David duChemin's Blog, page 7

October 14, 2016

The Vision Collective

Big News. Free eBooks. Huge Charity Impact. And your only chance to join me for a 26 week course that’ll change your photography forever. Only for the next 5 Days.

This year’s 5 Day Deal just started and again we have a chance to raise some incredible money for charity and save some huge bucks on some exceptional photographic resources. In short: over $2500 worth of photography education for only $97. For 5 days only.

But the longer story is better than that. It begins with a great deal, for sure. And the money raised for charity, including for the Boma Project with whom I work so closely, is incredible – think 6 figures. Amazing. But wait! There’s more!

First, we’re conscious of how many sales messages you get everyday, some of them from my team at Craft & Vision. We don’t love the noise these sales create. So we’re going to try to offset that noise, or at least make it the kind of noise that you hear coming from a great celebration. Here’s what we’re doing, in addition to asking to asking you to consider looking at the bundle and buying it through the links on this page.

Today we launched a new eBook and it’s yours completely free. It’s called Master The Craft, 8 Step to Becoming a Better Photographer. It’s no War and Peace, but I’m hoping it’ll serve you well as you move down the path on this journey. Get it here by signing up for the Contact Sheet, and we’ll send you the link.

Every day we’re sending out the Contact Sheet, an email newsletter from Craft & Vision, and with it we’re sending new free resources everyday – 12 in total over the course of this sale. Not a subscriber – make sure you’re on the list here (and we’ll send you a link for the free Master The Craft eBook). And yes, if you really want to you can unsubscribe at the end of the sale. But we’re hoping you’ll like our stuff enough to stick around.

Today I’m launching The Vision Collective. The Vision Collective is a 26-week email course designed to push you deeper into your craft, to help you refine your vision, and create more intentional work. Each week I will send you a new lesson about a subject that takes you into the real work of creating compelling photography (for example, subjects that center around storytelling or visual design), and included in that lesson will be a new creative exercise to push you a little further, and an introduction to masters of this craft to help you study work that challenges you and builds your visual literacy and repertoire.

Designed not to be overwhelming but to take you deeper and push you harder, The Vision Collective brings focus to your training as a photographer. No gimmicks, no platitudes or shortcuts, just solid teaching about your vision and your craft. And – here’s the important part – it’s only available through the 5DayDeal, and only for the next 5 days.

Your next steps?

Get the free eBook, Master Your Craft, by making sure you’re signed up to get The Contact Sheet (many of you already do, so no need to do anything more – you’re in and should have already got an email with a link). And then check out the 5 Day Deal – if you want to be part of The Vision Collective, this is your only chance.

This sale, as I said, raises a ton of money for some very good causes. I make money as an affiliate and it’s from those sales I pay for my pro-bono work for The Boma Project, one of this year’s 5DayDeal Charity Partners. Thanks in advance for considering this, and for being part of what I do. If you want to share the love even more, share this post with the social buttons below. Thanks!

Share this Post

October 6, 2016

My Fuji Menu Settings

This is a short one. I’ve had a handful of questions asking me how I set up my Fuji cameras and as I set them up almost exactly the same way I’ve always set up my digital cameras, I thought I’d address it here. Don’t let the title fool you, this applies to almost every camera I’ve used in one way or another.

We live in an age of ever-increasing options. Options add complexity, and once in a while I am grateful for those choices. However, it’s important (at least for me, and the way in which I create) to remember that what I most want is for my gear to do what I need and then get out of the way. So for me simplicity is key. I just want my cameras to do what they have always done: make the photograph I ask of it and not to second guess me or make me look stupid.

I shoot my Fuji, and almost every camera I’ve used, the way it comes, straight out of the box. Here, as I recall, is what I change:

Set Date and Time (with terrifying inconsistency)

Set RAW + JPG (F)

Set Card Slots to Overflow (first fill one card, then fill the other. I don’t sweat the need for redundancy, never having had a card fail)

I use Auto WB. Almost always.

I often use my film emulations if I want to use Acros (B&W) or Velvia (rich slide film, dark shadows) – so one of my buttons is customized for this.

