J.D. Porter's Blog, page 4

August 4, 2023

National Dog Month

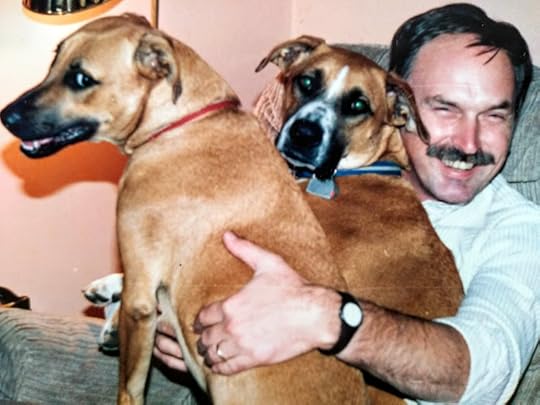

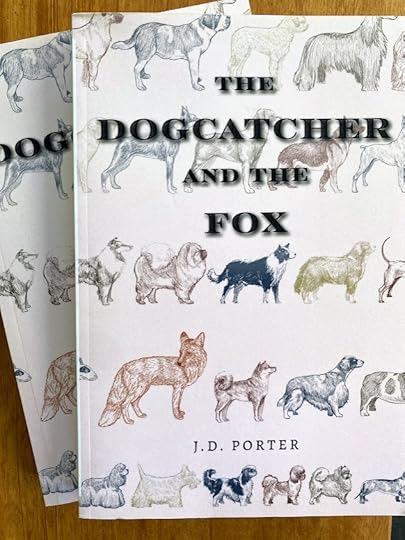

To say I love dogs would be an understatement. Dogs have been a part of my life since the day I was born. I grew up with Mitsy, Tippy, and Snoopy. Soon after we were married nearly 40 years ago, Karen and I rescued Simba and Jana (pictured above) and when they passed, we rescued Chelsea and Bexley. I have written extensively about dogs and will revisit some of my favorite blogs in the coming weeks. But one of my favorite dog-writing projects was my second novel, The Dogcatcher and The Fox.

July 16, 2023

The Zookeeper

“What’s your favorite animal?”

As I document in my memoir, Lessons from the Zoo, Ten Animals That Changed My Life,

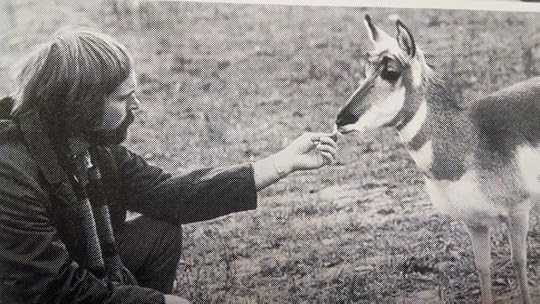

that is the second question I get after people ask me what I did for a living before I retired. I have been trying to answer it for over fifty years—first as a zookeeper, then as a zoo curator, and now as a retired zoo director. I have always answered it in the moment, which means the answer has not always been the same. I have, at times, said the elephant was my favorite animal because of some unique experiences I had with them early in my career. I answered hoofed stock when I remembered the astonishing variety of giraffes, zebras, and their kin that I came to know at Busch Gardens in the 1970s. I also loved the gorillas and polar bears that made an early impression on my career. But, at the end of the day, I’m not sure I have a favorite. It would be like trying to choose a favorite grandchild. I love them all.

I grew up roaming the woods of St. Petersburg, Florida, at a time when the Gulf Coast had wooded areas to roam. I can’t think of any defining moments from my childhood that would have predicted the course of my career. We had dogs, and I did love being in the woods, but I was not that child who was always bringing home critters. I did study biology at Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. Somehow, that’s all it took—that and a chance visit to the zoo in Atlanta in the Spring of 1970.

I must have had a restless spirit because I moved from zoo to zoo, often in spectacular fashion. My first job, for example, came after I gave up the final year of a full-ride college basketball scholarship in Georgia to work as a zookeeper in Tampa. Busch Gardens introduced me to elephants, apes, big cats, and an array of hoofed animals while I pursued my degree in zoology at the University of South Florida.

After two years in Tampa, I landed a position as a senior zookeeper at a new zoo that was being built in Toronto. I arrived in Canada in September 1973—a sunburned Florida cracker ready to face my first Canadian winter without any proper clothing. I was one of a few Americans on a team of zookeepers from Canada, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Australia, and other parts of the world. I doubt there has ever been a more talented, diverse, and eccentric group of zookeepers assembled anywhere on the planet. We endured primitive working conditions, low pay, harsh winters, and injuries from wild animals. But the results, at least from my vantage point a half century later, were entirely worth it.

During my career, I had an impact on the lives of countless animals at seven different zoos. And they had an impact on my life, as well. So, back to the question, “What is my favorite animal?” I can’t name just one, but I can think of ten that are on the short-list. They are in my memoir, and I will be giving away 5 copies of Lessons from the Zoo, Ten Animals That Changed My Life in honor of National Zookeeper Week. Details are on my website: https://jdporterbooks.com/.

May 14, 2023

The Matriarch – A Mother’s Day Tribute

We faced each other like a couple of gunslingers at high noon. I was a young zookeeper, armed with a three-foot-long stick called a bull hook. My opponent brought his pair of impressive ivory tusks and six-thousand-pounds of bulk. Bwana stood about twenty yards away, facing me with his trunk up and his ears fanned out in a threat display. He was a nine-year-old male African elephant, and he was testing me to see who was in charge.

If he had been in the wild, there would have been no doubt who was boss. It would have been his mother. That’s because wild African elephants live in a matriarchal society—a world that is dominated by the females.

A mother elephant will usually try to set an unruly youngster right with a gentle nudge in the right direction or, if that doesn’t work, a sharp slap with her trunk. And when a young male like Bwana approaches puberty at ten to twelve years of age, his mother probably won’t try to coax him back like I did. At that age, she is more likely to force him out of the herd. Adult males lead solitary lives or live temporarily in a smaller herd with other young bulls until it is time to breed.

