themes in African writers wrestle with: the clash between

Africa’s past and present;

Tradition and modernity;

Indigenous and foreign;

Individualism and community;

Socialism and capitalism;

Development and self-reliance;

Africanity and humanity.

If Mazrui is right, then Things Fall Apart embodied one or more of the themes. But I’m not

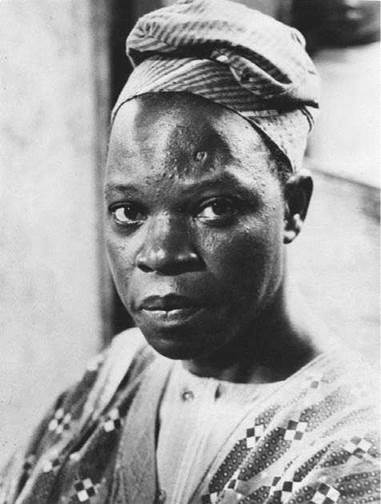

Amos Tutuola, an unique voice among African writers (Photo: schoolbag.info)

certain that Amos Tutuola‘s The Palm-Wine Drinkard (PWD), which beat TFA to publication by six years (1952 and 1958, respectively), does. The novel is about an unnamed man (the narrator) who is addicted to palm wine. When his tapster (one who taps the palm tree for the sap used to prepare the wine) dies, the desperate narrator sets off for Dead’s Town to try to get the tapster back. He travels through a world of magic and supernatural beings and goes through multiple tests before gaining a magic egg with never-ending palm wine. Published by Faber and Faber, the story is told in pidgin English, which became some of the focus of much of the West’s criticism.

Although Dylan Thomas described Tutuola’s work as “young English” and praised the book in a marvelous review, others were not as sanguine. The New York Times Book Review described Tutuola as “a true primitive” whose world had “no connection at all with the European rational and Christian traditions,” adding that Tutuola was “not a revolutionist of the word, …not a surrealist” but an author with an “un-willed style” whose text had “nothing to do with the author’s intentions. Rational and Christian traditions? Seriously? Other adjectives used to describe Tutuola’s style included, “lazy,” and “barbaric.” This kind of contemptuous commentary is a good example of Eurocentric smugness about their literature, to which I referred in my previous blog.

Other notable African writers include Ghanaians Ama Ata Aidoo and Abena Busia, Nigerian Wole Soyinka, who won the 1986 Prize in Literature (the first African to have done so), Senegalese Sembene Ousmane, Cameroonian Ferdinand Oyono, Kenyan Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Nigerian Cyprian Ekwensi, Guinean Camara Laye (whom Adele King and others believe did not solely pen either of his novels L’Enfant Noir [The African Child] and Le Regard du Roi, particularly the latter) and Ghanaian Ayi Kwei Armah, who wrote the memoir The Eloquence Of The Scribes, an exploration of the connections between the oral and written traditions of ancient Egypt, feudal Africa and contemporary Africa, some of which I touched on in the previous blog.

Young Camara Laye (Photo docsafro.com)

Breadth of African writing

In taking a critical look at the work of African writers, we need to be careful not to think of their themes and subject matter as monolithic. Lucianne Englert points out in an article that in fact there’s a vast array of types of literature from African writers. And Michael Chapman of the University of Natal, Durban, suggests we use the plural form, literatures. He states, “African Literatures remind us that Africa is far from homogeneous in language, culture, religion, style, or in the processes of its modernity. Rather, it is what Ali A. Mazrui describes as something of a ‘bazaar.'”

A second pitfall is to entertain the impression that the works of African writers has somehow stopped. No, Chinua Achebe isn’t all there was or is. There is a rich collection of worthy contemporary African writers, including my fellow Soho Press author, Okey Ndibe.

I recommend taking a look at Publishers Weekly’s 10 Essential African Novels, in which five modern African authors choose their two favorite African novels. It’s a great list that includes some of Mazrui’s seven themes and even others, perhaps.