I often use alternate crops, specifically 1:1 or 16:9 so one of my buttons is customized for this.

I set my Fn button to activate my Wifi connection.

I like to see my histogram and a grid in my viewfinder, so I make sure I can see those along with my ISO, aperture, and shutter speed.

That’s it. So when I pick up any of my cameras they all do the same thing. There are no surprises.

I switch frequently between AF-S, AF-C, and M to focus and I move my focus point around when I need to.

I expose manually most of the time. And use centre weighted metering, though I really no longer meter so much as I watch my in-viewfinder histogram in which case my metering mode is irrelevant. Point the camera at the scene, read the histogram, expose depending on which details are more important, highlights or shadows.

I throw my ISO around like a cheap carpet. That’s one of the reasons I like the X-T2 – it’s much easier to dial this in without thinking about it.

But all the other stuff? I don’t use it. If it works for you, do it. But try to remember that a camera is a camera and the only thing – the ONLY thing – that matter is this: does it make the photographs you ask it to make and does it get out of the way when you need it to?

All I really want is a shutter speed, an aperture, and ISO, and critical focus. And I want to get there as fast I can without having to think much about it. The rest is composition and timing, patience and creativity. It’s story, moment, emotion. If you shoot in such a way that you need to tweak the sh*t out of your menu settings, do it. But then you probably already know that. If you don’t, then stop screwing around with your menu and start looking through the viewfinder and experiencing the world around you. Worry later about sharpening and contrast and whatever other setting that’s getting you bent out shape. Now is not the time. Now is the time for experiencing and perceiving and interpreting. Wait for the light. Wait for the moment. Don’t sweat the little things – because if it’s those little things that carry the photograph for you, you probably need a stronger photograph, not a sharper one. And that’s never a matter of menu settings.

Questions?

Share this Post.

September 30, 2016

Best Places

After several years of photographing some truly wonderful corners of this planet I get more than a few emails each month asking me where are the best places to photograph in this city or that country. I try to reply helpfully, but what I want so much to say, without sounding like I’m being contrary, is this: there’s no such thing as best places. There are wonderful places, to be sure. There are popular places, and busy places. There are places that appeal to some and not to others. But photographs happen at the intersection of place and light and moment, and the corner in Venice that for much of the day is flat and crowded and in all ways uninteresting, might for one moment on one given day give the photographer a gift he never dreamed. And the must-see list from the Lonely Planet might give us nothing.

I can give you lists of the places I like, but I like them for so many reasons and at such specific moments, that those lists would be no good to you. They would encourage you to buy the illusion that you just have to show up at the right place with the right lens and make the same photographs I’ve made. And just maybe that happens. And then you’ve made a photograph someone else has already made. Now what?

More harmful in the act of giving you that list is that it won’t encourage you to do the one thing that will give you both unique and unexpected experiences and the photographs that come from those experiences, that is the act of getting lost. Of having your own experience. Of being forced to encounter a place on your own terms and make the kinds of photographs only you can make.

There is a heartbreaking tendency in photography towards the homogenous. Nothing would make me sadder as a teacher than to inadvertently push you in that direction. So, to put a more positive spin on this, when you next ask me where the best places are, here is my answer:

The best place is the place in which you experience wonder, where your eyes are open to things you’ve never seen. The best place is the place in which you are lost, beyond your notions, a little off-kilter and looking for balance. They are places full of possibilities and unhindered by the need to make a photograph just like the ones you came hoping to make, but instead make something more, something better than your expectations.

The best places are within; places of receptivity and possibility, of courage. They are places into which we go empty, and emerge filled. You will find none of these on a map, or in a guidebook.

They are places to which, often, you can never return, and to which no one but your curiosity can lead you. And I want so much just to be able to put my finger on map and say, “Here, friend. This is where the magic is.” But whether it is or it is not depends not on the place but on the eyes with which you see it.

Share this Post.