Another matriarchal society that some might find surprising is a fearsome, ocean-dwelling creature that hunts in packs, chases seals for sport, and can kill a great white shark. That’s right, Killer Whales are also ruled by their mothers. Killer Whales, or Orcas, are the largest member of the dolphin family. They live in female-led pods, where they hunt together and share responsibility for raising the young and taking care of the sick or injured.

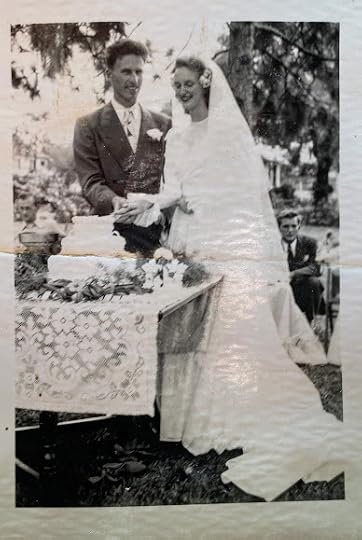

Mom with David, Doug, Don, and Danny

Mom with David, Doug, Don, and DannyThinking about matriarchal societies seems like a good way to remember my own mother on Mother’s Day. She came to motherhood at an early age and took it on with tenacity. She married my father at eighteen and had me a year later. She tragically lost her second child—her only daughter—in childbirth but went on to have three more sons. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Carol Porter is how unremarkable her story is. But I am glad we set aside a day for me to continue to honor her, even though she would insist she was just doing her job as a mother.

I should honor my wife, too. She may not be my mother, but she is the best mother I know. And her motherly love can even cross species barriers. In the late 1990s, a female gorilla in a zoo at which I worked gave birth but was unable to care for her baby for a while. When zookeepers stepped in to care for the infant, we had to find surrogate mothers to hold the baby on a regular basis and to bottle-feed it around the clock. A group of dedicated volunteers—including my wife—agreed to take turns caring for the infant gorilla until its mother was able to resume her duties.

In fact, I can think of no better example of motherhood in the animal kingdom than the female gorilla. Gorillas live in troops of a few—to a few dozen—members that are led by a dominant, adult, silverback male. Zoo Atlanta recently announced the birth of a gorilla, and they report that the infant appears healthy and strong, is nursing normally, and is receiving appropriate maternal care. I would expect nothing less from a gorilla mom.

Zoo visitors who are fortunate enough to see the infant might note that gorillas are born with an instinctive ability to hold on to their mothers’ chests but, in most other respects, they are helpless. Mothers support their babies for the first few months of life but, unlike humans, gorilla mothers seldom allow other gorillas to hold or carry their infants. Babies learn to crawl and ride on their mothers’ backs at about three months of age and may continue to ride on their mothers’ backs, chests, or legs for three or four years. If we had a Mother’s Day for the animal kingdom, mother gorillas would be high on the list of honorees.

We humans are, I suppose, neither matriarchal nor patriarchal—although America seems to be a more gorilla-like patriarchal society. My home growing up was certainly male dominated. My mom was outnumbered by my three brothers, my dad, and me. The toilet seat was always up in our house.

But that’s not to say my mom didn’t exert her influence. She could, at times, seem as powerful as a hurricane or as gentle as a summer breeze. She could bandage a skinned knee, soothe an injured ego, or send us outside to break a switch off the willow tree so she could use it on our bare behind.

My mom stayed home until my youngest brother was in school then she gave up that quaint notion that the woman’s place is in the home. She got a job with Bell Telephone and stayed with them for the rest of her working life.

She died a few years ago and I miss her terribly. I wish I could send her a card or call her on Mother’s Day to tell her I love her—and to thank her for not forcing me out of the herd when I reached puberty.

J. D. (Doug) Porter is a retired zoo director who writes about animals, nature, and the outdoors in his books and on his website: jdporterbooks.com. He lives in Atlanta and is the author of two novels and a memoir, Lessons from the Zoo: Ten Animals That Changed My Life.

October 23, 2022

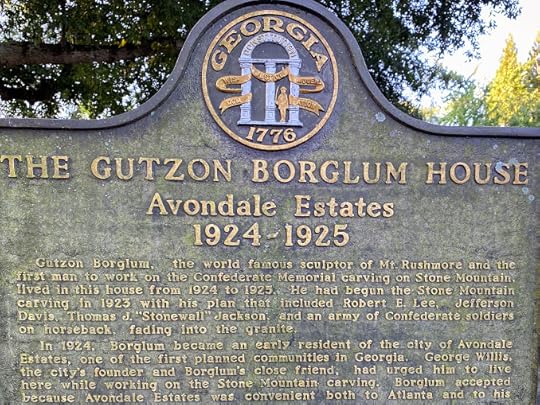

The Gutzon Borglum House

Gutzon Borglum house

Gutzon Borglum houseI have long been an admirer of Gutzon Borglum’s monumental carvings on Mount Rushmore. We lived in South Dakota for a few years and made several trips to see them. So imagine my delight when we happened upon a historic marker bearing his name on one of our evening walks. Karen and I live in Avondale Estates, a historic suburban neighborhood outside Decatur. So, apparently, did Gutzon Borglum for a short time.

Avondale Estates was founded in 1924 as one of Georgia’s first planned communities. Everything in the one-thousand-acre development sprang from rolling, pastoral farmland. The streets and homes were carved out of pastures. The lake was created by excavating a depression and damming a creek. And the downtown was built from scratch at the intersection of Covington highway and Clarendon avenue—a striking and incongruous replica of an English Tudor village.

According to the marker, Borglum moved to the house at 10 Avondale Plaza in 1924 at the invitation of the city’s founder and his close friend, millionaire George Willis. Borglum was drawn to Avondale Estates because it is located eight miles east of the Gold Dome in downtown Atlanta and about halfway to another dome—a giant dome of rock that juts up from the surrounding plains. It is called Stone Mountain.