African writers who draw attention to themselves have to a large part penned literary fiction, but I personally think a lot about another genre I’d like to see from African writers, and that’s mystery fiction and detective stories. Purists may argue that by definition, African literature cannot possibly include mystery fiction. Nevertheless, in an upcoming blog, I would like to consider the present state of mystery fiction by African writers.

The post AFRICAN WRITERS–Critics and Critiques appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

July 15, 2017

AFRICAN LITERATURE–Why it deserves better

African Literature: What is it?

African literature has been much written about. There is still debate about what it really is, its themes and its style and content. A notable aspect is that it includes both the oral and written literatures. The etymologic definition of literature is “writing formed with letters,” from the Latin littera (letters). Therefore, Pio Zirimu, a Ugandan scholar, suggested the word orature to replace the self-contradictory “oral literature.” Despite the ingenuity of the name, it didn’t really take hold, and “oral literature” is still the more popular term among scholars.

Included in oral African literature is the African heroic epic. A prime example is the Sunjata (or Sundjata/Sundiata) Epic of the Mendeka peoples, relating the legend of Sunjata, the 13th century king of the Mali Empire.

What is the stereotype about written African literature?

The oral form of African literature is frequently mentioned and acknowledged in papers and books, but even supposedly knowledgeable scholars hold the view that written African literature barely made any appearance before the 1950s (as a result of colonization). In other words, before Chinua Achebe’s famous Things Fall Apart and other African writer’s works of that era, there was no good African literature to be found. TFA was one of the first African novels to garner international critical acclaim, but was that all there was?

No, says Princeton professor of medieval, early modern, and modern African literature, Wendy Laura Belcher. She notes in her paper on African Literature, An Anthology of Written Texts from 3000 BCE to 1900 CE that while historians labor to overturn privailing misconceptions that Africa is a place without history, literary critics have done little to overturn a mistaken view that Africa has no literature. Some Westerners believe that writing done on the continent was not done by Africans or in African languages. Belcher emphasizes, and others back her up, that in fact there is an at least 3000-year history of African writing.

Why has some African literature escaped notice (or been ignored)?

Much of African literature over the last millenia has disappeared from view because it has not survived, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, but extant texts refer to these ancient documents as having existed. Second, many works were not published and therefore went unknown. Third, very few were translated from African languages into European languages, and they were therefore ignored.

As much as scholars probe and dissect shining examples of twentieth century African literature, Belcher points out there are historical precedents to the works of the prominent modern-day African writers. For example, it could be argued that the pidgin English works of Amos Tutuola (The Palm-Wine Drinkard), (which Dylan Thomas called “fresh, young English”), Ken Saro-Wiwa (Sozaboy), and Uzodinma Iweala (Beasts of No Nation) were well preceded by Antera Duke‘s eighteenth century diary, which was written in Nigerian pidgin English and carried to Scotland by a Scottish missionary. Where is that ever mentioned in popular analysis?

Historical categories of African literature

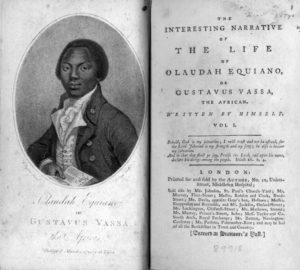

One subsection of African literature emerged from the writings of Africans living outside of Africa– both slaves and African youths whom European colonists sent to study in England, France, Portugal, Italy, Holland and Germany. The Interesting Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789), was written by former slave Olaudah Equiano, who described the awfulness of slavery and the slave trade.

An early edition of Olaudah Equiano’s autobiographical narrative (Courtesy dcc.newberry.org)

Equiano was in the forefront of the movement in Britain to abolish slavery. His book was highly influential in bringing the trade to an end. Written in English, Equiano’s narrative received much attention, but another group of Africans in Europe had writings in Latin. Those have not commanded as much close examination.

What are the ancient forms of African literature?