September 13, 2016

Photographing Wild

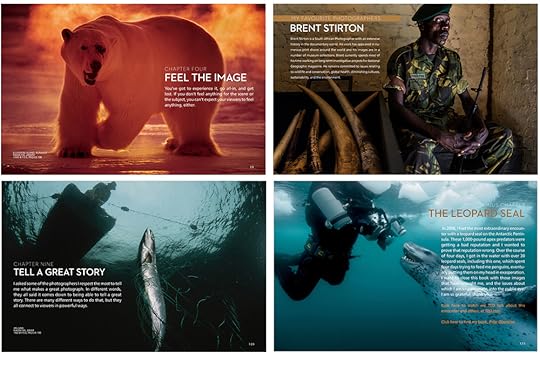

National Geographic Photographer Paul Nicklen is an astonishing photographer. What he does to make his photographs makes most of us look like dilettantes: we worry about getting to a location before sunset while Paul swims with killer whales, dives with Leopard Seals, and hangs out beside Spirit Bears while they eat. These things put him in places to make the extraordinary photographs he makes, and most of us aren’t going to go to the same lengths, but the principles that guide his work can guide ours, and help us make stronger photographs, no matter what the subject matter. Paul makes the photographs he makes because he understands it’s way more than how well he uses his camera.

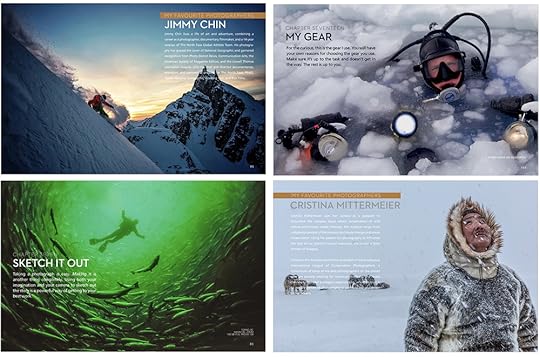

Photographers like to put subject matter into categories, so it would be easy to consider Paul’s new eBook, PHOTOGRAPHING WILD, Techniques of a National Geographic Photographer, a book only about wildlife photography. That would be a mistake. The book is written by a man who is deeply passionate about conservation issues, to be sure. And most of the photographs that so lavishly illustrate the book are made in places many of us will never be. But the 16 techniques Paul shares will help you make stronger images no matter what you photograph. Whether your subject is a bear or a human being, whales or street culture, visual storytelling is visual storytelling.

It would be easy to consider PHOTOGRAPHING WILD a book only about wildlife photography. That would be a mistake.

What impressed me most over the months we collaborated with Paul on this book was how hard he works. He is a talented man, there’s no doubt about that, but he didn’t get through the doors of National Geographic on talent alone. In fact he practically beat his head against the door until someone finally opened it and gave him his chance. I think that gives us all hope. The techniques he discusses in Photographing Wild come from that work ethic and from learning his craft in one of the hardest, most demanding schools there is. There are no secrets, no gimmicks, and platitudes; just real world advice from a guy working his ass off for a magazine that routinely reminds its people that they can’t publish excuses. I have learned more about my own craft and what it takes to make the kind of visual experiences I want my photographs to be, from working with Paul over the last six months, than I have in a very long time.

There are no secrets, no gimmicks, and platitudes; just real world advice from a guy working his ass off for a magazine that routinely reminds its people that they can’t publish excuses.

Photographing Wild is a 200-page PDF eBook featuring (among others) some of Paul’s best-known work with Leopard Seals and Spirit Bears, as well as the input of some of his colleagues at National Geographic: Joel Sartore, Jimmy Chin, David Doubilet, and others, all of them legendary photographers weighing in on what makes great photographs and great photographers. This eBook is also a chance to partner with Paul in his work: for every copy sold, 40% goes to Sea Legacy to help Paul, and others, continue to speak for the oceans and those that dwell under the thin blue line.

Photographing Wild is a 200-page PDF eBook featuring (among others) some of Paul’s best-known work with Leopard Seals and Spirit Bears, as well as the input of some of his colleagues at National Geographic: Joel Sartore, Jimmy Chin, David Doubilet, and others, all of them legendary photographers weighing in on what makes great photographs and great photographers. This eBook is also a chance to partner with Paul in his work: for every copy sold, 40% goes to Sea Legacy to help Paul, and others, continue to speak for the oceans and those that dwell under the thin blue line.

