David duChemin's Blog, page 10

April 11, 2016

Vision Is Better, Ep. 38

This week I indulge in a passionate rant about what it takes to be a so-called Professional Photographer. Join me as I discuss value and the need to serve an audience. Is it realistic to expect to make a living as a professional photographer? It is. But you better enjoy the struggle and you better be willing to become an entrepreneur because it’s so much more than just making photographs.

In this episode I mention two of my books, the first is VisionMongers, Making a Life and a Living in Photography – available on Amazon here

I also mention How To Feed a Starving Artist, available from Craft & Vision here.

Got questions about this video or ideas related to making a living in photography, leave them in the blog comments, I’d love to discuss them.

April 6, 2016

More Than Wow.

I used to be a magician.

An honest-to-God, I-do-this-for-a-living Magician. And a juggler too. And a comedian. But let’s talk about the magic part. I spent a lot of time by myself, learning how to hide coins and cards and make birds appear from nowhere. I had an illusion built that allowed me to cut myself in half on stage. At one point I opened my show by pulling a large, heavy, bowling ball from a thin briefcase. I could do some cool sh*t, man.

But it was all just an illusion. Well-practiced illusion that took a lot of time, effort, and sometimes money. And some people, usually the under-7 crowd, thought I was really cool. Because I could do cool stuff. Don’t even get me started on how I ended my show with a straitjacket escape or riding a six-foot unicycle while juggling flaming torches, or how I could steal a watch from someone’s wrist. Like I said: cool sh*t was done, and I was the doer.

I was not alone. Sometimes I went to magic shows and magic conventions where other doers of cool stuff gathered. Most of them did cooler stuff than I could dream of. Most of them knew it. They traded in secrets and had secret-sounding names like The Incredible Jimmy or the Mysterious Mike. Most of them knew more about the dark arts (the dork arts?) than they did about the deeper mysteries, like, you know, talking to girls. We traded not in wonder but in cheap parlour tricks. We got off on the very temporary, stunned, reactions of others. If you know me at all it shouldn’t surprise you to know I bored of this quickly and wondered if there wasn’t more to it.

And then one day I went to a Cirque du Soleil show and saw a guy fly. For real. And my heart leapt. There was no magic – I could see the thick wires above the stage, no effort made to conceal them. But there he was flying all the same. It was part of a story so compelling that the how was irrelevant. And there was no applause cue, no “look at what I can do.” Just wonder. It bypassed my head and went straight to my heart and I didn’t jump straight to “how did he do that” because how he did it wasn’t remotely relevant. The story mattered. The wonder mattered. It’s stayed with me – that feeling – longer than any magic trick I ever saw.

Photography, and probably almost any art, has its own cheap tricks. We rely on them when we miss the moment, the story isn’t compelling, the light’s not “popping”, or our composition doesn’t quite work. We polish our turds furiously in the hopes that they’ll look better with a little misdirection. And they do. But they get a “wow” and are immediately forgotten. We sharpen, we saturate, we HDR, we filter, we Photoshop Action the shit out of photographs that never had a chance because they never had a heart, a story, a vision. They are met with the kind of wonder reserved for those that don’t know it’s just an illusion, it’s brief, and it’s uninspired, and worse: it’s uninspiring.

We polish our turds furiously in the hopes that they’ll look better with a little misdirection. And they do. But they get a “wow” and are immediately forgotten.

I’m not writing this so much as criticism for others (though perhaps an observation) but as a reminder to myself to remain defiant about these cheap tricks (because I’ve had my share of them), to settle for nothing less than images that are honest and good because they connect in truly human ways, that tell stories and affect change, and embrace craft not gimmicks. This becomes more and more important because in the high-noise / low-signal times in which we create and share our photographs we will see a law of diminishing returns at work; it will take more and more saturation, more sharpness, more dynamic range and more flavour-of-the-day to get and keep the attention of others, until our senses are completely numb. I don’t believe these diminishing returns affect good storytelling, and honest humanity. We have hungered for them for centuries despite an endless supply.

It will take more and more saturation, more sharpness, more dynamic range and more flavour-of-the-day to get and keep the attention of others, until our senses are completely numb.

