J.D. Porter's Blog, page 5

March 8, 2022

War Dogs of Ukraine

Whenever I write an article for the Albany Herald, I follow it up by posting it on my website as a blog. That pushes it out to a broader audience and allows me to track how many times it is viewed.

One of my favorite articles was one I did last year under the title “The Dogs of War”. It was about how we humans have been using dogs in battle for centuries. It focused on dogs like the German shepherd, the Doberman pinscher, and more recently, the Belgian Malinois. I suggested that we owe them a debt of gratitude for their service and their sacrifice. The article ran in the Albany Herald in May 2021, and I posted my blog on June 1st. It has been a popular article ever since I posted it, but beginning on Feb 21, 2022, activity spiked. Why, I wondered, is it getting so much attention recently?

My wife suggested it might be because of the Google search words, “dogs” and “war” and the recent news about people in Ukraine fleeing the war and taking their pets with them. I did some digging and it turns out, as usual, she was right.

One report from the Times of India, for example, is about software engineering student, Rishabh Kaushik. He apparently criticized the Indian embassy, the Animal Quarantine and Certification Service (AQCS) and the Indira Gandhi International Airport for making it “impossible” to fly his dog home with him to India. Kaushik adopted his dog, a mixed breed he named Maliboo, from a local resident who rescued the dog from the streets as a puppy. Kaushik’s family has already left Ukraine, but he stayed behind in hopes of gathering the necessary paperwork for him to travel with his dog.

More favorable reports are coming out of the neighboring countries of Romania, Poland, and Hungary. Officials there are waiving paperwork and relaxing requirements for vaccinations, microchips, and other documents. They are allowing all types of pets to enter their countries as “refugees”. Television news reporters frequently interview refugees who are clutching their dogs.

I feel for the people of Ukraine and admire their spirit. I like to think that if some country was invading my neighborhood, I would pull the shotgun from my closet and stand in the street with my neighbors to fight. But what about our neighborhood dogs. They would surely be freaked out by the noise and chaos.

When I wrote about “The Dogs of War”, I was referring to certain breeds of dogs that are trained for combat. They are conditioned to the sights, sounds, and smells in the same way hunting dogs, horses, and mules are conditioned to the blast of a nearby shotgun. I have seen young cockers on the hunting wagon cowering when a shotgun is discharged. Many of them get over their fear. Some never do. They get retired to some family’s home where they will spend their days sniffing around the backyard and sleeping on a dog bed next to the fireplace.

You can, I believe, tell a lot about the character of people by the way they treat their animals. I admire the people of Ukraine for the way they are standing up to the mighty Russian army with personal firearms and Molotov cocktails. But I also admire the fact that they are not abandoning their pets. They are evacuating the women and children while the men stay to fight, but the women and children are saying we are not leaving without our pets.

If I was forced to defend my country, I think I would keep my dogs close by and we would fight together. Who knows, maybe Libby the goofy golden retriever would turn into a true war dog. Maybe she would share my anger at having our home invaded. But I wonder if either one of us would be as courageous as that software engineering student in Ukraine.

“I decided that if my dog can’t leave, I won’t either,” Rishabh Kaushik said, according to The Times of India. “I know that there is risk in staying on, but I can’t just abandon him. Who will take care of him if I go?”

February 24, 2022

Horace King – The Man

The Bridge House, Albany GA

The Bridge House, Albany GAI can’t imagine a more unlikely pair of business partners. Horace King, the hard-headed former slave who walked out on his last project because of business differences and Nelson Tift, the hard-driving businessman who was, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, “committed wholly to slave society”. King was probably still irritated at white people trying to take advantage of him on his last job. Tift was a slave owner who also came to the Albany bridge project with a thorn in his side. He was paying for the bridge out of his own pocket after he had failed to interest either the city or the county in the idea. (Oh, to be a fly on the wall at their first meeting!)

Born in 1810 to a Connecticut mercantile family, Nelson Tift followed his father into business and headed south. He moved around for a few years before he settled in Albany, Georgia in October 1836. Tift’s business acumen saw him speculating in land, operating a dry goods store and several mills, and acquiring the rights to operate a ferry and, later, a toll bridge across the Flint River.

It is worth noting that, even though he used the services of Horace King, a freed slave, Tift was deeply committed to the principles of slavery. He owned slaves himself and as a member of the Georgia legislature, he supported the reopening of the international slave trade (which had been prohibited by law since 1808) as a way to encourage ownership of enslaved people to all white Georgians. He died a wealthy man in 1891.

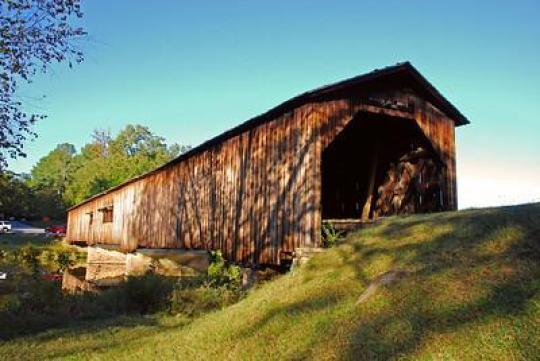

Watson Mill Bridge

Watson Mill BridgeLittle is apparently known about Horace King’s bridge across the Flint River, except that it was completed in 1858. Judging by the location of the Bridge House and its corresponding bank across the river, it must have been at least 300 feet across. A comparable bridge can be seen at Watson Mill Bridge State Park near Comer, Georgia. Watson Mill Bridge claims to be the longest covered bridge in the state, spanning 229 feet across. It was built in 1885, the year of his King’s death, by Horace King’s oldest son, Washington. He, of course, used Ithiel Town’s Lattice Truss and tree-nail system. At one time, according to the Georgia State Parks website, Georgia had more than two-hundred covered bridges; today, fewer than twenty remain. Most of them gave way to fire, flood, or the ravages of time on untreated wood.

After he left Albany, Horace King spent the rest of his long life as a prosperous builder and businessman. He died on May 28, 1885, at the age of 78, but his legacy goes far beyond his buildings. When his former owner, John Godwin died in 1859, his estate was insolvent. As a testimony to how much the Godwin children honored Horace King, they formally recorded in the Russell County Courthouse that “Horace King is duly emancipated and freed from all claims held by us.” They knew that as a former slave, King could be held accountable for their father’s debts.

King remained close to the Godwin family, helping Godwin’s son run the failing family business. In addition, King quietly provided for his former master’s family. According to one of King’s contemporaries, Godwin’s children “became [King’s] wards at his own option.”

