David duChemin's Blog, page 5

April 17, 2017

It’s All Subjective

These were the questions I was asked last week and I think they open an interesting conversation. Here’s my take on it:

Yes. A photograph needs a subject. It needs something about which to be. In the same way a story or a poem or a song needs to be about something, so too does a photograph. But remember that subject need not be a tree or a person or a specific element in the photograph. That subject might be a mood or an emotion or an idea; it might be really abstract, but I can’t think of a photograph that’s not about something.

Where we get bogged down a little is in the confusion created when we assume that the elements in the photograph are the same thing as the subject of the photograph. Sometimes they are, but it’s not always so simple. An example: You’re on the streets of New York and you make a photograph of a yellow cab, because no one has ever done that. It’s a literal take on a New York Taxi. A photograph of a taxi. Note the emphasis. But is it a photograph about the taxi? It might be. In which case the subject of the photograph and the way you express that subject are the same. Move along, nothing to see here. But if you want the subject to be a little more specific, perhaps an idea or a feeling, like how the city is always in motion, a whirl of colour and movement, then that is your subject and the photograph may or may not need a taxi in it. Maybe the best way to express that is with a blue car, or several cars of different colours all blurred together.

Another example. You’re photographing a landscape. You were drawn to the scene because the light and the mist was breathtaking. As you photograph you move the camera around. Sometimes there’s a tree in the shot, sometimes not. Sometimes there are three trees. Is the tree the point of the photograph? No. Do you need it in the shot? Maybe yes, and maybe no. The tree is one element, but not the subject. The subject is the light and the mist, even perhaps the mood, the mystery, created by the way the light and the mist interact. The big challenge has always been to find the best expression of that subject.

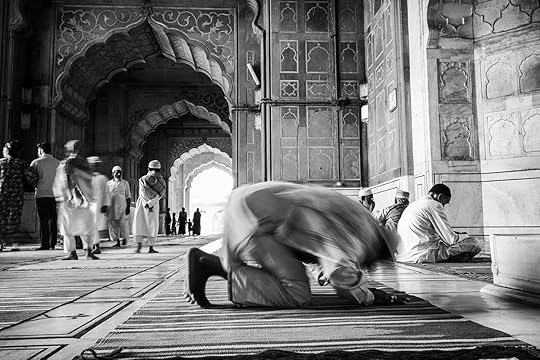

One last example. A quick one. Like the image at the top of this post – what is the subject in this image above? Is it the specific man you see there? No, it’s devotion. Faith. Prayer. The same subject is expressed in the next two images below. Same subject, different expressions of that subject. Knowing that my subject was the idea of devotion and not, for example, the specific person, helps lead me to different creative options, like knowing that not only do I not need to see the details of the faces really clearly, but that it’s the shape of the silhouettes, or the movement in the gesture, that more powerfully communicates the idea.

This is a favourite sermon of mine, because I think understanding it helps make stronger photographs. Even though the questions are a little more sub-conscious most of the time now that I’ve been doing this for 30 years, asking myself these two questions remains a necessary part of my creative process. Try asking these two questions for every photograph you make:

What is this photograph about?

How can I give that subject its strongest expression in the photograph?

If these two questions are helpful to you, here are another two questions you might want to consider.

And if you want more conversations like this, about what makes stronger photographs, beyond the buttons and the dials and usually technical stuff, consider reading one of my books. My latest book, The Soul of the Camera, The Photographer’s Place in Picture-Making, is available now for pre-order and should be in your hands around the middle of June.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

April 10, 2017

Two Big Questions

Walking through Jodhpur with a friend last week he asked me a series of questions about the way I think when I photograph, specifically: how do I prioritize and make the decisions that I do? Do you choose aperture first, or shutter? Do you reach for a wider lens or a tighter? Do you back up, get close? So many decisions, how do you approach it? Here are a couple thoughts and then the two guiding questions I’ve recognized are always bouncing around my brain when I make photographs. The photographs I make depend heavily on how I answer these questions

First, it’s important to remember that how I, or anyone that’s been doing this for half a lifetime or more, think about things will be different than for those a little newer to the game. After years so much of the thoughts become sub-conscious, the program running in the background. Focusing and exposing and some of the mechanics is no longer the main concern, only because it just kind of happens in your hands if you’re paying attention even a little. So on that account, it’s a little easier. There’s less to think consciously about. The benefits of this, and so-called muscle memory, are many, and are the reason I wrote this article, The Best Camera.