What it takes to get past this stage – and most of us go through it at least once if not cyclically – is a desire for more. For deeper images. And a willingness to see the flaws in our work, the laziness in our craft, and the compromise in our vision. This is not always where I am, but where I strive to be. This is the journey, not only of photographic vision but of craft and art, and the connections that those things make possible. And maybe not everyone wants that. Maybe not everyone is there yet – it’s taken me 30 years to get to this place. But there’s got to be something more than wow, more than “how’d he do it?”

*A note. This isn’t about HDR. Or saturation. Or Photoshop. It’s about the use of tools and gimmicks without a purpose, without a heart, and without the desire to give our art, and our audiences, a chance at something more. It’s about the desire to give them something more than the photographic equivalent of soda pop.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

April 4, 2016

Two Things. One of them is free.

Thing One: Today I released Episode 37 of the Vision Is Better show (watch the embedded video above) – thanks so much to all of you who left feedback recently. Embedding this on the blog never occurred to me but if it’s preferred, I’ll try to remember to do that for you. Join me as I discuss the one thing that I think will help keep you in the moment longer, and give you more attention to direct to your creative process and composition.

Thing Two: I’ve told you about Artifact Uprising before and I’ve done my best to try to convince you to print your work, either yourself or through a service. I love the Square Prints at UA – they come in packs of 25 and they can printed directly from your Instagram feed, which makes it easy to not be that person whose work is only ever in digital form. Print them, carry them around, give them out. Leave them on coffee tables. Write on the back of them as thank you notes. Or just keep them and enjoy doing what too few of us do: holding our work in our hands. I have hundreds of these great prints. Until April 10 if you use the code DAVID25 you can have a set of 25 Square Prints for free (a $21.99 value) – you just have to pay for shipping. Head over to Artifact Uprising to get your print on.

March 30, 2016

Tell Me a Story

I just finished reading a book about the power of story. Another one. I keep coming back to this topic because I can’t escape the feeling that photographers are missing something. Sure, we acknowledge that some of the best photographs tell, or imply, a story. But it usually ends there. I think we can do better.

The book, The Storytelling Animal, by Jonathan Gottschall, reinforces the notion that story is central to our lives. In a very real sense we live for story. It gives us meaning where there appears to be none. It gives us direction. Teaches us. Inspires us. And we are surrounded by it. Narratives are everywhere, not the least of which are advertisements. And then I read an article about the rise of Instagram and something clicked for me. The article was, in short, about photographers – so-called Instagrammers – making a decent living as storytellers for major brands. The click: it is not only the power to make a single photograph that makes this new brand of photographer successful but the power and intent to make a single narrative out of many of them. A narrative we want to be a part of. A story that touches some longing in us.

If your goal is to connect with an audience, and to engage with them on some level then the stronger your story, the deeper your connection will be.

You may not like Instagram. I, despite my initial desire not to, love it. But I got on there and found – to my horror- that the best of the people I follow there have me hooked. There’s something in their (well-curated) lives that I want. Their style. Their passion. Their adventures. Their well-chiselled abs and yoga poses on impossibly serene beaches. Why? Because they are telling me a story. And I am – you are – hard-wired for story.

The take-away for me is this, and it’s been building a while: if your goal is to connect with an audience, and to engage with them on some level then the stronger your story, the deeper your connection will be. What does it mean to be stronger? More vulnerable. More consistent. More tightly curated. I am not arguing for such a tightly edited version of your life that it’s inauthentic, quite the contrary: the more authentic the storytelling, the more authentic the connection. Take away what is fundamentally not the story.

What’s your story? And to whom do you tell this story? Does your portfolio help tell the story? Your social media feeds? What about your headshot? Let’s talk about photographer’s headshots as a good example, because – real estate agents aside – I don’t know that I’ve seen an industry so in need of a headshot reformation (forgive me if you are not a photographer, but I think you’ll get the point all the same.) What does your headshot say about you and the story you are telling? Is it just you with a camera? That’s not a story. Well maybe it is, but it’s not much of one. In a world where billions of people have a camera, there’s not much compelling about the fact that you have one too. Here’s a start: show me the story you are living. Show me your personality. In some photographers’ headshots the camera seems to be the main point and I could, forgive the expression, give a toss about your camera. Give me something to connect to.

Who are you? What’s the story you are living and the story you are telling? Who is your audience? Now take away everything that’s not part of that story, and tell the most passionately, tightly-edited, authentic, vulnerable version of that story. Will it work? Well that’s a bit of a ruthless question because for most of us, we just long to tell the story, results be dammed. But yes, it will. Because as hard-wired as we are to tell stories (though we have to learn to do it well), we’re hard-wired to receive them. We hunger for them. Every advertiser on the planet knows and leverages this.