John Godwin grave

John Godwin graveBut perhaps the most telling legacy of Horace King is a monument he purchased and erected on the grave of his former master. The inscription reads:

John Godwin Born Oct. 17, 1798. Died Feb. 26, 1859. This stone was placed here by Horace King, in lasting remembrance of the love and gratitude he felt for his lost friend and former master.

The monument bears the Masonic emblem, the square and compasses, which marks Godwin as a Mason. In fact, the monument is presented from one Mason to another.

Faye Gibbons notes in her 2002 book, Horace King, Bridges to Freedom, that two years after Godwin’s death, King was in Ohio visiting friends and seeking to join the Masons—something that was not allowed for a black man in the South. After he became a Mason, King obviously took to heart its principles of brotherly love, relief, and truth and he would have been especially concerned about the Masonic care of widows and orphans—even those of his former slave master.

I am fascinated by the character and resolve of this former slave, turned craftsman, turned business owner. Following the Civil War, King served two terms in the Alabama Legislature. He brought all five of his children—four sons and one daughter—into the business and formed the King Brothers Bridge Company. They went on to build courthouses, mills, public buildings, and, of course, hundreds of bridges. All the while, King cared for and supported the children of the man who once owned him.

Today, we may remember Horace King as what his contemporary Robert Jemison, called “the best practicing bridge builder in the South.” But to remember King simply as a builder of bridges sells the man far short. His greatest achievements may have been simply in his humanity.

February 16, 2022

Horace King

Part 1 – The Bridge Builder

As a white child of the Jim Crow South, I probably have little right to opine on Black greatness. But during Black History Month, I keep thinking about someone I have admired since I learned his story when I moved to Albany. He is seldom mentioned in the same breath as the likes of Rosa Parks or Martin Luther King. But he and I are kindred spirits even though he was black, and we were born nearly one hundred fifty years apart.

We both became Masons when we lived in Ohio—he in Oberlin and me a few miles to the West in Toledo. We both love to build things—I build furniture and he built bridges. And we both love our mules. He once sued the Federal government to try to recover some mules the Union Army “requisitioned” from him during the Civil War.

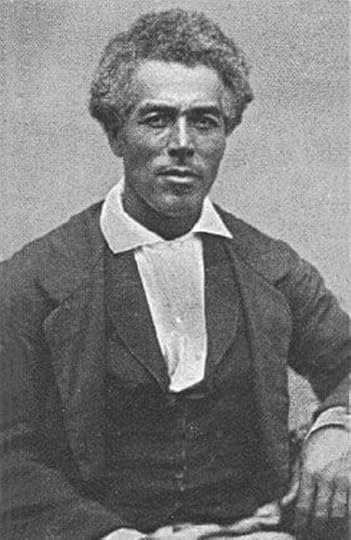

Horace King

Horace KingAccording to the Alabama Heritage website of the University of Alabama, Horace King was born in South Carolina on September 8, 1807. Little is known of his early life, but he appears to have acquired considerable knowledge and skill as a master carpenter and bridge builder. He was a type of slave known as a craftsman.

Craftsman slaves had specialized and highly sought-after skills. They were carpenters, blacksmiths, and teamsters and they were often hired out by their owners to make money. Usually, their earnings went to the master, but some craftsmen were allowed to keep some of their money and perhaps even work unsupervised. A few even set their own wages and arrange their own jobs. Horace King became one of these.

He was purchased when in his early 20s by John Godwin, the son of a prominent South Carolina businessman. Godwin was a builder who learned the bridge-building innovations of Connecticut architect Ithiel Town. Town’s design, which he had patented in 1820, was called the “Town Lattice Truss”. It was an entirely new system of wooden framework that could be erected using inexpensive common sawmill lumber and the labor of any carpenter’s gang.

The system used upright, two-by-ten, rough-cut planks along the walls of the bridge that were set at an angle in a crisscross pattern. The boards were fastened where they crossed with a couple of two-inch diameter, wooden pegs called “tree nails”. This allowed a span of a little over a hundred feet before the structure needed support from below, usually in the form of a stone tower or pier. A roof added structure to the bridge and protected the wooden framework from rot. Much of the assembly occurred in a field nearby where the wall boards could be fastened together while flat on the ground. The wall sections were then transported to the job site and erected—an early example of prefab construction.

It is likely that John Godwin and his slave, Horace King, became acquainted with Town’s innovative truss design at a construction site in South Carolina because both Godwin and King were familiar with the Town Lattice Truss before they left South Carolina for Columbus, Georgia in 1832.

John Godwin, doing business as John Godwin, Bridge Builder, had submitted a bid to construct the first public bridge over the Chattahoochee River. His bid was accepted, and Godwin and King began work in May 1832. In July they advertised in the Columbus Enquirer for stone masons to work on the piers of the bridge and by August the project was well underway. When completed in 1833, the nine-hundred-foot-long covered bridge earned Godwin and King reputations as master bridge builders and work began to flow their way.

Apparently, from the beginning of their relationship, Horace King was more of a junior partner in Godwin’s company than a slave. Godwin developed proposals and King supervised construction. In addition to building bridges, King spent much of the 1830s and 1840s working on the buildings and houses that the Godwin firm built around Columbus and Girard (now Phenix City), Alabama, where they had taken up residence. King’s ability to supervise massive construction projects and to elicit superior workmanship from mixed gangs of laborers, both slave and free, impressed some of the most successful businessmen in the South.

One of these men was Robert Jemison, Jr., of Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Jemison was a lawyer and state senator who owned a large and well-organized network of interrelated businesses that included a stagecoach line, a turnpike and bridge company, and extensive sawmill operations. In the early 1840s, Jemison began contracting with Godwin for bridges in Alabama. Horace King supervised the construction. After several joint ventures with Godwin and King, Jemison wrote a testimonial to Godwin in 1845 that praised King’s “style and dispatch” and “the impressive manner in which [King] has conducted himself.”

As King’s fortunes rose, however, those of his master declined. By 1846 Godwin had suffered a series of financial setbacks. Realizing that King could be taken from him to settle debts with his creditors, Godwin arranged with Robert Jemison to petition the Alabama General Assembly for King’s release from slavery. After Godwin posted the required $1,000 bond Jemison succeeded, and on February 3, 1846, Horace King became a free man.

A few years later, King was contracted to build a bridge across the Oconee River in Milledgeville, Georgia. He set up his prefab operation and began the project, but a disagreement arose over payment for the bridge. When King and his employers were unable to come to terms, what happened next seems extraordinary to me and is, perhaps, an indication of Kings character and resolve.

