J.D. Porter's Blog, page 6

October 21, 2021

Herding Dogs: Hard-working, Intelligent Canines

One of the most popular shows on television these days is Kevin Costner’s modern-day cowboy saga, Yellowstone. I watched the first three seasons and will probably watch season four when it comes out from behind its “paywall”. But not everyone is a fan. My wife, for example, watched about twenty-minutes of the first episode before she gave up on it with the declaration, “There is not one character on this show that I admire.” She was right, of course. But I’ll probably keep watching anyway—even though it is not a program that would garner much approval from my Sunday school class.

Another criticism I’ve heard about the show is that there are no dogs on the Yellowstone Ranch. How can you have a working cattle ranch with cowboys, chuckwagons, and livestock but no dogs—no dog to sit on the porch with patriarch John Dutton as he sips his whiskey in the evening, no dog in the horse barn or cattle paddock. In fact, the only dogs I recall seeing were used by cattle rustlers who were stealing some cattle from the Yellowstone Ranch. The scene only lasted a few minutes, but it made an impression on me because the modern-day rustlers used herding dogs to move the cattle quickly and efficiently into a trailer.

As a zookeeper, early in my career, I often had to herd livestock into pens, crates, and trailers. It is not easy when they don’t want to go. That is why I have such admiration for the almost supernatural ability of herding dogs.

My only experience with a herding dog was with Bexley, our seventy-pound mutt that had herding instincts. When we picked her up from the animal shelter nearly twenty years ago she was a tiny, black ball of fur. Her lineage was unknown, but the shelter had listed her as a “terrier mix”. I don’t know what kind of terrier they thought she was, but she grew into a black and white version of Old English Sheepdog—a breed that was developed to help drive cattle and sheep to market. Maybe that’s why, as she grew older, Bexley had a tendency to bump the backs of our legs and nip at our heels as we moved about the house and yard.

Herding dogs were carved out of the American Kennel Club’s (AKC) Working Group in 1983. They were breeds that share the instinctive ability to control the movement of other animals. Herding dogs, which include shepherds, collies, and cattle dogs, were developed to gather, herd and protect livestock.

One of the most popular breeds of herding dog is the border collie, a beautiful, medium sized, black and white dog that was originally developed on the border of Scotland and England—hence the name. Dog experts widely agree that border collies are intelligent workaholics. They are capable of learning a remarkable number of words and commands, and they are happiest when they are put to work every day. When seen working at shows and herding trials, most people are astonished by their ability to herd sheep into a small pen, guided only by hand signals and whistles from their owners. Border collies are known for staring intensely at members of the flock to intimidate them—a tactic known as using “the eye”.

Another sheep herding dog is the Australian shepherd, or Aussie, a medium-sized worker that also has a keen, penetrating gaze. According to the United States Australian Shepherd Association, there are many theories as to the origin of the Australian shepherd but, despite its name, the breed as we know it today was developed in the United States. The Australian shepherd was given its name because of their association with the Basque sheepherders who came to the United States from Australia in the 1800’s. The Aussie rose rapidly in popularity with the boom of western riding after World War II, becoming known to the general public through appearances in rodeos, horse shows, movies, and television. Their inherent versatility and trainability made them useful on farms and ranches where American stockmen continued the development of the breed, maintaining their keen intelligence, strong herding instinct and eye-catching appearance.

Another popular herding dog is the Australian Cattle Dog (ACD). Also called blue heeler or Queensland heeler. This dog actually contains the bloodlines of a variety of other breeds including collies, kelpies, dalmatians, and even Australia’s famous wild dog, the Dingo. The result is a strong compact, symmetrically built working dog that conveys great agility, strength, and endurance. As the name implies, the dog’s prime function, and one for which it has no peer, is the control and movement of cattle. The breed is said to be “wary of strangers” which, according to one blogger, means that the odds are your heeler has already met everyone it wants to know. After that they may chase off strangers—even ones that are your new friends.

The use of dogs for herding even extends to the high-Arctic. I recently watched a program about reindeer on the PBS show Europe’s New Wild. Modern reindeer herders use technology such as GPS systems and snow machines but they also, it appears, use a dog called the Lapponian herder—a breed that was developed in Finland specifically to herd reindeer.

According to the AKC, the herding instinct in these breeds is so strong that they have been known to gently herd their owners, especially the children of the family. They are alert, courageous, and trustworthy with an implicit devotion to duty. But to be sane, they need to run for hours and use their considerable intelligence to outwit troublesome sheep, not sit inside a house all day while their owner is at work. In her 2002 book The Other End of the Leash, dog behavior expert Patricia McConnell bemoans the public’s interest in having working and herding dogs as pets. Border collies, for example, may be an ideal size and have beautiful coloring, but McConnell suggests that they are “as ill-suited to most households as mountain goats”. Experts recommend that herding dog owners participate with their dog in some sort of work, sport, or regular exercise to keep them mentally and physically fit.