By the time he moved into my neighborhood, Borglum was a well-respected sculptor. Though he grew up on the frontier of the American West, he moved to Paris to study art while still in his teens. He worked in France, Spain, and England before returning to America in 1901 to make a name for himself.

Back in this country, Borglum created a number of statues and monuments. One of his works was a colossal head of Abraham Lincoln that he carved out of a block of marble. It was eventually placed in the rotunda of the Capitol Building and it inspired Helen Plane, President of United Daughters of the Confederacy, to contact Borglum. Her group wanted him to carve the head of Robert E. Lee on the side of Stone Mountain as a monument to the Confederacy.

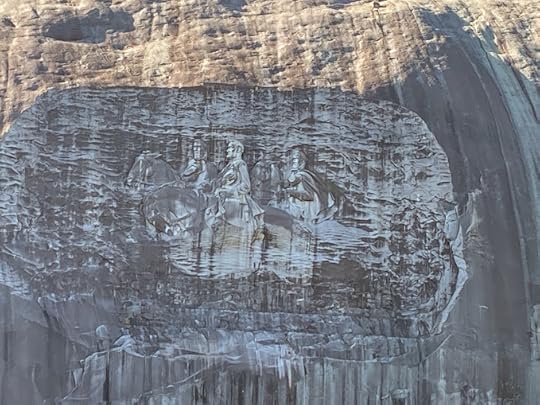

Borglum was an ambitious, 48-year-old artist and sculptor who visited the site in 1915 and agreed to the project but soon had much bigger plans. His proposal featured a massive relief carving of four horsemen—Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis and J.E.B. Stewart—riding across a 1,200-foot-span of the mountain’s eastern face. And, as it turned out, he would finance the project from an unexpected source.

At the same time Borglum was drawing up his plans for Stone Mountain, the epic silent film “Birth of a Nation” was being released. The movie about the Civil War and Reconstruction opened in January 1915 and grossed an astonishing $60 million in its first run. It also inspired a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization that became a major funder of the memorial. Helen Plane worked out a fundraising scheme whereby an Atlanta theater donated its box office proceeds from a screening of the film to the Confederate memorial at Stone Mountain.

The project was halted when the United States entered World War I, but Borglum was back on the job soon after the war ended. He was photographed in June 1923 with a jackhammer in hand, doffing his hat for the camera as he leaned off the side of the mountain in his harness.

Borglum’s technique for carving on such a massive scale began with models that he was able to scale up to a monumental size. He used dynamite to blast away tons of rock, giving him and his team a rough shape. Next they dangled over the stone face of the mountain and drilled a honeycomb of holes to a precise depth. This allowed them to shed even more rock and refine the carving. Finally, it was down to hammers and chisels to make the stone come to life.

By early 1924, Borglum had removed enough rock on the mountain to host a dinner party on a ledge that would become the shoulder of Robert E. Lee. A photograph shows Borglum, his wife, and son standing beside a long table with more than a dozen dignitaries seated for a formal dinner.

But work soon stalled. Borglum’s scale of carving wasn’t the only thing that was massive. So, reportedly, was his ego. The people who had hired him grew tired of his “delusions of grandeur” and sometime in early 1925, they fired him. Borglum, true to his reputation as a temperamental artist, destroyed his models in a fit of anger. But those models were the property of the people who paid for his services, so they had a warrant issued for his arrest.

Borglum hastily packed his bags at 10 Avondale Plaza and, before the police could find and arrest him, he raced out of Atlanta and into the history books. He landed on his feet with a new project on a mountain named after Charles E. Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

The Great Depression of the 1930s and the country’s entry into World War II stalled the Stone Mountain project and the Confederate memorial remained unfinished for decades. Then, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, the state of Georgia purchased Stone Mountain Park in the 1950s and signed legislation to establish a state authority to run the park. The state and the authority agreed to finish the carving and in 1970, the memorial was finally dedicated.

Some say the carving is offensive and should be blasted off the mountain. But perhaps it is no more offensive than having the likenesses of slave-owning presidents memorialized on a mountain in Western South Dakota. Maybe it is a good reminder of a darker past and a warning that sinister tendencies still lurk in our society.

It seems ironic to me that Stone Mountain Park with its massive monument to the ideals of the Southern Confederacy is now freely enjoyed by everyone. On a recent visit, I saw many people of color walking the trails, riding their bikes, and enjoying family picnics in the shadow of the monument.

The house that Borglum inhabited 10 Avondale Plaza was also built and most likely inhabited by people with racist inclinations. But today, our neighborhood is a vibrant, diverse community where people of all types stroll its sidewalks. Both Avondale Estates and Stone Mountain are clear evidence of a healthy multiracial, multiethnic society that the people who hired Borglum and developed the monument sought to deny.

Doug Porter lives in Decatur and writes about animals, nature, and the outdoors in his books and on his website: jdporterbooks.com

August 11, 2022

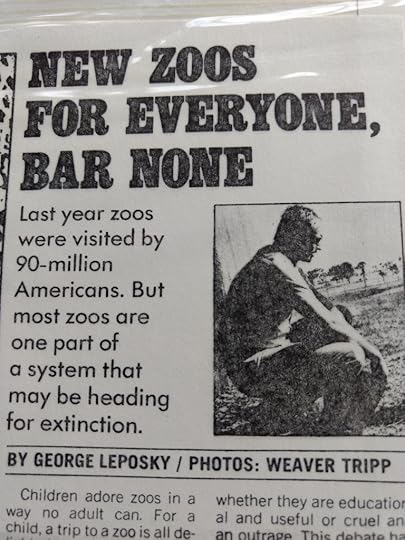

Zoos continue to teach about our world

Are zoos heading for extinction? That was the speculation by George Leposky when he published his article New Zoos for Everyone, Bar None in the St. Petersburg Times Floridian Magazine. He was obviously wrong because the story ran fifty-years ago on June 25th, 1972, and zoos are still around. But it was a fair question because most zoos—including our own zoo here in Atlanta—were grim places in those days. Leposky noted what he called an “uneasiness in the human attitude toward zoos” as he questioned whether zoos were educational and useful or cruel and an outrage.