Horace King, a black man doing business in the pre-Civil War South, walked out on his white employers. He loaded the timbers, lattices, and other bridge materials onto railroad flatcars and moved them to another project. An enterprising, South Georgia businessman had heard all about Horace King and was anxious to acquire his services. The man was Nelson Tift, who wanted to build a bridge across the Flint River in Albany, Georgia.

February 9, 2022

Part 4: The Tortoise and The Billionaire

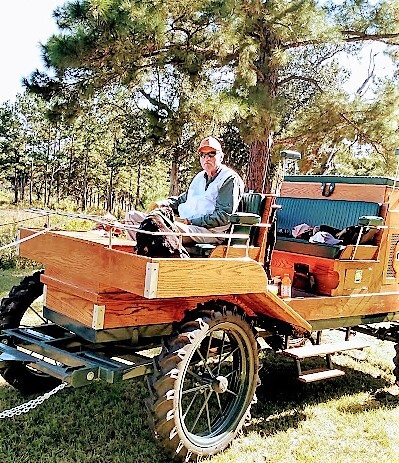

It was one of those moments that passes almost without a thought. We’ve all done it a thousand times. Like when we are driving along in our car and suddenly we arrive at our destination without any recollection of how we got there. For me, it happened on the first quail hunt of the season with my employer and his family and friends. The mules were behaving nicely on this splendid, warm October morning, so I was driving the wagon along the trail watching where I was going but allowing my mind to wander.

The two-thousand-acre property where we were hunting is a few miles Northeast of Tallahassee, Florida. It was once called Chemonie Plantation. Its history is said to date back to the early 1800s after President Andrew Jackson forced-out the Seminole Indians. Chemonie began as a slave-holding plantation that grew cotton, corn, and sugarcane. It thrived until the Civil War freed the slaves. When the owners went bust, the fields turned back into their natural scrub.

This is when the second wave of owners swept into South Georgia and North Florida, drawn to the huge population of quail in the grasslands of these plantations. They had no interest in having slaves work the cotton fields. They were people of wealth—people who invented things like shoe polish or paint cans or shotgun shells. America was in the midst of the industrial revolution so oil barons, automobile dealers, and company CEOs had plenty of disposable income.

They bought property and turned it into prime hunting lands that soon became highly sought after by bird hunters worldwide. Chemonie has been sold and divided several times and now operates under another name. The current owners of the property are remarkably similar to the people who first started the post-war hunting Plantations nearly 150 years ago. They enjoy being outdoors. They love hunting quail. And they are happy to put their considerable resources to work preserving quail habitat. It is where my wagon driving career continued after Gillionville Plantation in Albany, Georgia ceased operation and where I finally retired from wagon driving at the end of 2021.

One of the challenges of driving a mule wagon through the woods is “road hazards” like logs, stumps, and gopher holes. They can wreck an expensive, custom-built wagon and ruin a hunt. As I bounced along the path deep in thought I guided the mules to the right with a gentle tug on the reins. I had noticed a gopher tortoise burrow at the edge of the road. It was unmistakable—its flat floor and domed arch perfectly matching the shell of what must have been a large tortoise. The yellow sand that had been excavated out of the hole was spread halfway across the cart-path.

As we rumbled along, it took me a few minutes to register what I had just witnessed. Nobody on my wagon commented on the obvious and positive sign of gopher tortoise activity and the six people on horseback ahead of me took no notice either. If it had been a deer, a turkey, or even a hog they would have been excited. I was the only person who was pleased to see signs of a tortoise and was left to wonder how many other tortoise burrows were spread around this property.

Two-thousand-acres is a lot of space and I spent most of my wagon-driving days lost in its vastness. There were few signs of the civilization that surrounded us. It was home to countless critters, but the gopher tortoise is special. It was designated Georgia’s State Reptile in 1989 and is now listed as “threatened”. It is considered a keystone species in the rapidly disappearing longleaf pine/wiregrass ecosystem because its burrows provide shelter for hundreds of other species living in their habitat. That is why I was silently disappointed that nobody—including the owners of the property—took notice.

The family I worked for as a wagon driver fit the 21st Century profile of the quail hunting pioneers. I don’t talk about my employers out of respect for their privacy, but their story and contribution to conservation is too important to ignore. Most quail hunting properties utilize jeeps and ATVs to move hunters around the property. It takes deep pockets to hunt with horses, mules, and wagons. My employers wanted an experience that was closer to the land. They hired talented people, built quality facilities for the dogs and hoofed stock, and they began a process of burning the property on a regular basis.

If they had wanted to add to their already considerable wealth, they might have been better served to develop the property. We were fifteen minutes off of I-10, a few miles from downtown Tallahassee. It was prime real estate and much of the surrounding area has already been turned into subdivisions and commercial property. I had seen the process unfold in the woods behind my boyhood home in St. Petersburg, Florida.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the Florida woods where I grew up is called pine flatwoods and it is said to represent the most extensive type of terrestrial ecosystem in Florida. Approximately fifty percent of Central Florida’s natural land area is pine flatwoods—forests that are dominated by Southern slash pine and interspersed with an understory of saw palmetto and mixed grasses. And, like the longleaf pine savanna of South Georgia, regular burning is required to maintain an open plant community. This is probably the habitat that gave Herbert Stoddard the idea to burn the quail hunting plantations. I watched the acres of pine flatwoods where my brothers and I roamed as boys get swallowed up in development until it was one giant subdivision of housing. The deer, fox squirrels, rabbits, tortoises, and quail disappeared.

This is what struck me as we trundled past this lone gopher tortoise burrow on a pleasant October morning—the image of my childhood woods now being covered by a subdivision. Even though the owners of this property can ride past an obvious tortoise burrow without noticing, these plantation owners are preserving that tortoise without realizing it. I don’t mind that the property is owned by rich people who love to shoot birds. I also don’t care that it is private property and not a park that is open to the public. It may even be better this way.

Just before lunchtime, I came to understand just how fortunate the animals on this plantation were. We had just come up a rise and crested a hill. There spread out before us was a large lake nestled in the rolling hills. Its blue waters sparkled in the late morning sun and a bald eagle soared overhead.

We had been passing through beautiful countryside all morning and I had been listening to the conversations on my wagon. I knew what one of my passengers was going to say, because I saw it myself. As we glided to a stop to honor the dogs on-point, the man stood up from his seat behind me, pointed to the lake, and exclaimed to his seatmate, “My God, this would make a beautiful golf hole.”

Plantations have been preserving irreplaceable wildlife habitat for more than a hundred years and I hope they will continue their stewardship. Thank goodness my employers were hunters and not golfers or property developers!