When I was in grade 7 I found a poster on a wall for a man named Guru Dev. It said: “I will not teach you Yoga. I will teach you love. Love itself will teach you Yoga.” Thirty years later I still roll my eyes. But my version rings true, and less creepy, too: don’t try so hard to sell me your brand. Tell me your story. Your story itself will sell me your brand.

Whatever you’re trying to share with the world – your photography, writing, business idea, or clothing brand, don’t tell me what to think, do, or buy: tell me a story. You will, I hope, find my story all through this blog, and my photographs. I’m beginning to put some of my stories on Maptia.com, including the featured image for this post which came from an epic trip across Canada, and a story I called 22,000Km Home.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

March 28, 2016

Vision Is Better, Episode 36

Good morning, all. I’ve been working for months, on and off, on this YouTube show, Vision Is Better. I’ve linked to it before but I want to embed it here on the blog to give more people a chance to watch it. The hardest part of this thing, technical learning curve aside, is coming up with ideas to discuss on a mostly weekly basis. Do me a favour? Watch the video. Then subscribe. And then if you really want to help me make this as useful as I can for you – would you leave a comment here or in the show comments and tell me what you’re struggling to learn right now? Questions about your vision, your craft, your gear? I’d love to hear it. There are 35 episodes before this one, enjoy!

March 24, 2016

Image or Imagery?

Each time I travel I get the same questions about my gear. Here are the answers. But I should warn you, this post quickly turned into a bit of a rant.

What Camera do you use? Right now it’s Fuji mirror-less for the most part. And a couple zoom lenses from 16mm to 90mm. Sometimes longer. But it could as easily be Sony or my old Nikons. Yes, I love my Fuji gear, but ultimately it doesn’t matter. I used to look like a much cooler photographer, but I make better photographs now because I can walk longer and farther and my gear gets in the way less. Find the camera that works for you, then use it.

What Camera Bag do you use? I travel with my gear in a Think Tank Airport Essentials bag. It’s a great airplane bag. When I get where I’m going I pull two bodies and two lenses and put them in one of two lightweight satchels I own. One is simple leather, floppy and boring, with no bells or whistles. The other is canvas and has a couple pockets, and is made by Filson. Neither are camera bags. There’s no padding or dividers. I throw a sweater or rain jacket in, put in one camera, a couple spare batteries, and a memory card wallet, and walk out the door with the other camera slung around me. All the clever camera bags and pockets and stuff just get in the way. What more do we need than a camera, or two, and a lens or two?

What Camera Straps do you use? All my cameras have UpStrap-Pro bandoliers. They’re nylon slings that I wear crosswise and they sit just higher than my hand rests when I’m walking. You could probably make these with a quick trip to REI or MEC or some other hiking or climbing store but UpStrap-Pro.com has them for $20 or something. I’ve tried a lot of fancy clever straps and none of them work for me like a simple bandolier. And I’ll put the $50 I save toward something that really makes a difference to my photography, like printing my work.

Anything Else? Other than a cool scarf? No. Listen, when we first get into photography – I remember these days well, and I’ve bought more gear than many of you combined – we want to buy every little gadget. We’re under the mistaken impression that any of them really matter. Sure, some do. Most don’t. You know the kind of photography you do, and you’ll know you really need Thing X when you can’t do your work without it, or Thing Y no longer does it for you. The more gimmicks I tried – the fancy camera bags, the $100 straps, the more I felt like a photographer was meant to feel, and the more those damn things just got in my way or encouraged me to carry more crap than I needed and that too got in my way. You know what’ll really make you feel like a photographer? Making better photographs. If you’re already sold on that you can skip to the last paragraph.

I have a feeling that much of the crap sold to photographers doesn’t serve our photography so much as it serves our ego. Not that you need it, but this is my permission to not look like a pro photographer. You don’t need the biggest best glass, unless you really, really need it. I harp on the Canon 85/1.2L a lot, and I’m going to do it again. It’s ludicrously expensive. It’s heavy. It’s very slow. Most people don’t need one, and most people will make better photographs without one. But it looks cool. You will look awesome carrying it. I know I did. But I make better photographs with something lighter and faster. You probably don’t need 4 lenses. or the Pro-sized body and grip. Or the really cool-looking camera bag with 20 pockets and a hidden darkroom. Or whatever else is about to hit the market that screams “photographer!”