I recall Leposky’s article because he interviewed me—a twenty-two-year-old zookeeper at Busch Gardens. My career choice was inspired by a visit to the Atlanta zoo and took me on an unlikely path to work at and manage zoos in Tampa, Toronto, Louisville, Toledo, and Albany, Georgia. I came full circle this year when I retired to Decatur and became a member of Zoo Atlanta.

As Leposky accurately foretold, zoos did become scientific and educational institutions which helped us place our civilized existence in perspective. For half a century, I helped zoos and aquariums evolve and become conservation centers that provide high-quality environments for the animals. I worked in big cities where we poured millions of dollars into our zoos and aquariums, and in small towns that required grit, determination, and ingenuity to provide more modest, but first-rate facilities. Attendance at zoos soared over the decades as people came to value their connection to the animals. These institutions have evolved into vital parts of our human communities. But what about the animals? There continues to be a nagging doubt in the minds of some. Are zoos really humane? Wouldn’t the animals be better off in the wild?

As 2020 began, that question came under fresh scrutiny when animals in the wild were under assault. During the Australian bushfire season of 2019-2020, billions of animals were killed or displaced, including tens of millions of mammals, birds, and frogs along with a staggering two billion reptiles. In the Amazon, those areas that were not being logged were burning. Logging roads were also snaking through the remote jungles of Central Africa allowing animals like chimps and gorillas to be consumed as “bush meat”. Indonesian forests were being cleared for palm oil plantations and the Arctic sea ice was—and still is—melting. Today, there is little wild left on earth. Zoos might be the only hope for animals.

Then, later in 2020, we were engulfed in a global pandemic and a new wildlife crisis emerged. Zoos and Aquariums were forced to shut down, with Disney alone laying off an astonishing 27,000 employees at one point. But fortunately, it would seem, we had a plethora of amazing digital, high-definition animal programs to watch. I saw things onscreen that I never dreamed of seeing in the wild—even after a half century of studying wild animals around the world. Perhaps these virtual experiences might make zoos obsolete.

As the coronavirus pandemic progressed, I attended virtual church and virtual Sunday school. My wife was forced to become a virtual schoolteacher as businesses around the world converted to remote work. But, as we hunkered down in our homes, I don’t believe I heard a single person say, “These virtual experiences are great!” Nobody has suggested that they prefer virtual sporting events to being present inside the stadium. We are programmed to enjoy things as a group. We want to be in church together, we want to attend live sporting events and concerts. And just look at how difficult was for us to stay out of restaurants and bars.

Ironically, it might be the pandemic that could save zoos as we take another look at the idea of replacing live animals in zoos with high-tech, virtual zoos. Zoos have made remarkable progress since I began my career. Modern zoos and aquariums, like ours in Atlanta, combine elements of natural history museums and botanical gardens under one comprehensive umbrella. Animals live in habitats that closely replicate their homes in nature and zookeepers spend their days training animals to be comfortable in their homes much like I train my dogs to be comfortable in my house.

We need zoos—both for our own social wellbeing and for the sake of the animals. We humans created parks, golf courses, museums, zoos, and aquariums because they are vital components to a civilized community. In his 2018 book, Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life, author Eric Klinenberg suggests that communities flourish when they value and preserve something he calls social infrastructure. He offers libraries, bookstores, churches, and parks as examples. I would add zoos and aquariums to that list.

So, to the people who want to abolish zoos altogether, I say not so fast my friend. It is zoos and aquariums that have developed the ability to live with animals. This is something that is becoming more important for animals as their wild habitats disappear. Perhaps we should think about living together with animals in a global community of zoos, game parks, aquariums, and marine parks. We need to assimilate animals into our lives, not separate them from us.

Now, as zoos and aquariums try to figure out how to operate in a post-COVID world, we must rally around them. They need donations, support, and even our tax dollars now more than ever—not because we place the needs of animals above humans, but because zoos and aquariums are as much a part of the social infrastructure of our communities as parks, libraries, and schools. As George Leposky noted half-a-century ago, our twenty-first century, COVID ravaged zoos will “require public support – moral and financial – to do what we expect of them. Should that support not be sufficiently forthcoming, zoos are indeed likely to become extinct.”

That would be a tragedy—for the animals and for us.