February 2, 2022

Plantations, Part 3: The Fire Bird

I grew up thinking fire was the enemy of the forest. It killed trees, injured animals, and spawned a ruined blackened landscape. I saw the horrors of a forest fire as a child when I watched the Walt Disney classic, Bambi. It wasn’t until I took over management of Chehaw Park that I learned the truth about the benefits of fire from our Natural Resources Manager, Ben Kirkland.

I assumed it was Smokey Bear and the U. S. Forest Service that had steered me wrong. “Only YOU can prevent forest fires!” But in truth, the problem was much older than Smokey Bear—who came on the scene in the 1940s—and it was plantation owners who shattered a dangerous myth and helped save the Southern forests.

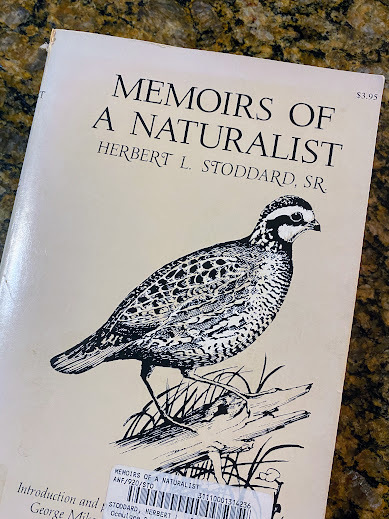

In the early 1920s, plantation owners around Thomasville, Georgia began to notice a serious decline in quail populations and feared that the birds might become extinct in the region. They recognized the need for a scientific study of the bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) in hopes of reversing the decline. So, in the fall of 1922 they reached out to Herbert L. Stoddard, a 33-year-old naturalist, ornithologist, and taxidermist who ran the bird department at the Milwaukee Public Museum.

To finance the quail research project, plantation owners organized. They dug into their own pockets, reached out to friends, and raised the necessary funds. By fall 1923, Stoddard was stalking the woods between Thomasville and Tallahassee trapping quail, studying what they ate, and what ate them. He had no college degree—no formal education or scientific training. But, as it turned out, that is what allowed him to discover the real problem that faced the bobwhite quail and the habitat they needed to survive.

Stoddard was from the North but had spent much of his boyhood in Central Florida. He was well familiar with the practice of Florida cattlemen and Native Americans who intentionally set fire to their land. One of his first recommendations was that that the effects of burning might be important to the Thomasville quail studies.

“The bobwhite,” Stoddard noted in his 1969 book, Memoirs of a Naturalist, “might properly be called the ‘fire bird’ so closely is it linked ecologically with fire in the coastal pinelands.”

He knew that quail thrive in the aftermath of fire. He told the plantation owners that quail need the perennial legumes and grasses that sprout after fire. Excluding fire allowed the buildup of what he called “rough” habitat. The thick cover of shrubs and small hardwood trees favored rodents—especially cotton rats—which attracted predators like foxes, birds of prey, and the huge abundant diamondback rattlesnakes he encountered when he first moved to Georgia. It was exactly the wrong habitat for bobwhite quail. His clients apparently bought his argument. Others were skeptical at best. Some were downright hostile.

Stoddard was classified by the professional forestry community as an enemy of the forests because he not only suggested Southern forests could be burned but insisted they should be burned. He introduced the concept of “controlled burning” or “prescribed fire” to maintain natural vegetation and wildlife.

In those days U. S. Forest Service was against any use of fire for land management purpose even in in the southeast where fire was a natural process. American forestry, Stoddard noted, was rooted in European (especially German) forestry practices where there were no fire-type forests. In addition, all U. S. forestry schools in those days were located in the north where forestry classes and textbooks did not acknowledge fire-type forests. Forestry experts assumed fire would have a disastrous effect on game and wildlife management. They pointed to uncontrolled wildfires in the western mountains and in the northern forests. At the American Forestry Association meeting in February 1929, Stoddard presented the chapter on fire from his soon-to-be-published book The Bobwhite Quail: Its Habits, Preservation, and Increase to the assembly. He was greeted, he recalled, with “great hostility”.

The Forest Service eventually came around and today burning the Southern pine forests is accepted practice. The Georgia Forestry Commission and the Georgia Prescribed Fire Council say prescribed fire “is a safe way to apply a natural process, ensure ecosystem health and reduce wildfire risks”. They note that habitats across the state have evolved with fire and that the strategic application of fire mimics this natural cycle. Even Smokey Bear has updated his message to “Only You Can Prevent Wildfires” in an attempt to clarify that he is promoting the prevention of unplanned outdoor fires, not prescribed burns.

At most modern plantations, prescribed fire is the primary land management tool for managing thousands of acres of forest and wildlife resources. At Robert W. Woodruff’s Ichauway Plantation, for example, I saw fire used on a massive scale during my first visit there in the fall of 2004. According to the website of the Jones Center at Ichauway, healthy longleaf pine forests depend on frequent fire. In the absence of fire, longleaf pine forests shift to hardwood dominated forests over time. The unique plants and animals found in longleaf pine forests have adapted to frequent fire and depend on it to maintain their preferred habitat structure.

The pine forests of the Southeastern United States are thought to have once covered fifty percent of the land across thousands of miles of nine states from Virginia to Texas. The late biologist E. O. Wilson once identified twelve of the best places on earth to see a living natural environment. He placed our longleaf pine savanna in the same category as the Amazon rainforest and the Serengeti grasslands.

A hundred years ago, plantation owners brought in a maverick, Yankee forester who convinced them to go against all of the “experts” and burn their property. They bought his radical concept, and they are still burning today. Without the stewardship of these wealthy landlords and the radical ideas of Herbert Stoddard, Southwest Georgia probably wouldn’t have thousands of acres of one of the world’s most important natural ecosystems—the southern pine forest.

January 29, 2022

Plantation ‘carpetbaggers’ became pioneers in game management

We called them “carpetbaggers”—people from the North who came south after the Civil War to profit from Reconstruction. The rest of the nation knew them as “Robber Barons”, but I doubt anyone said that to their faces. Folks probably just called them by their names—Goodyear, Vanderbilt, and Firestone. In the late 1800s, when the railroad reached Thomasville, Georgia, these well-to-do pleasure seekers from up north flocked there to breathe the healing, pine-scented air and enjoy the traditional southern pastimes of hunting, fishing, and active socializing. They purchased thousands of acres of property—mostly failed cotton plantations—and began the transition of plantation culture from slave-supported agriculture to hunting and land management.