The two big questions always running through my head, from which many smaller questions come, are these: What do I want to say? And, How can I best say that?

What do I want to say? I walk around a corner in India, Italy, wherever, and see something that makes me put my camera quickly to my eye. But why?What was it that lit me up inside? A beam of light? The dust? The mood? The action of the thing? The elegance? The grit? Let’s say it’s the woman sweeping in the image at the top of this post (rss readers can find it here): for me it was two primary things: the shape of the woman sweeping and the dust that she was kicking up. What I wanted to say was not a complicated thing, it had no agenda, simply: look at that. Look at the way the light catches the dust, look at the relationship between the woman sweeping and the woman just walking by. Now I ask the more practical question: how can I give that subject its strongest expression, or…

How can I best say that? Or, to put it another way, what do I want the photograph to look like? The latter question is more about possibilities than finding one specific answer. In the case of the woman I was photographing I knew it had to be backlit because moving around her would change the way the light hit the dust relative to my camera and I’d lose the magic of that. I’d also lose the silhouettes. I knew I needed to dramatically underexpose the scene, or expose for the highlights, and so I cranked my aperture down (to f/20) because I was already at a shutter speed that would work (1/125) and there was a chance I might get a pinpoint of sun poking through the overhead awnings, and y’all know I’ve got a weakness for sun flare and starbursts. The ISO was 800 which is my starting place on mornings like this and delivers perfectly good images. But had I wanted to say something about the motion of the scene I would have cranked the ISO down, and opened the shutter to give me something closer to 1/15 or 1/8 to make the motion part of the image.

Vision-Priority Mode. I’ve told you before I shoot entirely on manual these days. I’m faster this way. But it’s preference not dogma. Use whatever mode you need to to make photographs quickly and without too much messing around. The most important thing is that you remain in the moment and give your attention to answering the above two questions, not encumbering the process with a third question: ok, now which dials and buttons do I use to get there. You should know that. It should be second-nature. The camera can’t do it for you. What mode should you use? The one that you can use fastest, that allows you to make the images you want to make, that say what you want to say in the strongest possible ways.

When we start all we want is to answer simple (but vexing) questions: how do I expose this damn thing, and how do I get it focus. Once you can do that there are better questions. Try it next time you’re out. If “what do I want to say?” is too large a question, try: “what specifically about this scene am I reacting to?” Find a way to express that. Is it about colour? Light? Shape? Is it action that requires a different POV (point of view) or a relationship between foreground and background that requires a different lens. With time you’ll get better – faster – at finding these starting points. But they are only that: starting points. Rarely is my first try successful. I put the camera to my eye and play, try, experiment, looking at the results in the viewfinder as I shoot them (another advantage of mirrorless cameras and their electronic viewfinders), and then tweaking my approach. But all the while I’m asking myself, reminding myself, two of my most important questions are: what do I want to say, to point at, and how do I want the image to look, what will give that subject its best expression. We have an insane number of ways of accomplishing things with a camera.