Although our dog Bexley somehow had these herding instincts hard-wired into her makeup, she had little else in common with these pure-bred herding dogs. Bexley died a few years ago, but I don’t recall her being a particularly agile or versatile workaholic. If she had a penetrating gaze, it was well hidden by the mop of black fur that covered her eyes between haircuts. And she definitely missed out on the intelligence genes. In fact, the folks who ran the kennel where we regularly boarded her dubbed Bexley a “clown in a dog suit”. As lovable as she was, Bexley wasn’t going to outsmart anybody—even a herd of sheep.

September 28, 2021

The Right to Roam

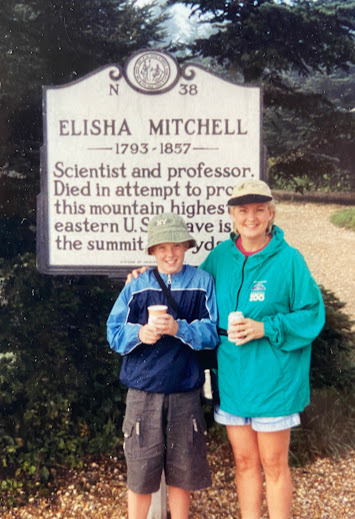

In the Cattail Creek community outside Burnsville, North Carolina it was known as “the Mt. Mitchell Hike”. My wife Karen and I did it twice. It was a four-hour trek from the top of Mt. Mitchell, the highest point east of the Mississippi at 6,684 feet, down the Northwest side of the mountain to my Mom and Dad’s cabin on Deep Gap Road. The trail—and I use that term loosely—meandered down steep grades and switchbacks with a drop in elevation of about two thousand feet. There were no signs to point the way, so we needed a guide.

The first couple of hours walking from the Mt. Mitchell peak took us along the ridge of the Black Mountains, through small valleys and up to new peaks. We passed over Big Tom, Balsam Cone, Cattail Peak and Potato Hill. We began our two-thousand-foot descent at a place called Deep Gap and were soon out of the State Park and onto private property. I never saw any signs, but I am pretty sure we were trespassing for the rest of our hike. We never met any resistance from landowners, but if we had been in parts of Western Europe we would have been protected by something called the Right to Roam.

In countries like Scotland, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, the freedom to roam the countryside has been written into specific laws. The Right to Roam is considered so important to the health and mental well-being of these nation, that it supersedes that peculiarly American concept of private property—a concept that makes us want to exclude.

In Europe, the right to enter and walk through a person’s property does not include any economic activities like hunting or logging nor does it allow any disruptive activities like building fires and driving off-road vehicles. Instead, every person has a right to explore these vast open spaces; to sleep there; to kayak, swim, and climb; and to ride horses and bicycles. Roamers are even accommodated by landowners with self-closing rambler gates, kissing gates, and climbable stile gates which allow people to pass through but not livestock.

This right, however, is contingent on adhering to a strict set of responsibilities. These are simple, basic rules on how to behave in the countryside in such a way that you neither interrupt the function of a working, agricultural landscape, nor damage the ecology of where you roam. When children grow up in these countries, experiencing nature and learning the code in practical terms, these codes become second nature—part of a wider understanding of how humans should interact with nature and with each other.

The combination of rights and responsibilities creates a relationship with the natural world in which nature is no longer presented like some abstract museum piece, to be observed from afar behind a line of barbed wire. Instead it becomes a multi-sensory tangible experience with unique smells, sounds, and sights. The Right to Roam ensures that the government actively encourages people to go outside. It removes any sense that being in nature is a criminal activity and creates an inherent connection with nature. Right to Roamers feel that nature should be accessible for all and rights of access should be extended to give more people in towns and cities easy access to nature.

The closest thing to a right to roam in this country is our “rails to trails” projects. Americans, it appears, aren’t much for walking long distances. So most of our attention goes to bicycle trails. In Tallahassee, people can ride or walk the twenty-one miles down to the picturesque waterfront village of St. Marks. The Swamp Rabbit Trail in Greenville, South Carolina is a 22-mile multi-use (walking and bicycling) greenway that follows the banks of the Reedy River. And in Atlanta, people have multiple options including the Beltline and the sixty-mile Silver Comet trail. In America, if we want to “ramble”, we need to go to a park, a nature preserve, or an arrow-straight, paved, mini-roadway where we must give way to a steady stream of bicycles.

The Mt. Mitchell hike was a true ramble. We walked along overgrown roadbeds, scrambled down steep grades, and stepped across clear mountain streams. Rambling like that is good for the soul. It was, as they say in Europe, a multi-sensory tangible experience with unique smells, sounds, and sights that created an inherent connection with nature. I need to do it more often.

As far as I know, we had no right to wander down the side of Mt. Mitchell. Once we left the Park boundary, we had no legal authority to cross private property without the owner’s permission. We just did it. In Europe, we would have been protected by law. Here in the United States, who knows what might have happened in the back woods of the Appalachian wilderness. If we had made t-shirts for our hike, the front would have featured something about Mt. Mitchell and it being the highest elevation East of the Mississippi. But the back of the shirt might have recalled the 1972 movie Deliverance and read, “Walk faster. I think I hear banjo music”.