One of the first northerners to purchase a plantation specifically for hunting purposes was Dr. John T. Metcalfe, a New York physician. He purchased a property near Thomasville, Georgia known as Seward Plantation in January 1883. Metcalfe eventually sold this property and purchased Susina Plantation in 1887. Metcalfe was an early booster of the new southern plantation culture. He wrote a letter published in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal which praised the hunting and fishing saying, “to the angler and the sportsman, Thomas County is paradise . . . I wish more northern doctors knew what I know. I have just bought me a ranch of some 1,600 acres on account of the excellent shooting and fishing obtainable from it. “

The hunting that Dr. Metcalfe so enthusiastically enjoyed had become possible in the 1870s and 1880s, because of two significant developments. First, the breech-loading, hammerless, self-ejecting, choke-bored shotgun came into use. Also during this period, sporting dogs were developed as a breed. According to the American Kennel Club, America’s first bird dog field trial was held in 1874 near Memphis, Tennessee. These early trials included English pointers and a variety of setters including English, Gordon, and Irish. Those who could afford fine guns and well-trained bird dogs were ready to take to the woods in search of bobwhite quail, and the piney woods of Southwest Georgia were the perfect spot to do so.

In 1891, Dr. Metcalfe sold Susina Plantation, then 3,200 acres, to Alfred H. Mason, the wealthy son of the man who had founded a successful shoe polish business in Philadelphia. A few years later, John W. Masury—a New Yorker who is reported to have developed paint cans—purchased approximately 1,500 acres and named his property Cleveland Park. This was a telling name because it was people from Cleveland, Ohio with Standard Oil connections who eventually came to own most of the plantation properties in the Thomasville-Tallahassee region.

Howard Hanna and Mark Hanna, for example, had made large fortunes as early members of the Standard Oil Trust. The Hannas and their friends, relatives, and descendants were among the first plantation owners in the Thomasville area. They purchased Elsoma Plantation in 1891, Melrose Plantation in 1891, and Pebble Hill Plantation in 1896. From these beginnings, the Hanna family holdings expanded until they owned nearly two dozen plantations encompassing over 70,000 acres of land. Another nineteen plantations encompassing an additional 78,000 acres were owned by Cleveland area friends and business associates of the Hannas.

Northerners did not begin to acquire quail plantations in Albany, Georgia and surrounding areas until the 1920s—four decades after they had descended on the Thomasville-Tallahassee region. That was because landowners in Thomasville were not about to part with any of their land. Instead, they steered their friends, family, and business associates to the failed cotton plantations farther north.

Walter C. White, for example, was the owner of the White Motor company of Cleveland, Ohio. White Motors had provided trucks to the U. S. Army during World War I and had grown into one of the nation’s largest manufacturers of trucks and buses. White and his company vice president, Robert W. Woodruff—who was vice president of White Motors before becoming president of Coca Cola—were both members of a hunting club which owned the large Norias Plantation near Tallahassee, Florida. In 1929, they sold their interest in Norias and purchased nearly 30,000 acres of property in Baker County, Georgia called Ichauway Plantation. They were avid outdoorsmen who recognized the unique natural characteristics of the land and intended to preserve one of the most extensive tracts of longleaf pine and wiregrass in the United States for quail hunting.

A few miles up Highway 91 near Albany, John M. Olin was developing Nilo (Olin spelled backward) Plantation. Olin had joined his father’s business when he graduated from Cornell University as a chemical engineer in 1913. The Olins owned the Equitable Powder Company in East Alton, Illinois, which became Western Cartridge. They purchased Winchester when that company went bankrupt in 1931 and John Olin went on to develop many new firearms-related products for Winchester. One of his best known—the Super-X shotgun shell—is in my gun cabinet today.

But Olin’s most significant legacy may be his conservation work at Nilo Plantation. Olin is said to have inspired author and conservationist Aldo Leopold—best known for his 1949 classic, A Sand County Almanac—to write his 1933 book, Game Management, the gold standard used by modern conservationists. And he also hired Herbert Stoddard, the famous Georgia quail biologist, to advise him on quail management practices on Nilo.

I saw first-hand from my perch on the wagon how wealthy northerners like John Olin have shaped the land in Southwest Georgia and North Florida. Their passion for hunting and conservation has helped preserve thousands of acres of wildlife habitat. Perhaps carpetbagger is not the right name for people who converted failed cotton plantations into quail hunting plantations. And perhaps the word plantation needs to revert to its original meaning as a property where crops are grown, crops like the longleaf pine trees that are sprouting at Robert Woodruff’s Ichauway Plantation.

The legacy of quail plantation pioneers like Olin and Woodruff continues today at places like the Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center at Ichauway Plantation. Jones Center research scientists study forest and wildlife management. It is where I had my introduction to the South Georgia quail hunt in 2004. We’ll take a closer look at the work they do next time.

January 20, 2022

The Southern Plantation – Part 1

I don’t consider myself particularly “woke” in the modern vernacular, but I did find myself uncomfortable admitting in my books that I drove a mule wagon on a southern “plantation”. The term seems widely accepted in the south, but my books are read in other parts of the world. That is why I self-consciously referred to my employer as a hunting “lodge”. In an era when the master bedroom is now called the primary or main bedroom, how is it that we have large tracts of southern property that we still call plantations?

To be fair, the plantation that employed me on Gillionville Road outside Albany, Georgia was established long after slavery was abolished. From the time it was purchased in the late 1800s until it ceased operation and was sold a few years ago, Gillionville Plantation had been devoted to hunting—especially bobwhite quail.

Plantation comes from the Latin word plantare, meaning “to plant”. Oxford Reference broadens it to “an estate on which crops such as coffee, sugar, and tobacco are grown, especially in former colonies and once worked by slaves”. A plantation, then, is actually just a place where crops are grown. But it is that last bit that makes it such a highly charged term.

So, I did a little research and have come to believe that perhaps I am being oversensitive. Modern plantations certainly weren’t built on the backs of slaves, and they aren’t preserved like monuments to Civil War generals. Many modern plantations are historic sites that educate visitors about the horrors of slavery. Others have been turned into wildlife habitat and forestry preserves, harkening back to their original meaning as estates on which crops are grown.

Plantations have been around since the ancient Romans developed large farms called latifundia, which used slave or paid labor to grow crops and livestock for sale. New world plantations began in the mid-1600s when slave traders brought workers for the sugar and coffee plantations of the West Indies. During the American colonial period, plantations existed as far north as the Hudson River valley of New York, but this type of agriculture eventually became synonymous with the South. During the early seventeenth century, English colonists in the southern part of North America began looking for ways to produce goods or raise crops that could be sold for a profit in England or Europe. Colonists experimented with raising mulberry trees to support silkworms for making silk. They also tried growing grapes for wine production and harvesting trees for timber. But it was the indigenous American tobacco plant that emerged as the crop that offered the greatest potential for profitability. Tobacco, however, required hundreds of acres of land, it quickly drained the soil of nutrients, and it needed a large labor force to tend the fields and to harvest and prepare the crop for market.