Like this kind of approach? Around June 15, my new book, The Soul of the Camera, The Photographer’s Place in Picture-Making, will be released. You can pre-order it now on Amazon, or get your hands on a signed edition here while they last.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

April 6, 2017

The Soul of the Camera [Signature Edition]

On or around June 15, my next book, Soul of the Camera, The Photographer’s Place in Picture-Making, will be released. I have the first copy here beside me and I haven’t been this proud of something I’ve written in a long time. One of the questions I always get is a hard one for me: how can I get a signed copy? It’s hard because short of flying to my home on Vancouver Island with a copy for me to sign for you, there’s no easy way for me to do this. I can’t beat Amazon for price or shipping, never mind the time it takes me to sign a bunch of books then ship them. But I’m really proud of this book and I want to give at least some of you a chance to get a signed copy if you want one, and still get value for the price you pay, because I have a tough time believing my signature alone is worth much. In fact the book might be worth more in the long term if you just leave it blank, but that’s up to you.

So I’ve put aside 100 copies (or I will, as soon as they arrive) and I’m going to put 2 signed prints (8×5) inside the book, sign and number the books themselves, and include a PDF copy of the book, which I will email to you on June 15, so you’ve got it to read on the bus or plane without lugging this beautiful hardback everywhere you go, and I’ll include shipping.

The cost of the Signature Edition is USD$100, shipping included. There’s only 100, so if you want one, this is that chance.

Download the Sample Chapters

Want to take a look at the book? Here’s a download link to a couple sample chapters for the book. Even if you decide to just pre-order the book on Amazon (it’s $24.25), I’d love you to take a look at what’s coming, and to share my excitement.

Get Your Signature Edition Now

Click this link and it’ll take you to the right shelf on Craft & Vision Store. Once you purchase you’ll get a confirmation email almost immediately and we’ll sign and send the book as soon as we can, but that’ll be close to June 15. At the same time (June 15) we’ll send the PDF copy of the book, ready to be loaded on your laptop, iPhone, or tablet.

Here’s What Others Have Said

“The Soul of The Camera inspires the artist through compelling writing, impactful imagery, and reference-friendly bits of wisdom placed throughout the book. David is highly quotable throughout, but he is also highly thought-provoking. Loved this book.” ~ Tamara Lackey

“David nails what is often elusive – the ‘certain something’ that some images have that others simply lack – not only through his images but through his understanding of photographic, artistic and personal craft. This book is an intimate look into the workings of someone who puts tremendous soul into his work, but it is also a guidebook, written ever-so-poetically, about the pivotal role the artist plays in what an image says and does to the person viewing it. I recommend anyone, even outside of traditional artistic crafts, read this book to put the soul back into your work and life.” ~ Brooke Shaden

“David duChemin understands an important truth about photography; as photographers, what shapes our craft is how we see the world as humans, not the equipment we use or the situations we find ourselves in. The soul of the camera resides within our humanity, and duChemin does an amazing job of communicating how to access it.” ~ Paul Nicklen, National Geographic Photographer

“If you want to get in touch with the inner game of photography, you can do no better than to read The Soul of the Camera. David duChemin, photography’s Thomas Moore, puts soul into everything he does; never more so than in this book.” ~ John Paul Caponigro

April 5, 2017

The Best Camera?

When, a couple years ago, Chase Jarvis popularized the idea that the best camera was the one you had with you, I was totally on board. I still am; there is much truth in the idea. But if someone is asking the question, “which camera should I get?” it’s less helpful. And this is a question I hear too often to ignore. So without taking away from the truth of the one idea, I want to propose that for this discussion the best camera is the one that gets out of the way as quickly as possible.

“The sooner photography is about photographs and not camera and settings, the better.”

Muscle memory is incredibly important for practitioners of this craft. Our brain is constantly making shifts from one side to the other as we consult both the technical and creative hemispheres. The less attention we have to give to the one the more attention we can give to the other and the less jumping back and forth we have to do. That’s where muscle memory comes in. I will make better photographs if I can put my camera to my eye and never take it away, never have to consciously think, “Oh man, I need to dial my aperture down, now which dial is that and which way do I turn it? Nope, that’s the ISO. Sh*t, that one was my white balance…oh, forget it, the moment’s passed. Maybe next time” This is probably the biggest reason I use the cameras I do. The Fuji X system feels right in my hands in the way a Nikon or Leica does for others. I know where everything vital is, and because of years using analog cameras with the same aperture rings and shutter speed dials, I can photograph without having to be conscious about what my hands are doing, I can stay in the moment. I can put my energy to creative concerns: my composition, choice of moments, point of view, and the energy needed just to be present and receptive. Get the camera that lets you do that, whatever the brand.