AJC Opinions Page, 11 August 2022

May 19, 2022

It Takes a Village

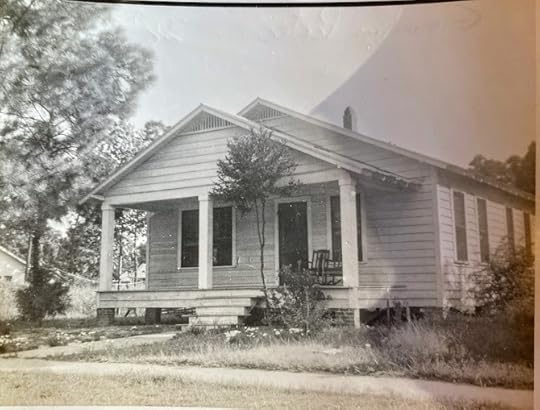

Grandma Porter’s House on 38th Avenue

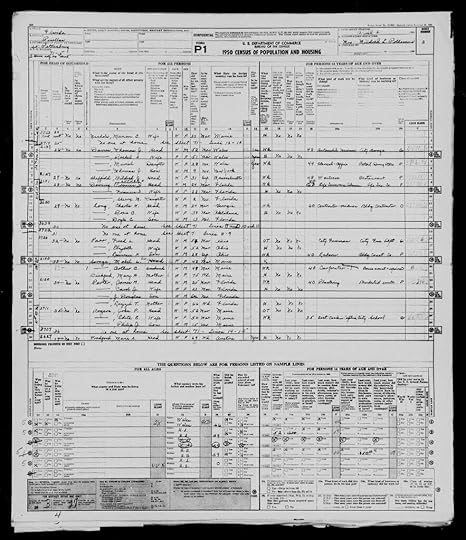

Grandma Porter’s House on 38th AvenueYou have to be of a certain age for your name to appear on the 1950 census. My name made it—just barely. Sometime in April of 1950, a census enumerator named Mildred Poldemus knocked on the door at 2120 38th Avenue North in St. Petersburg, Florida. On her carefully handwritten form, she noted the residents: James M. Porter, a twenty-five-year-old plasterer, Carol, his twenty-year-old wife, and Lizzie, his sixty-six-year-old mother. Even though James was living in his mother’s house, he—being a male—was listed as the head of the household. Also in residence that day was James and Carol’s five-month-old son whose name was listed as J. Douglas—yours truly. This is a bittersweet snapshot in time since I am the only person in that household still alive. Even the house is gone. It was demolished in the 1970s to make way for I-275.

Census form

Census formThose 1950 Census records were released in April, exactly seventy-two years after enumerators like Mrs. Poldemus began knocking on doors. About forty-six million American houses were canvased and a little over 150 million people were counted. Those millions of census forms, painstakingly filled out by hand in ink, were just posted online by the National Archives and Records Administration, which by law has kept them private until now. Census records are confidential for seventy-two years to protect respondents’ privacy.

The word “census” is Latin in origin. The Romans were counting their citizens by around the middle of the first millennium B.C. But few if any of those counts would meet today’s definition, which is essentially to count everyone in a given place at a given time. The first census in the United States took place beginning on August 2, 1790. Although it took months to collect all the data from households.

During the 1950 census, according to the New York Times, the post-WWII baby boom was in full swing, the average family earned $3,300, and gasoline cost eighteen cents a gallon. About 140,000 census-takers, or enumerators, fanned out across the country that April. My father-in-law was one of them.

Elmer Liebert walked the Cherokee Park neighborhood in Louisville, Kentucky. He talked of going house to house, filling out his forms as he went. If nobody was home, he had to keep going back until they were available for interview. The 1950 census was the last complete house-to-house canvas. The next census in 1960 was conducted largely by mail. I know mail-in forms are much more efficient, but it seems a shame not to do a physical headcount.

A census form is more than a statistical headcount. It is as though someone has entered every home in America and taken a snapshot in time that tells a story. When Ms. Poldemus filled out that April 1950 census form, Carol Porter was just four months out of her teens. She was coming up on the first anniversary of her graduation from St. Pete High School. My dad was just beginning his career as a plasterer. They were struggling new parents who probably didn’t know much about raising a child. They did such a good job with their four boys I always assumed it was down to their innate wisdom and superior parenting skills. But the census form suggests there may be more to it than that.

Mom, Dad holding me, Grandma, cousin?

Mom, Dad holding me, Grandma, cousin?My mom always said she learned how to be a mother by living with her mother-in-law, Lizzie Porter. My Grandma Porter was born in November 1883. As a teenager she walked from Florida to Texas behind a covered wagon. She lived through two world wars and the Great Depression. She bore thirteen children and faced the burial of several of them. She told me, for example, that before the advent of baby food in jars, mothers would wean their children onto solid foods by chewing the food themselves before providing it to their babies. As a familiar insurance company television commercial says, Grandma Porter knew a thing or two because she’d seen a thing or two.

There is a widely quoted West African proverb, “It takes a village to raise a child”. But my research indicates that the first appearance of the proverb in print may have been in a 1984 interview with author Toni Morrison who said, “it takes a village to raise a child, not one parent, not two parents, but the whole village”.

My mom and dad had a village, and they used it. I was baptized as an infant at Allendale Methodist Church soon after I was born and was reminded of the importance of that on a recent Sunday. My current church, Albany First Methodist, honored the babies who had been born in the past year to our congregation. A half dozen families brought their infants forward and another half dozen were named but not in attendance. Those children had a lot of collective experience in the audience to help their parents raise them.

As we celebrate our parents on Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, it might be useful to remember those who helped them along the way. I only saw my name on that census form because one of my sons was curious and searched the data the day after it came out. He started with his grandpa—my dad—and hit the jackpot. That same son, who lives in Kentucky, asked me to watch two of his children while he was on a business trip and my daughter-in-law was on a school trip with their middle son.

That’s how this retired grandpa found himself in Louisville, Kentucky for a week playing—and losing—endless games of Clue with his nine-year-old grandson and seeing his seventeen-year-old granddaughter off on her first date. I’m not sure how much wisdom was passed along, but it felt right that I should be there. Those children have aunts and uncles, a church family, and other grandparents. But they also have this old man who sure enjoyed his time with them and is proud to be part of their “village”.

May 1, 2022

Cemeteries: Stories Etched in Stone

One of the things I will miss about living in Albany, Georgia is my small-town notoriety. People stop me on the street and in the stores all the time to comment on my articles. One such encounter occurred recently when a gentleman approached me in the shoe store. He had been waiting in his car for his wife when he spotted me walking in. He found me trying on a new pair of Sketchers walking shoes.

The man had, it turned out, seen my articles on Southern plantations and was reminded of a story that played out in Albany over a hundred years ago. He had read about it in the Albany Herald but had loaned the article to someone and never got it back. His memory was a little vague, but he wondered if I was familiar with the story. I was not, but I said I would look into it. I did, and here is what I discovered.

According to the Memoirs of Judge Richard H. Clark, published in 1898, Judge Clark was summoned to Albany Georgia in March 1859 to join the prosecution of the killer of Mr. Joseph Bond. Bond’s story sounds like the tale recalled by the man in the shoe store.

Joseph Bond tombstone, Macon GA

Joseph Bond tombstone, Macon GAJoseph Bond was one of the wealthiest men in middle Georgia before the Civil War. He was the state’s largest cotton grower and most successful planter. It was reported that in 1857, he set a world record with a cotton sale of 2,200 bales for $100,000. Bond was from Macon, but had holdings all over Middle Georgia including, it would appear, in the Albany area at a place he called White Hill Plantation.