At first, colonists used indentured servants, who worked up to seven years without pay in exchange for their passage to the English colonies. But by the eighteenth century, owners of large plantations found it more profitable to purchase African slaves, who they could own and who would provide free labor for their lifetime. As Europeans began settling in the Carolinas and Georgia in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, they began experimenting with raising rice, indigo (used in making dye), and cotton for the market, all of which also required extensive acreage and free labor. Thus, the first two centuries of European settlement in the southern part of North American firmly established a new definition of a plantation: a very large farm that used slave labor to produce a commodity for export.

The plantation model was so widely accepted that early Presidents were slave-owning plantation owners. George Washington’s Mount Vernon and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello are the best-known examples. But consider Ambrose Madison, a planter and slaveholder in Virginia, who arrived in 1732 to a plantation he called, ironically for the slaves who built it, Mount Pleasant. One of Ambrose’s grandchildren, James, spent his early childhood at Mount Pleasant while construction began on a brick Georgian house that would later become the center of President James Madison’s Montpelier. And there was Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage Plantation near Nashville, Tennessee. It was a self-sustaining property that relied on slave labor to produce cotton. When he first bought The Hermitage in 1804, Jackson owned nine African American slaves. At the time of his death forty years later, about 150 slaves lived and worked on the property.

Plantations were common in all of the states of the upper south from Virginia to Louisiana and North Florida to Kentucky. Virginia’s Shirley Plantation is the oldest active plantation in Virginia and claims to be the oldest family-owned business in North America, with operations dating back to 1614. The Magnolia Plantation along the Ashley River in South Carolina was established in 1676 by Thomas Drayton and his wife Ann. The couple were the first in a line of Magnolia family ownership that has lasted for more than 300 years.

The oldest of Georgia’s tidewater estates, Wormsloe Plantation in Savanna, was developed by Noble Jones who came to Georgia with James Oglethorpe in 1733. In fact, many of Georgia’s earliest plantations began around Savanna in the 1700s. Mulberry Grove Plantation in Chatham County twelve miles north-west of Savannah, for example, was an active plantation from 1736 until the end of the civil war when the great plantation house was destroyed by General Sherman during his march to the sea. The significance of Mulberry Grove included support for Georgia’s silk industry with its large mulberry nursery. When the silk industry failed, it turned its low marsh acreage to rice and became one of the leading rice plantations along the Savannah River. And Mulberry Grove is also famous as the place where the cotton gin was developed by Eli Whitney in 1793.

Owing to the size of the State and its being the southernmost of the original colonies, Georgia has an impressive list of nearly three dozen early plantations that still exist. Many of them are operated as historic sites that include reenactors and historic tours. The Jarrell Plantation State Historic Site, for example, is a state park on a former cotton plantation in Juliette, Georgia. Located in the red clay hills of the Georgia piedmont north of Macon, the site stands as one of the best-preserved examples of a “middle class” Southern plantation.

According to the Library of Congress, the importation of captives for enslavement was provided for in the U.S. Constitution and continued to take place on a large scale even after it was made illegal in 1808. The slave system was one of the principal engines of the new nation’s financial independence, and it grew steadily until it was abolished by war. In 1790 there were fewer than 700,000 enslaved people in the United States. By 1830, there were more than two million and on the eve of the Civil War, nearly four million were enslaved—with nearly a half-million of them living in Georgia.

When slavery ended in 1865, another form of labor replaced it. Many freed African Americans had no choice but to return to the plantations to work as sharecroppers or as tenant farmers who rented land from white owners. Both tenant farmers and sharecroppers raised cotton, livestock, and other agricultural products that primarily benefitted the white plantation owners. But with the end of free slave labor, the old profitability model of the plantation became unsustainable. By the late 1800s, plantations were failing and falling into disrepair. That is when wealthy Northerners began buying up property at bargain-basement prices and resurrecting those plantations using a very different model.

Dozens of properties that call themselves plantations still dot the landscape in Southwest Georgia between Albany and Thomasville. Gillionville Plantation, where I drove the mule-wagon, is one of them. It may have once been a cotton plantation, but it has been transformed into acreage that is befitting the original meaning of the word plantation.

Gillionville Plantation

Gillionville PlantationThe story goes that Walter S. Gordon of Atlanta, the governor’s brother, bought the Gillionville property in 1880. Mr. Gordon’s daughter, Loulie Gordon Thomson passed it on to her sons who turned it into one of the original quail hunting plantations in southwest Georgia. By the time I climbed on the wagon in 2016, South Georgia had become world-famous as a quail hunting destination. Plantations were synonymous with quail hunting and were actively developing and preserving thousands of acres of the signature, natural ecosystem of the American Southeast—the longleaf pine savanna. But how these properties went from cotton fields to quail habitat is another story.

December 22, 2021

Beginning the slow process of saying farewell

Not many people get to retire twice, but I said goodbye to my mules, Mike and Ike, last weekend. My days on the wagon watching quail hunters stalk the South Georgia pine forest have come to an end as I prepare for big changes in the new year.

In fact, my changes begin with Christmas because for the first time in forty years, we won’t be loading the car with gifts and driving to Louisville, Kentucky. The years of celebrating the season in my wife’s childhood home on Tyler Lane ended when her father died earlier this year. Elmer Liebert was the last of our parents and the sale of his house means life-long traditions have passed. We will need to find new ways to Celebrate Christmas.

When you get to retirement age, big life-changes aren’t necessarily a good thing. Our elderly parents have passed away and suddenly my wife and I are the oldest generation in the family. Gone are the days of exciting promotions and pay-raises at work, sitting in bleachers at our children’s sporting events, or learning a new skill. A good day is when I can go for a walk and not need a handful of ibuprofen when I get home. A triumph is remembering why I walked into a room to get something. And sleeping through the night without having to get up two or three times to stumble to the bathroom is, well, unheard of.

So, when we bought a house in Atlanta, I began to feel like a kid again. We won’t move until Karen retires at the end of this school year, but the honey-do list for the new house is growing by the day. And with the excitement of the move comes the months of anticipation and the endless goodbyes. At some point, I will take my final walk around the neighborhood, say goodbye to my Sunday School class, and walk out of Calhoun State Prison with my Kairos ministry team for the last time. Karen is already facing her school year of “finals”—the final first day of school, the final book fair, and the final Christmas break.