For most photographers, especially those just starting out, every current camera out there is capable of doing what it is told and rendering a sharp, well-exposed photograph. The question is how easily can you tell it what to do? How much effort and second-guessing do you need to go through to make that happen? Photographs are made not by cameras but with them; they are made by photographers. So go to the camera store and get the camera into your hands, get a feel for the dials and the buttons. Some cameras work better in larger hands. Some will have button and dial placements that feel intuitive to you and others will not. Get the one that feels right.

And if you’ve already got your cameras and made your choice, then get to muscle memory as fast as you can. Spend the time memorizing the important stuff, your aperture, shutter, ISO, and anything else you use often as you photograph. Make it second nature. If you can do it without thinking, in the heat of a passing moment, or changing light, you can pay attention to those latter things, not the former. The sooner photography is about photographs and not camera and settings, the better.

“Get the one that feels right.”

There are other considerations when choosing a camera. Of course there are. But see, if you already know you need certain things, like a specific megapixel size, or the ability to do kick-ass night photography, then you aren’t just starting out, and you should know what your needs are. You should also know that if you can’t use even the best, sharpest, fastest, low-lightest camera intuitively, and if it doesn’t get out of the way quickly for you and just let you do your thing, it’s not the best camera for you. And if you don’t know those things, if you don’t have a list of must-have features, then you don’t need them. Like the idea that the best camera is the one you have with you, it doesn’t answer every question or serve every circumstance. But while the geeks are arguing about this stuff on the forum you’ll be out making photographs with a camera that lets you focus on the things that are ultimately truly responsible for making photographs – being present, seeing in new ways, making creative decisions about interpreting your scene and finding the best expression of the thing that has captured your imagination. Don’t let your choice of camera, no matter how big, shiny, or well-branded, get in the way of that.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

April 3, 2017

More Postcards from Jodhpur

I’m writing this in turbulence 40,000 ft over Afghanistan on the way home from India, so it’s hardly a postcard from Jodhpur but then I usually send my mother her postcards when I get home too, so that makes you family. I’ve just wrapped up 2 weeks in Rajasthan, and now making a run for home to get my hands on the first copy of The Soul of the Camera and start packing bags for back-to-back dive trips to Bahamas and Mexico to continue my underwater work.

If the idea of spending a week with me in India intrigues you I will soon be announcing two one-week Mentor Series Workshops in Varanasi in March 2018. I’ll be going to Varanasi early to work on a video project and to photograph Holi, then I’ll be working with 5 students for each week-long workshop. If you think you want to be one of them make sure your name is on the list to be notified when spots open up.

Here’s a first glimpse at the images from last week.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

March 25, 2017

Postcards from Jodhpur

After a busy, and increasingly hot, week in Jodhpur with my first of two Mentor Series Workshops here in Rajasthan, one group of students is now leaving with beautiful bodies of work and another has just arrived. We spend our early mornings walking the streets, padding our shoeless way through temples, sitting with our favourite chai wallas, and following unexpected invitations and opportunities. It’s a great city for that, and every street and alley seems to be hemmed in by the bluest walls. So it seems almost a shame to photograph this place in black and white, but the thing is when you go deep you realize this city isn’t about blue. It’s so much more than that. It’s hard workers and street chaos, stolen moments between friends, the endless ringing of temple bells and honking of rickshaw horns. Anyways, I know it’s been a while so I wanted to check in and say hello, and send some postcards. I’ll check in again in a week when this next workshop is over and we’re homeward bound.