Photographing Wild is available today, on sale for just $10 (reg. $15) until September 24.

I don’t often do much more than post a quick blog post and let you know a new resource is out there. But this time I’m going to ask you directly to please consider buying this eBook. Do it now while it’s on sale. What Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier are doing with Sea Legacy is incredible and doing this ebook with them is a way I can be involved with that. I want you to buy this book because it’s an excellent book, filled with a lifetime of experience and incredible photographs. It’s also a chance to do some good. And then, would you share this post, tell others about it on Facebook or whatever your social media circles include? Share the video, give it a FB like, share the love in some way. This is a chance to make better photographs and a better world and that doesn’t happen too often.

Spread the Word!

September 9, 2016

Seeing Colour

This image is a photograph of two black gondolas on black water.

We do not see things as they are but as they look, and the brain will do whatever it can to untangle puzzles like this. So many people will walk past this scene and others like it and never see it. Not truly. They will see it at they think it is. Black boats on black water. But if we force our brains to look twice we see blue gondolas on a sea of yellow, red, and green, reflections from the brightly coloured hotel on the other side of the canal.

Venice, Italy. Posted twice for the sake of people getting this feed by RSS or email subscription.

The brain is what it is because of a long evolutionary process that had survival as its goal. The brain did not evolve to serve our photographic needs, nor our artistic ones. The chief creative struggle is to get the brain to work against what it has evolved to be. To overcome fear, to see things differently, to take our time, to do things that are not at all relevant to our survival as a species.

That’s why photographic seeing is so hard. It’s not about seeing at all. It’s about perception. It’s about training the brain to see what is really there, in the otherwise unimportant details. It’s about nudging the brain to think differently, to see important details in what is otherwise trivial. To allow itself to see the colours as they are and not worry about what might leap from the water. This is one reason we don’t see lamps coming out of someone’s head – we’ve seen it, judged it as unimportant and focused on other things. Same with reflections. Same with shadows. In fact almost anything we see that might be interesting photographically needs to be re-interpreted by the same brain that’s working so hard against us. It’s trying so hard to survive. We’re trying so hard to make a photograph.

So we need a firmware upgrade. And that takes time. But it can be done and the best tool for that is questions. Asking yourself to constantly re-assess what you see. What is the light really doing? Is it giving me colour I’m not seeing at first glance? Is it giving me shadows I didn’t notice? Is it creating reflections? Have you ever noticed how blue a shadow in snow can be? The more you notice these things and take note of them the more open your eyes will be, metaphorically speaking. Seeing is about recognizing. The way to do this is to keep noticing what is really there. To take notes in that brain. To remind your brain that our new priorities include the artistic and the creative. The brain is easily re-wired through repetition, it will notice new things with practice. That’s what learning to see is about. Learning to recognize what is, and helping the brain to stop interpreting things with such a “survival at all costs” paradigm.

The world our brain expects to see, and the hazards for which it looks, has been gone for most of us for a long time. If we’re going to see things as they are, and put those things into our photographs in more than an accidental way, it’s going to take a little adjustment. Ask your brain to look again. Ask more questions.

Tell Your Friends.

September 5, 2016

The Photographer’s Tools

I believe now more than ever in this beautiful craft. I love its democratic nature, I love the way it uses such elegant raw materials: light and time. I love the mechanics, and the way the cameras feel in my hands. And I adore the final print. In fact the moment I’m done writing this I’m going to run some overdue prints, just for the joy of seeing them emerge in the real world in dark black and graceful greys.

I believe we can experience photographs in a way that we don’t experience other mediums. They stick in a unique way. Or they can. But that stickiness isn’t innate. We have to put it there. And the tools to do so are not the camera and the lens, much as I love them.

The tools of the photographer are her language and not the camera itself.

I mentioned this in my last article, The End of What it Looks Like, but I’ve been thinking a lot about this between this post and the last. You know, we talk a lot about writing with light. It sounds poetic. But we talk so seldom about what we write and how we order the words to best say the thing we envision. We know our f/stops by memory, and we can talk for hours about the latest advances that make it easier than ever to make sharp and well-exposed images, but ask us about balance, tension, colour palettes, and other elements of the visual language and we’ll look at you like you just licked our sensor.