According to his contemporaries, Bond was not only a talented farmer and businessman, but he was also a man of the highest character and talent. “He was brave and courageous beyond measure. He could not brook an insult or submit tamely to a wrong.”

When one of Bond’s employees, an overseer by the name of Marshall Brown, beat one of Bond’s slaves nearly to death, Bond fired the man and threatened to whip him if he ever touched one of his slaves again. Brown promptly found a job at a neighboring plantation, which put him in continuing contact with his former boss’s slaves.

Brown, as the story goes, held a grudge against his former employer and found an opportunity to antagonize the man by once again beating one of his slaves. When Bond found out, he immediately rode out to confront Brown and, true to his word, commenced to beat the cruel overseer with a stick. Unfortunately for Joseph Bond, the overseer had the foresight to arm himself. Brown also made sure to have white witnesses present to testify that he was being beaten and acting in self-defense when he pulled out a small pistol and shot and killed his former boss. Joseph Bond was 44 years old. Brown was tried in an Albany courtroom but never charged in the killing.

Joesph Bond’s contemporaries portrayed him as “a kind master”. His slaves were “well clad, well fed, and well cared for”. After his death, his former slaves supposedly spoke of him “with trembling accents of love and gratitude”. I don’t want to be an apologist for slave owners, but Bond was a man of his times, and he did die defending the honor of one of his slaves.

The person who killed Joseph Bond was a cruel, vindictive man who had severely beaten a slave and deliberately shot and killed the man who came to his defense. But he was acting in self-defense. It was a sad story for all involved—especially for any slaves who came under of the lash of Marshall Brown.

The incident is recorded in Judge Clark’s memoir (available at the Dougherty County Public Library). It is also recalled in great detail at the Rose Hill Cemetery blog because, as I discovered, Joseph Bond is buried there.

Macon’s Rose Hill Cemetery is a 50-acre property located on the banks of the Ocmulgee River. It opened in 1840 and boasts the claim-to-fame as being the hangout and artistic inspiration for the Allman Brothers Band during their early years. In fact, Duane and Gregg Allman are buried there. The cemetery was developed outside of the city because the land was less expensive. It was originally designed to be a both a cemetery and a local park.

People who visit Rose Hill Cemetery today might come across the Joseph Bond grave site and be impressed with the memorial’s size and beauty. They might also do a bit of quick math and discover that he was only in his forties when he died. But they will need to inquire further to learn the rest of the story—something I might never had known but for a chance encounter in a shoe store.

Cemeteries are more than just places to lay our loved ones to rest. They are as important to our communities as parks, libraries, and town centers. They are historical archives. When I visited Albany’s Oakview Cemetery, I was impressed with the burial plot of Nelson Tift and his family, but I already knew his story. He was the founder of Albany and the employer of the former slave and bridge builder, Horace King.

I was struck, however, as I explored the tragic story of Joseph Bond that Nelson Tift was in Albany when the incident played out. I wonder if their paths ever crossed. Joseph Bond was murdered near Albany in March 1859, the year after Horace King completed the bridge house and its crossing of the flint River. But if there is a story there, I can find no record of it. Cemeteries only give us the headlines.

Decatur Georgia Cemetery

Decatur Georgia CemeteryAnother intriguing but untold story surrounds a simple, unassuming grave in the cemetery my wife and I recently explored in Decatur, Georgia. The Decatur Cemetery, we discovered, is the oldest burial ground in the Atlanta metropolitan area. The earliest headstones date to the 1820s, predating the City of Atlanta itself by more than a decade. The cemetery is Decatur’s largest downtown greenspace—a quiet park that covers about 58 acres and contains well over 20,000 graves. The landscaping and monuments in the 8-acre Old Section are historically significant and include the graves of local dignitaries, numerous Civil War veterans, and a man named John Hays.

John Hays tombstone

John Hays tombstoneHays was born on November 2, 1751, and he died June 17, 1829. In 1776, Hays would have been 25 years old. He was, according to his marker, a veteran of the Revolutionary War. How did this contemporary of George Washington come to be buried in Decatur Georgia and what was his role in the revolutionary war? Maybe that’s a story for another time.

We can wander among the monuments, headstones, and markers, looking for stories. We can remember heroes and ordinary people, slaves and their owners, people who lived a long life and children who died too young. The stories may be personal or just a collective memory of our community. But cemeteries are a touching reminder of our own mortality because, at the end of the day, whether etched on a stone monument in a cemetery or simply carved into the hearts of loved ones left behind, we will all have an epitaph.

I’m not sure how I would like to be remembered. I like the humorous gravestones, like the one that recalls the famous “I see dead people” line from the 1999 movie The Sixth Sense. One tombstone changes the language of that quote and perhaps gives us a glimpse into the afterlife when it says, “I see dumb people”. Another tombstone says, “Here lies an atheist. All dressed up and no place to go.”

Since I wish to be cremated or composted, I don’t plan to have a tombstone. If I did, I would probably just keep it simple. I like Mel Blanc’s epitaph. The voice of Bugs Bunny and a thousand other cartoon characters has on his tombstone: “That’s All Folks”.

April 20, 2022

Contemplating Tombstones

We had passed it on Interstate-85 before I realized what I had just seen. It was perched on a hill in the middle of the Exit-35 cloverleaf. Traffic was light on a Sunday afternoon and for a moment I thought about turning around to explore it. Who, I wondered, had placed it there and how in the world had someone engineered a highway on-ramp to avoid it? Then, as we drove on and my wife worked her crossword puzzle, my mind really went to work. Why do we need cemeteries in the first place and why do we go to such extraordinary lengths to preserve them?

Cave Hill

Cave HillWhen my wife’s father passed away last year, we buried him in Louisville Kentucky’s Cave Hill Cemetery next to Karen’s mom. Elmer chose the site because it overlooked the property where he grew up. He had played on the cemetery grounds as a boy in the 1930s, and his father had even grazed Liebert Brothers Dairy cattle there before graves began expanding into the area of the property and a wall was erected.