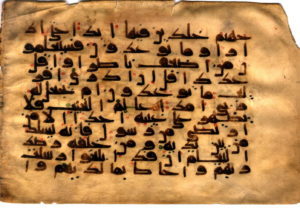

The Arab expansion in the Sahel spread Islam to the region, and the 11-century Berber-led Almoravid invasion of the Empire of Ghana (not to be confused with modern Ghana) brought with it a Kufic-derived Arabic script.

Mali, Sudan, and Nigeria developed different styles of Kufic-derived calligraphy. The role of Arabic writing and literature in West Africa has been long underestimated. Ajami is an African-adapted Arabic script found in the Swahili, Hausa, Wolof, and Yoruba. It is 300 t0 500 years old.

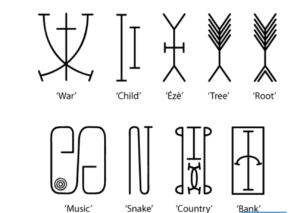

Another ancient written form in Nsibidi, which is an ideographic script with a system of symbols that was indigenous to what is now southeastern Nigeria. It dates back to at least 2000 BC.

Nsibidi, 5000 BC – present (Courtesy Atlantablackstar.com)

Many people don’t realize that the much-commercialized Adinkra symbols of Ghana also represent old, ideographic writing. It dates back to at least 1817, when the Englishman Thomas Edward Bowdich collected a piece of Adinkra cloth in 1817. The next oldest piece of Adinkra textile was sent in 1825 from the Elmina Castle to the royal cabinet of curiosities in The Hague.

Adinkra symbols recorded by Robert Sutherland Rattray, 1927. R. S. Rattray, Religion and Art in Ashanti (Oxford, 1927), 265.

1. Gyawu Atiko, lit. the back of Gyawu’s head. Gyawu was a sub-chief of Bantama who at the annual Odwira ceremony is said to have had his hair shaved in this fashion. 2. Akoma ntoaso, lit. the joined hearts. 3. Epa, handcuffs. See also No. 16. 4. Nkyimkyim, the twisted pattern. 5. Nsirewa, cowries. 6. Nsa, from a design of this name found on nsa cloths. 7. Mpuannum, lit. five tufts (of hair). 8. Duafe. the wooden comb. 9. Nkuruma kese, lit. dried okros. 10. Aya, the fern; the word also means ‘ I am not afraid of you ‘, ‘ I am independent of you’ and the wearer may imply this by wearing it. 11. Aban, a two-storied house, a castle; this design was formerly worn by the King of Ashanti alone. 12. Nkotimsefuopua, certain attendants on the Queen Mother who dressed their hair in this fashion. It is really a variation of the swastika. 13 and 14 Both called Sankofa, lit. turn back and fetch it. 15. Kuntinkantan, lit. bent and spread out ; nkuntinkantan is used in the sense of ‘ do not boast, do not be arrogant ‘. 16. Epa, handcuffs, same as No. 3.

Lybico-Berber or Tifinagh script dates back to 3000 BC at least, and is the ancient writing of the Tuareg and other peoples in Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania, Egypt, Chad and Niger.

Engravings of the Berber tifinar alphabet(Courtesy temehu.com)

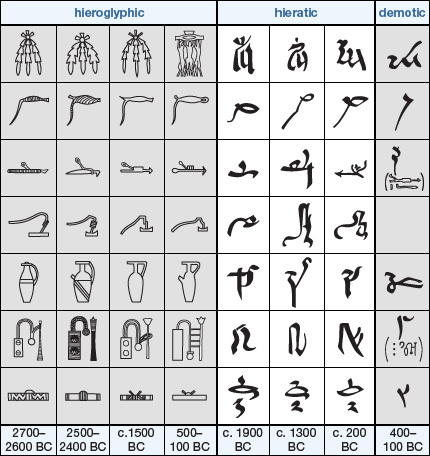

The Egyptians invented three different types of scripts–hieroglyphic, hieratic and demotic; and yes, like it or not, Egyptians are Africans.

Hieroglyphic, demotic and hieratic scripts of Egypt (Courtesy emaze.com)

Vai script (3000 BC to present) is a particularly lovely form of writing indigenous to Liberia and a small portion of Sierra Leone. It is a set of symbols representing syllables

Vai syllabary (Courtesy wikimedia.org)

Other languages with syllabaries include Japanese.