Our cameras are not our tools. The elements of the visual language are our tools. The craft of photography matters deeply and you need to know how to use the mechanics, but that’s just the price of admission. It is assumed that you will learn how to use the hardware. But using the hardware is not the same as saying something. It’s not, as I said, where the stickiness comes from. That comes from someplace deeper, and it comes only through the use of intangible tools like contrast, scale, repetition of elements, and the way we use the frame itself. It comes from how we create energy and mood and story. Your Nikon can’t do that. Only you can do that.

We will always have room to grow in terms of our craft. Over 30 years on and I am still finding new ways to use the fundamentals of the mechanics of this craft. But that is not the goal. The goal is more; it’s bigger. The goal is to learn every day to see in new ways and experience this world with wider eyes. It is to find new ways to express that, and new ways to tell stronger stories. So here is my challenge to you because it might be time someone told you: stop screwing around with your gear and start to learn the language. You’ve got something to say, I know you do.

Learn why the orientation and ratio of your frame helps tell your story. Learn how to use scale and proportion. Learn to tell stories. Learn about colour. The mechanics are the tools of craft, but the language is the tool of art. Get fascinated by that. Go to a gallery and learn about the visual arts. It might be intimidating, learning always is. But find out why Van Gogh did what he did, and why it worked. Pick up a book about Picasso and learn about his use of line and shape, or about Rothko and his use of colour. Or about graphic design. Buy a visual art or graphic design magazine next time you’re tempted to buy yet another photography magazine. How many Tamron ads can one person absorb, anyways? Consider studying my book Photographically Speaking, or Molly Bang’s Picture This, or Michael Freeman’s excellent book, The Photographer’s Eye.

You’re probably pretty good at focusing and exposing. You’ll always get better. Now it’s time to study the harder stuff. Who’s in?

Share this Post, Share the Love.

August 30, 2016

The End of What It Looks Like

I’m in Melbourne right now – my first time to Australia, and my 50th country. I’m speaking at the Nikon AIPP, an incredible convention filled with some wonderful people. Yesterday I gave the keynote address that opened the conference; it’s a fearful task to inspire people at 8:30am. It was a presentation I’ve been obsessing over for a couple weeks and it was good to stretch myself, to risk, to wrestle with the fear again. It’s too easy in the creative life to find the little pockets of ease and comfort and hide out there. This article comes out of that presentation.

A couple years ago the number being floated around about photographs on the internet was this: 1.8 billion images a day were being shared on social media channels. All of them showing us what every minute corner of the world looks like. It is safe to say that there is little – if anything at all – that remains to be shown. Do a Google search for any conceivable thing, place, or person and there’s a good chance you’ll get more images than you can use. This used to be the job of photographers, particularly the so-called professionals: to illustrate. To show the world what it looked like.

In order to show the world what it looked like the photographer had to use a rather technical means, had to understand the physics, the chemistry, the optics. Owning and using the gear required was not easy. This was the means by which the photographer accomplished his craft and remained relevant. And that, for generations was the task of most photographers – to use complicated gear to show the world what it looked like.

Can you see where this is heading? Something only has value when it’s needed. When it’s scarce. And you can say neither about the use of the camera nor the need for more illustrative images of a world in which 2 billion photographs are shared, not to mention the ones not shared, every day. Before you despair or rush to the ramparts to defend this craft, let me say that I believe more than ever in the value and need for photographs. It just isn’t where it once was, in illustration.

The extraordinary opportunity now available to photographers is not illustration but interpretation. Of course there have been photographers for the entire short history of the craft that have done this, transcended craft and made art, showing the world not only what it looked like, but what it felt like, and – to some degree – what meaning could be found there. But they have been fewer. We need them now more than ever.