If you like the idea of spending a week with me in India, we’re planning to launch 2 one-week Mentor Series Workshops in Varanasi next year, roughly March 04-10 and 11 to 17. I will only be taking 5 students for each, several of the spots now already spoken for by alumni. Just my way of letting you know now is the time to think about it, because when we announce it there won’t be a lot of time to get an application in. Varanasi is an exciting, raw place, and I can’t wait to be walking up and down the ghats again. If you want to be sure you here about this, make sure you’re on my workshop newsletter (Click here). We’ll only email you when a workshop opportunity comes up, and there aren’t many. We won’t spam you.

One last thing: we’re giving away a Fuji XT-2, 18-55mm lens, Fuji-X Domke satchel, and a signed copy of my next book, The Soul of the Camera. It’s over on March 28, so get your name in now if you haven’t already. And if you want more chances to win, there’s a way to do that by sharing with others that might benefit. Good luck! (Click here to get your name in)

Share this Post, Share the Love.

March 5, 2017

You Can’t Zoom With Your Feet.

I get nervous when I hear teachers spouting platitudes, especially when they are expressed in the imperative. Do this. Do that. And I get really nervous when I hear my students repeating them. Platitudes are easy to remember. They simplify things. But they do not, generally speaking, teach. They do not change the way we think, only the way we act. And that’s a problem because prescriptively changing our behaviour without thinking leads to the same kind of thoughtless and unintentional behaviour that the platitude was initially spouted to prevent.

Let me give you an example that’s been chafing me in all the wrong places:

Zoom with your feet (hereafter referred to as ZWYF because that makes it sound more sinister).

On first glance ZWYF sounds great. The kernel of truth that got wrapped up in this silly edict is this: for the love of St. Ansel, move your damn feet. Get close physically! Not bad advice much of the time. Less applicable however when you’re photographing lions. Personal safety aside, there’s a downside that’s worse than getting horribly maimed: your photographs might not get any better. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a HUGE fan of getting close. But, with apologies to Robert Capa, getting close is not a magical “make it better” formula.

You see, ZWYF tries to solve one problem, namely the need for people who only shoot with prime lenses to feel smug, but it introduces another. Moving your position relative to a subject is not remotely the same thing as changing your focal length. Focal lengths behave differently and, here’s the important part, they change the relationships of elements to each other in a way that is different than moving the camera itself.

“Understanding this will make you a better photographer than just blindly following a platitude, which is really just a rule dressed in drag, disguised as wisdom.”

In other words, you can’t ZWYF. It’s not possible. You can zoom. You can move your feet. They aren’t the same thing and they don’t accomplish the same visual results as each other. When I photograph the only thing that matters to me is making the photograph the way it’s begging me to be made. And I don’t know that until I move around, usually dodging and weaving, in and out, like a punch-drunk (just drunk?) boxer. I am constantly moving my position as well as tweaking my focal length, watching as I do that how the elements appear to move around relative to each other and to the frame itself. Sometimes I move closer but pull my focal length much wider, increasing the size of the foreground element. Sometimes I back up but rack the lens out to a longer focal length, pushing the foreground and background closer while also keeping it all in frame. I move. I zoom. It’s a dance and there’s a lot of improvising.

Understanding this will make you a better photographer than just blindly following a platitude, which is really just a rule dressed in drag, disguised as wisdom. And y’all know how I feel about rules. This is one of the reasons I like zoom lenses so much. I know, primes are really sexy. They’re pure, or so I’m told. And I know people who love, and make astonishing work with, their prime lenses. They embrace that constraint. But it’s really important to me to control the elements in my frame and the way they relate -spatially and conceptually – to each other. Follow the rule or don’t. Use primes or zooms. The only thing that matters to me is making stronger, more intentional photographs, and I’ll do whatever I need to with my feet, or my zoom lens, to do that.