September 15, 2021

Why did it have to be Snakes?

I found it in the garden last week when I was mowing the lawn. The shed skin of a snake. I saved it for my wife because I knew she would like to share it with the kids at her school. She was indeed pleased, but when she shared our find on social media, her friends were less than impressed.

“OMG,” one person said. “No Way. Burn the house down.”

Others had similar reactions.

“Just had a heart attack,” one moaned.

“I would have died,” exclaimed another. (This one will remain nameless, but he used to reside at our address.)

Only one person—a fellow teacher—mustered a positive comment. “The kids will love this.”

Most people, it appears, agree with Indiana Jones. When he was lowered into an underground chamber in the 1981 film Raiders of the Lost Ark, he faced everyone’s worst nightmare.

“Snakes,” Indy said. “Why did it have to be snakes?”

What is it about snakes?

I spent over forty years managing zoos around the country and handled more than my share of snakes, but I still count myself among those people who suffer from a fear of snakes. It even has a scientific name—ophidiophobia. It is a common phobia that can be triggered by a variety of factors that sound familiar to me.

The gulf coast of Florida, where I grew up in the 1960s, was not the thriving metropolis it is today. St. Petersburg was a sleepy retirement village that was carpeted with miles of woodlands and abundant wildlife, including plenty of snakes. Snakes were a part of our lives growing up. We were taught to fear them, especially the ones that could kill us.

But my fear of snakes could also be intrinsic—a part of my DNA. Recent research has found that certain neurons in the brain only respond to snakes. These snake-dedicated neurons may be a legacy of our distant primate past since we share this bias toward snakes with monkeys. When primates evolved some sixty-million years ago, they adapted to living in trees, searching for food at night, and sleeping in the canopy during the day. Snakes creeping through those trees were among their deadliest enemies.

As my career advanced and I began doing education outreach programs on behalf of the various zoos I represented, snakes became a part of my life. It was the creature that audiences loved to hate. People often got up from their seats during my presentations and sometimes even left the room. I handled boa constrictors, ball pythons, and rat snakes. I learned not to recoil at the feel of their muscular legless bodies that were wrapped in a smooth, dry leathery skin. I marveled at their forked tongues as they tickled the hairs of my arm, picking up scent molecules to transfer to the “smell” organ inside the roof of their mouth.

I learned to overcome a powerful urge to recoil whenever I reached into a cloth bag to pull out a creature that terrified me. I handled snakes with feigned confidence and regaled my audiences with the importance of snakes to the ecosystem, all while trying to conceal my fear that one of the snakes might turn and bite me.

When we were growing up, if a snake came into our yard our dad dispatched it with a hoe. Later in life, that same man befriended a large black snake that lived in his tool shed. It seems my dad was more concerned with the mice that nibbled his seed packets than a big black snake that ate those mice.

My wife and I are similarly comfortable having non-venomous snakes inhabit our garden. We have seen a large, Eastern garter snake slithering into the iris bed on occasion. We also saw him swimming in the fishpond once. Garter snakes are known to eat fish, but at last count all of the goldfish are still there.

Snakes go through a process of sloughing the external layer of skin to allow growth. It is called ecdysis, and it occurs every few months, depending on how well they are eating and how fast they are growing. The shed snake skin I found in our garden was three and a half feet long. According to the Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles, Garter snakes don’t grow that large. So unless his skin stretched out when he was pulling out of it, the skin must come from something larger, like perhaps a gray rat snake.

For us, garter snakes and rat snakes are as welcome in our garden as box turtles and lizards. They are harmless residents of a healthy ecosystem. Venomous snakes, on the other hand will be dispatched without question.

The only concern I have with the snakes in our garden has to do with the location of that shed snake skin. I found it a few feet from the gnome home. Like the goldfish, I did a head count, and all of the little people are present and accounted for. But still, I wonder what kind of fence I could install to keep the snakes away from the gnomes. A rat snake might have a tough time telling a mouse from a three-inch tall gnome—even if he is wearing a pointy, red hat.

August 31, 2021

Lessons from the Zoo, Introduction, Part 2

In 1978, I learned that Bob Bean, my old boss from Busch Gardens, was looking for a general curator at his zoo in Louisville, Kentucky. I took the job in hopes that it would advance my career and save my broken marriage. My career flourished. My marriage did not. When my divorce was finalized in 1984, I moved back to Tampa—this time to direct the Lowry Park Zoo and to, once again, help build a new zoo. I also married the love of my life and began a lifelong partnership with Louisville zoo volunteer, Karen Liebert.

The cages I inherited at Lowry Park were mostly chain-link boxes of various sizes that housed lions, tigers, pumas, jaguars, bears, and primates. Two chimpanzees, Herman and Gitta, lived behind iron bars covered with heavy fencing that rendered them almost invisible, while otters and alligators swam in water-filled pits. Shena, the lone elephant, was confined to a small pen with a shelter about the size of a two-car garage.