Summary

Clearly, there is much more to learn about African literature. In reference to Ajami, Serigne Kane notes, “the writings of black African authors have long been neglected due to prejudice, as both Europeans and Arab scholars with the necessary linguistic competence to study their works have often deemed their insights of little or no scholarly interest or benefit, and most assume that sources of knowledge on Africa are either oral or written in European languages,” (quote from Fallou Ngom.) Much the same applies to other forms of African writings.

Even the word “literature” seems to have been captured and held hostage by European exceptionalism as its rightful and exclusive property. African literature has been viewed as that which developed as a result of the “civilizing influences” of invading Europeans. It’s time to take the blinders off and open up the mind.

The post AFRICAN LITERATURE–Why it deserves better appeared first on Kwei Quartey .

July 4, 2017

A DEATH IN THE FAMILY

A Death in the Family by Michael Stanley

A Death in the Family by Michael Stanley

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This is the 5th novel in Michael Stanley’s Detective Kubu series set in Botswana, one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s most promising nations. This time, tragedy strikes Asst. Superintendent David Kubu Bengu when his own father is murdered. What follows is a very frustrating time for Kubu as his irascible boss Mabaku bars him from any participation in the investigation because of Kubu’s obvious closeness to the victim. I certainly felt the frustration myself. On the one hand I understand Mabaku’s wanting to make it a clean break, but I felt he could have nuanced it somewhat. Of course, as anyone who reads Kubu knows, nuance is not Mabaku’s strong point.

Like the other Kubu novels, this one is multi-pronged and complex, involving Chinese miners, government officials and village chiefs, and the way it ties up the connections to the initial murder is something the Michael Stanley duo (Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip) does very well. Despite the seriousness of the subject matter, the story does include some hilarious scenes, in particular Kubu trying to fit his hulking body into a hotel bathroom.

Sears and Trollip tell the story with obvious affection for Botswana and have stimulated my interest in visiting that country (along with another promising African country, Rwanda.)

The post A DEATH IN THE FAMILY appeared first on Kwei Quartey .

July 1, 2017

TRIALS OF A DOCTOR IN TRAINING

Doctor in training: The beginning

A brand new medical student may not think of it in this fashion, but he or she is actually a very young and green doctor in training. In medical school, there are certain main subject categories like Anatomy, Physiology, Biochemistry, Pharmacology, Pathology, and so on. A med student has to study a lot, although there isn’t as much dry reading as there is in law school, for example. In case law, you might read a case Mr. X versus the State that is page after page of long, wordy paragraphs. In medicine, cases might have images to support clinical situations and break up the tedium.

In Neurology, for instance, you have diagrams of neural pathways that you must learn in order to understand a particular neurological mechanism or disorder, as in the simplified example below. It makes understanding the pathology easier, although it doesn’t necessarily give you less to memorize.

How reflexes save us from harm (Stock photo)

Among the subjects a medical students, aka a young doctor in training, have the most anxiety about, Anatomy is probably the mother of them all. It’s the study of the structure of bodily parts and their physical relation to each other, and the study of human anatomy traditionally involves dissection of the human body much the way many of us dissected frogs or mice in high school or college. For most freshmen and fresh-women in medical school, human anatomy is the first time to see and experience a dead body. I remember I was a little apprehensive about what it would be like, but I recall some other students who were almost paralyzed with anxiety.

Group of medical students in class (Photo: Caribbean Medical Univ)

I remember the dissection hall as a large room with two long rows of stainless steel tables upon each of which was a male or female cadaver. My reaction to the bodies was surprisingly muted. They had an unreal, waxy, Madame Tussauds appearance. The skin texture was nothing like a live human. They reeked of the formaldehyde preservative, and sometimes it was so strong as to make my eyes water. In the end, I think even the students who were most worried about the cadavers got used to the idea pretty quickly, and two or three weeks in, no one batted an eye.