Ansel Adams Would Totally Share This Post.

February 27, 2017

High Ground: A Rant

This one might be more for me than for you, but I had to get it out and this is where I do that kind of thing. I’m hoping there’s someone out there that needs to hear it, someone for whom this will bring some creative freedom.

Remember being a kid and climbing to the top of whatever we could find, chanting, “I’m the king of the castle, and you’re the dirty rascal”? Maybe that was just a Canadian thing. As we got older those of us that weren’t by nature sociopaths realized all we were doing was isolating ourselves and the game was no fun when we were alone at the top.

It is very easy to strand ourselves on the high ground. In our search for significance – or our hopes that our images are significant – it’s very easy to find that high ground in any place but in our photographs themselves.

Nothing is like film, they say. “Digital” is ruining photography, they whisper. I only use prime lenses, they brag. I will never use anything but a Leica, and I never crop my images. I don’t “do Photoshop.” Real photographers only use manual mode.

Bullsh*t.

It’s true. Film is beautiful. It’s unique as its own thing. And yes, digital technology gives way to certain temptations for artists and changes in the art itself. Prime lenses are beautiful. So are Leica cameras. And if you work better in manual mode, and don’t work on images in the darkroom, digital or analog, then great.

But when those things – and you can pick your favourite from a long list of potential badges of honour – become a substitute for the hard and humbling work of making compelling photographs – then you can keep your high ground. The rest of us will be slogging away in the dirt, trying to grow, to challenge ourselves, to hone our craft, and to make something that is alive, something that speaks for itself and that transcends questions about cameras and brands and which f*cking lens you used.

When your badge of honour is the brand of camera you use, the weird constraint you placed on yourself, or how hard you think you work to make your photographs, and it’s not the experience of the image itself, then it’s no wonder you feel a little bit alone up there. Because photography might be all about you, to you, but the rest of the world is looking for something more: for life, for truth, (or a break from the truth), for something real, vulnerable, sensual. They are looking for soul. For depth. For beauty and a distraction. They want the muse to unexpectedly push them up against the wall and kiss them hard.

“They are looking for soul. For depth. For beauty and a distraction. They want the muse to unexpectedly push them up against the wall and kiss them hard.”

And – listen – when the muse so seduces them, they aren’t for a moment asking themselves who made her dress, or how it was made and from what. And your bragging about such trivial things, trying to catch my attention with your not-so-subtle fake cough about film and lenses and whatever bullshit you think is important to you, over there in the corner – you’re just wrecking a beautiful moment. And if your muse is trying to get your attention, well, you’re probably going to miss that, too.

Photographers, I have this sneaky feeling some of us have forgotten something fundamental about the experience of art and wonder and the transcendence that’s possible with what we make: it’s not about us. It can be about something so much more. The muse, for her part, doesn’t give a shit about your gear or your pretense. She cares only for your vision and your willingness to give expression to it. And that’s the stuff that will become inspired and inspiring. Let her do her thing.

“Just be sure of this one thing: that you love the muse and what you create together more than the ever-changing tools you happen to use to create. “

And more to the point – for the rest of you, for those of us who just want to do our work and wonder if we’re missing something by not using the right gear, the right brand, the trendy processing, the old film camera, whatever: you aren’t. And if you are – if film or primes or pinhole cameras or some other precious thing suddenly becomes important to what you’re doing – you’ll know. And you’ll embrace it, struggle with it, use it for what they bring to your process, and you’ll make the same mix of awkward sketch images and beautiful master prints. And the success – or the failure of those – will not ultimately be credited to that gear, but to the dance between you and the muse that has always made the kind of art that opens eyes and hearts.

Just be sure of this one thing: that you love the muse and what you create together more than the ever-changing tools you happen to use to create. The tools matter, they are necessary, but they aren’t where we put our hearts. That beautiful, lofty, messy place is for the muse, and the dance, and the art alone.