Cave Hill Cemetery is a 300-acre, pre-Civil War era National Cemetery and arboretum. With its lush plantings, scenic lakes, and sweeping vistas, it is more like a public park than a place where the likes of Colonel Sanders and Muhammed Ali are interred. A man by the name of “Big Jim” Porter was buried there in April 1859. I identify with him by more than sharing a name. James D. Porter was also known as the Kentucky Giant. He stood 7 feet 8 inches tall and weighed 300 pounds. I had to snap a photo of his grave site.

The word cemetery comes from the Greek word for “sleeping place”. It is a word that originally applied to places like the Roman catacombs and implies that the land is specifically designated as a burial ground. The term graveyard is often used interchangeably with cemetery, but a graveyard primarily refers to a burial ground within a churchyard.

The modern cemetery probably originated about a thousand years ago in Europe when burials were under the control of the church and could only take place on consecrated church ground. When churchyards began to fill up in the early 1800s, new locations were developed outside the population center. These early cemeteries were professionally designed, elaborately landscaped, and served as the first recreational areas in a time before public parks came into use.

Modern cemeteries offer a space that brings comfort to families as they struggle with their grief while remembering loved ones. They provide a serene environment in which to place flowers and remember the person who has passed.

All four of my grandparents are in Memorial Park Cemetery on 49th Street in St. Petersburg, Florida. I could visit their graves anytime and pause in remembrance. I visit my granddaughter’s grave in Louisville whenever I am there. It is comforting to see her name etched in stone and remember her laughter and sweet disposition.

My parents, on the other hand, chose to be cremated. My brothers and I spread their ashes—half outside their cabin in the mountains of Western North Carolina and half at the St. Petersburg beach that we frequented growing up. They have no headstones, monuments, or markers but for me, sitting in the sand at Pass-A-Grill Beach and reliving my childhood memories is as least as comforting as standing in a cemetery and looking at a granite marker.

I am not opposed to cemeteries, but I don’t plan to have a headstone in one. My wife and I have talked about cremation rather than burial, but cremation seems a needless waste of fossil fuels. That is why we are also investigating more environmentally friendly options.

We could donate our bodies to science, an option that might contribute to the advancement of science and medicine. I wonder what name those med-students would give to my long, skinny cadaver. The name that comes to my mind is the tall, cadaverous Addams Family butler “Lurch”—a nickname that was hung on me in high school.

We briefly considered something called Alkaline Hydrolysis—a water-based dissolution process that uses heat, pressure, and alkali chemicals to gently break a human body down into chemical compounds. But as people who love nature and the outdoors, there are some even more attractive ways to become one with the earth.

We could be buried in something called a mushroom suit—a natural burial shroud made from biodegradable mushrooms and microorganisms. These organic materials aid in body decomposition and neutralize toxins, releasing nutrients into the surrounding environment and promoting new growth. Or we might consider human composting, a process that uses “organic reduction” to convert a human body into soil. It sounds almost too simple. The body is covered with natural materials such as straw and wood chips and left to decay. The resulting microbial activity breaks it down into clean, odorless soil that’s free of pollutants and toxins. We have been composting organic material for our garden for years. I kind of like the idea that someone will haul my worn-out carcass to the backyard and let it turn back into soil for their garden.

The cemetery inside the I-85 cloverleaf at exit 35 is the John Coggin Meadows Cemetery. Meadows apparently bought the land on which the graves are located in 1838 for $500.00. The property in Coweta County was passed down through the family and eventually sold many times, but always with the exception of a small plot at one corner of the lot—a section that came to be known as “the Old Meadows Cemetery”.

When the Department of Transportation was planning the right of way for Interstate 85, surviving members of the Meadows Family objected to relocating the Cemetery. The DOT agreed to preserve it and, judging by the fresh flowers and new grave sites, it is still sacred ground to the family. But the garden-like atmosphere left when the Interstate highway arrived.

The Easter season and the empty tomb seems an appropriate time to consider our own mortality. Honoring and remembering the departed is an important part of our culture. But cemeteries take up space. And someday when all who know us are gone, what will be the purpose? I wonder about our tenacious insistence on having an “eternal” resting place, as though that plot of ground is where we will reside for eternity. A hundred years from now, nobody is going to be looking for my grave, anyway. The only problem might be that someone in Louisville Kentucky—where I lived for a while—might visit Cave Hill Cemetery and mistake me for another James D. Porter. He died ninety years before I was born, and he was known as “the Kentucky Giant”. I’m a foot shorter and a hundred pounds lighter than he was, and after a lifetime of being teased about my height, I don’t particularly want to spend eternity being known as a “giant”.

April 4, 2022

Our Final Spring Fling

Its Spring. The first official day was Sunday, March 20th but there are plenty of other signs. The azaleas, redbuds, and dogwoods are blooming. The first hummingbirds are back at my feeder. And the Masters golf tournament begins Thursday, April 7th.

On the downside, I am cleaning up the lawn mower in anticipation of mowing season. We are continually wiping the layer of pollen that covers every surface on our screen porch. And we are packing boxes in preparation for moving day.

Another sign is that the Dougherty County school system is on Spring break the week of April 4th. It is our final school spring break before my wife retires. Since she works in the school system, we have always built our year of travel around the various school breaks—fall, Christmas, spring, and summer. It seems a generous amount of time off except when you consider we have only been able to travel whenever the rest of the world is traveling. Airports are packed. Attractions are full. And don’t even get me started on the highways.

Spring break has always been a welcome respite for us. In the past, we have spent spring breaks at the beach but in recent years, we have travelled to visit family in the North Carolina mountains or in Louisville, Kentucky. But all of that is about to change. As retirees, we are expecting every day to be a weekend, and every weekend to be a “break”. Spring break will be a time NOT to travel.