It was a grim place, but by late 1985, money had been raised and construction began on a new zoo. For nearly three years, workers poured concrete, sculpted artificial rocks, and installed caging until we were finally able to plant grass, test waterfalls, and move animals into their new homes. One of the highlights of my zoo career came in the winter of 1988 when I witnessed Herman and Gitta step out of their new night house and walk on grass for the first time in many years.

Karen and I saw the completion of the Lowry Park Zoo in 1988, then moved to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, where I managed the Great Plains Zoo and Delbridge Museum of Natural History for a couple of years. By that time, we had led two trips to Africa, and she was expecting our first (and my fourth) son. When the Toledo Zoo announced it was looking for a deputy director, we jumped at the chance to move closer to family.

If I had to name a favorite zoo, it would be the Toledo Zoo. When I first visited there in the summer of 1991, it struck me as a unique blend of historic old structures and cutting-edge new animal exhibits. The thirty-acre site was compact and filled with interest. Intense, colorful plantings accentuated the architecture of ornate brick and stone buildings. It billed itself as America’s most complete zoo because of its museum, aquarium, and plant conservatory. It had a reputation for developing the latest in immersive zoo exhibits like the African Savanna with its one-of-a-kind Hippoquarium.

From my first project, the three-million-dollar Kingdom of the Apes that opened in 1993, to my final project, the Arctic Encounter that opened in early 2000, Toledo was a whirlwind of animal experiences. I traveled to Africa, South America, and Europe. I encountered Beluga whales and polar bears in the Arctic and stepped over blue-footed boobies in the Galapagos Islands. But after ten years in Toledo, I had the bright idea I wanted to retire from the zoo business and open a home inspection franchise in South Carolina. For some reason, that never took off. Maybe it was a combination of poor business acumen and the fact that the first day of my training took place on 9/11/2001.

The final stop on my zoo odyssey began in June 2004 when I re-entered the zoo world to take over a 700-acre park and zoo in Albany, Georgia, known as Chehaw. We revitalized a small zoo when we brought in black rhinos, flamingos, and cheetahs. I learned the importance of harvesting pine trees sustainably and maintaining the pine savanna woodlands of South Georgia by intentionally setting them on fire. Finally, at the end of 2015, I officially retired and found myself a part-time gig driving a mule wagon at a local quail hunting lodge.

In my career, I have traveled the world working with animals and viewing them in the wild. The number of animals I have encountered is beyond measure. I have watched animals being born and seen them take their last breath. I received animals that were rescued and brought to zoos as orphans from the wild, helped nurse them through sickness, and watched their lives unfold over decades.

I have had an impact on the lives of countless animals at seven different zoos, but they have had an impact on my life, as well. They have quite literally changed my life. So, back to the question, “What is my favorite animal?” I can’t name just one, but I can think of ten that are on the short-list.

Next week: Lesson 1, Showdown with an Elephant

August 30, 2021

Lessons from the Zoo, Introduction, Part 1

“What’s your favorite animal?”

That is the second question I get from people who have just asked me what I do for a living. I have been trying to answer it for nearly fifty years—first as a zookeeper, then as a zoo curator, and now as a retired zoo director. I have always answered it in the moment, which means the answer has not always been the same. I have, at times, said the elephant was my favorite animal because of some unique experiences I had with them early in my career. I answered hoofed stock when I remembered the astonishing variety of giraffes, zebras, and their kin that I came to know at Busch Gardens in the 1970s. I also loved the gorillas and polar bears that made an early impression on my career. But, at the end of the day, I’m not sure I have a favorite. It would be like trying to choose a favorite grandchild. I love them all.

I grew up roaming the woods of St. Petersburg, Florida, at a time when the Gulf Coast had wooded areas to roam. My dad worked in construction as a plasterer, so we never had much money. I was the oldest of four boys and served as my dad’s chief laborer. I mixed “mud” when he had a side-job plastering someone’s walls. I carried a five-gallon bucket and swatted mosquitoes alone in the darkness of some Florida bayou when he was out throwing his cast net on nights when the mullet were running. And I handed him tools when he was under the car repairing the brakes or changing the oil.

I can’t think of any defining moments from my childhood that would have predicted the course of my career. We had dogs, and I did love being in the woods—despite the abundance of rattlesnakes. But I was not that child who was always bringing home critters, and we didn’t have a zoo in my community. I did, however, study biology at Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. Somehow, that’s all it took—that and a chance visit to the zoo in Atlanta in the Spring of 1970.

The trajectory of my career was driven by ambition. I must have had a restless spirit as I moved from job to job, often in spectacular fashion. My first job, for example, came after I gave up the final year of a full-ride college basketball scholarship in Georgia to work as a zookeeper in Tampa. Busch Gardens introduced me to elephants, apes, big cats, and an array of hoofed animals while I pursued my degree in zoology at the University of South Florida.