There is plenty for us to miss about life in Albany. I’ll miss all of the retired Marines in their red pickup trucks with Semper Fi stickers. I will miss Pretoria Fields Brown Thrasher Ale, the Festival of Lights at Chehaw, the five-minute drives to Publix and Home Depot. But all of my life, I have made the most unlikely of moves. As a young zookeeper who grew up on the sandy beaches of Florida, I moved to Canada in the fall of 1973 to face my first Arctic winter at the Toronto Zoo. Karen and I moved from Louisville to Tampa to Sioux Falls to Toledo to Greenville, South Carolina before settling in Albany seventeen years ago. Now, in retirement, we are once again taking the unconventional route. We are not retiring to a cabin in the mountains or a beachside bungalow. We are relocating to the heart of one of the biggest cities in America.

Our new home in Atlanta is within walking distance of four microbreweries and a pub called the Stratford, which has trivia night on Wednesdays. We look forward to a neighborhood with sidewalks, a home with a basement, and an elementary school across the street. We’ll enjoy the Christmas lights at the Atlanta Botanical Garden, the Atlanta Opera’s performance of the Pirates of Penzance, and summer Braves games at Truist Park. And while my fellow Atlantans are stuck in traffic on their way to and from work, I’ll be perched at my new writing desk looking out on my new back yard where Karen will be constructing her new garden.

I will, of course need to find a new outlet for my writing. Albany Herald readers probably won’t want to hear about my new life in that big city to the North. And the big city newspapers won’t be interested in the musings of a small-town writer. Since I retired in 2016, I’ve written about sixty articles for the Albany Herald. I’ve covered mules and dogs, nature and COVID, Albany history, and my own personal life. Maybe there is another book in all of that.

One of the oddest experiences so far occurred on the day I resigned from driving the wagon. As I drove home from the plantation, I reflected on my experiences and the many people whose lives crossed mine. But the greatest sadness came from an unexpected source. I never said goodbye to the ones I came to admire most. I was in direct contact with them for countless hours over the last few years. I learned from them and came to love being around them. I’ll cherish the time I spent with my mules, Mike and Ike, as much as anything else in recent memory.

I can’t say their feelings toward me are mutual, but I do recall the time a couple of months ago when I was loading them into the horse trailer, and I slipped and fell down. As I lay flat on my back looking up at two, half-ton mules with hooves as big as dinner plates, I thought I might be a goner. They could have squashed me like a pumpkin. But they both stood unnaturally still. I grabbed a harness, pulled myself to my feet and stumbled outside to catch my breath. Working with those mules touched my spirit in ways I didn’t expect.

So, in spite of the adage, “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks”, this old dog is looking forward to a new year and some new adventures. Wednesday night trivia with a locally brewed craft beer on the table sounds kind of cool. I might even try to introduce one of our Albany traditions to those big city folks at the Stratford Pub. They might enjoy a Monday night of Beer and Hymns—“Hey, Hey”.

December 2, 2021

If I could talk to the animals…

I usually enjoy the animal sounds in my backyard, but this squirrel was getting on my last nerve. I was reading on my back porch enjoying a balmy, fall afternoon. He was sitting on top of the gate arbor twenty feet away squawking at me—or so it seemed.

He was making that peculiar squirrel sound, “chirl, chirl, chirl”, over and over and over.

I try to stay attuned to all of those chirps, twitters, and squawks when creatures talk to each other. It is as though they are speaking in a foreign language. I am sure they mean something. I just don’t understand what it is. Most of the sounds are pleasant and melodic. Some sounds—like that squirrel—can be annoying. But I recently heard an animal sound that was other-worldly.

If I had been walking in the woods in a dense fog, I would have thought this was the musical score of a sci-fi movie and a flying saucer had just landed. But this music was all too real. I was outdoors on an early June evening in Louisville Kentucky and the buzzing, musical sound was the height of the seventeen-year cicada emergence. The noise at times was deafening.

Every seventeen years, billions of cicadas from what is known as Brood X tunnel up from underground to spend their final days trying to attract a mate. The cicadas I was listening to began their lives in 2004, when newly hatched nymphs fell from the trees, burrowed into the dirt, and fed on sap from the rootlets of grasses and trees as they slowly matured. All of that preparation had been leading up to the moment when they surface in droves—up to 1.4 million cicadas per acre—to molt into their adult form, sing their deafening love song, and produce the next generation before dying just a few weeks later.

The sound of an individual cicada sounds like the rapid clicking of an old-fashioned telegraph machine. It is actually just the love song of males trying to attract a mate, but when they all sing together it is said to be the loudest animal sound on the planet.

At the other end of the spectrum is the animal song I heard on a cool overcast afternoon in July 1997. I had just boarded a small boat with a half-dozen other people for a whale-watching cruise. This was not one of those large-scale ocean cruises, because these whales were spending the summer in an estuary at the mouth of Northern Canada’s Churchill River. As our small boat motored away from the dock into Hudson Bay, I was skeptical about seeing whales. The water was calm, but the river was wide at this point and very murky. How we were to find whales, I had no idea, but as it turned out, we did not need to find them. They found us.

About twenty minutes into our cruise, they just appeared around the boat. There was no way to count them because they bobbed up to blow and breathe, then sank back down. I suppose there were ten or fifteen animals—many of them longer than our boat.

When the guide on our excursion lowered a microphone, called a hydrophone, into the water, we heard the high-pitched chirps, squeaks, and squeals of wild beluga whales coming from the small boom box at the back of the boat. It was the chatter of a whale family on an outing, talking to each other as they made their way up the river. They seemed unconcerned over our presence—innocent and vulnerable.

The beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas) is an Arctic and sub-Arctic cetacean. It has unique characteristics that are adapted to life in the Arctic. These include its all-white color and the absence of a dorsal fin, which allows belugas to swim under the ice. The beluga’s body size is between that of a dolphin and a true whale, with males growing up to eighteen feet long and weighing over three thousand pounds.

Belugas are gregarious and form groups of a dozen-or-so animals, although during the summer, they can gather in the hundreds or even thousands in estuaries and shallow coastal areas. Belugas depend heavily on underwater sound for orientation, feeding, and communication. They use echolocation for movement, to find breathing holes in the ice, and to hunt in dark or turbid waters. In addition to the clicks they use for navigation, these animals communicate using sounds of high-frequency whistles. Their calls can sound like bird songs, earning them the nickname “canaries of the sea.”