Share this Post, Share the Love

February 22, 2017

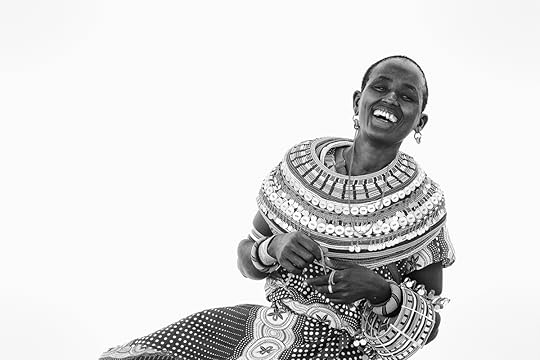

More Than Smiles

For years I chased smiles. I still do. I love a great laugh for the spark and openness it brings to a subject. But laughter and smiles, universal as they are, do not tell the whole story or express the full emotional gamut of the human race (riddling, perplexed, labrynthical soul, as John Donne so well expressed it.) I use laughter often to get to those other expressions of personality and soul. People come to the camera often quite nervous, unsure of what to do, and they hold back. They lock some key part of them behind a steely gaze or an awkward pose. We all do. Look at all those selfies out there – so many of them a pose, a mask. Pictures of ourselves, but not about ourselves. No revelation. No vulnerability. But there are many smiles. I wonder if there’s anything so good in the world as a smile to hide and conceal.

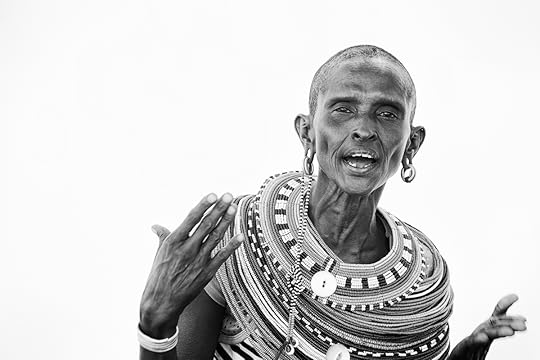

This is one of the reasons I’ve been working on my On White series the way I have over the last few years in Kenya. I often present a couple images of the same person side by side, one with genuine laughter and the other without, with some other expression – worry, concern, thoughtfulness, strength. To get this range of emotion is simple but not easy.

I’ve had a lot of people ask me how I do my portrait work in Kenya and it’s simple, if not easy. I use a couple collapsible white scrims, 5ft x 5ft, I think, with a diffusion panel on each. One for backdrop, the other to soften the light. And then I stand or sit with my subject, my translator close at my side and we just ask them to tell us their story. We ask about their kids, their lives, their challenges. Once in a while I ask them to stop what they’re saying and look at me. Sometimes I ask them to smile. Sometimes we ask them to laugh, which of course is an absurd request. You get forced smiles and insincere laughter. But you know what happens then? They see the ruse for what it is. They see how silly it is. And they smile. They laugh. Something genuine comes to the surface. That’s all I’m after. I know they’ll go home talking about this lunatic mzungu (swahili for stranger, white man) and how he’s obviously not a very good photographer because he took a hundred photographs and 10 minutes of their time. It’s a win/win.

What I’m really after is to show the humanity behind the stereotype. These women, and I occasionally photograph the men too, mostly the elders, are traditional nomads. Many of them are dressed heavily in beads and have large expanded earlobes from a lifetime of heavy piercings. They lead a hard life in a hard place. But what makes them human is the same as what makes us human, and any way that I can move people to empathy and compassion is better than moving them to pity, because it would be very easy to show these people, the poorest of the poor, many of them, with dirt and flies and all the various stereotypes that we bring to our notions of poverty. This isn’t about that. It’s about who they are, not merely the context in which they live, which is why I do what I can to show them without that context on front of the white. I want my photographs to be about them, not merely of them. And that requires more than the easy visual cues about poverty. But I also want not to romanticize the poverty, and that requires more than just smiles.