Most of us would make better images if we stopped worrying so much about our own image. If you want to impress us, show us your photographs, not your list of L lenses or your weird leather hipster camera straps. And we’d make better photographs if we spent more time pouring over the work of past masters, or painters, or other visual artists, and actually learning our craft, than pouring over the latest catalogue from StuffMart.

The most valuable things you can bring to your photography can never, ever, be bought at the camera store: curiosity, patience, the willingness to put in the time, to fail, to see light and lines and anticipate moments. The ability to tell a story, express an emotion, or tell the hard truth. We’ll make better photographs when we concentrate on that and worry less about the other stuff.

I knew this would turn all ranty and stuff. My comments apply, I think, across genres of photography, but are made specifically in consideration of my travel and street photography contexts. Clearly if you are making wildlife or landscape or wedding photographs, your needs will be different. The point, however, remains.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

March 22, 2016

The Great Bear Sea

I spent this weekend diving in the Great Bear Sea with friends, among them two people I’ve long admired – Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier. We dove several times among Steller Sea Lions and forests of white plumose anemone and purple urchins, spending our surface time talking about the state of things in the natural world and our desire to see it last for future generations. To be in the company of these incredible animals, beside people with such incredible talent, heart, and commitment, is humbling and inspiring and gives me glimpses into the direction of some of my future work. These natural places will not last forever, and our appetites for money, for fish, for oil, threaten them unless we learn to live in harmony with this world. More and more I believe that the single greatest humanitarian task of our generation is the conservation of the world on which we depend, and I wonder with great curiosity and anticipation where this is all taking me.

I’m posting a couple rough images below so I can share the wonder with you.

I’ve also recorded a new episode of Vision Is Better. Join me for Episode 35 as I discuss 3 of my favourite features and techniques in Lightroom.

Finally, I’ve also just posted the full list of opportunites to travel and learn with me in the next 12 months. There are limited spots in the Venice, Tuscany, and Rome Mentor Series Workshops, a new safari in Kenya next January, and – if you’re lucky – still one spot left for a one-week Mentor Series Workshop in Jodhpur, India, a year from now. You can find these on my Workshops page on the Craft & Vision site. All of these are extremely limited and by application only, but I’d love to travel with you, and the application’s not hard or long – just something to give me a sense of who you are and where you’re at as a photographer so I can create the best possible experience for you. Check those out here.

March 14, 2016

Vision-Driven Exposure: A Clarification

I wanted to follow up on my article about how I expose, to clarify a few things. If you’ve read that article, read on. If not, you might want to read it first.

To make a few things clear, my last post was not a dismissal of craft. Craft has its place. Excellence matters. But there’s this thing about people that hold to craft as though it is the end itself, the goal, and not merely a means to something more: they have a tough time moving on when there’s a better way. Digital photography has no different a goal than film photography did. The means to get there is, or can be, increasingly different. I cut my teeth on films like Tri-X and T-Max and Velvia and I’m pretty sure if you send my blood to the lab you’d find traces of developer and fixer still in there from the hours I spent in the darkroom in my basement. So when I suggest that I don’t use a light meter anymore, but instead get to my exposures through a different path, it’s not for ignorance of the old ways, it’s for choosing a path more appropriate to the new technology.

I don’t see any honour in clinging to your ability to use a light meter if there’s no reason to do so. You might have those reasons. But many of us no longer do. I understand the zone system. There are exceptional photographers who have never heard of it. They still make great photographs. And I know how to spot meter; I just don’t need to know how to do so in order to make the photographs I make. Nor do I see a reason to burden my students with it if their cameras don’t demand it. The goal is to make an exposure that is both excellent and expressive in it’s final form: the print. The goal, at least digitally, is the best digital negative. And when compromises are needed, to know enough to make those compromises well. A histogram is a different way of looking at the light and making a decision about how to best use it.

We’ll all make much better photographs if we love our photographs more than we love our tools.