Each student is usually assigned to a pod of 7 to 10 colleagues who stay together as a group with the same cadaver for the duration of the semester. Each pod follows the syllabus under supervision by a preceptor, usually a junior staff physician. The study of the cadaver’s anatomy follows major regions or systems of the body: head and neck, upper limbs, chest, abdomen and so on. But within each of those are subdivisions: for example, the head and neck will include the lymphatic, neurological and muscular systems. Whether you get a male or a female cadaver is luck of the draw, as is the amount of adipose tissue your cadaver has. Consider yourself lucky if you have a lean body. They are much easier to work with.

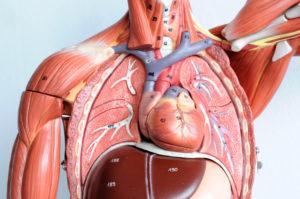

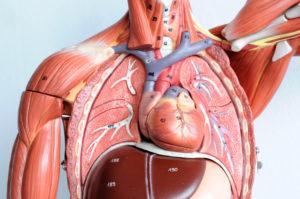

Artificial models are also used in Anatomy class (Stock Photo)

The amount of material to learn, absorb and memorize in Anatomy is staggering. A student needs to know where every nerve begins and ends, which muscles the nerve controls, the origin of every skeletal muscle and the bone on which it ends, and so on. Remember that there are something like 650 skeletal muscles in the human body. All of this information can become overwhelming, and the practical exams in which you’re faced with an unidentified organ, muscle or bone are nerve wracking. For all these reasons, Anatomy is almost certainly one of the most stressful subjects in the medical school years, but it can be also enjoyable. Most of the anatomical knowledge the medical student gains in Anatomy will stay with him or her throughout his or her life as a practicing doctor, and for those who go into surgery of any kind, whether it’s general surgery, orthopedics or neurosurgery, Anatomy is of the highest necessity.

The original “Grey’s Anatomy”

The name of the TV series “Grey’s Anatomy” originates from the all-time classic textbook, Gray’s Anatomy by British surgeon Henry Gray, with its iconic illustrations by Henry Vandyke Carter. Dr. Gray was born in 1827 and died of smallpox in 1861 at the tragically young age of 34. While still a doctor in training, Gray secured the triennial prize of Royal College of Surgeons in 1848 for an essay about the nerves supplying the human eye. His 750-page textbook, first published in 1858, is highly acclaimed to this day for its masterful descriptive detail accompanied by some 365 extraordinary diagrams.

The great Gray’s Anatomy (Photo: Barnes&Noble)

In “Grey’s Anatomy,” everyone is unrealistically beautiful (Photo: bleb.cf)

The TV program spells “Grey” with an “e,” while the textbook “Gray” is with an “a.” The 41st edition, the latest, was published in 2017. Modern versions of the textbook connect anatomy more with clinical scenarios than the old editions. By the way, I’ve never seen an episode of “Grey’s Anatomy,” where all the physicians, from the youngest doctor in training to the most senior and seasoned, are annoyingly and impossibly attractive, but I have used the textbook!

Just as in other fields like astronomy or engineering, the volume of knowledge and information in medicine seems to have increased several fold over the past decades, and has the way that knowledge is shared has also changed. In my next podcast, I’ll talk about how learning has evolved with the advent of a pocket-size device that can hold a lot more textbooks than you can lug around under your arm: your smartphone.

In a future blog I’ll tell you about the very tough years of internship and residency of a doctor in training.

The post TRIALS OF A DOCTOR IN TRAINING appeared first on Kwei Quartey.

TRIALS OF A DOCTOR-IN-TRAINING: Part 1

In medical school, there are certain main subject categories like Anatomy, Physiology, Biochemistry, Pharmacology, Pathology, and so on. A med student has to study a lot, although there isn’t as much dry reading as there is in law school, for example. In case law, you might read a case Mr. X versus the State that is page after page of long, wordy paragraphs. In medicine, cases might have images to support clinical situations and break up the tedium.