Share this Post, Share the Love.

February 20, 2017

Returning Home, Returning to Soul.

As always, I’m pretty sure I needed Kenya vastly more than it needed me, though I hope I served it in some way over the month I was there. Before leaving I felt like something was missing, like this digital ecosystem I’ve been so attached to was not only no longer fulfilling, but was, in fact, beginning to gnaw holes in my soul. And then I turned it all off a while, hopped a series of planes and walked out of the Nairobi airport into the warm evening air and felt like I was taking the deepest breaths I’d drawn in ages.

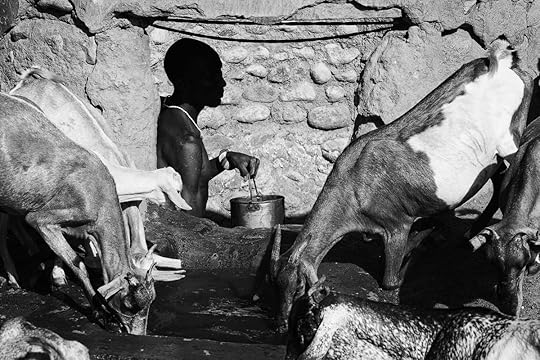

I spent the next couple weeks on safari, with friends and my girl and all the amazing creatures that make the Maasai Mara their home: elephants, lions, leopards, hippos, giraffe, zebra, and birds of a million colours. And then the woman I love hopped a plane home, replaced by my best friend, manager, and producer, Corwin, and we drove north for our fourth assignment with the Boma Project among the nomadic pastoralists of the arid lands south of the Ethiopia border and west of the Somalian. Somewhere in all the hard work I re-discovered my joy in making photographs, a joy that’s been hard to find lately. And I began to forget all about the pull of social media and email and the banal (but usually necessary) details that fill my days when I’m home. That forgetfulness happens when I start photographing places and people I love, when I’m doing something that feels important, vital, or urgent, when I’m making photographs I love so much that it doesn’t occur to me to wonder if others will to. It happens when what I’m doing is so important to me that I feel crushing heartbreak when I think about the possibility of failure. Makes me wonder how much stronger our work would be if that were our north star: to make work that risks heartbreak or the feeling that our souls would go hungry if we didn’t do it.

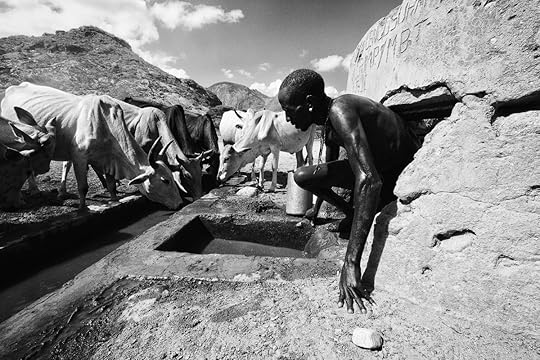

My goal this year is a return to soul, to push myself harder to experience deeper things and find new ways to express the experience, wonder, and hunger, in my photographs. It was writing my next book, The Soul of the Camera, that started to re-ignite this in me, this spark I once felt much more often, and pursued with greater desperation, as though it were life itself, which of course it is. This trip was a good start, surrounded as I was by people of such elegance, such dignity and strength. Here are a few of the images I came home with, pulled from the thousands I’m now editing.

You’ll notice an emphasis on water here. Significant parts of Northern Kenya are suffering a serious drought. President Uhuru Kenyatta has declared a national emergency. Herders are taking their herds and flocks to satellite camps hundreds of kilometers away, leaving families on their own, while the women walk several kilometers a day to get water at boreholes. Wells are drying up, one of them right in front of my eyes as men pulled the last of it up with buckets before moving on to find more.

Share this Post. Share the Love.