This is where we will find relevance. The world already knows what it looks like. It has seen itself from every angle. What it needs now, more than ever is to see itself in new ways. Ways that give it hope. Ways that don’t let us flinch and look away when we see the bits we don’t like. Ways that show us, also, the beauty. Ways that engage us and stir our imaginations. We need photographers now to stop seeing their cameras as their tools. They aren’t. The tools of a photographer are the tools of visual language, just as the true tool of the writer is not the keyboard but the words themselves, all of them combinations of the same 26 letters. The magic of the writer comes not in her ability to pound the keys but to form words and sentences that say something, that transport us, that stir imagination, that light a flame in our heart. It is not that they can write something, it’s that they have something to say.

Our photographs may be worth a thousand words, they might not be worth the paper upon which the words are written: what matters is what is said. So why are photographers so late to pick up on this? Well, for one, they aren’t. Not all of them. We have a rich history of people, both men and women that have used the camera with such courage. But for what is arguably the vast majority of photographers it is this: it takes guts to put yourself out there. It takes risk. It takes having an opinion in the first place and it takes an attention to the soul of things that is so much harder than just learning the Zone system. Our history is full of voices telling us to shoot not what it looks like but what it feels like. It’s time we paid even more heed to these voices.

It’s very, very noisy out there. The noise is only getting worse. And the only way to cut through that noise is with signal: with something to say. And the more human that thing is, the more it will connect, because that humanity and connection is the rarest of commodities. Our calling, as my friend John Paul Caponigro reminded me recently in an article he wrote on Abstraction is so much more than craft: “there is a world of difference between focusing a lens and focusing attention.” To do this we need to experience the word deeply, to live and love deeply, to commit to something, to open our eyes so wide it hurts. Vision, as Jonathon Swift reminded us, is the ability to see what is invisible to others. The calling of the photographer is to see the invisible and to show it to the world, and those are the things we see not with our eyes so much as with our heart.

I don’t know how you’re going to do it, the “how” has been the struggle of every artist for as long as art has stirred in the human heart and imagination. But I do know that for most of us, if we want to be heard, we need to find a way to dig a little deeper, we need to expose our hearts and souls more than we expose our film or sensor. We can’t show the world what it feels like until we feel the world deeply ourselves and have the courage to share that. That is how we cut through the noise. That’s how we remain relevant. The world knows what it looks like. It’s time to go deeper.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

August 25, 2016

Exposing for Highlights

While people rush to buy the latest cameras with the highest dynamic ranges and the latest software that’ll allow simulation of the highest dynamic range possible, and there’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, it helps to remember that every limitation can also be a beautiful creative constraint.

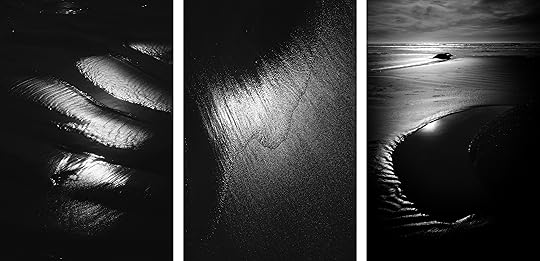

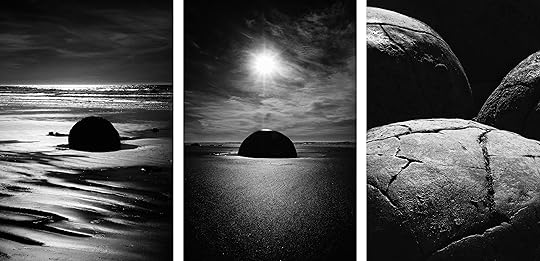

On the beach in Moeraki recently, and disappointed by the bright sunlight and apparent lack of mood I took advantage of the fact that my sensor can’t capture all the light that’s there. Not remembering to take a reference photograph, it’s hard to show you what things looked like but I can show you what it felt like to me because I was looking at the sun sparkling on the sand and to do that I had to allow everything else to go dark.