After two years in Tampa, I landed an exciting position as a senior zookeeper at a new zoo that was being built in Toronto. I arrived in Canada in September 1973—a sunburned Florida cracker ready to face my first Canadian winter without any proper clothing. It was at the Toronto Zoo that I first experienced polar bears and wild-caught baby gorillas. And the Toronto Zoo sent me on the trip of a lifetime to tour the zoos of Europe, followed by a stomach-churning ocean voyage back to Canada.

I was one of a few Americans on a team of zookeepers from Canada, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Australia, and other parts of the world. I doubt there has ever been a more talented, diverse, and eccentric group of zookeepers assembled anywhere on the planet than those who came together to open the Metro Toronto Zoo. We endured primitive working conditions, low pay, harsh winters, and injuries from wild animals. But the results, at least from my vantage point nearly half a century later, were entirely worth it.

Opening an enormous zoo with thousands of animals was a complex undertaking. With animals arriving daily and their permanent homes still under construction, zoo officials rented holding barns all over the region. Conditions were often alarmingly makeshift. We had a few animal holding spaces on the property, but not nearly enough to accommodate the growing collection. So, on most mornings, zookeepers would strike out in trucks, cars, and even tractors, heading for the temporary holding areas that dotted the countryside—places like the Finch barn, the Johnson barn, the Sedgwick barn, and the old pig farm more than twenty kilometers away in Claremont. We dealt with icy, treacherous winter roads; isolated, lonely locations; and challenging animal medical conditions. We were kicked, bitten, and head-butted, and at the end of the day, we gathered at the Glen Eagles Pub to laugh at our tribulations. We labored long hours at the zoo and spent most evenings at the pub or playing broomball on frozen ponds. I had uprooted my wife and sons, moved them fifteen hundred miles to a foreign country, and proceeded to neglect them as I dove into my new job. It was a great time for my career, but not my finest hour as a father and husband. My marriage began to crumble.

Tomorrow: Louisville Zoo, Zoo Tampa, and Toledo

August 17, 2021

The Walking Man

“I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life,” Henry David Thoreau wrote, “who understood the art of Walking.” His 1862 article in the Atlantic magazine was titled, appropriately enough, Walking. A little over a hundred years later, singer / songwriter James Taylor took up the subject in a song that has become my anthem—the Walking Man. Now, here I am in what might be called my twilight years trying to be James Taylor’s walking man while understanding Thoreau’s art of walking. Some days, when my arthritis is acting up, I feel more like the aching man. But James Taylor’s lyric usually nudges me out the door. “While any other man stops and talks, the walking man walks.”

I look forward to my morning walk. It is part of my daily ritual along with getting dressed, having a cup of coffee, and brushing my teeth. Some days are better than others. It depends on the weather, my daily schedule of chores and errands, and how my worn-out old body feels. I am fortunate that I am physically able to walk, that I have a safe neighborhood in which to do it, and I have a family heritage of walking.

I usually walk alone listening to a podcast on my headphones. That is when I do my best thinking. I wrote this article in my head while on one of my walks. I try to walk through fatigue and injury, in all types of weather, dodging cars, lawn service trailers parked in the street, and the occasional dog running loose. I also enjoy walking with my wife. We talk more on our walks than we do when we are busy at home. It is, I think, good for our marriage.

When I began my daily walks, I tried to walk two miles and three miles on alternate days, but I have had to dial back a bit to ease my aching back. Now I try for about two miles a day with a couple of days off each week.

I obviously enjoy walking, or I wouldn’t do it. It is good exercise. I see interesting scenery, including birds and wildlife. And I get to be a nosy neighbor as I casually inspect houses and yards. Karen and I have a good time with this. When are they going to mow their lawn? Why did they paint their house that color? And, a pet peeve, why is that car parked on the lawn and not in the driveway. And why has it not moved in over a week?

I regularly encounter fellow walkers. These include the serious walkers (fast pace, head down, arms pumping); the strollers (Thoreau calls them saunterers); the buddy walkers locked in conversation as they go; the cell-phone talkers; the dog walkers; and the half dozen walkers on the golf course who walk up and down the fairway side by side in a line. My wife and I call them the crime scene finger-tip search team.

I come from a long line of walkers, although it skipped a generation with my parents. They didn’t walk much, but my grandparents sure did. When my brothers and I spent weekends with Grandma Porter, she walked us all over St. Petersburg, Florida. We walked to the grocery store and drug store when she needed supplies. We walked to the ice cream shop after dinner. When she needed to go to downtown, she walked us four blocks to the bus stop on Sixteenth Street. When the bus dropped us downtown in Williams Park, we walked through the park to Maas Brothers Department store, down to the pier, and other destinations as needed. Then it was back to the park to catch the bus home. It wasn’t like she couldn’t get a ride in someone’s car. She just didn’t want a ride. She had her own two feet—and the City bus.

It is hard to imagine, but there was a time when exercise wasn’t a thing. Grandma Porter didn’t walk because it was good for her health. She wasn’t worried about her cardio workout or how many steps she got in. She was just a walker. Sometime in the late 1800s, she walked behind a covered wagon with her family as they trekked from the Florida panhandle to Nacogdoches, Texas—a journey of more than six-hundred miles. According to Google Maps, I could drive that trip in ten hours. My grandma’s walk, at about three miles an hour, would have taken several months. That was a walk of Thoreau proportions.