Use the tool appropriate to your needs. If that’s a histogram, then understand it. Be comfortable with it. Make sure it doesn’t get in your way. One of the things I should have been more clear about in my first article is that this way of doing things wouldn’t have been possible while I was using DSLR cameras. The lack of in-viewfinder histograms and an ability to see my exposure in real time, would have taken me too far out of the moment. If you’re thinking I make a frame on my DLSR, chimp through to look at the histogram, then put the camera back to my eye, you’re dead wrong, and I was less-than-clear. Nothing is more important to me than staying in the moment. Not even a perfect exposure. If your camera lets you do both, great – mine does – but if it doesn’t, use the best tool for the job, and that’s probably still metering traditionally.

If you’re thinking I make a frame on my DLSR, chimp through to look at the histogram, then put the camera back to my eye, you’re dead wrong, and I was less-than-clear. Nothing is more important to me than staying in the moment.

There’s a danger with blogs to read one article as though it were the sum total of the author’s thoughts on a subject. No reader is going to read the entire archives to see if something is more fully expressed elsewhere. And no author is going to re-hash years of writing just to be sure he’s going to be perfectly understood. I’ve written often on the need for excellence in craft. You have to know how to expose a photograph. You have to understand the medium and the tools. But when new technology comes along, like mirrorless cameras with in-viewfinder histograms, then the way we get to that final photograph can change. New wine for new wineskins as another teacher once put it.

In the end I love my craft but it’s only a means to achieving a thing I love more – the photograph. Do that in whatever way allows you to create something that shows me the world in a new way, that makes my pulse quicken and sparks my imagination. Use a light meter or don’t. Use a point and shoot digital camera or a 4×5 field camera. No one cares how you got there when they’re experiencing depth and beauty in your work. We’ll all make much better photographs if we love our photographs more than we love our tools.

Share the Love, Share this Post

March 13, 2016

Vision-Driven Exposures

This is my confession. I never use a light meter. I don’t spot meter. In fact most of the time I don’t even know what metering mode I’m on. My life as a digital photographer became infinitely easier when I abandoned those, put my camera back to manual and simply began exposing for what’s important.

Whether you use a meter or not – and you’re more likely to do so if you’re using a DLSR without in-viewfinder live histograms – isn’t the point. The point is understanding how to make the photograph you want, and knowing how to use a histogram is – at least for the digital photographer – key to this. I’ll explain that in a moment, along with the explanation of how I expose my images, but first I want to talk more directly to why I am writing this.

Something of a religion has been made of histograms lately, and with it, like all religions, a growing list of dos and do nots. Don’t burn out your highlights. Don’t lose shadow in the details. And, like most religions, especially the weird culty ones, there is almost never an explanation of why this dictate is to be followed at all. Here, in point form, are the short notes:

Burned out highlights mean no detail in those highlights.

Blocked up shadows mean no details in those shadows.

This, we are led to believe, is bad. And so, because badness – one assumes – is to be avoided, we give our reasoned minds over to the Histogram, in the hopes that slavish obedience to It will save us from ourselves. Hail the Histogram.

But there’s a problem. Digital sensors can’t capture the full spectrum of light from darkest blacks to brightest whites in every scene. Which means there are scenes in which one must make a choice. Do I expose for the lights and – God help me – plunge the shadow details into oblivion, or do I choose the shadows and let the highlights disappear? And that’s the exact spot the beginners who struggle with this, get stuck. Needlessly stuck.

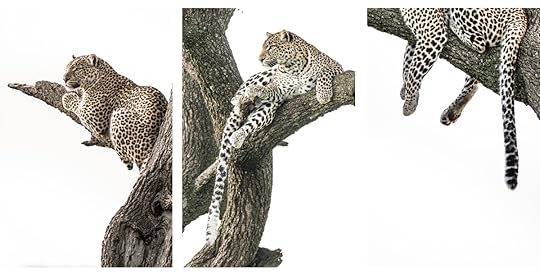

It’s OK to blow your highlights. Obliterate them if they are unnecessary. See the photographs of the leopard? The dynamic range was far too great to expose for both detailed shadows (the leopard) and detailed highlights (the sky). So i have a choice and here are the two important questions: what’s possible, and what’s important? To me the leopard was key. I could have made a silhouette and exposed for the sky but it was featureless and uninteresting. Or I could have exposed for the leopard and let that featureless sky, the one without any real detail, just blow out. So I looked at my histogram and pushed it until the shadows had plenty of detail and then looked at the highlight warnings (the blinks) to be sure the highlights I was losing were only in the sky and not on the leopard (there are some highlights in which you really want to keep detail.) It’s not about whether I lose highlight details. It’s about which highlight details I lose.