I don’t often praise Yankees and how they do things up north. But one thing they have over us is how they celebrate spring. They have no choice. It is sudden, it’s dramatic, and it’s over in a few weeks.

We lived in South Dakota and Northern Ohio for a dozen years and believe me, those folks know how to celebrate spring. When we lived up there, winter meant a set of snow tires on the car and a survival kit with thermal blanket, candles, matches, and food in the trunk. Snow shovels, snow blowers, and bags of ice-melting salt stood at the ready. Our wardrobe included long underwear; caps, hats, and earmuffs; heavy socks, snow boots, and ice skates; and coats, parkas, and scarves. The parks near our house flooded flat areas and turned them into outdoor ice-skating rinks from November till March. You can only do that when it doesn’t get much above freezing, even on the warmest of days.

So in the North, after four or five months of bitter cold days, frigid nights, and snow-covered ground, the need to get outdoors seemed almost pathological. The grass seemed especially green, the flowers remarkably bright, and the air refreshingly crisp. On a Northern Spring weekend, we spread blankets on lush park grounds, planted flowers around the house, and packed the neighborhood swimming pools. Just being outside was a luxury, especially without a coat, mittens or snow boots. The air was no longer hazardous to our health. Mowing grass was a pleasure not a chore.

Spring in the South is less abrupt. It is more like a gentle shift from mostly chilly to mostly mild. It is a time for dinner on the screen porch, a drive in the car with the sunroof open, and sleeping with the bedroom windows open. Soon, it will be too hot for any of these.

This spring, however, feels a little different to me. While it is great to have the mask off and enjoy seeing people’s smiles, it somehow feels like crisis times are not over. COVID variants are still popping up, the political climate is more fractured than ever, and the war in Ukraine grinds cruelly on.

But springtime is a season of hope and rebirth, so I am going to look forward to what it has to offer. I’m going to make the best of it. Maybe I’ll attend Chehaw’s Party for the Planet or the Flint RiverQuarium’s Wild Affair. Perhaps I should take a class at the Albany Museum of Art or just relax at Pretoria Fields on their trivia night. And as for Spring Break, I won’t be worried about crowded airports or clogged highways. Until we make the move this summer, I have two yards to mow, two mortgages to pay, and endless boxes to pack.

March 25, 2022

Living Life in the Fast Lane

People in South Georgia give me the “side-eye” when I tell them I am moving to Atlanta.

“The traffic up there is terrible,” they somberly inform me with an are-you-out-of-your-mind kind of look.

“Oh, really!” the bubble of sarcasm above my head says, “I hadn’t noticed.”

What I actually say is, “I know that, but since I will be retired, I don’t much care.”

When I drove the mule-drawn wagon on a quail hunting plantation, I was reminded of the slow pace of the lives of our ancestors. I wondered what it would be like for me to drive to work every morning on my wagon. I wouldn’t need to worry about traffic jams or speed traps.

My mules pulled an old-fashioned wagon with a heavy wooden body and tall, spoked (albeit rubber-tired) wheels. It was not a stretch to imagine a time when this type of transportation was the norm. My 200-mile, three-hour drive to Atlanta, according to Google maps, would take more than two days on a wagon. Image needing to stop at the Motel 6 halfway to Atlanta!

At the end of every hunt, we had a fifteen- or twenty-minute ride back to the house. The pointers were back in the wagon and the retriever was lying on the seat beside me as I followed the horse riders. The only sound was the jingle of the mule harnesses, the conversation of the guests, and the occasional bobwhite quail whistling in the tall grass. The pace was slow enough for a person to walk but I never heard a guest complain about the length of our ride. In fact, people often remarked on how peaceful it was and how they could feel their blood pressure going down—a sensation that is unlikely when we travel today.

We drive to Atlanta twice a month to work on the new house. It is a pleasant drive up highway 280 to Columbus where we get on I-185 then I-85 and on to Atlanta. It is usually smooth sailing until we get near our destination, because the closer we get to Atlanta the faster people drive. We are bumper to bumper by the time we get on the I-285 beltway, and I struggle to keep up with the dense traffic. Even going more than 70 MPH, cars pass me like I am standing still. They cut across multiple lanes of traffic, weave between speeding cars and trucks, and dart in front of me to get to the nearest exit. On my last trip, I saw a car drive along the right-hand emergency pull-off lane to pass multiple cars who weren’t going fast enough. What, I wonder, is the hurry?

There are only two things that might make a driver slow down. One is when eight lanes of traffic comes to a complete stop. The other I see on those rare occasions when I am going fast enough to pass someone. Invariably they are not watching the road. They have one hand on the wheel and their eyes glued to a cell phone as they drift from lane to lane.

Now, I like to drive fast. That is why I usually set my cruise control when I am on the open road. Otherwise I will find myself driving over the speed limit when I round the bend and see that highway patrol vehicle parked in the median. But there is no cruise-control on the Atlanta freeways. You are either going way too slow in the middle lane or thrust into the slipstream of cars and trucks with your hands at ten and two on the steering wheel, your speedometer in the mid-80s, and your heart thumping in your chest.

And then there are the fools who drive too fast for conditions. One recent Sunday morning, I was on the Stone Mountain Freeway on my way to have a tire repaired. It was raining and I was driving on the spare tire. I struggled along at 55 MPH so, as usual, cars were passing me right and left. Suddenly there was a white work van passing me on my left—but it was traveling backwards. I did a double take as the van slowed down and faded from view. I glanced in my rearview mirror. Somebody must have hydroplaned because cars were spinning out on the rain-slick road behind me. A car veered into the median and another careened off the road to the right as the white van came to a stop in the middle of the highway.

As I viewed the chaos behind me, I slowed a little and relaxed in my seat. For the moment I was alone on the road, so I turned up the radio and recalled my time on the wagon when the mules were in harness, a dog rested on my lap, and life was moving at a peaceful pace. In the blink of an eye, I had gone from adrenaline-fueled stress on the roadway to absolute calm. Welcome to life in the big city.