In his essay on walking, Thoreau said, “I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.”

Four hours is a heck of a walk, but he only walked in the fields, forests, and woods. And he embraced the idea of sauntering, so he probably stopped frequently to sit on a log and contemplate nature. Thoreau would have laughed at my pathetic excuse for a walk. I am out for less than an hour and the only wildlife I see are the squirrels, rabbits, and birds that peer at me from my neighbors’ lawns.

A real walk, according to Thoreau, is when “you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again—if you have paid your debts, and made your will, and settled all your affairs, and are a free man—then you are ready for a walk.”

Good grief. Who can measure up to that? The only thing that gives me hope is that he also said, “[Walking] comes only by the grace of God. It requires a direct dispensation from Heaven to become a walker. You must be born into the family of walkers.”

There, I do have some “street creds”. I do come from a family of walkers, and I have Grandma Porter’s “dispensation”. So I will continue my daily walks with Thoreau’s inspiration in my heart and James Taylor’s anthem in my head. “Moving in silent desperation toward a hypothetical destination. Who is this walking man?”

August 2, 2021

Beware The Dog – Part 2

All of these artificial and ever-changing boundaries must be confusing to our dogs. They seem to figure out their own homes and yards, but they can get befuddled at the edges. My wife was attacked and bitten by someone’s dog as she ran in the street in front of the dog’s house. In fact, we have heard reports of several walkers in our neighborhood being bitten by dogs that ran out into the street after them. I suppose the dogs were protecting their territory, but someone needs to tell them that their authority stops at the curb.

If my wife and I decide to sell our home, it will become someone else’s patch and they can guard it as they see fit. We will move to a new property and set about marking and protecting our new territory. This, it seems to me, is what the American Dream is all about. I can live where I want, and I can protect where I live with any means necessary. Maybe we’ll get a dog that was bred to be a guardian—a dog like the Doberman pinscher, the bullmastiff, or the boxer. Many of the best guard dogs, however, are general purpose farm dogs like the German shepherd. This breed has long been synonymous with “police dog” and should be a good dog to serve me and protect my property. But the two most recent dog bites in my neighborhood have been German shepherds that attacked runners in the street. So, I’ll probably just stick with a barking dog to warn me of danger.

My son’s golden retriever Libby came to stay with us recently. Ian’s Atlanta home was on the market and needed to be free of dog hair for a couple of weeks. Libby has visited us plenty of times but never for an extended stay. For the first day or two she was curious about everything, sniffing around the house and yard, and watching through windows as cars and people passed by our house. But by the end of day two, she was more protective of her new territory. Somehow, she had decided that people walking in the street were a threat, and the cars stopped at the stop-sign and idling across the road needed to move on. The dog whose idea of dealing with a stranger was once a wag of the tail and a gentle “woof” on their approach followed by licking them into submission, has become a serious guard dog.

Libby and I are carrying on that time-honored tradition of protecting our home—a home that could be repossessed by the bank if I don’t pay my mortgage, on the property that could be seized by the county if I stop paying my taxes, on the land where Native Americans roamed before European settlers kicked them out to the Oklahoma Territory. But I still claim it as “mine”, and I have a fence, a shotgun, and a guard dog to prove it.

July 26, 2021

Beware the Dog – Part 1

Libby & Alice. Guard dogs come in all sizes.

Libby & Alice. Guard dogs come in all sizes.I see them as I walk around my neighborhood, peering at me through fences, barking at me in living room windows, and—in at least one unfortunate case—straining against a chain in someone’s back yard. They are guard dogs.

The American Kennel Club recognizes seven dog breed groups, including Sporting dogs, Working dogs, Herding dogs, Hounds, Terriers, Toys, and Non-Sporting dogs. But the AKC does not have a category for guard dogs. All dogs, I suppose, are expected to be guard dogs.

Guard dogs, or watchdogs, probably date to the first co-habitation of humans and wolves. Their original job was to protect humans and their domestic herds from dangerous animals and unrecognized humans. They are seen in ancient Greek mythology and were used extensively by the Romans. A Second-Century mosaic of a black dog was found in a house in Pompeii. It was enclosed by the Latin quote “Cave canem!”, which means “Beware the dog!”. We humans, it seems, have long been protective of our property.

Control of property goes back to the very founding of our country. Two hundred fifty years ago, British colonists in the “new world” decided they wanted to break away from British rule and create their own nation. After our success during the American Revolution, we have been obsessed as a nation with freedom, independence, and our right to private property. My wife and I have a piece of property. We own a home for which we have a mortgage. We also pay taxes on that home’s carefully defined plot, which is located in a particular neighborhood, in a city and county in the state of Georgia. But is it really ours?