There is heavy debate as to whether cetacean vocalizations can constitute a language. A study conducted in 2015 determined that European beluga signals share physical features comparable to “vowels.” These sounds were found to be stable throughout time but varied among different geographical locations. Like most true languages, the further away the populations were from each other, the more varied the sounds were in relation to one another.

Hearing the belugas, cicadas, and squirrels reminded me of Carl Sagan’s 1985 science fiction novel, Contact. It deals with the exciting prospect of human contact with intelligent, extraterrestrial life. It is almost amusing to think about humans trying to communicate with an intelligent, extraterrestrial life-form when we can’t—or won’t—communicate with each other. We are divided by language, by politics, and by, well, bull-headed stubbornness.

We clearly have much to learn about communication. One way I have attempted to improve my own communication skill is to listen more closely to the chirps, caws, and melodies of the animals in my own backyard. But I still don’t know what that squirrel was worried about. I was just sitting there on my porch. Surely he wasn’t worried about me. Finally, I got up to see what the fuss was about. Maybe there was a cat lurking in the shrubbery below the porch. Or maybe a snake was slithering up the crepe myrtle in his direction. But on closer inspection, I still couldn’t see any threat. As I eased in his direction, he turned and scampered down the fence.

I’m not sure but I think he cast a look back at me with a sly smile on his thin, squirrelly lips. I wonder if he won a bet with his friends back up the tree. He got me up, out of my chair, and outside to investigate…nothing. I took a moment to “communicate” what I thought of him and went back in to continue my reading.

November 15, 2021

Mushrooms

I am one of a handful of people in my neighborhood who prefers to mow my own lawn. My mower is not a riding mower nor is it self-propelled. It doesn’t move unless I push it. That means I know every square foot of my yard intimately and I take pride in the smooth, manicured look of freshly cut grass. It also means I notice anything that mars that perfection—like those mushrooms that appear literally overnight. How is it possible for something to spring up that quickly?

According to the dictionary, mushrooms are any of the various fleshy fungi of the class Basidiomycetes characteristically having an umbrella-shaped cap borne on a stalk. The term mushroom typically refers to the edible varieties. The inedible (poisonous) fungi with an umbrella shape are called toadstools.

The umbrella-shaped mushrooms I am thinking about are in the agaric family (Agaricaceae). These are the ones that have thin, bladelike gills on the undersurface of the cap that shed spores. They have a cap (pileus) and a stalk (stipe) and emerge from an extensive underground network of threadlike strands called mycelium. That is, apparently, where the magic happens.

The mycelium starts from a spore falling in a favorable spot and producing strands (hyphae) that grow out in all directions, eventually forming a circular mat of underground hyphal threads. Fruiting bodies of some mushrooms occur in arcs or rings called fairy rings that may widen year after year. As long as nourishment is available and temperature and moisture are suitable, a mycelium network can produce a new crop of mushrooms every year during its fruiting season.

The most common varieties of mushroom are probably the ones we find in the grocery store—especially the white or button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus). I purchased an eight-ounce package last week for my slow-cooker beef stew. They were in the produce section next to a variety of other edible mushrooms. After a little research, I discovered that those cremini mushrooms and portobello mushrooms on the next shelf are the same species as the button mushrooms, but at different stages of development. One reference says that if the button mushrooms are at the toddler stage, then creminis are the teenagers and portobellos are adults.

But what about all of the varieties I see around the neighborhood, `especially the ones that spring up in my freshly mowed lawn? Well, there are really too many to count and many of them aren’t actually mushrooms. They are probably fungi—and they have some pretty colorful names.

Among these are hedgehog mushrooms, which have teeth, spines, or warts on the undersurface of the cap, and club fungi with their shrublike, clublike, or coral-like growth habits. One club fungus, the cauliflower fungus, has flattened clustered branches that lie close together, giving the appearance of the vegetable cauliflower.

The morels are among the most desired wild mushrooms in the world. They are praised for their flavor, texture, and unique appearance, and are popularly included with the true mushrooms because of their shape and fleshy structure. They resemble a deeply folded or pitted conelike sponge at the top of a hollow stem.

The state of Georgia hosts some colorfully descriptive fungi that may be some of the varieties I see around my neighborhood. Wood ear mushrooms, a type of jelly fungus, have earlike shapes and prefer decayed logs and moist areas. Lacquered-shelf fungi grow on decaying hardwood trunks and brown rot fungi consume cellulose in rotting wood. Parasitic shoestring mushrooms grow on hardwoods and conifers and form dark shoestring-like strands under tree bark. One show-stopping fungus is a slime mold called “dog vomit” because of its vibrant yellow-orange hue and its creeping growth.

Georgia has some edible varieties of mushroom, like the chanterelles, but the only mushrooms I eat are the ones from the grocery store. I don’t want to take a chance on picking the wrong thing in the wild, like the one called the sickener mushroom. It has a brilliant red cap and thick white stalk with many white, close gills and, as the name implies, it can make you sick. And how about one called the death angel mushroom. This one displays a striking white cap and stalk with pure white gills underneath the cap and when eaten can lead to—well, death.

The only wild mushroom I have ever knowingly eaten were the ones my dad grew. They were shitake mushrooms that sprouted from four-foot-long, maple logs leaning up in the shade at the back of his cabin in the North Carolina mountains.

The Shitake (Lentinula edoides) is a common edible variety of mushroom that is related to the button mushroom but in a different family. Shitakes are native to Southeast Asia and have been harvested for centuries in the warm, moist hardwood forests of China and Japan. They sprout from the decaying wood of deciduous trees like chestnut, oak, and sweetgum and are available in my grocery store.

My dad’s spores arrived by mail in a small plastic bag. They were a pressed sawdust product that had been infused with spores and molded into one-inch-long plugs that fit neatly into a quarter-inch, round hole. My brothers and I were charged with drilling hundreds of holes into a pile of four-foot-long, hardwood logs. After we had hammered the spore-plugs into the holes, we took the logs to the back of the cabin where dad dropped them into an old bathtub filled with water. He weighted them with some cement blocks to soak for a day or two then stood them up against the back of the cabin in the moist shade to germinate. I don’t remember how long it was before he had mushrooms, but the end product was both dramatic and delicious. He freeze dried his harvest and kept the mushrooms in shrink-wrapped bags. The only visual evidence I have of dad’s mushroom production is a woodcarving I gave him for Christmas in 1995.

I have a special fondness for mushrooms. They are elegant and beautiful, but they can also look like dog vomit. They are delicious, but they might kill you. As the saying goes, all mushrooms are edible, but some of them only once.