In Neurology, for instance, you have diagrams of neural pathways that you must learn in order to understand a particular neurological mechanism or disorder, as in the simplified example below. It makes understanding the pathology easier, although it doesn’t necessarily give you less to memorize.

How reflexes save us from harm (Stock photo)

Among the subjects medical students have the most anxiety about, Anatomy is probably the mother of them all. It’s the study of the structure of bodily parts and their physical relation to each other, and the study of human anatomy traditionally involves dissection of the human body much the way many of us dissected frogs or mice in high school or college. For most freshmen and fresh-women in medical school, human anatomy is the first time to see and experience a dead body. I remember I was a little apprehensive about what it would be like, but I recall some other students who were almost paralyzed with anxiety.

Group of medical students in class (Photo: Caribbean Medical Univ)

I remember the dissection hall as a large room with two long rows of stainless steel tables upon each of which was a male or female cadaver. My reaction to the bodies was surprisingly muted. They had an unreal, waxy, Madame Tussauds appearance. The skin texture was nothing like a live human. They reeked of the formaldehyde preservative, and sometimes it was so strong as to make my eyes water. In the end, I think even the students who were most worried about the cadavers got used to the idea pretty quickly, and two or three weeks in, no one batted an eye.

Each student is usually assigned to a pod of 7 to 10 colleagues who stay together as a group with the same cadaver for the duration of the semester. Each pod follows the syllabus under supervision by a preceptor, usually a junior staff physician. The study of the cadaver’s anatomy follows major regions or systems of the body: head and neck, upper limbs, chest, abdomen and so on. But within each of those are subdivisions: for example, the head and neck will include the lymphatic, neurological and muscular systems. Whether you get a male or a female cadaver is luck of the draw, as is the amount of adipose tissue your cadaver has. Consider yourself lucky if you have a lean body. They are much easier to work with.

Artificial models are also used in Anatomy class (Stock Photo)

The amount of material to learn, absorb and memorize in Anatomy is staggering. A student needs to know where every nerve begins and ends, which muscles the nerve controls, the origin of every skeletal muscle and the bone on which it ends, and so on. Remember that there are something like 650 skeletal muscles in the human body. All of this information can become overwhelming, and the practical exams in which you’re faced with an unidentified organ, muscle or bone are nerve wracking. For all these reasons, Anatomy is almost certainly one of the most stressful subjects in the medical school years, but it can be also enjoyable. Most of the anatomical knowledge the medical student gains in Anatomy will stay with him or her throughout his or her life as a practicing doctor, and for those who go into surgery of any kind, whether it’s general surgery, orthopedics or neurosurgery, Anatomy is of the highest necessity.

The name of the TV series “Grey’s Anatomy” originates from the all-time classic textbook, Gray’s Anatomy by British surgeon Henry Gray, with its iconic illustrations by Henry Vandyke Carter. Dr. Gray was born in 1827 and died of smallpox in 1861 at the tragically young age of 34. His 750-page textbook, first published in 1858, is highly acclaimed to this day for its masterful descriptive detail accompanied by some 365 extraordinary diagrams.

The great Gray’s Anatomy (Photo: Barnes&Noble)

In “Grey’s Anatomy,” everyone is unrealistically beautiful (Photo: bleb.cf)

The TV program spells “Grey” with an “e,” while the textbook “Gray” is with an “a.” The 41st edition, the latest, was published in 2017. Modern versions of the textbook connect anatomy more with clinical scenarios than the old editions. By the way, I’ve never seen an episode of “Grey’s Anatomy,” where all the doctors are annoyingly and impossibly attractive, but I have used the textbook!

Just as in other fields like astronomy or engineering, the volume of knowledge and information in medicine seems to have increased several fold over the past decades, and has the way that knowledge is shared has also changed. In my next podcast, I’ll talk about how learning has evolved with the advent of a pocket-size device that can hold a lot more textbooks than you can lug around under your arm: your smartphone.

The post TRIALS OF A DOCTOR-IN-TRAINING: Part 1 appeared first on Kwei Quartey .