Yard dogs

Yard dogsThe United States, our homeland, was taken by white settlers from the indigenous people who already lived here and the State of Georgia is land that was seized by the British Empire in the 1700s to protect its North American colonies from the Spanish empire in Florida. In fact, all of the boundaries and borders that we like to claim and defend are artificial. Somebody, or some group, bought them or took them by force, then defined them and sold them to us. Yet, we guard them with our lives. As property owners, we put up signs and fences to keep people out. We install elaborate alarms and cameras that connect to our smart phones to warn us of intruders. And we acquire guns and dogs for when people ignore those warnings.

July 8, 2021

At Home with the Gnomes

My wife is particular about the creatures that occupy her garden. Birds of all types are welcome. The neighbor’s cat is not. Turtles that munch on clover are welcome. Deer that mow down her daylilies are not. This even extends to inanimate objects. Frogs live in our pond and frog figurines surround it. But not all figurines are allowed. We only have frogs in natural poses. You won’t find any frogs playing banjos in our garden.

And then there are the gnomes. There is nothing natural about them, but they have somehow multiplied over the years and lurk in several corners of the garden. There are large ones and small ones, some painted and some au naturel (not naked, just unpainted). We have so many of them, they needed a place to live. That’s why I finally completed that gnome home I have been promising to make.

According to the New World Encyclopedia, a gnome is a type of legendary creature that lives in dark places in the depths of forests and, more recently, in gardens. Modern traditions portray gnomes as small, old men wearing pointed hats. But, historically, the term “gnome” has included a variety of creatures. Goblins, for example, come out of German and British folklore and are usually described as troublemakers as opposed to the more benevolent fairy. Elves are from Norse mythology and leprechauns are diminutive supernatural beings in Irish folklore, usually depicted as small, bearded men wearing a coat and hat.

The earliest appearance of gnome-like statues was the representation of gods in ancient Roman gardens. It is believed that the very first contemporary garden gnome (with its iconic red hat), was made in Germany and brought to England in the 1840s. Gnomes have been a presence in the English garden—and later in North America—ever since.

The “traveling gnome” was introduced in the 1970s and became widely popular during the 1990s when people began stealing gnomes and taking them traveling. Thieves usually sent photographs of the gnomes to the owners, showing them that their minions were safe and sound, and enjoying their newly gained freedom and independence. Over time, the prank became popular on a global scale, with many cases of stolen traveling garden gnomes appearing in photographs in front of famous landmarks worldwide. Today, we even see a gnome front-man with a cute British accent for a well-known travel website.

Most gnomes—whether they be satyrs, pans, dryads, elves, brownies, or goblins—hoard treasure and interact mischievously or even harmfully with humans. But some gnomes, it is said, are helpful to plants and animals. Judging by my wife’s success in her garden, those are the ones that live with us.

Our gnomes are only active after dark and appear to come inside the house on occasion. Some people have ghosts or poltergeists. We have gnomes. Our gnomes rank somewhere between mischievous leprechauns and benevolent fairies. They nurtured us through the pandemic by giving us a sense of peace and calm. They help my wife with her plants in the garden, nudge both of us to go on long walks, and stir up gentle breezes to tickle the wind chimes during my afternoon naps on the porch.

On the other hand, when my wife comes into the room and asks me to call her cell phone so she can locate it, I’m pretty sure the gnomes have hidden it. When we are watching TV on a clear, calm evening and the electricity goes off—just long enough to force a reset of all the clocks and electronics—that is classic gnome behavior. And recently, when we were headed out for our evening walk and discovered that a box turtle had somehow clambered up a small step and plopped into the fishpond—well, there is only one explanation for that.

Early humans created gnome-like creatures to explain the unexplainable. Every culture, it seems, has a version so there must be something to it. As a Christian, I see God’s handiwork in my life, which might include sending the gnomes as his angels. That is why I built the gnome home. It not only looks nice nestled in the garden, but it also makes our little buddies feel welcome and gives them a place to call home. Maybe, now they will spend more time in their own yard and less time hiding phones and dropping turtles into our fishpond.

June 19, 2021

The Silverback

As a young zookeeper at Busch Gardens in the 1970s, I was in awe of him. Hercules was a four-hundred-pound, male gorilla—a silverback. Hercules lived with his mate Megara but, to the best of my knowledge, he never sired any offspring. In those days, we assumed that if you put a male and female gorilla together, nature would take its course. Today, we know that gorillas live in stable family groups numbering from six to thirty animals. Each group is led by one or two mature males that are related to each other, usually a father and one or more of his sons. The sons learn their roles from the silverback. Hercules, however, was taken out of the wild as an infant. He never had the opportunity to learn how to be a father.