The leopard, silhouetted in front of the setting sun, has both blown highlights and plunged shadows.

It’s also OK to plunge your shadows. Shadows are good. Say it with me: Shadows are good. Shadows add mood. They help isolate or frame key elements. They create new lines and shapes. Remember details have visual mass – they pull the eye. They provide information, and if that information is unnecessary, it can reduce impact by being a distraction. We used to do this all the time when photographing with slide film – underexpose the frame to make colours punchier, to keep the lighter, more important elements correctly exposed, and to add drama. There is no sin in trading details in the shadows so you can make a stronger photograph. See the images below where I’ve intentionally allowed the shadows to go much darker and imagine how much less impact the photographs would have if I’d exposed for them instead.

My camera wanted to make this scene a boring mess. Exposing manually I kept dialing the exposure down until I got all the highlights back (nothing running off the right side of the histogram). This gave me the best file. Then I underexposed it further in Lightroom. This gave me the best final photograph.

The sun is burned out. It will always be burned out. There is no detail in the sun. But I kept underexposing until the detail and colour in the sky came back.

That’s why metering modes aren’t helpful to me. Put the camera on manual, look at the histogram and expose according to where you want the information and where you want the impact. My Fuji cameras allow me to see what the image will look like if I dial that aperture closed, it’ll show me the impact of shadows. And it’ll show the inverse when I open it up – which highlights I’m blowing.

There is a give and take in exposing a photograph. Understand what you want from the image. Ask yourself where you want the information and where you want the impact. Will that overexposed area help you achieve your vision or will it pull the eye unnecessarily? Will those dark shadows create a stronger composition or will they obscure things that are key to your intent. Now, having done that, make the best possible exposure. Use your histogram, make it your b*tch, as they say. Don’t let it tell you what to do. It is there to tell you only what’s possible with the scene, not what you must or must not do.

A few last bits. It helps to shoot in RAW format – you’ll have much more flexibility and data. Using lower ISOs will still give you cleaner files and more flexibility. Where you can, it’s still prudent to push the histogram to the right to get as much data as you can. Don’t rely on the LCD screen to show you exactly what the image is going to look like – LCDs are for generalities, the histogram is more precise. Understand how to read the histogram, keep an eye on your blinkies so you know which details you’re losing, and most of all, expose for what matters to you, not to me, not to the pundits, but you. This is about making great photographs, not perfect histograms.

Like anything I write, my way is not the only way, but it’s the one that works for me. Questions?

Share the Love, Share this Post

March 10, 2016

Italy Mentoring Workshops

It’s no secret I adore Italy, and teaching the craft I love in such an intoxicating place is high on my list of things I am grateful for. Last year I offered one chance to join me in Italy, this year I’m offering 3. Join me for a week in one of three great Italian cities this fall.

Each of these weeks is an intensive, 4-person workshop designed to explore your creative process, hone your photographic craft and create a cohesive body of work. You will explore, often on your own, the streets of these astonishing cities, share meals together, engage in honest critiques of your ongoing work, and be challenged to push yourself by someone who cares deeply about your art and won’t take no for an answer. And at the end of the week you’ll present a 12-image body of work.

What will this week really be like? Late nights talking about life and art and craft over Italian wine and great food. Hours walking in the changing lights on Italian cobbled streets with your camera, looking for your muse. Coffee with me while you discuss your work and laugh, or cry, about challenges and victories of creative work passionately pursued. People usually do a little of both. Because if you aren’t willing to both laugh and cry about it, it’s probably not worth going all that way for.

Each week is USD$4900 and includes meals and accommodations. You’ll find more information, and the online application, on the workshop page.

This will be an intense week and is by application only.

There are 12 spaces available (a maximum of 4 each week), so get your application in as soon as you know one of these workshops is a possibility for you. The online application form will ask you to write something brief about why you want to join me in Italy, and it’ll ask you to submit a portfolio of 10-12 images (JPG, 1200px on the long side) so I can get a sense of who you are and where you’re at.

“Joining David on his Venice workshop goes down as one of the most pivotal experiences of my photography career and it’s not because of his intimate knowledge of this beautiful city. Rather, it was because of the special bond that formed between the mentor and the student during an intensive week of pushing your boundaries and your creative abilities. It’s in the particular, personalized way that David challenges you to grow that makes this investment pay back with dividends.”Brian Matiash

Share the Love, Share this Post.