The technique is simple: expose for the highlights, the bands of light that would otherwise be too bright if I had exposed for the rest of the scene. The result is a histogram that preserves the details in the brightest places and allows the shadows to go to black, the reverse of what one might instinctively do in this scene. Or underexpose the scene by about 4-5 stops. Just keep going until the histogram shows no lost details in the important highlights (or fewer of them) – for me that was the parts of the image where the sun was rim-lighting the rocks or reflecting most directly on the sand. What I was drawn to was the elegant tones and texture of the sun directly hitting the sand, and this was a beautiful way of showcasing those. The results are rich and moody, shot directly as black and white images using the Acros film emulation on my Fuji X-T2. No filters, no post-processing other than a few nudges in Snapseed on my iPhone, just elegant, dramatic, black and white using old-school underexposure.

Hey, as a reminder, and to those that aren’t in the know just yet, I will be splitting my attention between this blog and the Craft & Vision blog where you can read articles from me, interviews with interesting photographers, and insights from C&V authors like Piet Van den Eynde. Please check it out.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

August 17, 2016

Cringe

I often look at the work of a younger me and cringe at his decisions. His choice of moments was hurried and impatient. His composition was simplistic. His use of colour and composition was undeveloped. My god, he barely seemed to know what he was doing. No wonder he spent so much energy trying to convince himself he wasn’t an imposter, that he belonged in this world if not by virtue of talent then at very least by the strength of his desire. On good days that act of looking back isn’t so much to put down the artist I once was, but to celebrate how far I’ve come. That sub-conscious cringe is a sign that I’ve grown in the ways I see and experience the world, and in the ways I express that with the tools of my craft, such as they are. On the bad days that cringe fuels my suspicions that I’ve sucked all along and I probably suck now too, if only I had the eyes to see it.

Lately the good days outweigh the bad. But the cringe remains. It keeps me humble and grounded. It helps me see the younger me with more patience and compassion, and gratitude because we all need to suck for a while. It’s how we learn. And younger me put in the time, and took the risks, and made some truly atrocious photographs. I am reaping the benefits of that now, as older me will one day reap the benefits of the risks and failures I experience now, the same ones that still make me wonder if I know what the hell I’m doing and just want to toss the gear into the river. Future me will be very grateful I don’t do that, but that I persevere instead, that I see where this is leading me.

The cringe is a beautiful but awkward signpost. It means we’ve grown. It means we care. It means our eyes are open. It means we have, at least on more enlightened days, the humility to see the cracks and the flaws in both the art and the artist. It means we have hope. And yes, the work we’re so proud of now will be the work our future selves looks at with more mature eyes; it’ll be work that elicits the occasional cringe. We should be so lucky. The alternative is stagnation, and eyes that grow dull with age, seeing less not more. As uncomfortable as that cringe can be, it’s a celebration of how far we’ve come, and how far we might yet go.

Share this Post, Share the Love

August 9, 2016

The Craft & Vision Blog

I took much of last week off to get some needed work done on the Craft & Vision website. Part of that overhaul was the addition of a Craft & Vision blog. When we decided with some sadness to retire PHOTOGRAPH Magazine we knew we wanted to keep parts of it alive. The magazine was a success, but an expensive one. The blog aims to keep giving you the best of PHOTOGRAPH without us having to sell the farm.

Our initial goal is to publish great articles from our community of authors, and short interviews with photographers doing interesting things, so we can introduce you to their work. Keeping with our name, there will be some technical articles about the craft alongside articles about vision and the creative process. We won’t overwhelm you; we aren’t trying to be PetaPixel. We just want to keep building the community and serving you as best we can. We’ll start with about 3 articles a week.

I will continue to write here. I’m enjoying the sanity of the once-a-week kind of stride I’m hitting. But I will also be posting on the C&V Blog. We’re hoping a diversity of content will bring more people into the fold. As part of that we also want to celebrate the work of photographers in the C&V community. We’re still working on how to do that but for now we’re starting with Instagram. Check out today’s blog post for details.

Right now there is a great article about using Target Collections in Lightroom, an Interview with Cristina Mittermeier, and a review of the Epson P800 printer, along with a handful of other articles, with more to come. Do me a favour and check it out, and if an article strikes a chord we’d love it if you hit one of the share buttons at the bottom, or commented to let us know you’re out there. More to come, thanks for being part of this.