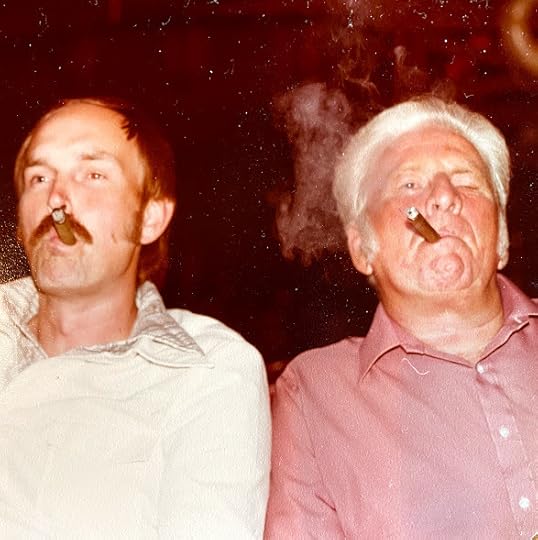

I learned how to be a father from my dad. Jim Porter was the silverback of our family. He served in the Army during World War Two—a sergeant in the Military Police. After the war, he trained as a plasterer and raised four boys. I was the oldest and worked as his chief laborer. I mixed “mud” when he had a side-job plastering someone’s walls. On nights when the mullet were running and he was out throwing his cast net, I carried a five-gallon bucket and swatted mosquitoes in the darkness of some Florida bayou. And I handed him tools when he was under the car repairing the brakes or changing the oil. Like a true silverback, he was quiet and patient—although we did feel the sting of his belt on our bare bottoms from time to time. It may not be fashionable in today’s society but in those days our house, like the gorilla family, was a patriarchy.

Gorillas are native to the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. They are the largest of the apes—robust and powerful animals with black skin and hair, and thick powerful bodies. Males are about twice the size of females, weighing in at up to five hundred pounds, and have a saddle of gray or silver hairs on the lower part of the back—hence the term “silverback”. The mature silverback makes all the decisions for the troop. He mediates conflicts and he is responsible for their safety and well-being. If the group is attacked, the silverback will protect the group, even at the cost of his own life. But, oddly enough, gorillas don’t fight with each other very often. They use ritualized displays that include standing on two legs, running sideways, throwing vegetation, and chest-beating with cupped hands. These impressive displays of agitation usually end with a sidelong glance at the offender that might, in modern parlance, be called a “stink-eye”.

The last silverback gorilla I worked with was Akbar. I wrote about him in this excerpt from my memoir, Lessons from the Zoo, Ten Animals That Changed My Life.

“One of my first projects as Deputy Director of the Toledo Zoo was the three-million-dollar Kingdom of the Apes area that opened in 1993. Toledo had an impressive collection of great apes that included chimpanzees, orangutans, and two families of gorillas. They lived in a symmetrical, rectangular, 1970s–era facility, with each of the four groups housed in a section that consisted of off-exhibit holding cages, a small indoor glass-fronted dayroom, and a slightly larger open-air outdoor space with a concrete floor. It was all hard-scape—concrete, glass, and steel. No animals had access to grass.

The renovation would improve the holding cages and add an eighteen-thousand-square-foot outdoor Gorilla Meadow and a three-story indoor dayroom. The old outdoor spaces would have a tall cage structure added to increase the vertical space, and grass would be planted to replace the concrete floor. It was a remarkable transformation, both visually and for the quality of life of the animals.

On Monday, May 17, 1993, I gathered with my colleagues to watch the male gorilla Akbar peer out of the holding area and carefully test the grassy surface of the new Gorilla Meadow exhibit. As soon as he determined it was safe, he allowed females Happy, Malaika, and Elaine to follow. The thrill of seeing the gorillas step into the sunshine was tempered by the concern we felt as Akbar carefully inspected the walls and fences of his new home. Only after he completed his tour of the perimeter and did not find any escape routes did we relax and celebrate our success.”

Akbar was raised in a family group, so he knew what it meant to be a silverback. When entering an unfamiliar space, his job was to check out the area to make sure his family would be safe, just like our father always did for us. My brothers and I were not afraid of our dad but, much like the gorilla family, we never had any doubt about who was in charge. I don’t remember him throwing any vegetation or beating his chest with cupped hands, but dad must have used some kind of ritualized threat displays, because he never raised a hand to us in anger. All he had to do was look at us out of the corner of his eye, and we knew we had better listen-up. When he said jump, we didn’t ask why. We just asked, “how high?”. And when we were sitting in his chair, he snapped his fingers and we moved out of his way.

Jim Porter died in June 2004—seventeen years ago this month. I still miss him. My father-in-law (the silverback of my wife’s family) died a few months ago. We will bury him the Sunday after Father’s Day. I am going to miss him, too. For the first time in our lives, my wife and I will not have a silverback to honor on Father’s Day. Their passing marks the end of a generation.

My brothers and I recently traveled back to our hometown of St. Petersburg, Florida for a weekend of golf, a baseball game, and some reminiscing. Dad featured prominently in our collective memory. As I look at the fine men my brothers have become and at how much we love each other and enjoy each other’s company, I realize how fortunate we were to have the upbringing we did. Our dad is the strong, male role-model that lives-on in the hearts and memories of the Porter brothers. We may not have a father to send a card to, but we sure have one to honor on Father’s Day. Today’s fathers—myself included—are not what they once were. If you have any doubt, watch me snap my fingers when my wife is in my chair and see what happens.